Images of the Other World. Chronicles of Exiles in America †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Things of the Other World

Everybody’s Drama

3. Public Space and Private Vision

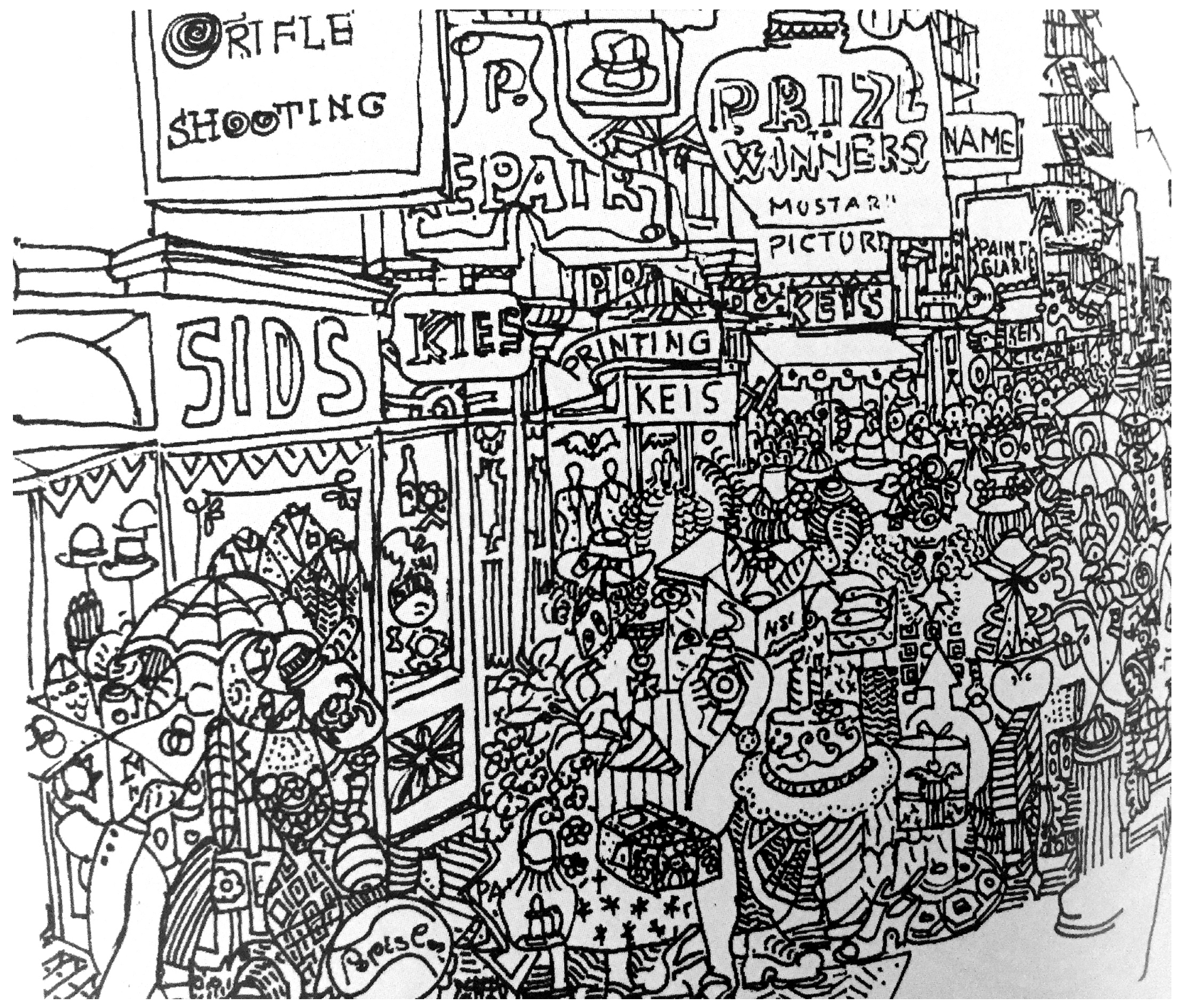

3.1. The Crowded City

3.2. Postcards

3.3. The Unbelivable City

3.4. On the Road

4. In Itinere

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costantino Nivola (1911–1988), for His Biography. Available online: http://www.museonivola.it/costantino-nivola/biografia/ (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Xanti Schawinsky (1904–1979), for His Biography cf. Xanti Schawinsky; Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst & JPR|Ringier: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015; p. 156. Exhibition Catalog Curated by R. Gygax, 21 Febbraio-17 Maggio, 2015, pp. 167–169; cfr. anche. Available online: http://www.schawinsky.com/bio (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Ward, S.V. Selling Places; Spon Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino, C.C. Silenzio, Loquacità e balbuzie. In Puzzling. La Costruzione Dell’opera tra Progetto e Sospensione; Curated by Fiorentino, C.C.; La Scuola di Pitagora Editrice: Napoli, Italy, 2012; pp. 40–84. [Google Scholar]

- Grosz, G. Un Piccolo si e un Grande No; Grande Libraria Longanesi & C.: Milano, Italy, 1975 (first Italian edition 1948); first edition: A Little Yes and a Big No; Dial Press: New York, NY, USA, 1946.

- Una Campagna Pubblicitaria. Avanguardia Nella Tecnica, by Leonardo Sinisgalli and Ufficio Tecnico di pubblicità Olivetti, Milano, Stampa S.A. Alfieri & Lacroix, 1939; document of the Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti di Ivrea_AASO; text by Elio Vittorini, images by Costantino Nivola and Giovanni Pintori. Cf. Fiorentino, C.C. Una campagna pubblicitaria, in Fiorentino, C.C. Millesimo di millimetro. I segni del codice visivo Olivetti 1908–1978, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2014, pp. 67–87.

- Olivetti Studio 42, Typewriter. Design by Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini, Ottavio Luzzati and Xanti Schawinsky and for its debut communication: Costantino Nivola, Giovanni Pintori, and Elio Vittorini with Leonardo Sinisgalli.

- This also refers to la storia dei vinti (the history made by won people), according to the texts of Simone Weil, Walter Benjamin and Franco Fortini. A theme shared by Vittorini who wanted to draw up a publication consisting of biographical interviews. Cf. Vittorini, E. Lettera al Padre, 22 December 1845. In “Il Politecnico” di Vittorini; Borrelli, M., Ed.; Oblique Studio: Rome, Italy, 2011.

- Americana is an anthology that contains texts selected by Elio Vittorini, among the works of 33 American authors including: Irving, W.; Poe, E.A.; Melville, H.; Twain, M.; O‘Neil, E.; Fitzgerald, F.S.; Boyle, K.; Faulkner, W.; James, H.; Hemingway, E.; Mr. Stein. Translators of the Americana team were: Vittorini; Pavese, C.; Piovene, G.; Morra, U.; Moravia, A.; Montale, E.; Linati, C.; Conti, P.G.; Fulchignomi, E.; Mr. Ferrata. Concerning Americana, cf. Marchianò, A. Americana di Vittorini tra Audace Sconfinamento Letterario e Proibito Percorso Editoriale. in Acts of the convention: La letteratura degli italiani rotte confini passaggi; XIV Congresso Nazionale della Associazione degli Italianisti, (Genova, 15–18 September 2010), papers published by DIRAS, University of Genoa, 2012. ISBN 978-88-906601-1-5. See also Manacorda, G. Come fu pubblicata “Americana”. In Elio Vittorini, Proceedings of the Acts of the National Conference of Studies, Siracusa-Noto, Italy, 12–13 February 1976; Sipala, P.M., Ed.; Ermanno Scuderi; Greco: Catania, Italy, 1978; pp. 63–68.

- Saroyan, W. Myself upon the Earth, the Daring Young Flyng Man on the Trapeze and Other Stories; The Modern Library Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1941; pp. 51–66. Prima ed. 1934. Cf. Fiorentino, C.C. Me Stesso Sulla Terra. In Congegni Sapienti. Stile Olivetti il Pensiero Che Realizza; Fiorentino, C.C., Ed.; Hapax editore: Torino, Italy, 2016; pp. 143–156.

- Vittorini, E. Le città del mondo. Il Politecnico, 1946, n. 30.

- Vittorini, E. Conversazione in Sicilia, Bompiani, Milano, 1941. This novel, for the first time, was published in batches in the journal “Letteratura”, 1938–1939. The first editions in a single volume appeared with the title Nome e lagrime, Parenti, Firenze, 1941. In the 1953 was made the edition illustrated by Bompiani, with photographs by Luigi Crocenzi. Renato Guttuso’s drawings, made in the Forties, were only published in 1986 for the Rizzoli edition. The Olivetti edition is was made in the 1973, it was strenna, with the photographic boards by Enzo Ragazzini.

- Pavese, C. Ieri e Oggi. L’Unità, 3 August 1947. Reprinted in: Pavese, C. La Letteratura Americana e Altri Saggi; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1959; pp. 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- For the Biography of Saul Steinberg. Available online: http://saulsteinbergfoundation.org/chronology/ (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Ruth Guggenheim Nivola (1917–2008) helped Nivola, Giovanni Pintori and Salvatore Fancello to Work at the Olivetti in 1936, after studying at the ISIA of Monza where they had met.

- Altea, G. Questioni di identità. In Nivola. La Sintesi Delle Arti; Altea, G., Camarda, A., Eds.; Ilisso edizioni: Nuoro, Italy, 2015; p. 127, notes numbers 168 and 169. [Google Scholar]

- Altea, G. Questioni di identità, in Altea, G., Camarda, A., op. cit., 2015, p. 121Cape Cod, the Massachusetts peninsula rolling on the waters of the Atlantic Ocean is a place of voluntary exile and freedom; in addition to the events surrounding the lives of those who have chosen it as a place of choice, various literary texts have contributed to the construction of an imaginary linked to this place which, to this day, is part of a myth; just as it does for other places where men and women have gone for the sake of space for freedom and action and who have attracted, at certain historical periods, groups of people who, even in a different perspective, have found the impetus for their poetic personalities. From Altea, G. Questioni di identità, in Altea, G., Camarda, A., op. cit., 2015, p. 100: “una località che era meta estiva di diversi ex-maestri e allievi della Bauhaus. Vi trascorrevano le vacanze Walter e Ise Gropius, Breuer, Herbet Bayer, Moholy-Nagy e Xanti Schawinsky e, accano a loro, altri esponenti della cultura americana e dell’emigrazione intellettuale europea cui Nivola era legato o con i quali avrebbe rapidamente stretto amicizia: Nicola e Miriam Chiaromonte, il giornalista Dwight McDonald, la scrittrice Mary McCarthy, l’architetto inglese Serge Chermayeff, l’artista Ungherese Györg Kepes, l’architetto austriaco Bernard Rudofsky, Steinberg e la moglie, la pittrice Hedda Sterne, una cerchia in parte coincidente con quella che si riuniva ogni mercoledì al ristorante Del Pezzo, nella 47esima, in occasione dei pranzi presieduti da Nivola, animati appuntamenti in cui si Incrociavano diversi ambienti della cultura newyorkese”.

- Nivola, C. La Città Gremita. Domus, May 1947, p. 219. Cf. Altea, G. Questioni di Identità; Altea, G., Camarda, A., Eds.; Ilisso edizioni: Nuoro, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Altea, G. Questioni di Identità; Altea, G., Camarda, A., Eds.; Ilisso edizioni: Nuoro, Italy, 2015; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, N. Postcards: Cartolina da Roma, Cartolina da Milano, Cartolina da New York, Cartolina Dall’America, pen and pastel on paper, cm. 76.2 × 56, 1978, private collection, printed in Licht, F., La pittura, in Ugo Collu, Alberto Crespi, Fred Licht e Salvatore Naitza, Nivola. Dipinti e Grafica, Jaca Book, Milano, 1995, figg. 45–48.

- Licht, F. La pittura; in Ugo Collu, Alberto Crespi, Fred Licht e Salvatore Naitza, Nivola. Dipinti e Grafica, Jaca Book, Milano, 1995; pp. 74–75.

- Miller, H. The Air-Conditioned Nightmare; New Directions: New York, NY, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- In a version of the painting Times Square, 1946, Nivola inserts the components of his family: Himself, Ruth and his son. See Altea, G. Questioni di Identità; Altea, G., Camarda, A., Eds.; Ilisso edizioni: Nuoro, Italy, 2015; pp. 80–82.

- Ibidem. p. 100.

- Gygax, R. Forward and Backward. Process-Based Painting. In Xanti Schawinsky; Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst & JPR|Ringier: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015; p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Xanti Schawinsky. Transition, 1960. Oil on Canvas, cm. 203.4 × 381.4 × 5.3. © Xanti Schawinsky Estate Zürich. Another Work Done with the Same Technique is: X. Schawinsky, Come closer, 1960; cf. Available online: http://www.migrosmuseum.ch (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Ibidem.

- Xanti Schawinsky. Bond Clothes (Broadway), 1951. Photography in B/W, cm. 20.3 × 25.3, © Xanti Schawinsky Estate Zürich. Cfr. Available online: http://www.migrosmuseum.ch (accessed on 10 September 2017)e Cf. Xanti Schawinsky; Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst & JPR|Ringier: Zurich, Switzerland 2015; p. 156; catalog of the exhibition curated by Gygax, R., 21 February–17 May 2015.

- Cf. Fagone, V. Nota Introduttiva All’opera Fotografica di Xanti Schawinsky. In Xanti Schawinsky. Foto; Neumann, E., Ed.; Edizioni Benteli Verlag: Berna, Switzerland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gygax, R. Forward and Backward. Process-Based Painting. In Xanti Schawinsky; Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst & JPR|Ringier: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- In 1951, Costantino Nivola and Bernard Rudofsky designed and built the Nivola’s garden in Long Island. In this regard it’s worth to mention even the relationship between Nivola and Pietro Porcinai, designer of the green areas of the Olivetti factory in Pozzuoli. Cfr. Mereu, A., Il Nivola Ritrovato. Un’artista tra l’America e il Mugello, Nardini Editore: Firenze, Italy, 2012.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fiorentino, C.C. Images of the Other World. Chronicles of Exiles in America. Proceedings 2017, 1, 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090886

Fiorentino CC. Images of the Other World. Chronicles of Exiles in America. Proceedings. 2017; 1(9):886. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090886

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiorentino, Caterina Cristina. 2017. "Images of the Other World. Chronicles of Exiles in America" Proceedings 1, no. 9: 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090886

APA StyleFiorentino, C. C. (2017). Images of the Other World. Chronicles of Exiles in America. Proceedings, 1(9), 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090886