Abstract

Results from the study ‘nature’s significance for human well-being’, shows that “The Rug of Life” gives additional value to the narratives. The method is qualitative with in-depth interviews combined with visual methodology of sixteen respondents between ages 25–76, who are living close to nature. In the interview it was asked what kind of nature has a meaning for them and how they estimate their well-being and nature’s impact on it and how quality of life are experienced, as well as nature’s and the local rural environment’s significance as a health promoting factor. The study has a salutogenic approach.

1. Introduction

This paper is a part of a study with the aim ‘nature’s significance for human well-being’. The part that is given more attention in this paper is “The Rug of Life” as a complementary tool to narratives, as representation, an interaction between interviewer and the interviewed, a new projective, creative and innovative therapeutic tool to understand human thinking and behavior.

To promote health is more than healthcare [1]. Focus on the salutary and with the person as a whole is appropriate for health promotion programs, in all fields. When people are able to plan their own lives and when they find the meaning of life, as well as find rewards and challenge on a deeper level, health and wellbeing is enhanced. With focus on resources, strengths and possibilities as well as competence, ability, and assets on different levels and in different roles; individuals, as members of groups and families as well as in society, is also favorable for health. In a lifelong perspective, all the different systems in the actual environment create a unique human being. This is the core of Aaron Antonovsky´s salutogenic model, with the components comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness that contributes to a Sense of Coherence [2]. Salutogenesis means the origin of health and the salutogenic model is a health promotion theory, where the entire person is in focus with emphasis on salutary, not only the disease.

The Sense of Coherence (SOC) concept, include three components: comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness [2]. High scores on these components conduce to a high SOC. Comprehensibility is an understanding to and a capacity to assess reality. A person with a strong comprehensibility believes that experiences are structured, ordered and possible to explain, rather than chaotic or randomized. The manageability component in SOC is an awareness of the resources you have, and an awareness when which resource is needed when. With a strong manageability the person does not feel unfair treated by life and have confidence in his or her own resources, and that they are available to meet life´s demands. Meaningfulness is according to Antonovsky the most significant component in SOC and represents motivation, complicity and participation in different contexts [2]. With a strong feeling of meaningfulness, a person takes demands as challenges and find meaning in things that facilitate the individual´s ability to be effective.

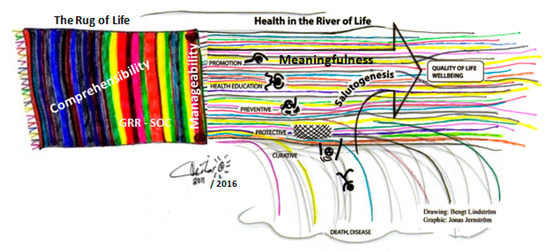

Antonovsky used a river as a metaphor of life [2]. Both are full with risks and resources. He called this river”. The River of Health”. When you move from the waterfall, where the cure or treatment of the disease are located and goes upstream, you find prevention of diseases, and then health education and on the top health promotion. With this “River of Health” it’s easier to understand the meaning of action in different stages of health achievements and when they take places. In the salutogenic model, focus is on the movement to health, and then good health is a determinant for quality of life. Eriksson and Lindström have developed Antonovsky´s”. River of Health” to “Health in the River of Life” [3]. When we are born, we fall down in the river and will flow downriver, and as the years go by we learn to swim. Some children are born on the pool water and have time to learn to swim. Other children are born close to the waterfall where they have to struggle to survive. Our results where ever we end up in the river is based on our orientation and learning through our life experiences and what we have acquired through them. The health process is a learning process where we reflect on what creates health, what kind of alternatives we have for life and what improves quality of life.

Human life can also be explained as a rug. When we are born, we start to weave our rug and do it until we die. How we weave the rug and with which colors are unique for every individual. You can order the rug warp when threads cross each other and understand way they do so, so that you can continue weave the rug. In other words, “live your life”. You are aware that sometimes a thread in the rug warp can break. To carry on weaving you have to unravel the threads or to wrap up those thread that are broken. The color in the rug can perhaps be a little darker at this time. Finally, you look forward to the rug design. The color can vary after fancy and mood over time. Threads breaking are normal, but you can wrap them together again and you are satisfied with the rug design until this moment.

“The Rug of Life” is possible to combine with “Health in the River of Life”. By combining “The Rug of Life” with “Health in the River of Life” you get another comprehensive view over a person’s resources (Figure 1). We are in the present (manageability) together with all stressors in our surrounding as well as our resources and experience in our baggage (comprehensibility). Depending on the tensions that are present and the environment where we are as well as how we feel, we end up in different places in the river (meaningfulness). Do we swim across the river, or do we need to improve our swim technique? Is it a day when we need a lifebuoy to across? Are we alone and without support? The colors and pattern in the rug are comprehensible and can be explained. You are aware of your resources and they are available as well as manageable. In addition, it feels meaningful to swim across the river.

Figure 1.

“The Rug of Life” combined with “Health in the River of Life”.

The GRR-part (Generalized Resistance Resources) concept, of the rug as well as the SOC-part is the part of the rug that is weaved. Our everyday life is full of stressors that we are exposed to and that leads to a state of tensions. Different kinds of stressors, for example chronic stressors, are a life situation or a state in a person’s life. It can be your own social roll, belonging to a group, culture and so on. These stressors are generalized and long-lasting in a person’s life. Different life events are also a kind of a stressor. For example death, divorce, new workplace, a new family member, retirement and so on. These states we handle with resources that we have been collecting.

These resources are the GRR-part of the rug and makes stressors in our surrounding comprehensible. In a way, they give us continuous experiences that strengthen our SOC. This GRR is bound to individuality as well as to the nearby environment where the person lives and also to the distant environment [2]. It can be resources such as money, home, self-esteem, knowledge, heritage, healthy orientation, and contact with inner feelings, social relations and existential questions such as faith, religion and meaning of life. These are GRR factors, which develop SOC. The SOC-part in the rug gives us experiences that can contribute to a stronger sense of coherence.

“The Rug of Life” is a new tentative method that makes humans resources and Sense of Coherence visible, as well as has a theoretical anchoring to and a further development of Aaron Antonovsky´s salutogenic model [2]. Thoughts change forms with words as well as with visual methods. When formulating thoughts into words and drawings, words and drawing may coincide or vary. Thought may take another expression with a visual method. As an example: when we think, our thought looks like a pear. When we put words on our thought, it turns out to be an apple. When coloring our thought in a rug, our thought may look like an orange or turn out in to a banana or a bunch of grapes. Results from the present study partly validate this hypothesis, but need additional research to be validated.

Nilsson, Sangster and Konijnendijk advocate the study of environmental health consequences and the quality of related therapy through a multi-method, multidisciplinary, approach [4]. In the present study, the research method is multidisciplinary with behavioral science as the base and with focus on human’s behavior. The interaction between human and the environment, in this study nature, belong to environmental psychology. In addition, countryside as a living environment is studied in rural sociology, while health and welfare belongs to the discipline social policy. The Human-Nature salutogenic relationship ought to be seen with a wide-angle perspective i.e., from different sciences to get a comprehensive view.

The Relationship Human and Nature

Health and well-being have been connected to nature for a long time, through nature walks, outdoor life and gardening. In the 5000-year-old Gilgamesh-epos from the Orient, greenery where connected to well-being [5]. Also in Garden of Eden and in Elysion, beautiful nature where connected to well-being. In 1853, Thoreau wrote that every minute in nature is good for people and in the late 19th century, Muir argued that wilderness is the cure for stressed people. Gardening is also significant in the healing process, as Hirschfeld stated at the end of the 18th century and suggested that hospitals should be surrounded by gardens.

Sensory gardens where historically designed to inspire and to strengthen our five senses sight, smell, hearing, touch and taste, with healthy herbs, fresh air and a view that heals our brain, body and soul [6]. They contributed as well with a therapeutic action for those who needed it. The same potential exists today. As Albert Einstein’s word: When you sit in a nice garden for two hours, it seems like two minutes; when you sit on a hot stove for two minutes, it seems like two hours. That´s relativity [6] (p. 34). Those who designed sensory gardens were aware of nature’s healing capacity, the need of local food, as well as that gardens should provide people with outdoor activities for all ages [6]. Sensory, healing and therapeutic gardens can engage and encourage humans with different backgrounds and ages, as well as gives the opportunity to reunite both socially and with nature. Nature as health promoter is also valid today, according to Kaplan and Kaplan and Ulrich [7,8], and a number of studies around the world. According to Souter-Brown, the time is now right to reunite nature´s historical role in human´s everyday life [6].

The supposedly hereditary quality that makes human enjoy being in nature and with other forms of life together with sources of water, food and safety, and possibility to relax, contributes to human survival. This quality is called the biophilia hypothesis [9]. Being in natural environments promotes faster and a more complete recovery from negative stress [7]. Nature environments such as savannah-like open landscapes, for example thin forest and view over water, are environments that charges human “batteries” and are mentally restorative [10]. A restorative experience of nature, that reduces mental fatigue, plays an important part for recovery [11,12]. According to Beddington et al. children develop in early age their resilient capacity towards stress and general psychological disorder [13]. Later in life, this resilience capacity can create well-being until old age. In addition, Molcar´s research shows that a considerable part in human´s well-being is to have a secure home to witch to feel attached and to have an affinity [14]. Our environment is crucial to develop this resilient capacity [15]. Both built and natural surroundings may promote social interactions, group contexts and mental health. It can be considered that the respondents in the present study find their restorative recourses in nature.

2. Materials and Methods

A qualitative research method combined with visual methodology is used in present study. Using an integrated method that involves both visual and word based research method, provides a way to study both diversity and complexity [16]. With a qualitative method, you get a deeper understanding in human’s subjective experiences and of the quality of life among other things [17]. You can also find the exceptional, unique in human’s relation to nature [18]. The qualitative method gives information about social process, perception and approaches. The visual method with drawings is a rich and perceptive research method to study how humans understand their world [16].

According to Guillemin there is a comprehension that drawings are appropriate and suitable for those that not in fully are able to articulate their thoughts and feelings through words or to write [16]. It is also unlikely that you draw the same pattern after a year, a month or a week. This signifies that drawings can show the illustrator’s history, present and even their future [16]. The illustrator can understand his or her state at the place and time when he or she is doing the drawing and with the help of the drawing, you can understand how the illustrator looks at his or her world.

In the present study, narratives where collected until the information where theoretical saturated and did not give any new knowledge with theoretical sensitivity [19]. Selection of respondents where with theoretical sampling obtained through announcements in periodicals [19], those who wanted to state what meaning nature has for their quality of life and well-being from a salutogenic approach [2]. This method can be referred to grounded theory [19], which is a method where you frame new theories about human behavior through qualitative data [17]. Grounded theory is a research approach with a systematic and flexible way to collect data and to analyze social processes and activities [20]. This is used with intention to develop a theoretical model to understand and explain what is studied. In this case, the study concerns human relationship with nature and nature’s significance for human well-being. A central part of analysis is that the research problem emerging from the collected data and the core variable is found of how the respondents cope and handles the main concern [19].

After the in-depth interview, the respondents colored a “rug”. They were given a white paper with a framework of a rug and pencils with 12 different colors. While they colored the rug, as well as after finishing it, they explained what has happened in each phase of life and why they choose specific colors. Drawings give most when they are combined with interviews, when drawings are as a continuation on the narrative [16]. Both the drawing and the illustrator’s interpretation of her or his drawing, is analyzed. This gives a suitable way to express themselves especially for those that are more visual than word oriented.

By analyzing life stories you can consider humans life as they remember it themselves, to develop an understanding for the question at hand [21], as in the present study, to understand the individual relationship to nature under the whole lifespan. With Aaron Antonovsky´s salutogenic model that focus on salutary [2], with the components comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness that contributes to a Sense of Coherence as a point of departure, the respondent’s main concern (core variable) were determined [19]. These are summarized into two ensembles, theoretical models and “The Rug of Life” is with the help of respondents verbal stories analyzed as a projective tool showing how respondents cope with life challenges.

3. Results

Results in the present study shows that the main concern (core variable) among the respondents is a need of the countryside, with a nearby nature that promotes health. There are two different ensembles of need developed from categories found in the data, that forms two theoretical models [19], where one is called “Back to nature” and the other “Roots in soil”.

Respondents in “Back to nature” have moved from an environment they experienced as stressful to an environment they experiences as calmer, from an urban area to a rural area. These respondents have mention during the interview different life crisis. Those respondents that have constantly had nature in their daily life and something that they do not want to abandon, form the “Roots in soil” group. This group has had life crises but only a few mention them during the interview. Various studies shows that those who are in a life crisis have difficulties to manage their surrounding [22]. Those who have difficulties to manage their surrounding have a need of a so-called biophilia environment. Referring to Ottosson et al.´s study [22], the author concludes that respondents in “Back to nature” have had a need of a supporting environment, a biophilia environment and thus moved to a rural area.

A summary of the main categories found in the data, the ensemble “Back to nature” have a need to downshift that appears when they notice that they have only achieved, and that is not what they want to do. They emphasized freedom as important, to take care of oneself. As well as see richness in the seasons with spring, summer, autumn and winter. The seasons make them feel more present in life. Therefore, they have started to think “What do I want to do with my own life”. While the main categories in the ensemble “Roots in soil” are factors as to be alone, self-elected aloneness stakes a major part of respondent’s life and seems to be a very important part. They also feel that it is a richness to live where they have grown up, as well as to have time to do things they like.

One of the categories that the two ensembles “Back to nature” and “Roots in soil” have in common is that they have nature through “mother’s milk”. As child, they have spent time in any kind of nature and then in elderly days they use nature in some form of recreation to charge their batteries. Life is perceived more meaningful and for example money have a minor role. In addition, a factor they have in common is to have space to move freely which scored high. There is a perceived feeling among the two ensembles to be able to live a simpler life and to have an opportunity to more self-sufficiency. To live in rural areas seems to perceive to give quality of life.

When analyzing “Back to nature” and “Roots in soil” with Antonovskys´s salutogenic model and with the Sense of Coherence (SOC) concept, Generalized Resistance Resources (GRR) can be found [2]. In the present study, you find a Sense of Coherence and an ambition to feel good as well as how to handle stressors that our surrounding is full off. The narratives can be related to the GRR recourses as well as to SOC components comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness. “Roots in soil” have more comprehensibility and meaningfulness than “Back to nature”. Manageability is significant in both ensembles.

Concerning restorative places in nature that can be linked to a sense of coherence, according to the respondents in “Back to nature” and “Roots in soil”, is places with water, forest and on the peat. These places give them energy and are a place where they feel good. Those that did not mention life crises have water as their charging depot. Although every form of green area improves self-esteem and mood [23], a presence of water generates a considerable effect. In Korpela and Hartig´s study the favorite places score high [24], on the Perceived Restorativeness Scale they use. Also in present study there are restorative aspect regarding favorite places, which shows through respondents´ evaluation of their favorite places. Favorite places can be used in intention to regulate unpleasant feelings according to Korpela [25]. For example low self-esteem. Favorite places can also be used for more pleasant feelings, that place context conduce with.

Decoding “The Rug of Life´s” Additional Value to the Narratives

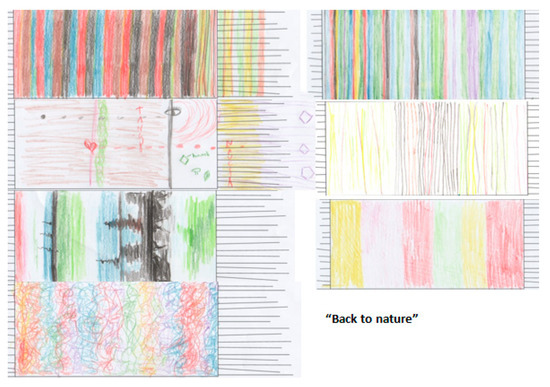

After the main interview, respondents were asked to color a rug in a form of a timeline. Respondents in “Back to nature” consists of four women and three men and their average age are 50.1 year. They have been having a need to change environment to a calmer choice and a life with nature. Their rugs (Figure 2) suggest a need of calm [26]. They are chaotic and colorful with the red color dominating. Red and warm colors mean clarity, noisiness and stimulate feelings [27]. All the seven rugs together gives a warm, dark and bizarre expression which can be decoded as exciting, relaxing and equating a person’s own chaos. A synecdochal view is that the rugs embrace average of SOC [26]. The manageability component in SOC is here and now, and the last color in the rug is dominated of the red color that can be decoded as clarity when the rugs where colored.

Figure 2.

The seven rugs that forms the group “Back to nature”.

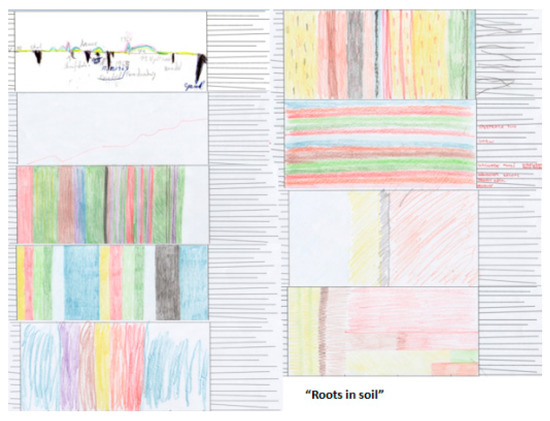

”Roots in soil” have an average age of 46.3 years and five of them are women and four men. They appreciate to be close to nature where they are able to be alone as well as have time to do things they values. Their rugs (Figure 3) show a calm state of mind and give a light and harmonic expression dominated of blue and yellow colors [26]. Blue and cold colors are decoding as dimness, quietness and a sedation of feelings and yellow means neutrality [27]. The rugs gives also a cold, clear and perfect expression that can be decoded as calm, stimulating and where anxiety and apprehension can be worse. As things stand in “Roots in soil” with the component manageability, here and now, the blue color is dominated and that can be decoded as restful and peaceful.

Figure 3.

The nine rugs that forms the group “Roots in soil”.

The rugs in “Back to nature” amplify the need to downshift, a need to look for a calmer environment. They have an awareness of their resources and confidence to make a change. The black, bizarre and emphatic expression in the rugs with a pattern that mirror a person’s own chaos, signify a need of a calmer environment but with a clarity when the rugs where colored. The rugs in “Roots in soil”, those that have been living most of their time in rural areas close to nature, gives a calm, harmonic and stimulated impression, with the light colors dominant. This amplifies their appreciation to be close to nature and to have an opportunity to be alone as well as have enough time, as the time the interview where made was restful and peaceful. Respondents in “Roots in soil” have an understanding to and a capacity to assess reality and find meaning in their relation to nature, as well as confidence in their own resources.

4. Discussion

The rugs in the two ensembles together with the narratives tells that at a time in life, after an eventful life that have resulted in that you don’t feel well, you can make a new turn and choose to do something else. The conclusion of the rug as a method is that the rug may give an amplified value of the narratives. The told story in relations to the rug gives it an anchoring [26]. The rug is complex, polysemic, while there is different kind of patterns and tone of color, which can be divided in clusters. Signs cover that every rug is unique. However, as a group the rugs develop clusters that can amplify the two theoretical models “Back to nature” and “Roots in soil”. The metaphor of the rug is that it makes the life story visible in another way, as the example with the thoughts and fruits. This hypothesis “thoughts and fruits”, as mentioned, need additional research to be validated.

A picture makes things visual in another way than words. It can give birth to a thought and a reflection to take a new direction. You can get an understanding and an awareness that can make another type of satisfaction. As child, we use our fantasy more. Children plays, draws and paint in another way than adults. To maintain this ability throughout life, can contribute to an improved sense of coherence as well as “The Rug of Life” can contribute with an awareness of your own resources and assets. Comprehensibility is the ability to understand experiences. The chaos in the rugs shows awareness about your past that you can talk about, or draw. Manageability is that you have self-confidence in your own capacity to manage things. With the chaos in the rugs, the experience you are aware of, you can tackle current challenge that gives meaningfulness. A belief in the capacity that you can use it to construct meaning and perceive purpose in life, as to swim across the river. Respondents in the present study have spent their childhood in any kind of nature. Nature is something that has been following some of them all life, “Roots in soil”, as a place of recreation. In addition, some of the respondents have embraced nature to heal themselves when they have gone to the bottom, “Back to nature”. At the time that the respondents drew their rug, I sensed that the respondents were pleased with their life, as the last color in the rug also amplifies. Some of the respondents have a more chequered life than others, but in common, they have used nature as a restorative place. Nature is an element they have learned to know as child, a place where they have been feeling safe. To integrate childhood with nature gives them a resource to use when energy runs out or as a promotion factor so that energy never runs outs absolutely.

5. Conclusions

The present study show that “The Rug of Life” can be a complementary tool to narratives (in-depth interviews), as a new projective, creative and innovative therapeutic tool to get another understanding of humans thinking, thoughts and behavior. It is a method that may reflect how humans cope with demands of life. “The Rug of Life” can be used in individual discussions as well as in group coaching where focus is on individual resources, or in a therapeutic term with children, adolescents, adults or with couples. “The Rug of Life” is both a product and a process, and it is a multifaceted, creative tool to express resources as well as may have a clear connection to your own life.

There are a number of researches investigating nature as a health promoting factor, but the present study’s contribution is the focus on health factors, salutary factors, that promotes health as well as the qualitative method combined with visual method, which may give a clearer picture of respondents reasoning. Another contribution that this study gives is the development of a complementary tool to narratives, “The Rug of Life”, as a tool to use in health promoting research. However, this “The Rug of Life” method needs additional research.

Acknowledgments

Ellen, Hjalmar and Saga Waselius scholarship, as well as Alli Paasikivi foundation, Nordenskiöld-fellowship and Swedish-Ostrobothnia fellowship fund the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Available online: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/ (accessed on 22 May 2017).

- Antonovsky, A. Hälsans Mysterium (Unraveling the Mystery of Health); Natur och Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 1987; ISBN 9789127110274. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. A salutogenic interpretation of the Ottawa Charter. Health Promot. Int. 2008, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, K.; Sangster, M.; Konijnendijk, C.C. Forests, trees and human health and well-being: Introduction. In Forests, Trees and Human Health; Nilsson, K., Sangster, M., Gallis, C., Hartig, T., de Vries, S., Seeland, K., Schipperijn, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-90-481-9805-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson, Å.; Ottosson, M. Naturkraft. Om Naturens Lugnande, Stärkande och Läkande Effekter; Wahlström & Widstrand: Falun, Sweden, 2006; ISBN 9789146212348. [Google Scholar]

- Souter-Brown, G. Landscape and Urban Design for Health and Well-Being; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781315762944. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; ISBN 0521349397. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; ISBN 9780674074422. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Natural versus urban scenes: Some psychophysiological effects. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 523–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mang, M.; Evans, G.W. Restorative effects of natural environmental experiences. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Staats, H. The Restorative Qualities of Being Alone with Nature. In The Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and Being Alone; Coplan, R.J., Bowker, J.C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Beddington, J.; Cooper, C.L.; Field, J.; Goswami, U.; Huppert, F.A.; Jenkins, R.; Jones, H.S.; Kirkwood, T.B.L.; Sahakian, B.J.; Thomas, S.M. The mental wealth of nations. Nature 2008, 455, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molcar, C.C. Place Attachment and Spiritual Well-Being across the Lifespan. In The Importance of Place and Home to Quality of Life; Seattle Pacific University: Seattle, WA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9783639060300. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, A.D.; Peterson, C. The Health Benefits of Nature: Introduction to the Special Section. Appl. Psychol. Health Wellbeing 2011, 3, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, M. Understanding Illness: Using Drawings as a Research Method. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; SAGE Publising: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4129-7212-3. [Google Scholar]

- Holme, I.M.; Solvang, B.K. Forskningsmetodik. Om Kvalitativa och Kvantitativa Metoder; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 1997; ISBN 9789144002118. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Att göra Grundad teori—Problem, Frågor och Diskussion (Doing Grounded Theory—Issues and Discussions); Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-91-633-7008-3. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine de Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 1967; ISBN 0-202-30260-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wigg, U. Att analysera livsberättelser. In Handbok i Kvalitativ Analys; Fejes, A., Thornberg, R., Eds.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014; pp. 198–215. ISBN 978-91-47-11165-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson, J.; Lavesson, L.; Pinzke, S.; Grahn, P. The Significance of Experiences of Nature for People with Parkinson’s Disease, with Special Focus on Freezing of Gait—Necessity for a Biophilic Environment. A Multi-Method Single Subject Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 7274–7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What is the Best Does of Nature and Green Exercise for Improving Mental Health? A Multi-Study Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korpela, K.; Hartig, T. Restorative qualities of favorite places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K. Adolescents’ favorite places and environmental self-regulation. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies. An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781473948907. [Google Scholar]

- Birren, F. Color psychology and color therapy. In A Factual Study of the Influence of Color on Human Life; Martino Publishing: Eastford, CT, USA, 2013; ISBN-10: 1614275130. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).