Representing the Reading Experience. The Reader’s Education through Picture Books †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

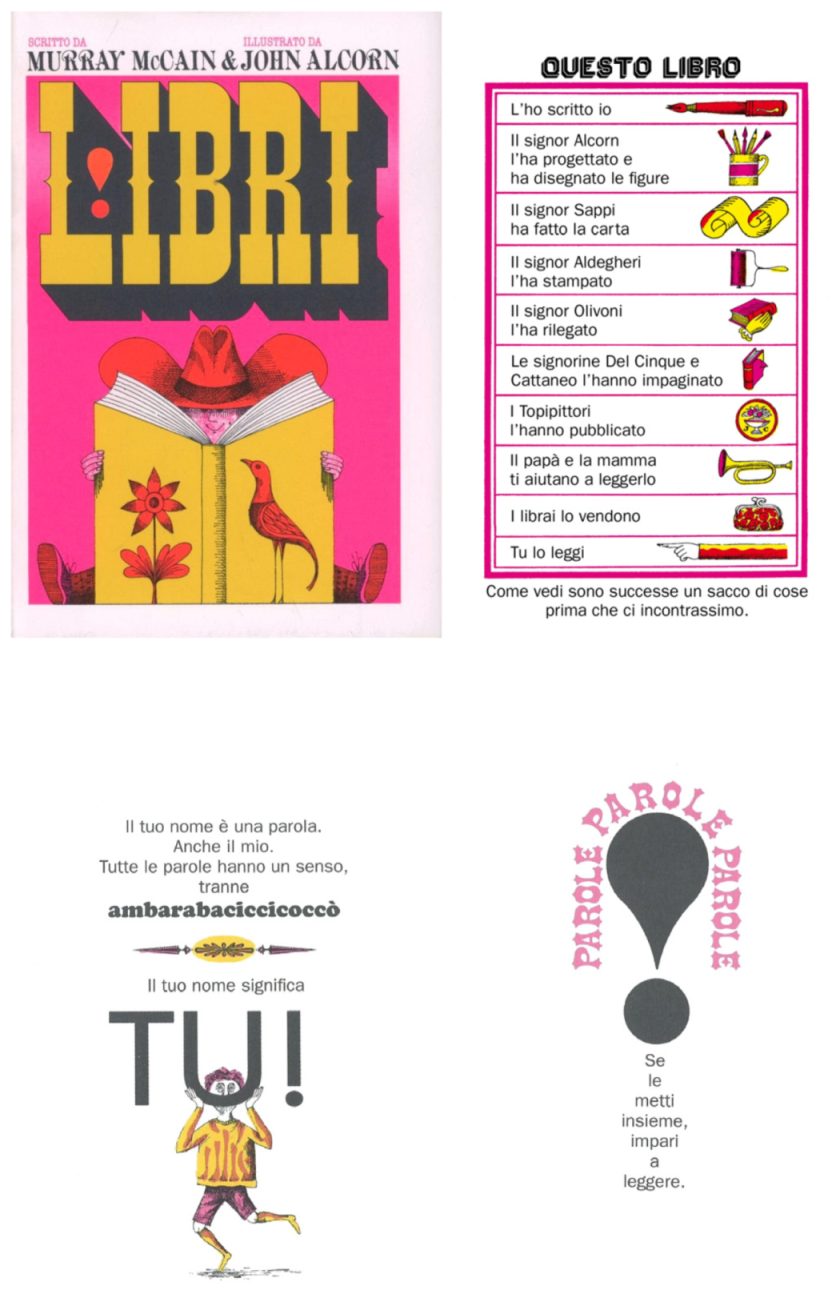

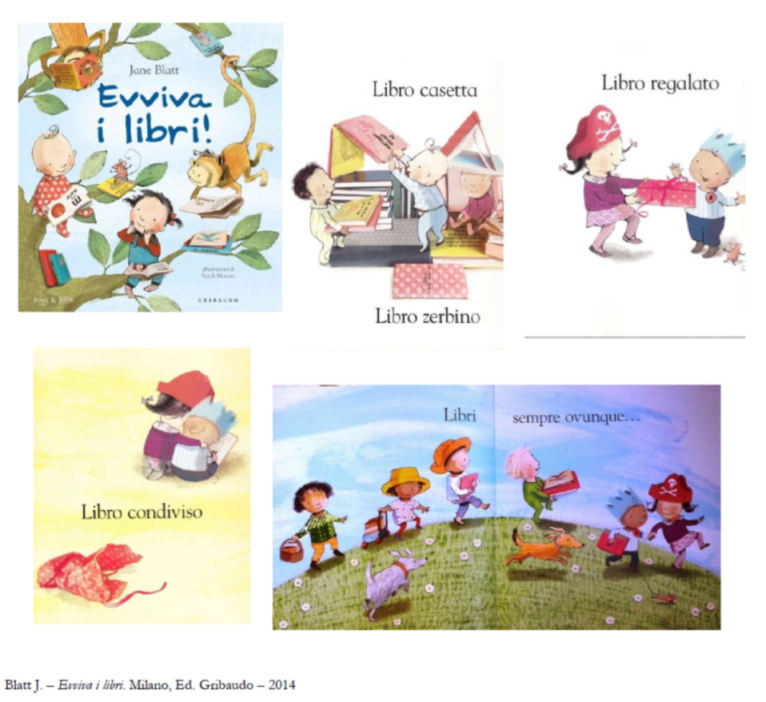

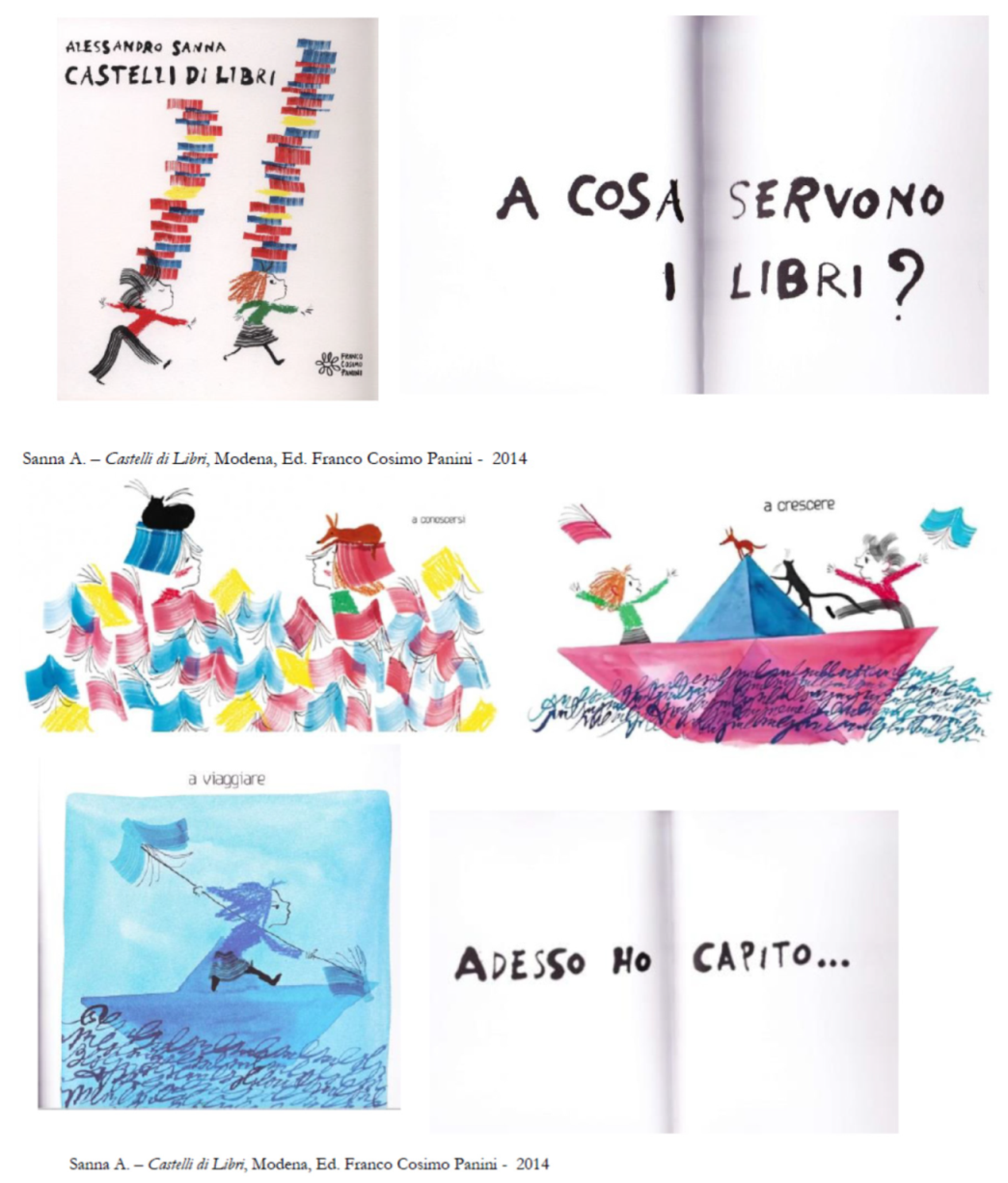

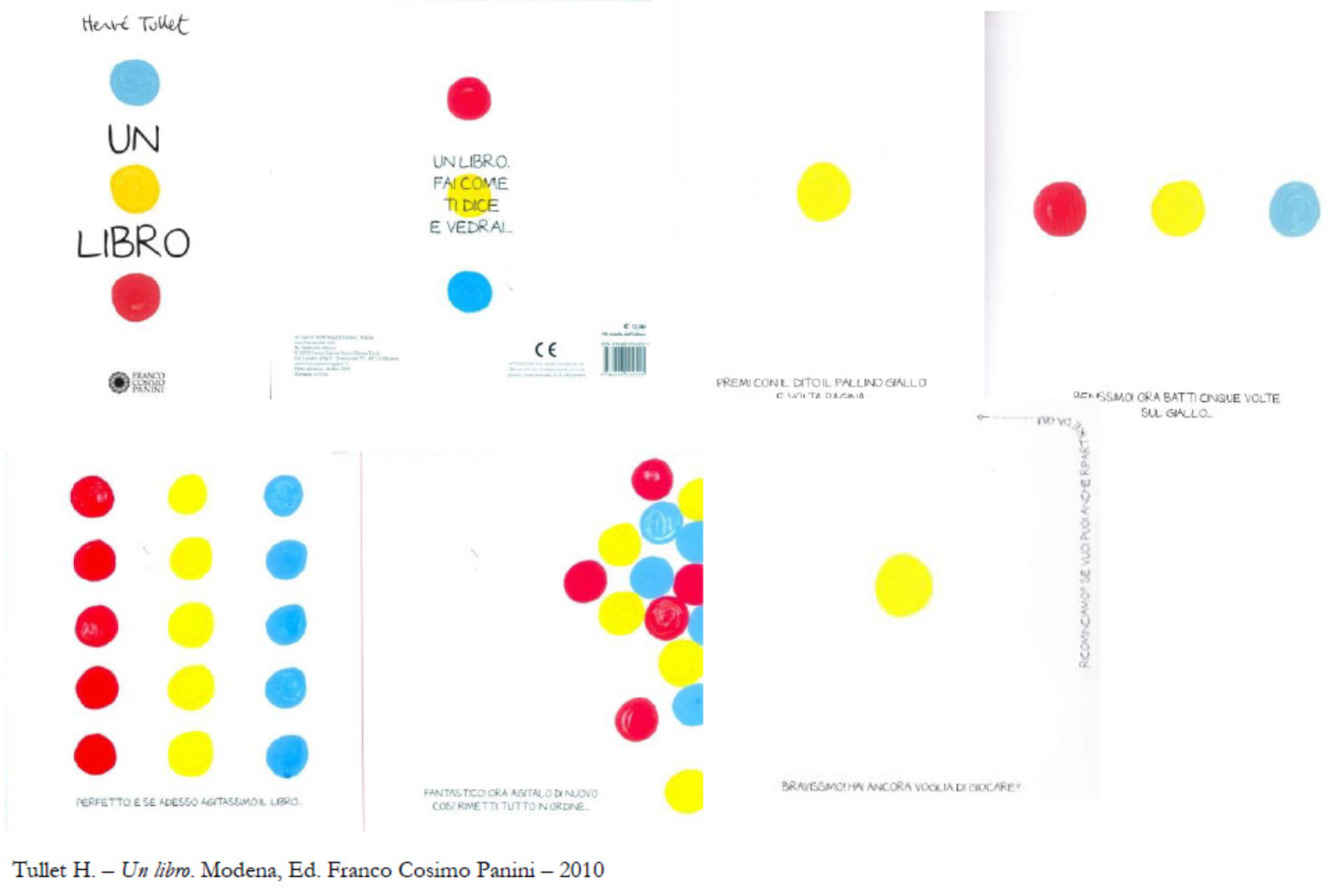

2. The Picture Book as Object and Process

3. Stories within Stories

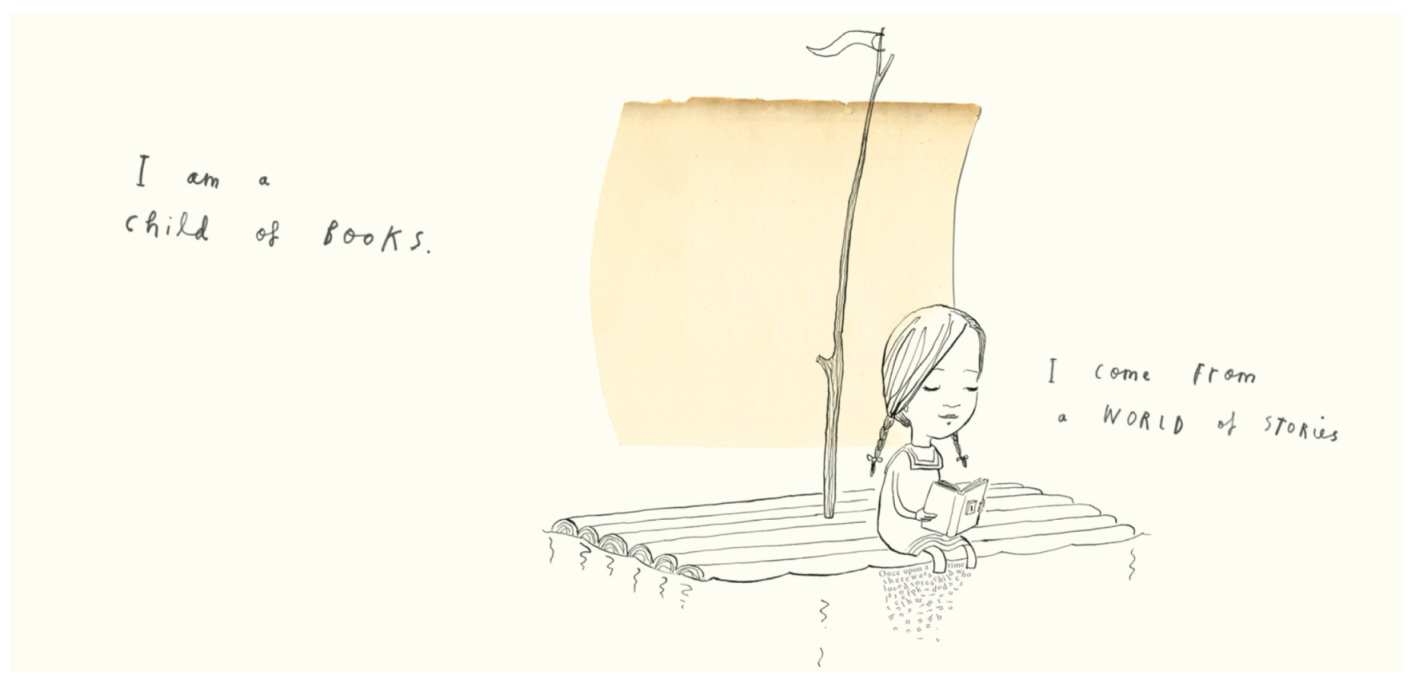

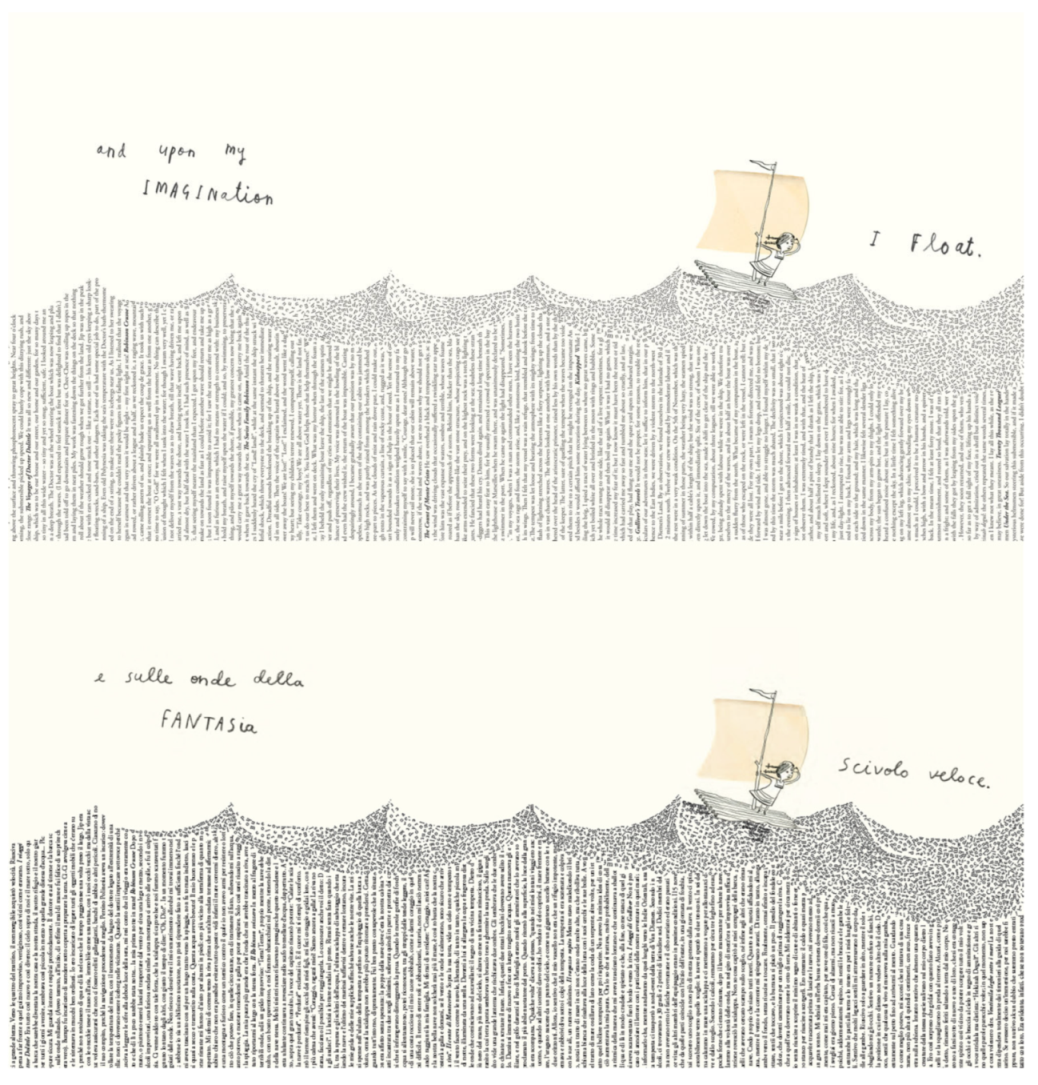

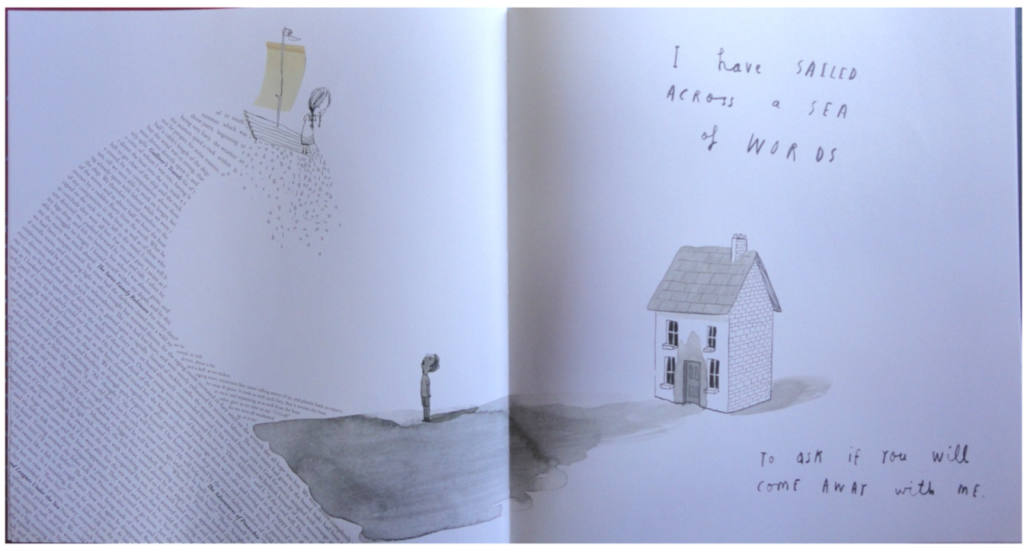

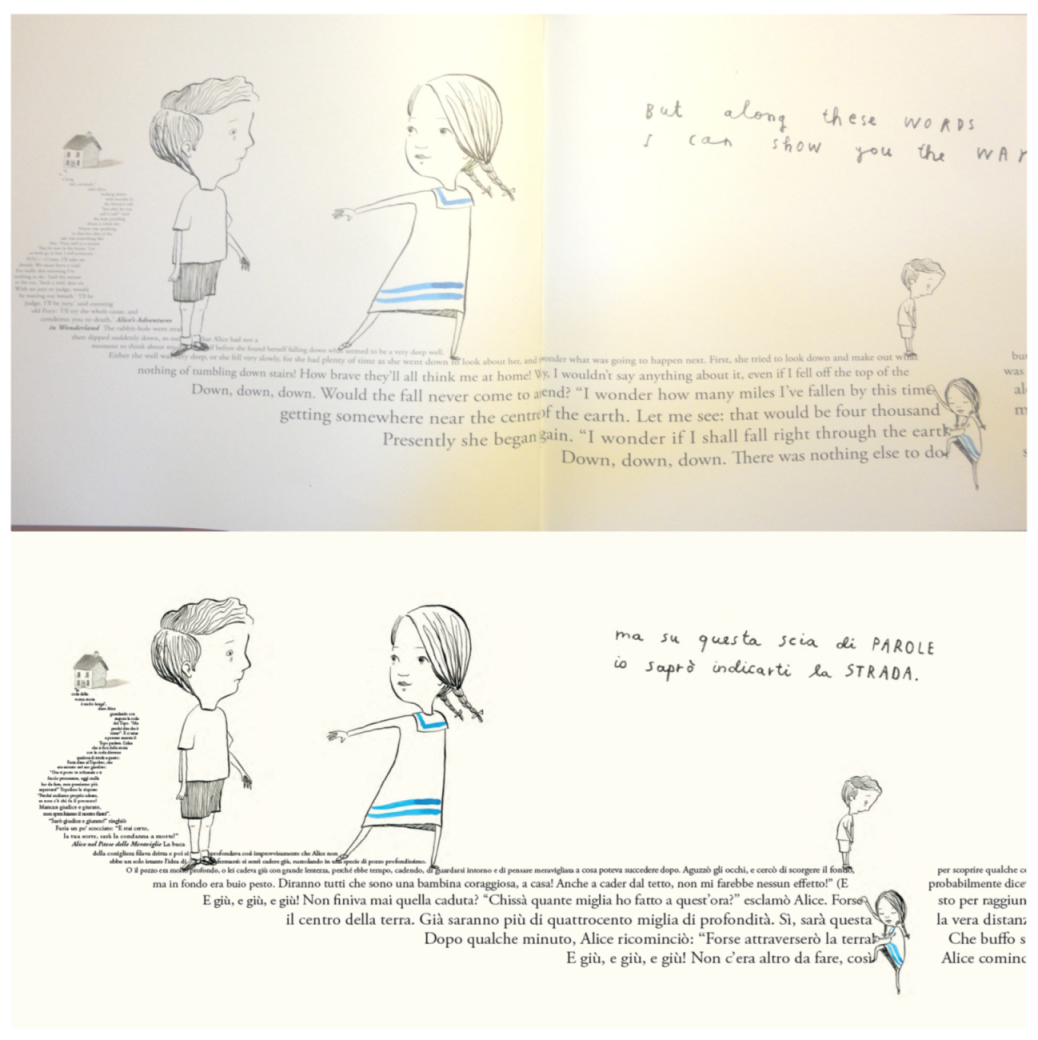

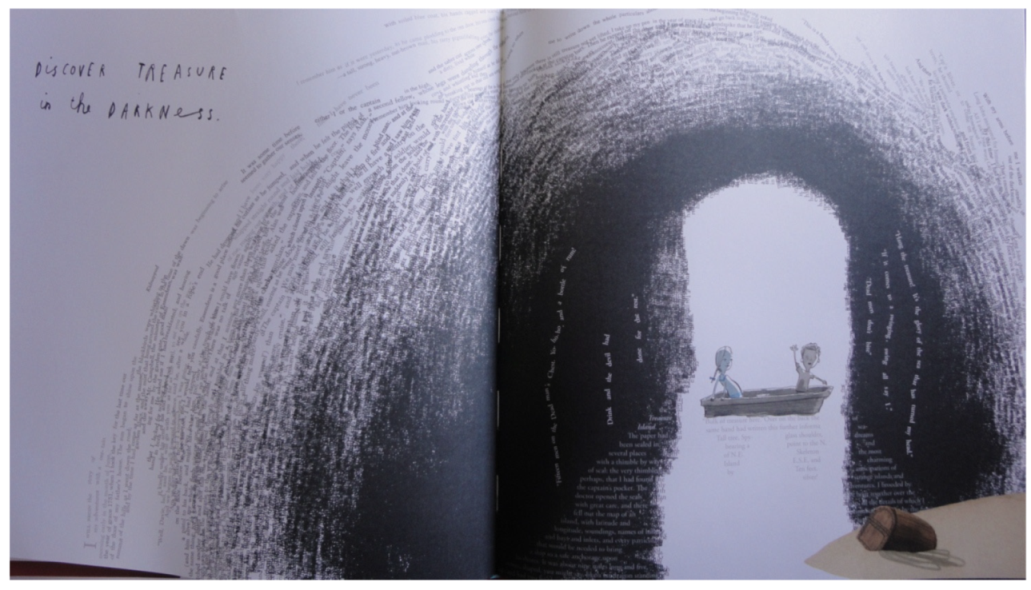

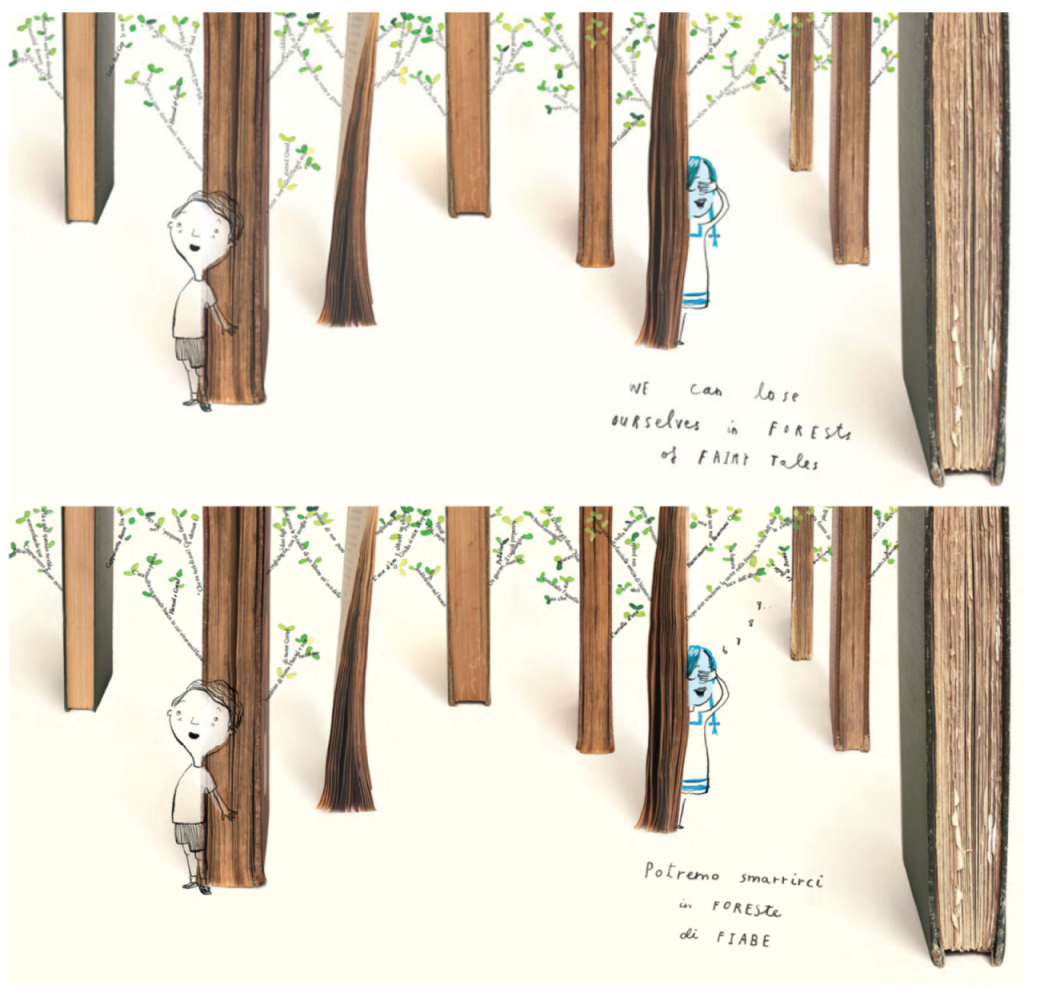

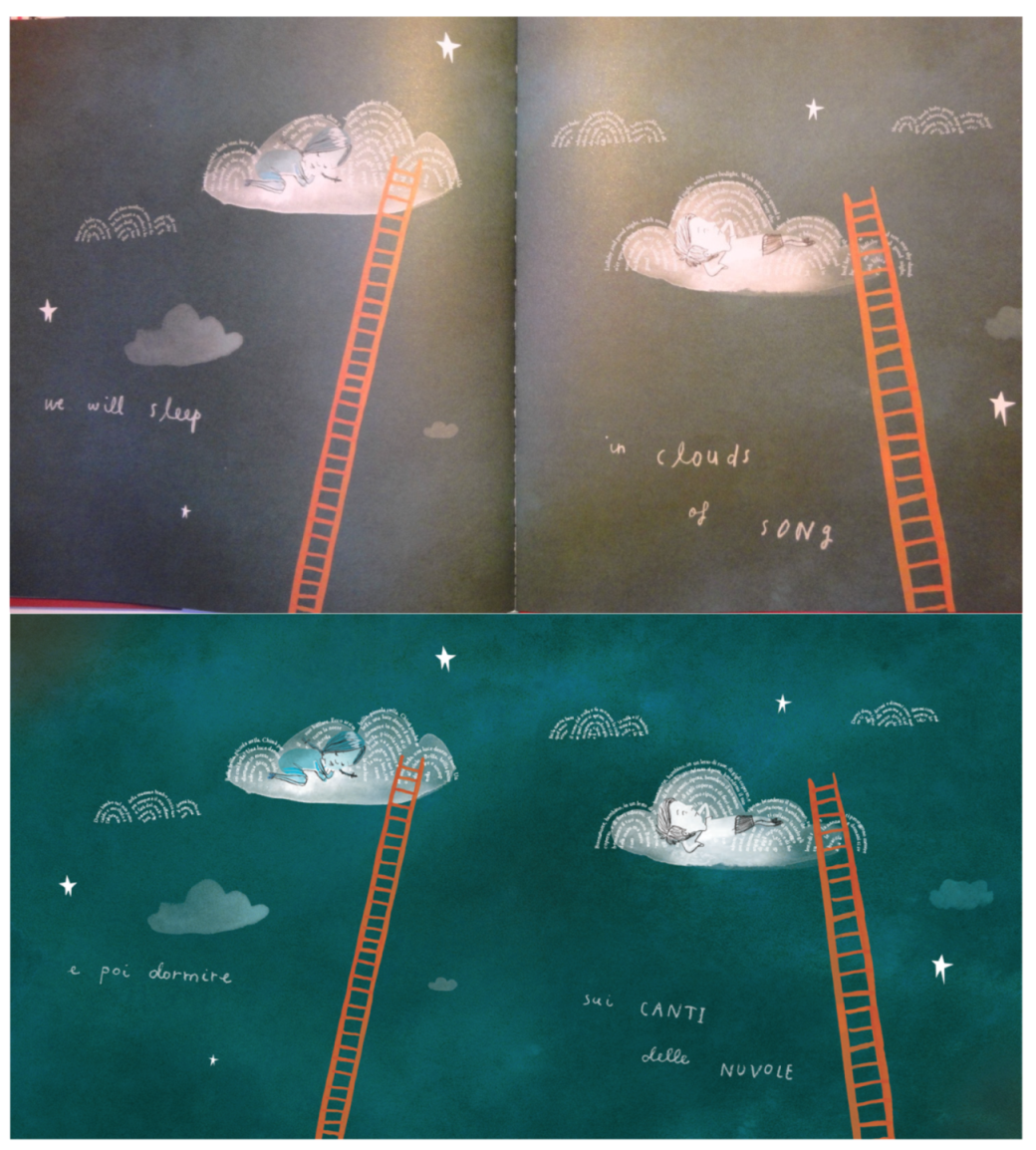

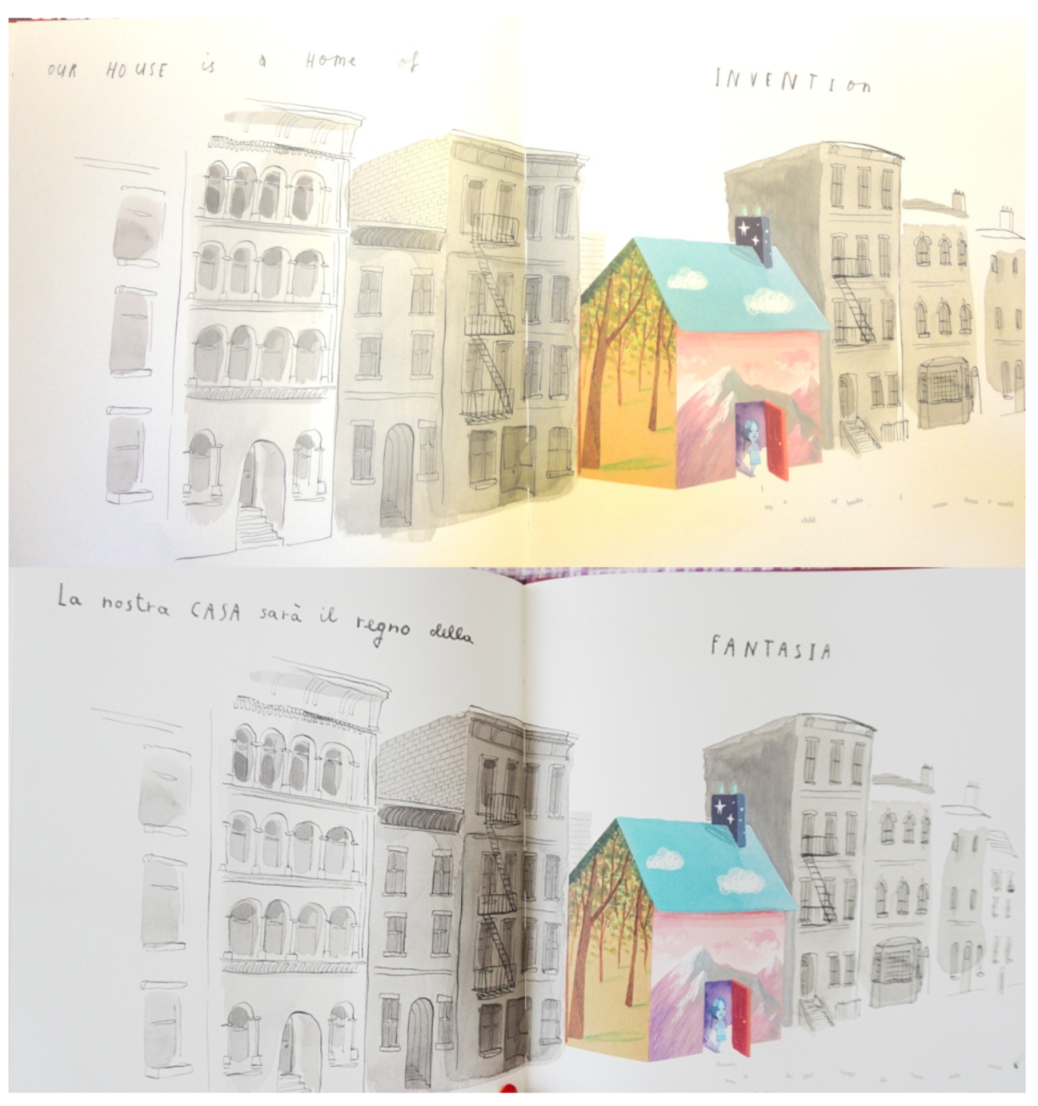

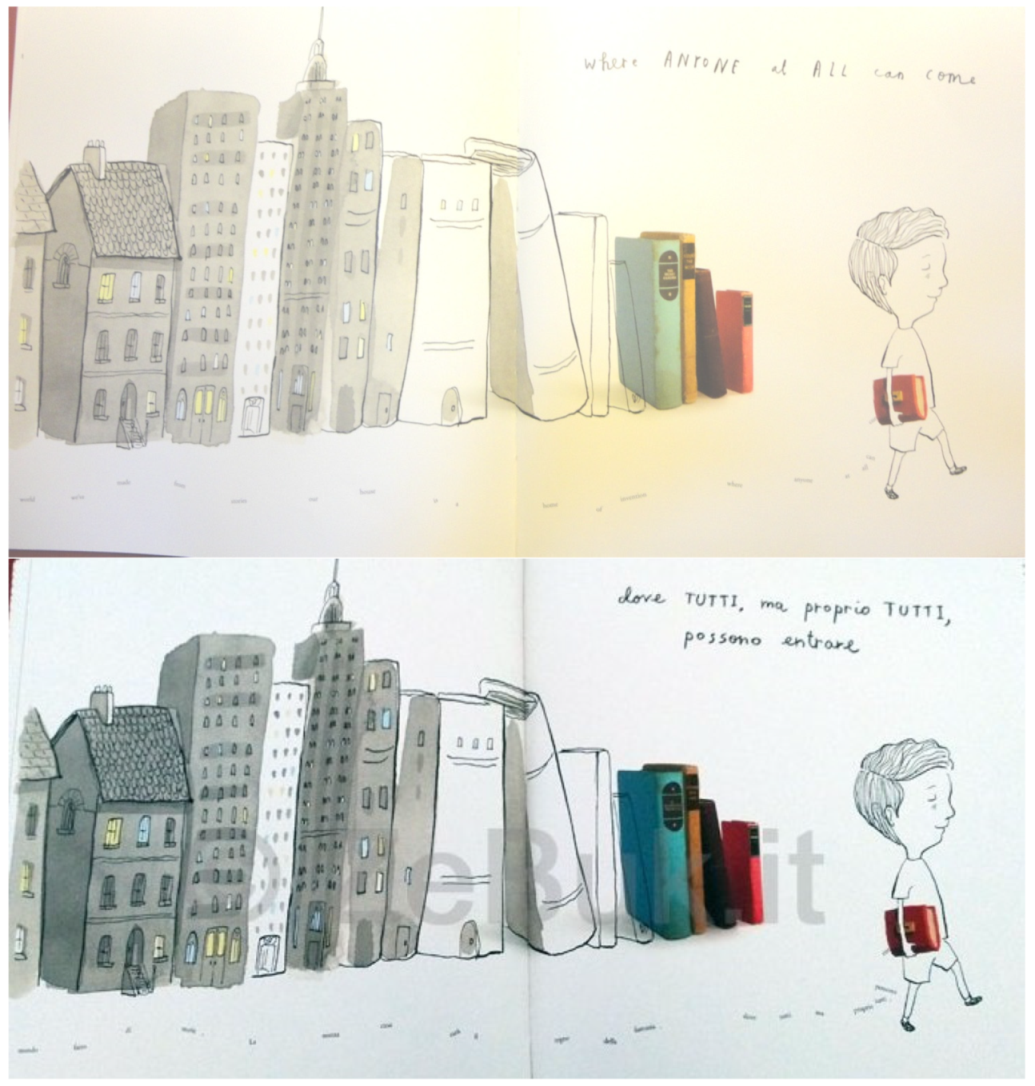

4. A Child of Books: An Original Synthesis

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Calvino, I. Se Una Notte D’Inverno Un Viaggiatore, 1st ed.; Bompiani: Milano, Italy, 1979; ISBN 880649130. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. Lector in Fibula, 1st ed.; Bompiani: Milano, Italy, 1979; ISBN 8845248062. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, A. Siamo Quello Che Leggiamo, 1st ed.; Equilibri: Modena, Italy, 2011; ISBN 9788890051869. [Google Scholar]

- Huck’s, C. Children’s Literature, 1st ed.; McGraw Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780073378565. [Google Scholar]

- Nodelman, P. The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature, 1st ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780801889806. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell George, K. Libro! 1st ed.; Ill. Smith M. Trans. Valentino Merletti R.; Interlinea: Novara, Italy, 2006; ISBN 9788882125523. [Google Scholar]

- Santucci, L. La Letteratura Infantile, 3rd ed.; Boni Editore: Bologna, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McCain, M. Libri! 1st ed.; Ill. Alcorn J.; Topipittori: Milano, Italy, 2012; ISBN 9788889210901. [Google Scholar]

- Lukehart, W. (2014). Review to McCain, M. (2013). Books! ill. Alcorn, J. School Libr. J. 2014, 60, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt, J. Books Always Everywhere; Ill. Massini, S., Ed.; Nosy Crow: London, UK, 2013; Trans. Evviva i libri! (2014), Gribaudo: Milano, Italy, 2014; ISBN 8858011023. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolajeva, M.; Scott, C. How Picturebooks Work, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 9781138126930. [Google Scholar]

- Campagnaro, M.; Dallari, M. Incanto e Racconto Nel Labirinto Delle Figure, 1st ed.; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2013; ISBN 9788859001621. [Google Scholar]

- Sanna, A. Castelli Di Libri, 1st ed.; Franco Cosimo Panini: Modena, Italy, 2014; ISBN 9788857008004. [Google Scholar]

- Tullet, H. Un Libro, 1st ed.; Franco Cosimo Panini: Modena, Italy, 2010; ISBN 9788857002521. [Google Scholar]

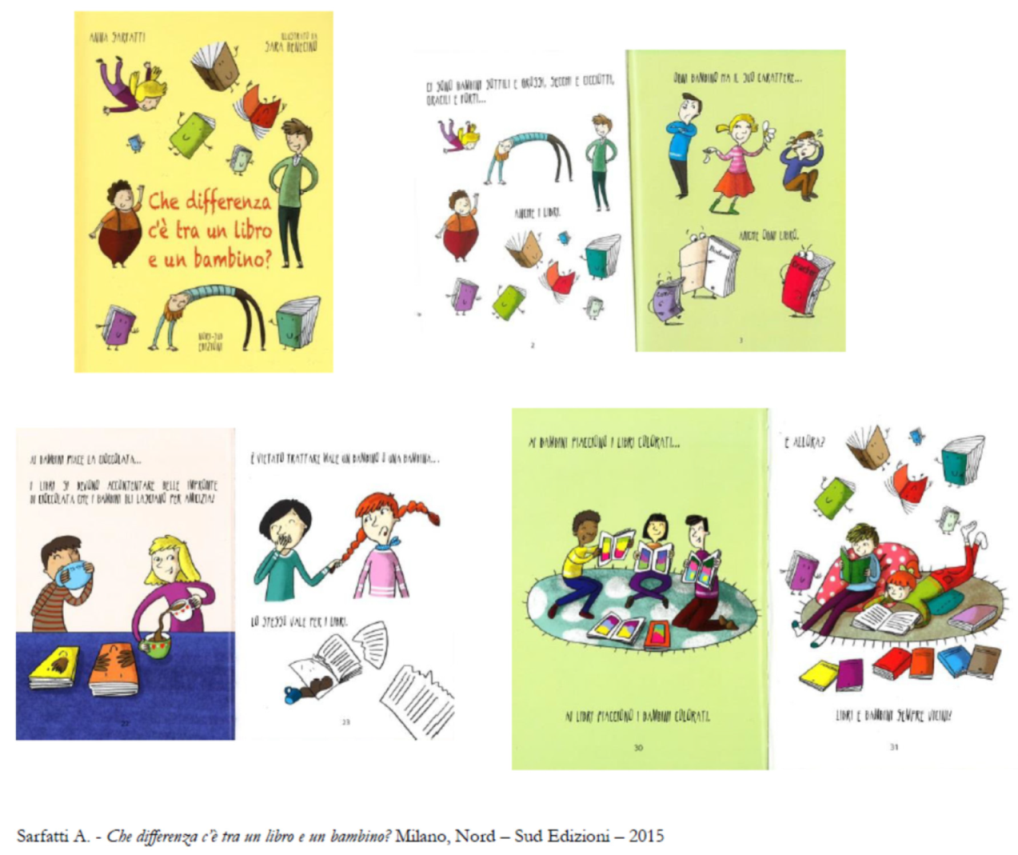

- Sarfatti, A. Che Differenza C’è Tra Un Libro e Un Bambino, 1st ed.; Ill. Benecino, S., Ed.; Nord-Sud: Milano, Italy, 2015; ISBN 9788865264478. [Google Scholar]

- Nodelman, P. Words about Pictures, 1st ed.; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 1990; ISBN 9780820312712. [Google Scholar]

- Colomer, T.; Kümmerling-Meibauer, B.; Silva-Diaz, C. (Eds.) New Directions in Picturebook Research, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780415634168. [Google Scholar]

- Rodari, G. Alice Nelle Figure, 1st ed.; Ill. Cantone, A.L., Ed.; Emme Edizioni: San Dorligo della Valle, Italy, 2005; ISBN 9788847723245. [Google Scholar]

- Boero, P. Una Storia, Tante Storie, 2nd ed.; Einaudi: Trieste, Italy, 2010; ISBN 9788879268110. [Google Scholar]

- Calvino, I. Lezioni Americane, 2nd ed.; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 1993; ISBN 9788804485995. [Google Scholar]

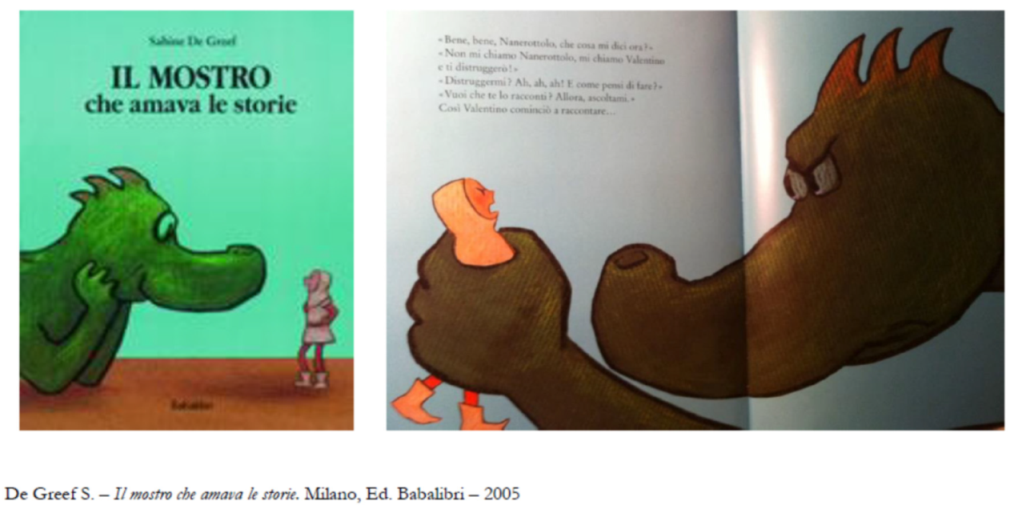

- De Greef, S. Il Mostro Che Amava Le Storie, 1st ed.; Trans. Rocca, F.; Babalibri: Milano, Italy, 2005; ISBN 9788883621062. [Google Scholar]

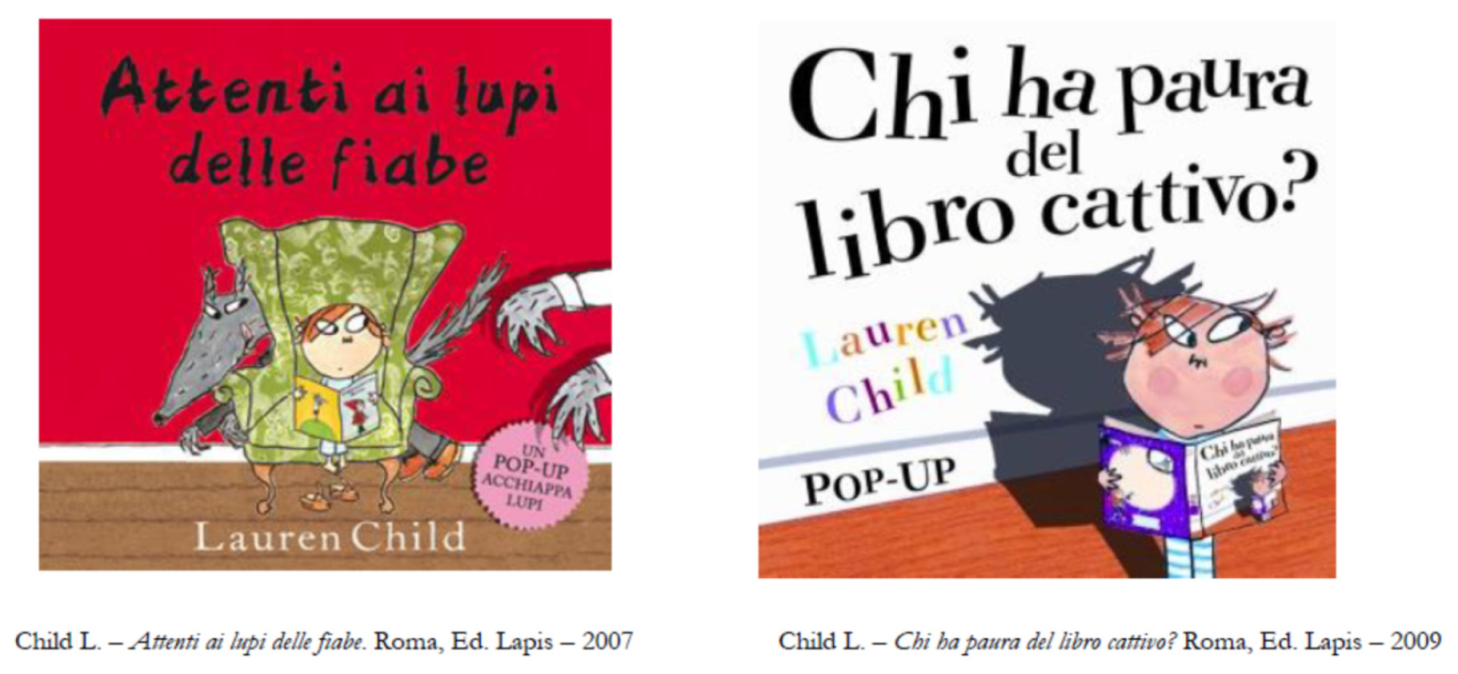

- Child, L. Attenti Ai Lupi Delle Fiabe, 1st ed.; Lapis: Roma, Italy, 2007; ISBN 9788878740662. [Google Scholar]

- Child, L. Chi Ha Paura Del Lupo Cattivo? 1st ed.; Lapis: Roma, Italy, 2009; ISBN 9788878741294. [Google Scholar]

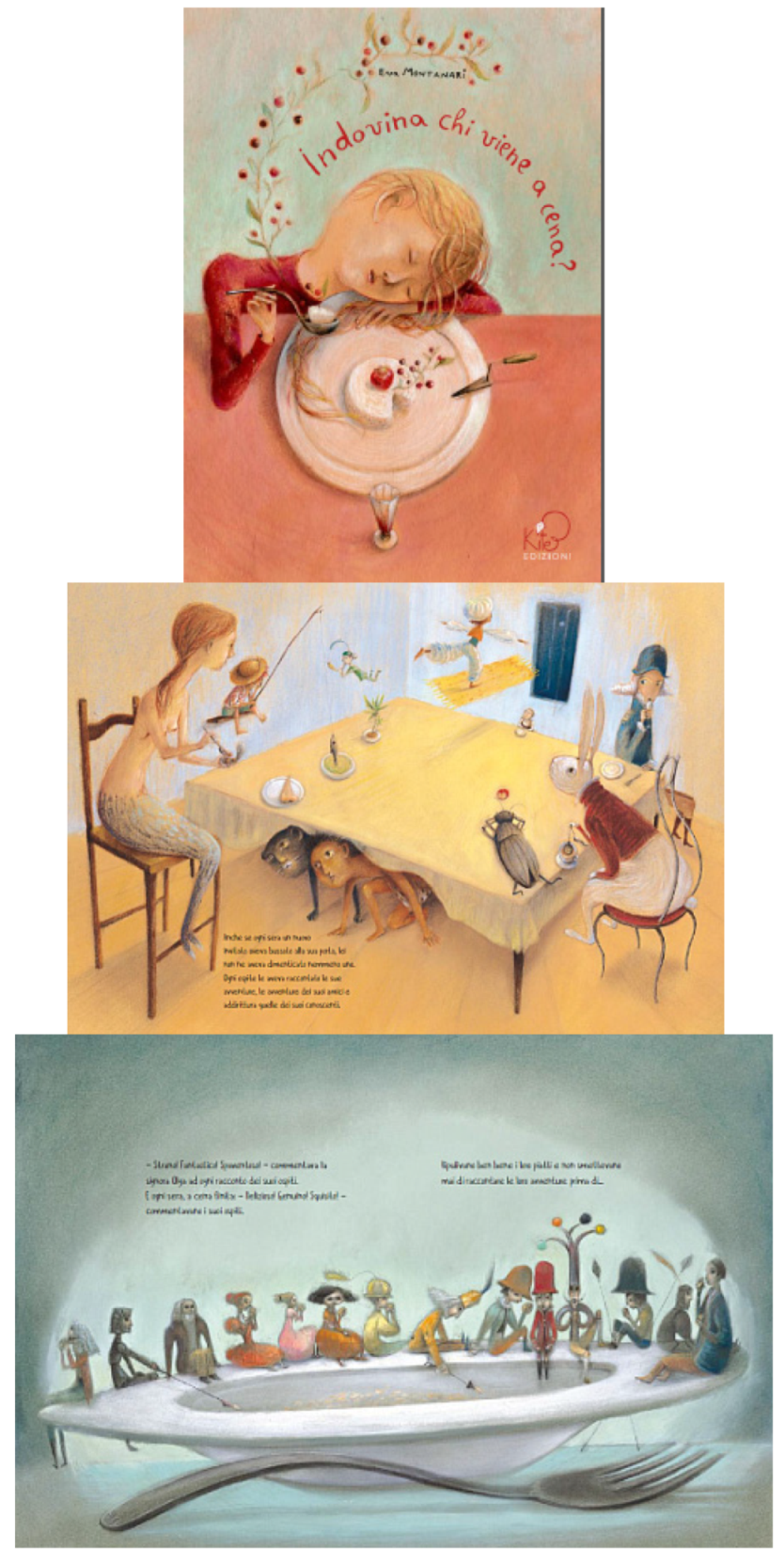

- Montanari, E. Indovina Chi Viene a Cena? 1st ed.; Kite Edizioni: Padova, Italy, 2013; ISBN 9788895799841. [Google Scholar]

- Parmeggiani, R. La Nonna Addormentata, 1st ed.; Ill. Vaz de Carvalho, J., Ed.; Kalandraka: Firenze, Italy, 2015; ISBN 9788895933467. [Google Scholar]

- Fochesato, W. Ospiti speciali. Andersen 2013, 304, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Terrusi, M. Albi Illustrati, 1st ed.; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2012; ISBN 9788843063215. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. (Ed.) Challenging and Controversial Picturebooks. Creative and Critical Responses to Visual Text, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781138797772. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers, O. A Child of Books, 1st ed.; Winston, S., Ed.; Walker Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Riccioni, A. La Bambina Dei Libri, 1st ed.; Lapis: Roma, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9788878745223. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers, O. L’Incredibile Bimbo Mangia Libri, 1st ed.; Zoo Libri: Reggio Emilia, Italy, 2015; ISBN 9788888254968. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M. Proust e Il Calamaro, 1st ed.; Vita e Pensiero: Milano, Italy, 2007; ISBN 9788834317211. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J. Plausible Prejudices: Essays on American Writing, 1st ed.; Norton: London, UK, 1985; ISBN 9780393019186. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, M.; Styles, M. Children’s Picturebooks. The Art of Visual Storytelling, 1st ed.; Lawrence King Publishing: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781856697385. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, L.; Meneses, A.; Gonzales Castillo, G. Analysing the semiotic potential of typographic resources in picture books in English and in translation. Int. Res. Child. Lit. 2014, 7, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbaracki, D.; Geringer, J. Blurred vision: The divergence and intersection of illustrations in children’s books. J. Graph. Nov. Comics 2014, 5, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munari, B. Fantasia, 1st ed.; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 1977; ISBN 9788842011972. [Google Scholar]

- Giandebiaggi, P. Drawing in the creative process. In The Reasons of Drawing. Thought, Shape and Model in the Complexity Management, 1st ed.; Bertocci, S., Bini, M., Eds.; Cangemi Ed.: Firenze, Italy, 2016; pp. 837–842. ISBN 9788849232950. [Google Scholar]

- Quarenghi, G. E Sulle Case Il Cielo, 1st ed.; Topipittori: Milano, Italy, 2007; ISBN 9788889210208. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fava, S. Representing the Reading Experience. The Reader’s Education through Picture Books. Proceedings 2017, 1, 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090864

Fava S. Representing the Reading Experience. The Reader’s Education through Picture Books. Proceedings. 2017; 1(9):864. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090864

Chicago/Turabian StyleFava, Sabrina. 2017. "Representing the Reading Experience. The Reader’s Education through Picture Books" Proceedings 1, no. 9: 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090864

APA StyleFava, S. (2017). Representing the Reading Experience. The Reader’s Education through Picture Books. Proceedings, 1(9), 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090864