Abstract

This paper collects a number of reflections on the use of illustrated books during the first months of life. Reading pictures is a unique experience for each individual, through which early opportunities for social and cultural development are created. It sheds light on a child’s level of development; on what a very small person can do on their own; on the correct tools to assess a child’s type of attention compared to an adult’s; about what happens when a newborn and an adult place a book which is new to both of them at the center of their relationship. The rush to find words in a book ignores its multidimensionality. Nascent readers, with their scrupulous and multifaceted method of living the reading experience, teach themselves and those who comprehend them how a concept emerges and takes form.

1. Introduction. Ethical Tension and Cultural Mediation

This paper collects a number of reflections on the use of the illustrated books during the first months of life. The aim is to increase the critical tools available to approach reading with children in a less spontaneous manner. Those who study childhood literature, in this case illustrated books, should stimulate a wider discussion of reading pictures from birth, in addition to increasing such books’ popularity.

Sean Carroll is considered one of the greatest contemporary scholars of evolutionary develop-mental biology. In a study regarding the human mind, he describes an event which occurred at London Zoo, the day Charles Darwin met the orangutan Jenny. Darwin was struck by the relationship between the keeper and the animal, and impressed by Jenny’s intelligence and attitude towards play. He realised that children were very similar to the specimen and began to observe childhood as a comparative primatologist [1]. Teaching how to read images should immediately awaken contact with our evolutionary history and our human selves. A potential future objective might be to observe children who read images, in the role of comparative primatologist.

Engaging in reading images invites the reader to decode the images both in and out of books, to change their mindset if the opportunity presents itself and to combine ideas, people and previously unseen materials. Let us never forget that books are “things” and that, as Remo Bodei writes, “qual-siasi oggetto è suscettibile di ricevere investimenti e disinvestimenti di senso, positivi e negativi, di circondarsi di un’aura o di esserne privato” [2] (p. 23). Reading images could be the primer for an existence pervaded by physical and mental images, of meaningful and insignificant things.

There are more children who read picture books in the first months of life than is thought. How-ever, little is known about them due to the scarce availability of documentary resources and quantitative data. It would be beneficial to organise frequent exchanges between literacy teachers and academics engaged with the workings of the mind. We would discover that there is a significant amount of work to do and the path that potential researchers would face is a map of new topics whose complexity cannot be addressed without collaboration between various fields and the contribution of those who live the work of educator and coordinator directly.

2. A Golden Age of Picture Books

Children can read and tell a story with a book in their hand before learning to read the alphabet. If they learn to use the letters of the alphabet, it is because they have already acquired familiarity with the interpretation of pictures, among other factors. When we learn to read, we are amazed because we become aware of an astonishing fact: a letter is a picture with specific qualities. It is not self-contained, like a drawing of an apple, a ball or an animal; it is a unit with which you can compose and disassemble words, and play with the written language.

Being born to read is an unassailable fact: human beings are in this world to read any event, not just written stories or even just the pages of books. Despite this, due to habit, being born to read is not a phrase whose meaning is necessarily clear. The tendency has been to reinforce the notion that reading aloud is a dominant factor in effective reading education during early childhood. The image of the (volunteer or professional) reader photographed in the foreground while re-citing a text with a contact microphone seems to have become a symbol. Affectionately authoritarian, unanimously approved, this new figure discards the concept of education for the concept of seduction.

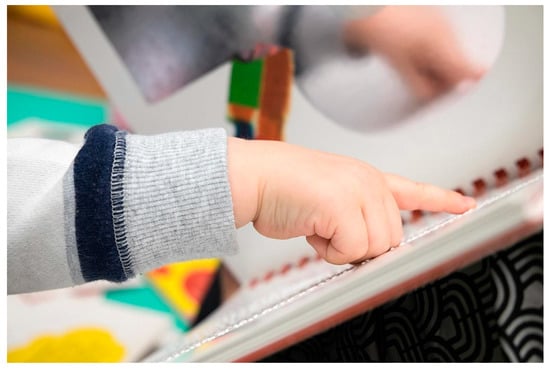

Reading with children is carried out in conditions of ethical tension and cultural mediation, evoking the topics identified here, while initiatives to seduce continue to be confused with initiatives to educate. In the Dichiarazione degli obblighi verso l’essere umano it is stated that, “l’intelligenza, per esercitarsi, ha bisogno di potersi esprimere senza che qualche autorità la limiti” [3] (p. 30). Obligating oneself to take a step back makes space for a scenario that has a right to emerge, which adults often inadvertently overwhelm or disturb: a child chooses an object conceived to enter in direct communication with them without words and without dependence on an adult, because it perfectly reflects their universal linguistic model, their non-written and not strictly verbal code, their degree of autonomy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Picture by Elisa Vettori, “Ku-Ku! Leggere le figure dalla nascita” for the children of Asilo Nido Pineta In Crescendo, Rome, Italy, care of Giulia Mirandola.

“La fotografia, in quanto scrosta i secchi involucri della visione abituale, crea un’altra maniera di vedere” [4] (p. 87) writes Susan Sontag. Likewise, the language of illustrated books, as well as creating other ways of seeing, could become an instrument for many adults to peel away their own way of seeing and use their gaze like the lens of a camera. Sontag describes the result of these operations as an evaluation of the world [5] (pp. 77–78). This is why reading pictures is a unique experience for each individual, through which early opportunities for social and cultural development are created. As evidence of the favourable factors, we are surrounded by good illustrated books. The confidence of certain official bodies has reached the point that, “We’re living in a ‘golden age of picture books’ according to the American Book Producers Association and Publishers Weekly” [6] (p. 36). Those who live in the world of education, therefore, have the responsibility of living these days of growth with the best available literature on the market and in public libraries.

Questions are a classic starting point to explore the depth and range of a given reasoning. Since 2012, I have had the pleasure of collaborating with children under the age of 24 months thanks to Ku-Ku! Leggere le figure dalla nascita (Ku-Ku! Reading Pictures from Birth) [7], the literacy project which brought us together. The core of this experience can be summarised in three questions:

- What mental images and narrative sequences form the cradle of a visually literate and linguistically evolved civilisation?

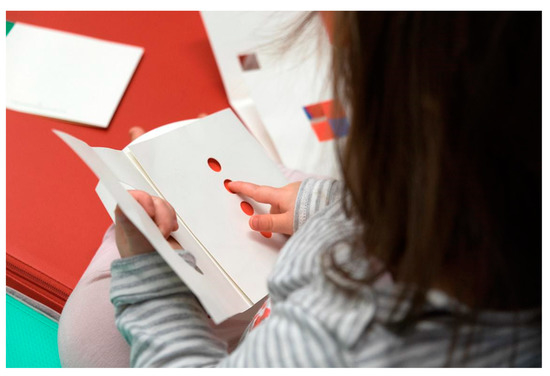

- How can we now be supported by the reading of illustrated books to deepen our relationship with visual narratives and to recognise a specific culture in narrative pictures which is of extreme interest to those who live the educational experience? (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Picture by Elisa Vettori, “Ku-Ku! Leggere le figure dalla nascita” for the children of Asilo Nido Pineta In Crescendo, Rome, Italy, care of Giulia Mirandola.

Figure 2. Picture by Elisa Vettori, “Ku-Ku! Leggere le figure dalla nascita” for the children of Asilo Nido Pineta In Crescendo, Rome, Italy, care of Giulia Mirandola. - How can reading pictures affect the imaginative capacity and positively influence the stimulation of skills needed to produce a truly prosperous culture?

The list of topics below reflects the underlying motives of my research on reading wordless, illustrated and photographic books, with people under the age of 24 months.

- What it means to read: reading books with pictures from birth draws attention to the question of what it means to read, giving rise to more specific, general and individual questions.

- The intensification of reading practice from birth: more systematic initiatives can be a catalyst to improve the early childhood services offered by public libraries and to restructure the experience of reading illustrated books with educators and coordinators.

- Study and practice reading methods other than reading aloud: illustrated books allow us to read differently from reading aloud, especially with regard to very young readers. In addition, the same books are valid tools for recognising aspects that do not conform to this mode of reading.

- Deepening of aspects related to multi-sensory perception: visual reading is not an experience that only engages sight, as perception does not solely rely on visual perception. Illustrated books are a starting point for deepening these complex arguments.

- Multidisciplinary research method: focusing attention on specific issues and trying to establish connections with sources other than childhood literature contributes to producing a more evolved culture on the use of early childhood illustrations. Some areas of reference: cognitive sciences; natural sciences; philosophy; linguistics; play; law and ethics; design; psychology; music.

- Photographic documentation as a further component of observation: photography allows you to reflect on the reading activity after it has ended; photography, in this case, is an operation through which to document and read a situation in detail. Producing directed and high quality images, which can be obtained by working together with professional photographers motivated to work in a team, is a valuable resource.

3. Read the World

I was not looking for it. It appeared in the midst of other subjects, like a rock on a beach where there are many stones, when I recognised in it an eloquent metaphor. This is the Swimming Eye, an illustration by Isidro Ferrer designed for the cover of a dossier on Madrid’s candidacy for the 2020 Olympic Games [8]. The eye on a woman’s face is represented by the icon of a per-son swimming in freestyle. When we read pictures, we arrange our mental instruments for a type of vision which is different to when we use our sight to take an object or cross a road ensuring no cars are passing, or when we read words. The eye is a swimmer when it slips into the seas of images. It floats, goes underwater, dives, is master of its breathing and trajectory, seeks the pleasure of moving like a fish, and detaches itself from those who cannot swim. I am interested in observing how adults and children read pictures because their rapport brings extratextual elements that can be seen as evidence that they do something different to mutually entertaining one another. I’ve seen confident people drown unaware and never come back to shore; others pretend to breathe properly; others hold their breath and give up; others flail around wildly, moving only the water; others make modest and progressively larger strokes; others gain unexpected speeds and cover unexpected distances; others dive with courage. The important thing, ultimately, is to decide what the value is in learning a new thing, to choose whether to endure waiting for perfection over time or to leave the lane free for those who want to train, improve and head for the open sea.

Martha Nussbaum states that the capacity for imagination influences a society’s degree of economic prosperity and democracy [9]. According to the scholar, cultivating the imagination and the humanistic spirit from infancy contributes to human development. Reading books with pictures does not make children better or worse. If anything, it is a way to access our high level cognitive and imaginative ability, a leap into “il gioco incessante tra il mondo e la sua rappresentazione” [10] (p. 28).

Before being an illustrated image, a figure is alive: it is ourselves and the other; faces, hands, voic-es and everything around us that we call nature, animals and things. An illustrated book is an ob-ject that reminds us of the problems associated with visual reproduction and cognitive operations. From birth onwards, teaching ourselves to read images in books involves the effort of teaching ourselves to read images out of books. As Giuseppe di Napoli writes: “L’etimo eidos (forma figu-ra), da cui discende il termine idea ha la stessa radice di eidein (vedere) e, per i greci, il perfetto di vedere oìda, significa “io so” (perché ho visto). La visione è la forma di conoscenza principale della nostra cultura: tutta la storia, non solo dell’arte, ma delle scienze, della biologia, della zoologia, della botanica, potrebbe essere riscritta attraverso la storia della visione.” [11]

Reading an illustrated book may seem like a paradoxical experience: our senses are engaged in an activity related to visual and tactile perception; internally we are immersed in a spatial and tem-poral exploration with abstraction, immateriality, subjectivity, the production of brainwaves, the orientation of attention and emotions at its core. There is no fixed (or moving) image in the world that does not seriously address the problem of invisibility, the appearance of what is not seen and how to communicate with these different types of reality (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Picture by Elisa Vettori, “Ku-Ku! Leggere le figure dalla nascita” for the children of Asilo Nido Pineta In Crescendo, Rome, Italy, care of Giulia Mirandola.

Humans live through an unrepeatable age, at the beginning of existence, when all images and words appear for the first time on Earth in an individual’s personal culture. During this time, we usually only have a few months of life and two million years of evolutionary inheritance, which, if without serious genetic malformation, characterises us without inequality. The ability to express oneself is essentially based on the discovery that we can create images and words that are born in us and live with us from images and words born before us. Communication with oneself and with others is a conquest that does not depend on the number of words we use in a sentence or the volume of our voice. Reflecting on the power of images and how they function provokes an open revaluation of what it means to read. The question is not of reading, but of reading the world.

Munari said, in short, that everyone sees what they know [12], from which it can be inferred that what we do not see what we do not know. The problem is largely influenced by the fact that a the-ory on these themes, with reference to the language of illustrated books, has yet to be formulated. Why should the assumption of a theoretical perspective on the subject be taken into considera-tion? Perhaps to continue not knowing what we do not know, but in a different way; to recognise that we are in a theoretical tradition; to discover new theories. Reflecting on the reading of pic-tures, as we are doing, raises some questions that could be put to a linguist, if one were now before us: what is the relationship between the ability to read pictures and the ability to conceptualise unknown experiences, such as the origin of life or its extinction? Does being a strong reader of books with pictures result in a greater availability of metaphors within narrative, oral, gestural and written skills? How could it be scientifically proven?

Reading with very small children sheds light on a child’s degree of development; what a very small person can do on their own; on the correct tools to assess a child’s type of attention compared to an adult’s; about what happens when a newborn and an adult place a book which is new to both of them at the centre of their relationship. Alison Gopnik offers fundamental advice for those who read illustrated books with small children: “piuttosto che decidere su quali parti del mondo puntare lo sguardo, sembra che i bambini lascino che sia il mondo a decidere per loro. E anziché definire su quale punto focalizzare l’attenzione e inibire le distrazioni, restano consapevoli di una porzione più estesa di realtà. Non si limitano a cogliere solo i dati relativi a specifici oggetti di loro utilità, ma tutti quelli che li circondano, soprattutto se nuovi. E, ovviamente, ai loro occhi molte più informazioni risultano tali. Questa capacità di mantenere un livello di attenzione generico rende i bambini abilissimi nell’apprendimento” [13] (pp. 134–135).

I have seen and photographed 8-month-old children reading the Little Eyes series by Katsumi Komagata on their own with both scientific precision and ancient gestures. With some newborns, reading sessions can exceed thirty minutes, sometimes forty. Adults, on average, have no faith in this possibility and treat these materials indecisively until a child’s eyes are no longer open. As we read illustrated books, we play with multisensory perception and the relationship between body and thought. We become a sensitive listening space and a place for a unique relationship.

4. Ku-Ku! Reading Pictures from Birth with the Children of the Asilo Nido Pineta in Crescendo in Roma

In 2016, I asked photographer Elisa Vettori to collaborate on a project about reading from birth, to start in early 2017. We went to a nursery school every day for a week to carry out reading activities with children aged 7 to 13 months in the presence of their educators. Each session lasted 45 minutes. The groups consisted of eight children and two educators at a time. I had the role of mediating the relationship between the books and the children, the photographer took pictures of the situation. Elisa Vettori is not specialised in baby photography, she is a freelance photojournalist used to watching people and landscapes and photographing them with satisfying results. To obtain documentation for deeper analysis, it was necessary to use directed and high-quality images (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Picture by Elisa Vettori, “Ku-Ku! Leggere le figure dalla nascita” for the children of Asilo Nido Pineta In Crescendo, Rome, Italy, care of Giulia Mirandola.

The experience took place at the Asilo Nido e Scuola Materna Pineta In Crescendo in Rome. The reading sessions took place in the presence of educators who had attended a training day where the materials used were presented. The books used were seen by the educators for the first time. Titles and authors were selected without considering the age range, theme or date of publication, instead relying on other criteria:

- The opportunity for each child to interact autonomously with the book object;

- The opportunity to conduct reading times of at least thirty minutes;

- The opportunity to perceive in the positive experience of reading the positive experience of play;

- Opportunities for each child to guide the adult in the discovery of the book object;

- Opportunities for each child to reduce their dependent relationship on the adult by discovering objects which are new to both;

- The opportunity to experience reading as a cognitive experience instead of entertainment;

- The opportunity to positively experience the relationship with very different objects from the point of view of form and content;

- The opportunity to introduce into the family environment cultural elements that were previously not part of it;

- The opportunity to change reading modes with the children;

- The opportunity to change mentality when referring to reading from birth;

- The opportunity to share reading moments with children who have different ages and native languages.

In particular, I would like to recall point G: The opportunity to positively experience the relation-ship with very different objects from the point of view of form and content.

The examples we used include:

- Small [14,15]/Medium [16,17]/Large format books [18,19]

- Books with several pictures [20,21]/Books with few figures [22,23]

- Recently published [24,25]/Classic books [26,27]

- Books by Italian publishing houses [28]/Books by foreign publishing houses [29]

- Play books/Popup books/Books with holes [30,31,32]

- Visual cards [33,34,35]

- Books explicitly aimed at multisensory experience [36,37,38]

- Colour books [39,40]/Black and white books [41,42,43]

- Books with few pages [44,45]/Books with several pages [46,47]

- Photo books [48,49,50]

I did not think it necessary to create a specific category for so-called wordless books, believing it more profitable to consider other book sets.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

There is a multitude of books read by children before they know the language (Figure 5). Of these, a limited percentage is made up of so-called tactile books and in only twelve cases they are I prelibri, that is, pre-books. This article urges us to engage in the activity of reading from birth equipped, enjoying the favourable wind currently blowing on design and editorial production.

Figure 5.

Picture by Elisa Vettori, «Ku-Ku! Leggere le figure dalla nascita» for the children of Asilo Nido Pineta In Crescendo, Rome, Italy, care of Giulia Mirandola.

The breadth of editorial offerings and the continued expansion of books marketed for children in specific circumstances reduce the problem of what to read, in others it amplifies it. In addition, the constraint between reading and how to read seems to reach crisis level when faced with read-ing with very small children. With a speed that leaves adult attention spans behind, children who read, as they read, tell us who they are. They read, like adults, accompanying the examination of the text with the index finger resting on the page; with sounds and timely gestures, comment on their impression when they discover a given element; they widen their eyes because they see something for the first time and from there, instantly, it enters into their thoughts; they read countless times, not just once or twice, as adults tend to do in front of a book for readers of their age, because the object is interrogated with all the senses on each of its parts and this requires time, waiting, practice. This range of information traces the outline of a more accurate and demanding way of working with books read by children to adults.

The rush to search for words in a book ignores its multidimensionality. Nascent readers, with their scrupulous and multifaceted method of living the reading experience, teach themselves and those who comprehend them how a concept emerges and takes form.

Extended References

- Bruno, N.; Pavani, F.; Zampini, M. La percezione multisensoriale, 1st ed.; Società editrice il Mulino: Bologna, Italia, 2010; ISBN 88-15-13852-1.

- Munari, B. Il castello dei bambini di Tokyo, 1st ed.; Edizioni E. Elle: Trieste, Italia, 1995; ISBN 88-7926-186-X.

- Ingold, T. Ecologia della cultura, a cura di Grasseni, C.; Ronzon, F. Meltemi editore: Sesto San Giovanni (MI) 1st ed.; Italia, 2016; ISBN 88-8353-706-6.

- Camuffo, G.; Dalla Mura, M. EDDES/1 Design e apprendimento creativo. Questioni ed esperienze, 1st ed.; Edizioni Guerini e Associati: Milano, Italia, 2017; ISBN 88-6250-663-2.

- Honegger Fresco, G. Dalla parte dei bambini. La scuola dall’obbligo all’oblio, 1st ed.; l’ancora del mediterraneo: Napoli, Italia, 2011; ISBN 88-8325-294-5.

- Montale, E. Nel nostro tempo, 1st ed.; Rizzoli Editore: Milano, Italia, 1972.

- Kentridge, W. Sei lezioni di disegno, 1st ed.; Johan & Levi Editore: Cremona, Italia, 2016; ISBN 88-6010-174-7.

- Bruno, G., Superfici. A proposito di estetica, materialità e media, 1st ed.; Johan & Levi Editore: Cremona, Italia, 2016; ISBN 88-6010-179-2.

- Springer, A. S.; Turpin, E. a cura, Fantasies of the Library, 1st ed.; K. Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2015; ISBN 0-9939074-0-1.

- Friedman, Y. L’ordine complicato. Come costruire un’immagine, 1st ed.; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italia, 2011; ISBN 88-7462-340-2.

References and Note

- Carroll, S.B. Infinite Forme Bellissime. La Nuova Scienza Dell’evo-Devo, 1st ed.; Codice Edizioni: Torino, Italia, 2006; ISBN 88-7578-037-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bodei, R. Oggetti e cose. In La Vita Delle Cose, 1st ed.; Laterza: Bari, Italia, 2009; p. 23. ISBN 88-420-8998-8. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, S. Dichiarazione Degli Obblighi Verso L’Essere Umano, 1st ed.; Castelvecchi: Roma, Italia, 2013; p. 30. ISBN 88-6826-012-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, S. L’eroismo della visione. In Sulla Fotografia. Realtà e Immagine Nella Nostra Società, 2nd ed.; Einaudi: Torino, Italia, 1992; p. 87. ISBN 88-06-12973-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, S. Quando la Gente Scoprì, e non le ci Volle Molto, che Nessuno Fotografa Nello Stesso Modo una Stessa Cosa, L’ipotesi che le Macchine Fornissero Un’immagine Impersonale e Oggettiva Dovette Cedere al Fatto che le Fotografie Non Attestano Soltanto ciò che c’è, ma ciò che un Individuo ci Vede, Che Non Sono Soltanto un Documento, ma una Valutazione del Mondo. In Sulla Fotografia. Realtà e Immagine Nella Nostra Società, 2nd ed.; Einaudi: Torino, Italia, 1992; pp. 77–78. ISBN 88-06-12973-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bibo, D. Libri illustrati per bambini, mercato internazionale e vendita dei diritti all’estero. In L’Editoria Illustrata è Viva e Funziona Ma Ha Nuove Regole; “Illustratore italiano”; 2017. Nr. 5; MOM: Gussago (BS), Italia, 2017; p. 39. ISSN 2499-2348. [Google Scholar]

- Ku-Ku! Reading Pictures from Birth is an independent reading education project which I have dedicated myself to continuously since 2012. So far, it has taken place in my home studio (with mothers and fathers) and in private and public spaces (with educators; in bookshops, cultural associations and nursery schools). One of the aims is to observe and experience in the field what provokes the reading of illustrated books during the early months of life. Adults, in this type of situation, are urged to discover that reading pictures is different from reading a story aloud; children are urged to read by themselves.

- Available online: https://graffica.info/isidro-ferrer-y-grafica-futura-disenan-el-dossier-para-la-presentacion-de-la-candidatura-de-madrid-2020/ (accessed on 8 January 2013).

- Nussbaum, M.C. Non per Profitto. Perché Le Democrazie Hanno Bisogno Della Cultura Umanistica, 1st ed.; Società Editrice Il Mulino: Bologna, Italia, 2011; ISBN 88-15-25304-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sfar, J. Se Dio Esiste. Quaderni Parigini. Gennaio—Novembre 2015, 1st ed.; Rizzoli-Lizard: Milano, Italia, 2016; p. 28. ISBN 88-17-08487-1. [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli, G. Il Fondamento Dell’Istruzione Artistica è Insegnare a Vedere. Available online: www.doppiozero.com (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- Munari, B. Guardiamoci Negli Occhi, 1st ed.; Edizioni, Corraini: Mantova, Italia, 2003; ISB88-87942-41-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik, A. Cosa si prova a essere bambini? Coscienza e attenzione. In Il Bambino Filosofo. Come i Bambini ci Insegnano a Dire La Verità, Amare e Capire Il Senso Della Vita, 1st ed.; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italia, 2010; ISBN 88-339-2059-7. [Google Scholar]

- Munari, B. Libro Illeggibile MN 1, 8th ed.; Edizioni Corraini: Mantova, Italia, 2017; ISBN 978-88-86250-15-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, J. Circulo o Cuadro, 1st ed.; Petra Ediciones: México, 2006; ISBN 968-6445-60-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pittau, F.; Gervais, B. Primavera Estate Autunno Inverno, 1st ed.; Topipittori: Milano, Italia, 2011; ISBN 88-89210-70-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ashbé, J. A Più Tardi! 1st ed.; Babalibri: Milano, Italia, 2007; ISBN 88-8362-161-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ponti, C. L’Album D’Adele, 1st ed.; Éditions Gallimard: Paris, France, 1986; ISBN 2-07-056297-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet, J. Presque Tout, 1st ed.; Éditions Du Seuil: Paris, France, 2004; ISBN 2-02-058252-0. [Google Scholar]

- Berner, R.S. Herbst-Wimmelbuch, 12th ed.; Gerstenberg: Hildesheim, Deutschland, 2011; ISBN 38-36951-01-2. [Google Scholar]

- Frereau, C. Un An, L’été, 1st ed.; Éditions MeMo: Paris, France, 2012; ISBN 2-35289-058-4. [Google Scholar]

- Oxenbury, H. Friends, 10th ed.; Walker Books: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 1-4063-4011-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mari, I. Mangia Che Ti Mangio, 2nd ed.; Babalibri: Milano, Italia, 2007; ISBN 88-8362-221-2. [Google Scholar]

- Abbatiello, A. Facce, 1st ed.; Topipittori: Milano, Italia, 2013; ISBN 88-8921-098-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, K. Nakawaki, H. Aspettami! 1st ed.; Babalibri: Milano, Italia, 2016; ISBN 9788883623745. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, L.; Vanetti, G. Il gufo... e gli altri, 1st ed.; La Coccinella editrice: Varese, Italia, 1979; ISBN 88-7703-091-7. [Google Scholar]

- Munari, B. Toc toc. Chi è? Apri la porta, 1st ed.; Edizioni Corraini: Mantova, Italia, 2003; ISBN 88-87942-36-6. [Google Scholar]

- Babalibri, Edizioni Corraini, Topipittori, Fatatrac, Franco Cosimo Panini, Emme Edizioni.

- Éditions Thierry Magnier, Greenwillow Books, One Stroke, La Joie de Lire, Les Grandes Personnes, Fukuinkan.

- Félix, L. Prendi e scopri, 1st ed.; Fatatrac-Edizioni del Borgo: Casalecchio di Reno, Italia, 2015; ISBN 88-8222-378-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pacovska, K. Alphabet, 1st ed.; Ravensburger Buchverlag: Ravensburg, Deutschland, 1996; ISBN 34-7333-367-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hoban, T. Look book, 1st ed.; Greenwillow Books: New York, USA, 1997; ISBN 06-8814-971-0. [Google Scholar]

- Komagata, K. Little Eyes, voll. 1-10. One Stroke: Japan, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Berner, R. S. Einfach alles! 1st ed.; Klett Kinderbuch: Leipzig, Deutschland, 2009; ISBN 3-95470-000-4. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Trimardeau, C. Hello tomato, 1st ed.; Éditions du livre: Paris, Francia, 2016; ISBN 979-10-90475-17-5. [Google Scholar]

- Munari, B. I prelibri, 2nd ed.; Edizioni Corraini: Mantova, Italia, 2015; ISBN 88-87942-66-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, J. Coloresy sabores, 1st ed.; Petra Ediciones: México, 2007; ISBN 96-8644-582-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tullet, H. Il gioco di “Andiamo!”, 1st ed.; Phaidon: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 0-7148-6182-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tullet, H. Jeu de hasard, 1st ed.; Éditions du Panama: Paris, France, 2007; ISBN 27-5570-254-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gurowska, M. Couleurs colours, 1st ed.; éditions MeMo: Paris, France, 2008; ISBN 2-35289-033-1. [Google Scholar]

- Komagata, K. First Look. Beginning for Babies; «Little Eyes», vol. 1; One Stroke: Japan, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hoban, T. Black on White, 1st ed.; HarperCollins: New York, USA, 1993; ISBN 0-688-11918-8. [Google Scholar]

- Marceau, F.; Jolivet, J. Panorama. A foldout book, 1st ed.; Abrams Books: New York, USA, 2009; ISBN 0-810-98332-8. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, K. Show me the inside of your hands, 1st ed.; Fukuinkan: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; ISBN 491003803030500390. [Google Scholar]

- Bruna, D. My vest is white, 1st ed.; Tate Publishing: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 1-84976-075-1. [Google Scholar]

- Couprie, K.; Louchard, A. Tout un monde, 1st ed.; Éditions Thierry Magnier: Paris, France, 2008; ISBN 28-4420-063-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bravi, S. L’uccellino fa..., 1st ed.; Babalibri: Milano, Italia, 2005; ISBN 88-8362-122-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hoban, T. Shapes, Shapes, Shapes, 1st ed.; Greenwillow Books: New York, USA, 1986; ISBN 0-688-05832-6. [Google Scholar]

- Humbert, N. Veau, Vache, Cochon..., 1st ed.; La Joie de Lire: Genève, Swiss, 2012; ISBN 2-88908-135-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dé, C. Compte sur tes doigts, 1st ed.; Les Grandes Personnes: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 2-36193-462-0. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).