On 17 November 2016, at the Milan office of Banca Prossima, the Umbria Region was awarded the

grandesignEtico International Award: an award that is promoted biyearly by the

Plana Cultural Association to promote Italian design of excellence and qualified by a board of absolute prestige. The news raised a great media echo, because for the first time, instead of being a private company or a professional studio, recognition was assigned to a public institution that distinguished itself for the “commitment in launching productive assets and defending ‘artisan know-how’, qualifying this region as the first in Italy and in Europe to embark on an ethical and social path.” A well-founded reason because, while the rest of Italy is engaged in regional enhancement processes that tend to converge in the practice of territorial marketing, the Umbria Region, confirming its pioneering vocation in communication design, chose the most difficult but most innovative route of territorial branding [

1], choosing the design of strategic communication. This represents the goal of a path that began almost unconsciously in Perugia in December 1971 when the Regional Council Presidency proclaimed a public competition for the creation of the institutional coat of arms opened to “all Italian citizens, wherever they reside, even those who emigrated abroad” (sealed in 1973 with the adoption of the coat of arms and of the banner with the stylized outline of the three Ceri di Gubbio,

Figure 1a), and that consciously arrived in Spoleto in July 2016, when the culture of design found its space in the official programme of the

59esimo Festival dei 2 Mondi (59th Festival of the 2 Worlds) (with the blessing of a true “guru” of the industry like Gilda Bojardi [

2]). In the middle, a forty-five year long journey towards contemporaneity, marked by the important restyling stages of the coordinated image (sealed by the adoption, in 2004, of the

Bollo Rosso (or Red Seal,

Figure 1b) [

3] (pp. 12–13)), which underwent a rapid acceleration in recent years, first with the involvement of internationally renowned professionals such as Oliviero Toscani, Michele De Lucchi and Steve McCurry and then with its continuous presence in exclusive events such as the

Fuorisalone 2013, the

Expo 2015 and the exhibition,

Interni Open Borders [

4].

On the other hand, the “green and medieval” image that Umbria has given for a long time is now outdated. If nothing else, because it is offhanded as it is recent. It’s an offhanded image because the DNA of the Umbrian historical centres is not only medieval, it is a spectacular layout where all the periods coexist synergistically and where every single stone, every brick, every single capital has not been disposed of in a landfill in the outskirts, but was recovered and reused to build on the already built-up area: starting with “Maschia Peroscia” [

5] (p. 1). But the “green and medieval” image is also recent, because the claim “Italy has a green heart: Umbria”, while combining the title of a book published by Carlo Faina in 1925 (

Umbria verde [

6]) with the slogan “Umbria, cuore d’Italia” (Umbria, heart of Italy) conveyed by the book of regional culture used in elementary schools during the fascist period [

7] (p. 4) was coined less than fifty years ago, during the summer of 1970 in the wake of the Umbria Region [

8] (pp. 61–62).

Yet, even though it is exceptionally effective from a communicative point of view, the “green and medieval” image has never expressed the regional identity thoroughly. Just as it was implicitly acknowledged by the Umbria Region itself with the adoption in 1973 of a coat of arms marked by the graphic revisitation of the Ceri di Gubbio silhouette: three wooden architectures that enliven a folk party far from green, because rooted in the urban culture of the “city of stone”, and with different shapes other than medieval ones, because composed as per strict Renaissance proportional standards [

9] (pp. 105–106). Above all, however, the “green and medieval” image of Umbria is artificial, because it embodies the outcome of a precise cultural programme that, on close inspection, established its roots in 1819 when the Accademia di Belle Arti of Perugia, having given credit to a report by Antonio Canova, appointed Tommaso Minardi, painter from Faenza, as director. Minardi, amazed by the great Umbrian art of the middle ages, denied the Neoclassical formation received in Rome and embraced the clear and essential figurative language of Italian primitive painters (from Cimabue to the first Raffaello), giving rise to an impetuous medievalist swerve (

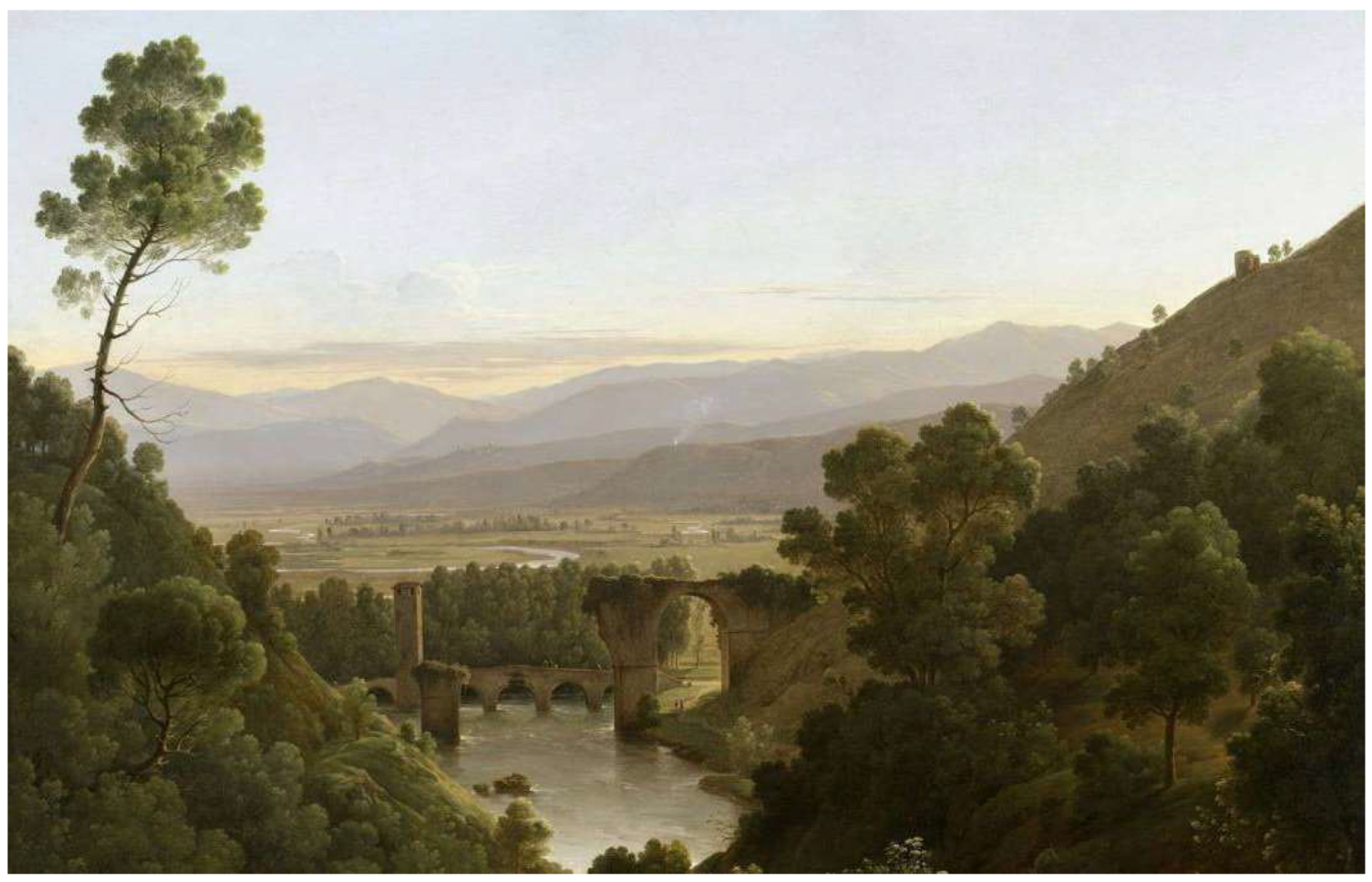

Figure 2). But most of all, Minardi attracted an intense coterie of northern European artists in Umbria (mostly Nazarenes and Purists) who, by contaminating the naturalism of the views of plenaryist painters with artificial elements selected tendentially within the local historical repertoire, chose the natural environment/Medieval art mix to artistic creed, promoting the affirmation of “green and medieval” Umbria beyond local boundaries (

Figure 3).

The positive repercussions of the cultural project launched by Tommaso Minardi (fostered by Giovanni Sanguinetti in the classrooms of the Academy and conveyed by Marianna Bacinetti in the social gatherings of Palazzo Florenzi) did not delay in appearing: so much that, at the end of his mandate, Umbria was more than just a destination of religious pilgrimages, it was also a destination for grand artistic tours that broke the monotony of a cultural life otherwise closed on itself. It was no coincidence that, between 1822 and 1825, the register of academic excellences of the Accademia di Belle Arti of Perugia, in addition to the renowned name of the painter, Johann Friedrich Overbeck, was characterized by the names of many other renowned northern European artists such as the engraver, Samuel Amsler, coiner Johann Josef Daniel Böhm, architect Carl Friedrich von Wiebeking, sculptor Konrad Eberhard and painters Carl Adolf Senff, Joseph Carl Stieler and Peter von Cornelius [

10] (pp. 89–90). The evidences of the renewed interest of northern European travellers for Umbria are numerous. But, above all, the statement by the German art historian, Karl Friedrich von Rumohr, stands out. He disputed with the indifference brandished towards the Sacred Convent by Johann Wolfgang Goethe in the

Italienische Reise, and claimed the charm of the luminary climax raised by François-Marius Granet in

Intérieur de la basilique basse de Saint-François, à Assise [

11] (pp. 193–194). Just like the attestations of British landscapist, William Blake Richmond stand out. While dabbling as a writer he depicted a poignant poetical description of the Umbrian valley [

12] (p. 176).

All the great artists and all the great architects working at the time in Umbria aligned themselves with the new cultural project (they could have done differently, as they all attended the Accademia) and began to build a landscape consistent with the new ideological concept, portraying the cities within the lush naturalistic contexts and designing buildings according to Medieval style standards. This romantic attitude led Umbria up to the post-Risorgimento age, when the image of “green and medieval” Umbria got a further boost. As illustrated by the allegories created by Domenico Bruschi in the Council Hall of the Palazzo del Governo in Perugia, which shows a common identity based on the polygonization of the historical individualities of each single city and on whose background an unspoiled nature reigns supreme, that imprints on the Region the poetic brand consecrated a few years later by Giosuè Carducci in the ode,

Alle fonti del Clitumno [

13], inspired by a stroll along the artificial park desired by Paolo Campello della Spina to recreate the idyllic climax of the landscape described by Pliny the Younger.

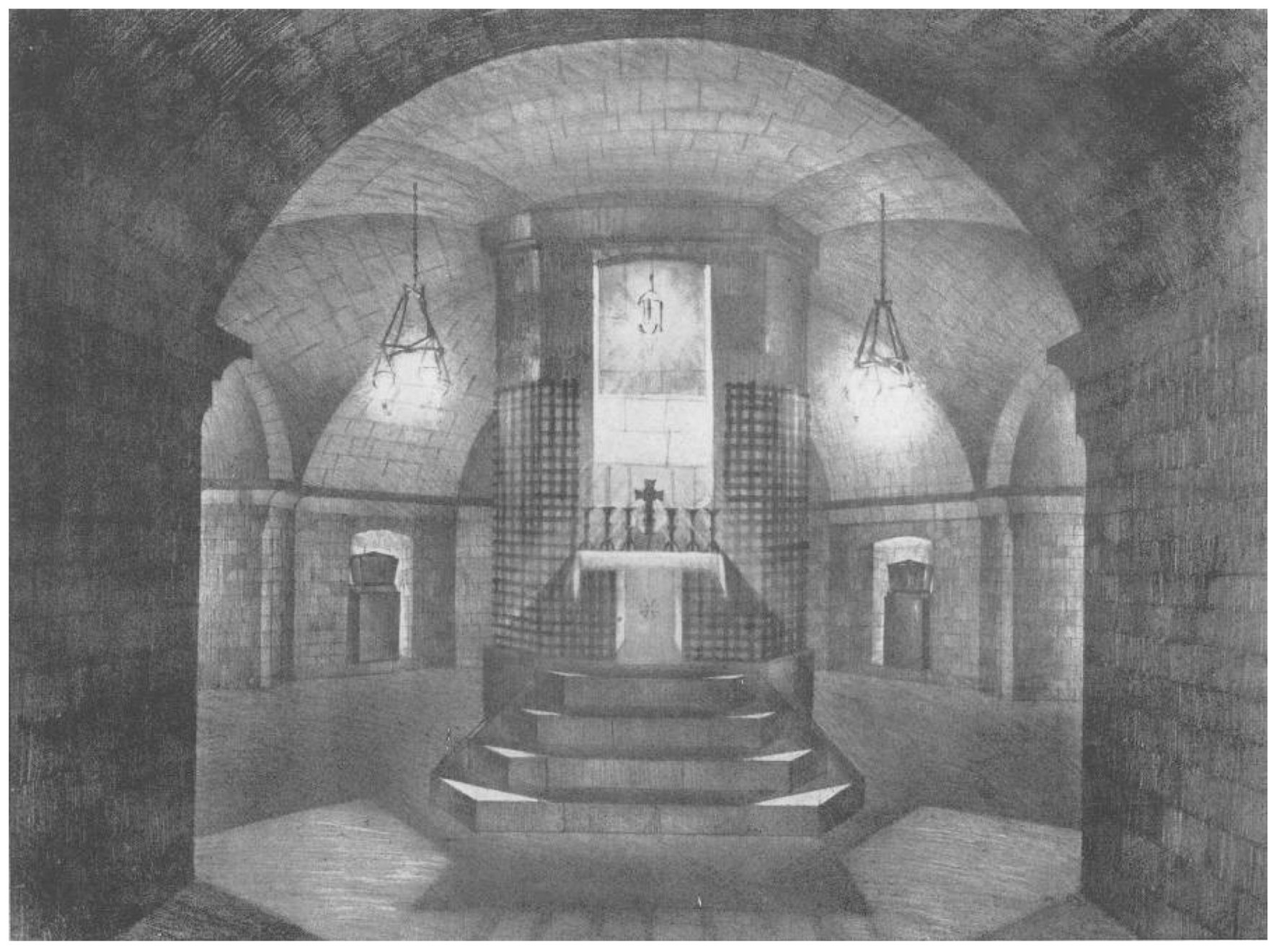

The image of the “green and medieval” Umbria launched by the commissioners following the unification and propagandized by Carducci obtained a great success. So much so that it was not only adopted, but it was even taken to extremes by the fascist hierarchs, which reduced the territorial polygonization to a triangulation where Assisi was reduced to a whole and all the other cities conformed to Perugia or Terni, according to a representation of the bicultural region, ancient and modern at the same time. This had a profound impact on urban policy and, consequently, on architectural translations: in Assisi and Perugia (as well as in the cities associated with them: Gubbio, Narni, Spoleto) tended to restore or to build in an eclectic style, disseminating historical centres with false neo-medieval settings, while in Terni (and in the towns associated with it: Bastia, Città di Castello, Foligno) tended to build in a modern style, colonizing the suburbs with algid rationalist condos [

14] (p. 9). This was how “Perugia-città della cultura” (Perugia-city of culture), “Terni-città dell’industria” (Terni-city of industry) and “Assisi-città della religione” (Assisi-city of religion) became inseparable binomials that evoked many foreign examples: Perugia like Oxford, Terni like Manchester and, more than anything, Assisi like Bethlehem. It was no coincidence that in the same years when Vittorio Grassi drew an advertising poster in which the Sacred Convent, framed by the metaphysical profile of an ogival arch, laid on an unspoiled agricultural landscape, Ugo Tarchi conceived the restyling of the crypt that holds the tomb of San Francesco as a medieval setting, removing the neoclassic algus stuccoes lavished on by Pasquale Belli and introducing rough calcareous limestone caves from the slopes of Mount Subasio. This obviously raised bitter critiques [

15]. On the other hand the cultural delay that, during the post-war reconstruction, marked Umbrian architecture with respect to the national disciplinary debate, called into question the structural limits in the image of “green and medieval” Umbria sealed by the poster of Vittorio Grassi and by the crypt of Ugo Tarchi (

Figure 4). Because the neo-Gothic abundance of the Santa Rita Basilica of Spirito Maria Chiappetta at Cascia looks awkward compared to the neo-realistic climax of San Vincenzo’s church of Ludovico Quaroni in Matera, as well as the neo-Romanesque historicism of the Mausoleum of the 40 Martyrs of Pietro Frenguelli in Gubbio appears dull when compared to the anti-rhetorical minimalism of the Mausoleum of the Fosse Ardeatine by Mario Fiorentino in Rome [

16] (pp. XIII–XIV).

However, beginning in the second half of the 1950s, Umbria betrayed the first symptoms of intolerance for a cliché that began to betray the guidelines of its being and, apart from bursting into unusual productive contexts such as fashion and aerospace, it stood out as a workshop dedicated to experiencing pioneering forms of regeneration of its historical centres. The undisputed creator of this metamorphosis was Giovanni Astengo: designer of the General Regulatory Plan of Assisi, the inspiration behind the

Carta di Gubbio (Gubbio Charter) and founder of the

Associazione Nazionale Centri Storico-Artistici (National Association of Historical-Artistic Centres) [

17] (pp. 55–56). Initially, the new regeneration forms of historic centres were limited to the iconic exploitation of public spaces during major cultural events: from the exhibition

Sculture nella Città (Sculptures in the City,

Figure 5) [

18] (p. 177), set up in Spoleto within the

V Festival dei Due Mondi (5th Festival of Two Worlds), at the first travelling editions of

Umbria Jazz [

19] (pp. 19–20), located in the most symbolic places of Castiglione del Lago, Gubbio, Orvieto, Perugia and Piediluco.

But then, over time, the new regeneration forms of historic centres (and of the architectural heritage in general) became more and more concrete and, in the passing of a few years, became exemplary models, studied and emulated at an international level: from the transformation into museums of the former tobacco drying rooms at Città di Castello [

20] (p. 40) to the creation of the mechanical lift in the Rocca Paolina in Perugia [

21] (p. 82). Up until the exploit of the post-seismic reconstruction of Foligno’s historic centre. Which sealed the ability of Umbria to relate to the existing elements without “obsequious inferiority” precisely because it had not been qualified by the ordinarity of philological restorations, but by the excellence of inventive restorations, which include the two locations of the Centro Italiano Arte Contemporanea (Italian Centre for Contemporary Art), designed by Giancarlo Partenzi and Guendalina Salimei [

22] (p. 132). Nonetheless, Umbria continued to be identified with the (now former) integrity of its historic centres and with the (now former) amenity of its green hills or with the “green and medieval” image disclosed in movie theatres by the languid sequences of the film

Fratello Sole,

Sorella Luna by Franco Zeffirelli (

Figure 6) and in the newsstands with the wise words of Cesare Brandi together with the clear photographs of Mario De Biasi published in the insert

Cara Italia: Umbria of the magazine

Epoca [

23] (p. 1).

But things change, and in recent years the abuse of the “green and medieval” stereotype also led to negative social and economic repercussions, stifling the visionary impulses of an entrepreneurial class that, for too long, continued to cling onto the certainties of extemporaneous tourism tied to an image that is now dated and worn-out [

24] (p. 235). Certainly the image of “green and medieval” Umbria still attracts the attention of retired intellectuals, but it certainly does not attract more creative younger minds, polluting the rural landscape with the regurgitation of an incurable Mulino Bianco (or one big happy family) syndrome and encouraging the transformation of abandoned towns into dull wellness resorts rather than lively workshops of knowledge. Hence the reasons why the Umbria Region, two centuries after the viewpoints of Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot and François-Marius Granet, again reiterated the communication of artists and writers: the Oliviero Toscani concept for the institutional stand at

Vinitaly 2009 (who claimed the need for frugality and spiritual dimension), Michele De Lucchi’s designs for the collection

Maioliche Deruta 2012 [

25] (which highlighted the importance of renewing the repertoire of artistic handicrafts) and Steve McCurry’s photographs for the campaign

Sensational Umbria [

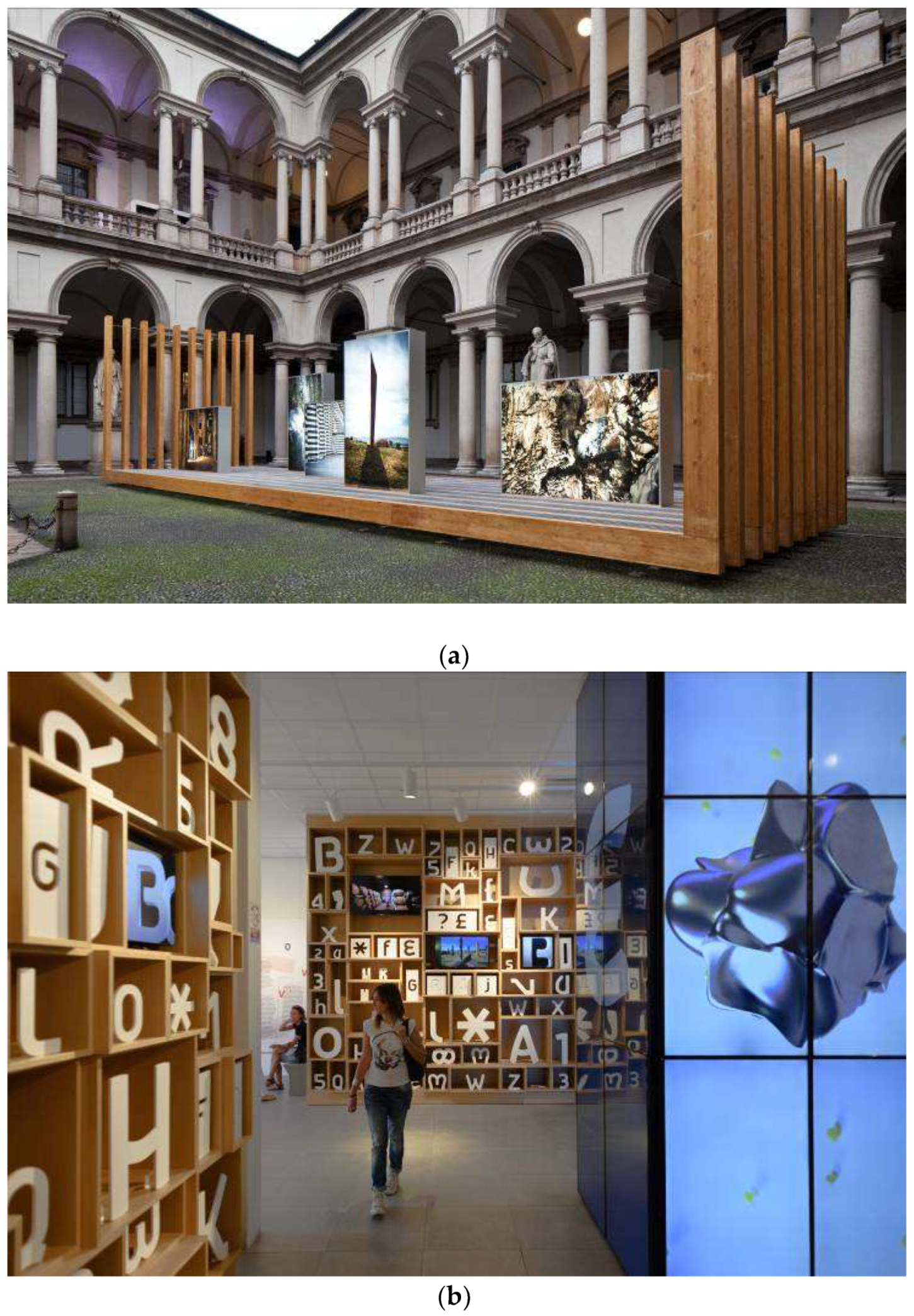

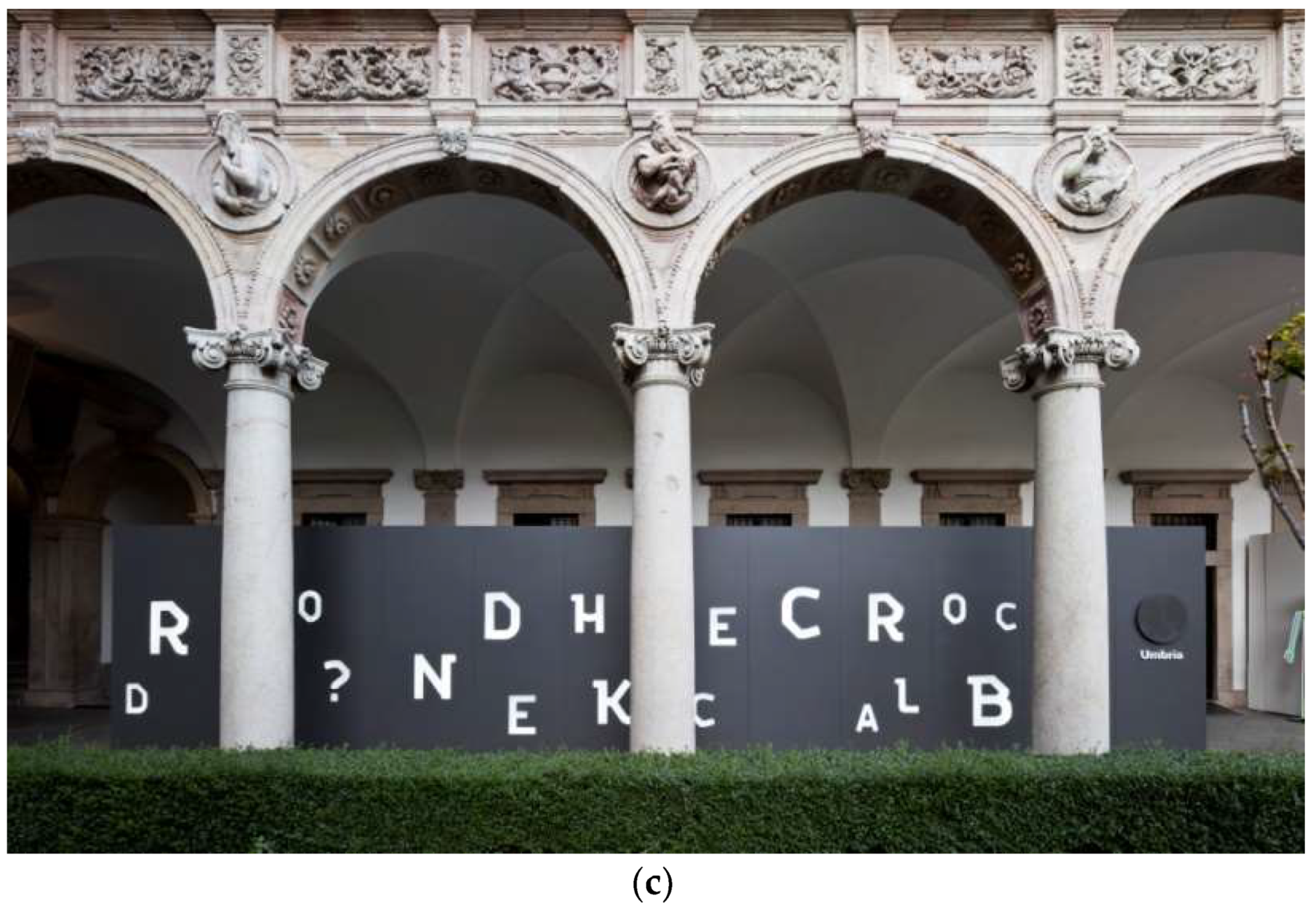

26] (who opted for geographic identity). But even less accidental, two centuries after the decisive role played by Tommaso Minardi and Giovanni Sanguinetti in the academic classrooms, the Umbria Region again relied on the local higher education, combining the skills of designers and scholars of the Università degli Studi with the skills of the artists and designers of the Accademia di Belle Arti “Pietro Vannucci” to then make them synergistically converge into a cultural programme that developed over a five-year period in the symbol places of Milan (in 2013 in the Napoleonic courtyard of the Brera palace with the exhibition pavilion

Teatro delle immagini (

Figure 7a) [

4] (pp. 45–68), in 2015 in the rotating area of the Italia Pavilion with the exhibition

Convivium 2.0 (

Figure 7b) [

4] (p. 69–96), in 2016 and 2017 in the central courtyard of Ca’ Granda, first with the exhibition

Scorched or Blackened (

Figure 7c) [

4] (pp. 97–126) and then with the travelling exhibition,

Fabric-Action [

27]). A five-year period that reestablished a deep awareness: the Umbria of the third millennium will no longer be able to free itself from the alternating image of “green and medieval” with a new image. Which however is yet to be invented, but that perhaps, by combining a subtle aphorism by Philippe Daverio (“a land lacking in people but rich with time” [

1] (p. 163)) with a sharp notation by Michele De Lucchi (“the absolute greatest value in Umbria is that of authenticity” [

28] (p. 11)), could embody the claim

Locus Umbria, communicating the unique and exclusive identity of an authentically contemporary workshop-region, measuring itself with the boundaries of an experiential culture whereby knowledge and know how foster one another. Albeit without shedding tears over the last two hundred years of latent romanticism that is always a sign of continuity and everyday life of beauty, therefore the beauty of life that rotates around the objects is more important than the beauty of the objects itself.