Aesthetics and Poetics of the Image in Japanese Culture

Unlike Western literature whose compositional and syntactic structure always predominates, in accordance with a tradition that has its roots in ancient rhetoric, Japanese literature, from its origins, is not based on a compositional structure that is primarily logical, formal, and linear. The novels of Yasunari Kawabata (1899–1972) (See

Figure 1) illustrate this point in that there is no well-constructed plot, but rather a series of situations that emerge directly from images, in a sort of concrete visual thought that overshadows the storyline. The vehicle is an ideographic narrative structure, as opposed to the narrative syntax of an alphabetic language. The Japanese and Chinese, in fact, think in images and give visual form to ideas or things through the sinograph; the symbolic and semantic lexicon of ideograms indicates objects and ideas by representing them in images. Logical and syntactic structure is abolished even in the haiku, which consists of three unrelated images: optical fragments. There is no relationship among the parts; instead, we have the juxtaposition of three moments in which the description of the countryside predominates. In Chinese painting too the images prevail over space in that there is no single perspective, but rather multiple angles of observation generated by the succession of images. The eye perceives these in a process that is temporal as well. The fusion of space and time in a single dimension is perhaps the most profound feature of all the art of the Far East.

Appearing to be inspired directly by the haiku, Kawabata’s Palm-of-the-Hand Stories are minimalist tales, a juxtaposition of optical fragments that amplify the beauty of the real world. Such short works were a lifelong interest of the author, perhaps tied to a need for succinctness, as is the case in Japanese poetry.

The preference for brevity is a feature of several of Kawabata’s work, especially

Yukiguni [Snow Country], his masterpiece. The novel is known for its elliptical style. According to Giorgio Amitrano, to whom I am indebted for many of the thoughts contained in this text, thoughts derived from his university lectures,

Snow Country is a series of impressions. The writer chose to omit all specific points of reference in order to maintain an evocative, rather than an assertive, register. This is the author’s poetics, that is to say, the decision to suggest rather than explain. A large portion of the book’s interest lies in this capacity to evoke. The plot is thin and lacks those details that give the story a true beginning and conclusion. The emotional engagement of the protagonist Shimamura is relative; it is as though he were observing from the outside, always maintaining a certain detachment, without really participating in the events. Some images create a very evocative atmosphere. Shimamura’s passing through a tunnel symbolizes his entry into another world, a dimension different from that of his daily existence. The mirror, which is mentioned often, conveys the detachment of the observer, who is always aloof in relation to the world around him. “Like sight, writing is done only in the presence of a distance that depicts what it withdraws. This is to say that in this literature the world reveals itself only indirectly, in the reflected image of the mirror, a diaphragm between the eye and the real world. […] Only a passionate form of writing, but one detached from life and its process of becoming, has the privilege of illuminating reality” [

1] (p. 12). Kawabata is masterful in creating atmospheres where feelings are more suggested than described directly, and he does not provide a consistent evolution of facts; the story opens with a completed action and from that moment shifts to the past and then back again to the present in circular fashion.

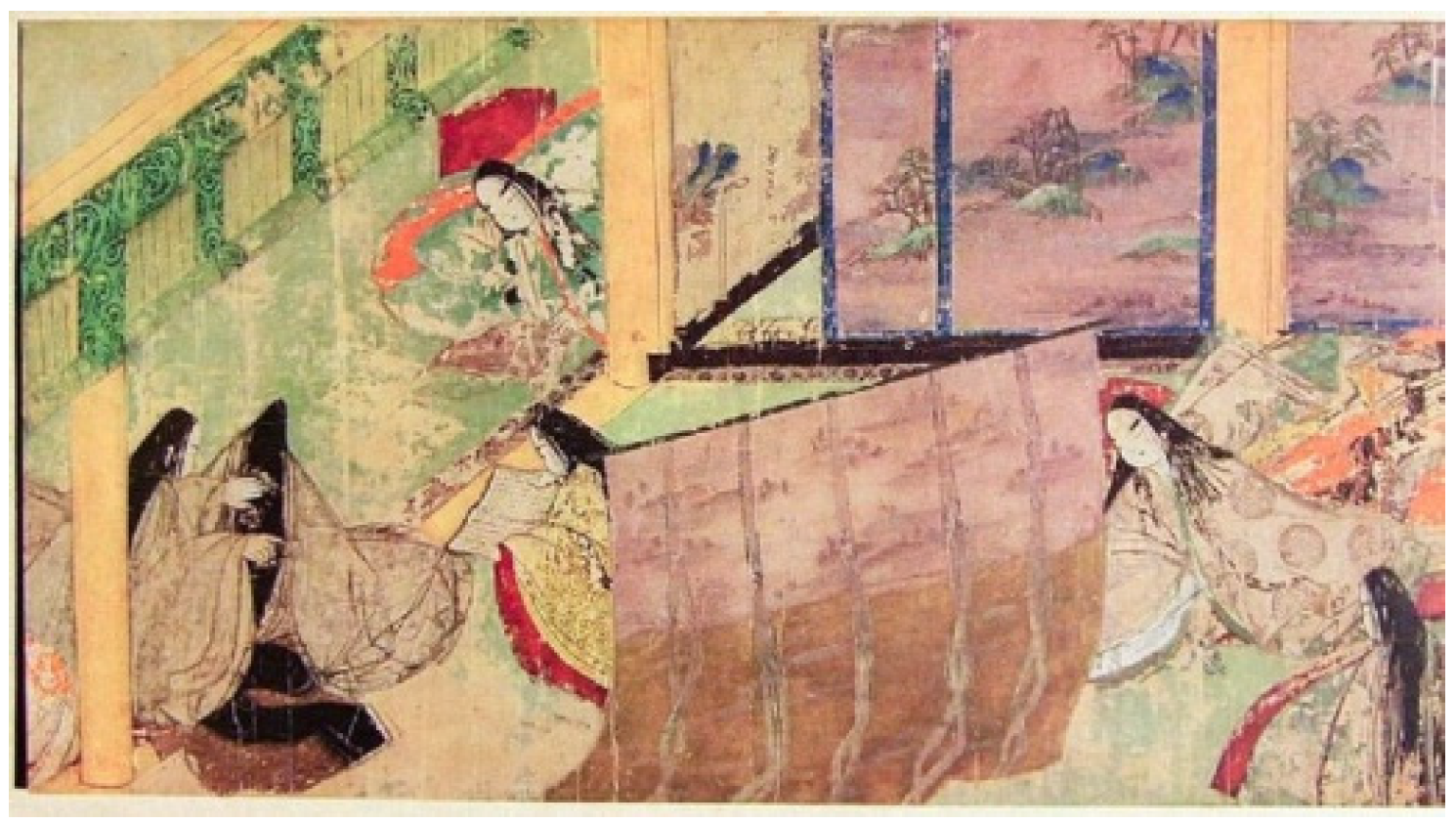

Snow Country comprises a series of visions evoked poetically that communicate certain impressions. Kawabata’s quasi cinematic mode of writing with images or painting with written words recalls the

emakimono or “picture scrolls”, traditional illustrated narratives that flourished during the Heian and Kamakura periods: a series of horizontal images and text painted on silk or paper that the reader experiences gradually as he or she unrolls the scroll from right to left. In

Genji monogatari emaki [The tale of Genji scroll], one of the most famous Japanese works of art from the 12th century, the images illustrating the story of Genji have the appearance of a film strip, unfolding within an almost oneiric space. (See

Figure 2)

Shimamura, an intellectual, an aesthete, and a critic of Western ballet, which he has never seen nor ever will see, is a romantic dreamer in search of an authentic sense of wholeness. The author does not provide the details of the story and does not dwell on the psychology of the character, but he does succeed in communicating a great deal through sensations: the object that the protagonist looks at becomes a symbol of his own condition. The characters remain mysterious, but the sensorial experience is emphasized throughout the book. Kawabata is one of the founders of the Shinkankakuha (

ha or school in the sense of “artistic and literary movement”, and

kankaku or sensation). This would be the New Sensations School associated with modernism, a new way of understanding literature. (In the context of the modernist project of Shinkankakuha, Kawabata writes a work adapted for an experimental film called

A Page of Madness, directed by Teinosuke Kinugasa, in which images assume a particular power. The film can be read as a short story for intents and purposes. It is possible to view stills of the film at the following site:

https://www.google.it/search?q=a+page+of+madness+de+teinosuke+kinugasa&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwizt4SB8ZzWAhVLshQKHYV_ALIQ_AUICigB&biw=1024&bih=673#imgrc=Z4oksynY0wS45M:&spf=1505124912873) Sensations are transmitted by the senses; they are a mode of registering internally something that comes from the external world. The objective of this school was to underscore the importance of sense impressions. Kawabata participated actively and, once the initial enthusiasm faded, he followed his own path, as did the other exponents of the school. The effects of this intense interest in sense impressions can be seen in Snow country. Impressions related to the senses of touch, hearing, and sight, abound in the novel. The author’s hypersensitivity to this feature is obvious. For example, he returns frequently to the sound of Yōko’s voice: “The voice was so beautiful that it melted your heart. Its sharpness seemed to reverberate across the night snow” [

2] (p. 4).

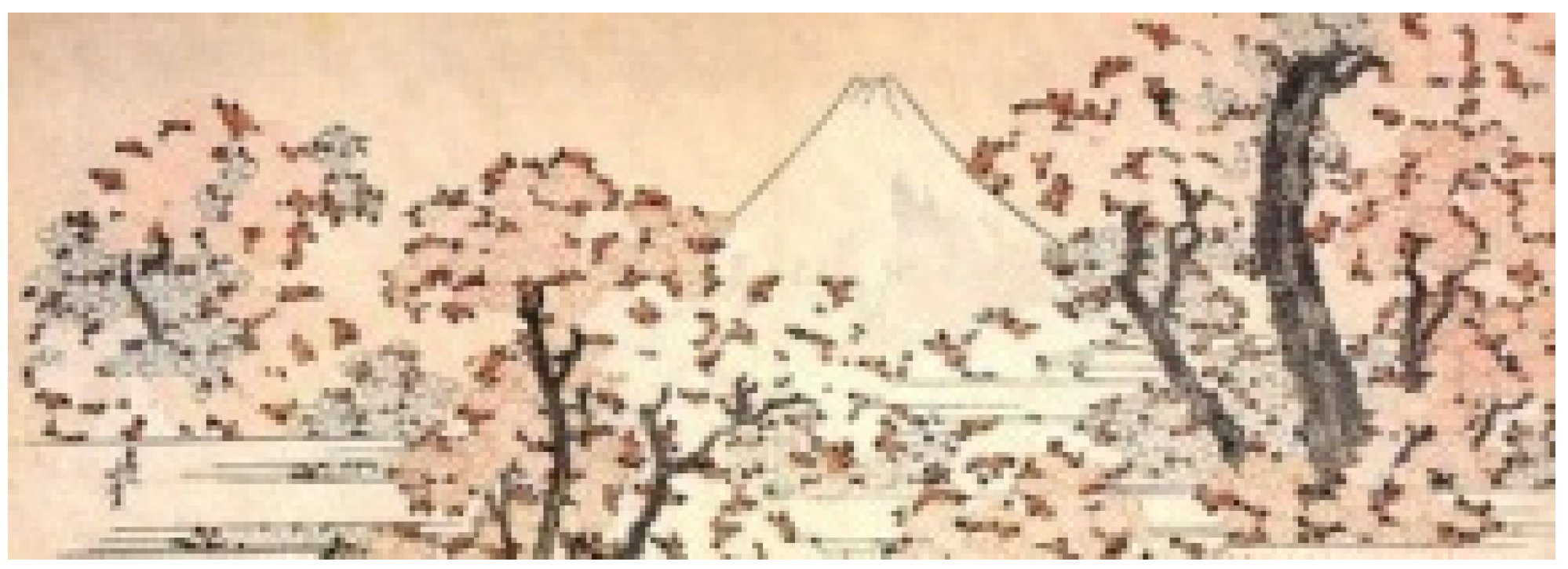

At the start of the novel, a train emerges from a long tunnel against a snow-covered landscape: “Having come out of the long tunnel under the border, we were already in snow country. The dark night began to turn to white” [

2] (p. 3). With this incipit, we enter physically into the novel; we live the moment of passage as we cross from the darkness of the tunnel to the white of a place covered in snow. Because it is evening, the transition is not blinding; however, it still has a glow. This is an extraordinarily effective opening as Shimamura looks out of the train window and sees, superimposed on the evening backdrop, the face of Yōko, the girl seated in front of him, and when the light shines in her eyes, he experiences a deep aesthetic emotion: “If it is only through distance that we see the world, this is, however, due to the nostalgic desire of one who becomes truly aware of its beauty. Hence, Kawabata’s mirror mediates in two ways in that it withdraws the world from the actions of the subject while, at the same time, it filters that world through the profound emotion that distance evokes” [

1] (p. 21). (See

Figure 3)

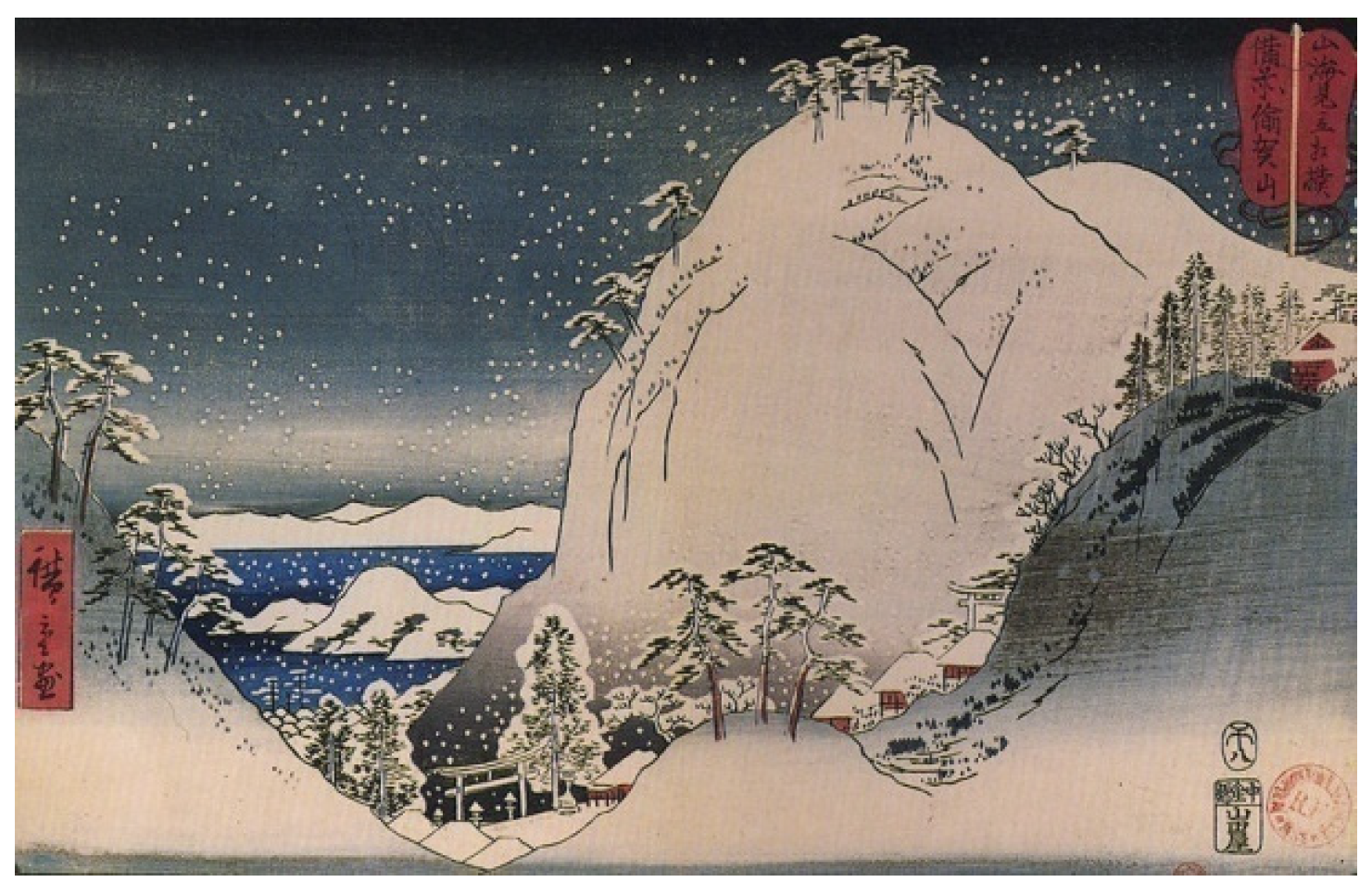

During the Edo period, literary critic Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801) studied the concept of

aware extensively and assigned to it the meaning of “feeling” (in modern Japanese

kanjō) (See Y. Ichihara de Rénoche [

3] (p. 102).) and identified it as fundamental feature of the Japanese aesthetic vision, as well as the main theme of the

Genji monogatari. Furthermore, he claimed that literature must have the function and value of communicating the

mono no aware and nothing more; this constitutes its greatness. The term

aware refers to a refined and intense sensibility with respect to the transitory nature of beauty. The term’s melancholy connotation stems from the feeling of impermanence, the Buddhist concept of

mujōkan, which is of central importance from the aesthetic and religious point of view even prior to the Heian period and becomes a dominant feature in the second half of that period, attaining its apogee in the succeeding Kamakura period with the spread of Buddhism into all forms of art and thought. It is precisely the “insubstantiality” of human reality and its transitory quality that amplifies the feeling that things inspire. The cherry blossom,

sakura, is not loved because it is more beautiful than other flowers, but because it blooms for a brief time, only a few days. The flower is destined to wilt and die; its beauty is as intense as it is ephemeral, fragile, and evanescent. In his essay “Japan, the Beautiful, and Myself”, the text of the acceptance speech he gave on the occasion of the conferral of the Nobel Prize on him in 1968, Kawabata identifies with limpid concision those aspects of the Japanese artistic tradition to which his works regularly make reference, at one point mentioning one of the stories from

Ise monogatari [The tales of Ise], which describes how the poet Ariwara no Yukihira arranged flowers as he awaited the arrival of some guests. Among those flowers was “an extraordinary branch of wisteria” more than a meter long. Here are Kawabata’s words describing this flower:

It is truly surprising to find a branch of wisteria of that length and it is doubtful that the author was telling the truth, and yet I see this wisteria blossom as the symbol of the whole culture of the Heian era. The wisteria is a very Japanese flower and has an entirely feminine grace; its clusters moving in the gentle breeze seem delicate, flexible, and of a humble beauty, and while they show themselves and hide among the greenery of early summer, they appear to inspire that intense feeling we experience for the things around us, a feeling known as

mono no aware. Certainly, that branch must have had an exceptional beauty. About one thousand years ago, after the culture of China’s Tang dynasty was completely assimilated, a splendid Heian culture was born in Japan and the principle of beauty was formulated; a surprising miracle similar to the blossoming of that “extraordinary branch of wisteria”. During that time the masterpieces of classical Japanese literature appeared […] thus, an aesthetic tradition was created, one that would not only influence the literature that came over the next eight hundred years or so, but in a sense dominate it [

4] (p. 1250). (See

Figure 4)

We discover a special emotion in the opening lines and in the epilogue of

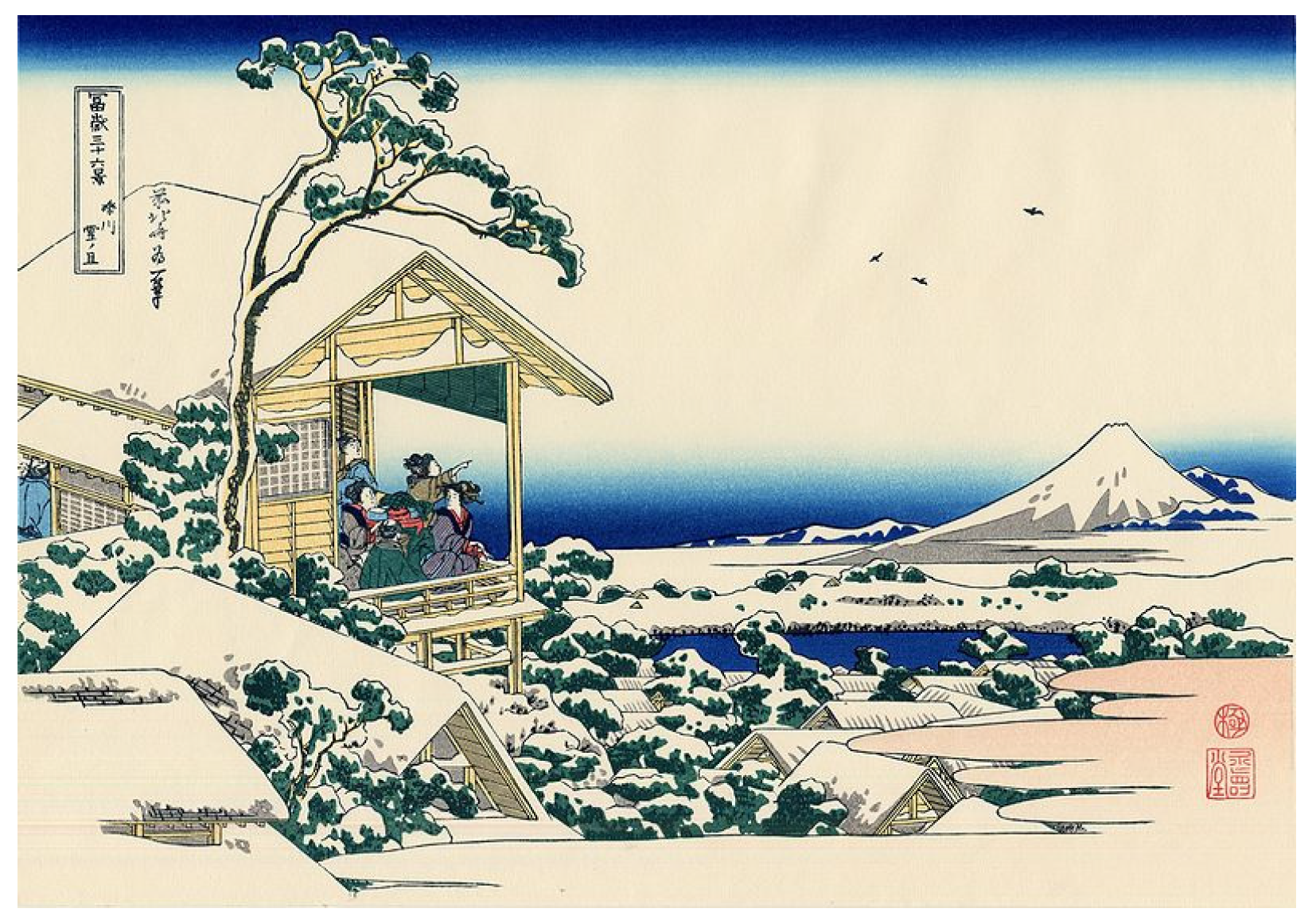

Snow Country. (See

Figure 5)

There is a great deal of poetry in this work, whereas the characters are rather flat. Early in the novel, the reader’s attention is concentrated on minute details that open up to an expanded and deeper scenario. On the train, the protagonist fumbles with his index finger, the site of tactile sensations, which preserves the impression or vivid memory of the woman he is about to meet, Komako. The sensation, in fact, seems to have a memory of its own, although the memory is fleeting. This detail then opens up into something of a chasm: he looks at his finger, brings it up to his face and then toward the train window. As he makes this gesture, an eye appears, a surreal and oneiric image. He almost lets out a scream, and then he realizes that his is a normal reflex. It is the eye of the girl sitting opposite him, Yōko. The window pane is transformed into a mirror, in a scene of great sophistication:

[…] suddenly at that moment a woman’s eye appeared clearly before him. He was so surprised that he almost let out a scream. But he was lost in his imagination and, when he came out of his trance, he realized that it was only the reflection of the woman seated across from him. Outside, night was falling and the lights in the train came on, transforming the window glass into a mirror. But the mirror, which was covered in mist, had remained hidden until the moment he ran his finger across it [

2] (p. 6).

[…] In the mirror, the evening landscape flowed by, such that the objects reflected and the reflecting surface moved like two superimposed images in a film. There was no relationship between characters and the background. However, the characters, made immaterial by the transparent surface, and the landscape, as it flowed indistinctly in the dim light, blended together to create a symbolic, ethereal world. In particular, when a light appeared in the mountains right in the middle of the girl’s face, Shimamura shook from the emotion caused by the ineffable beauty of the image before him [

2] (p. 7).

[…] The interior of the train was not well lit and the glass did not have the precision of a real mirror. Therefore, as a result of staring at it, Shimamura increasingly forgot that what he was looking at was merely a reflection, as within him the feeling grew that the girl was actually floating in the twilight landscape.

It was then that the light shone on her face. The image in the mirror was not vivid enough to erase the light that had appeared outside the window. Nor was the light strong enough to erase the image. Therefore, it passed through striking the girl’s face, but it did not manage to make it glow. It was a cold and distant light. When it struck the constricted pupil, that is to say, the moment when the pupil and the light interact, the girl’s eye became a phosphorescent insect of arcane beauty drifting on the waves of the dimness [

2] (p. 8).

Here we have an artistic effect. Shimamura is not an artist in the strict sense of the word; he is a scholar interested initially in traditional Japanese dance and later in Western ballet. He chooses an art form that he cannot enjoy in person. His is an attempted flight into the fantasy world of art in an effort to defer facing real life. He transforms what he sees and everything becomes an artistic, ecstatic vision for him. He enters a dream world in which he is perceives with the force of sensations and plays with them. When the train reaches its destination, he emerges from this state of unreality and wonders if something was supposed to happen between the eye and his finger, between Yōko and Komako, two perceptions joined together in his mind:

Without understanding why, Shimamura had the feeling that he could know, somewhere inside him, what there was and what could happen between the two women, the one whose memory was preserved in his finger and the one in whose eye he had seen a light shine. Was it perhaps because he had not completely emerged from his vision of that landscape in the mirror at twilight? And that darkness flowing behind the glass, he whispered to himself, was it a symbol of the passage of time? [

2] (p. 11). (See

Figure 6)

Yukiguni [Snow Country] is a work that seems to explore the desperate search for a beauty that always eludes you and never assumes concrete form. The natural world plays an important role in this quest, and it is only in this context that the events of the story acquire meaning. Nature is a projection of the state of mind of the characters, which are intertwined inseparably with the landscape. The author projects their psyche onto nature. For instance, when Komako removes the white make-up from her face in front of the mirror in Shimamura’s room, her milky skin stands out against the snowy mountains and the red of her cheeks creates a light in the center of the image. In the mirror, reality gives way to a dream world where nature and the girl’s whiteness are one. This is an evocative, romantic, and poetic register. Komako is a blend of vitality and melancholy that inspires Shimamura’s quest to attain purification and, at the same time, his search for a vital force. In fact, Komako and the purity of the snow-covered mountains are always inseparably linked:

Shimamura looked at her and suddenly bowed his head. That blinding gleam in the mirror was the snow. And in the midst of all that whiteness her flaming cheeks stood out. It was an image of the purest, indescribable beauty.

The sun must have risen because now the snow gleamed even more brightly, as in a cold fire. Almost complementing the landscape, even her black hair, which stood out against the snowy backdrop, became more intense, turning into a brilliant violet haze [

2] (pp. 36–37).

We have a bold contrast in colors here with the white of the snow and Komako’s red cheeks; and she is endowed with warmth that suggests fire. Shimamura is attracted to both Komako and Yōko; it is a very intense attraction. On the day after her arrival, he recognizes the sound of Yōko’s voice, “a transparent voice, so beautiful that it was heart rending. He almost expected to hear its echo reverberate from somewhere” [

2] (p. 42). (See

Figure 7)

We also have these lines:

Yōko gave Shimamura a single quick and penetrating glance […]; he could not forget that glance, which continued to burn before his eyes. It seemed to him like a cold fire, like a distant light, perhaps because he had recalled the impression he had when, the evening prior, while he was looking at Yōko’s face reflected in the train window, the light from the mountains passed behind her face and was superimposed on her pupils, illuminating them, and he was captivated by the ineffable beauty of that image. Along with that memory, another image immediately came to mind, that of Komako’s red cheeks in the mirror, against a snowy landscape” [

2] (p. 43).

In this case too we find a kind of flow of cinematic images. Later in the novel, we read the following description of Yōko’s voice: “It seemed that somehow the echo [of her voice] reverberated somewhere in those snowy mountains” [

2] (pp. 64–65). And, toward the end of the work, he writes: “More than the clatter of the train, the sound of Yōko’s voice lingered in the air. Its echo, vibrating with a very pure feeling of love, appeared to ring out into infinity” [

2] (p. 91). Here time expands with the protagonist’s perception of the sound.

Shimamura comes to this hot spring where, however, he has been before; he is a typical

sukimono, that is, a pleasure seeker; he expects nothing from his love affairs except the joy they bring him. He continues to search for something, however, a force that will confirm the meaning of life for him. The rarefied, oneiric atmosphere in which the two lovers experience their emotions is interrupted abruptly by Shimanura’s departure, which assumes a dramatic quality due also to the Yōko’s unexpected announcement of the death of Yukio, a person who was important in Komako’s life and whom she described in the first page of her diary. The second part of the novel, then, opens with Shimamura’s departure for Tokyo: “As soon as the train was in motion, there was a flash of light in the window of the train station waiting room. In that light Komako’s face lit up for a brief moment, but in that instant her cheeks seemed to him as red as they were in the mirror that morning with the snow. Once again, that color in Shimamura’s mind, marked the line that separated him and reality” [

2] (p. 65). In this cold landscape, Komako possesses a glowing quality that dissipates the cold of this snow; when he caresses her hair, however, he tells her that it is cold—an observation that depicts her as not very sunny. She is endowed with some element of the snow country. The love story involving Komako unfolds with the same nuances and the same evocative images. It seems that the two protagonists can continue to move forever without ever colliding, in a dimension that seems unreal:

Looking heavenward, the stars, which seemed too numerous to be real, stood out so vividly against the dark sky that they seemed to fall at an incredible speed. As those stars approached the earth, the sky fell increasingly into the darkness of night. The silhouettes of the mountains along the border were by now undiscernible, but their presence loomed on the edge of the starry sky, a presence made even more massive by the blackness. Everything melted into a cold, silent harmony [

2] (p. 33).

When she felt Shimamura approaching, the woman pressed her body against the railing. Her pose did not betray weakness; in fact, no image could express greater tenacity than that image of her standing against the night background. However, despite the fact that the mountains were black, for some reason they seemed white with snow to him, and that caused him to perceive in them a diaphanous quality, a sense of melancholy and solitude [

2] (p. 34). (See

Figure 8)

We also have the following passage:

From the grey sky framed by the window, large snowflakes floated gently toward them like peony petals. There was an almost unreal tranquility in the view. Shimamura, who had not slept enough, looked out dazed. […]; recalling the mirror of the morning of the snows, near the end of the previous year, he turned toward the dressing table. In the mirror, those cold petals of snow seemed even bigger, producing white streaks around Komako who was wiping with a wet cloth her neck, left uncovered by the kimono” [

2] (p. 114).

But, if it is life, nature is also death. Everything reminds Shimamura of death: the frigid air, Komako’s cold hair, suffering insects: “He often stopped to observe dying insects, examining their agony. Now that autumn was getting colder and colder, there was not a day that some insect did not die on the tatami mat in his room” [

2] (p. 100). We see death in the opening pages of the novel when Shimamura is on the train with a dying man next to Yōko. Shimamura’s entry into this world joins together two elements, namely, life and death. (See

Figure 9)

The strange flame in Yōko’s gaze and the bright red of Komako’s cheeks reappear in the nocturnal landscape at the end of the novel, in the dramatic scene of the fire juxtaposed to the splendid image of the Milky Way, which symbolizes the desire for eternity and a vital essence (See G. Amitrano, “Passi sotto la neve” [“Footprints beneath the snow”], introduction to Y. Kawabata [

2] (p. xii)):

The Milky Way enveloped the dark earth in its bareness; it had come down, close. It had a startling sensuality. Shimamura had the impression that his own small shadow was projected from the earth to the Milky Way. The night was so clear that not only could you see all the stars individually, but even the grains of silver that made up the luminous clouds scattered throughout the galaxy could be made out, and the infinite depth of the Milky Way drew his gaze, sweeping it up into itself. […] Komako ran toward the dark mountain over which the Milky Way was suspended.

She seemed to keep the hem of her kimono lifted with her hands and every time her hands moved as she ran, the hem would rise or fall, its red color clearly visible against the snow illuminated by the moon. […] Her eyes were cold, but her cheeks were afire. Shimamura’s eyes were also moist. He blinked and the Milky Way filled his gaze. […] The Milky Way seemed to move with them as they ran and Komako’s face appeared moistened by its light. […] Like a great aurora, the Milky Way swept away Shimamura’s body giving it the feeling of finding itself at the extreme edge of the earth. There was a chilling solitude, but a sensual awe as well […] Shimamura suddenly remembered when, years earlier, in the train on which he was travelling toward the village where he was to see Komako again, a light emanating from the mountain appeared in the centre of Yōko’s face, and he felt his heart shudder at that recollection. It was as though those years spent with Komako were illuminated in an instant [

2] (pp. 127, 129, 135).

Here too the landscape plays a key role in highlighting Shimamura’s isolation and detachment from the rest of the world. The reader is left suspended in an oneiric atmosphere, entranced by the lyricism of the closing images. There is no real conclusion and a sense of incompleteness prevails because the structure of the narrative as a whole has a fragmentary quality. In fact,

Yukiguni, was published in installments. The author began to write the novel in 1934, but the final version was printed in 1947. (On the novel

Yukiguni and on Yasunari Kawabata in general see G. Amitrano [

5], S. DeVere Brown [

6], Y. Ichihara [

7], S. Katō [

8], D. Keene [

9], A.V. Liman [

10], F. Mathy [

11], M. Lippit [

12], G. Parise [

13], C. Pes [

14], C. Sakai [

15], M. Scalise [

16], E.G. Seidensticker [

17], D. Tomasi [

18], K. Tsuruta [

19], and U. Makoto [

20])