Agogic Principles in Trans-Human Settings †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Development of Transhuman Systems

3. Agogic Principles

- Activities are set in accordance with the needs of participating actors under the given conditions and capabilities to act

- Each actor has certain resources that are not only the starting point, but rather design entities. They are accepted to be limited.

- Actors determine their way and pace of developments, as development needs to in balanced with the current conditions. Both, active participation, and retreat are part of development processes.

- Empathy as sensitive understanding of others

- Appreciation of another personality without preconditioning acceptance and respect

- Congruence meaning the authenticity and coherence of one’s person and behavior

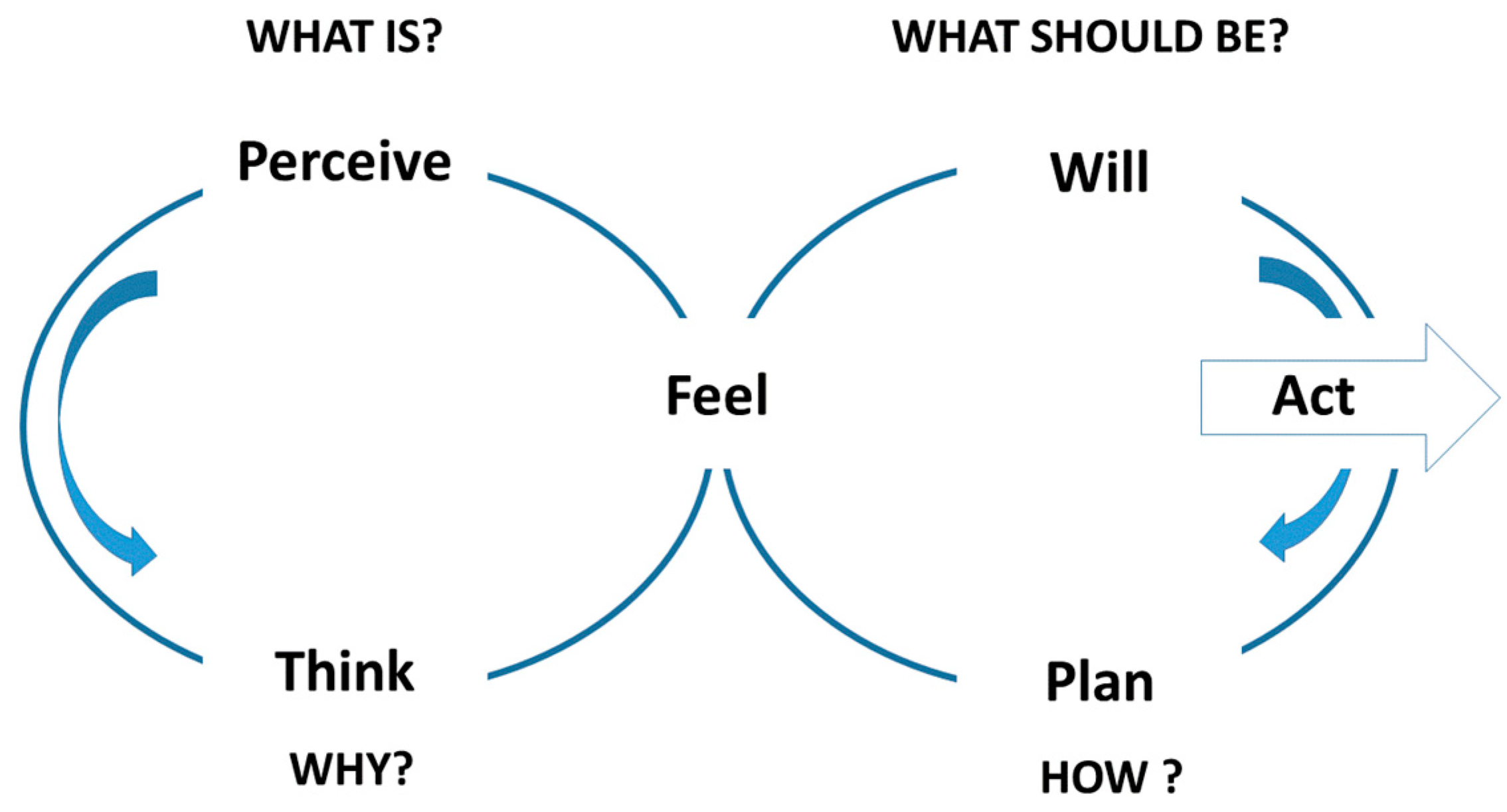

- WHAT IS? What did you see, hear, smell, tasted, feel? What happen, when and how? Can you describe in detail?

- WHAT SHOULD BE? Which perspective, which sense do you see? What needs to be achieved? Which priorities do you want to set? What do you want exactly? And why? Which state satisfies you?

- WHY? Which meaning do the observations have for you? Which relations do you recognize? What do you reckon? How can you explain that? What are your conclusions?

- HOW? How to proceed? Which means shall be used? Which tactics shall we chose? What is to be done? Who does what, with what, whom, when and how?

4. Towards Agogic Development Settings

- Open: In case development content is found to be incomplete or poorly organized, any actor or system should edit it the way it fits individually.

- Incremental: Development content can be linked to other development content, enforcing system thinking and contextual inquiry.

- Organic: The structure and content of a system under development is open to continuous evolution.

- Mundane: A certain number of conventions and features need to be agreed for shared access to development content.

- Universal: The mechanism of further development and organizing are the same as creating so that any actor, system, or system developer can be in both roles, an operating and a development system.

- Overt: The output suggests the input required to reproduce development content.

- Unified: Labels are drawn from a flat space so that no additional context is required to interpret them.

- Precise: Development content items are titled with sufficient precision to avoid most label or name clashes.

- Tolerant: Interpretable behavior is preferred to error messages.

- Observable: Activities involving development content or structure, specifications, can be watched and reviewed by other stakeholders, both on the cognitive and social level.

- Convergent: Duplication can be discouraged or removed by identifying and linking similar or related development content.

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

- (1)

- Humanity stands to be profoundly affected by science and technology in the future. We envision the possibility of broadening human potential by overcoming aging, cognitive shortcomings, involuntary suffering, and our confinement to planet Earth.

- (2)

- We believe that humanity’s potential is still mostly unrealized. There are possible scenarios that lead to wonderful and exceedingly worthwhile enhanced human conditions.

- (3)

- We recognize that humanity faces serious risks, especially from the misuse of new technologies. There are possible realistic scenarios that lead to the loss of most, or even all, of what we hold valuable. Some of these scenarios are drastic, others are subtle. Although all progress is change, not all change is progress.

- (4)

- Research effort needs to be invested into understanding these prospects. We need to carefully deliberate how best to reduce risks and expedite beneficial applications. We also need forums where people can constructively discuss what should be done, and a social order where responsible decisions can be implemented.

- (5)

- Reduction of existential risks, and development of means for the preservation of life and health, the alleviation of grave suffering, and the improvement of human foresight and wisdom should be pursued as urgent priorities, and heavily funded.

- (6)

- Policy making ought to be guided by responsible and inclusive moral vision, taking seriously both opportunities and risks, respecting autonomy and individual rights, and showing solidarity with and concern for the interests and dignity of all people around the globe. We must also consider our moral responsibilities towards generations that will exist in the future.

- (7)

- We advocate the well-being of all sentience, including humans, non-human animals, and any future artificial intellects, modified life forms, or other intelligences to which technological and scientific advance may give rise.

- (8)

- We favour allowing individuals wide personal choice over how they enable their lives. This includes use of techniques that may be developed to assist memory, concentration, and mental energy; life extension therapies; reproductive choice technologies; cryonics procedures; and many other possible human modification and enhancement technologies.

References

- More, M. Transhumanism: Towards a futurist philosophy. Extropy 1990, 6, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom, N. The future of humanity. In New Waves in Philosophy of Technology; Olsen, J.-K.B., Selinger, E., Riis, S., Eds.; Palgrave McMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 186–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom, N. Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, M.; Haraway, D. Anthropocene, capitalocene, plantationocene, chthulucene; Donna Haraway. in conversation with Martha Kenney. In Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters among Aesthetics, Environments and Epistemologies; Davis, H., Turpin, E., Eds.; Open Humanity Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Double-Loop Learning. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt, M. DARPA’s Programs in Enhancing Human Performance. In Converging Technologies for Improving Human Performance: Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Information Technology and the Cognitive Science; NBIC-report; Roco, M.C., Schummer, J., Eds.; National Science Foundation: Arlington, VA, USA, 2002; pp. 337–341. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzweil, R. The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- More, M.; Vita-More, N. (Eds.) The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary Essays on the Science, Technology, and Philosophy of the Human Future; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. Anthropocene, capitalocene, plantationocene, chthulucene: Making kin. Environ. Hum. 2015, 6, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Educational Essays; Cedric Chivers: Bath, UK, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process; Heath & Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 5126. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, S. The Reflective Practitioner and the Curriculum of Teacher Education. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association of Teacher Educators, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 5–8 February 1990; Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED319693.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2017).

- Schön, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Die Ökologie der Menschlichen Entwicklung; Klett-Cotta: Stuttgart, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.R. Die klientenzentrierte Psychotheraphie; Kindler: München, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone, J.M.; McElroy, M.W. Key Issues in the New Knowledge Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, C. Wiki: A technology for conversational knowledge management and group collaboration. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stary, C. Agogic Principles in Trans-Human Settings. Proceedings 2017, 1, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/IS4SI-2017-03949

Stary C. Agogic Principles in Trans-Human Settings. Proceedings. 2017; 1(3):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/IS4SI-2017-03949

Chicago/Turabian StyleStary, Christian. 2017. "Agogic Principles in Trans-Human Settings" Proceedings 1, no. 3: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/IS4SI-2017-03949

APA StyleStary, C. (2017). Agogic Principles in Trans-Human Settings. Proceedings, 1(3), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/IS4SI-2017-03949