1. Introduction

Aromatic and medicinal plants (MAPs) represent one of the most valuable botanical resources used worldwide for human health and well-being. More than 80% of the global population relies on plant-based remedies for primary healthcare needs, highlighting their critical role in developed and developing countries [

1]. They constitute the basis of traditional medicine systems, and they are increasingly integrated into modern healthcare due to their rich content of compounds, including essential oils, flavonoids, and terpenoids, which have antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties [

2]. Additionally, MAPs supply materials for the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industries [

3,

4]. The growing interest in natural health products has emphasized the need for sustainable cultivation practices to ensure high-quality plant material and preserve biodiversity [

5].

Sage (

Salvia officinalis) belongs to the Lamiaceae family and is one of the world’s most valued MAPs, widely cultivated for its content of bioactive compounds. Sage plays a significant role in traditional medicine and is increasingly used in modern phytotherapy, nutraceutical formulations, and functional foods [

6,

7].

Nitrogen (N) is one of the most essential nutrients for plant growth because it is a fundamental component of amino acids, proteins, nucleic acids, and numerous metabolites that regulate physiological and biochemical processes. Nitrogen availability directly influences cell division, photosynthesis, enzyme activity, and biomass production, making it a central determinant of the overall plant growth and the quality of the harvested product [

8,

9,

10]. In MAPs, nitrogen plays an additional role in enhancing secondary metabolism, contributing to the synthesis of essential oils, phenolic compounds, and other constituents that determine their therapeutic value [

11].

Nowadays, organic fertilizers are preferred over synthetic ones because they improve soil fertility through mechanisms that enhance both physical and biological properties. Organic fertilizers also increase soil organic matter content, enhance soil structure, water capacity and aeration, and stimulate soil microbial activity. Moreover, organic inputs promote nutrient cycling and the long-term accumulation of soil carbon, thereby improving soil fertility and supporting sustainable crop production [

12,

13,

14]. For all these reasons, organic fertilization is recognized as a more environmentally friendly option that supports soil biodiversity, reduces environmental pollution, and improves nutrient use efficiency in various cropping systems [

15,

16].

Nitrogen-enriched sea-derived organic amendments, such as seagrass compost, seaweed-based fertilizers, mussel and oyster shells, as well as other aquaculture by-products, are highly valuable in agricultural section due to their ability to improve soil fertility, nutrient availability and overall crop performance and productivity. These products supply organic nitrogen together with essential macro- and micronutrients, while also enhancing soil structure, microbial activity, and organic matter content [

17,

18]. Their nutrient release supports plant growth and reduces nutrient losses. Additionally, sea-derived composts contain bioactive compounds that can stimulate root development and improve secondary metabolism not only in various crops but also in aromatic and medicinal plants [

19]. A study has shown that when mixed with yard waste, compost produced from

P. oceanica can effectively fertilize vegetable crops such tomato and lettuce.

P. oceanica compost provided nutrient availability without inducing phytotoxic effects. The findings of this investigation demonstrate that sea-based compost not only supports crop productivity but also contributes to environmentally friendly nutrient management and coastal waste valorization [

20].

Large amounts of

P. oceanica biomass and other marine by-products accumulate as waste, often creating environmental management challenges [

21]. Rather than being discarded, these materials can be used as soil amendments. This challenge is closely connected to the framework of the circular economy, which promotes materials to be reused, recycled and transformed into new products [

22,

23]. The utilization of

P. oceanica compost and mussel shells in agriculture fits with the principles of the circular economy. For aromatic and medicinal plants, which are often sensitive to soil fertility and nutrient balance, such amendments can support healthier plant growth, improved productivity and higher-quality plant material. By converting coastal waste into agricultural resources, this strategy mitigates disposal problems and contributes to more sustainable and resilient farming systems adapted to Mediterranean conditions [

24,

25].

This study addresses two environmental challenges: the decrease in using synthetic nitrogen fertilizers and the opportunity to find a useful, sustainable solution for coastal and aquaculture wastes that are often difficult to manage. With this in mind, we explored whether marine-based organic amendments could be used as part of a circular fertilization approach for sage cultivation. Specifically, we expected that Posidonia oceanica compost (as an organic nitrogen source), together with mussel shell powder (a CaCO3-rich material with liming potential), would raise soil pH in acidic conditions, support nutrient availability and nitrogen processes in the soil, and ultimately improve sage performance. We therefore hypothesized that 1. compost application would increase sage growth, plant nitrogen content, N uptake, and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) relative to the unfertilized control; 2. mussel shell addition would further enhance these responses by decreasing soil acidity; and 3. the combination of Posidonia oceanica compost and mussel shell would result in improved growth and traits related to nitrogen.

For all these reasons, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of P. oceanica compost with mussel shells as soil amendments on agronomic characteristics, productivity, nitrogen plant content and nitrogen indices in Salvia officinalis cultivation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

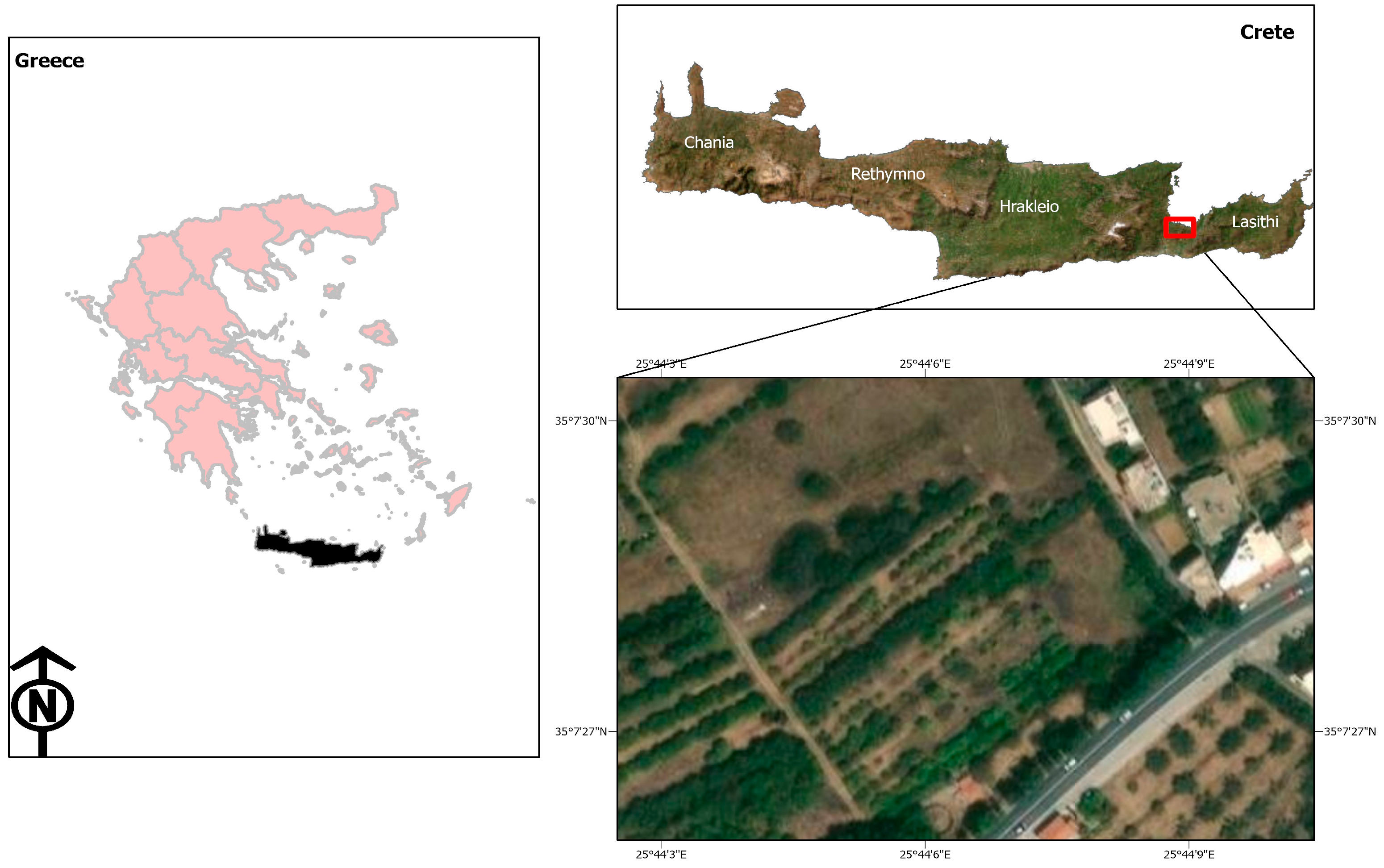

The experimental study was carried out on the southern island of Crete (Greece), at the campus of the Department of Rural Development and Food. The campus is located in Istron Kalou Xoriou, within the municipality of Agios Nikolaos (Prefecture of Lasithi). The site is situated at an elevation of 50 m above sea level, with precise geographic coordinates of 35°07′28.3″ N latitude and 25°44′07.8″ E longitude (

Figure 1).

2.2. Soil Selection

The objective of this study was to perform experimental investigations under acidic soil conditions. Accordingly, soil samples were obtained from 20 agricultural fields across the broader area. Subsequent pH measurement was conducted and the soil sample with the lowest pH value was selected as the representative acidic substrate for the experiments.

2.3. Meteorological Data

Meteorological data were obtained from the nearby weather station operated by the Institute of Environmental Research and Sustainable Development, as part of the Hellenic National Observatory of Athens.

2.4. Plant and Mussel Material

Sage plants were obtained from a commercial nursery located in Sitia, Crete, Greece (named Anagnostakis Ioannis). Mussel shells of the Mediterranean species were obtained from a seafood processing facility (Olympias A.B.E.E., Kimina Thessalonikis). The shells were rinsed with distilled water, placed on metal trays, and finally dried in a forced-air oven at 40 °C for 48 h. Then the dried shells were ground with a mortar pestle and sieved through a steel mesh (<1 mm). This process produced a particle-size fraction (fine powder, FP < 1 mm).

2.5. Soil, Mussel, and Plant Analysis

The soil sample used for the experiment was air-dried at 40 °C for 24 h, passed through a 2 mm sieve and then analyzed for the following physicochemical properties: pH, particle size distribution (sand, silt, clay), organic matter (OM), total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (P), and exchangeable potassium (K). Furthermore, mussel shells were analyzed for pH, calcium carbonate (CaCO

3), organic matter (OM), total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (P), and exchangeable potassium (K). All the above measurements were conducted according to Rowell [

26]. Moreover, the total nitrogen (TN) content of plant material was measured using the Kjeldahl method with a Bucchi UBK apparatus (VELP China Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China).

2.6. Pot Experiment Setup

The experimental design consisted of three nitrogen fertilization schemes (0, 40, and 80 kg ha

−1) and four different mussel shells portions (0 g/pot, 50 g/pot, 100 g/pot, and 200 g/pot). In total, 9 treatments were established and each treatment was replicated three times, resulting in 27 pots. A detailed description of the treatments is presented in

Table 1.

Before transplantation, the PL50, PL100, PL200, PH50, PH100, PH200 treatments were amended with the appropriate dose rates calculated per 10 kg of soil.

Plants were transplanted into pots (35 cm in height and 36 cm internal diameter) on 2 May 2023, and irrigation was applied immediately. Throughout the experiment, the pots were watered as needed to preserve stable soil moisture conditions. The pots were arranged so that the inter-pot spacing corresponded to an area of 1 m2. Fertilization was conducted manually using P. oceanica Compost (Posidonia Compost Ltd., Cyprus), composed of 25–35% organic matter, 0.8–1% total N, 0.32–0.50% P2O5, and 0.90–1% K2O. The compost application was adjusted so the nitrogen doses per pot were equivalent to 40 kg ha−1 and 80 kg ha−1. In the 1st year, half of the compost dose was applied with the transplant on 2 May 2023, and the other half on 10 July 2023. For the 2nd growing period, half of the dose was incorporated on 5 May 2024, followed by the other half of the compost after the first cutting in June 2024. During the growing seasons, three cuttings were conducted on 30 August 2023, on 28 June 2024, and on 15 September 2024. The plants were manually harvested at a height of 5 cm above the soil surface and immediately weighed to determine the fresh biomass using a portable scale. The plants from each pot were divided into leaves, branches, and stems and each edible material was oven-dried at 40 °C until a constant weight was achieved; the plants were then reweighed to obtain the dry biomass of whole plant and leaf material. The same day, before the harvest, the plant height was recorded using a measuring tape.

2.7. Experimental Measurements

Throughout the growing seasons, several plant traits were evaluated. The parameters measured included plant height, total plant biomass, leaf yield, total plant nitrogen content (TN), N uptake, and Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE). Moreover, in all treatments amended with powder mussel shell, the soil pH was calculated at each harvest event.

2.8. Nitrogen (N) Indices

Total nitrogen (TN) uptake by plants was quantified through the determination of nitrogen content in the aboveground biomass. The N uptake was determined using the following formula [

27]:

Furthermore, the nitrogen use efficiency (NUE, kg kg

−1), which represents the efficiency with which the plant converts absorbed nitrogen into biomass, was calculated according to the formula provided below [

28,

29].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical data were conducted using the STAGRAPHICS Centurion software (version 18.1.01; Statgraphics Technologies, Inc, The Plains, VA, USA), with significance set at p < 0.05. Differences between treatments (M, PL0, PL50, PL100, PL200, PH0, PH50, PH100, PH200) were evaluated using one-way ANOVA, with “treatment’’ as a fixed factor. Where ANOVA indicated significant differences (p < 0.05), means were compared using Fisher’s LSD procedure (α = 0.05). A two-way ANOVA was performed for the parameters plant height, total fresh weight, total dry weight, fresh leaf weight, dry leaf weight, and total N, N uptake, and NUE. The independent parameters were fertilizer rate and shell mussel powder dose. All experiments were performed in triplicate at 3 different time points.

3. Results

3.1. Meteorological Data

Figure 2 summarized the meteorological conditions during the experimental period. Total rainfall differed between the two growing periods, reaching 270.2 in the first period and 139.6 mm in second. Mean air temperature (°C) was comparable between years (20.8 °C in 2023 and 21.7 °C in 2024). The highest monthly temperature values were observed in July 2023 (30.9 °C), in July 2024 (31.5 °C), and in August 2024 (31.1 °C).

3.2. Physicochemical Properties of Soil and Mussel Shell Powder

Table 2 presents the initial physicochemical characteristics of the soil. The soil used in the experiment was classified as sandy clay loam, with an acidic pH (5.10) and characterized by relatively low organic matter and total nitrogen, providing a suitable baseline to evaluate liming and organic N inputs.

Table 3 reports the properties of mussel shell powder. Mussel shell powder was characterized by a high value of calcium carbonate content (75.3%), supporting its use as a liming material under acidic soil conditions and organic matter content (2.76%).

3.3. Soil pH of the Amended Treatments

The pH of the treatments amended with powdered mussel shell was determined at the time of harvest. The pH results are illustrated in

Table 4. Soil pH increased with shell dose in both compost levels (PL and PH). The 50 g pot

−1 rate produced a moderate increase, whereas rates of 100 and 200 g per pot increased the pH above 6, shifting the soil from moderately acidic to near-neutral conditions. Notably, the 200 g dose increased the soil pH to 6.6 and 6.7, bringing the pH closer to neutral from its moderately acidic status, confirming the strong liming capacity of the shell material under acidic conditions. Importantly, these pH increases were maintained across harvests, indicating a stable liming effect throughout the experimental period.

3.4. Plant Height (cm/plant/pot)

The data on plant height are shown in

Table 5. The plant height exhibited consistent and progressive vegetative development from August 2023 to September 2024. Compost application significantly enhanced plant height compared with the unfertilized control (M) and mussel shell powder provided an additional benefit within both compost levels. The tallest plants were consistently observed under PH200 at all harvests, demonstrating that the combined high compost level and highest shell dose maximized growth. Within PL treatments (PL50, PL100 and PL200), mussel shell addition increased height relative to PL0, with the largest increases recorded in the second harvest (13.3, 14.9, and 21.8% for PL50, PL100, and PL200, respectively). A similar dose-dependent pattern was found within the PH pots, where height increased by 15.7, 16.6, and 21.1 for PH50, PH100, and PH200 relative to PH0. However, no significant differences were detected between PL50 and PL100, or between PH50 and PL100 in the second and third cuttings. The results indicated a clear positive response to shell addition at the higher compost level.

3.5. Fresh and Dry Weight (g/plant/pot) of Total Plant and Leaf Material

Table 6A,B presents the total fresh and dry biomass, while

Table 7A,B shows the leaf fresh and dry weight for the three harvest periods. According to the results, biomass responded strongly to the amendment schemes. Fresh and dry weights increased significantly from the unfertilized control (M) to compost-amended treatments and further enhanced by increasing mussel shell dose. The combined treatments (PH200) consistently produced the highest total and leaf fresh weights in all harvests, and significant differences were observed between the control and all amended treatments.

Dry biomass followed the same pattern and showed a stable ranking across harvests, with values increasing in the following order: M < PL0 < PH0 < PL50 < PL100 < PL200 < PH50 < PH100 < PH200. This supports a clear dose–response effect of both compost input and mussel shell powder addition on productivity. Within the PL and PH treatments, the largest increases were observed in the second harvest (June 2024) between PL0–PL200 and PH0–PH200, with raised values of 34.9% and 52.1%. Additionally, in the third cutting, the increase between PL0–PL200 and PH0–PH200 were 35.6 and 51.2%, respectively.

3.6. Total Nitrogen Content

The Total nitrogen (TN) concentration of plants is presented in

Table 8. Plant TN content differed significantly among treatments and showed a stable trend across all cuttings. TN increased from unfertilized control (M) to compost-amended treatments and rose further with mussel shell powder addition, indicating a clear amendment-intensity effect on plant N status. The highest values were recorded in LH200 pots in all harvest periods, with TN ranging from 0.863 to 0.910% in the control to 1.967–2.117% in PH200. In PL and PH treatments, TN increased progressively with mussel shell dose and the response was stronger at the higher compost level. In June 2024 TN increased by 8.86–15.64% from PL0 to PL50–PL200 and by 20.50–41.36% from PH0 to PH50-PH200. A similar pattern was noticed in September 2024, where TN increased by 7.51–13.97% within the PL treatments and by 20.47–41.89% within the PH pots relative to their no shell controls. These results indicate that mussel shell powder addition amplified the compost effect on TN concentration, particularly under higher compost application.

3.7. Nitrogen Indices

3.7.1. N Uptake (g/plant)

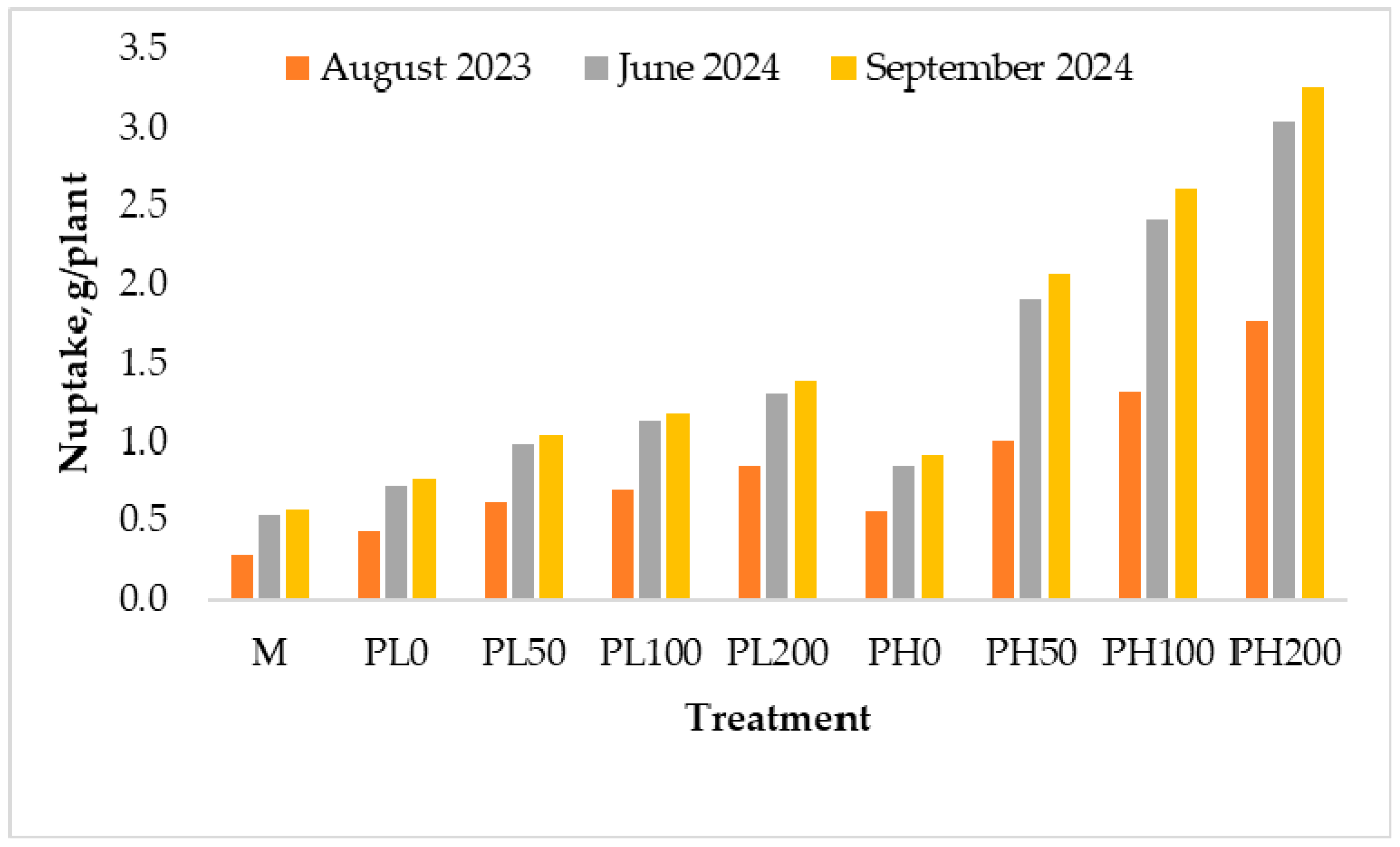

The results of N uptake are provided in

Figure 3. N uptake was affected by the fertilization and mussel shells. According to the one-way ANOVA results (

Table 9), there were statistically significant differences between the treatments. Compost-amended treatments exhibited higher N uptake than the control, while mussel shell addition raised uptake more within each compost dose. The highest values were recorded in PH200 treatment (1.762 g/plant in August 2023, 3.043 g/plant in June 2024, and 3.248 g/plant in September 2024), provoking a rise of 68.19% in first harvest, 71.91% in second, and 71.66% in % third cutting in comparison with PH0. The results indicate that combining organic N supply with pH amelioration maximized plant N acquisition.

3.7.2. Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE, kg kg−1)

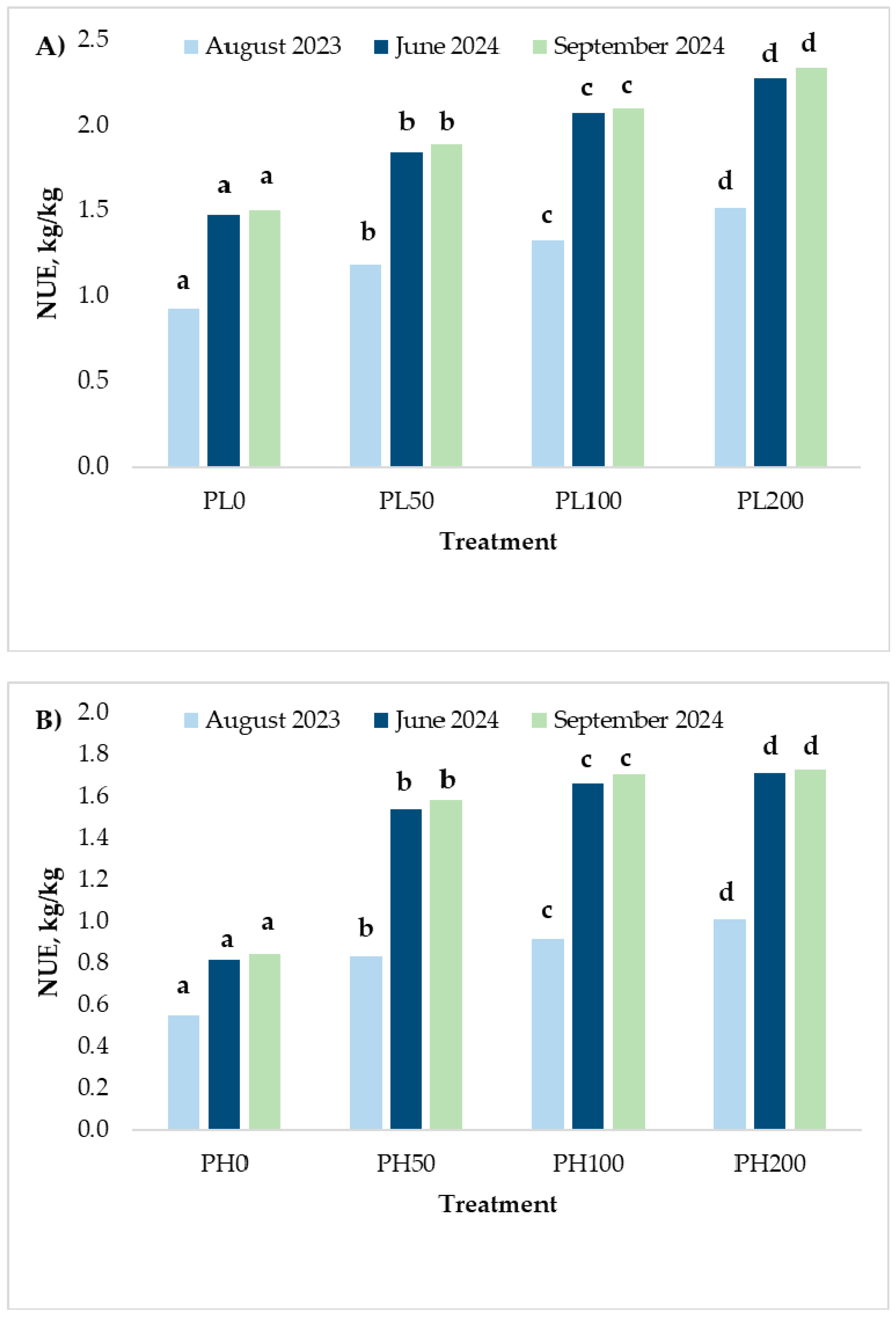

In

Figure 4A,B, the nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) results in sage cultivation are reported. NUE increased with amendment intensity across all three harvests. NUE was highest in PH200, followed by PH100, which indicated that the combined high compost level and high mussel shell dose can produce the most efficient conversion of supplied nitrogen into biomass. In both compost applications, shell addition significantly improved NUE compared with the no shell treatments (PL0 and PH0). In the PL treatments, the highest dose PL200 increased NUE by 35–39% relative to PL0, while in the PH pots, PH200 increased NUE by 46–52% compared with PH0. Differences between shell doses (50 vs. 100 g pot

−1) were generally smaller and in some harvests, no statistically significant differences were detected, indicating that the strongest contracts occurred between the no shell treatments and the highest shell dose. Overall, the findings indicate that increasing soil pH with mussel shell powder enhanced the effect of organic fertilization on NUE, with the strongest improvement observed at the higher compost dose.

3.8. Two-Way ANOVA

For the parameters fresh weight, dry weight, fresh leaf weight, dry leaf weight, N uptake, and NUE, equality of variances was not satisfied (Levene’s test of equality of variance), as such a more stringent level of true statistical difference (p < 0.01) was chosen for the two-way ANOVA. For the parameters plant height (p = 0.940), fresh weight (p = 0.01), dry weight (p = 0.04), leaf fresh weight (p = 0.202), leaf dry weight (p = 0.04), and NUE (p = 0.627), there was no significant interaction between fertilizer rate and shell dose. However N uptake and total N were affected by the interaction between the two treatments; for total N, a statistically significant main effect of fertilizer dose, F (2, 72) = 701.61, p < 0.001, and a significant main effect of shell dose were observed, F (3, 72) = 441.80, p < 0.001. In addition, the interaction between fertilizer dose and shell dose was statistically significant, F (3, 72) = 187.20, p < 0.001. For N uptake, a significant main effect of fertilizer dose, F (2, 72) = 49.17, p < 0.001 and a significant main effect of shell dose were observed, F (3, 72) = 32.66, p < 0.001. Furthermore, the interaction between fertilizer dose and shell dose was statistically significant, F (3, 72) = 10.29, p < 0.001. In general, both parameters (total N and N uptake) were positively affected by the addition of the shell treatment.

5. Conclusions

This investigation demonstrated that two sea-derived materials provided unique but also complementary benefits. The compost originated from P. oceanica operated as a source of organic nitrogen and increased the soil organic matter, which improved the vegetative characteristics and enhanced nitrogen status of plants. This was evidenced by the results, which show increases in plant height, biomass (fresh and dry), plant nitrogen concentration, N uptake, and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). In contrast, the use of mussel shell powder acted as a liming material, significantly raising soil pH and creating a more favorable environment for nutrient availability and root function. Moreover, the addition of mussel shell powder further enhanced agronomic parameters and nitrogen-related indices, indicating that the alleviation of soil acidity amplified the benefits of organic fertilization. The combined application (P. oceanica and mussel shell), especially at higher amendment doses, exhibited a synergetic effect, enhancing nutrient supply from compost and improving pH values through the use of mussel shell material. The incorporation of sea-derived organic inputs improved the capacity of plants to acquire and utilize nitrogen.

The findings of this investigation support the circular economy principles by demonstrating that aquaculture by-products can be repurposed as effective soil amendments. Converting P. oceanica residues into compost and reusing mussel shells as liming material creates value for such materials, which would otherwise require disposal in landfills.

The results of this study were obtained from a controlled pot experiment using a single type of acidic soil. Therefore, their application to field agricultural systems should be made with caution. Under field environments, the variability of various parameters may modify the amendment performance. Consequently, trials at multiple sites and seasons under different soil conditions are required to verify the consistency of these effects, refine optimal application rates, and assess long-term impacts on soil fertility and nitrogen dynamics before broad agronomic recommendations can be made.