1. Introduction

Today, the most used engineering method for the performance analysis of wind turbines is still the Blade-Element/Momentum Theory (BE/M-T), which stems from the coupling of the Momentum Theory (MT) and the Blade-Element Theory (BET). It is well known that this approach, relying on the actuator disk concept, is affected by several inherent approximations which often require the introduction of correction factors. For example, the MT disregards the pressure contribution on the lateral surface of the infinitesimal streamtubes ingested by the disk, thus neglecting the two-dimensional effects associated with the wake divergence [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Moreover, the wake rotation is simply taken into account in a linearised fashion, a fact that introduces significant errors, especially for low values of the tip speed ratio [

6,

7]. A consolidated and reliable correction for these two inexactnesses, which can lead to appreciable errors for high values of the rotor load, does not exist. The nature of the actuator disk model also requires the introduction of tip and hub correction factors to take into account the effects of a finite number of blades on the rotor performance [

1,

8,

9]. There exist also several empirical relations to modify the momentum theory equation outside the classical windmill wake-state [

10,

11,

12]. Finally, some corrections for dynamic stall [

13,

14], tower [

15], and Himmelskamp [

16] effects are also generally introduced in the BE/M-T.

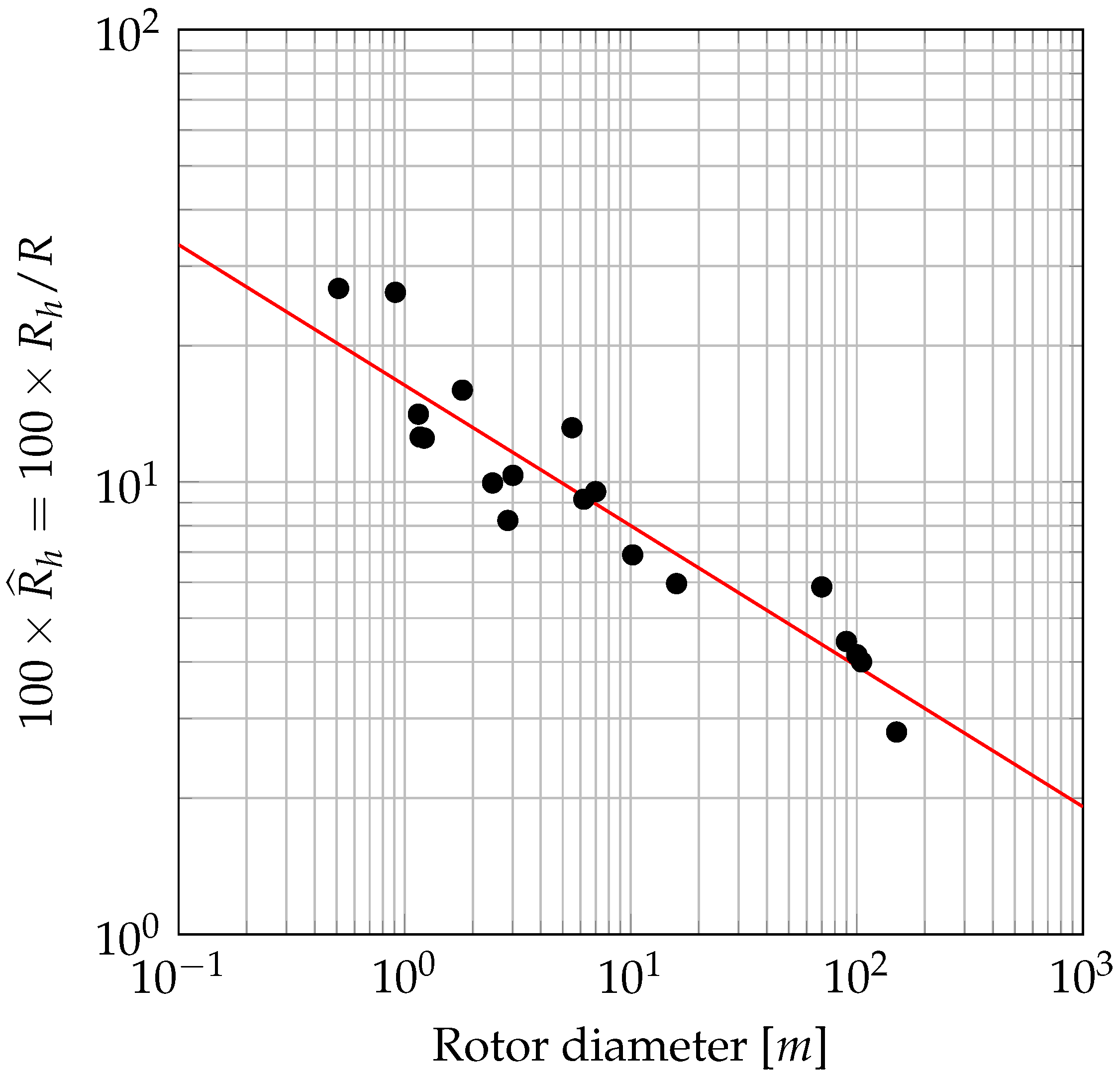

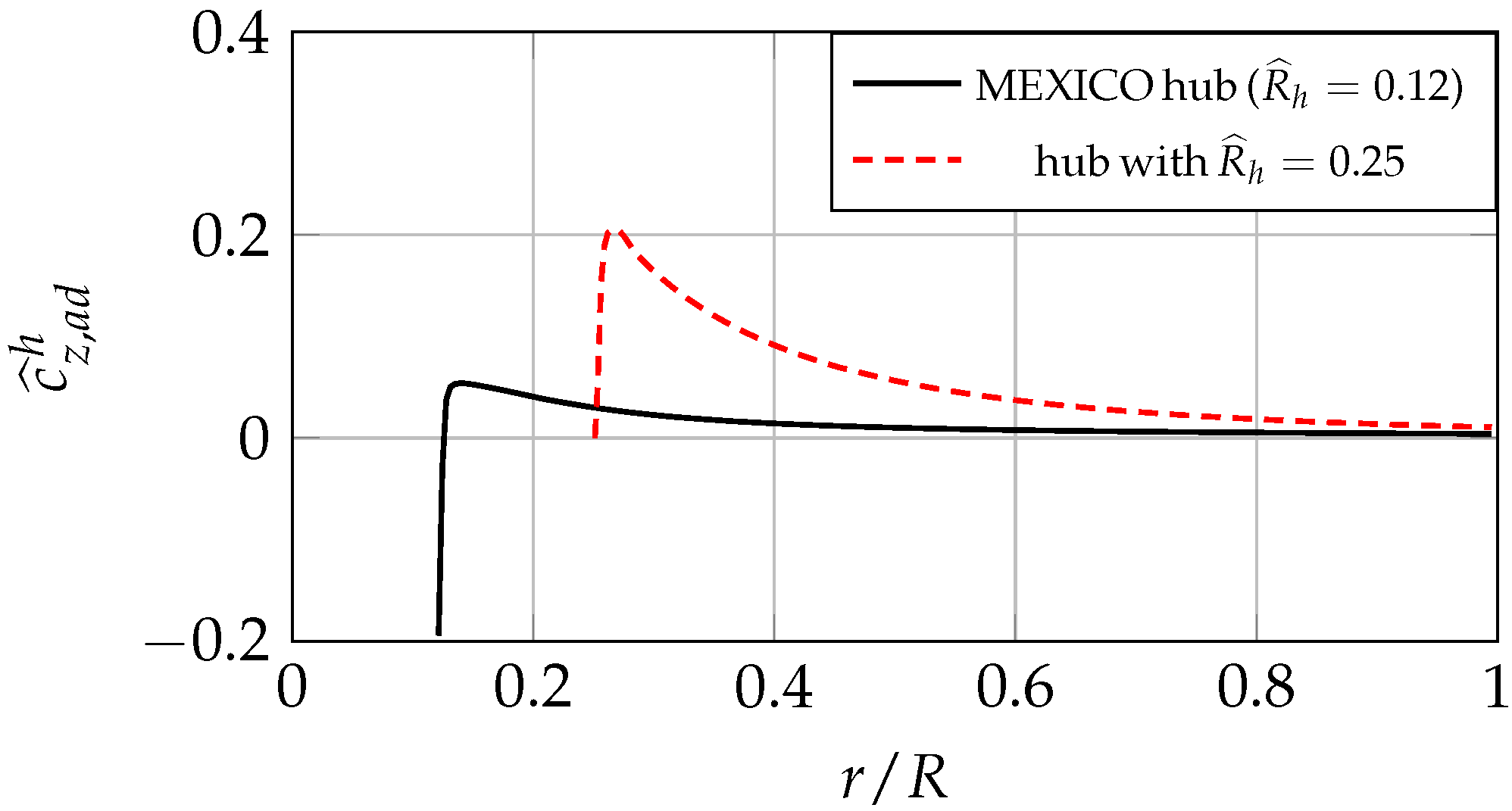

Despite this great variety of engineering models typically used to improve the accuracy of the BE/M-T, a correction for the hub blockage effect does not exist yet [

17]. This phenomenon is typically disregarded in medium- or large-sized wind turbines which are generally characterised by low or moderated values of the ratio between the hub and rotor radius

. Nevertheless, in small-sized devices, the value of this quantity can significantly rise up to 25–30%. This is evident from

Figure 1 (see also [

18]), which, for several commercial wind turbines, shows a clear increasing trend in

when the rotor diameter decreases.

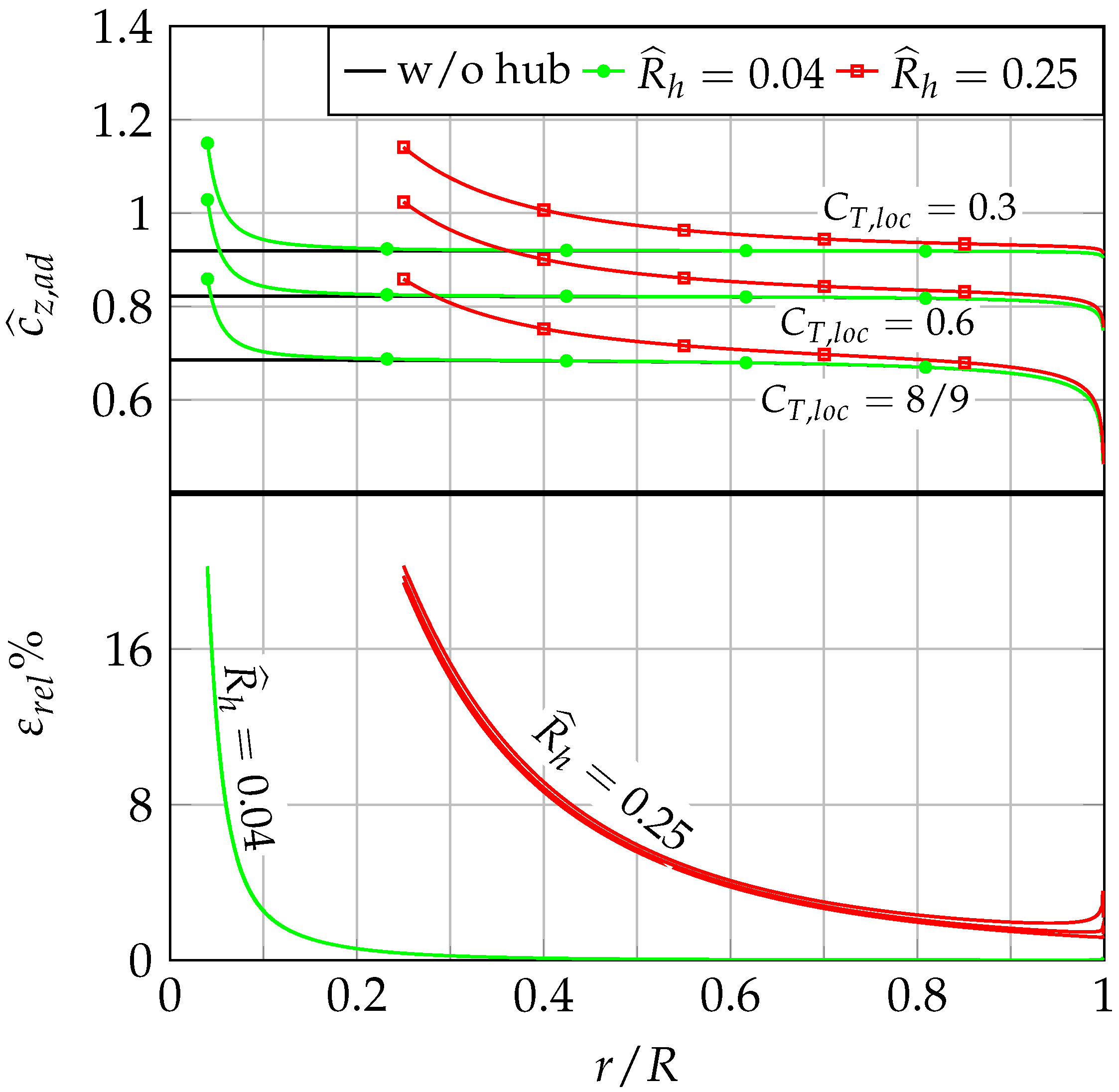

Bontempo and Manna [

18] evaluated the influence of the hub presence using a ring-vortex free-wake uniformly loaded actuator disk model for different values of

and of the local thrust coefficient

(where

is the static pressure jump across the disk and

is the free stream velocity).

Figure 2 shows the dimensionless axial velocity at the disk with and without the hub (

where the

is used to denote a dimensionless quantity), and the relative percentage difference

.

The analysis was carried out for

, and

and for two different values of

, i.e., 0.25 and 0.04, which are representative of a small- and a large-sized wind rotor, respectively. Inspecting

Figure 2, it clearly shows that the hub blockage rapidly drops to zero in the

case, and it is generally small. Conversely, for

, the hub presence leads to a significant discrepancy in comparison with the no-hub case all along the blade span. Thus, for small-sized rotors, the hub presence may significantly affect the prediction accuracy of both local (flow angles and blade forces) and global (power coefficient) quantities. Therefore, in this case, the hub blockage effects should always be properly taken into account.

The aim of this paper is precisely the development of a correction factor for the hub blockage effects, which can be easily included in the existing classical BE/M-T algorithm without modifying its popular and successful formulation. The new procedure relies on the quantitative evaluation of the radial distribution of the axial velocity induced by the bare hub. In other words, it is assumed that this velocity is scarcely influenced by the value of the rotor load, an hypothesis that can be easily accepted by perusing

Figure 2. The validity and accuracy of the modified BE/M-T model are tested by comparing its results with those of a more advanced CFD-actuator-disk (CFD-AD) approach, which naturally and duly takes into account the hub blockage, the rotor presence, and the wake divergence and rotation.

In the next two sections, the main theoretical and practical details of the new approach are briefly described. Then, the reference method (CFD-AD) and the BE/M-T algorithm (in its classical version without the hub blockage effects correction) are validated against the experimental data of the MEXICO wind turbine [

19]. Finally, in the last section, the results of the modified BE/M-T model are discussed and compared with those of the CFD-AD.

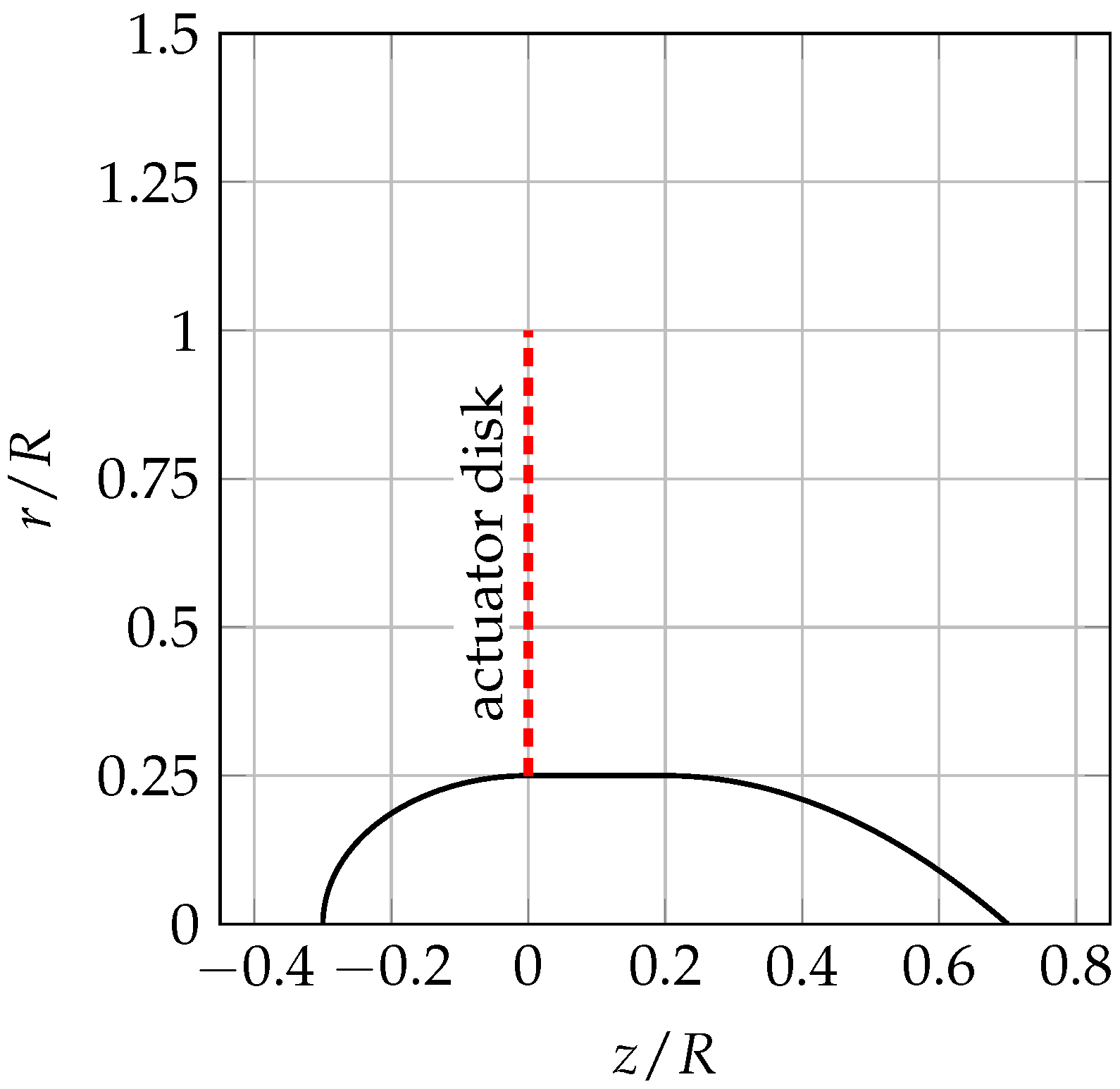

2. The Hub Blockage Factor

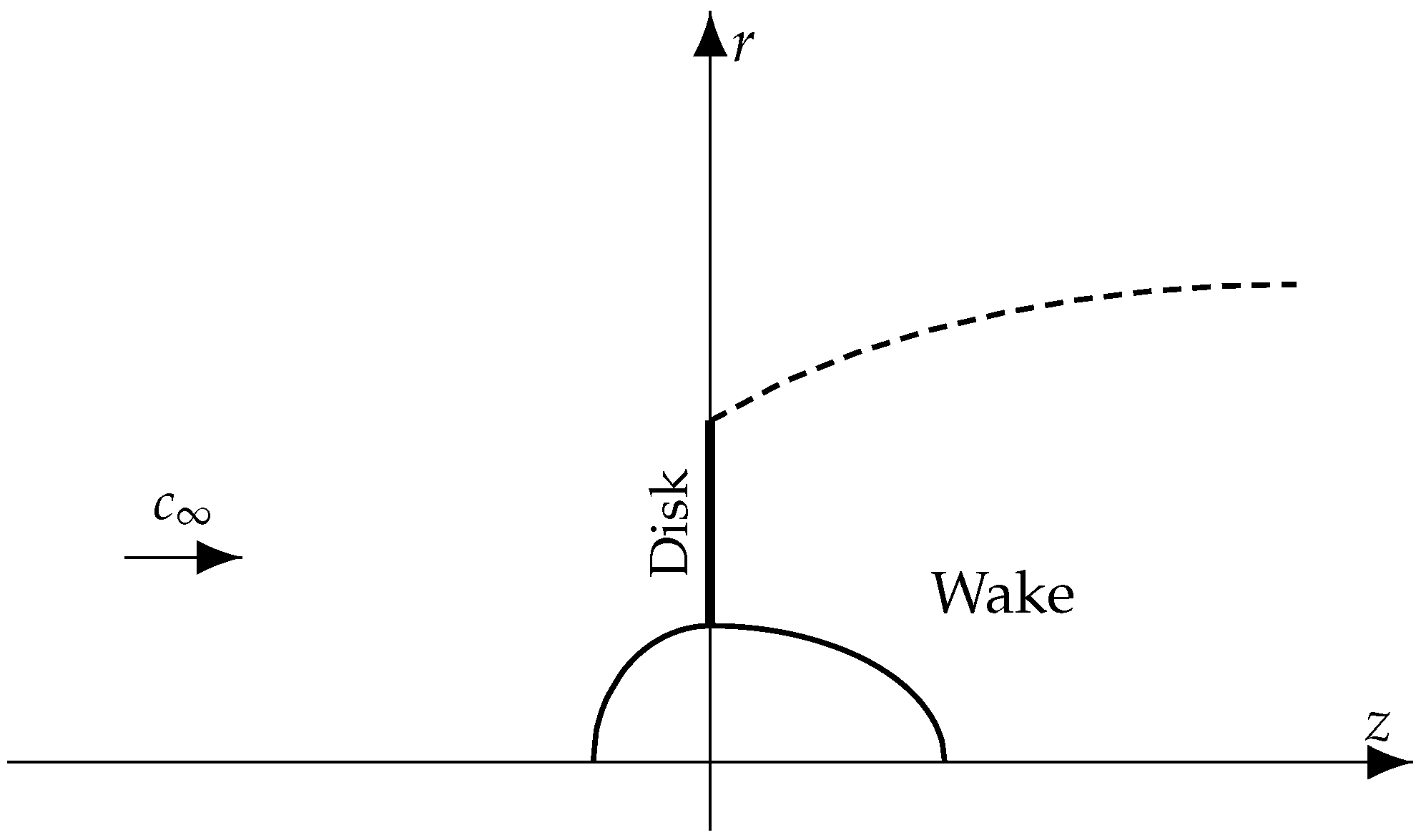

In the MT, the flow is supposed to be stationary, incompressible, inviscid, and axisymmetric. Consequently, we introduce a cylindrical coordinate system

, where the axial, radial, and tangential velocities are named

,

, and

, respectively (see

Figure 3).

At upstream infinity, the velocity and the static pressure are uniform, while a subscript is used for quantities at the actuator disk plane. In particular, the axial and radial velocities are uniform passing through the disk, whereas to simulate the presence of the turbine, jumps in the static pressure and the tangential velocity exist across the disk. Furthermore, it is also convenient to introduce the axial and tangential induction factors defined as and , where is the rotor angular velocity and is the flow tangential velocity just behind the disk. In the wake, a subscript w is used for those quantities evaluated at downstream infinity, where the flow is supposed to be fully developed in the axial direction and the radial component of the velocity is zero.

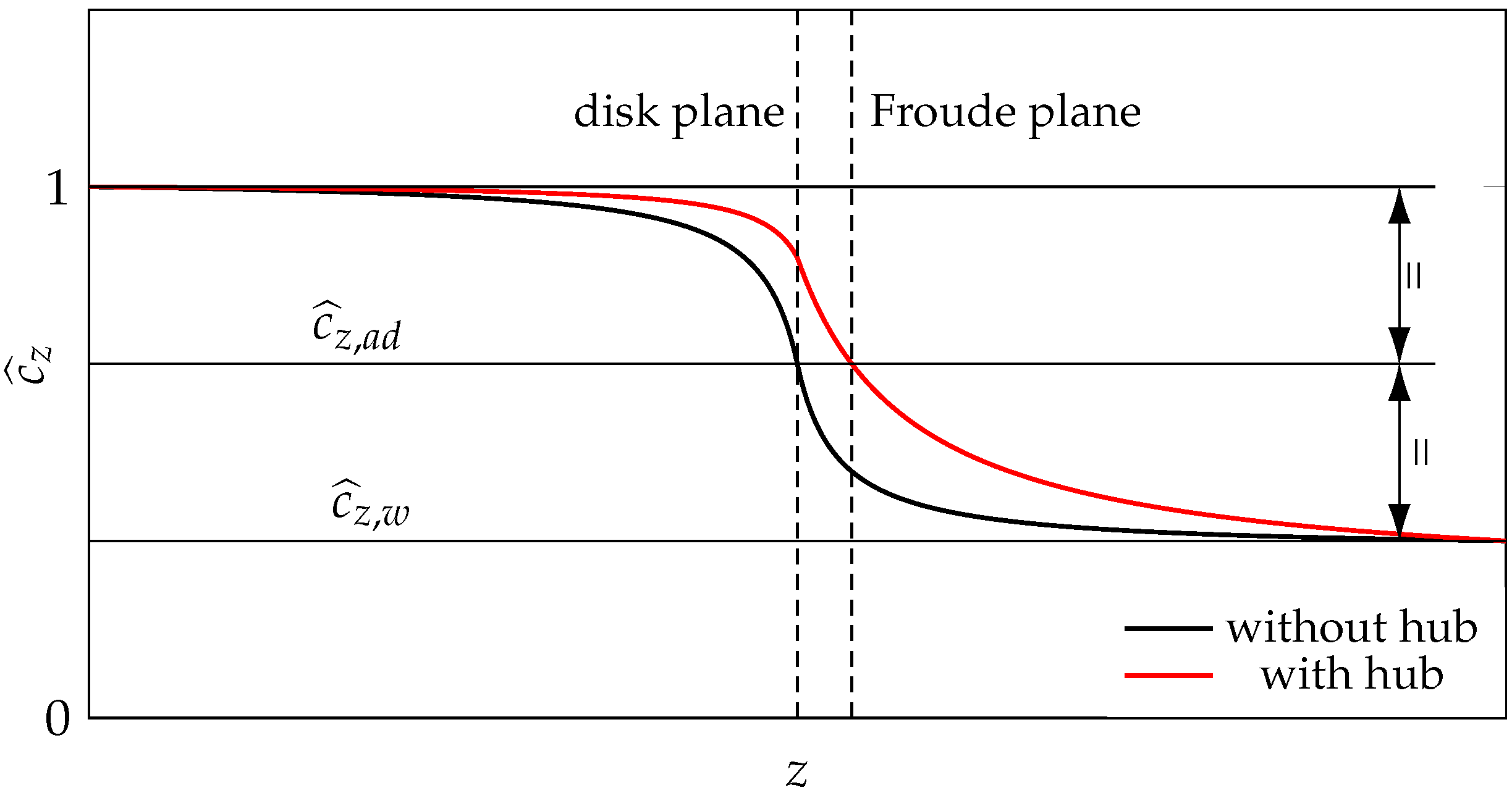

By further disregarding the wake divergence effect and linearising the wake rotation terms, it can be proven [

1] that the disk velocity is the arithmetic mean between the velocity values at up- and downstream infinity, i.e., in dimensionless form

. Since this equation is known as the Froude law, the plane where the axial velocity equals the mean between

and

is named the Froude plane. Therefore, the Froude and the disk planes coincide in the hubless case.

If the hub is taken into account, its blockage induces an increase in the axial velocity at the disk (see

Figure 4) where the Froude law is no longer valid.

Consequently, the Froude plane is shifted downstream of the disk by the hub blockage, and, by definition, the axial velocity and induction factor there read

where the subscript

is used to denote flow quantities evaluated at the Froude plane. Coupling the above two equations, it is easy to prove that

Having said that, the hub blockage factor

is defined as

that is, the ratio between the actual axial disk velocity (

) and its value when the hub is not considered (

). It is now assumed that

is the superposition of the velocities

associated with the sole disk (in the hubless case) and

induced by the bare hub (the hub without the disk) at the disk plane, that is,

With the above hypothesis, the mutual interaction between the hub- and disk-induced flow fields is neglected. In other words, the model assumes that at the disk plane, the velocity induced by the sole hub is not influenced by the disk presence and that the one induced by the sole disk is slightly affected by the hub. A quantification of the validity of this assumption can be inferred from

Figure 2 (bottom), which shows that the differences in the disk axial velocity between the cases with and without the hub are marginally influenced by the value of the rotor load, that is, by the disk presence.

The radial distribution of the velocity induced by the bare hub

depends upon the hub geometry and the operating conditions. It has to be externally evaluated and, successively, provided as input to the modified BE/M-T approach. A simple CFD simulation of the bare hub, a faster axisymmetric panel code (see, for example, Lewis [

20] and Bontempo and Manna [

18,

21]), or an experimental campaign can be used to evaluate

. Note that this is not the only externally provided data in the BE/M-T. Indeed, the experimentally or numerically evaluated characteristic curves of the blade profiles are also needed.

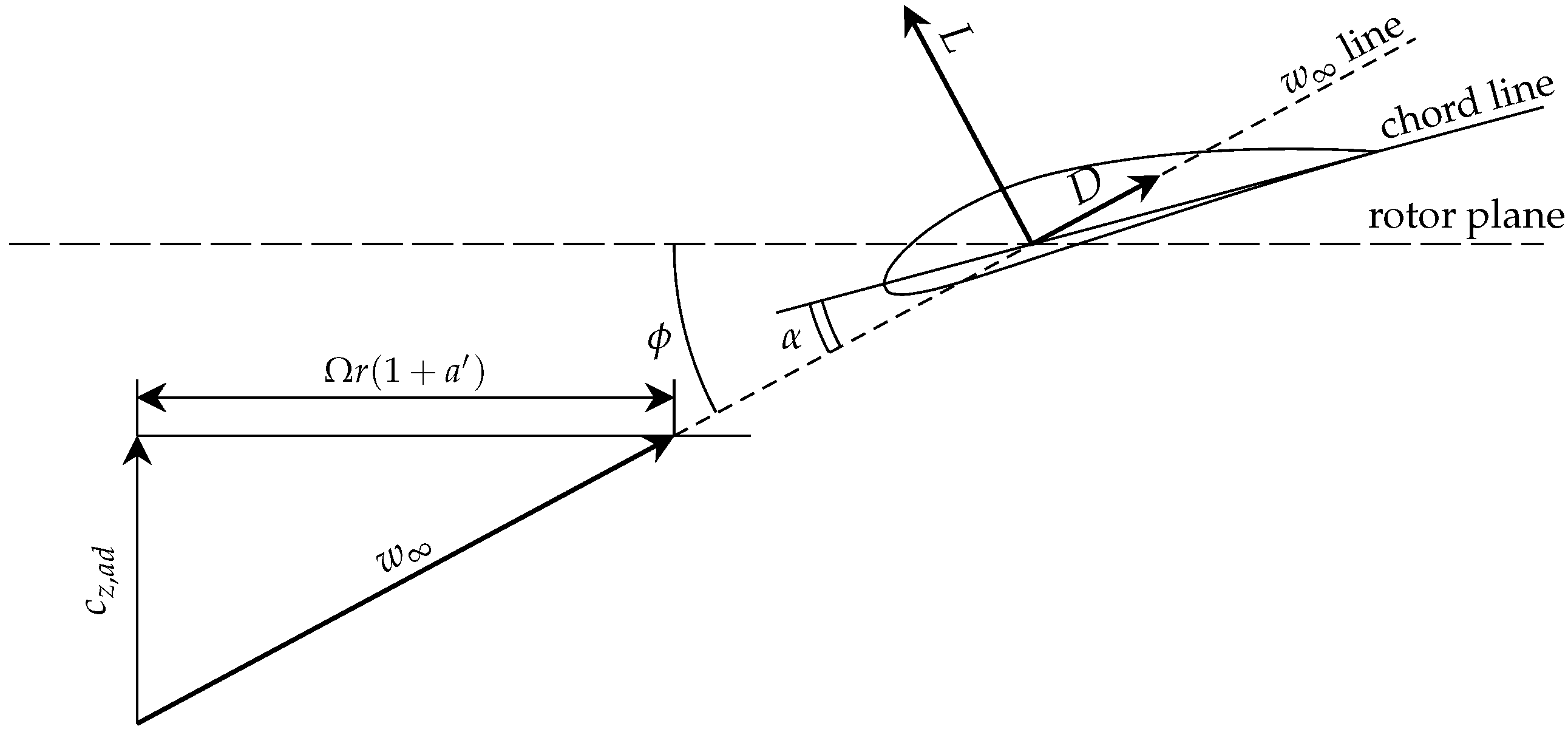

3. Formulation of the Blade-Element/Momentum Theory with the Hub Blockage Factor

In the BET, the blade is divided into

N elements whose radial length is

, and then a simple force decomposition strategy (see

Figure 5) leads to the following equations for the thrust

and the torque

exerted on the elements:

In the above equation,

Z is the blade count,

is the fluid density,

is magnitude of the vectorial mean between the relative velocities at the inlet and outlet of the disk,

and

are the lift and drag sectional lift coefficients,

l is the chord of the blade element,

is the local solidity, and

is the tip correction proposed by Shen et al. [

8]. Moreover,

and

, while the flow angle

can be evaluated as (see

Figure 5)

In the above equation, is the local speed ratio.

With the help of the definitions of the axial induction factor (

1) and of the hub blockage factor (

4), Equations (

5)–(

7) become

which are the new versions of the BET equations corrected for the hub blockage.

Coming now to the MT equations, the elemental thrust is also obtained by applying the Bernoulli principle from upstream infinity to the disk, as well as from the disk to downstream infinity. Summing up the two equations returns

where, as is customary in the generalised MT, the wake rotation terms are linearised. Then, the elemental thrust

can be cast in the following classical form:

In the above equation, the factor

F is given by the product of the Prandtl’s expressions for the hub and tip correction factors associated with the effects of the finite number of blades [

22]. Then, substituting Equation (

2), the thrust

becomes

Finally, applying the angular momentum equation, the torque

can be cast in the following form:

The expressions for the axial

(resp., tangential

) induction factor originate from coupling Equations (

13) and (

8) (resp., (

14) and (

9)). Then, with some straightforward algebra, the following equations are obtained:

It is noteworthy that these equations are formally identical to those of the classical BE/M-T [

6] when

is used in lieu of

a and

is introduced. Thus, it is not surprising that the iterative solution algorithm of the modified BE/M-T model is almost the same as its classical counterpart. Specifically, the operating conditions, the blade geometry (radial distribution of the chord and pitch angle), the characteristic curves of the 2D blade sections, and the radial distribution of the externally computed hub-induced-velocity

are given as input data. Then, for each blade element, an initial value for

and

is guessed, and

is evaluated via Equation (

4). Successively, Equation (

10) returns the flow angle

, and the correction factors

F and

are readily evaluated, as well as the angle of attack

(see

Figure 5). At this point,

and

are obtained from the characteristic curves of the 2D blade sections, and the coefficients

and

are computed. Finally, the

and

values are updated through Equations (

15) and (

16), and the loop is repeated until convergence.

Due to the insurgence of the turbulent-wake-flow regime, Equation (

13) has to be replaced by an empirical correction formula when the axial induction factor exceeds a prescribed critical value (e.g., 0.3–0.4). As already discussed in the Introduction, several empirical corrections exist, and all of these can be modified to include the hub blockage effect. However, for the sake of brevity, only the [

10] formula is described here. In this approach, a quadratic relation between the thrust coefficient and the axial induction factor is used when this latter quantity exceeds the critical value of 0.4. The parameters of the quadratic function are evaluated also, requiring a smooth fitting with the thrust equation of the MT. Taking into account the hub presence, the same procedure (based on a smooth fitting at

with the modified Equation (

13)) leads to the following form of the revised Buhl [

10] correction:

Coupling Equations (

8) and (

17), the new

expression becomes

to be used in lieu of Equation (

15) when

.

4. Validation of the Modified BE/M-T and of the CFD-AD Method

A home-made BE/M-T code, developed in Fortran 2003, is used as a basis to introduce the hub blockage factor

. The software can deal with different updating strategies for the induction factors [

8], as well as with several empirical corrections for highly loaded cases. However, as previously discussed, in this paper only the classical approach by Glauert [

1] along with the Buhl [

10] formula are used.

To validate the numerical procedure, the experimental data of the three-bladed 4.5 m diameter MEXICO wind turbine are chosen [

19]. This is because the full geometry of the hub is completely available for this turbine. The blade geometry is made up of a cylindrical root and three different airfoil types, viz. DU91-W2-250, RIS∅ A1-21, and NACA 64-418, along with three transition zones between them. The characteristic curves of the three blade sections provided by Schepers et al. [

19] are used, while a weighted mean of these curves is used in the transition regions. The

induced by the bare hub is evaluated (see

Figure 6) via an axisymmetric simulation carried out employing the pressure-based solver included in the commercial CFD package ANSYS Fluent R24.1. In particular, the pressure–velocity coupling is performed through the well-known SIMPLE segregated algorithm [

23], and the QUICK [

24] scheme is employed for the spatial discretisation. The turbulence closure is obtained via the

RNG model proposed by Orszag et al. [

25], while an enhanced wall treatment for the

-equation is adopted as the near-wall modelling method [

26]. A grid convergence study and more details on the computational settings are available in [

21].

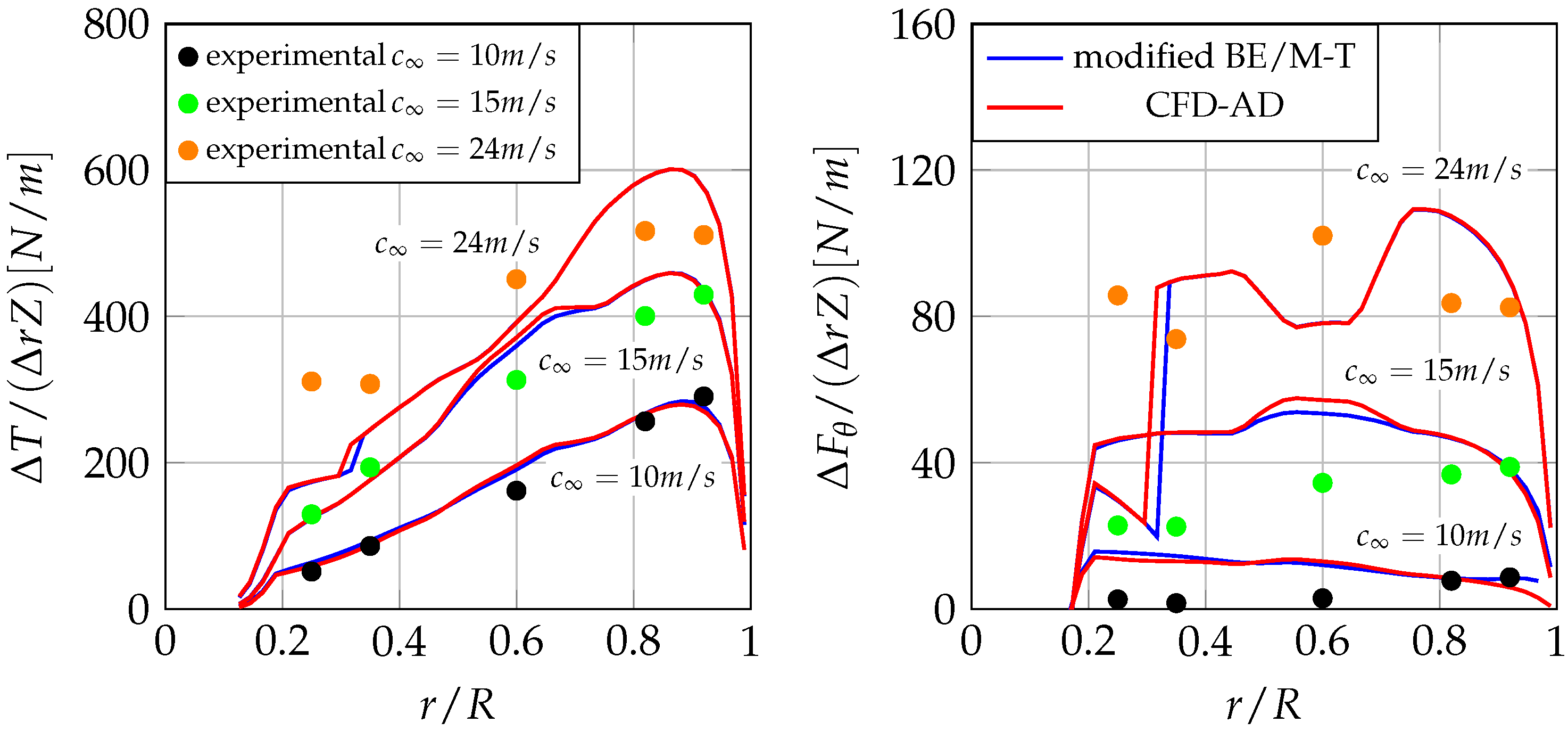

The MEXICO turbine is operated at a fixed value for the revolution speed (424.5 rpm) and pitch angle (

), while the data are available at

, and 24 m/s.

Figure 7 shows the radial distributions of the axial and tangential blade-force density of the modified BE/M-T code along with the experimental data.

Overall, the agreement is satisfactory, also in view of the fact that a similar accuracy level is obtained by the blind comparisons carried out with more advanced models (see Figures 8.6–8.7 in Schepers et al. [

19]). At high values of the wind speed, flow separation takes place all along the blade suction-side [

27], significant three-dimensional effects occur, and the predictivity of the BE/M-T code is lost.

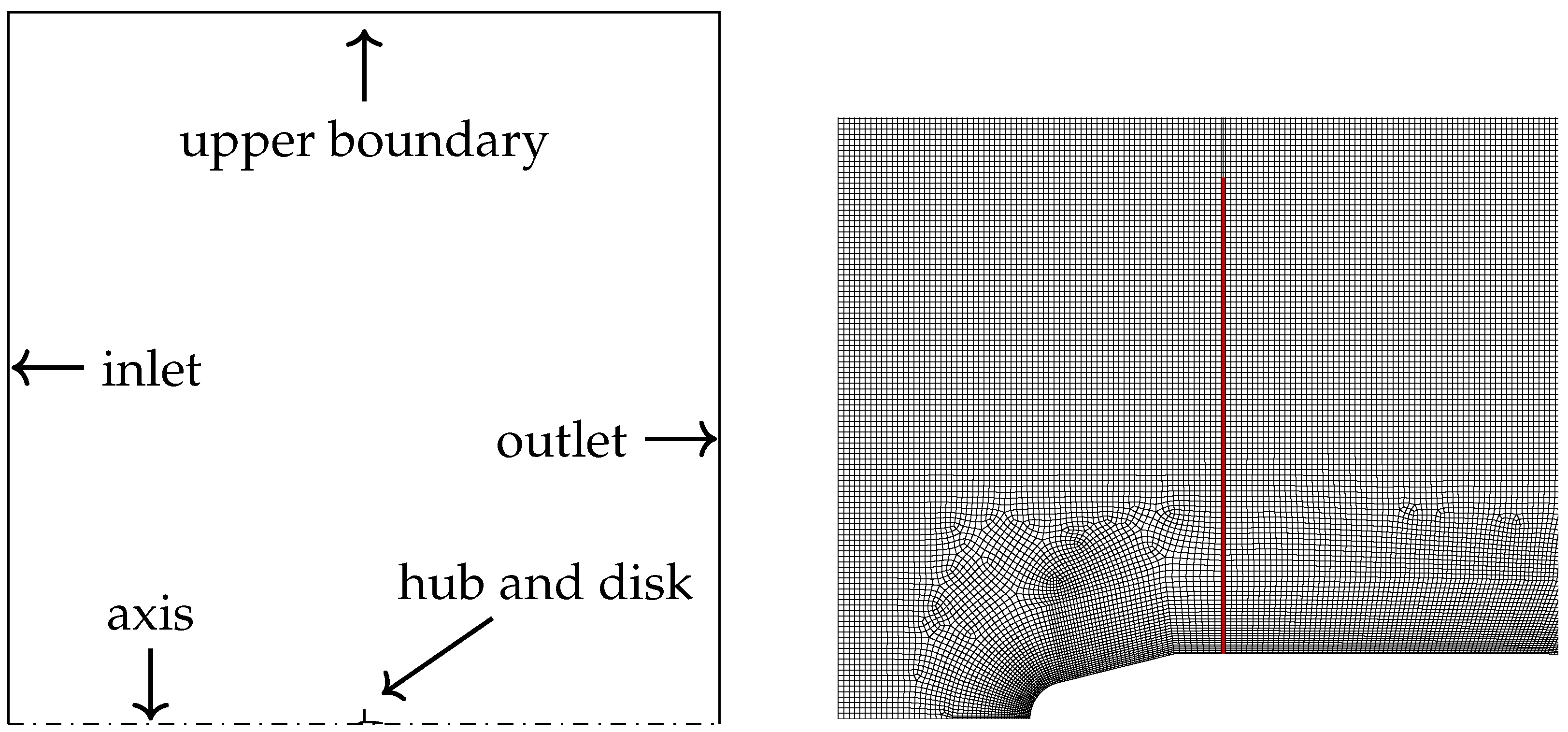

Due to the lack of available experimental data (including the blade and hub geometry) for small-sized wind turbines with a significant value of

, the validity of the proposed BE/M-T approach is tested (see the next section) against a reference method, namely, the so-called CFD-AD, which is adopted here because it fully and naturally takes into account the hub presence. In particular, the CFD-AD solves the steady, axisymmetric, and incompressible Euler equations by finite volume or difference schemes, whereas it models the turbine effects by a set of body forces distributed over the disk. To this aim, the axial and tangential source terms are activated only in the disk region, and, as in the BE/M-T, they are iteratively evaluated using a BET module. The latter is embedded in ANSYS Fluent via home-made Used Defined Functions (see [

2] for a complete description and [

28] for a thorough grid convergence analysis). For the sake of clarity,

Figure 8 shows the computational domain, the boundary conditions, and a close-up view of the mesh in the hub–nose proximity.

The numerical set-up previously described for the evaluation of

is used in the CFD-AD, too.

Figure 7 also shows the radial distributions of the axial and tangential blade-force densities obtained through the CFD-AD. Overall, as for the BE/M-T, the agreement can be considered satisfactory, especially for low to moderate values of the wind speed.

5. Analysis of the Results for a Small Wind Turbine with a High Hub Blockage

In the previous section, the results of the modified BE/M-T were analysed and compared with the experimental data, as well as with those of the CFD-AD. Although a good agreement was found, this study cannot be considered conclusive. In fact, due to the low

value (0.12) of the MEXICO rotor, the hub did not induce a significant blockage effect (see also

Figure 6). Therefore, in this section, a more meaningful analysis is carried out using a three-bladed 1 m diameter small wind turbine with a high

value, which, according to

Figure 1, is set to 0.25. To this aim, a simple hub geometry parametrisation is used. The fore part of the hub is half of an ellipsoid whose dimensionless axial length is 0.3. The central part of the hub is a right-circular cylinder with an axial length equal to 0.2, while the rear part of the hub has a parabolic shape with the vertex located at the end of the cylinder (see

Figure 9).

The hub has a unit total dimensionless length, while the disk is located between the ogive and the cylindrical part. The blade chord and twist distributions are evaluated via the classical Glauert optimum-rotor model [

6], adopting a design value for the tip speed ratio equal to 7. The low Reynolds SG6043 [

29] airfoil is used all along the blade, while the root has a cylindrical shape with a transition zone. Finally, it should be stressed that the structural design of the turbine blade is out of the scope of this paper, and for this reason, it is not considered herein.

The analysis compares the results of the CFD-AD method with those of the BE/M-T algorithm with and without the correction for the hub blockage. Obviously, the investigation is carried out using the same characteristic curves of the blade sections, as well as the same form of the tip and hub correction factors for the finite number of blades. The evaluation of the hub-induced velocity

(reported in

Figure 6) is carried out using the numerical procedure described in the previous section.

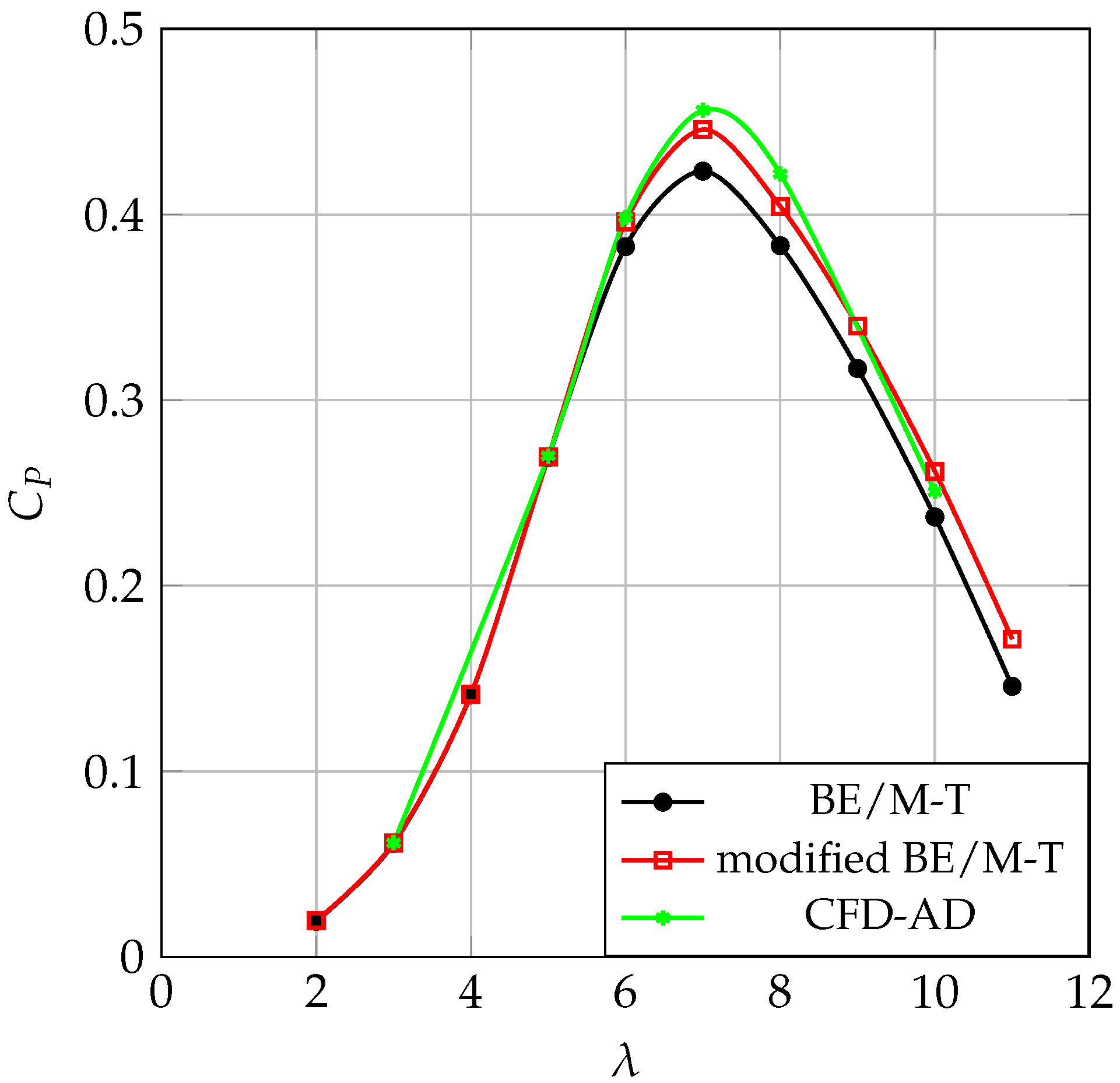

Figure 10 shows the power coefficient

(where

P is the power) as a function of the tip speed ratio

.

The differences between the results of the CFD-AD and the BE/M-T without the correction for the hub blockage are significant, thus proving that, contrarily to the MEXICO rotor, this is a challenging case where the hub presence should be taken into account (see also

Figure 6 for a comparison of the

velocity induced in the two cases). The same conclusion can be inferred by perusing

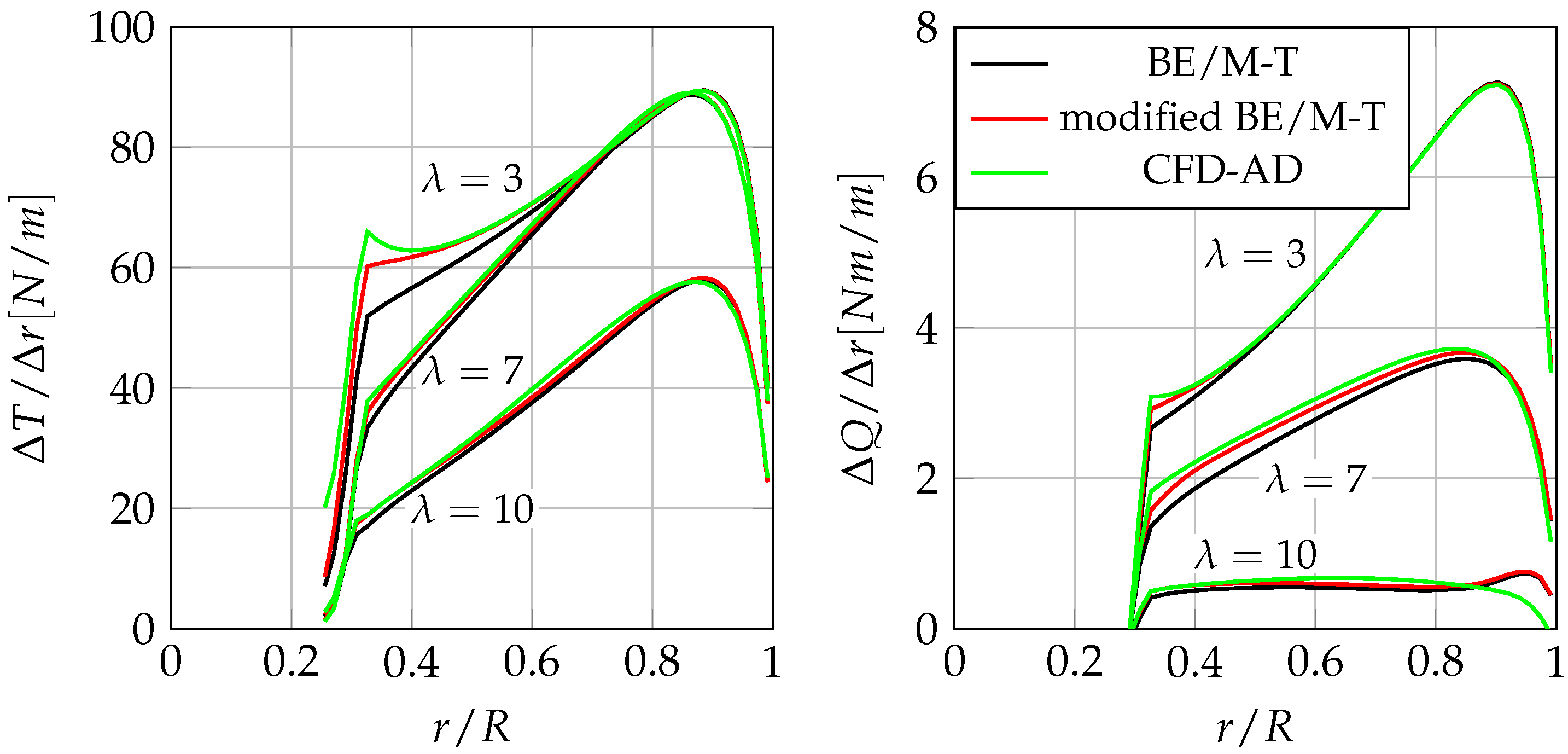

Figure 11, which shows the radial distribution of the thrust and torque per unit length.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 also show that, introducing the proposed correction for the hub blockage, the differences between the CFD-AD and the BE/M-T considerably reduce for all

values, especially in the hub proximity. This proves the reliability and accuracy of the present correction strategy, even for a very challenging case characterised by a considerably large value of the ratio between the hub and rotor radius (

).

Figure 11 also points out that the discrepancy between the CFD-AD and the BE/M-T results, especially in terms of

, is significant for low

values and becomes negligible when

is high. This can be explained by analysing the shape of the velocity triangles. For high

values, the inlet velocity triangle has a very high aspect ratio, namely, the height of the triangle (

) is very small in comparison with its basis (

). Therefore, the

increase, associated with the hub presence, only marginally changes the

direction, the angle of attack, and, consequently, the blade force. Contrariwise, for low

values, the aspect ratio of the inlet velocity triangle reduces so that the hub blockage induces a significant variation in the angle of attack and blade forces. As shown in

Figure 11, the proposed model significantly mitigates the differences with the CFD-AD results also for low

values, where the hub blockage induces remarkable changes in the blade forces.

Finally, it is important to note that the discrepancies between the CFD-AD and the BE/M-T approaches are not exclusively associated with the hub presence, but other differences, which cannot be removed, exist. In fact, unlike the CFD-AD, the MT disregards the wake divergence effects and it linearises the swirl velocity terms. Moreover, the application of the Prandtl correction factors also differs between the two approaches.

6. Conclusions

This paper has presented a new correction factor to be included in the BE/M-T capable of accounting for the effect of the hub presence. This correction is of particular importance for small-sized wind turbines whose ratios between the hub and rotor radii values up to 25–30%.

The hub presence induces an increase in the axial velocity at the disk, and the Froude plane, defined as the axial station where the velocity is the arithmetic mean between the axial velocities at up- and downstream infinity, is shifted downstream of the disk. For this reason, a hub blockage correction factor has been defined as the ratio between the actual axial disk velocity () and its value at the Froude plane (). Then, neglecting the mutual interaction between the flow fields induced by the hub and the disk, the BE/M-T has been reformulated in such a way that the new equations are formally identical to those of the classical BE/M-T when is used in lieu of a and is introduced. By doing so, the proposed approach gives the indisputable advantage of a straightforward and easy implementation of an effective correction factor into already existing BE/M-T codes.

The validity and accuracy of the modified BE/M-T model are tested by comparing its results with those of a more advanced CFD-AD approach which naturally and duly takes into account the hub blockage, the rotor presence, and the wake divergence and rotation.

The comparison has been carried out for two cases. The first one is the MEXICO rotor, characterised by a moderate value of the ratio between the hub and rotor radii (). For this case, the availability of experimental data also allowed a validation of the method. The second case is a more meaningful configuration, that is, a small-sized wind turbine with . In both cases, the results obtained via the proposed correction strategy for the hub blockage have shown good accuracy. Specifically, a significant reduction in the discrepancies occurring against the results of the reference method (CFD-AD) in terms of both global (power coefficient) and local (thrust and torque per unit length) quantities has been reported.