Liquid Droplet Breakup Mechanisms During the Aero-Engine Compressor Washing Process †

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of the Paper and Novelty

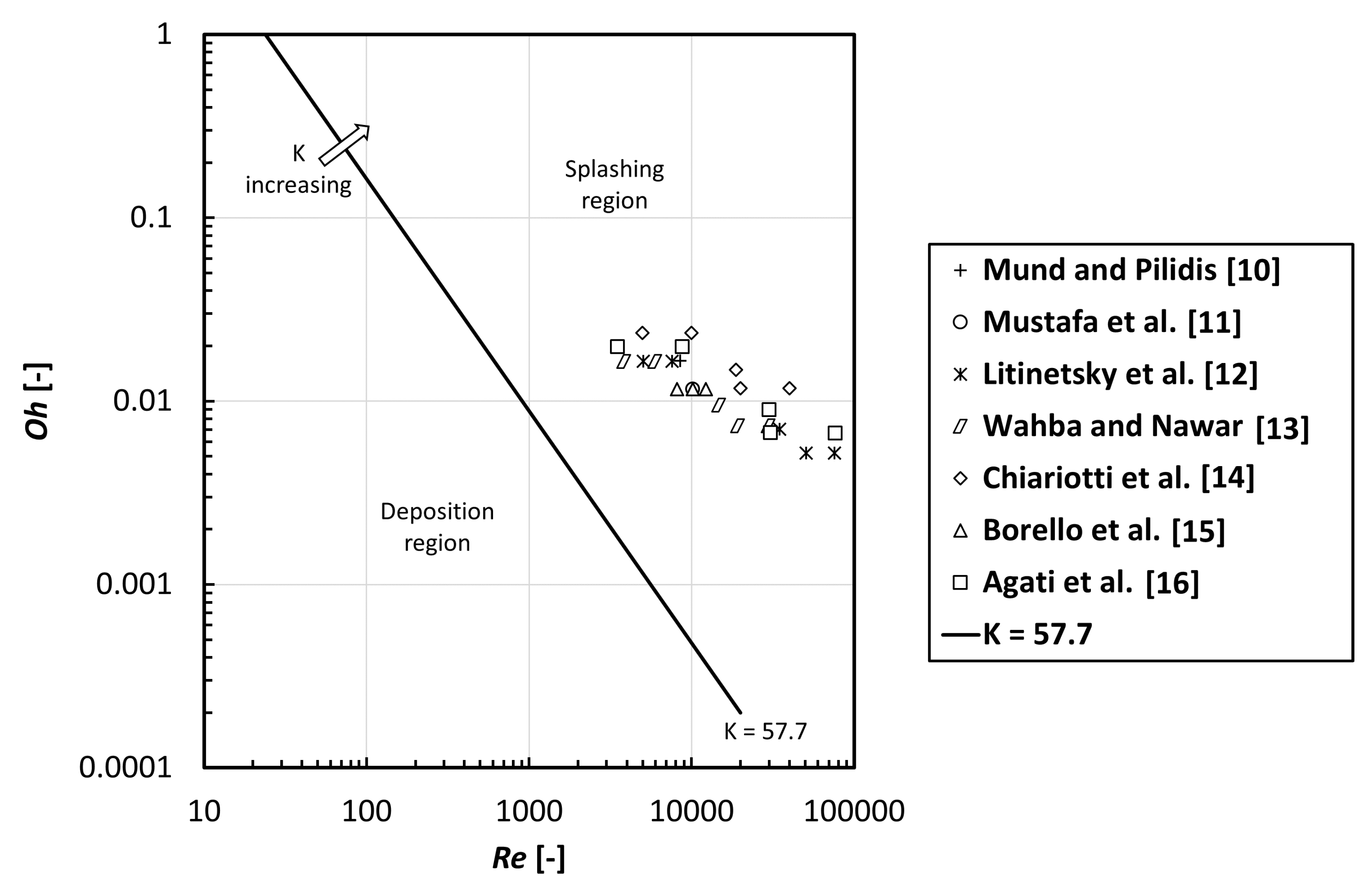

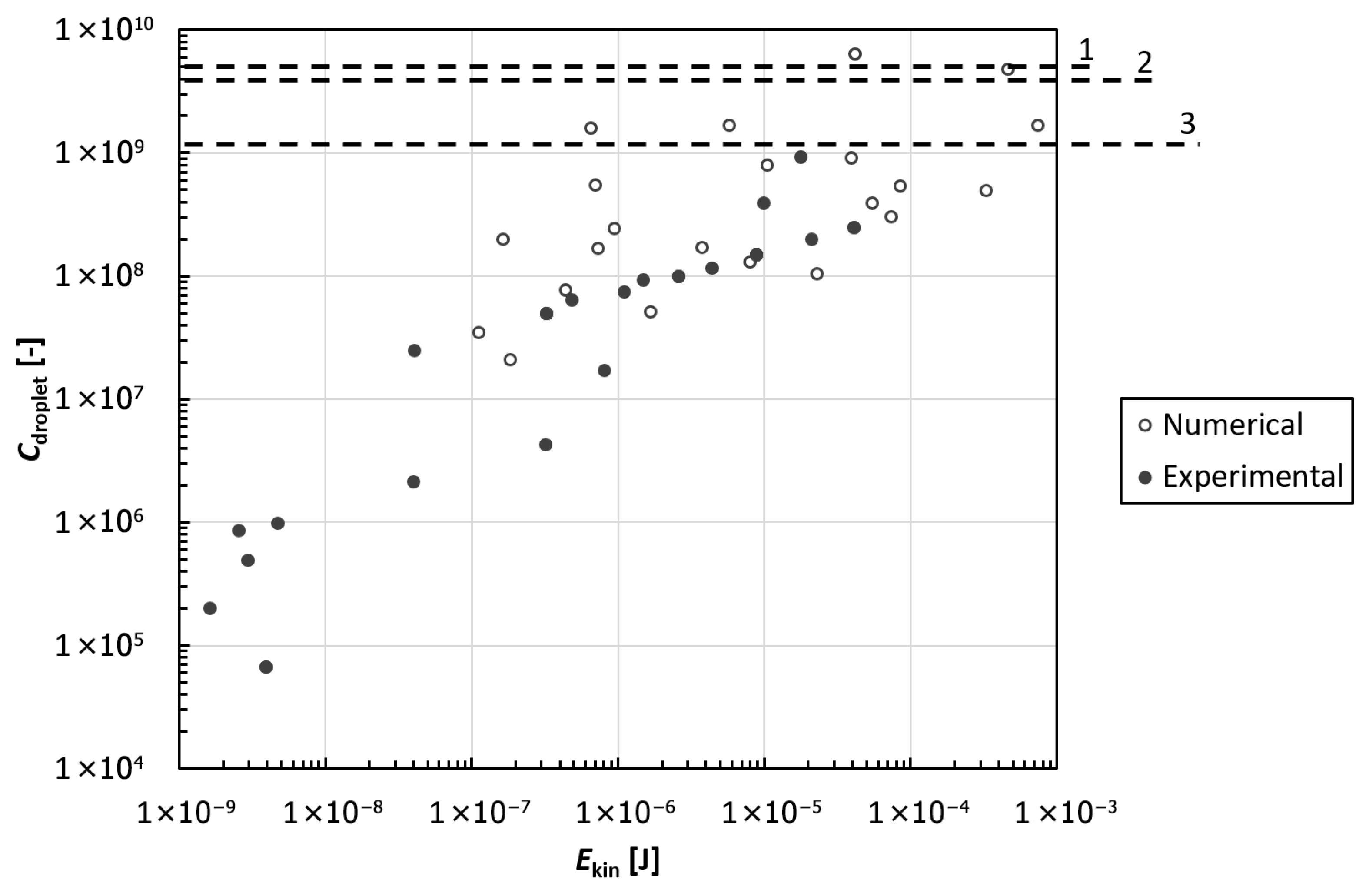

2. Literature Database

3. Droplet Breakup Mechanisms

3.1. Primary Breakup Mechanism

- The vibrational breakup occurs for lower Weber number values (). The flow interacts with the droplet and produces a vibration of natural amplitude. The flow amplifies the oscillation, driving the droplet to breakup and forming large fragments.

- The bag breakup occurs for higher Weber numbers () and is characterized by forming a hollow bag in which a thin film of liquid is placed downstream of a more massive toroidal ring. The bag breaks out at a specific instant, generating many small fragments.

- The bag and stamen breakup is a transition mechanism with characteristics common to the bag breakup with .

- Sheet stripping() distinctly differs from the two rupture mechanisms discussed. No bags are formed, but a thin sheet of liquid forms on the peripheral circumference of the deformed droplet, from which droplets are continuously stripped.

- For higher Weber numbers (), waves of large amplitude but small wavelengths are formed on the surface of the windward droplet. The action of the flow on itself continuously erodes the crests of the waves. This process is called wave crest stripping. For the largest Weber numbers, waves characterized by large amplitude and wavelength are formed on the droplet’s surface. This process is called catastrophic breakup. This leads to a multi-stage process in which fragments are subject to further breakup. This cascading process continues until each fragment reaches a critical value of the lower Weber number. Subsequently, the fragments are affected by the breakup mechanisms described above.

3.2. Secondary Breakup Mechanisms

3.2.1. Low Weber Number

3.2.2. Intermediate Weber Number

3.2.3. Higher Weber Number

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Blade parameter related to erosion [kg2 m−2 s−3] | |

| Droplet parameter related to erosion [kg2 m−2 s−3] | |

| Speed of sound | |

| Contact angle [°] | |

| D | Droplet diameter [m] |

| Kinetic energy [J] | |

| E | Elastic modulus [MPa] |

| Fracture toughness [MPa m1/2 | |

| K | Parameter related to droplet impact [-] |

| Ohnesorge number [-] | |

| Reynolds number [-] | |

| V | Velocity [m s−1] |

| Water-to-air ratio [%] | |

| Weber number [-] | |

| Surface tension [N m−1] | |

| Dynamic viscosity [Pa s] | |

| Density [kg m−3] | |

| Yield strength [MPa] |

References

- Suman, A.; Morini, M.; Aldi, N.; Casari, N.; Pinelli, M.; Spina, P.R. A compressor fouling review based on an historical survey of asme turbo expo papers. J. Turbomach. 2017, 139, 041005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, J.P. Gas turbine compressor washing state of the art: Field experiences. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2001, 123, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, R.; Brun, K. Fouling mechanisms in axial compressors. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2012, 134, 032401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mund, F.C.; Pilidis, P. Gas turbine compressor washing: Historical developments, trends and main design parameters for online systems. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2006, 128, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.E.; Medraj, M. Prediction and experimental evaluation of the threshold velocity in water droplet erosion. Mater. Des. 2022, 213, 110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, A.; Cordone, A.; Zanini, N.; Piovan, M.; Pinelli, M.; Koster, M.; Kuntzagk, S.; Weiler, H.; Werner-Spatz, C. Liquid Droplet Breakup Mechanisms During the Aero-Engine Compressor Washing Process. In Proceedings of the 16th European Turbomachinery Conference, Hannover, Germany, 24–28 March 2025; Available online: https://www.euroturbo.eu/29092025/publications/proceedings-papers/etc2025-319/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Brun, K.; Grimley, T.A.; Foiles, W.C.; Kurz, R. Experimental Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Online Water-Washing in Gas Turbine Compressors. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2015, 137, 042605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igie, U.; Pilidis, P.; Fouflias, D.; Ramsden, K.; Laskaridis, P. Industrial Gas Turbine Performance: Compressor Fouling and On-Line Washing. J. Turbomach. 2014, 136, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syverud, E.; Bakken, L.E. Online water wash tests of GE J85-13. J. Turbomach. 2007, 129, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mund, F.; Pilidis, P. Online compressor washing: A numerical survey of influencing parameters. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J. Power Energy 2005, 219, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.; Pilidis, P.; Amaral Teixeira, J.A.; Ahmad, K.A. CFD aerodynamic investigation of air-water trajectories on rotor-stator blade of an axial compressor for online washing. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2006: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Barcelona, Spain, 8–11 May 2006; pp. 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litinetsky, A.; Litinetski, V.; Hain, Y.; Gutman, A. Parametric study of on-line compressor washing systems using CFD analysis. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2008: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Berlin, Germany, 9–13 June 2008; pp. 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, E.; Nawar, H. Multiphase flow modeling and optimization for online wash systems of gas turbines. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 7549–7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiariotti, A.; Borello, D.; Venturini, P.; Costagliola, S.; Gabriele, S. Erosion prediction of gas turbine compressor blades subjected to water washing process. In Proceedings of the Asia Turbomachinery & Pump Symposium, Singapore, 12–15 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Borello, D.; Venturini, P.; Gabriele, S.; Andreoli, M. New model to predict water droplets erosion based on erosion test curves: Application to on-line water washing of a compressor. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2019: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 17–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Venturini, P.; Gabriele, S.; Rispoli, F.; Borello, D. Effects of Water-to-Air Mass Ratio on Long-Term Washing Efficiency and Erosion Risk in an Axial Compressor Under Online Washing Conditions. J. Turbomach. 2024, 146, 051005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igie, U.; Pilidis, P.; Fouflias, D.; Ramsden, K.; Lambart, P. On-line compressor cascade washing for gas turbine performance investigation. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 Turbo Expo: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–10 June 2011; pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roupa, A.; Pilidis, P.; Allison, I.; Lambart, P. Study of wash fluid cleaning effectiveness on industrial gas turbine compressor foulants. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2013: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–7 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbadede, R.; Pilidis, P.; Igie, U.; Allison, I. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the influence of liquid droplet size on effectiveness of online compressor cleaning for industrial gas turbines. J. Energy Inst. 2015, 88, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casari, N.; Pinelli, M.; Spina, P.R.; Suman, A.; Vulpio, A. Performance degradation due to fouling and recovery after washing in a multistage test compressor. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2021, 143, 031020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulpio, A.; Suman, A.; Casari, N.; Pinelli, M.; Appleby, C.; Kyte, S. Washing effectiveness assessment of different cleaners on a small-scale multistage compressor. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2021: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Virtual, 7–11 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilch, M.; Erdman, C. Use of breakup time data and velocity history data to predict the maximum size of stable fragments for acceleration-induced breakup of a liquid drop. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1987, 13, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, A.; Casari, N.; Fabbri, E.; di Mare, L.; Montomoli, F.; Pinelli, M. Generalization of particle impact behavior in gas turbine via non-dimensional grouping. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 74, 103–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundo, C.; Sommerfeld, M.; Tropea, C. Droplet-wall collisions: Experimental studies of the deformation and breakup process. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1995, 21, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yi, X.; He, F.; Niu, F.; Hao, P. Effect of wettability on droplet impact: Spreading and splashing. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2021, 124, 110369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | D [µm] | V [m/s] | WTAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | 50 | 170 | 0.20 |

| [11] | 100 | 100 | 0.16 |

| [12] | 50–500 | 100–150 | 0.22 |

| [13] | 50–250 | 75–116 | 0.60 |

| [14] | 25–100 | 200–400 | - |

| [15] | 100 | 80–120 | - |

| [16] | 35–305 | 100–250 | 0.25–1.00 |

| Reference | D [µm] | V [m/s] | WTAR | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | 50–250 | 100 | - | R.V. |

| [9] | 25 | 100 | 0.43–3.00 | R.V. |

| [9] | 75 | 100 | 0.43–3.00 | R.V. |

| [9] | 200 | 100 | 0.43–3.00 | R.V. |

| [17] | 50–150 | 100 | 0.20 | - |

| [18] | 50–250 | 100 | 0.02 | - |

| [8] | 50–150 | 11–100 | 0.20 | Ma |

| [19] | 55.1–80.2 | 105 | - | - |

| [7] | 120 | 99–149 | 0.10–0.50 | Ma |

| [20] | 25 | 20–34 | 1.66–1.93 | - |

| [21] | 20 | 35 | 1.00–3.18 | - |

| [21] | 50 | 35 | 1.00–3.18 | - |

| [21] | 100 | 35 | 1.00–3.18 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the EUROTURBO. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zanini, N.; Suman, A.; Cordone, A.; Piovan, M.; Pinelli, M.; Kuntzagk, S.; Weiler, H.; Werner-Spatz, C. Liquid Droplet Breakup Mechanisms During the Aero-Engine Compressor Washing Process. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2025, 10, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp10040050

Zanini N, Suman A, Cordone A, Piovan M, Pinelli M, Kuntzagk S, Weiler H, Werner-Spatz C. Liquid Droplet Breakup Mechanisms During the Aero-Engine Compressor Washing Process. International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power. 2025; 10(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp10040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleZanini, Nicola, Alessio Suman, Andrea Cordone, Mattia Piovan, Michele Pinelli, Stefan Kuntzagk, Henrik Weiler, and Christian Werner-Spatz. 2025. "Liquid Droplet Breakup Mechanisms During the Aero-Engine Compressor Washing Process" International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power 10, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp10040050

APA StyleZanini, N., Suman, A., Cordone, A., Piovan, M., Pinelli, M., Kuntzagk, S., Weiler, H., & Werner-Spatz, C. (2025). Liquid Droplet Breakup Mechanisms During the Aero-Engine Compressor Washing Process. International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power, 10(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp10040050