An Experimental Investigation by Particle Image Velocimetry of the Active Flow Control of the Stall Inception of an Axial Compressor †

Abstract

1. Introduction

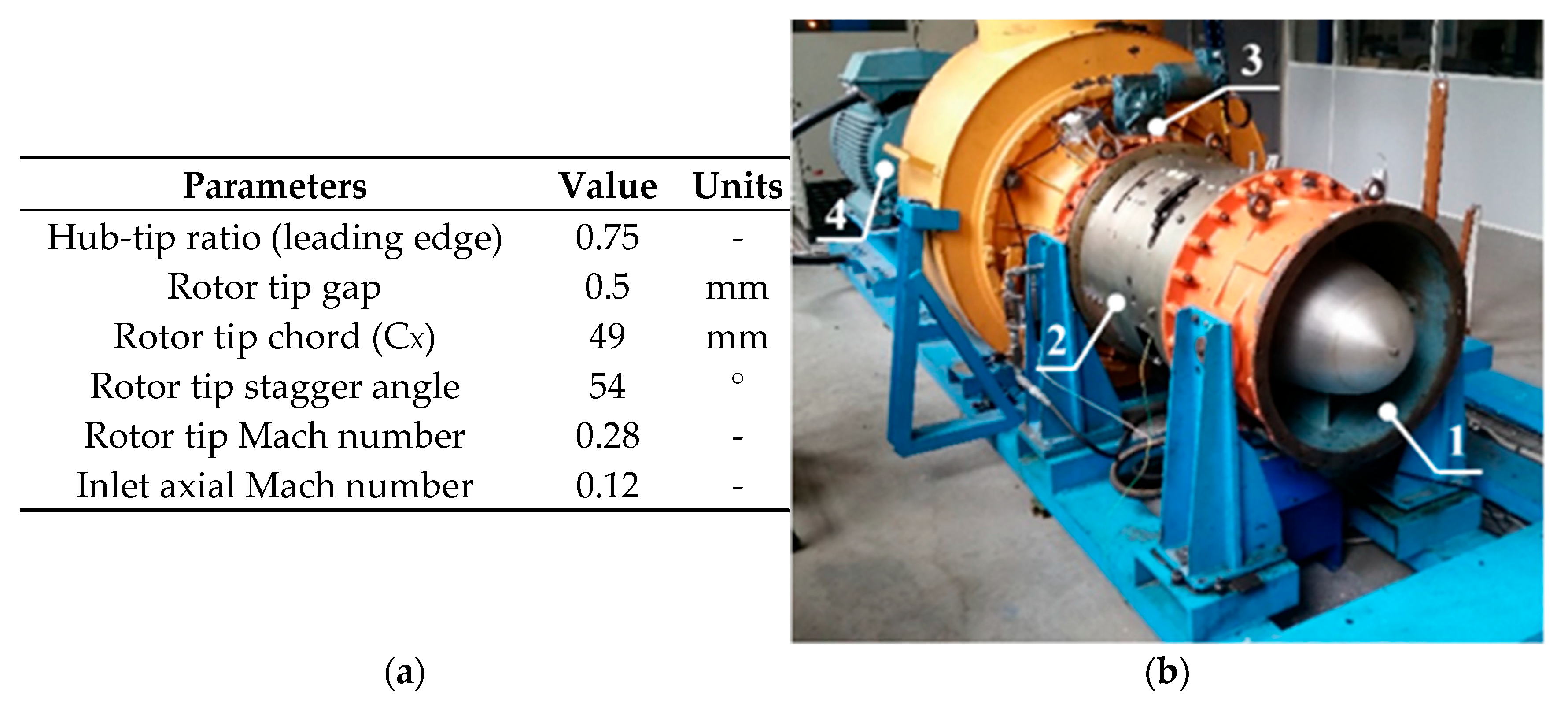

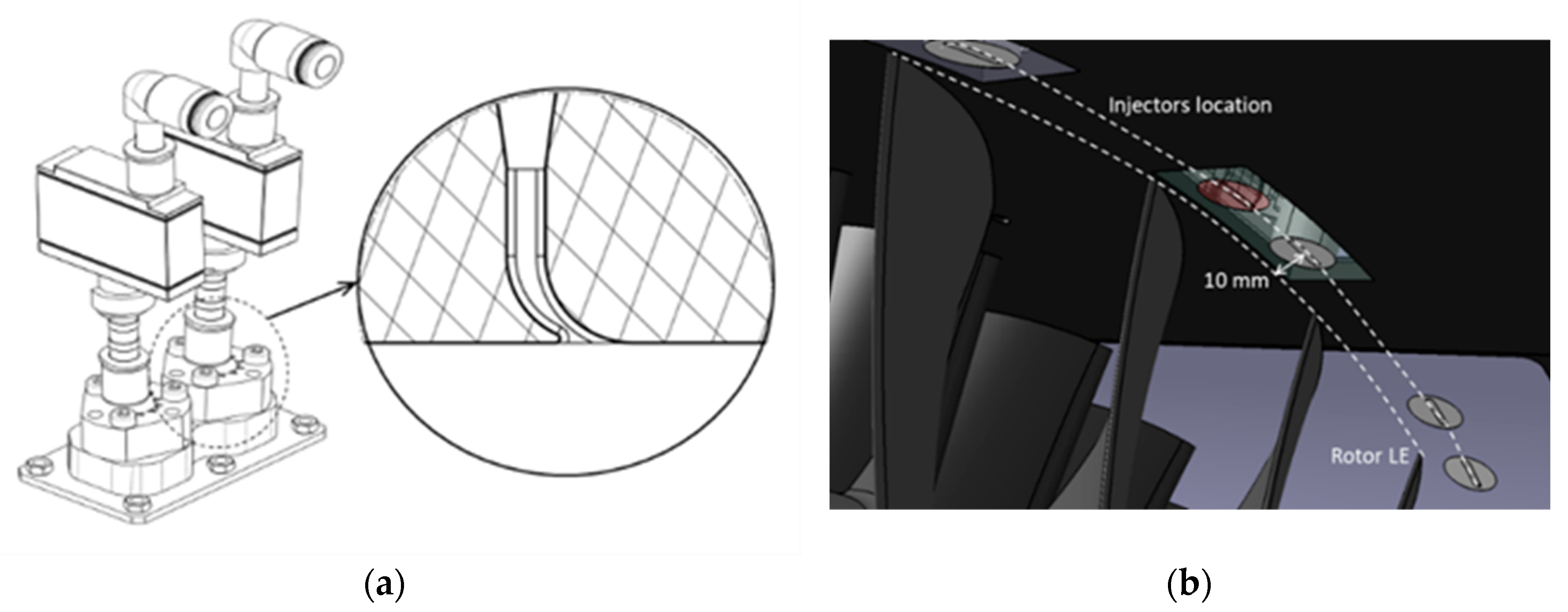

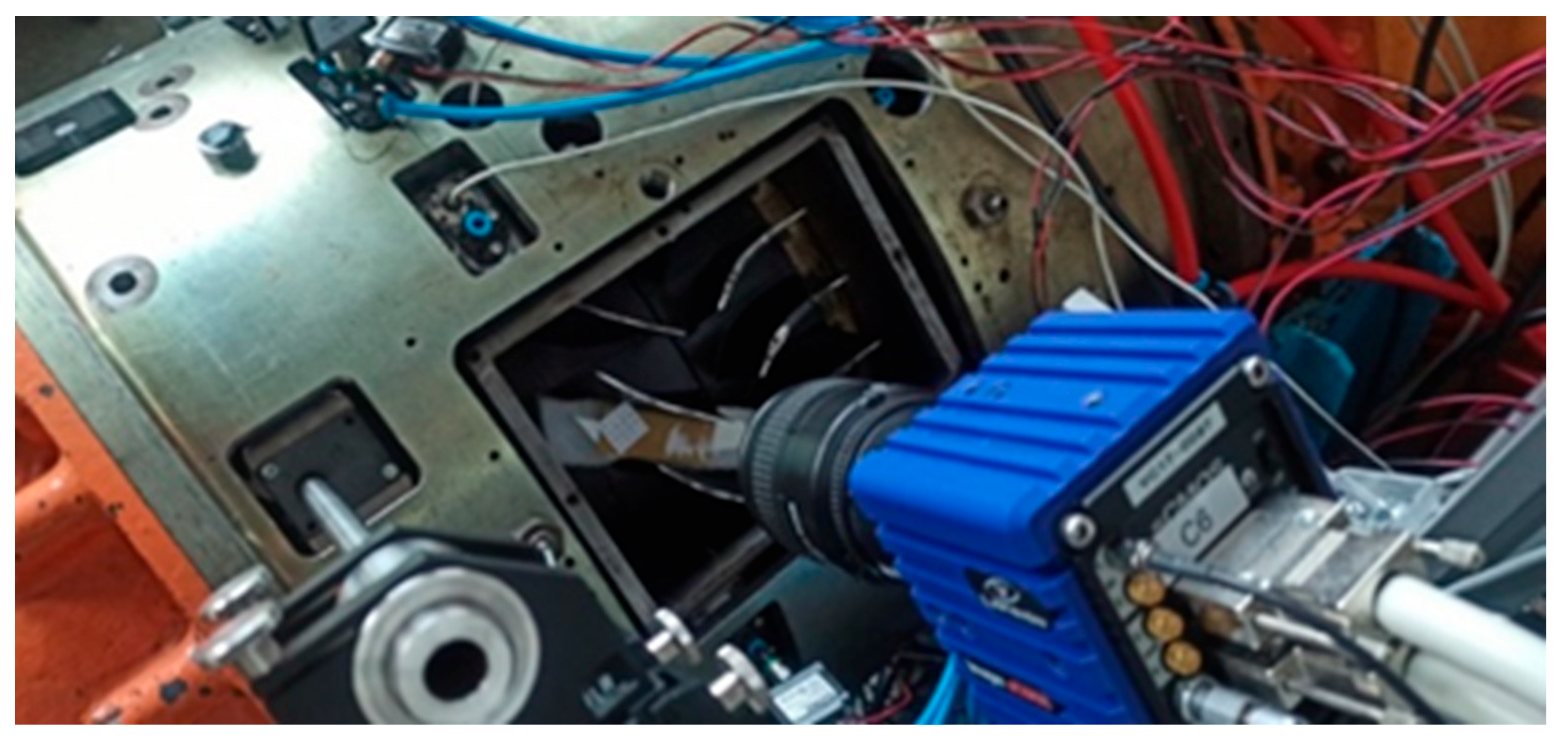

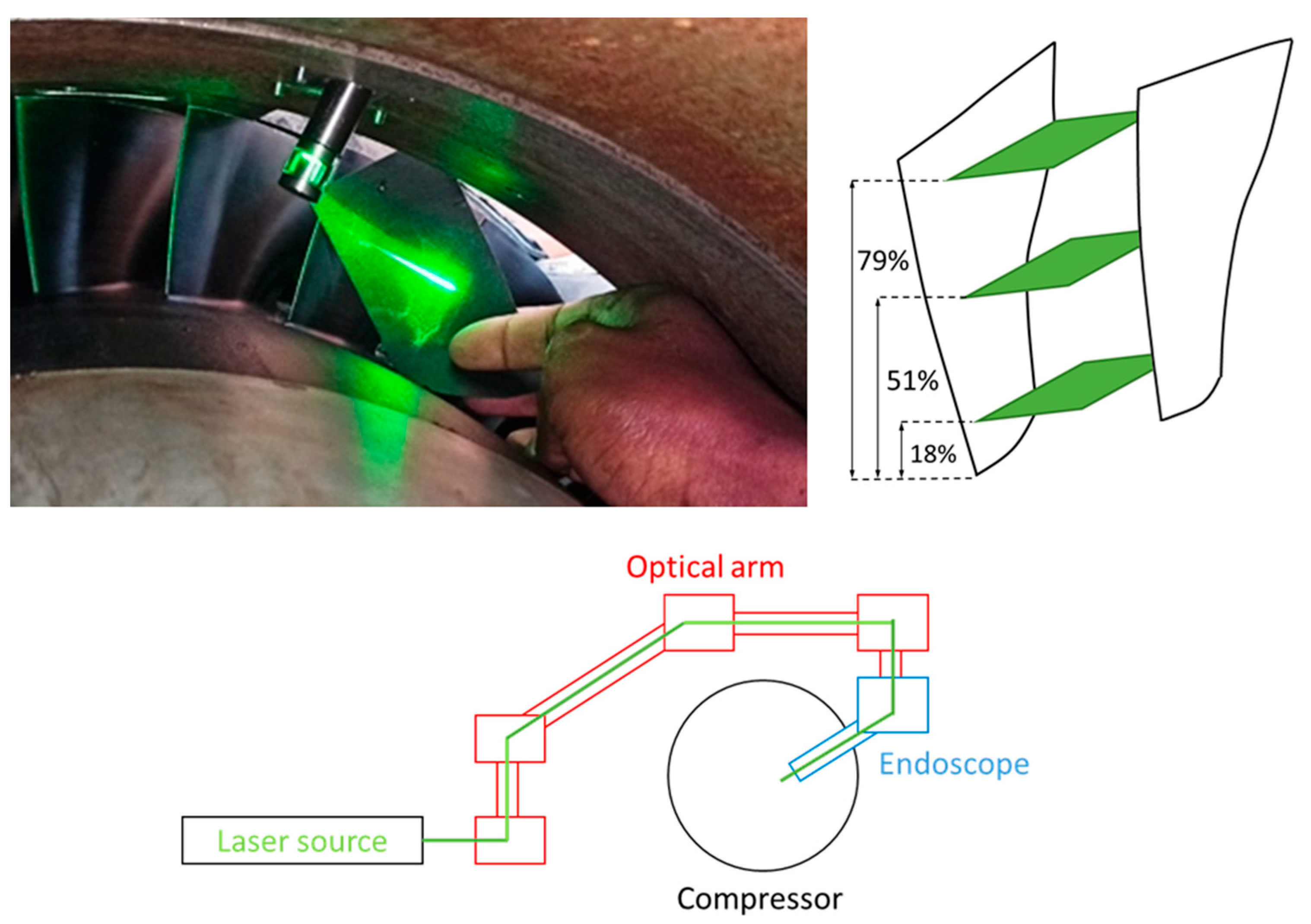

2. Experimental Setup

3. Results

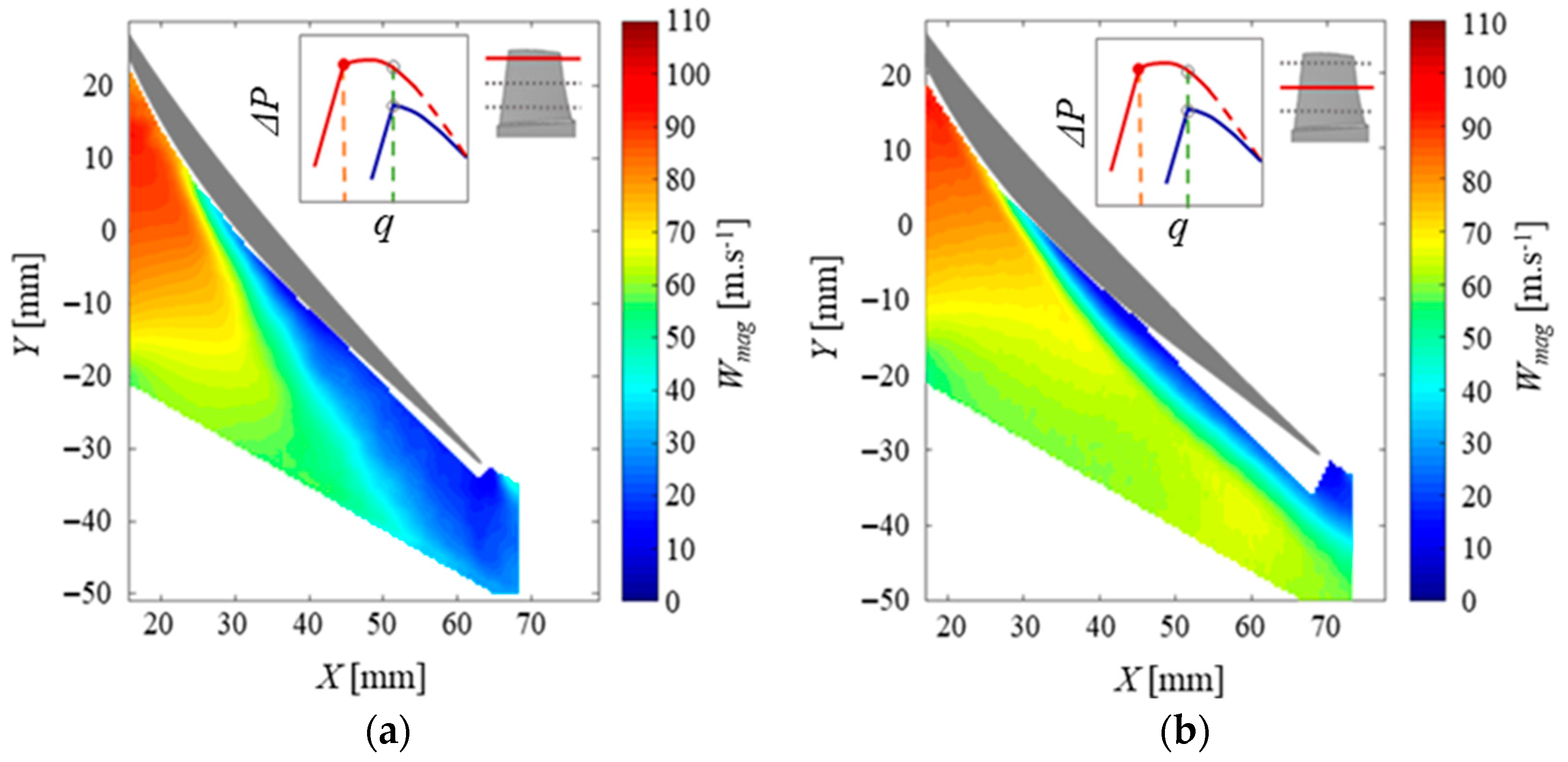

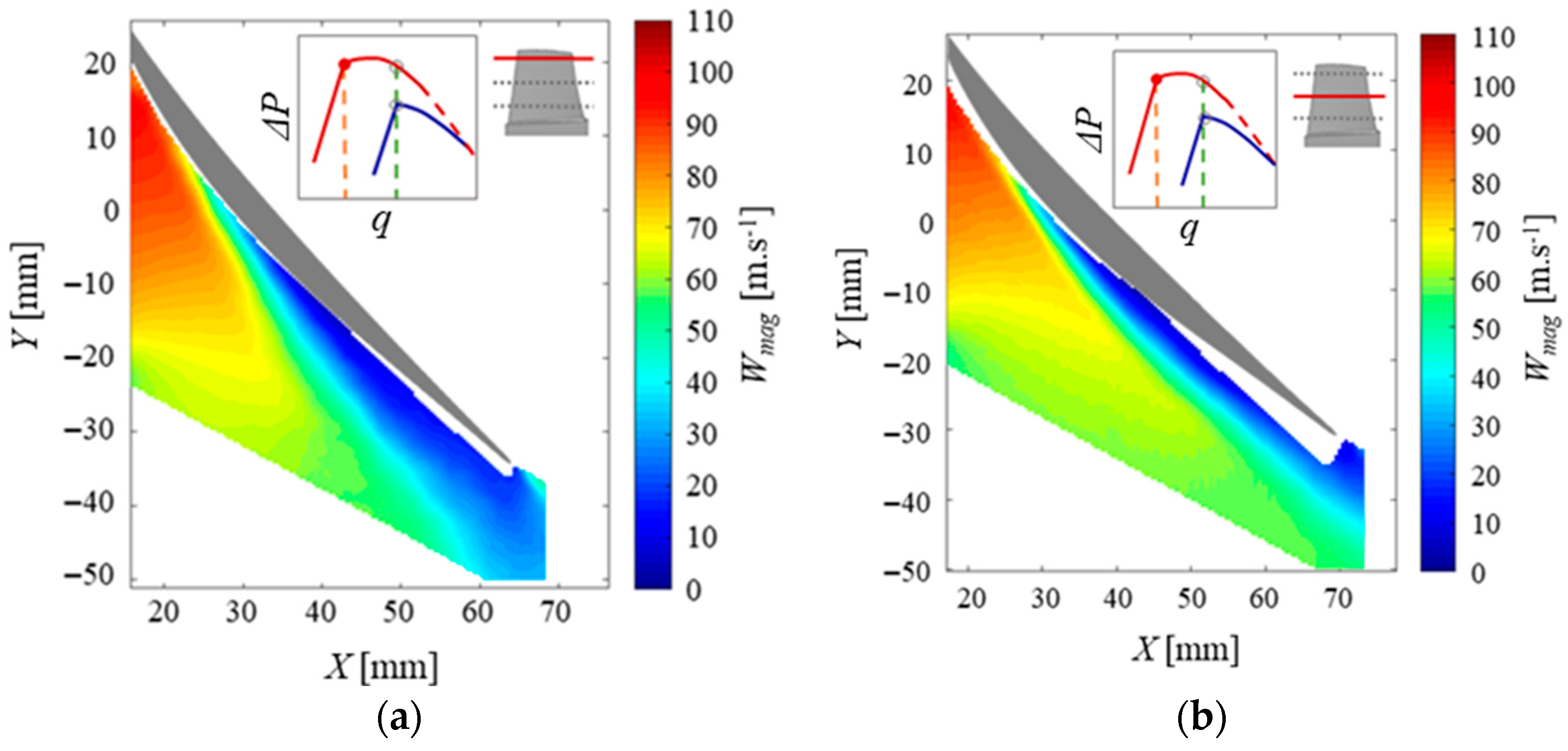

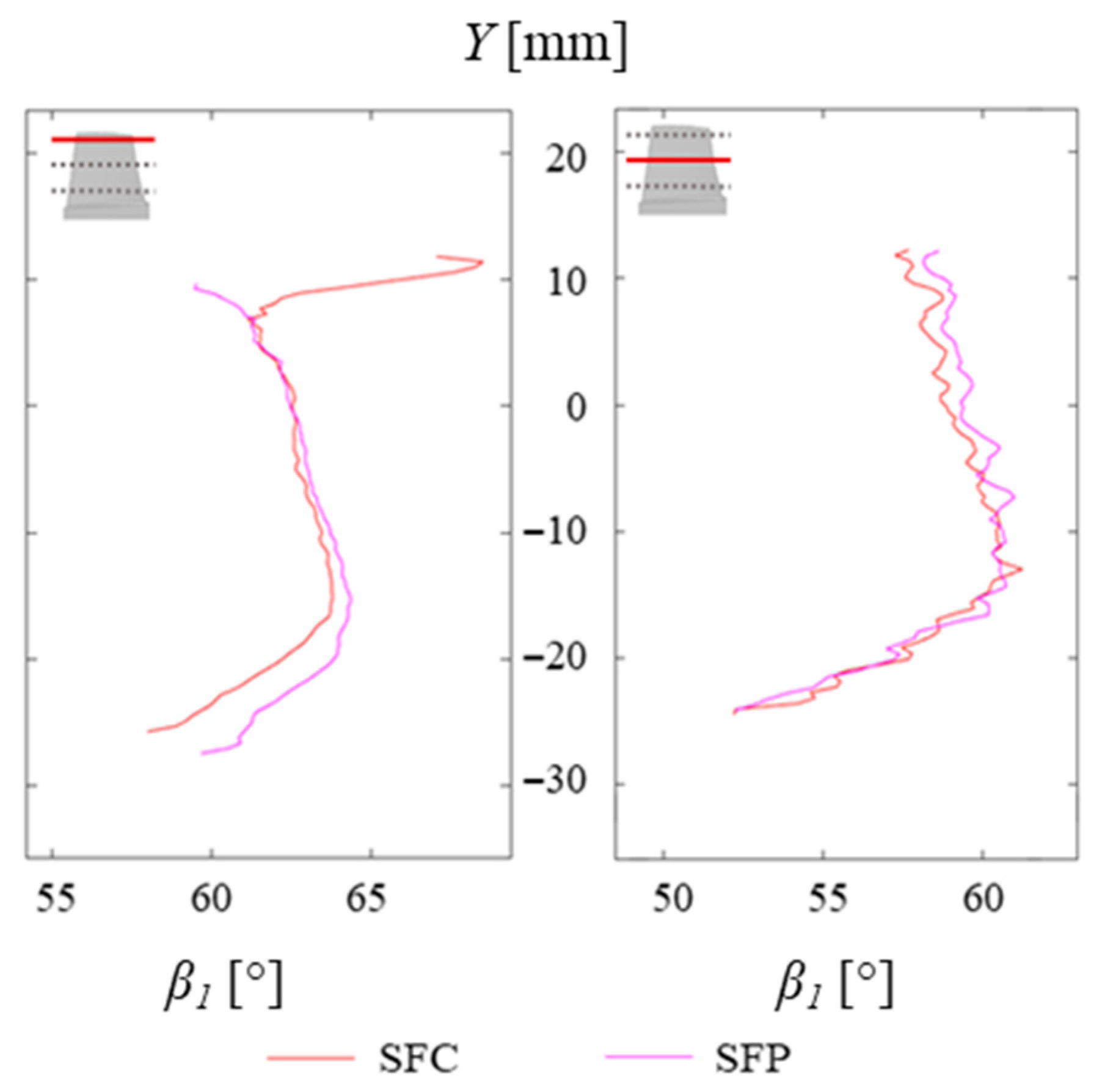

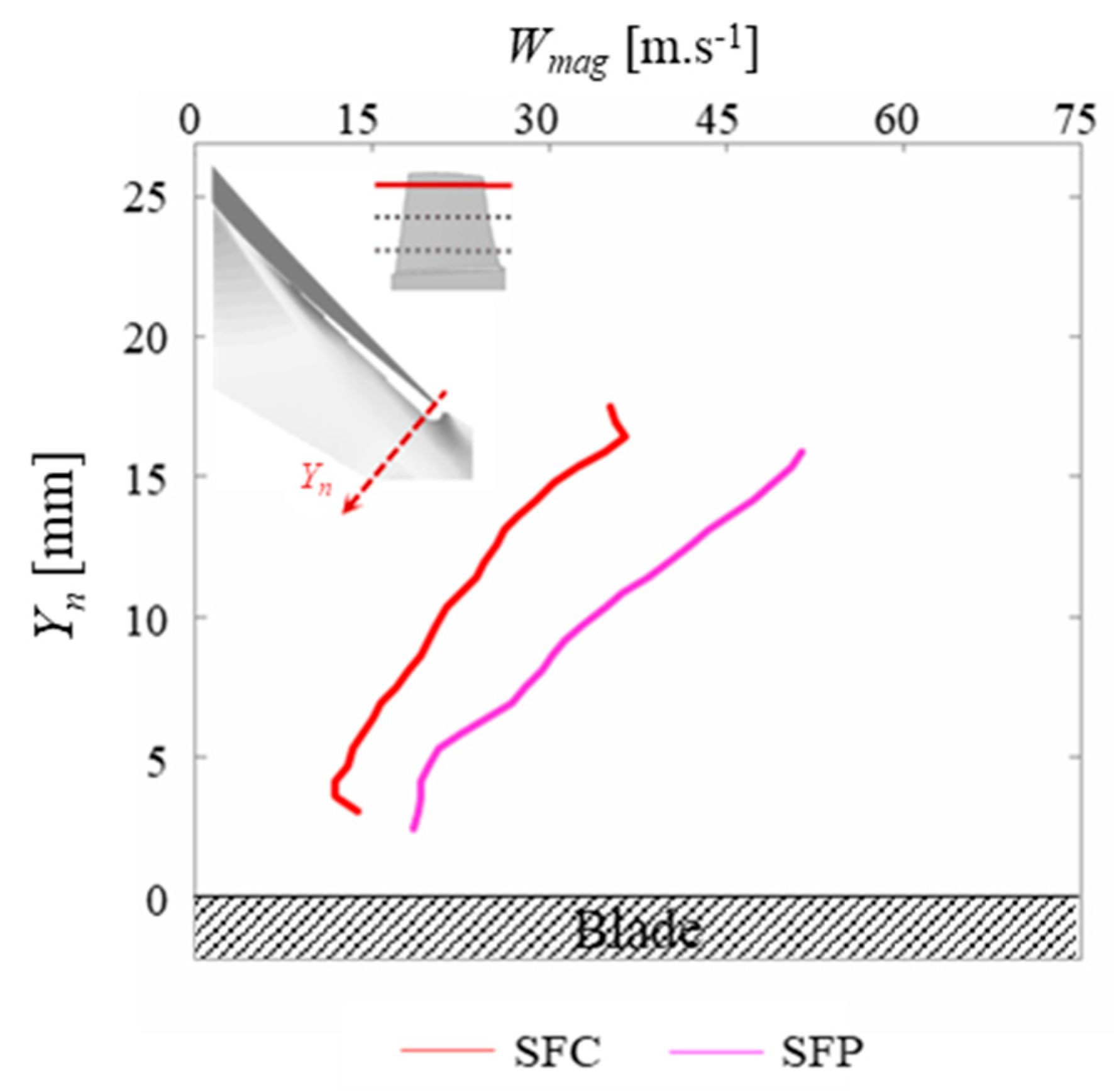

- A controlled configuration with continuous blowing at a reduced injected mass flow (Qinj = 0.82% of the stall mass flow) compared to the results previously presented in [21] (Qinj = 2.5%). It corresponds to point A in Figure 5 and is labelled SFC in the following. Please note that this configuration involves switching off five pairs of actuators, compared with [21]. Deactivated pairs of actuators are evenly distributed around the casing (one pair every four pairs);

- A controlled configuration with nearly the same reduced injected mass flow (Qinj = 0.83%) but operated in pulsed blowing. It corresponds with point B in Figure 5 and is labelled SFP in the following. Please note that frequency (f = 424 Hz) and duty cycle (DC = 0.7) were chosen accordingly to obtain this particular mass flow.

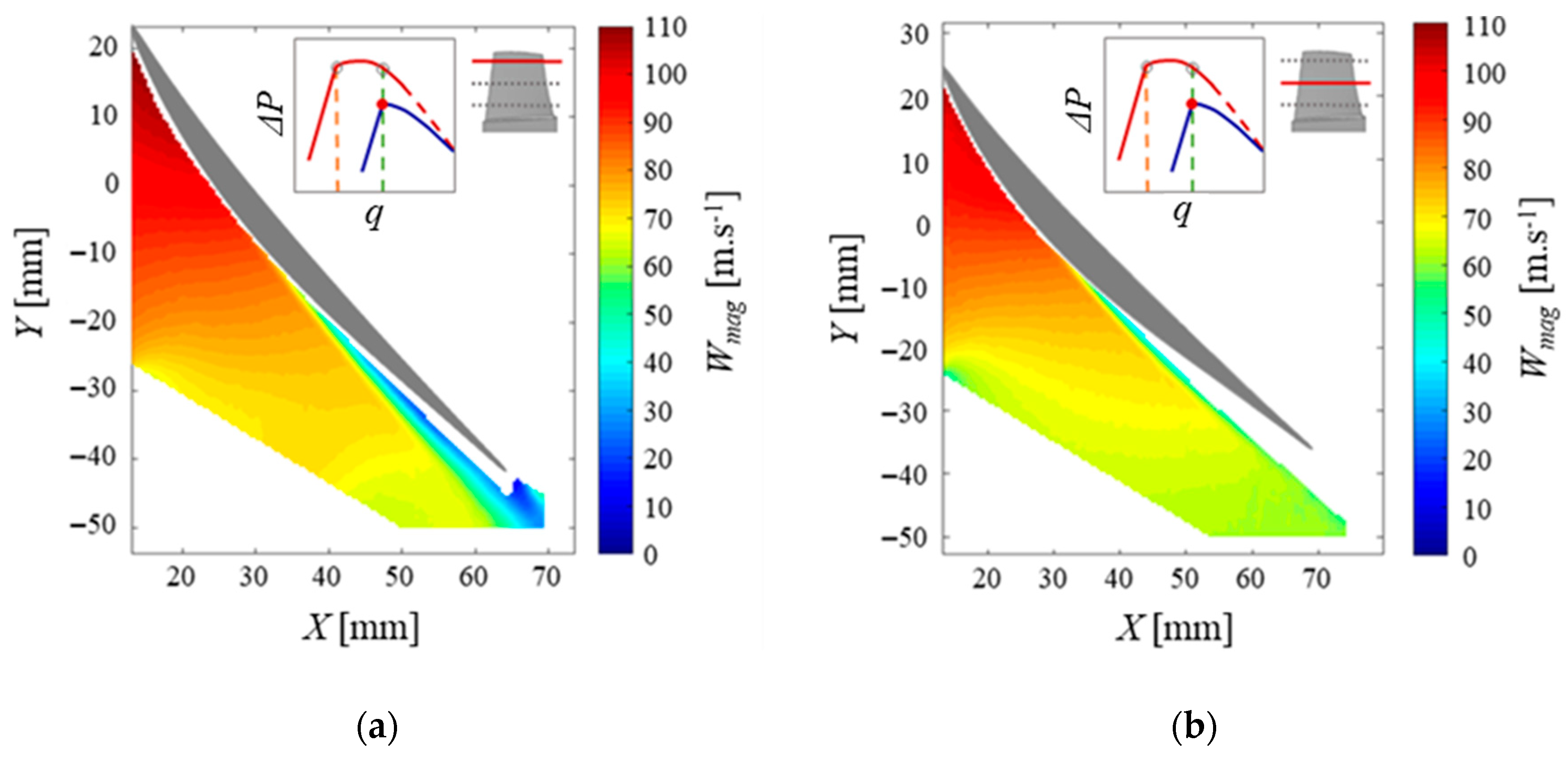

3.1. Last “Natural” Stable Point with and Without Control

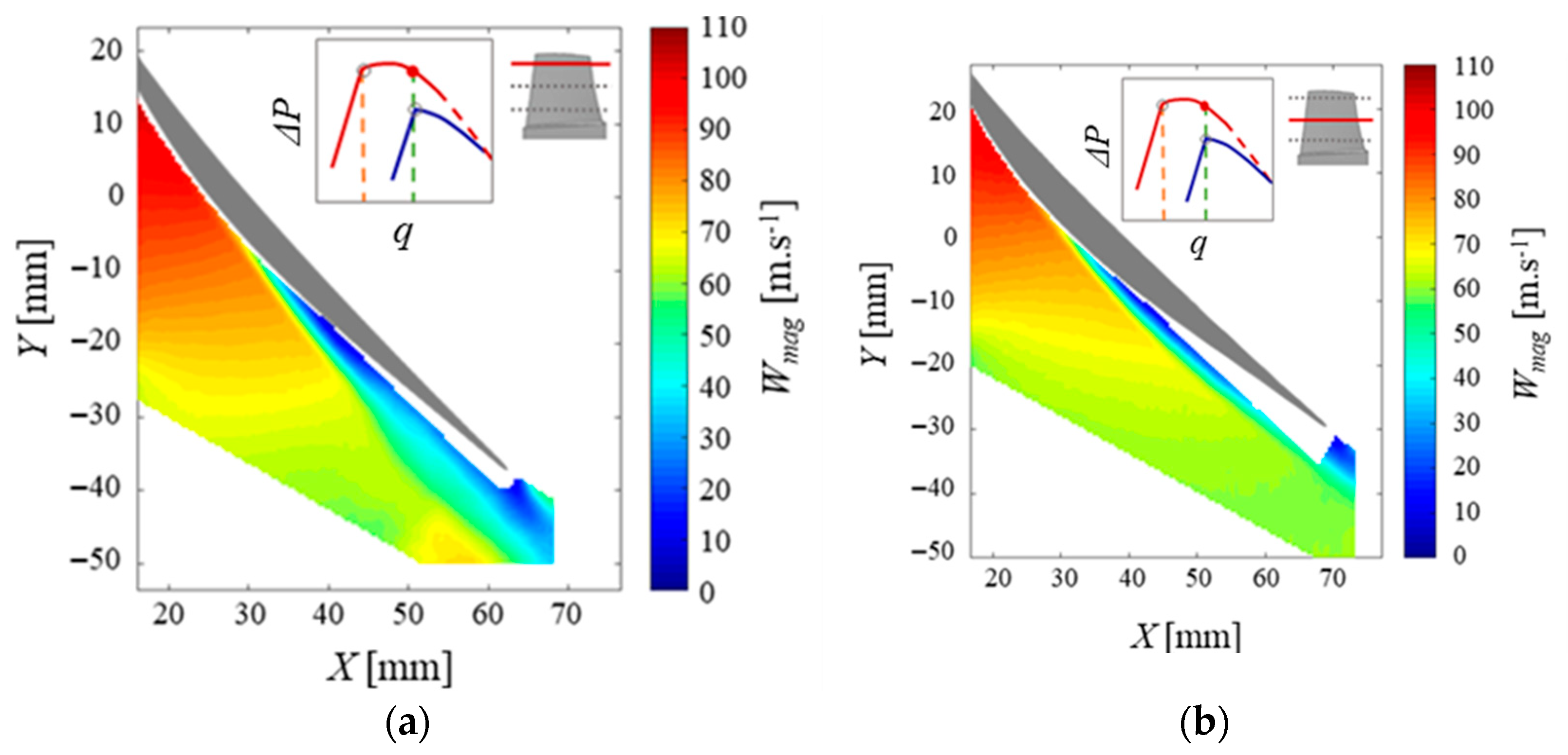

3.2. Last Stable Point with Control

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Day, I.J. Stall, Surge, and 75 Years of Research. J. Turbomach. 2016, 138, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhi, S. Aircraft Propulsion: Cleaner, Leaner, and Greener, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-119-71864-2. [Google Scholar]

- Camp, T.R.; Day, I.J. A Study of Spike and Modal Stall Phenomena in a Low-Speed Axial Compressor. In Volume 1: Aircraft Engine; Marine; Turbomachinery; Microturbines and Small Turbomachinery; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Orlando, FL, USA, 1997; p. V001T03A109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, I.J. Stall Inception in Axial Flow Compressors. J. Turbomach. 1993, 115, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullan, G.; Young, A.M.; Day, I.J.; Greitzer, E.M.; Spakovszky, Z.S. Origins and Structure of Spike-Type Rotating Stall. J. Turbomach. 2015, 137, 051007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewkin-Smith, M.; Pullan, G.; Grimshaw, S.D.; Greitzer, E.M.; Spakovszky, Z.S. The Role of Tip Leakage Flow in Spike-Type Rotating Stall Inception. J. Turbomach. 2019, 141, 061010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, W.T. History, Philosophy, Physics, and Future Directions of Aircraft Propulsion System/Inlet Integration. In Volume 2: Turbo Expo 2004; ASMEDC: Vienna, Austria, 2004; pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spakovszky, Z.S.; Weigl, H.J.; Paduano, J.D.; Van Schalkwyk, C.M.; Suder, K.L.; Bright, M.M. Rotating Stall Control in a High-Speed Stage with Inlet Distortion: Part I—Radial Distortion. J. Turbomach. 1999, 121, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spakovszky, Z.S.; Van Schalkwyk, C.M.; Weigl, H.J.; Paduano, J.D.; Suder, K.L.; Bright, M.M. Rotating Stall Control in a High-Speed Stage with Inlet Distortion: Part II—Circumferential Distortion. J. Turbomach. 1999, 121, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermüller, M.; Schmidt, K.; Schulte, H.; Peitsch, D. Some Aspects on Wet Compression—Physical Effects and Modeling Strategies Used in Engine Performance Tools. In LTH—Luftfahrttechnisches Handbuch/Aeronautical Engineering Handbook; LTH-Koordinierungsstelle at IABG mbH: Ottobrunn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Yu, C.; Lin, F.; Nie, C. Measurements and Visualization of Process From Steady State to Stall in an Axial Compressor with Water Ingestion. In Volume 6C: Turbomachinery; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2013; p. V06CT42A032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, H.; Lin, A. Effects of Water In-gestion on the Tip Clearance Flow in Compressor Rotors. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 233, 4235–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, N.; Kurosaki, M.; Ohta, Y.; Outa, E.; Nakajima, T.; Nakakita, T. Early Stall Warning Technique for Axial-Flow Compressors. J. Turbomach. 2007, 129, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, M.D. Passive Endwall Treatments for Enhancing Stability; NASA: Houston, TX, USA, 2007; NASA/TM-2007-214409.

- Cumpsty, N.A. Part-Circumference Casing Treatment and the Effect on Compressor Stall. In Volume 1: Turbomachinery; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1989; p. V001T01A110. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.D.J.; Cumpsty, N.A. Flow Phenomena in Compressor Casing Treatment. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1984, 106, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassina, G.; Beheshti, B.H.; Kammerer, A.; Abhari, R.S. Parametric Study of Tip Injection in an Axial Flow Compressor Stage. In Volume 6: Turbo Expo 2007, Parts A and B; AS-MEDC: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2007; pp. 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Du, J.; Nie, C.; Zhang, H. Review of Tip Air Injection to Improve Stall Margin in Axial Compressors. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2019, 106, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalida, G.; Joseph, P.; Roussette, O.; Dazin, A. Active Flow Control in an Axial Compressor for Stability Improvement: On the Effect of Flow Control on Stall Inception. Exp. Fluids 2021, 62, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stößel, M.; Bindl, S.; Niehuis, R. Ejector Tip Injection for Active Compressor Stabilization. In Volume 2A: Turbomachinery; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2014; p. V02AT37A004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubogha Moubogha, J.; Joseph, P.; Roussette, O.; Dazin, A. Experimental Flow Investigation Inside an Axial Compressor with Active Flow Control. In Volume 10A: Turbomachinery—Axial Flow Fan and Compressor Aerodynamics; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; p. V10AT29A022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, R.; Behnken, R.L.; Murray, R.M. Rotating Stall Control of an Axial Flow Compressor Using Pulsed Air Injection. J. Turbomach. 1997, 119, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefalakis, M.; Papailiou, K.D. Active Flow Control for Increasing the Surge Margin of an Axial Flow Compressor. In Volume 6: Turbomachinery, Parts A and B; ASMEDC: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; pp. 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubogha Moubogha, J.; Margalida, G.; Joseph, P.; Roussette, O.; Dazin, A. Stall Margin Improvement in an Axial Compressor by Continuous and Pulsed Tip Injection. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2022, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseik, O.; Joseph, P.; Roussette, O.; Dazin, A. Experimental investigation by Particle Image Velocimetry of the active flow control of the stall inception of an axial compressor. In Proceedings of the 16th European Turbomachinery Conference, paper n. ETC2025-143, Hannover, Germany, 24–28 March 2025; Available online: https://www.euroturbo.eu/publications/conference-proceedings-repository/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Baretter, A.; Joseph, P.; Roussette, O.; Dazin, A.; Romanò, F. Scaling Laws at Stall in an Axial Compressor with an Upstream Perturbation. J. Propuls. Power 2025, 41, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wygnanski, I. On the Need to Reassess the Design Tools for Active Flow Control. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2024, 146, 100995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the EUROTURBO. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alekseik, O.; Joseph, P.; Roussette, O.; Dazin, A. An Experimental Investigation by Particle Image Velocimetry of the Active Flow Control of the Stall Inception of an Axial Compressor. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2025, 10, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp10040040

Alekseik O, Joseph P, Roussette O, Dazin A. An Experimental Investigation by Particle Image Velocimetry of the Active Flow Control of the Stall Inception of an Axial Compressor. International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power. 2025; 10(4):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp10040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlekseik, Olha, Pierric Joseph, Olivier Roussette, and Antoine Dazin. 2025. "An Experimental Investigation by Particle Image Velocimetry of the Active Flow Control of the Stall Inception of an Axial Compressor" International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power 10, no. 4: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp10040040

APA StyleAlekseik, O., Joseph, P., Roussette, O., & Dazin, A. (2025). An Experimental Investigation by Particle Image Velocimetry of the Active Flow Control of the Stall Inception of an Axial Compressor. International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power, 10(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp10040040