Factors Associated with Complications of Snakebite Envenomation in Health Facilities in the Cascades Region of Burkina Faso from 2016 to 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Measurement of Variables

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.1.2. Clinical Characteristics

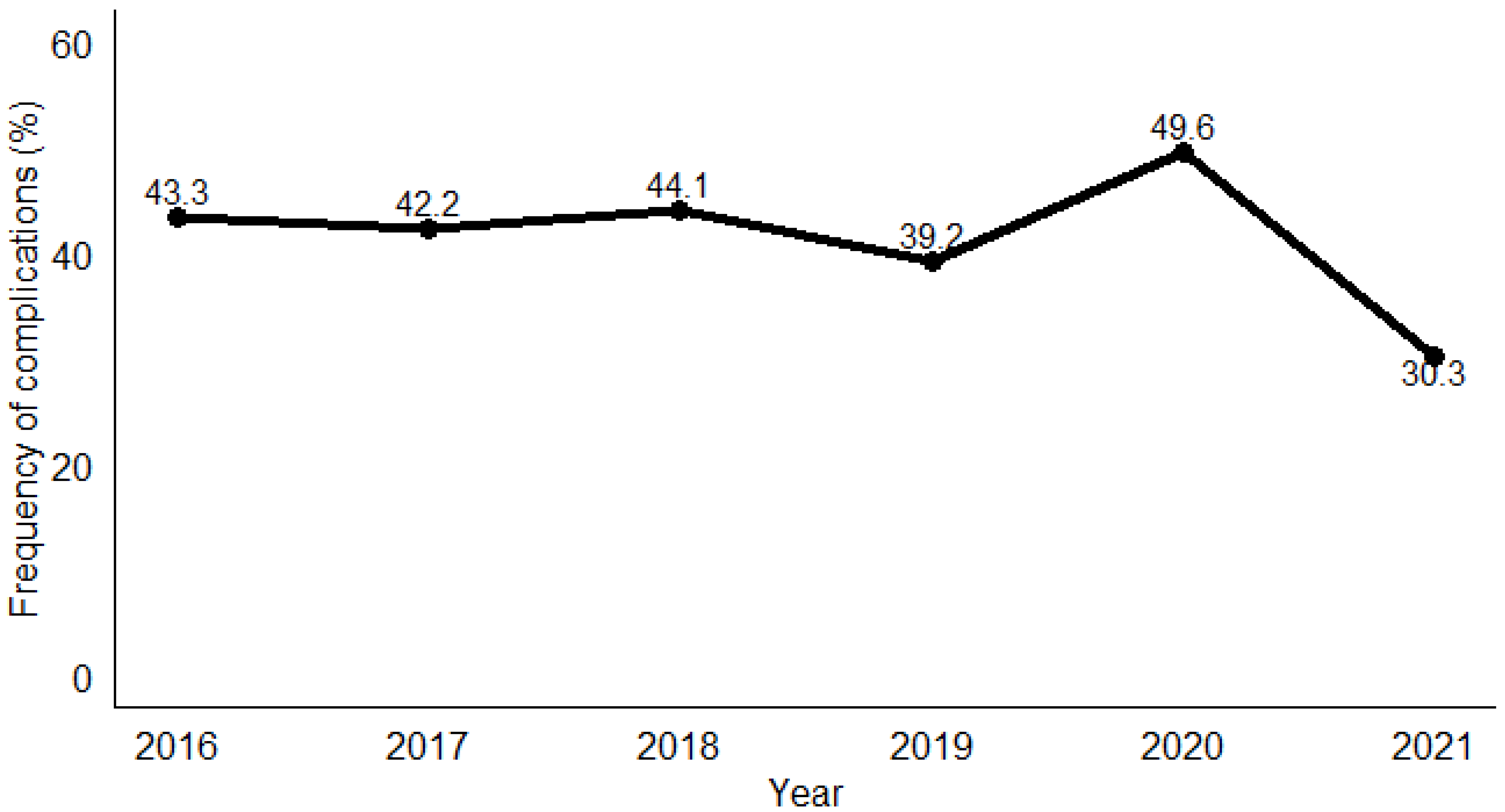

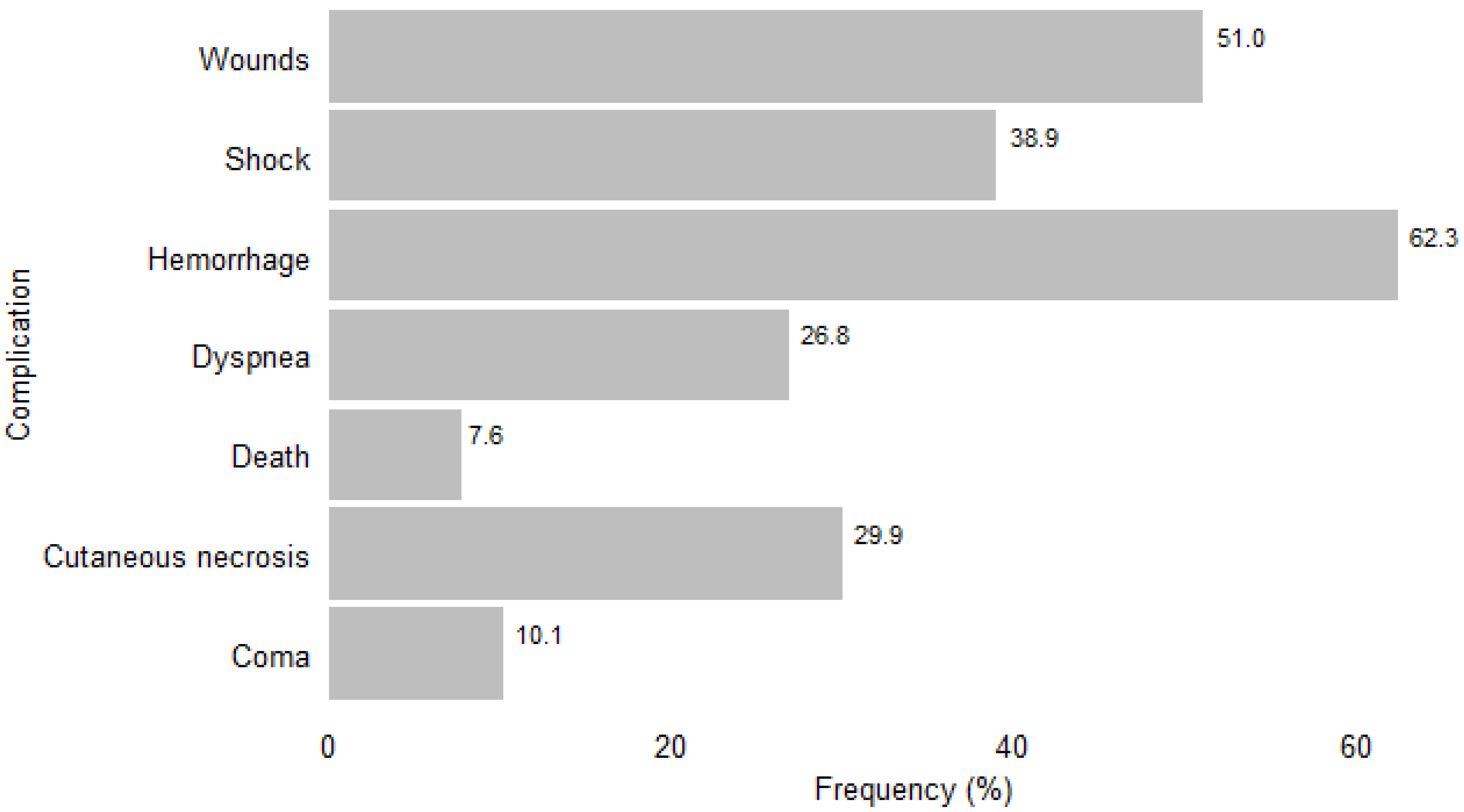

3.2. Frequency of Complications of Snakebite Envenomation

3.3. Factors Associated with Snakebite Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Massougbodji, A.; Habib, A.G. The WHO strategy for prevention and control of snakebite envenoming: A sub-Saharan Africa plan. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 25, e20190083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Akaffou, M.H.; Allali, B.K.; Dosso, M.; Massougbodji, A.; Barraviera, B. The 6th international conference on envenomation by Snakebites and Scorpion Stings in Africa: A crucial step for the management of envenomation. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Snakebite Envenoming: A Strategy for Prevention and Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515641 (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Alcoba, G.; Chabloz, M.; Eyong, J.; Wanda, F.; Ochoa, C.; Comte, E.; Nkwescheu, A.; Chappuis, F. Snakebite epidemiology and health-seeking behavior in Akonolinga health district, Cameroon: Cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touré, M.; Coulibaly, M.; Koné, J.; Diarra, M.; Coulibaly, B.; Beye, S.; Diallo, B.; Dicko, H.; Nientao, O.; Doumbia, D.; et al. Complications aigues de l’envenimation par morsures de serpent au service de réanimation du CHU mère enfant “LE Luxembourg” de Bamako. Mali. Méd. 2019, 34, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chippaux, J.-P. Estimate of the burden of snakebites in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-analytic approach. Toxicon 2011, 57, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampini, S.; Nassouri, S.; Chippaux, J.-P.; Semde, R. Retrospective study on the incidence of envenomation and accessibility to antivenom in Burkina Faso. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamogo, R.; Nikièma, A.S.; Belem, M.; Thiam, M.; Diatta, Y.; Dabiré, R.K. Cross-sectional ethnobotanical survey of plants used by traditional health practitioners for snakebite case management in two regions of Burkina Faso. Phytomed. Plus 2023, 3, 100471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, F.; Chippaux, J.P. Prise en charge des morsures de serpent en Afrique. Lett. L’infect. 2016, Tome XXXI, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Bamogo, R.; Thiam, M.; Nikièma, A.S.; Somé, F.A.; Mané, Y.; Sawadogo, S.P.; Sow, B.; Diabaté, A.; Diatta, Y.; Dabiré, R.K. Snakebite frequencies and envenomation case management in primary health centers of the Bobo-Dioulasso health district (Burkina Faso) from 2014 to 2018. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 115, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Koudou, G.B.; Bagot, M.; Drabo, F.; Bougma, W.R.; Pulford, C.; Bockarie, M.; Harrison, R.A. Health and economic burden estimates of snakebite management upon health facilities in three regions of southern Burkina Faso. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouédraogo, P.V.; Traoré, C.; Savadogo, A.A.; Bagbila, W.P.A.H.; Galboni, A.; Ouédraogo, A.; Sere, I.S.; Millogo, A. Hémorragie cérébro-méningée secondaire à une envenimation par morsure de serpent: À propos de deux cas au Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sourô Sanou de Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Med. Trop. Sante Int. 2022, 2, MTSI.2022.131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabilgou, A.A.; Sondo, A.; Dravé, A.; Diallo, I.; Kyelem, J.M.A.; Napon, C.; Kaboré, J. Hemorrhagic stroke following snake bite in Burkina Faso (West Africa). A case series. Trop. Dis. Travel. Med. Vaccines 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyelem, C.; Yaméogo, T.; Ouédraogo, S.; Zoungrana, J.; Poda, G.; Rouamba, M.; Ouangré, A.; Kissou, S.; Rouamba, A. Snakebite in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso: Illustration of realities and challenges for care based on a clinical case. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 18, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P. Les serpents d’Afrique occidentale et centrale. Éditions de l’IRD (EX-ORSTOM). 2001;310. Available online: https://www.editions.ird.fr/produit/232/9782709920001/les-serpents-d-afrique-occidentale-et-centrale (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Chirio, L. Inventaire des reptiles de la région de la Réserve de Biosphère Transfrontalière du W (Niger/Bénin/Burkina Faso: Afrique de l’Ouest). Bull. Soc. Herp. Fr. 2009, 132, 13–41. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics and Demography. Fifth General Census of Population and Housing in Burkina Faso. 2022. Available online: https://burkinafaso.opendataforafrica.org (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Chippaux, J.-P. Management of Snakebites in Sub-Saharan Africa. Méd. Santé Trop. 2015, 25, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M.F.; Vianney, J.-M., Sr.; Heitz-Tokpa, K.; Kreppel, K. Risks of snakebite and challenges to seeking and providing treatment for agro-pastoral communities in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglanu, L.M.; Amuasi, J.H.; Schut, B.A.; Steinhorst, J.; Beyuo, A.; Dari, C.D.; Agbogbatey, M.K.; Blankson, E.S.; Punguyire, D.; Lalloo, D.G.; et al. What the snake leaves in its wake: Functional limitations and disabilities among snakebite victims in Ghanaian communities. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhaskar, D.; Agarwal, A.; Bhalla, G. A study of clinical profile of snake bite at a tertiary care centre. Toxicol. Int. 2014, 21, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steinhorst, J.; Aglanu, L.M.; Ravensbergen, S.J.; Dari, C.D.; Abass, K.M.; Mireku, S.O.; Adu Poku, J.K.; Enuameh, Y.A.K.; Blessmann, J.; Harrison, R.A.; et al. ‘The medicine is not for sale’: Practices of traditional healers in snakebite envenoming in Ghana. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndu, I.; Edelu, B.; Ekwochi, U. Snakebites in a Nigerian children Population: A 5-year review. Sahel. Med. J. 2018, 21, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nann, S. How beliefs in traditional healers impact on the use of allopathic medicine: In the case of indigenous snakebite in Eswatini. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerardo, C.J.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Evans, C.S.; Simel, D.L.; Lavonas, E.J. Does This Patient Have a Severe Snake Envenomation?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essafti, M.; Fajri, M.; Rahmani, C.; Abdelaziz, S.; Mouaffak, Y.; Younous, S. Snakebite envenomation in children: An ongoing burden in Morocco. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 77, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagener, M.; Naidoo, M.; Aldous, C. Wound infection secondary to snakebite. S. Afr. Med. J. 2017, 107, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajeeth Kumar, K.; Narayanan, S.; Udayabhaskaran, V.; Thulaseedharan, N. Clinical and epidemiologic profile and predictors of outcome of poisonous snake bites – an analysis of 1500 cases from a tertiary care center in Malabar, North Kerala, India. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2018, 11, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, M.; Mangane, M.I.; Ouedrago, Y.; Koita, S.A.; Madane, D.T.; Hamidou, A.A.; Nientao, O.; Bagayogo, D.K.; Dembele, A.S.; Djibo, D.M.; et al. Overview of poisoning by snake bite in 2019 at UHC Gabriel Touré of Bamako: Clinical features, prognosis and evaluation of the availability of antivenom serum. Méd. Intensive Réanim. 2021, 7, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Harikrishnan, M.P.; Anil Kumar, C.R.; Anand, M.K.; Earali, J. Effects of hemotoxic snake bite envenomation on haematological parameters variability in predicting complications. Int. J. Med. Med. Res. 2021, 6, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Masroori, S.; Al Balushi, F.; Al Abri, S. Evaluation of Risk Factors of Snake Envenomation and Associated Complications Presenting to Two Emergency Departments in Oman. Oman Med. J. 2022, 37, e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number (n = 846) | Values (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) a | 17 (10–32) | |

| Age range a | ||

| ≥30 | 251 | 29.7 |

| 15–29 | 226 | 26.7 |

| <15 | 369 | 43.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 462 | 54.6 |

| Female | 384 | 45.4 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 100 | 11.8 |

| Rural | 746 | 88.2 |

| Period of the year | ||

| First half b | 416 | 49.2 |

| Second half b | 430 | 50.8 |

| Characteristics | Number (n = 846) | Values (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | ||

| Yes | 50 | 5.9 |

| No | 796 | 94.1 |

| Local incision | ||

| Yes | 201 | 23.8 |

| No | 645 | 76.2 |

| Tourniquet | ||

| Yes | 67 | 7.9 |

| No | 779 | 92.1 |

| Black stone | ||

| Yes | 118 | 13.9 |

| No | 728 | 86.1 |

| Local signs | ||

| Yes | 811 | 95.9 |

| No | 35 | 4.1 |

| Abnormal vital signs | ||

| Yes | 413 | 48.8 |

| No | 433 | 51.2 |

| Bleeding/Hemorrhage | ||

| Yes | 275 | 32,5 |

| No | 571 | 67.5 |

| Dyspnea | ||

| Yes | 95 | 11.2 |

| No | 751 | 88.8 |

| Neurological signs | ||

| Yes | 53 | 6.3 |

| No | 793 | 93.7 |

| Ophthalmological signs | ||

| Yes | 17 | 2.0 |

| No | 829 | 98.0 |

| Serum antivenom | ||

| Yes | 590 | 69.7 |

| No | 256 | 30.3 |

| Features | OR a | 95% CI | p-Value | AOR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Low | High | |||||

| Gender | 0.3 | |||||||

| Female | 1 | |||||||

| Male | 1.17 | 0.89 | 1.54 | |||||

| Age (years) | 0.01 | 0.047 | ||||||

| ≥30 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 15–29 | 1.41 | 0.95 | 2.13 | 1.87 | 1.03 | 3.44 | ||

| <15 | 1.78 | 1.2 | 2.66 | 2.04 | 1.14 | 3.72 | ||

| Place of residence | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Urban | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Rural | 6.92 | 3.8 | 13.9 | 4.8 | 2.21 | 11.4 | ||

| Time of year | 0.4 | |||||||

| First half b | 1 | |||||||

| Second half b | 0.9 | 0.68 | 1.18 | |||||

| Comorbidity | 0.003 | |||||||

| No | 1 | |||||||

| Yes | 2.38 | 1.33 | 4.35 | |||||

| Local incision | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 7.77 | 5.4 | 11.4 | 4.31 | 2.51 | 7.52 | ||

| Tourniquet | <0.001 | 0.011 | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 35.8 | 13.1 | 147 | 5.52 | 1.42 | 30.8 | ||

| Black stone | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.46 | 1.66 | 3.69 | |||||

| Local signs | 0.8 | |||||||

| No | 1 | |||||||

| Yes | 1.09 | 0.55 | 2.22 | |||||

| Abnormal vital signs | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 16 | 11.4 | 22.9 | 14.3 | 9.22 | 22.7 | ||

| Bleeding | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 14.3 | 10 | 20.6 | 14.2 | 8.8 | 23.4 | ||

| Neurological signs | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 1 | |||||||

| Yes | 19.5 | 7.86 | 65 | |||||

| Serum antivenom | 0.2 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| No | 0.8 | 0.59 | 1.08 | 2.92 | 1.8 | 4.8 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kinda, R.; Sidibe, S.; Zongo, D.; Millogo, T.; Delamou, A.; Kouanda, S. Factors Associated with Complications of Snakebite Envenomation in Health Facilities in the Cascades Region of Burkina Faso from 2016 to 2021. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9110268

Kinda R, Sidibe S, Zongo D, Millogo T, Delamou A, Kouanda S. Factors Associated with Complications of Snakebite Envenomation in Health Facilities in the Cascades Region of Burkina Faso from 2016 to 2021. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2024; 9(11):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9110268

Chicago/Turabian StyleKinda, Rene, Sidikiba Sidibe, Dramane Zongo, Tieba Millogo, Alexandre Delamou, and Seni Kouanda. 2024. "Factors Associated with Complications of Snakebite Envenomation in Health Facilities in the Cascades Region of Burkina Faso from 2016 to 2021" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 9, no. 11: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9110268

APA StyleKinda, R., Sidibe, S., Zongo, D., Millogo, T., Delamou, A., & Kouanda, S. (2024). Factors Associated with Complications of Snakebite Envenomation in Health Facilities in the Cascades Region of Burkina Faso from 2016 to 2021. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 9(11), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9110268