The Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis Patients at Adare General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia (A Five-Year Retrospective Study)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

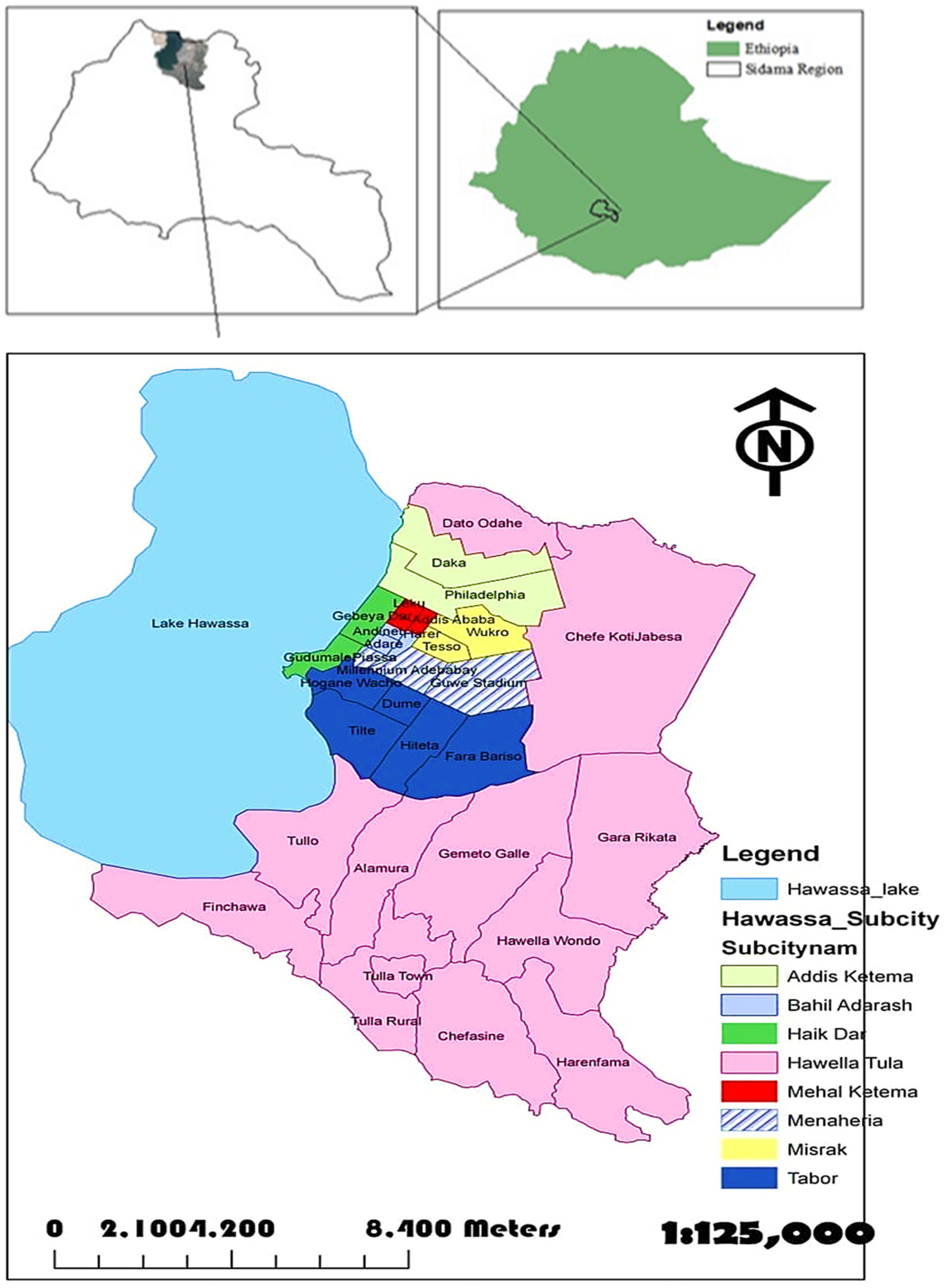

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Study Design, Period and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Operational Definition

3. Result

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients

3.2. Treatment Outcome of the Participants

3.3. Treatment Outcomes of TB and Their Trends

3.4. Treatment Success Rate and Its Associated Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Strength of the study

- Limitations

- Biases

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| DOTS | Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course |

| EPTB | Extra-pulmonary TB |

| FMOH | Federal Ministry of Health |

| MTB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| NTLCP | National TB and Leprosy Control Program |

| SNNPR | Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples‘ Region |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Science |

| PTB | Pulmonary tuberculosis |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Patrick, O.E.; Winifred, A.O. Success of the Control of Tuberculosis in Nigeria: A Review. Int. J. Health Res. 2009, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, L.C. The Molecular Basis of Resistance in Mycobaterium tuberculosis. Open J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 12, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Tuberculosiskey Facts; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FMOH. TB/HIV Implementation Guideline; FMOH: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- FMOH. Tuberculosis, Leprosy and TB/HIV Prevention and Control Program Manual, 4th ed.; FMOH: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- FMOH; TB Research Advisory Committee (TRAC). Road Map for Tuberculosis Operational Research in Ethiopia; FMOH: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- FMOH. Health Sector Development Programme IV; FMOH: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Belete, G.; Gobena, A.; Girmay, M.; Sibhatu, B. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Belay, T.; Abebe, M.; Assegedech, B.; Dieter, R.; Frank, E.; Ulrich, S. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at Gondar University Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: A five-year retrospective study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 1471–2458. [Google Scholar]

- Yassin, M.A.; Datiko, D.G.; Shargie, E.B. Ten-year experiences of the tuberculosis control programme in the southern region of Ethiopia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2006, 10, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Tsegahun, A.; Moges, L.; Helen, T. Trends and Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis in DebreBerhan Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. Clin. Med. Res. 2018, 7, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- FMOH. An Extract of Five Year’s TB, TB/HIV AND Leprosy Control Program Analysis; FMOH: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Biruk, M.; Yimam, B.; Abrha, H.; Biruk, S.; Amdie, F.Z. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis and associated factors in an Ethiopian University Hospital. Adv. Public Health 2016, 2016, 8504629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrezgabiher, G.; Romha, G.; Ejeta, E.; Asebe, G.; Zemene, E.; Ameni, G. Treatment Outcome of Tuberculosis Patients under Directly Observed Treatment Short Course and Factors Affecting Outcome in Southern Ethiopia: A Five-YearRetrospectivestudy. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girum, T.; Atkure, D.; Tefera, T.; Abebe, B.; Theodros, G.; Habtamu, T.; Geremew, G.; Misrak, G.; Mengistu, T.; Minilik, D. Treatment Outcome and Associated Factors among TB Patients in Ethiopia: Hospital-Based Retrospective Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 6, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Getahun, A.; Haimanot, D.; Takele, T.; Gebremedihin, G.; Ketema, T.; Gobena, A. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at Gambella Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia: Three-year Retrospective study. J. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2015, 3, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, D.; Derbie, A.; Mekonnen, H.; Zenebe, Y. Profile and Treatment outcomes of patients with tuberculosis in Northeastern Ethiopia: Across Sectional study. Afr. Health Sci. 2016, 16, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FMOH. Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Health Guidelines for Clinical and Programmatic Management of TB and Leprosy and TB/HIV in Ethiopia, 5th ed.; FMOH: Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gebretsadik, B.; Fikre, E.; Abreham, A. Treatment outcome of smear-Positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1471–2458. [Google Scholar]

- Endris, M.; Moges, F.; Belyhun, Y.; Woldehana, E.; Esmael, A.; Unakal, C. Treatment Outcome of tuberculosis patients at Enfraz health Center, northwest ethiopia: A five-year retrospective study. Tuberc. Res. Treat 2014, 2014, 726193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisay, S.; Mengistu, B.; Erku, W.; Woldeyohannes, D. Directly Observed Treatment Short-course (DOTS) for tuberculosis control program in Gambella Regional State, Ethiopia: Ten years experience. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejeta, E.; Chla, M.; Arega, G.; Ayalsew, K.; Tesfaye, L.; Birhanu, T.; Disassa, H. Treatment outcome of Tuberculosis patients Under Directly Observed Treatment of Short Course in Nekemt Town, Western Ethiopia: Retrospective Cohort Study. Gen. Med. 2015, 3, 1000176. [Google Scholar]

- Tigist, M.; Kidist, D.; Degefa, H.; Taye, L. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients in Nigist Eleni Mohammed General Hospital, Hosanna, South Ethiopia, a five year retrospective study. Arch. Public Health 2016, 16, 201775. [Google Scholar]

- Ramya, A.; Kaliyaperumal, K.; Marimuthu, G. The profile and treatment outcomes of the older (aged 60 years and above) tuberculosis patients in Tamilnadu, South India. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67288. [Google Scholar]

- Duru, C.B.; Uwakwe, K.A.; Nnebue, C.C.; Diwe, K.C.; Merenu, I.A.; Emerole, C.O.; Iwu, C.A.; Duru, C.A. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and determinants among patients treated in hospitals in Imo state, Nigeria. Open Access Libr. J. 2016, 3, e2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabida, M.; Tshimanga, M.; Chemhuru, M.; Gombe, N.; Bangure, D. Trends for tuberculosis treatment outcomes, New sputum smear positive patients in kwekwe district, Zimbabwe, 2007–2011: A cohort analysis. J. Tuberc. Res. 2015, 3, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aysun, S.; Aka, A.; Yusuf, A.; Nurullah, K.; Nagihan, K.; Fatma, T. Factors affecting successful treatment outcomes in pulmonary tuberculosis: A single-center experience in Turkey, 2005–2011. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 9, 821–828. [Google Scholar]

- Mariade, F.; Pessoa, M.; Albuquerque, R.; Arraes de, A.; Ximenes, N.; Lucena-Silva, W. Factors associated with treatment failure, Dropout and death in a cohort of tuberculosis patients (from May 2001 to July 2003) in Recife, Pernambuco State, Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2007, 23, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar]

- Firdie, T.; Tariku, D.; Tsegaye, T. Treatment outcomes of TB patients at Debre Berhan Hospital, Amahara Region, North Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2016, 26, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gadoev, J.; Asadov, D.; Tillashaykhov, M.; Tayler-Smith, K.; Isaakidis, P.; Dadu, A.; de Colombani, P.; Hinderaker, S.G.; Parpieva, N.; Jalolov, A.; et al. Factors associated with unfavorable treatment outcomes in new and previously treated TB patients in Uzbekistan: A five year countrywide study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nik, N.; Ronaidi, N.M.; Mohd, N.S.; WanMohammad, Z.; Sharina, D.; Nik, R.N.H. Factors associated with unsuccessful treatment outcome of pulmonary tuberculosis in Kotabharu, Kelantan: A retrospective cohort study. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2011, 11, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Addisu, M.; Balew, Z.; Biniam, E. Treatment outcome and Associated Factors among Tuberculosis Patients in Debre Tabor, North Ethiopia: A Retrospective Study. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 1354356. [Google Scholar]

- Ketema, T.; Teresa, K.; Adugna, A.; Geremew, T.; Shimelis, M.; Solomon, S.; Legesse, T.; Gilman, K.H.S. Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis at Asella Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia: Ten Years’ Retrospective Aggregated Data. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.K.; Karanja, S.; Karama, M. Factors associated with tuberculosis treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients attending tuberculosis treatment centers in 2016–2017 in Mogadishu, Somalia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017, 28, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Padmapriyadarsini, C.; Narendran, G.; Swaminathan, S. Dignosis and Treatment of Tuberculosis in HIV co-infected patients. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seddon, J.A.; Hesseling, A.C.; Willemse, M.; Donald, P.R.; Schaaf, H.S. Culture-confirmed multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children: Clinical features, treatment and outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlir, D.V.; Getahun, H.; Sanne, I.; Nunn, P. Opportunities and challenges for HIV care in overlapping HIV and TB epidemics. JAMA 2008, 300, 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Vasankari, T.; Holmström, P.; Ollgren, J.; Liippo, K.; Kokki, M.; Ruutu, P. Risk factors for poor tuberculosis treatment outcome in Finland: A cohort study. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramose, J.M.; Reyes, F.; Facin, R. Surgical lymph biopsies in a rural Ethiopian hospital: Histopathologic diagnoses and clinical characteristics. Ethiop. Med. J. 2008, 46, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ayeno, H.D.; Regasa, B.M.; Lenjisa, J.L.; Umeta, G.T.; Woldu, M.A. A three Years Tuberculosis Treatment OutCome at Adama Hospital of Medical College, South East Ethiopia, A retrospective cross-sectional analysis. IJPBS 2014, 2, 2347–4785. [Google Scholar]

- Mesay, H.D.; Daniel, G.D.; Bernt, L. Trends of tuberculosis case notification and treatment outcomes in the Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia: Ten-year retrospective trend analysis in urban–rural settings. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114225. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 620 | 55.3 |

| Female | 502 | 44.7 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 748 | 66.7 |

| Rural | 374 | 33.3 |

| Age in years | ||

| 0–14 | 101 | 9 |

| 15–24 | 362 | 32.3 |

| 25–34 | 328 | 29.2 |

| 35–44 | 172 | 15.3 |

| 45–54 | 74 | 6.6 |

| 55–64 | 50 | 4.5 |

| ≥65 | 35 | 3.1 |

| Microscopy profile of TB | ||

| PTB+ | 319 | 28.4 |

| PTB− | 352 | 31.4 |

| EPTB | 452 | 40.2 |

| Category of TB patients | ||

| New cases | 1064 | 94.8 |

| Relapse cases | 48 | 4.3 |

| Treatment after failure | 2 | 0.2 |

| Transferred cases | 8 | 0.7 |

| Died | 54 | 4.7 |

| HIV test result | ||

| Unknown | 6 | 0.5 |

| Positive | 238 | 21.2 |

| Negative | 878 | 78.3 |

| Variables | Successful | Unsuccessful | Total N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cured N (%) | Completed N (%) | Died N (%) | Defaulter N (%) | Failure N (%) | |||

| Sex | Male | 172 (27.7) | 401 (64.7) | 28 (4.5) | 18 (2.9) | 1 (0.2) | 620 (55.3) |

| Female | 112 (22.3) | 352 (70.1) | 25 (5) | 11 (2.2) | 2 (0.4) | 502 (44.7) | |

| Residence | Urban | 183 (24.5) | 524 (70.1) | 27 (3.6) | 13 (1.7) | 1 (0.1) | 748 (66.7) |

| Rural | 101 (27) | 229 (61.2) | 26 (7) | 16 (4.3) | 2 (0.5) | 374 (33.3) | |

| Age | 0–14 | 9 (8.9) | 88 (87.1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 101 (9) |

| 15–24 | 111 (30.7) | 231 (63.8) | 9 (2.4) | 10 (2.8) | 1 (0.3) | 362 (32.3) | |

| 25–34 | 98 (29.9) | 211 (64.3) | 14 (4.3) | 5 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 328 (29.2) | |

| 35–44 | 32 (18.6) | 12 (70.3) | 12 (7) | 7 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 172 (15.3) | |

| 45–54 | 19 (25.6) | 45 (60.8) | 8 (10.8) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 74 (6.6) | |

| 55–64 | 8 (16) | 31 (62) | 7 (14) | 4 (8) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (4.5) | |

| ≥65 | 7 (20) | 26 (74.3) | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (3.1) | |

| Microscopy profile of TB | PTB+ | 278 (87.1) | 12 (3.8) | 15 (4.7) | 13 (4.1) | 1 (0.3) | 319 (28.4) |

| PTB− | 4 (1.1) | 324 (92.1) | 20 (5.7) | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 352 (31.4) | |

| EPTB | 2 (0.4) | 417 (92.5) | 18 (4) | 12 (2.7) | 2 (0.4) | 451 (40.2) | |

| HIV status | Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.5) |

| Positive | 40 (16.8) | 151 (63.4) | 35 (15) | 11 (4.6) | 1 (0.4) | 238 (21.2) | |

| Negative | 244 (27.8) | 596 (68) | 18 (2) | 18 (2) | 2 (0.2) | 878 (78.3) | |

| Overall Total | 284 (25.3) | 753 (67.1) | 53 (4.7) | 29 (2.6) | 3 (0.3) | 1122 (100) | |

| Treatment Outcome | Year | Total (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||

| Cured (%) | 50 (20.8%) | 97 (26.8%) | 67 (23.6%) | 57 (30%) | 13 (33.3%) | 284 (25.3) |

| Treatment completed (%) | 183 (76.3%) | 242 (66.9%) | 197 (67.7%) | 110 (57.8%) | 21 (53.8%) | 753 (67.1) |

| Successful | ||||||

| Total (%) | 233 (97%) | 339 (93.6%) | 264 (90.7%) | 167 (87.9%) | 34 (87.2%) | 1037 (92.4) |

| Died (%) | 6 (2.5%) | 9 (2.5%) | 19 (6.5%) | 15 (7.9%) | 4 (10.3%) | 53 (4.7) |

| Defaulted (%) | 1 (0.4%) | 13 (3.6%) | 6 (2.1%) | 8 (4.2%) | 1 (2.6%) | 29 (2.6) |

| Treatment Failure (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) |

| Unsuccessful Total (%) | 7 (2.9%) | 23 (6.4%) | 27 (9.3%) | 23 (12.1%) | 5 (12.8%) | 85 (7.6) |

| Overall Total (%) | 240 (21.4) | 362 (32.3) | 291 (25.9) | 190 (16.9) | 39 (3.5) | 1122 (100) |

| Variables | Total No. | Treatment Outcome | COR | AOR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successful (%) | Unsuccessful (%) | ||||||

| Residence | |||||||

| Urban | 748 | 707 (63) | 41 (3.7) | 2.29 (1.47, 3.58) | 0.00 | 1.43 (0.27,0.67) | 0.00 |

| Rural | 374 | 330 (29.4) | 44 (3.9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| HIV status | |||||||

| Positive | 238 | 191 (17) | 47 (4.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Negative | 884 | 846 (75.4) | 38 (3.4) | 1.34 (0.11, 0.28) | 0.00 | 5.47 (3.47, 8.63) | 0.00 |

| Types of TB | |||||||

| PTB+ | 319 | 290 (25.8) | 29 (2.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| PTB− | 352 | 328 (29.3) | 24 (2.1) | 1.31 (0.78, 2.21) | 0.11 | 0.95 (0.55, 1.65) | 0.87 |

| EPTB | 451 | 419 (37.3) | 32 (2.9) | 0.96 (0.59,1.70) | 0.18 | 0.70 (0.26, 1.86) | 0.478 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsegaye, B.; Bedewi, Z.; Asnake, S. The Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis Patients at Adare General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia (A Five-Year Retrospective Study). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9110262

Tsegaye B, Bedewi Z, Asnake S. The Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis Patients at Adare General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia (A Five-Year Retrospective Study). Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2024; 9(11):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9110262

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsegaye, Bizunesh, Zufan Bedewi, and Solomon Asnake. 2024. "The Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis Patients at Adare General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia (A Five-Year Retrospective Study)" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 9, no. 11: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9110262

APA StyleTsegaye, B., Bedewi, Z., & Asnake, S. (2024). The Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis Patients at Adare General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia (A Five-Year Retrospective Study). Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 9(11), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9110262