Hygiene and Health Coaching for Community Readiness to Perform the Hajj during an Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

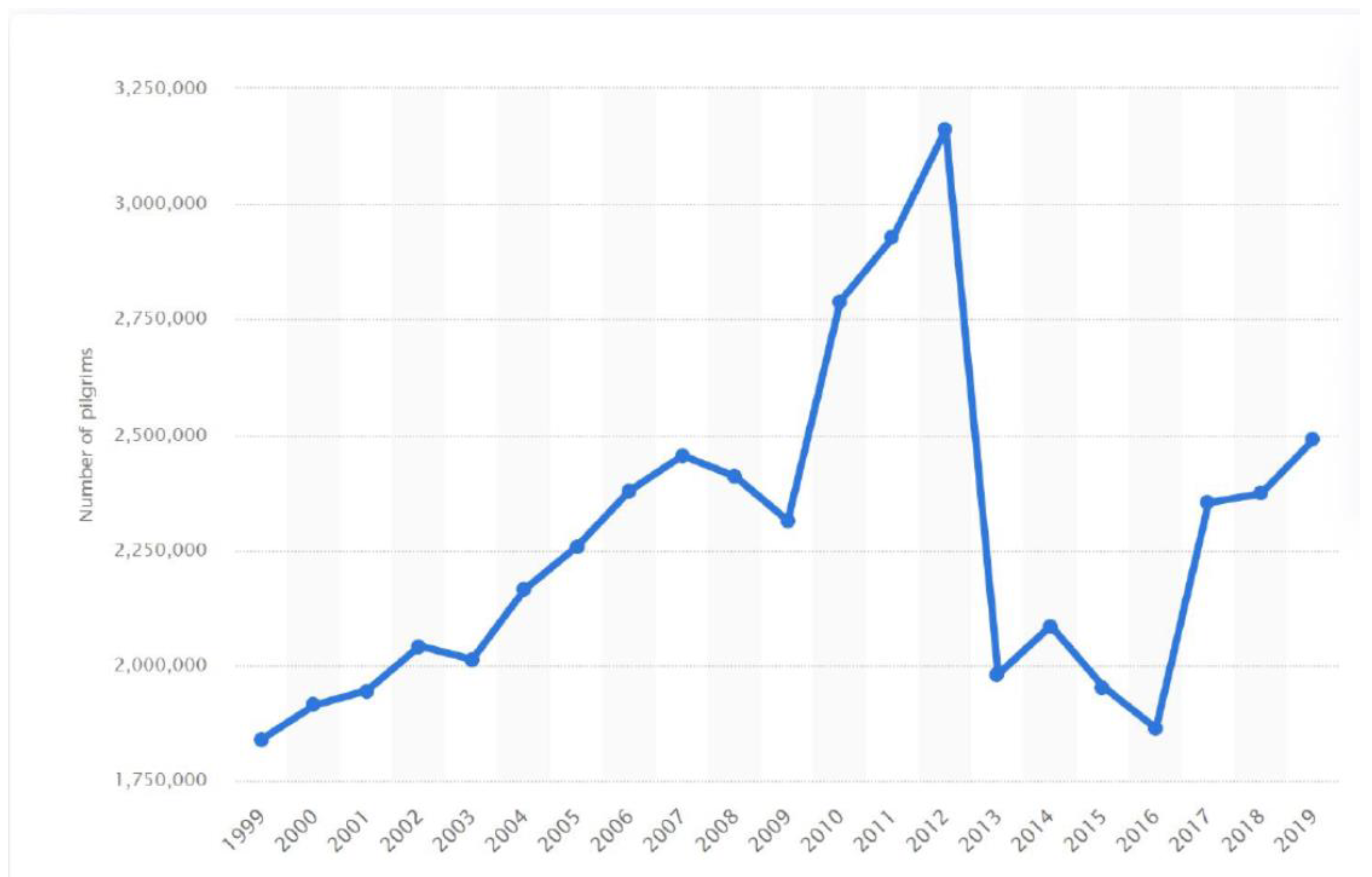

1. Introduction

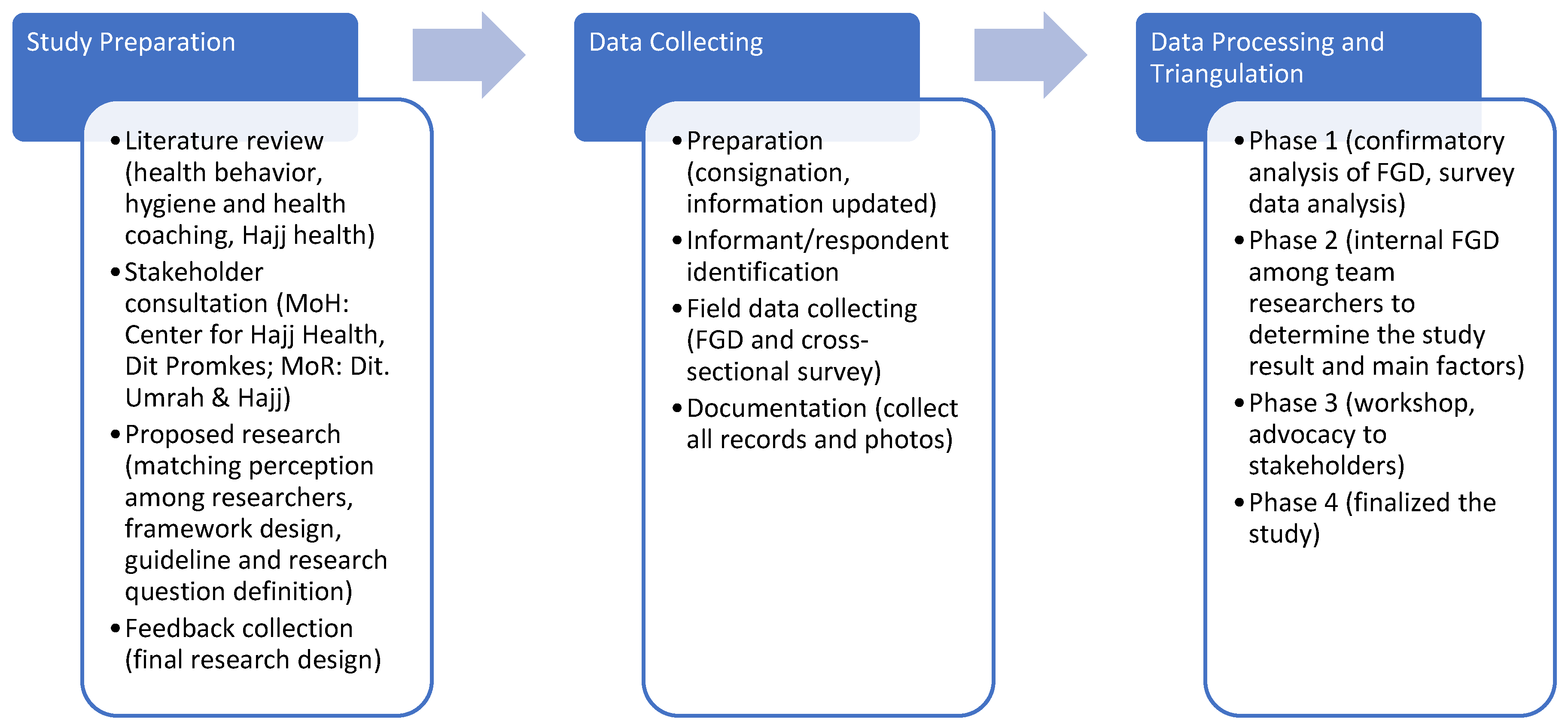

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge Level of Hajj Congregants’ Attitudes and Behaviors towards Health Development

3.1.1. Characteristics of Respondents

3.1.2. Relationship Characteristics, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior Coaching

3.2. Implementation of Hygiene and Health Coaching for Indonesian Hajj Pilgrims during the COVID-19 Period

“….the use of telemedicine helps support the policies of Implementation of Restrictions on Social Activities including health services in health care facilities…. Pilgrims and their families who are able to use telemedicine have a benefit from these health services…. however, the results of examinations of pilgrims using telemedicine cannot be accessed by hajj health workers, making it difficult to monitor the health developments of pilgrims during the waiting period in the pandemic.…”(Informant from Health Office in Bandung City, West Java).

“….the health office and the Puskesmas in collaboration with KBIHU have involved TKHI candidates for health education which we conduct through webinars, some at the city level, some at the puskesmas level with TKHI, for fitness measurement we socialize it with limited face-to-face meetings conducted by several people (maximum 20 people) by implementing strict health protocols, and we do it together with prospective TKHI whose results will be inputted to Siskohatkes….”(Informant from Health Office in Tangerang Selatan City, Banten).

“….hygiene and health coaching during a pandemic is carried out online, both in the form of workshops, fitness measurements and evaluations…. during the COVID-19 pandemic physical fitness measurements were still carried out by pilgrims using the Rockport method, walking for 6 min using the Fitness Information System (SIPGAR) application.... the results obtained from 5 batches were 35,000 pilgrims in 34 provinces. There are around 26,000 pilgrims with very good results, 3612 with good conditions, 8670 enough, 8196 lacking, 8410 very lacking, 3619 pilgrims not fit….”(Informant from Directorate of Occupational Health and Sport, Ministry of Health).

“….it’s rather difficult to use the SIPGAR application because there are so many things that have to be filled in and then you have to use an email while not all congregations have email and the Android application also doesn’t necessarily work because they have to log in, so it’s really not very effective….”(Informant from Health Office in Tangerang Selatan City, Banten).

“….utilization of UKBM is usually carried out under normal conditions, health coaching is carried out by utilizing Posbindu 4 times a year, but during a pandemic it cannot be used because there is a ban on gatherings….. Posbindu is only used by the PTM program, as well as home visits during a pandemic cannot be carried out regarding pandemic policies….”(Informant from Health Office in Gresik City, East Java).

“….the counseling during this pandemic is via WhatsApp or Vlog, so we often send videos from Youtube for those counseling via the group….”(Informant from Public Health Center in Gresik City, East Java).

“….Yes, each Puskesmas has its WA group, so any information that comes to us, be it in the form of a poster or in the form of a video vlog, we will immediately forward it to the pilgrim group….”(Informant from Health Office in Medan City, North Sumatera).

“….in the process of health coaching and counseling during a pandemic, the Puskesmas carried out health rituals starting from health checks, supporting examinations and referrals, but the implementation had not been integrated across programs because the budgeting of health for Hajj program was not centered in one activity in the surveillance section…. KBIHU cooperates with the Puskesmas in carrying out Hajj rituals…. During the pandemic, the Hajj rituals were also carried out online and materials for the Hajj rituals were sent via e-mail or social media to the pilgrims….”(Informant from Health Office in the Lombok Timur District, West Nusa Tenggara).

“….for health education, there was quite a lot of health information given to pilgrims, but the material presented varied from one region to another…. information on guidelines for the prevention and transmission of COVID-19 for officers and pilgrims has not been fully disseminated…. health information media use more social media such as WhatsApp and YouTube in the form of limited short videos or vlogs….”(Informant from Health Office in the Gowa District, South Sulawesi).

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboul-Enein, F.; Turkistani, Y.; Barnawi, O. The Role of Ambient Temperature and Plasma Osmolarity on Clinical Outcomes of Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients during Hajj. J. Cardiol. Res. Rev. Rep. 2020, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascoura, I.E. Impact of Pilgrimage (Hajj) on the Urban Growth of the Mecca. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2013, 3, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhiah, N.; Nor, M.; Mohamed, R.; Wahab, A.; Osman, O. The Construction of a Measuring Tool for the Health Management Research on Malaysian Hajj Pilgrim: The Focus Group Discussion (FGD) Approach. In Proceedings of the 2nd UMM International Qualitative Research Conference, Penang, Malaysia, 24–26 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rustika, R.; Oemiati, R.; Asyary, A.; Rachmawati, T. An Evaluation of Health Policy Ifiguremplementation for Hajj Pilgrims in Indonesia. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchtar, M. Pengaruh Penyakit Kardiovaskular Terhadap Kematian Jemaah Haji Asal Jawa Barat Embarkasi Halim Perdana Kusumah Tahun 1998. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitas Indonesia, Jawa Barat, Indonesia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, R.; Akhriani, H.N. Determinan Activity of Daily Living (ADL) Elderly Tresna Werdha Nursing Home (PSTW) Spesial in Yog-yakarta. J. Ultim. Public Health 2018, 2, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, M.D.; Hasan, H.; Deris, Z.Z.; Arifin, W.N.; Baaba, A.A. Hajj Pilgrimage amidst COVID-19 pandemic: A review. Bangladesh J. Med. Sci. 2021, 20, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basahel, S.; Alsabban, A.; Yamin, M. Hajj and Umrah management during COVID-19. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2021, 13, 2491–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, V.-T.; Gautret, P.; Memish, Z.A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A. Hajj and Umrah Mass Gatherings and COVID-19 Infection. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2020, 7, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustika, R.; Kusnali, A.; Pranata, S.; Puspasari, H.W.; Oemiati, R.; Suharmiati. Evaluasi Implementasi Istithaah Kesehatan Haji di Indonsia; Ltibang Kemkes RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rustika, R.; Puspasari, H.W.; Syam, P.; Oemiyati, R.; Musadad, D.A.; Ristrini, R. Tingkat Pengetahuan, Sikap, dan Tindakan Jemaah Haji Terkait Istithaah Kesehatan di Indonesia. Bul. Penelit. Sist. Kesehat 2019, 22, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Alshammari, S.M.; Almutiry, W.K.; Gwalani, H.; Algarni, S.M.; Saeedi, K. Measuring the impact of suspending Umrah, a global mass gathering in Saudi Arabia on the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 2021, 1–26, in-press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, S.H.; Ahmed, Y.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Memish, Z.A. The Hajj pilgrimage during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: Event hosting without the mass gathering. J. Travel Med. 2020, 28, taaa194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althobaity, H.M.; Alharthi, R.A.S.; Altowairqi, M.H.; Alsufyani, Z.A.; Aloufi, N.S.; Altowairqi, A.E.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Alzahrani, A.K.; Abdel-Moneim, A.S. Knowledge and awareness of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus among Saudi and Non-Saudi Arabian pilgrims. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Beuffort, L. Managing Health Programs and Project; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kementerian Kesehatan RI. Profil Kesehatan Indonesia Tahun 2019 Sekretariat Jenderal, Kementerian Kesehatan RI; Kementerian Kesehatan RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor Kementerian Agama Kabupaten Kebumen. KUA Petanahan Gelar Pembinaan Kesehatan Calon Jamaah Haji; Kantor Kementerian Agama Kabupaten Kebumen: Jawa Tengah, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Secretariat of The Republic of Indonesia. Gov’t Announces 2022 Hajj Preparation; Cabinet Secretariat of The Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Azizah, N. Kemenag Siapkan Pola Baru Manasik Haji di Tengah Pandemi; Media Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Supriyatno, H.; Ratusan, C.J.H. Kota Probolinggo Ikuti Pembinaan dan Perencanaan Pemeriksaan Kesehatan; Harian Bhirawa: Surabaya, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Afnita, J.; Putro, K.Z. Model Pembelajaran Daring untuk Meningkatkan Keaktifan Mahasiswa Pendidikan Islan Anak Usia Dini. J. Ilm. Potensia 2021, 6, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Haryani, S.; Sahar, J.; Sukihananto. The Influence of Direct Health Education and Using Mass Media to Treatment of Hyper-tension at the Age of Adult. J. Keperawatan. Indones. 2016, 19, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yezli, S.; Assiri, A.M.; Alhakeem, R.F.; Turkistani, A.M.; Alotaibi, B. Meningococcal disease during the Hajj and Umrah mass gatherings. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, A.; Mortazavi, S.M.; Shamspour, N.; Shushtarizadeh, N. Health Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Among Iranian Pilgrims. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2015, 17, e12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroline, C.; Lestari, E.P. Adakah Relasi Antara Modal Sosial, dan Pertumbuhan Ekonomi Jawa Tengah? Indic. J. Econ. Bus. 2020, 2, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistiyawati, I. Hubungan antara Pekerjaan, Pendapatan, Pengetahuan, Sikap Lansia dengan Kunjungan ke Posyandu Lansia. Str. J. Ilm. Kesehat 2010, 8, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Saridi, A.S.; Wibowo, Y.S.; Anggela, E. Strategi Komunikasi, Inovasi, dan Mitigasi Penyelenggaraan Ibadah Haji dan Umrah di Masa Pandemi. J. SMART 2021, 7, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S. Media Komunikasi dalam Mendukung Penyebarluasan Informasi Penanggulangan Pandemi COVID-19. Maj. Semi. Ilm. Pop. Komun. Massa 2021, 2, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Alfelali, M.; Koul, P.A.; Rashid, H. Pandemic Viruses at Hajj: Influenza and COVID-19. In Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1249–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Alsharif, S.A.; Garnan, M.A.; Tashani, M.; BinDhim, N.F.; Heywood, E.A.; Booy, R.; Wiley, K.E.; Rashid, H. Hajj Research Group the Impact of Receiving Pretravel Health Advice on the Prevention of Hajj-Related Illnesses among Australian Pilgrims: Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e10959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfelali, M.; Haworth, E.A.; Barasheed, O.; Badahdah, A.-M.; Bokhary, H.; Tashani, M.; Azeem, M.I.; Kok, J.; Taylor, J.; Barnes, E.H.; et al. Facemask against viral respiratory infections among Hajj pilgrims: A challenging cluster-randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdi, H.; Alqahtani, A.; Barasheed, O.; Alemam, A.; AlHakami, M.; Gadah, I.; Alkediwi, H.; Alzahrani, K.; Fatani, L.; Dahlawi, L.; et al. Hand Hygiene Knowledge and Practices among Domestic Hajj Pilgrims: Implications for Future Mass Gatherings Amidst COVID-19. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable (N = 2425) | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Banten | 129 | 5.3 |

| West Java and Central Java | 616 | 25.4 | |

| East Java | 999 | 41.2 | |

| South Kalimantan | 100 | 41.2 | |

| West Nusa Tenggara | 147 | 6.1 | |

| South Sulawesi | 178 | 7.3 | |

| North Sumatera | 256 | 10.6 | |

| Age | <40 years | 218 | 9.0 |

| 40–60 years | 1576 | 65.0 | |

| >60 years | 631 | 26.0 | |

| Sex | Male | 1043 | 43.0 |

| Female | 1382 | 57.0 | |

| Education | High | 1867 | 77.0 |

| Moderate | 170 | 7.0 | |

| Low | 388 | 16.0 | |

| Occupation | Works | 2042 | 84.2 |

| Does not work | 383 | 15.8 | |

| COVID-19 Knowledge | Fair | 2389 | 98.5 |

| Poor | 36 | 1.5 | |

| Hygiene and Health Coaching Knowledge | Fair | 1553 | 64.0 |

| Poor | 872 | 36.0 | |

| Able to Access Coaching Material via YouTube | Yes | 1151 | 47.5 |

| No | 1274 | 52.5 | |

| Have Previously Taken Health Coaching | Already | 1914 | 78.9 |

| Not Yet | 511 | 21.1 | |

| Know Disease Risk in the KSA | Yes | 1483 | 61.1 |

| No | 942 | 38.8 | |

| Health Risk | High | 2173 | 89.6 |

| Low | 252 | 10.4 | |

| Do Fitness Activity | Yes | 2395 | 98.8 |

| No | 30 | 1.2 | |

| Face-to-face Coaching Session | Yes | 1200 | 49.5 |

| No | 1225 | 50.5 | |

| Online Coaching Session | Yes | 1699 | 70.0 |

| No | 726 | 30.0 | |

| Blended Coaching Sessions | Yes | 1337 | 55.1 |

| No | 1088 | 44.9 | |

| Previous Coaching Frequency | >8 times | 751 | 30.9 |

| 4–8 times | 737 | 30.4 | |

| <4 times | 937 | 38.7 | |

| Variable | Face-to-Face Coaching (%) | Online Coaching (%) | Blended Coaching (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p-Value | Yes | No | p-Value | Yes | No | p-Value | ||

| Age Group | <40 years | 81.9 | 18.1 | 0.01 | 69.0 | 31.0 | 0.87 | 56.0 | 44.0 | 0.19 |

| 40–60 years | 73.4 | 26.6 | 0.95 | 78.4 | 21.6 | 0.00 | 56.7 | 43.3 | 0.01 | |

| >60 years | 73.6 | 26.4 | 69.7 | 30.3 | 50.8 | 49.2 | ||||

| Sex | Male | 76.9 | 23.1 | 0.01 | 74.1 | 25.1 | 0.70 | 57.0 | 43.0 | 0.11 |

| Female | 72.3 | 27.7 | 75.6 | 24.4 | 53.7 | 46.3 | ||||

| Education | High | 77.2 | 28.2 | 0.00 | 77.1 | 22.9 | 0.01 | 54.6 | 45.4 | 0.14 |

| Moderate | 80.8 | 19.2 | 0.01 | 65.9 | 34.1 | 0.00 | 52.1 | 47.9 | 0.57 | |

| Low | 83.2 | 16.8 | 70.5 | 29.5 | 58.8 | 41.2 | ||||

| Occupation | Works | 74.3 | 25.7 | 0.85 | 76.5 | 23.5 | 0.00 | 56.0 | 44.0 | 0.04 |

| Doesn’t work | 73.9 | 26.1 | 68.7 | 31.3 | 50.4 | 49.6 | ||||

| COVID-19 Knowledge | Fair | 74.3 | 25.7 | 0.56 | 75.7 | 24.3 | 0.00 | 55.5 | 44.5 | 0.01 |

| Poor | 69.4 | 30.6 | 44.4 | 55.6 | 33.3 | 66.7 | ||||

| Hygiene and Health Coaching Knowledge | Fair | 77.5 | 22.5 | 0.00 | 82.1 | 17.9 | 0.00 | 61.5 | 38.5 | 0.00 |

| Poor | 68.6 | 31.4 | 63.1 | 36.9 | 43.8 | 56.2 | ||||

| Able to Access Coaching Theory via YouTube | Yes | 73.1 | 26.9 | 0.21 | 88.7 | 11.3 | 0.00 | 64.1 | 35.9 | 0.00 |

| No | 75.4 | 24.6 | 63.1 | 36.9 | 47.0 | 53.0 | ||||

| Have Previously Taken Health Coaching | Already | 77.4 | 22.6 | 0.00 | 77.2 | 22.8 | 0.00 | 57.8 | 42.2 | 0.00 |

| Not Yet | 62.4 | 37.6 | 68.1 | 31.9 | 45.0 | 55.0 | ||||

| Know Disease Risk in the KSA | Yes | 76.1 | 23.9 | 0.01 | 80.9 | 19.1 | 0.00 | 60.1 | 39.9 | 0.00 |

| No | 71.3 | 28.7 | 66.3 | 33.7 | 47.3 | 52.7 | ||||

| Hygiene and Healthy Lifestyle Attitude | Fair | 74.1 | 25.9 | 0.70 | 76.6 | 23.4 | 0..00 | 56.2 | 43.8 | 0.00 |

| Poor | 75.4 | 24.6 | 63.9 | 36.1 | 45.6 | 54.4 | ||||

| Do Fitness Activity | Yes | 74.4 | 25.6 | 0.21 | 75.6 | 24.4 | 0.00 | 55.4 | 44.6 | 0.03 |

| No | 63.3 | 36.7 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 33.3 | 66.7 | ||||

| Previously-taken Coaching Frequency | >8 times | 82.8 | 17.2 | 0.00 | 72.2 | 27.8 | 0.12 | 59.8 | 40.2 | 0.00 |

| 4–8 times | 77.5 | 22.5 | 0.00 | 78.0 | 22.0 | 0.25 | 59.2 | 40.8 | 0.00 | |

| <4 times | 64.9 | 35.1 | 75.6 | 24.4 | 48.2 | 51.8 | ||||

| Variable | Face-to-Face Coaching | Online Coaching | Blended Coaching | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | <40 years | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.90 | 1.04 | 0.75 | 1.44 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 1.10 |

| 40–60 years | 1.01 | 0.82 | 1.24 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.95 | |

| >60 years | ||||||||||

| Sex | Male | 1.27 * | 1.06 | 1.53 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 0.97 | 1.35 |

| Female | ||||||||||

| Education | High | 1.94 * | 1.46 | 2.57 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.91 | 1.19 | 0.95 | 1.48 |

| Moderate | 1.65 | 1.11 | 2.46 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.66 | 1.24 | |

| Low | ||||||||||

| Occupation | Works | 1.02 | 0.80 | 1.31 | 1.49 * | 1.17 | 1.89 | 1.25 * | 1.01 | 1.56 |

| Doesn’t work | ||||||||||

| COVID-19 Knowledge | Fair | 0.78 | 0.38 | 1.60 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.81 |

| Poor | ||||||||||

| Hygiene and Health Coaching Knowledge | Fair | 1.58 * | 1.31 | 1.90 | 2.69 * | 2.22 | 3.24 | 2.05 | 1.73 | 2.42 |

| Poor | ||||||||||

| Able to Access Coaching Materials via YouTube | Yes | 1.13 | 0.94 | 1.35 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.59 |

| No | ||||||||||

| Have Previously Taken Health Coaching | Already | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.73 |

| Not Yet | ||||||||||

| Know Disease Risk in the KSA | Yes | 0.78 | 0.65 | 0.94 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.70 |

| No | ||||||||||

| Hygiene and Healthy Lifestyle Attitude | Fair | 0.94 | 0.69 | 1.27 | 1.85 * | 1.40 | 2.43 | 1.53 * | 1.18 | 1.99 |

| Poor | ||||||||||

| Do Fitness Activities | Yes | 0.59 | 0.28 | 1.26 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.189 | 0.86 |

| No | ||||||||||

| Previous Coaching Frequency | >8 times | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 1.19 | 0.96 | 1.48 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.76 |

| 4–8 times | 1.86 * | 1.50 | 2.32 | 1.15 | 0.91 | 1.44 | 1.55 * | 1.28 | 1.89 | |

| <4 times | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Indharty, R.S.; Rustika; Sylvana, B.; Susilo, L.M.; Rachmawati, T.; Zuchdi, Z.; Cahyono, I.; Hamdani, M.I.S.; Kusnali, A.; Musadad, D.A.; et al. Hygiene and Health Coaching for Community Readiness to Perform the Hajj during an Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8020090

Indharty RS, Rustika, Sylvana B, Susilo LM, Rachmawati T, Zuchdi Z, Cahyono I, Hamdani MIS, Kusnali A, Musadad DA, et al. Hygiene and Health Coaching for Community Readiness to Perform the Hajj during an Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2023; 8(2):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8020090

Chicago/Turabian StyleIndharty, Rr Suzy, Rustika, Budi Sylvana, Liliek Marhaendo Susilo, Tety Rachmawati, Zolaiha Zuchdi, Imron Cahyono, Mohammad Imran Saleh Hamdani, Asep Kusnali, Dede Anwar Musadad, and et al. 2023. "Hygiene and Health Coaching for Community Readiness to Perform the Hajj during an Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 8, no. 2: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8020090

APA StyleIndharty, R. S., Rustika, Sylvana, B., Susilo, L. M., Rachmawati, T., Zuchdi, Z., Cahyono, I., Hamdani, M. I. S., Kusnali, A., Musadad, D. A., Firdaus, M., Asyary, A., & Memish, Z. A. (2023). Hygiene and Health Coaching for Community Readiness to Perform the Hajj during an Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 8(2), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8020090