Hand Hygiene Practices and Promotion in Public Hospitals in Western Sierra Leone: Changes Following Operational Research in 2021

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.2.1. General Setting

2.2.2. Specific Setting

2.3. Study Population

2.4. HHSAF Tool

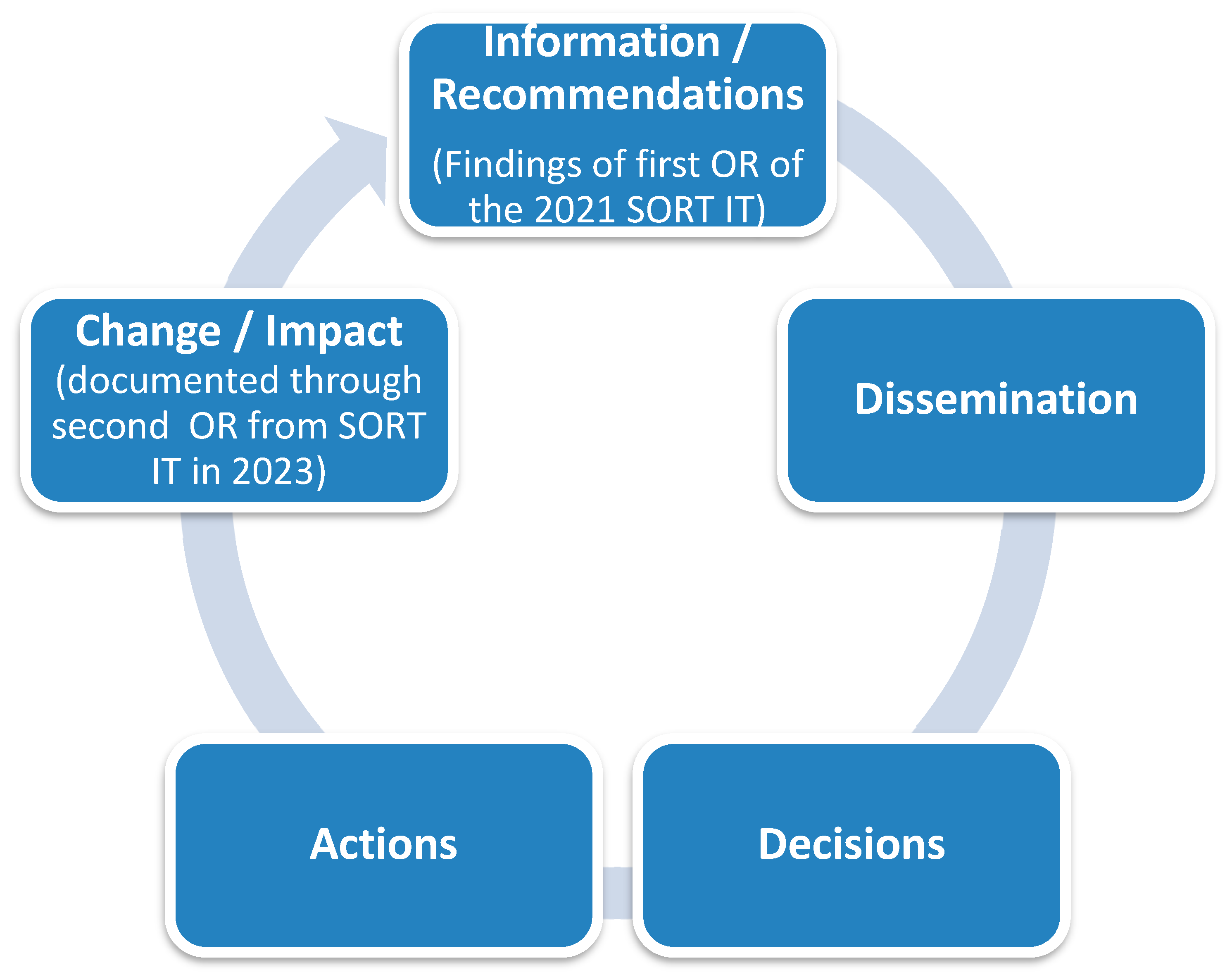

2.5. Information from Previous Operational Research, Dissemination Activities, Decisions, and Actions

2.6. Data Variables and Sources of Data

2.7. Data Analysis and Statistics

2.8. Institutional Review Board Statement

3. Results

3.1. Hospital Characteristics

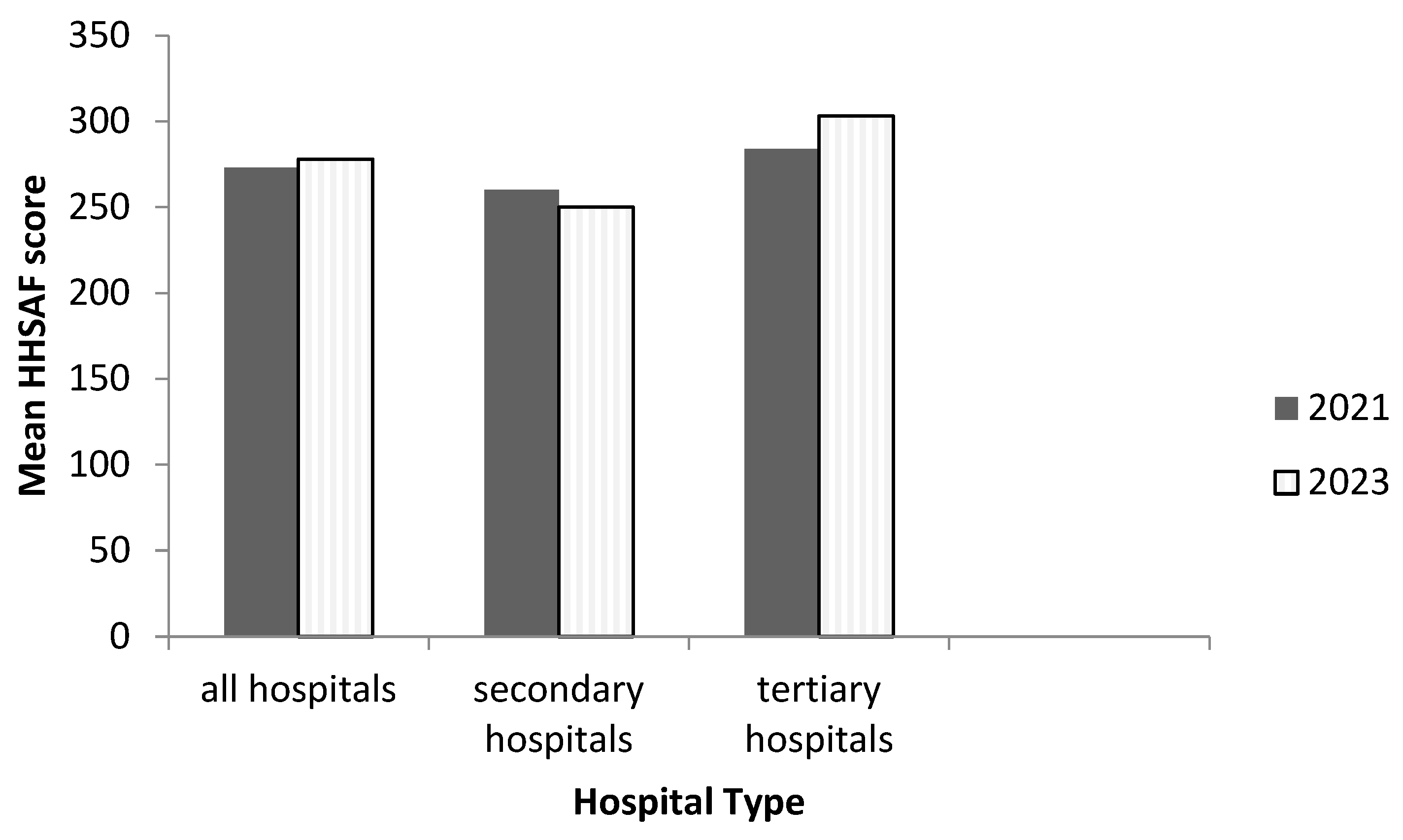

3.2. Changes in the Mean HHSAF Score, Overall, by Hospital Type and by Domain Wise

3.3. Change in Performance of Each Indicator under the Various Domains

3.3.1. System Change

3.3.2. Training and Education

3.3.3. Evaluation and Feedback

3.3.4. Reminders in the Workplace

3.3.5. Institutional Safety Climate

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Open Access Statement

References

- World Health Organization. Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide Clean Care Is Safer Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nejad, S.B.; Allegranzi, B.; Syed, S.B.; Ellisc, B.; Pittetd, D. Health-Care-Associated Infection in Africa: A Systematic Review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Hou, T.; Ma, H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, A.; Liu, Y.; Wen, J.; Yang, H.; et al. Impact of Healthcare-Associated Infections on Length of Stay: A Study in 68 Hospitals in China. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 2590563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Burriel, M.; Keys, M.; Campillo-Artero, C.; Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Gikas, A.; Palos, C.; López-Casasnovas, G. Impact of Multi-Drug Resistant Bacteria on Economic and Clinical Outcomes of Healthcare-Associated Infections in Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, E.; Damani, N. Healthcare-Associated Infections in Intensive Care Units: Epidemiology and Infection Control in Low-to-Middle Income Countries. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 9, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, C.; Schlaich, C.; Thompson, S. Healthcare-Associated Infections in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Hosp. Infect. 2013, 85, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, L.; O’Connell, N.H.; Dunne, C.P. Hand Hygiene-Related Clinical Trials Reported since 2010: A Systematic Review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016, 92, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftus, M.J.; Guitart, C.; Tartari, E.; Stewardson, A.J.; Amer, F.; Bellissimo-Rodrigues, F.; Lee, Y.F.; Mehtar, S.; Sithole, B.L.; Pittet, D. Hand Hygiene in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 86, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework 2010 Introduction and User Instructions; World Health Organization: Geneva Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Sanitation; Government of the Republic of Sierral Leone. National Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines; Ministry of Health and Sanitation: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2016.

- Ministry of Health and Sanitation; Government of Sierra Leone. Ebola Viral Disease Situation Report; Ministry of Health and Sanitation: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2015.

- Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR). AMR-SORT IT 2022 Annual Report. Progress, Achievements, Challenges; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoh, S.; Maruta, A.; Kallon, C.; Deen, G.F.; Russell, J.B.W.; Fofanah, B.D.; Kamara, I.F.; Kanu, J.S.; Kamara, D.; Molleh, B.; et al. How Well Are Hand Hygiene Practices and Promotion Implemented in Sierra Leone? A Cross-Sectional Study in 13 Public Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Sierra Leone. 2015 Population and Housing Census. Summary of Final Results; Statistics Sierra Leone: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund Sierra Leone. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/SLE#ataglance (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- The World Bank Sierra Leone. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/SL (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Statistics Sierra Leone; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Sierra Leone Multuple Indicator Cluster Survey 2017; Statistics Sierra Leone: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR). AMR-SORT IT Evidence Summaries: Communicating Research Findings. Available online: https://tdr.who.int/activities/sort-it-operational-research-and-training/communicating-research-findings (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Lakoh, S.; Firima, E.; Williams, C.E.E.; Conteh, S.K.; Jalloh, M.B.; Sheku, M.G.; Adekanmbi, O.; Sevalie, S.; Kamara, S.A.; Kamara, M.A.S.; et al. An Intra-COVID-19 Assessment of Hand Hygiene Facility, Policy and Staff Compliance in Two Hospitals in Sierra Leone: Is There a Difference between Regional and Capital City Hospitals? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataiyero, Y.; Dyson, J.; Graham, M. Barriers to Hand Hygiene Practices among Health Care Workers in Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Narrative Review. Am. J. Infect. Control 2019, 47, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.; Yang, S.J. The Evaluation of a Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy in Cambodian Hospitals. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittet, D. Improving Adherence to Hand Hygiene Practice: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, P. Hand Hygiene: Back to the Basics of Infection Control. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, M.P.; Carter, E.; Siddiqui, N.; Larson, E. Hand Hygiene Compliance in an Emergency Department: The Effect of Crowding. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uneke, C.J.; Ndukwe, C.D.; Oyibo, P.G.; Nwakpu, K.O.; Nnabu, R.C.; Prasopa-Plaizier, N. Promotion of Hand Hygiene Strengthening Initiative in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital: Implication for Improved Patient Safety in Low-Income Health Facilities. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 18, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmen, I.C.; Seneza, C.; Nyiranzayisaba, B.; Nyiringabo, V.; Bienfait, M.; Safdar, N. Improving Hand Hygiene Practices in a Rural Hospital in Sub-Saharan Africa. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamara, G.N.; Sevalie, S.; Molleh, B.; Koroma, Z.; Kallon, C.; Maruta, A.; Kamara, I.F.; Kanu, J.S.; Campbell, J.S.O.; Shewade, H.D.; et al. Hand Hygiene Compliance at Two Tertiary Hospitals in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in 2021: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoh, S.; Bangura, M.M.; Adekanmbi, O.; Barrie, U.; Jiba, D.F.; Kamara, M.N.; Sesay, D.; Jalloh, A.T.; Deen, G.F.; Russell, J.B.W.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the Utilization of HIV Testing and Linkage Services in Sierra Leone: Experience from Three Public Health Facilities in Freetown. AIDS Behav. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoh, S.; Jiba, D.F.; Baldeh, M.; Adekanmbi, O.; Barrie, U.; Seisay, A.L.; Deen, G.F.; Salata, R.A.; Yendewa, G.A. Impact of COVID-19 on Tuberculosis Case Detection and Treatment Outcomes in Sierra Leone. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsotakis, E.I.; Astrinaki, E.; Messaritaki, A.; Gikas, A. Implementation of Multimodal Infection Control and Hand Hygiene Strategies in Acute-Care Hospitals in Greece: A Cross-Sectional Benchmarking Survey. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegranzi, B.; Conway, L.; Larson, E.; Pittet, D. Status of the Implementation of the World Health Organization Multimodal Hand Hygiene Strategy in United States of America Health Care Facilities. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2014, 42, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, F.; Giacomelli, S.; Ceresetti, D.; Zotti, C.M. World Health Organization Framework: Multimodal Hand Hygiene Strategy in Piedmont (Italy) Health Care Facilities. J. Patient Saf. 2019, 15, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenmayer, K.; Msamba, V.-S.; Chilunda, F.; Kiologwe, J.C.; Seni, J. Impact of Hand Hygiene Intervention: A Comparative Study in Health Care Facilities in Dodoma Region, Tanzania Using WHO Methodology. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Sharma, M.; Koushal, V. Compliance to Hand Hygiene World Health Organization Guidelines in Hospital Care. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 127–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Omilabu, S.A.; Salu, O.B.; Oke, B.O.; James, A.B. The West African Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic 2014–2015: A Commissioned Review. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Information/Findings (Key Messages) | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Intermediate level of hand hygiene practices and promotion | Implement strategies to improve hand hygiene |

| No formalized patient engagement program | In addition to engaging healthcare workers on hand hygiene, we recommend the engagement of patients and relatives in hand hygiene promotion |

| No funding to support hand hygiene promotion, as many hospitals lack funding to support normal hospital activities | Hospital administrators should explore other sources of funding for sustaining local initiatives on hand hygiene practices and promotion |

| Limited hand hygiene resources for hand hygiene reminders in the workplace | We recommend hand hygiene posters at various places in hospitals, especially in hand hygiene stations |

| Lack of a system for the designation of hand hygiene champions or role models | Establish systems for recognizing hand hygiene champions and role models |

| To Whom | When | Where | Mode of Delivery * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical professionals and other healthcare workers | May to August 2022 | Official WhatsApp group of the Ministry of Health and four professional groups | Video of lightening presentation |

| Two national engagement meetings | May and November 2022 | Stakeholders from the Ministries of Health, Environment, and Agriculture | Technical PowerPoint presentation |

| Clinicians (around 80) | April 2022 and December 2022 | Three tertiary hospitals in the Western Area of Sierra Leone | Technical PowerPoint presentation |

| Hospital management of one tertiary hospital | October 2022 | One of the tertiary hospitals | Handout [18] and Elevator pitch |

| Decisions | Action Status ** | Details of Action (When and What) |

|---|---|---|

| Strengthen the distribution of hand hygiene posters and alcohol-based hand rub | Ongoing | By working with the national IPC program, a regular monthly supply of alcohol-based hand rub was maintained |

| Strengthen training of healthcare workers on hand hygiene | Ongoing | Orientation of new staff employed by the hospital on hand hygiene at any intake |

| Advocacy for budgetary support for hand hygiene | Ongoing | During the national engagement meeting in November 2023 |

| Advocacy to include hand hygiene in hospital improvement programs supported by partners | Completed | Hand hygiene was included in the implementation of quality IPC services supported by an implementing partner in three hospitals in December 2022 |

| Develop a policy for patient engagement on IPC | Ongoing | A written policy that shows how patients and relatives should be involved in hand hygiene practice and promotion is currently under development |

| Hospital Characteristics | Before | After | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Total | 13 | (100) | 13 | (100) |

| Bed Capacity | ||||

| ≤50 | 3 | (23.1) | 3 | (23.1) |

| 51–100 | 4 | (30.8) | 4 | (30.8) |

| 101–150 | 1 | (7.7) | 2 | (15.4) |

| 151–200 | 2 | (15.4) | 2 | (15.4) |

| >200 | 3 | (23.1) | 2 | (15.4) |

| Mean Bed Capacity | 111 | 132 | ||

| Staff Capacity | ||||

| ≤200 | 5 | (38.5) | 6 | (46.2) |

| 201–400 | 4 | (30.8) | 2 | (15.4) |

| 400–600 | 3 | (23.1) | 4 | (30.8) |

| ≥601 | 1 | (7.7) | 1 | (7.7) |

| Mean Staff Capacity | 277 | 241 | ||

| Units/Wards | ||||

| <10 | 1 | (7.7) | 5 | (38.5) |

| 10–20 | 8 | (61.5) | 6 | (46.2) |

| >20 | 4 | (30.8) | 2 | (15.4) |

| Level of care | ||||

| Tertiary | 7 | (53.8) | 7 | (53.8) |

| Secondary | 6 | (46.2) | 6 | (46.2) |

| Score Using HHSAF | Before | After | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| System change | 52.3 | (17.3) | 72.7 | (10.7) |

| Training and education | 66.9 | (17.4) | 50.0 | (17.6) |

| Evaluation and feedback | 54.0 | (13.4) | 53.9 | (11.6) |

| Reminders in the workplace | 50.0 | (18.1) | 43.2 | (16.0) |

| Institutional safety climate | 46.9 | (19.6) | 58.5 | (14.6) |

| Before | After | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Type | Hospital | SC | TE | EF | RW | ISC | HH Level | SC | TE | EF | RW | ISC | HH Level |

| Secondary | S1 | 35 | 80 | 48 | 55 | 50 | I/268 | 75 | 70 | 60 | 20 | 70 | I/295 |

| S2 | 40 | 35 | 58 | 50 | 30 | B/213 | 75 | 35 | 35 | 15 | 50 | B/210 | |

| S3 | 55 | 80 | 65 | 50 | 65 | I/315 | 80 | 35 | 40 | 25 | 50 | B/230 | |

| S4 | 80 | 50 | 45 | 70 | 30 | I/275 | 75 | 30 | 45 | 45 | 55 | B/250 | |

| S5 | 50 | 70 | 60 | 45 | 65 | I/290 | 85 | 50 | 65 | 48 | 65 | I/313 | |

| S6 | 75 | 50 | 68 | 63 | 50 | I/305 | 70 | 35 | 45 | 25 | 25 | B/200 | |

| Tertiary | T1 | 40 | 100 | 75 | 33 | 35 | I/283 | 70 | 80 | 60 | 50 | 85 | I/345 |

| T2 | 65 | 75 | 65 | 25 | 65 | I/295 | 80 | 35 | 65 | 50 | 65 | I/295 | |

| T3 | 55 | 65 | 35 | 15 | 40 | B/210 | 75 | 40 | 70 | 60 | 60 | I/305 | |

| T4 | 50 | 75 | 53 | 38 | 40 | I/255 | 70 | 60 | 55 | 50 | 55 | I/290 | |

| T5 | 30 | 55 | 35 | 68 | 25 | B/213 | 75 | 70 | 65 | 60 | 55 | I/325 | |

| T6 | 30 | 55 | 35 | 68 | 25 | B/213 | 40 | 40 | 58 | 50 | B/228 | ||

| T7 | 75 | 80 | 60 | 70 | 90 | I/375 | 75 | 70 | 55 | 55 | 75 | I/330 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamara, M.N.; Lakoh, S.; Kallon, C.; Kanu, J.S.; Kamara, R.Z.; Kamara, I.F.; Moiwo, M.M.; Kpagoi, S.S.T.K.; Adekanmbi, O.; Manzi, M.; et al. Hand Hygiene Practices and Promotion in Public Hospitals in Western Sierra Leone: Changes Following Operational Research in 2021. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8110486

Kamara MN, Lakoh S, Kallon C, Kanu JS, Kamara RZ, Kamara IF, Moiwo MM, Kpagoi SSTK, Adekanmbi O, Manzi M, et al. Hand Hygiene Practices and Promotion in Public Hospitals in Western Sierra Leone: Changes Following Operational Research in 2021. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2023; 8(11):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8110486

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamara, Matilda N., Sulaiman Lakoh, Christiana Kallon, Joseph Sam Kanu, Rugiatu Z. Kamara, Ibrahim Franklyn Kamara, Matilda Mattu Moiwo, Satta S. T. K. Kpagoi, Olukemi Adekanmbi, Marcel Manzi, and et al. 2023. "Hand Hygiene Practices and Promotion in Public Hospitals in Western Sierra Leone: Changes Following Operational Research in 2021" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 8, no. 11: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8110486

APA StyleKamara, M. N., Lakoh, S., Kallon, C., Kanu, J. S., Kamara, R. Z., Kamara, I. F., Moiwo, M. M., Kpagoi, S. S. T. K., Adekanmbi, O., Manzi, M., Fofanah, B. D., & Shewade, H. D. (2023). Hand Hygiene Practices and Promotion in Public Hospitals in Western Sierra Leone: Changes Following Operational Research in 2021. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 8(11), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8110486