Organizing Relational Complexity—Design of Interactive Complex Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

HCI and Complex Systems—A Call for a New Perspective

In order to formulate and address the critical issues that underlie a more trustful and beneficial relationship between humankind and technology.([9], p. 1230)

An ensemble of many elements which are interacting in a disordered way, resulting in robust organization and memory.([11], p. 57)

A system is said to be complex if there is a bidirectional non-separability between the identities of the parts and the identity of the whole.([10], p. 1159)

2. Materials and Methods

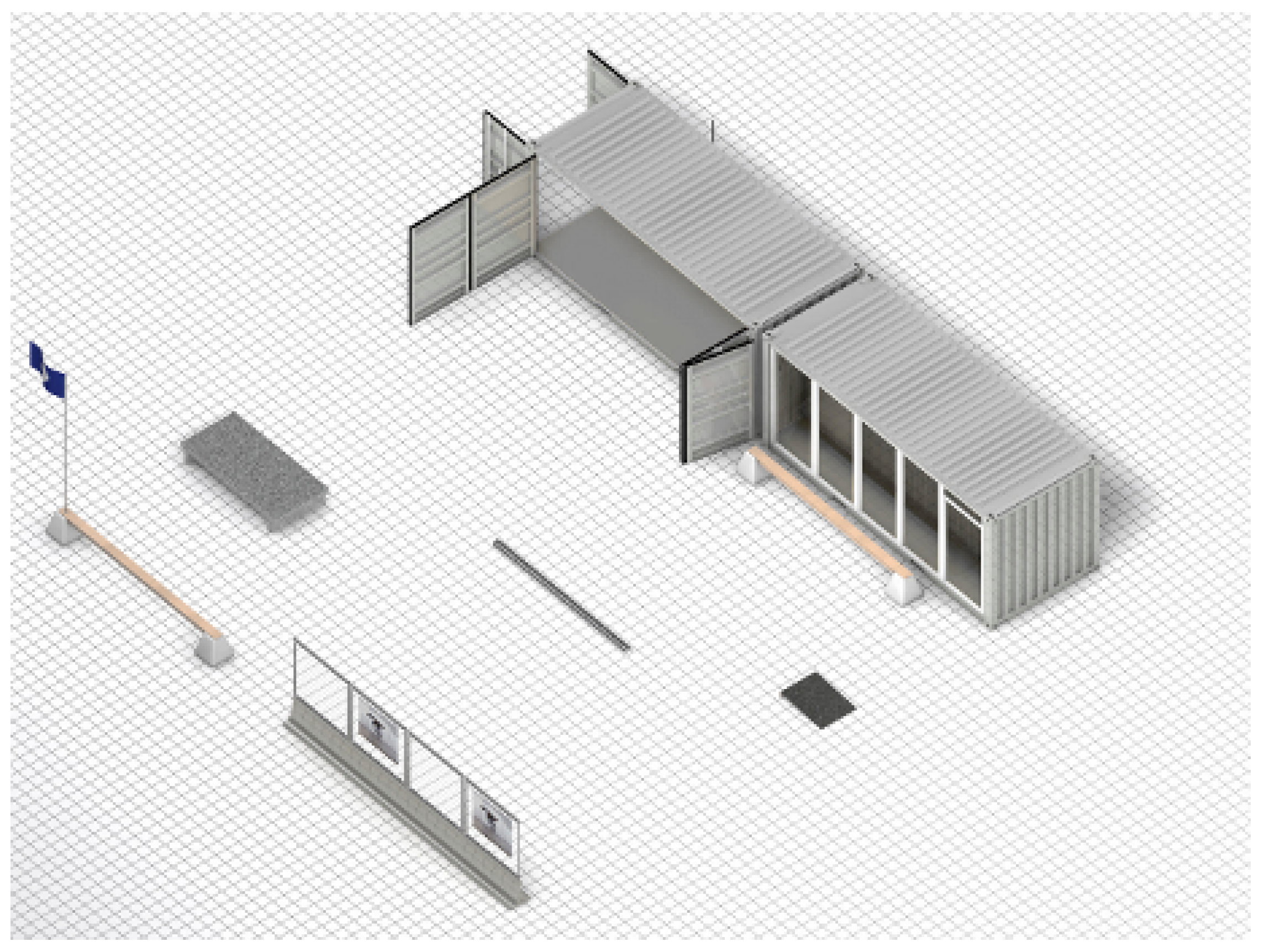

2.1. Case Study—How Skateboarding Culture Reveals Morinian Interactions and Agential Reality

Skateboarding Practices as Procedural Architecture

Due to the complexity of how a site is ’landed’, we can end up with an experiential gap in the affective power of an object. The way in which we experience an object can be based not on one but on a range of affects. This directs our evaluations and the way we find explanations to fill this gap. If we become disappointed by something, we find explanations to why it is disappointing, which as Sara Ahmed notes,To be affected by something is to evaluate that thing. Evaluations are expressed in how bodies turn toward things. To give value to things is to shape what is near us.([17], p. 31)

Can lead to a rage directed toward those that promised us happiness through the elevation of this or that object as being good. We become strangers, or affect aliens, in such moments.([17], p. 37)

3. Results

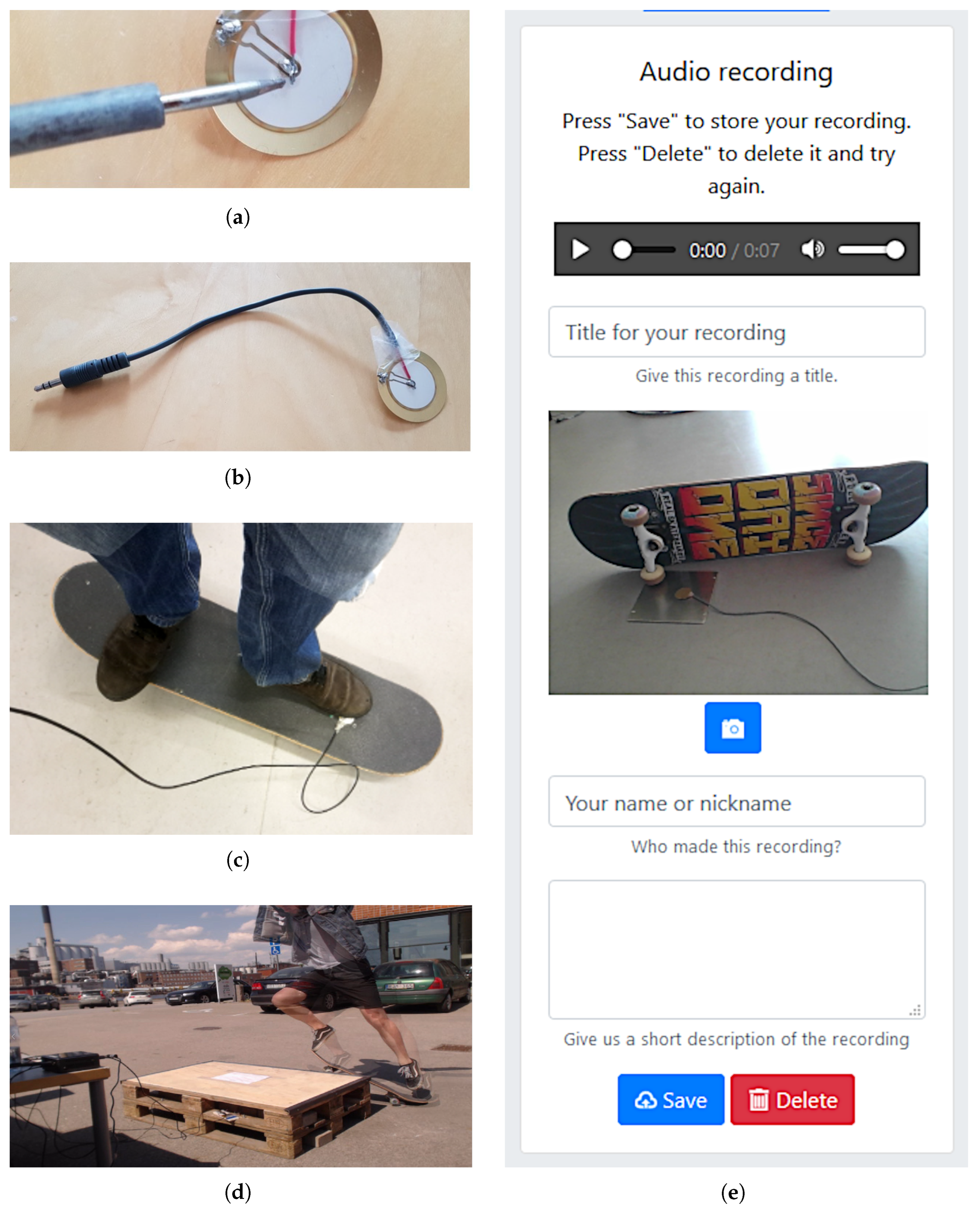

Skateboarding Interactions

“when I recorded sounds with the microphone, something felt odd, I now realized what. It sounds like rolling, yeah, that’s how it sounds when I roll. But not like when I hear it, but how it sounds inside my body. It’s like how it feels to roll”.

4. Discussion

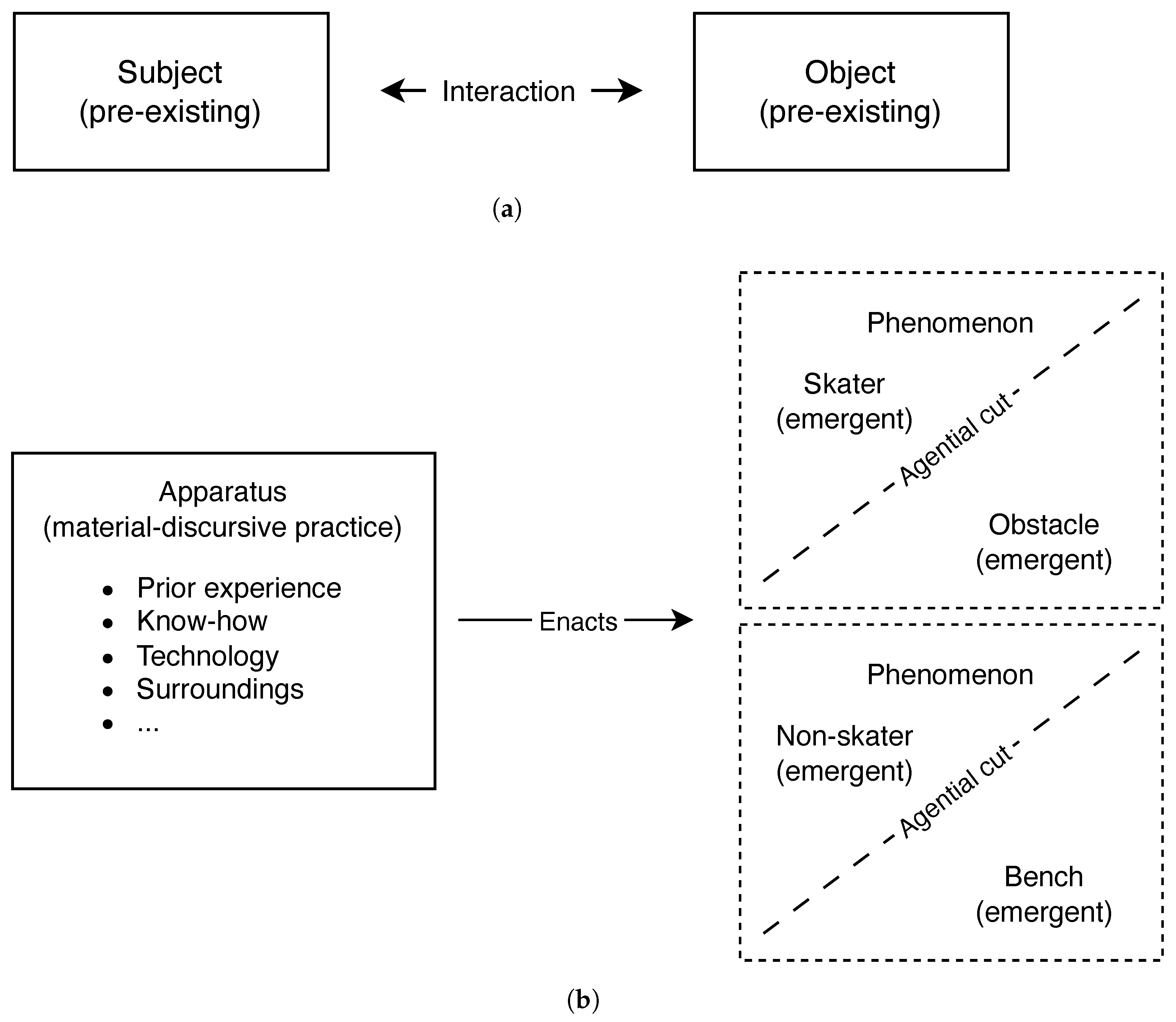

4.1. Agential Realism and Difference Making—How Interactions Are Enacted

What is recognised is not only an object but also the values attached to an object (values play a crucial role in the distributions undertaken by good sense). In so far as the practical finality of recognition lies in the ‘established values’, then on this model the whole image of thought as Cogitatio natura bears witness to a disturbing complacency.([20], p. 131)

Not a process of recollection, of the reproduction of what was, […] Rather, it is a matter of re-membering, of tracing entanglements, responding to yearnings for connection, materialized into fields of longing/belonging.([21], pp. 406–407)

4.2. From Designing Interaction to—Organizing Relational Complexity

Rather than thinking of a project as a design thing in terms of phases of analysis, design, construction and implementation, a participatory approach to this collective of humans and non-humans might rather look for the performative ‘staging’ of it.([31], p. 93)

Objectivity means being accountable for marks on bodies, that is, specific materializations in their differential mattering. We are responsible for the cuts that we help enact not because we do the choosing […], but because we are an agential part of the material becoming of the universe.([1], p. 178)

5. Conclusions

Further Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| NPO | Non-Profit Organization |

References

- Barad, K. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, K. Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2003, 28, 801–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, E.; van der Tuin, I. Diffraction & Reading Diffractively. 2016. Available online: https://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/d/diffraction.html (accessed on 12 March 2018).

- Norman, D.A. The Psychology of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Card, S.K. The Psychology of Human-Computer Interaction; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dix, A. Human-computer interaction. In Encyclopedia of Database Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1327–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.M. HCI Models, Theories, and Frameworks: Toward a Multidisciplinary Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- van Berkel, N.; Dennis, S.; Zyphur, M.; Li, J.; Heathcote, A.; Kostakos, V. Modeling Interaction as a Complex System. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 36, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephanidis, C.; Salvendy, G.; Antona, M.; Chen, J.Y.C.; Dong, J.H.; Duffy, V.G.; Fang, X.; Fidopiastis, C.; Fukuda, S.; Fu, L.; et al. Seven HCI Grand Challenges. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 1229–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, E. What is a complex system, after all? Found. Sci. 2024, 29, 1143–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladyman, J.; Lambert, J.; Wiesner, K. What Is a Complex System? Eur. J. Philos. Sci. 2013, 3, 33–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath-Carpentier, A. (Ed.) The Challenge of Complexity: Essays by Edgar Morin; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunenfeld, P. Design Research: Methods and Perspectives; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, I.M. Skateboarding, Space and the City: Architecture and the Body; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 1–318. [Google Scholar]

- Edén, G. (The City of Malmö, Malmö, Sweden). Personal communication, 30 September 2018.

- Arakawa, S.; Gins, M. Architectural Body; The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. Happy Objects. In The Affect Theory Reader; Gregg, M., Seigworth, G.J., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- de Petris, L.; Giger, P.; Carlsson, P. Affect and Intimacy in Generative Places. In Proceedings of the CITTA 8th Annual Conference on Planning Research/AESOP TG Public Spaces & Urban Cultures, Porto, Portugal, 24–25 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, K. Getting Real: Technoscientific Practices and the Materialization of Reality. Differ. J. Fem. Cult. Stud. 1998, 10, 87–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, G. Difference and Repetition; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, K. Transmaterialities: Trans*/matter/realities and queer political imaginings. GLQ J. Lesbian Gay Stud. 2015, 21, 387–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehner, K.; DePaula, R.; Dourish, P.; Sengers, P. Affect: From Information to Interaction. In Proceedings of the Fourth Decennial Conference on Critical Computing: Between Sense and Sensibility, New York, NY, USA, 20–24 August 2005; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Guribye, F.; Gjøsæter, T.; Bjartli, C. Designing for Tangible Affective Interaction. In Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Gothenburg, Sweden, 23–27 October 2016. NordiCHI ’16. [Google Scholar]

- Nansen, B.; van Ryn, L.; Vetere, F.; Robertson, T.; Brereton, M.; Dourish, P. An Internet of Social Things. In Proceedings of the 26th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on Designing Futures: The Future of Design, Sydney, Australia, 2–5 December 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sundström, P.; Ståhl, A.; Höök, K. In Situ Informants: Exploring an Emotional Mobile Messaging System in Their Everyday Practice. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, P. Visceral Design: Sites of Intra-action at the Interstices of Waves and Particles. In Proceedings of the Design, User Experience, and Usability: Novel User Experiences 2016, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–22 July 2016; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Frauenberger, C. Entanglement HCI: The Next Wave? ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. TOCHI 2019, 27, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draude, C. “Boundaries Do Not Sit Still” from Interaction to Agential Intra-action in HCI. In Proceedings of the Human-Computer Interaction. Design and User Experience: Thematic Area, HCI 2020, Held as Part of the 22nd International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hespanhol, L. Human-computer Intra-action: A Relational Approach to Digital Media and Technologies. Front. Comput. Sci. 2023, 5, 1083800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeinboeck, P. The Aesthetics of Encounter: A Relational-Performative Design Approach to Human-Robot Interaction. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 7, 577900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehn, P. Participation in Design Things. In Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design, Bloomington, Indiana, 1–4 October 2008; pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Weibel, P.; Latour, B. Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, T.; De Michelis, G.; Ehn, P.; Jacucci, G.; Linde, P. Design Things; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stroock, D.W. An Introduction to Markov Processes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 230. [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich, A. Searching for Non-Causal Explanations in a Sea of Causes. In Explanation Beyond Causation: Philosophical Perspectives on Non-Causal Explanations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeler, Ä.; Wolf, S. Non-causal computation. Entropy 2017, 19, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Petris, L.; Gullbrandson, F.; Falk, A.; Zhou, Y.; Khatibi, S. Agential RealistAnticipation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Gaming, Entertainment and Media (GEM 2025), Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 16–18 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; de Petris, L.; Khatibi, S. Towards Human-Like Behavior Generation by Appling Markov Chain Monte Carlo in realization of Agential Realism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Computer, Data Sciences and Applications (ACDSA 2025), Antalya, Türkiye, 7–9 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Feature | Interaction | Intra-Action |

|---|---|---|

| Ontological primacy | Objects are primary | Relations are primary |

| Boundaries | Pre-existing and static | Emergent and dynamic |

| Entities | Independent | Inseparable “relata” |

| The “action” | Occurs between entities | Process that constitutes the entities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Petris, L.; Khatibi, S. Organizing Relational Complexity—Design of Interactive Complex Systems. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9080081

de Petris L, Khatibi S. Organizing Relational Complexity—Design of Interactive Complex Systems. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2025; 9(8):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9080081

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Petris, Linus, and Siamak Khatibi. 2025. "Organizing Relational Complexity—Design of Interactive Complex Systems" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 9, no. 8: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9080081

APA Stylede Petris, L., & Khatibi, S. (2025). Organizing Relational Complexity—Design of Interactive Complex Systems. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 9(8), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9080081