Dating apps have become essential to contemporary social interactions, especially within the LGBTIQA+ community, providing platforms for connection and companionship. However, growing concerns surround their potential impact on users’ mental health, as issues such as cyberbullying, fear, anxiety, and stress emerge as key psychological challenges. Additionally, examining factors like mood, pleasure, self-confidence, and security can offer deeper insights into the complex dynamics between dating app usage and mental health outcomes. This study seeks to illuminate ways to promote user well-being, with a particular focus on the experiences of LGBTIQA+ individuals.

3.2. Hypotheses

Goette et al. [

21] found that stress significantly affects self-confidence, with individuals experiencing high levels of anxiety showing a marked decrease in self-confidence under stress compared to those with lower anxiety levels. Notably, in their study, they used a median split of trait anxiety scores, categorizing participants into high-anxiety (

= 55) and low-anxiety (

= 54) groups. These findings imply a connection between anxiety levels and self-confidence indicating that individuals with heightened anxiety may exhibit lower self-confidence, compared to those with lower anxiety levels. Additionally, Chorney and Morris [

22] emphasized that individuals with elevated dating anxiety seek validation and demonstrate increased shyness in social situations. This suggests that users who are anxious about dating might use dating apps to feel good about themselves and talk to others more easily, compared to people who are not as nervous. In that respect, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1. Anxiety is negatively associated with self-confidence among LGBTIQA+ individuals using online dating apps.

Lutz and Ranzini [

23] highlight that users of dating apps, such as Tinder, express significant concern over how companies manage their personal data, fearing misuse more than exposure to other users. This concern underscores a strong anxiety regarding the security of their information within the dating app. Complementing this, research by Farndenet et al. [

24] highlights the technical vulnerabilities within dating apps, such as Grindr, that exacerbate privacy risks by sharing detailed user information, including unencrypted profile pictures and precise location data. This not only increases anxiety among users but also poses a distinct risk to marginalized communities, including LGBTIQA+ individuals, who may rely on these platforms for social connections while requiring a higher degree of anonymity for safety. Manning and Stern [

25] further emphasize this point, noting that the spreading of personal data can particularly endanger those who depend on digital anonymity for their well-being. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2. Anxiety is negatively associated with perceived security in online dating apps used by LGBTIQA+ individuals.

Sumter and Vandenbosch [

26] found that individuals experiencing high levels of dating anxiety are less inclined to engage with dating platforms, a behavior consistent with avoidance patterns observed among young adults faced with dating-related distress. This aligns with broader findings regarding technology apprehension. Rosen et al. [

27] identified a specific factor in their study indicating a negative attitude toward technology, characterized by perceptions of it as time-wasting, socially isolating, and overly complex. These attitudes were inversely related to technology anxiety and dependence, suggesting that higher anxiety correlates with more negative views on technology use. Further supporting this notion, Korobili et al. [

28] found a significant negative relationship between anxiety and attitudes toward technology among undergraduates, reinforcing the notion that anxiety—especially related to dating and technology—contributes to negative perceptions of dating apps. Collectively, these studies underscore the complex connection between anxiety and attitudes towards dating apps. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3. Anxiety is negatively associated with attitude toward online dating apps among LGBTIQA+ users.

Dredge et al. [

29] underscore the significant impact of cyberbullying on victims, linking it to severe outcomes including depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. This finding is corroborated by Carvalho et al. [

30], who report that cyberbullying victims frequently suffer from a range of psychological issues, such as anxiety, depression, PTSD, and suicidal thoughts, indicating a profound effect on mental health. Moreover, Huang et al. [

31] revealed a direct correlation between adolescent engagement with online dating platforms, experiences of online victimization, and negative psychological impacts, including anxiety. Schenk [

32] further highlights the serious psychological consequences of cyberbullying, noting an increased prevalence of mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, and emotional distress among victims. Similarly, Kokkinos et al. [

33] found that adolescents facing online harassment are at a greater risk of developing mental health problems, including anxiety and depression. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4. Cyberbullying is positively associated with anxiety related to online dating app use in the LGBTIQA+ population.

Corriero and Tong [

34] claim that socially anxious users are concerned about their profiles being recognized by family and acquaintances, highlighting their fears about losing privacy and security. This fear is rooted in social anxiety tendencies, where individuals fear judgment and seek reassurance, as discussed by Cougle et al. [

35], who link excessive reassurance seeking with social anxiety. Furthermore, Venkatesh and Davis [

36] broaden the scope of this anxiety to technological interactions, positing that anxiety refers to fear over data loss or errors when utilizing technology. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5. Fear is positively associated with anxiety in online dating app interactions among LGBTIQA+ users.

A meta-analysis conducted by Tannenbaum et al. [

37] revealed that fear appeals were successful at influencing attitudes, intentions, and behaviors across nearly all conditions that were analyzed, including cigarette smoking, breast self-examination, sunscreen usage, and medication adherence. Higher levels of fear generate systematic processing, which, in turn, leads to greater persuasion [

38,

39,

40]. However, in the context of online dating within the LGBTIQA+ community, fear is primarily associated with concerns about privacy breaches, discrimination, and potential harm, which are well-documented barriers to engagement with digital platforms. Prior research has shown that heightened fear related to digital risks often leads to avoidance behaviors rather than increased adoption [

41,

42]. Given these factors, we hypothesize the following:

H6. Fear is negatively associated with attitude toward online dating apps within the LGBTIQA+ community.

Blomfield Neira and Barber [

41] discuss how frequently social media usage can inversely affect self-esteem and mood, suggesting that an increase in the use of these platforms can lead to higher instances of depressed moods and poorer self-perceptions. Forgas [

42] explores how mood influences the processing of self-confidence information, revealing that positive moods enhance the primacy effect, which elevates perceived self-confidence when positive traits are introduced first. Conversely, negative moods diminish this advantage and lead to a recency effect, where later information has a stronger influence on impression formation. This mutual relationship suggests that self-confidence can alleviate negative moods, but mood can also influence how self-confidence is perceived and formed. In that respect, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7. Self-confidence is positively associated with mood while using online dating apps among LGBTIQA+ individuals.

Chu et al. [

43] found a significant correlation between cyberbullying victimization and adolescents’ psychosocial problems, highlighting how the experience of being bullied online can contribute to lower self-worth and social difficulties. This assertion is further confirmed by Baruah et al. [

44], whose study revealed that a substantial majority of respondents involved in cyberbullying reported low levels of self-esteem. Conversely, only a small fraction reported medium levels of self-esteem, suggesting a strong association between cyberbullying involvement and decreased self-esteem among adolescents. Additionally, Tsaousis [

45] indicates that lower levels of self-esteem are linked to higher risks of both bullying perpetration and victimization, reinforcing the notion that cyberbullying can detrimentally impact individuals’ self-confidence and overall psychological well-being. These findings collectively emphasize the harmful impact of cyberbullying on users’ self-perception and highlight the pressing need for interventions to alleviate the negative consequences of online harassment, particularly in digital environments such as dating apps. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H8. Cyberbullying is negatively associated with self-confidence in LGBTIQA+ individuals using online dating apps.

Phan et al. [

46] highlight the physiological and psychological effects that users may experience due to potential crimes such as stalking, fraud, and sexual abuse, which can lead to emotional distress and injury to self-esteem. Additionally, findings from a qualitative study by Cobb et al. [

47] indicate that while some users express confidence in their ability to prevent security issues by being cautious with the information they share online, others feel vulnerable and anxious about potential security breaches. Participants who lack security concerns often attribute their confidence to having nothing to hide or feeling that their profiles contain relatively innocuous information. However, even seemingly basic personal details—such as age, ethnicity, or sexual position preferences—can pose risks if exploited maliciously, particularly within the LGBTIQA+ community, where such data may be used for doxxing, outing, targeted harassment, or discrimination. Prior research has documented cases where dating app data have been leveraged in blackmail schemes, social engineering attacks, and even police surveillance in regions where non-heteronormative identities are criminalized [

48,

49]. While some users mitigate these risks by providing false information, this practice is neither universal nor entirely protective, as behavioral patterns and metadata can still be used to infer sensitive attributes. This underscores the complex interplay between security considerations and users’ self-confidence in online dating environments. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H9. Security is positively associated with self-confidence in online dating apps for LGBTIQA+ users.

Breitschuh and Göretz [

50] discovered that the fear of potential misuse of profile or chat data was one of the primary reasons users provide false information on dating apps, highlighting their anxiety regarding the security of their personal information. While the use of false information may serve as a protective strategy, it does not entirely mitigate the risks associated with online exposure. Users may still experience fear due to the possibility that their real identities could be uncovered through cross-referencing data, social engineering tactics, or platform vulnerabilities. Additionally, cyberstalking is characterized by intrusive and repetitive digital practices aimed at dominating victims’ intimate lives, with which they breach victims’ security. Even when users attempt to obscure their identity by providing misleading details, persistent cyberstalkers may exploit metadata, behavioral patterns, or linked accounts to circumvent these defensive measures. This contributes to heightened feelings of fear and vulnerability among users [

51]. This form of harassment, which includes surveillance, threats, and identity theft, increases anxiety about online security. While some users may perceive that falsifying certain profile elements offers a degree of protection, the broader risk of being targeted remains, particularly when perpetrators engage in sustained digital tracking or manipulation. As a result, even individuals who employ deception as a safeguard may still experience fear regarding their safety and security on dating platforms. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H10. Fear is negatively associated with perceived security in online dating apps among LGBTIQA+ individuals.

Privacy awareness plays a significant role in shaping how individuals feel about and perceive mobile apps. This influence extends to users’ attitudes towards these platforms, as highlighted by Li et al. [

52]. Furthermore, awareness of threats and privacy concerns in the information technology environment significantly impacts users’ attitudes and intentions regarding the use of mobile apps and the sharing of personal information [

53]. For instance, a study by Wottrich et al. [

54] found that perceived privacy concerns negatively influenced users’ attitudes and decisions to use and grant app permission requests for accessing personal information. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H11. Security is negatively associated with attitude toward online dating apps in the LGBTIQA+ population.

Consequences of cyberbullying often include significant psychological distress, with victims experiencing fear, discomfort, threat, anger, and sadness [

55]. Despite the presence of online romantic interactions, adolescents and young adults exhibit a pervasive apprehension of dating violence and cyber abuse, yet they continue to use online platforms for dating and flirting, even amidst fears of violence and deception [

56]. Studies have indicated that cyber-victimized individuals, particularly young women and those targeted by former partners, report heightened levels of fear, while men increasingly report fear when cyberstalking involves previous close relationships [

57]. Threats and intimidation, common forms of cyberbullying, generate intense fear in victims, contributing to concerns about personal safety and well-being [

58]. The nature of cyber-humiliation, which can occur through various online platforms at any time, exacerbates feelings of fear and the sense of being constantly monitored or tracked [

59]. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H12. Cyberbullying is positively associated with fear related to online dating app use in the LGBTIQA+ community.

Holtzhausen et al. [

60] observed significantly higher levels of psychological distress and depression among dating app users, suggesting a correlation between dating app use and negative mood outcomes. Moreover, recent research indicates that stress can dysregulate dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, potentially exacerbating mood disorders [

61]. Dysregulation of the stress system has been documented in mood disorders, further highlighting the relationship between stress and negative mood states. Additionally, Kassel et al. [

62] emphasize that stress often leads to negative mood states, which individuals typically find aversive. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H13. Stress is negatively associated with mood while using online dating apps among LGBTIQA+ individuals.

Bonilla-Zorita et al. [

63] found that better mood and self-esteem were associated with receiving notifications on dating apps, implying a positive correlation between app interactions and emotional well-being. Furthermore, pleasure, a crucial component of happiness, shares neural mechanisms with other pleasurable experiences such as socializing with friends [

64]. Given these considerations, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H14. Mood is positively associated with pleasure in online dating app interactions in the LGBTIQA+ population.

Castañeda et al. [

65] demonstrated a positive relationship between users’ positive experiences and their attitude toward technology, suggesting that enjoyable experiences contribute to favorable attitudes. Additionally, Luo [

66] found that individuals perceiving the web as entertaining and informative tend to have a positive attitude towards it, supporting the notion that pleasure influences attitude. Furthermore, Finkel et al. [

67] noted that greater experience with online dating can lead to more positive attitudes, emphasizing the role of user experience in shaping attitudes towards dating platforms. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H15. Pleasure is positively associated with attitude toward online dating apps among LGBTIQA+ users.

Dwivedi et al. [

68] highlighted a direct path from users’ attitudes to usage behavior, indicating that individuals with a positive attitude are more inclined to use information systems or technology. Bryant and Sheldon [

69] also emphasized the significance of attitudes in determining the use of cyber dating apps, aligning with the theory of reasoned action. Additionally, Huang [

70] found that subjective well-being strongly influences users’ intention to continue using technology. In that respect, we propose the following hypothesis:

H16. Attitude is positively associated with behavioral intention to use online dating apps among LGBTIQA+ individuals.

The conceptual model illustrating the interrelationships among the constructs in the form of hypotheses is presented in

Figure 1. The proposed model was designed to capture the most theoretically and empirically relevant relationships within the context of LGBTIQA+ individuals using online dating apps. Certain linkages, such as the relationship between stress and anxiety, were not tested due to the study’s focus on more immediate predictors of self-confidence, security, and attitude. Prior research suggests that stress can directly contribute to anxiety in digital environments, particularly when triggered by cyberbullying. For instance, studies have shown that victims of cyberbullying report increased stress, which can lead to anxiety and depressive symptoms [

71,

72]. To maintain conceptual clarity and prevent overparameterization, only the most central pathways were included. This approach aligns with best practices in structural equation modeling, where parsimony is favored to enhance interpretability and reduce the risk of overfitting [

73].

3.3. Procedure and Apparatus

For the purpose of data collection, a new questionnaire was developed. The constructs measured in the study were identified as a result of the literature review presented in

Section 2. Although the target population consisted of individuals living in countries where the languages spoken are relatively similar, the survey instrument was formulated in English to ensure conceptual consistency and broader applicability of the findings.

The data were collected using an online survey via Google Forms from 17 July 2023 to 27 March 2024, targeting current LGBTIQA+ users of dating apps as respondents. Participants were primarily from Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia. We efficiently collected responses by distributing the questionnaire to LGBTIQA+ Discord channels and popular regional online communities serving these populations. We also engaged with several Facebook groups dedicated to sharing surveys and receiving responses to gather additional data. Furthermore, we received support from acquaintances and personally invited participants through face-to-face interactions.

The questionnaire comprised 5 items related to participants’ demography (age, sex, gender, sexuality, current country of residence); two items were designed to collect data on the time respondents spend on dating apps, along with five multiple-response items intended to gather information on the reasons for the app usage; one item for the names of frequently used apps; and four items aimed at understanding participants’ experiences and communications with other users, as well as their offline interactions with individuals they have met on dating apps.

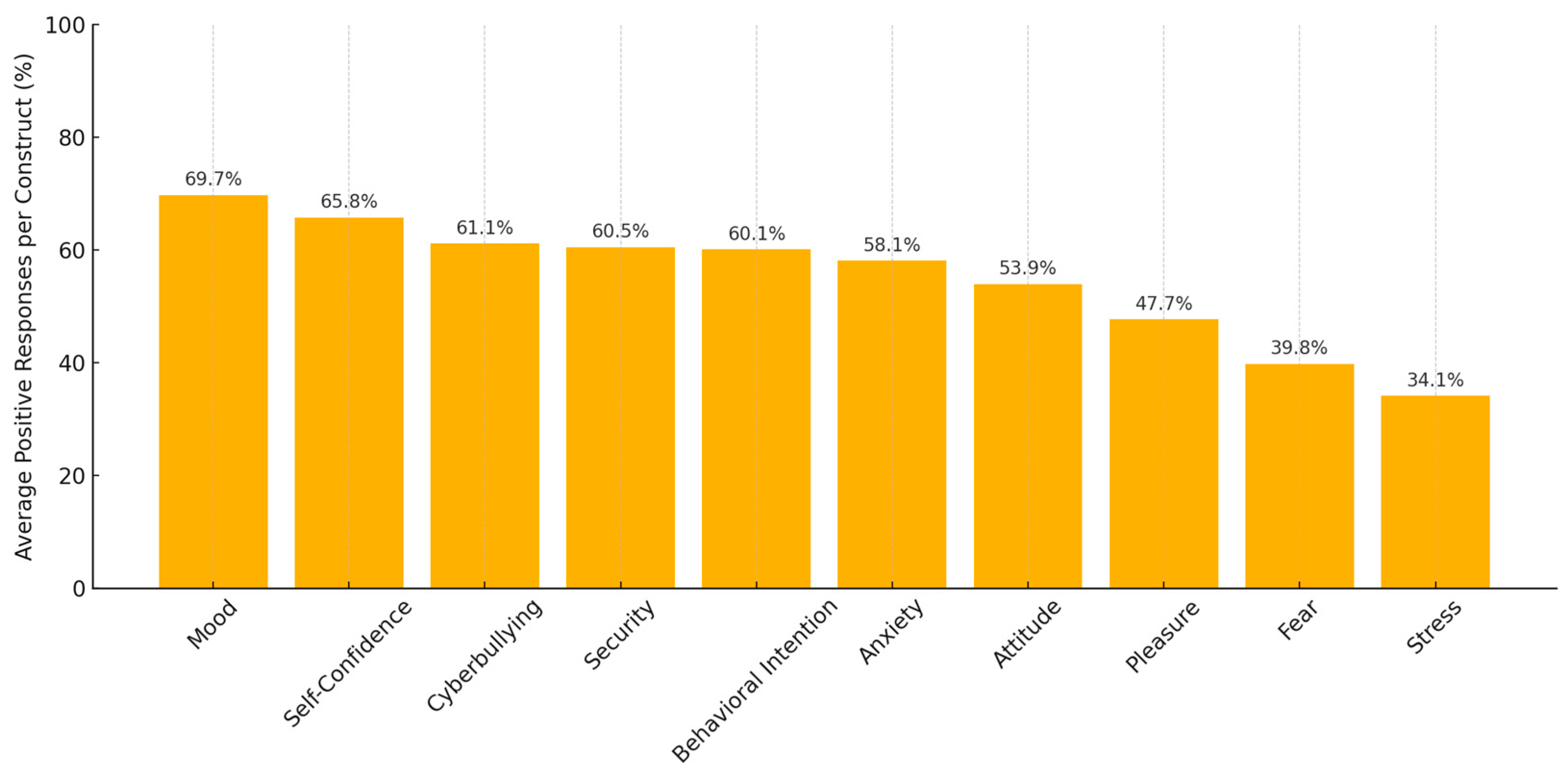

The dimensions of the constructs comprising the proposed research model were measured using between 5 and 10 items: self-confidence (10 items), security (5 items), anxiety (8 items), mood (6 items), stress (6 items), fear (9 items), cyberbullying (6 items), attitude (8 items), pleasure (5 items), and behavioral intention (5 items). The items were worded by the first and second authors of the study to ensure alignment with the conceptual definitions of each construct. Responses to questionnaire items were modulated on a five-point Likert scale (1—strongly disagree, 5—strongly agree).

A statistical approach known as partial least squares structural equation modeling was applied to assess the reliability and validity of the research model and to examine the proposed relationships. Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a method for analyzing multivariate data, particularly for theory testing [

74]. Partial least squares SEM (PLS-SEM) is a causal modeling technique focusing on maximizing the explained variance of dependent latent constructs rather than constructing a theoretical covariance matrix [

75]. It is advantageous for exploratory research, handling complex models with small to medium sample sizes, and emphasizing prediction without imposing high data demands or requiring specified relationships [

76,

77]. PLS-SEM is especially useful when the research objective is predictive, making it popular in field of human–computer interaction. Researchers can model latent variables through their indicators and assess relationships even with measurement error. Using the inverse square root method proposed by Kock and Hadaya [

78] and considering effect size ranges required for achieving 80% statistical power with the minimum path coefficient expected to be significant at the 5% level [

73], our minimum required sample size was determined to be 138. With an actual sample size of 204, our study is considered statistically robust. The SmartPLS 4.1.0.0 software tool [

79] was used to evaluate the psychometric properties of both the measurement and structural models. SmartPLS was chosen over other commercial PLS-SEM applications (such as WarpPLS and ADANCO) due to its robust analytical capabilities, intuitive interface, and comprehensive support resources, which together enabled rigorous analysis and modeling of complex relationships in this study.