Multisensory Technologies for Inclusive Exhibition Spaces: Disability Access Meets Artistic and Curatorial Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Historical Background of Disability Activism in the Cultural Field

2.1. Technologies for Sensory Accessibility in Exhibitions

2.2. Points of Critique

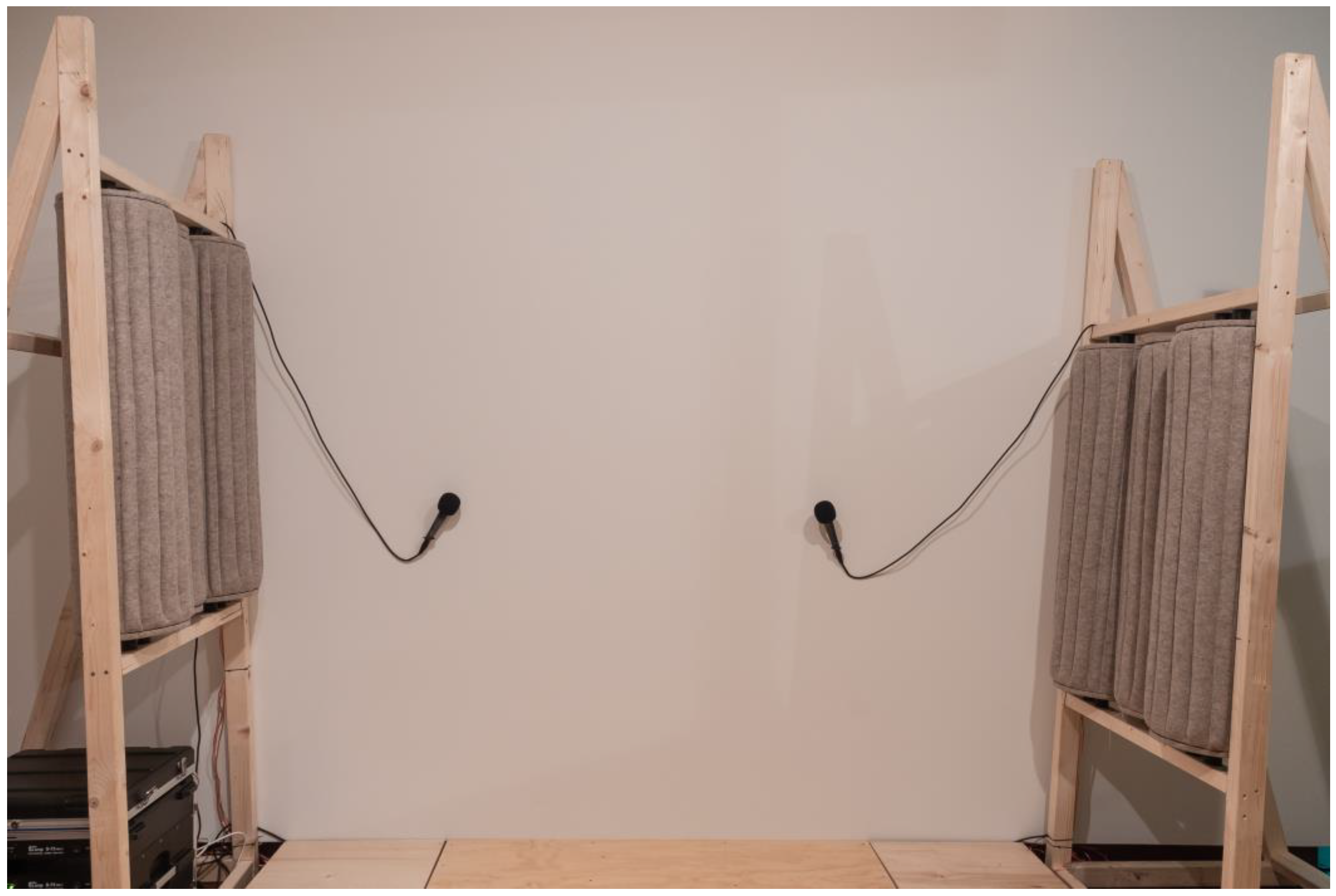

2.3. Case Study: Artistic and Curatorial Experimentation with Haptic Architecture

- Aim 1: To explore how various types of sound input ‘translated’ into vibrations were received by testers with diverse hearing abilities and diverse levels of familiarity with vibrotactile experiences in art and music.

- Aim 2: To test the reception of the prototypes as tools in the conditions of a formal exhibition space, a white cube.

3. Results and Conclusions

4. Discussion–Theoretical Reflections

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- User [x]

- I.

- Floor tile

- Reminds me of being at a concert, feeling sound inside me, when the ‘clocks’ sound is on.

- II.

- Porcelain tiles

- So far the most subtle object. I find them pretty cold when I lean against them.

- I cannot always connect what I feel to what I hear. It’s nice that now I found out that I can move them and press on them with my body.

- III.

- Piping

- It’s comforting. Nice to lean on something, makes me feel safe.

- IV.

- Tactile Wall

- Very intense. I am confused about what I feel and what I hear, where the sound comes from. I like the bouncing.

- I can still feel it in my chest after a while.

- Funny, by the way, that I‘m confused, whereas this is the part I can control.

- V.

- Feathers

- I find it’s funny, but I can hear my own voice very well so it adds less of a new layer. The feathers are cute, and I experimented with different effects of different sounds. More playful, like a game.

- I.

- Floor tile

- When I was lying on the floor for the first time I had actually heard the music not [only] felt it. It is very subtle and if there are a lot of sounds of people talking in the room these sounds generally disappear into the ambient/environment ... [illegible word]-I find that a bit unfortunate.

- II.

- Porcelain tiles

- I felt these very nice, especially because they touch different parts of the body. I went against it with my back but also the other way around. It is very intimate and brings you close to yourself because you can feel it in your body.

- III.

- Piping

- This one also felt like a kind of fine massage, also because you can sit resting against it. And there were differences in the strength [sic] (vehemence) which I found interesting

- IV.

- Tactile Wall

- This was really fun because it was interactive, like a video game. liked the playful element! I felt it very clearly!

- V.

- Feathers

- The feathers seem kind of sensible critters. Really special to see the movements [of the] feathers. I was wondering if the feathers respond to the ambient sounds or some other internal vibration.

- I.

- Floor tile.

- The vibrating plates feel for me better than the previous time. I know that the sound is a lion growl.

- A pillow would make it a complete set. Then my body can perceive the vibrations. From the head to the feet.

- II.

- Porcelain tiles

- There are different sounds in these prototypes. Also very interesting to see and to experience. What I think is genius, is the 3D shaped [… two illegible words …] that move along.

- Sometimes it’s hard to judge a sound/situation. Using a sign [i.e., something to look at, translator’s note] will make it easier for visitors.

- Example: birds in the woods.

- III.

- Piping

- To be honest, I feel less strong vibrations than last time. As a result, I can’t properly imagine the location of a sound as a vibration takes place.

- One hard vibration I felt was at the location of my buttocks and feet.

- IV.

- Tactile Wall

- First of all, I didn’t feel well which side was vibrating. It felt to me [like] general vibration. It took some getting used to (a little too hard).

- Secondly, I took off my belt and blindfolded, I pretended to be deafblind.

- This (sic) attempt turned out to be better than I expected: deeper feeling in a vibration. I could visualize better in a dance movement, play a joystick.

- Tip: add a blindfold (or sound- ...??), then the visitors can blindfold and use it. they can understand better.

- And the vibrations may sound little softer without [I think this should be: ‘to avoid’] scaring visitors.

- V.

- Feathers

- I have noticed that feathers ‘vibrate’ due to the sound wave. The more intense the wave is, the harder a feather vibrates.

- ○

- The sound wave translates into feathers.

- ○

- I also love to see how the feathers react.

- ○

- Tip: The cushion is too low for me to be able to feel everything I see. Better to put it up to the top of our body.

References

- Oliver, M. The social model in action: If I had a hammer. In Implementing the Social Model of Disability: Theory and Research; Mercer, C.B.A.G., Ed.; The Disability Press: Leeds, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bismarck, B.V. The Curatorial Condition; Sternberg Press: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikx, B. (Ed.) Queer Exhibition Histories; Valiz: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Linsey, Y. (Ed.) Women in Revolt!: Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990; Tate Britain: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cachia, A. Curating Access: Disability Art Activism and Creative Accommodation; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garland-Thomson, R. (Ed.) Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Garland-Thomson, R. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature, 2nd ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. first published 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty, B. Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, expanded ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Staniszewski, M.-A. The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art; MIT Press & MoMA: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, P. Exhibition Design; Laurence King Publishing: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Candlin, F. Art, Museums and Touch; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clintberg, M. Where Publics May Touch. Senses Soc. 2014, 9, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, C. (Ed.) The Book of Touch; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Classen, C. The Museum of the Senses: Experiencing Art and Collections; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pursey, T.; Lomas, D. Tate Sensorium: An experiment in multisensory immersive design. Senses Soc. 2018, 13, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, C.; Leemans, I.; Fleming, B. How can scents enhance the impact of guided museum tours? towards an impact approach for olfactory museology. Senses Soc. 2022, 17, 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeds, L. (Ed.) Exhibition; The MIT Press & Whitechapel Gallery: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Justice, J. Disabled Artists, Audience, and the Museum as the Place of Those Who Have No Part’. In Curating Access; Cachia, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Molley, S. Highlighting Disabled Experience through an Interdisciplinary and Socially Engaged Art Project. In Curating Access; Cachia, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guffey, E.; Williamson, B. Introduction: Rethinking design history through disability, Rethinking disability through design. In Making Disability Public; Bloomsberry: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fondation de France; ICOM. Museums without Barriers: A New Deal for Disabled People; ICOM: Paris, France; Routledge: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Art Beyond Sight. Bringing Art Culture to All. Available online: https://artbeyondsight.wordpress.com (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Axel, E.S.; Levent, N.S. Art Beyond Sight: A Resource Guide to Art, Creativity, and Visual; Amer Foundation for the Blind: Arlington, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- In Gebaren. Musea in Gebaren. Available online: https://ingebaren.nl/doe-mee-in-gebaren/musea-in-gebaren/ (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Bahram, S. The inclusive museum. In The Senses: Design Beyond Vision; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz, R.; Freitas, D.; Coelho, A. Blind and Visually Impaired Visitors’ Experiences in Museums: Increasing Accessibility through Assistive Technologies. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2020, 13, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dover, C.; Jeffereis, M. Educators from the Guggenheim, the Met, and MoMA Discuss Access at Museums. 22 July. 2015. Available online: https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/checklist/educators-from-the-guggenheim-the-met-and-moma-discuss-access-at-museums (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Butler, J. Writing the Central Role of Captions in Live Performances. Coll. Engl. 2023, 85, 498–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, K. The Sound Shirt Lets Deaf People Feel Music on Their Skin. 4 October. 2019. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/technology/cute-circuit-deaf-people-feel-music-skin-soundshirt-haptic-sensors-10-04-2019/ (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Hughes, A. BBC Science Focus. 2 October. 2023. Available online: https://www.sciencefocus.com/future-technology/these-vibrating-vests-bring-music-to-life-for-deaf-gig-goers (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Karam, M.; Branje, C.; Nespoli, G.; Thompson, N.; Russo, F.A.; Fels, D.I. The Emoti-Chair: An Interactive Tactile Exhibit. In Proceedings of the CHI EA ‘10: CHI ‘10 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- VibraFusionLab. VibraFusionLab Current Projects. Available online: https://www.vflvibrafusionlab.com/current-projects.html (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Zavitsanos, C. Constantina Zavitsanos. Info. Otherpeoplespixels. Available online: https://constantinazavitsanos.com/news.html (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- D’Evie, F. From dust to dust. Hallucinating the absent exhibition. In Curating Access; Cachia, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 87–98, Kindle edition. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, A. Ann Cunningham. Available online: https://acunningham.com/ (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Moser, I. The promise of technology. In Disability, Space, Architecture; Boys, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Cryle, P.; Stephens, E. Normality: A Critical Genealogy; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, C. Measuring Difference, Numbering Normal: Setting the Standards for Disability in the Interwar Period; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kafer, A. Feminist, Queer, Crip; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare, T. The Social Model of Disability. In The Disability Studies Reader; Davis, L.J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 266–273. [Google Scholar]

- The Other Abilities. Available online: https://otherabilities.org/ (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Bourachot, A.; Bouchara, T.; Cornet, O. Impact of an audio-haptic strap to augment immersion in VR video gaming: A pilot study. In Proceedings of the 18th International Audio Mostly Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 30 August 2023–1 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bobier, D.; Sawchuk, K.; Thulin, S. An Interview with David Bobier of VibraFusionLab. Can. J. Disabil. Stud. 2021, 10, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadi, E.; What Do I Hear? Project Team. Collective improvisation for accessible exhibition spaces. In Proceedings of the Design as Collective Improvisation, Brussels, Belgium, 4–6 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, F.C.; Rosenberg, F. Art Making as Multisensory Engagement. In The Multisensory Museum; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fotiadi, S.E. Multisensory Technologies for Inclusive Exhibition Spaces: Disability Access Meets Artistic and Curatorial Research. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2024, 8, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti8080074

Fotiadi SE. Multisensory Technologies for Inclusive Exhibition Spaces: Disability Access Meets Artistic and Curatorial Research. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2024; 8(8):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti8080074

Chicago/Turabian StyleFotiadi, Sevasti Eva. 2024. "Multisensory Technologies for Inclusive Exhibition Spaces: Disability Access Meets Artistic and Curatorial Research" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 8, no. 8: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti8080074

APA StyleFotiadi, S. E. (2024). Multisensory Technologies for Inclusive Exhibition Spaces: Disability Access Meets Artistic and Curatorial Research. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 8(8), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti8080074