Towards Explainable and Sustainable Wow Experiences with Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Which psychological and technical factors contribute to a wow experience?

- How can wow experiences be measured?

2. Materials and Methods

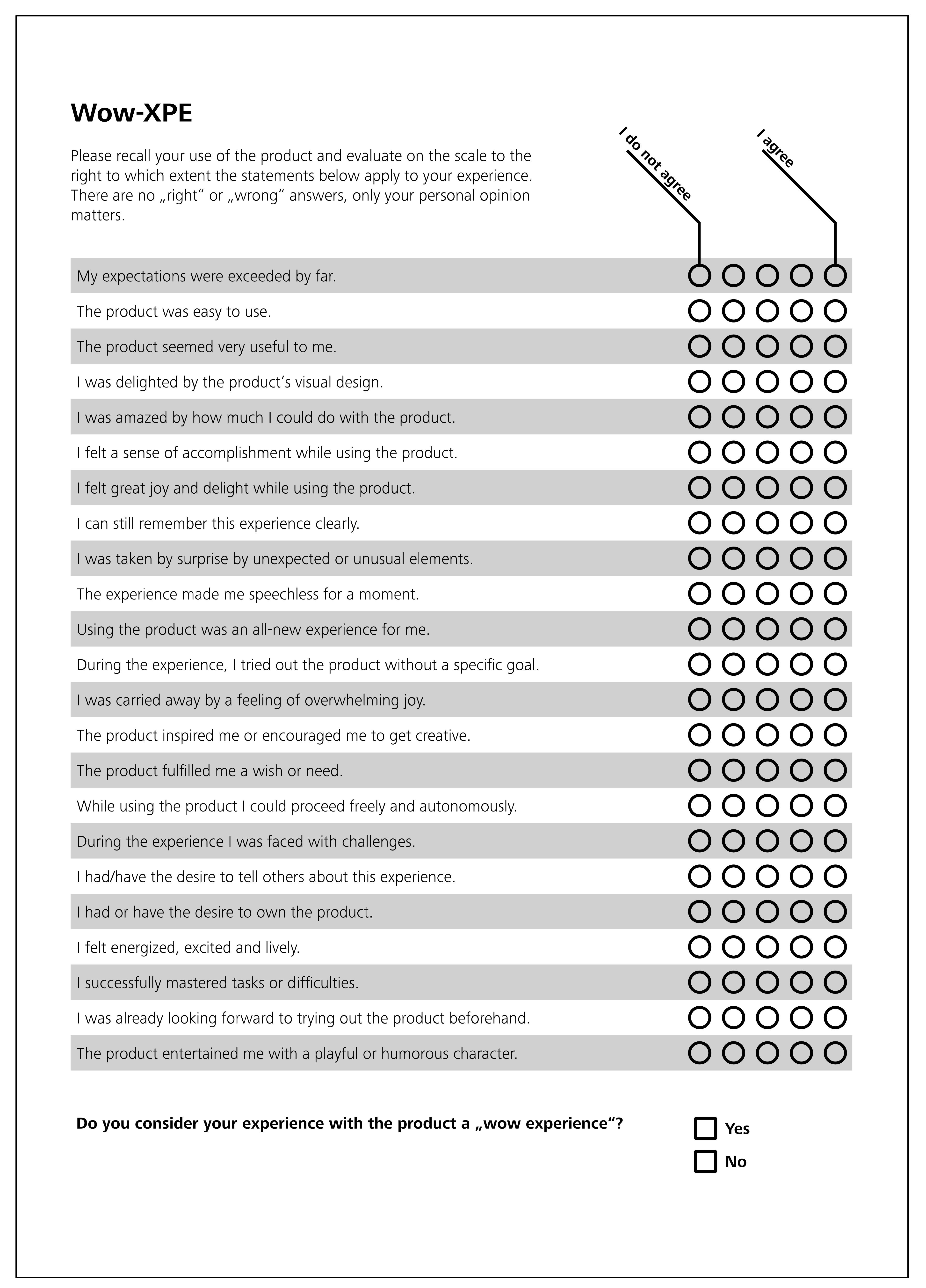

2.1. Item Development

2.2. Survey

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Wow Experiences

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.3. Wow Factors

3.4. Comparison of Wow Experiencees with Different Technologies

4. Discussion

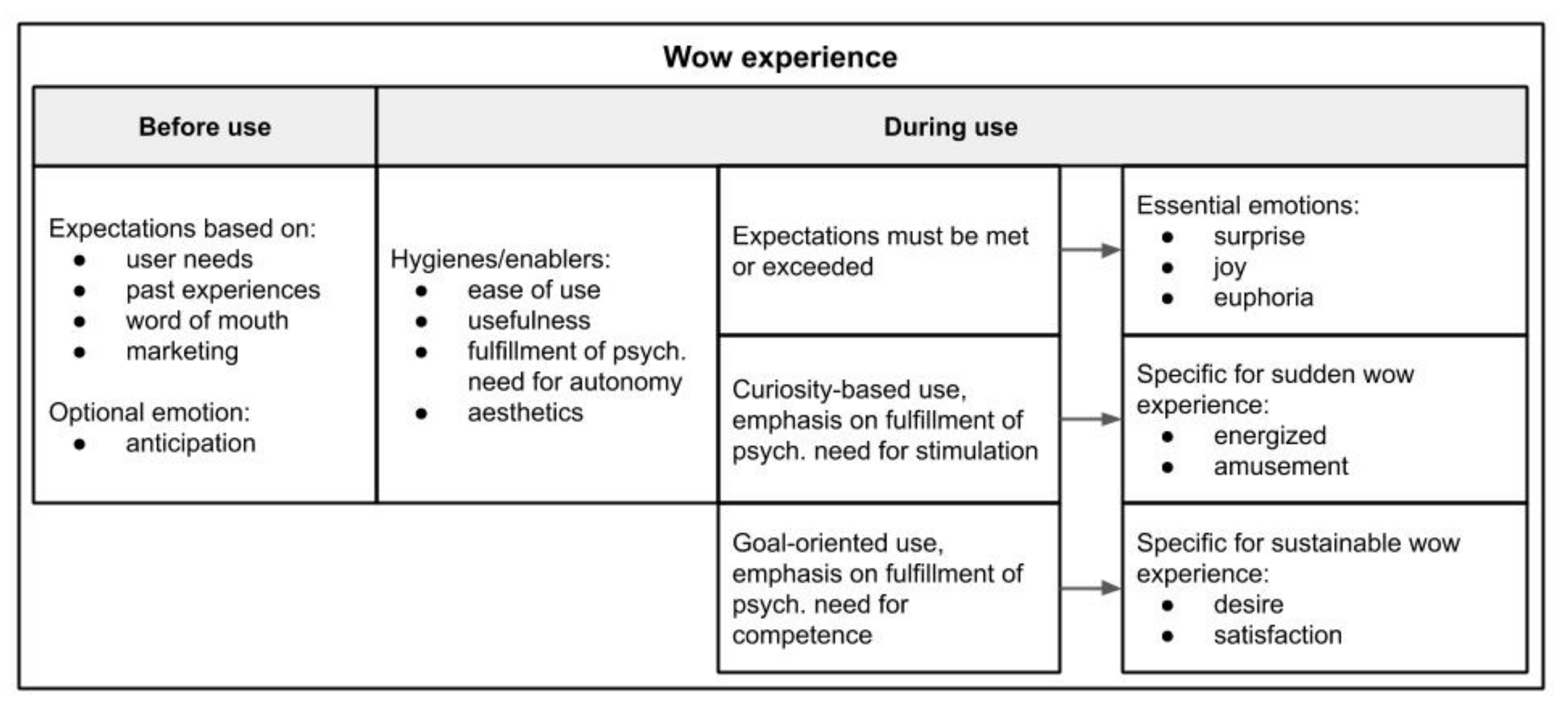

4.1. General Discussion

4.2. Integrated Model of Wow Experience

4.3. Wow-XPE Questionnaire

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Hudson, J.M.; Viswanadha, K. Can “wow” be a design goal? Interact 2009, 16, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, M.; De Koning, N.; Hoyng, L. The “wow: Experience—Conceptual model and tools for creating and measuring the emotional added value of ICT. In Proceedings of the COST269 Conference, Helsinki, Finland, 3–5 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, M. User Experience (UX): Towards an Experiential Perspective on Product Quality. In Proceedings of the 20th international conference on Association Francophone d’Interaction Homme-Machine, Metz, France, 2–5 September 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Porcelijn, R.; van Dijk, M.B. How to design wow? Introducing a layered- emotional approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 24–27 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N. The Emotions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ortony, A.; Clore, G.L.; Collins, A. The Cognitive Structure of Emotions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K.; Palviainen, J.; Pakarinen, S.; Lagerstam, E.; Kangas, E. User perceptions of Wow experiences and design implications for Cloud services. In Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces (DPPI ’11), Milano, Italy, 22–25 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pieskä, S.; Qvist, P.; Tuusvuori, O.; Suominen, T.; Luimula, M.; Kaartinen, H. Multidisciplinary Wow experiences boosting SMEi. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications, Wrocław, Poland, 16–18 October 2016; pp. 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reunanen, T.; Penttinen, M.; Borgmeier, A. “Wow factors” for boosting business. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Proceedings of the AHFE 2016 International Conference on Human Factors, Business Management and Society, Walt Disney World®, FL, USA, 27–31 July 2016; Kantola, J.I., Barath, T., Nazir, S., Andre, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulzer, M.; Burmester, M. Outstanding UX-Eine systematische Untersuchung von Wow-Effekten (Outstanding UX-A Systematic Investigation of Wow Experiences). In Proceedings of the Mensch und Computer 2018 (MUC ‘18), Dresden, Germany, 2–5 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Diefenbach, S.; Göritz, A. Needs, affect, and interactive products-Facets of user experience. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Wiklund-Engblom, A.; Bengs, A.; Hägglund, S.; Diefenbach, S. Experience-oriented and product-oriented evaluation: Psychological need fulfillment, positive affect, and product perception. Int. J. Hum-Comput. Interact. 2015, 31, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuch, A.N.; van Schaik, P.; Hornbæk, K. Leisure and work, good and bad: The role of activity domain and valence in modeling user experience. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. (TOCHI) 2016, 23, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J.; Kim, Y.; Kasser, T. What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmet, P.M.A. Faces of product pleasure: 25 positive emotions in human-product interactions. Int. J. Des. 2012, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonner, E.T.; Friedman, H.L. A Conceptual Clarification of the Experience of Awe: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Humanist. Psychol. 2011, 39, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J.; Fayn, K.; Nusbaum, E.C.; Beaty, R.E. Openness to Experience and Awe in Response to Nature and Music: Personality and Profound Aesthetic Experiences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2015, 9, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; Carmichael, M., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrasvuori, J.; Boberg, M.; Korhonen, H. Understanding Playfulness: An Overview of the Revised Playful Experience (PLEX) Framework. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Design and Emotion (D&E 2010), Chicago, IL, USA, 4–7 October 2010; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiner, K.M.; Laib, M.; Schippert, K.; Burmester, M. Identifying experience categories to design for positive experiences with technology at work. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA ’16), San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, M. The Thing and I: Understanding the Relationship between User and Product. In Funology: From Usability to Enjoyment; Blythe, M., Monk, A., Overbeeke, K., Wright, P., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Hekkert, P. Framework of product experience. Int. J. Des. 2007, 1, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, G.; Sofroniou, N. The Multivariate Social Scientist; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pituch, K.A.; Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 6th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tuch, A.N.; Hornbæk, K. Does Herzberg’s notion of hygienes and motivators apply to user experience? ACM Trans. Comput. -Hum. Interact. (TOCHI) 2015, 22, 16:1–16:24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angeli, A.; Sutcliffe, A.; Hartmann, J. Interaction, Usability and Aesthetics: What Influences Users’ Preferences? In Proceedings of the DIS 2006, University Park, PA, USA, 26–28 June 2006; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tractinsky, N.; Hassenzahl, M. Arguing for Aesthetics in Human-Computer Interaction. I-Com 2006, 4, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partala, T. Psychological Needs and Virtual Worlds: Case Second Life. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2011, 69, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkay, S.; Adinolf, S. The Effects of Customization on Motivation in an Extended Study with a Massively Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Game. Cyberpsychology 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brand-Correa, L.I.; Steinberger, J.K. A Framework for Decoupling Human Need Satisfaction From Energy Use. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 141, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, M.; Hassenzahl, M.; Platz, A. Dynamics of User Experience: How the Perceived Quality of Mobile Phones Changes over Time. In User Experience-Towards a Unified View, Workshop at the 4th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Oslo, Norway, 14–18 October 2006; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 74–78.

- Kujala, S.; Roto, V.; Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K.; Karapanos, E.; Sinnelä, A. UX Curve: A Method for Evaluating Long-Term User Experience. Interact. Comput. 2011, 23, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nostalgia | “wow, that reminds me of …”. One may experience wow because of pleasant reminiscence or memories, e.g., looking at photos of the family’s holiday in an album, or visiting an ancient, foreign place that you dreamt of as a child. |

| Fantasy | “wow, this makes me think of …”. One may experience wow because of pleasant fantasies, e.g., reading a Harry Potter book (‘preferred the book over the film, because it felt more active’), or fantasizing about video projection on the wall at home. |

| Sensorial experience | “wow, this … feels terrific”. One may experience wow because of pleasant physical activities or sensations, e.g., sailing on a boat, salsa dancing, or watching The Matrix and almost immersing physically in it. One respondent called this flow. |

| Amazement | “wow, I didn’t know is possible”. One may experience wow because of an unexpected and pleasant functionality, e.g., finding the phone number of a taxi on i-mode™ ‘in the middle of nowhere’, or the first time use of a car navigation system. |

| Surprise | “wow, I like this new …”. One may experience wow when one likes to be surprised, e.g., buying music without knowing it. Surprise and amazement are slightly different: surprise refers to the person, whereas amazement refers to product or service. |

| Beauty | “wow, that… is so beautiful”. One may experience wow because of the aesthetical qualities of an object or environment, e.g., a handbag with beautiful color and shape (‘I’ve got to have it’), or mobile phone (‘icy blue, with blue stripe and blue lights’). |

| Exclusivity | “wow, this … is unique”. One may experience wow when an event, product or service is rare or (almost) unique, e.g., a total eclipse of the sun, or participating in a sports championship and being very close to a sports star. |

| Budget | “wow, this …is cheap”. One may experience wow when a product or service is cheaper than was expected, e.g., buying a pair of blue jeans for 11 euro only, or receiving a picture on a mobile phone without paying for it. |

| Comfort | “wow, this … is so easy”. One may experience wow because a product or service is very easy, accessible or helpful, e.g., speech recognition on a PC, or a digital camera (‘take many pictures, put some on the web, have them printed’). |

| Mastery | “wow, I managed or learned to do this …”. One may experience wow when doing something that one was not able to do before, e.g., dressage for horse riding, singing solo in a choir, or hacking a mobile phone (may include creative self-expression). |

| Connectedness | “wow, we are … together”. One may experience wow when one feels connected to others, e.g., receiving an SMS, sharing web log messages, or creating a SMS chain poem. Connectedness may be physical, digital real-time, or digital time-shifted. |

| Own world | “wow, this is my personal …”. One may experience wow because of a pleasant private sensation, e.g., being with a horse, or going outside to skate with a Walkman on. This wow may include creative self-expression and escapism. |

| Care | “wow, it feels good to care for …”. One may experience wow when providing care to another, e.g., talking over the phone or MSN (former Windows Live Messenger), or playing with a Tamagotchi, or caring for a horse. This wow is similar to either connectedness or to own world. |

| Competition | “wow, we play …”. One may experience wow when playing with others (stimulating each other, not fighting), e.g., playing Xbox Live with friends across the country, or sailing in a competition. Competition may coincide with connectedness. |

| Inspiration | “wow, I feel inspired to do …”. One may experience wow when feeling inspired to do something. This wow was not mentioned in these wordings during field research—maybe respondents referred to it as fantasy, amazement, surprise or beauty. |

| Autonomy | That my choices were based on my true interests and values. Free to do things my own way. That my choices expressed my “true self.” |

| Competence | That I was successfully completing difficult tasks and projects. That I was taking on and mastering hard challenges. Very capable in what I did. |

| Relatedness | A sense of contact with people who care for me, and whom I care for. Close and connected with other people who are important to me. A strong sense of intimacy with the people I spent time with. |

| Self-actualization—meaning | That I was “becoming who I really am”. A sense of deeper purpose in life. A deeper understanding of myself and my place in the universe. |

| Physical thriving | That I got enough exercise and was in excellent physical condition. That my body was getting just what it needed. A strong sense of physical well-being. |

| Pleasure—stimulation | That I was experiencing new sensations and activities. Intense physical pleasure and enjoyment. That I had found new sources and types of stimulation for myself. |

| Money—luxury | Able to buy most of the things I want. That I had nice things and possessions. That I got plenty of money. |

| Security | That my life was structured and predictable. Glad that I have a comfortable set of routines and habits. Safe from threats and uncertainties. |

| Self-esteem | That I had many positive qualities. Quite satisfied with who I am. A strong sense of self-respect. |

| Popularity—influence | That I was a person whose advice others seek out and follow. That I strongly influenced others’ beliefs and behavior. That I had strong impact on what other people did. |

| sympathy | To experience an urge to identify with someone’s feelings of misfortune or distress. |

| kindness | To experience a tendency to protect or contribute to the well-being of someone |

| respect | To experience a tendency to regard someone as worthy, good, or valuable. |

| love | To experience an urge to be affectionate and care for someone. |

| admiration | To experience an urge to prize and estimate someone for their worth or achievement. |

| dreaminess | To enjoy a calm state of introspection and thoughtfulness. |

| lust | To experience a sexual appeal or appetite |

| desire | To experience a strong attraction to enjoy or own something. |

| worship | To experience an urge to idolize, honor, and be devoted to someone |

| euphoria | To be carried away by an overwhelming feeling of intense joy. |

| joy | To be pleased about (or taking pleasure in) something or some desirable event |

| amusement | To enjoy a playful state of humor or entertainment |

| hope | To experience the belief that something good or wished for can possibly happen. |

| anticipation | To eagerly await an anticipated desirable event that is expected to happen |

| surprise | To be pleased by something that happened suddenly, and was unexpected or unusual. |

| energized | To enjoy a high-spirited state of being energized of vitalized. |

| courage | To experience mental or moral strength to persevere and withstand danger or difficulties. |

| pride | To experience an enjoyable sense of self-worth or achievement. |

| confidence | To experience faith in oneself or one’s abilities to achieve or to act right |

| inspiration | To experience a sudden and overwhelming feeling of creative impulse. |

| enchantment | To be captivated by something that is experienced as delightful or extraordinary. |

| fascination | To experience an urge to explore, investigate, or to understand something |

| relief | To enjoy the recent removal of stress or discomfort. |

| relaxation | To enjoy a calm state of being free from mental or physical tension or concern. |

| satisfaction | To enjoy the recent fulfillment of a need or desire. |

| Item | Statement ENG/GER (Original) | Theoretical Background |

|---|---|---|

| Exceeding of expectations | My expectations were exceeded by far. Meine Erwartungen wurden bei Weitem übertroffen. | Wow experiences are assumed to be unexpected or surpass the users’ expectations [1,2,4,7,8,9]. The item statement was strengthened with the addition of “by far” to obtain a more nuanced result. |

| Ease of use | The product was easy to use. Das Produkt war einfach zu bedienen. | A product’s usability, accessibility, and ease of use are considered to facilitate or block positive user experience [12]. Steen et al. [2] proposed this as a wow factor, and Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila et al. [7] suggested that flawless usability is required to facilitate wow experiences. |

| Usefulness | The product seemed very useful to me. Das Produkt erschien mir sehr nützlich. | Utility and perceived usefulness of the product together comprise a main factor contributing to use acceptance in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) [19]. |

| Aesthetics | I was delighted by the product’s visual design. Ich war vom Erscheinungsbild des Produkts begeistert. | Beauty is considered to be primarily related to hedonic quality [3] and contributes to the emotional experience [26]. Steen et al. [2] proposed beauty as a wow factor, and Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila et al. [7] suggested that pleasant aesthetics are necessary to facilitate wow experiences. |

| Versatility | I was amazed by how much I could do with the product. Ich war erstaunt davon, wie viel ich mit dem Produkt machen konnte. | Versatility refers to a high range of functions, serving many purposes (maybe more than the user actually needs), and is based on the wow factor amazement [2]. Hassenzahl [25] suggested that “functionality not yet used but interesting will be perceived as hedonic” (p. 5). |

| Success | I felt a sense of accomplishment while using the product. Ich hatte Erfolgsgefühle bei der Nutzung des Produkts. | Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila et al. [7] reported that wow experiences often involved the feeling of success, which may be the result of fulfillment of the need for competence. |

| Joy | I felt great joy and delight while using the product. Ich hatte große Freude und Vergnügen bei der Nutzung des Produkts. | This item is based on the emotion of joy from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Joy was found to be strongly connected to wow experiences [11]. |

| Fascination | I felt the desire to explore, investigate, or understand the product. Ich hatte den Drang, das Produkt zu erkunden, zu erforschen oder zu verstehen. | This item is based on the emotion of fascination from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Fascination was found to be the strongest emotion connected to wow experiences [11] and was part of the previous wow definition [4]. |

| Memorability | I can still remember this experience clearly. Ich erinnere mich noch sehr gut an dieses Erlebnis. | Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila et al. [7] found that wow experiences stay memorable, even after months or years. |

| Surprise | I was surprised by unexpected or unusual elements of the product. Ich bin auf unerwartete und ungewöhnliche Eigenschaften des Produkts gestoßen. | This item is based on the emotion of surprise from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Surprise was found to be the third strongest emotion connected to wow experiences in [11] and was part of the previous wow definition [4]. |

| Speechlessness | The experience made me speechless for a moment. Das Erlebnis hat mich für einen Moment sprachlos gemacht. | According to a statement made by a participant of the item optimization tests, “For me, it always involves a brief moment of speechlessness, you need some time to find words for it.” |

| Stimulation (2/2) | Using the product was an entirely new experience for me. Die Nutzung des Produkts war eine ganz neue Erfahrung für mich. | Based on the results of the pilot survey, wow experiences are commonly caused by products that are completely new to the user. This is related to the psychological need for stimulation [15]. Stimulation was found to be the most intense need connected to wow experiences [11]. |

| Action mode | During the experience, I tried out the product without a specific goal. Ich habe das Produkt bei dem Erlebnis ohne bestimmtes Ziel ausprobiert. | This item refers to exploration of the product out of curiosity without a certain task or objective. Based on action mode [25], using the product is an end in itself. The opposite is goal mode, in which specific goals are pursued through product usage [25]. |

| Enchantment | I was enchanted or charmed by the product. Ich war von dem Produkt eingenommen oder bezaubert. | This item is based on the emotion of enchantment from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Enchantment was considered relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Euphoria | I was carried away by a feeling of overwhelming joy. Ich wurde von überwältigender Freude mitgerissen. | This item is based on the emotion of euphoria from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Euphoria was considered relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Inspiration | The product inspired or encouraged me to be creative. Das Produkt hat mich inspiriert oder dazu ermuntert, kreativ zu werden. | This item was based on the emotion of inspiration from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Inspiration was considered relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Satisfaction | The product fulfilled my wish or need. Das Produkt hat mir einen Wunsch oder ein Bedürfnis erfüllt. | This item was based on the emotion of satisfaction from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Satisfaction was considered relevant to wow experiences [11]; this item also refers to the fulfillment of latent or unexpected needs, see [1]. |

| Autonomy (1/2) | While using the product, I could proceed freely and autonomously. Bei der Nutzung des Produkts konnte ich frei und selbstbestimmt vorgehen. | This item was based on the psychological need for autonomy [15], which was found to be one of the needs relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Competence (1/2) | During the experience, I was faced with challenges. Bei dem Erlebnis wurde ich vor Herausforderungen gestellt. | This item was based on the psychological need for competence [15], which was found to be one of the needs relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Stimulation (1/2) | The product was entertaining or posed a pleasant diversion. Das Erlebnis stellte für mich eine angenehme Abwechslung oder Unterhaltung dar. | This item was based on the psychological need for stimulation [15], which was found to be the most relevant need for wow experiences [11]. |

| Luxury | I perceive using or owning the product as a luxury. Ich empfinde die Nutzung oder den Besitz des Produkts als Luxus. | This item was based on the psychological need for luxury [15], which was found to be one of the needs relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Self-actualization/meaning (1/2) | I have/had the desire to tell others about this experience. Ich hatte/habe das Bedürfnis, anderen von diesem Erlebnis zu erzählen. | In informal interviews, some participants stated that they wanted to tell their friends about the experience or had even signed up for the study because they had been told about it by excited previous participants. This aspect was added as an exploratory item, considered to represent meaningfulness and the need for self- actualization/meaning. |

| Desire | I have/had the desire to own the product. Ich hatte oder habe das Verlangen, das Produkt selbst zu besitzen. | This item was based on the emotion of desire from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Desire was part of the previous wow definition [4]. |

| Energized | I felt energized, excited, and lively. Ich fühlte mich voller Energie, aufgeregt und lebendig. | This item was based on the emotion of being energized from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Energized was considered relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Control | During the experience, I had the feeling of control. Bei dem Erlebnis hatte ich das Gefühl von Kontrolle. | Perceived control over the system, the environment, or other people has been referred to as a wow design principle [1], as a playful experience [20], and also in the context of positive experiences at work [21]. |

| Autonomy (2/2) | I busied myself with the product out of my own interest. Ich beschäftigte mich mit dem Produkt aus eigenem Interesse. | This item was based on the psychological need for autonomy [15], which was found to be relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Competence (2/2) | I successfully mastered tasks or difficulties. Ich meisterte erfolgreich Aufgaben oder Schwierigkeiten. | This item was based on the psychological need for competence [15], which was found to be relevant to wow experiences in [11]. |

| Self-actualization/meaning (2/2) | During the experience, I got to know myself better. Bei dem Erlebnis lernte ich mich selbst besser kennen. | This item was based on the psychological need for self-actualization/meaning [15], which was found to be relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Anticipation | I was already looking forward to trying out the product beforehand. Ich habe mich schon im Voraus darauf gefreut, das Produkt auszuprobieren. | This item was based on the emotion of anticipation from the 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Anticipation was considered to be relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Amusement | The product entertained me with its humor or playfulness. Das Produkt hat mich mit seinem Humor oder seiner Verspieltheit unterhalten. | This item was based on the emotion of amusement from the typology of 25 positive emotions in human-product interaction [16]. Amusement was considered to be relevant to wow experiences [11]. |

| Item | Factor 1: Hygienes | Factor 2: Goal Attainment | Factor 3: Uniqueness | Factor 4: Emotional Fingerprint | Factor 5: Relevance | Factor 6: Inspiration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ease of use | 0.479 | |||||

| usefulness | 0.478 | |||||

| autonomy (1/2) | 0.587 | |||||

| aesthetics | 0.412 | |||||

| competence (1/2) | −0.478 | |||||

| competence (2/2) | −0.529 | |||||

| success | −0.616 | |||||

| versatility | −0.449 | |||||

| surprise | 0.644 | |||||

| unexpectedness | 0.604 | |||||

| speechlessness | 0.588 | |||||

| stimulation (2/2) | 0.548 | |||||

| memorability | 0.489 | |||||

| meaning (1/2) | 0.456 | |||||

| amusement | 0.608 | |||||

| joy | 0.532 | |||||

| energized | 0.516 | |||||

| anticipation | 0.420 | |||||

| euphoria | 0.418 | |||||

| action mode | 0.648 | |||||

| desire | −0.634 | |||||

| satisfaction | −0.476 | |||||

| inspiration | 0.794 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kulzer, M.; Burmester, M. Towards Explainable and Sustainable Wow Experiences with Technology. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4030049

Kulzer M, Burmester M. Towards Explainable and Sustainable Wow Experiences with Technology. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2020; 4(3):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4030049

Chicago/Turabian StyleKulzer, Manuel, and Michael Burmester. 2020. "Towards Explainable and Sustainable Wow Experiences with Technology" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 4, no. 3: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4030049

APA StyleKulzer, M., & Burmester, M. (2020). Towards Explainable and Sustainable Wow Experiences with Technology. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 4(3), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4030049