Abstract

This paper presents the practice of designing mediation technologies as artistic tools to expand the creative repertoire to promote contemplative cultural practice. Three art–science collaborations—Mandala, Imagining the Universe, and Resonance of the Heart—are elaborated on as proof-of-concept case studies. Scientifically, the empirical research examines the mappings from (bodily) action to (sound/visual) perception in technology-mediated performing art. Theoretically, the author synthesizes media arts practices on a level of defining general design principles and post-human artistic identities. Technically, the author implements machine learning techniques, digital audio/visual signal processing, and sensing technology to explore post-human artistic identities and give voice to underrepresented groups. Realized by a group of multinational media artists, computer engineers, audio engineers, and cognitive neuroscientists, this work preserves, promotes, and further explores contemplative culture with emerging technologies.

1. Introduction

Tibetan culture, which uniquely embraces the legacy of both Indian and Chinese Buddhism [1], has stunning arts such as the Mandala Sand Art [2], monastic throat-singing [3], and Cham dance. Compared with its contribution to the world, such as its contemplative techniques and improvement of well-being [4,5,6], Tibet’s intangible heritage is highly underrepresented due to many reasons [7,8,9] that are beyond the scope of this article. However, being a Tibetan Buddhist who has been studying and practicing both Jonang tradition, Nyingma tradition, and Kagyu tradition with the H.H. 17th Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje, the voluntary Khenpo Sodargye Rinpoche, Tulku Tashi Gyaltsan Rinpoche, and Chakme Rinpoche for 20 years, and, at the same time, being a media artist and an interdisciplinary researcher, my passion and the ultimate goal is to externalize my practice-based understanding of Tibetan contemplative culture and then to promote it through my work in music composition, vocal expression, multimedia performance, and technology development.

Deeply anchored in Tibetan contemplative culture, my research situates the design, development, and evaluation of media technologies. These innovative technologies are then used as artistic tools to create novel expressions to make a social impact. By exploring the healing power of the voice, I focus on how vocalists can enhance their vocal expressions with technology that facilitates cross-cultural communication and contemplative practices. By initiating and fostering art-science collaborations and turning the multimedia technology design, development, and implementation research into art practices, I hope to inspire other artists, technologists, and scholars to join me on the journey of promoting any kind of meaningful underrepresented cultural values through their work.

From an engineering perspective, I design and develop digital musical instruments (DMI) and human-computer interactive systems, which implement machine learning techniques and 3D tracking to capture and identify the body movement of a vocalist. The vocalist’s gestural data are simultaneously mapped into audio/visual events that activate vocal processing effects, such as reverberation and chorus, and manipulate computer graphics in a live performance.

From a theoretical perspective, I investigate existing theories in the context of music subjectivity [10,11,12], affordance [13,14,15], aesthetic and economic efficiency [16], culture constraints and social meaning-making [17,18,19,20], and conceptualize this body of knowledge into a series of DMI design principles.

From a scientific perspective, I facilitate quantitative and qualitative human subject research to evaluate my design principles and examine the body–mind mappings, from gestures to sound perception. Different from typical DMI evaluations that examine mapping relationships through user studies [21], my original evaluation framework provides scientific justification for validating DMI and body-sound mappings in electroacoustic vocal performance from the audience’s perspective. This unique approach provides empirical evidence for identifying the audience’s degree of musical engagement from synchronization, to embodied attuning, and to empathy—the human connections [22].

2. Materials and Methods

Given the interdisciplinary nature of my work and my long-term engagement with international computer science, music, and media arts research institutions, such as the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at Stanford University, I often work closely with researchers in computer science, electronic engineering, and neuroscience fields. I aim to connect research and artistic practices within and outside of academic settings.

As the engineer Richard Hamming pointed out [23], it is insignificant if novelty and innovation make no cultural impact on human history. Through implementing our designed innovative technologies to compose proof-of-concept multimedia art pieces, I strive to create intriguing work that translates ancient Tibetan contemplative philosophy and culture to both a musical and spiritual experience. The aspiration of my work is to capture the natural forms of human expression and embody them artistically in real-time by bringing an ancient Tibetan art form and its contemplation to the digital world and the 21st century.

In the following sections, I will elaborate on three case studies and scientific research on body-mind connection to demonstrate how my proof-of-concept audio-visual pieces serve as a direct result of interdisciplinary collaborations between musicians, visual artists, technologists, and scientists. Our collaborative goal is to address the questions of how media arts technology and new artistic expressions can expand the human repertoire, and how to promote underrepresented culture and cross-cultural communication through these new expressions.

2.1. The Virtual Mandala

The word “Mandala” comes from Sanskrit, meaning “circle.” It represents wholeness, and it can be seen as a model for the organizational structure of life itself. In Tibet, as part of a spiritual practice, monks create mandalas with colored sand [24]. The creation of a sand mandala may require days or weeks to complete. When finished, the monks gather in a colorful ceremony, chanting in deep tones (Tibetan throat singing) as they sweep their Mandala sand spirally back into nature. This symbolizes the impermanence of life and the world.

The aspiration of this project, Virtual Mandala, was to capture the natural forms of human expression and embody them artistically in real-time by bringing the above ancient Tibetan art forms and their contemplation to the digital world. In this project, I aimed to create an intriguing piece that translates this ancient philosophy to a multimedia art and cultural experience through augmented reality and music composition. I computer-simulated and choreographed a Tibetan Sand Mandala vocal and instrumental composition. The performer activated, with her arms, 4.5 million particles using a physical computing and motion-tracking system [25,26].

To realize this piece, my collaborator introduced me to an open-sourced graphic and dynamic modeling framework, CHAI3D [27], an open source set of C++ libraries designed to create sophisticated applications that combine computer haptics, visualization, and dynamic simulation, to simulate the physical interaction between the captured hand motions of the performer and the small mass particles composing the virtual Mandala.

The software libraries support many commercially-available multi-degree-of-freedom input devices, including the Razor Hydra. The framework provides a convenient interface for loading images and 3D model files. Furthermore, the libraries also support tools to easily create complex physical systems that include particle, rigid body, and deformable-based models. An XML file format was used to describe scene graphs and animation sequences that were loaded by the graphic display module. These files described the objects composing the virtual environment and their physical properties, as well as the interactions, events, and behaviors that can be triggered by the performer.

The mapping between the hands of the performer and their models in the simulation was performed using a mapping technique [28] called workspace expansion, which relies on progressively relocating the physical workspace of the devices mapped inside of the virtual environment towards the operator’s area of activity without disturbing his or her perception of the environment. This approach allowed me to interact with high accuracy in a very large virtual environment while moving my hands within a reasonably small workspace.

The audio processing application, designed using the ChucK programming language, interprets MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) signals from the motion-tracking module and activates a selection of audio filters and generators according to the desired musical expression. The application communicates all input and output audio signals by using the Unicorn 828mkII interface, which supports multiple channels that include both voice and electronic instruments. Because of the real-time nature of the technology, the interface delivers near-instant response between the hand motions generated by the operator and the actions commanded by the computer.

The creation of interactive visuals for live music performances bears close resemblance to music videos, but is typically meant to be displayed as back-plate imagery that adds a visual component to the music performed onstage in real-time. The intuitive relationship between music and the visuals’ dynamic changes over time is crucial for this artistic creation. Graphic deformations, light shows, and/or interactive animations can be used in combination with audio tracks to convey setting and place, action, and atmosphere of a composition. To realize this performative audio-visual interaction, I designed a human interface to easily animate two- and three-dimensional interactive and dynamic environments that respond to hand motions captured by a 3D magnetic motion sensing tracker. This design was used to dynamically simulate the virtual Mandala construction and deconstruction.

The piece included three movements: construction, climax, and destruction. At the beginning of the piece, hand motions from the vocalist were directed to initiate the Construction of the virtual Mandala. Music composition for this part was developing and calm, which included Tibetan monastic chants of Four Refuges and Padmasambhava mantras, computer music implementing additive synthesis and Frequency Modulation synthesis techniques to create an ocean–wave-alike soundscape, with a dolphin-whistle sound simulation that makes high notes dynamically move up and down with the body movement. The backbone of the piece was made of rhythmic samples in Logic Pro with outputs and lives guitar processor inputs, routed through a Mark of the Unicorn 828mkII interface for 10 channels of spatialized output. Live guitar sounds were generated by a Fractal Audio AxeFX Ultra processor. Mixed sounds of electronic guitar, rhythmic drumming, Buddhist chanting, synthesized sound waves, and celleto start to create and build up an imaginary world, from tranquility and emptiness to intense passion and complex glamor.

During the Climax, musicians were focusing on musical improvisation, while the virtual Mandala was self-directed and presented animation, such as rotation, twisting, and glitter effects, in an ecstatic expression. The mantra of Kalachakra was sung to emphasize the circle/wheel of life, time, and space. Experimental low-tone throat singing and explosions of violent soprano interjections come to symbolize the extreme conflicts and ecstasy in life, the extraordinary highs and lows, the sharp rises and falls of life as it is experienced, ending with a sharp fade out into the deconstruction of the Kalachakra mandala. The Destruction, which underscores the eternal nature of impermanence, occurs near the coda of the audio-visual piece through the hand motions of the singer.

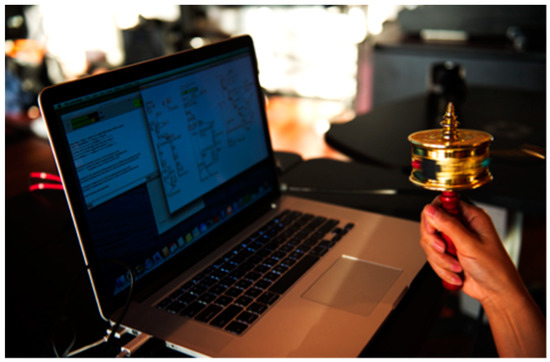

In 2013, as part of a multimedia live performance created at Stanford University and an invited performance at the Third International Buddhist Youth Conference in the Hong Kong Institute of Education, an interactive display of sand Mandala was dynamically simulated and choreographed with the vocal and instrumental compositional improvisation. The first performance at Stanford University took place before an audience of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and researchers, while the second performance occurred in Hong Kong, before an eastern Buddhist audience. Both audiences showed enthusiasm for the cultural content and were fascinated about the technologies that were implemented to realize this piece, both during and after the concerts. Some of the audience used the word “magic” to describe the piece and their experience of watching this performance. In 2017, I completed the postproduction and realized a fixed audio-visual piece of this work. The performance piece and the fixed-media piece were well received by both the Western audience and the Tibetan diaspora. Figure 1 shows a moment of the Mandala Premier at Stanford University in 2013.

Figure 1.

Virtual Mandala live performance (Supplementary Materials).

2.2. Tibetan Singing Prayer Wheel

The design aspiration of the Tibetan Singing Prayer Wheel was to capture similar circular movements from both operating a Tibetan prayer wheel and playing a Tibetan singing bowl, and then logically mapping these motion inputs to generate sounds and to process voice, thus musically creating embodiment in human–computer interaction. I also discuss my proposed principles that were used to realize the DMI and further clarify how these design principles can be used in a real-life scenario.

A Prayer Wheel consists of a free-spinning cylinder attached to a handle, which contains a multitude of prayers printed on a long roll of paper; it can be made in a wide range of sizes, styles, and materials. It is believed that spinning the wheel with a simple and repetitive circular motion induces relaxation and calm in the person performing the motion. A prayer wheel is often spun while chanting mantras. The Tibetan Singing Bowl is originally a ritual instrument in Buddhism. It is used during meditation. Rubbing a wooden stick in a circular motion around the outer rim of the metal bowl at the appropriate speed and pressure excites a harmony of resonances. Due to its soothing and meditative musical nature, it is widely used in music therapy. Both of these two instruments share the same ancient Buddhist philosophy in Kalachakra, or the idea that time, life, and the universe are cyclical [29].

Inspired by the Tibetan singing bowl, the prayer wheel, and the shared circular movement playing these instruments, Tibetan Singing Prayer Wheel is a new musical interface that utilizes the same circular hand motions that operate the two instruments that are discussed above, and then combine sounds and the gestures, along with voice modulation, using electronics and software. In this work, I strived to create an agent that translates the ancient Tibetan Buddhist philosophy into a day-to-day experience, through embodied musical experience and interactive arts, that prompt the next generation to rediscover those transcendent cultural heritages. This case study demonstrates how culture plays a crucial role in DMI design. In my design, I hoped to preserve these associations while adding digitized gestural mapping and control.

At the aesthetic and compositional level, inspired by the thematic connection of the similar circular gestures of spinning the Prayer Wheel and rubbing the Singing Bowl, I designed a physical-motion-sensing controller that maps the sensed circular motions (of the wheel spinning) and the steady raising–lowering gesture to a variety of outputs, including the corresponding virtual circular motions (e.g., exciting the modeled bowl), changes in vocal processing, and amplitude modulation. Furthermore, the intuitive haptic feedback from the prayer wheel plays a crucial role in guiding the user to pick up the instrument, understand the functionality of its interface, and master the whole system in a relatively short period of time. The responsive nature of the whole haptic-audio system allows the users to have an intimate, engaging, and satisfying multimedia experience.

On 21 November 2014, sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and Stanford University, a live-performance telematics concert named “Imagining the Universe—Music, Spirituality, and Tradition” was held at the Knoll Hall at Stanford University. This concert was an international collaboration that was broadcast live via the Internet, connecting musicians and scholars at six research institutions from Stanford University, Virginia Tech, UC Santa Barbara, University of Guanjuato (Mexico), to Shangri-La Folk Music Preservation Association and Larung Gar Five Sciences Buddhist Academy (Sichuan Province, China). The concert was dedicated to the Venerable Khenpo Sodargye Rinpoche [30], an influential Tibetan Buddhist scholar. As a disciple who has followed Khenpo Sodargye Rinpoche’s teaching for more than a decade, it was my honor to organize this special event with the collaborations of my colleagues at Stanford University. Khenpo Sodargye graciously attended the concert along with approximately 400 other audience members. This concert combined research, artistic creation, and performing art in connection with the integration of cutting-edge technology, building cross-cultural relationships through the lens of artistic and contemplative practice and interdisciplinary collaboration [3]. The event was part of Stanford’s yearlong project of “Imagining the Universe.” In collaboration with NASA, this was a campus-wide interdisciplinary consortium exploring the connection between the sciences and the arts.

The technology component of this project explored ways of connecting cultures and collaborative artistic partners over long distances, through the use of the Jacktrip [31] application for online jamming and concert technology. Jacktrip was first developed in the early 2000s. It is an open source, Linux, and Mac OSX-based system, used for multi-machine network performance over an Internet connection. Jacktrip supports any number of channels of bidirectional, high-quality, low-latency, and uncompressed audio-signal streaming [32]. The technology explores ways of connecting cultures and collaborative artistic partners over long distances. Musicians have increasingly started using this emerging technology to play tightly-synchronized music with other musicians who are located in different cities or countries. Without paying significant transportation costs, we exchanged musical ideas, rehearsed, recorded, and improvised together in different geological locations and for the final concert presentation.

We conducted four rehearsals, which led to the final concert. Approximately 400 people attended the concert. The Tibetan Singing Prayer Wheel was successfully integrated into multiple pieces with traditional Buddhist instruments, vocalists, and a variety of acoustic and electronic Western instruments. An illustration of the performance organized by the Stanford University and NASA is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

NASA–Stanford “Imagining the Universe“ concert (Supplementary Materials).

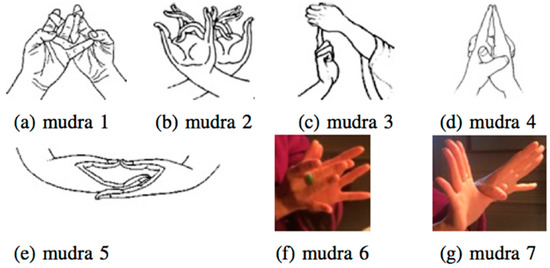

As part of this concert’s research contribution and a gift that is dedicated to the Venerable Khenpo Sodargye Rinpoche, my research team and I built the Tibetan Singing Prayer Wheel (TSPW), combining both the meditative and musical associations of two Tibetan sacred instruments into one novel digital musical instrument (DMI). The cultural heritage and meditative associations of the Tibetan prayer wheel, Tibetan singing bowl, and Buddhist chanting inspired this instrument [33]. In this design, I hoped to preserve these associations while adding digitized gestural mapping and control. At the aesthetic and compositional level, inspired by the thematic connection of the similar circular gestures of spinning a prayer wheel and rubbing a singing bowl, I designed a physical-motion-sensing controller that maps sensed circular motions (wheel spinning) and a steady raising/lowering gesture to a variety of outputs, including corresponding virtual circular motions (exciting the modeled bowl), changes in vocal processing, and amplitude modulation, as shown in Figure 3. Specifically, the performer gives the system three inputs: Vocals via a microphone, spinning and motion gestures from an electronically-augmented prayer wheel, and button presses on a four-button RF transmitter to toggle sound processing layers. These inputs activated a virtual singing bowl, real-time sound synthesis, and voice processing. Finally, the resulting audio signal was amplified and projected into the performance space.

Figure 3.

A Tibetan Singing Prayer Wheel digital musical instrument.

As mentioned previously, the gesture of spinning a prayer wheel is traditionally associated with Buddhist meditative practice. Thus, the spinning gesture has an existing natural mapping to the sound of rubbing a singing bowl. The gestures of raising and lowering the wheel build the audience’s expectation that some element of the performance will increase or decrease. I chose to link these gestures in a one-to-many mapping strategy, using the same gesture to control multiple compositional layers, to enrich the vocalist’s musical expression in a simple way. A physical model simulated the singing bowl, while a modal reverberator and a delay-and-window effect processed the performer’s vocals. This system was designed for an electroacoustic vocalist interested in using a solo instrument to achieve performance goals that would normally require multiple instruments and activities.

As a novel DMI, the TSPW was successfully integrated into multiple pieces with Western classical instruments, Tibetan traditional instruments, and a variety of electronic/digital instruments.

In early 2015, we first applied the TSPW to a sound installation at the Maker Faire, located in Northern California. A broader user group of around 200 people, including laypersons, children, elderly, and people who enjoy technology at all ages, participated in this sound installation. An illustration of the sound installation at the Maker Faire 2015 in the Silicon Valley is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Interactive sound installation using the TSPW at the Maker Faire, 2015, in California.

A similar sound installation was realized on 29 May 2015 at the California NanoSystems Institute at UC Santa Barbara. Around 100 people participated, with participants consisting mostly of undergraduate and graduate students, researchers, faculty members, and the community members of UCSB and the California NanoSystems Institute. Another two similar sound installations were realized later in the same year, respectively exhibited at UCLA and at NIME 2015 (New Interfaces for Musical Expression) at Louisiana State University’s Digital Media Center. During her keynote speech, Sile O’Modhrain pointed out that the TSPW, which uses gestural control and haptic feedback for designing an intuitive novel musical interface, was one of the “good NIMEs” of the year. Around more than 500 people participated in these other two sound installations. They were mostly students and faculty members, researchers, and community members at the research institutions.

2.3. Resonance of the Heart

The third case study, Resonance of the Heart, was inspired by a “Kōan” story in Chinese Zen Buddhism, called “印心”, which describes a Zen master and his disciple’s thoughts resonant without any verbal communication. This means these two enlightened human beings only communicated through their body–mind attuning in a profoundly lucid way. I have found this penomenon specifically interesting, as this concept aligns with my long-term investigations on body–mind connections through mediation technology development and art-science collaborations. In another word, the unspoken or unsayable body language can connect people and become a significant way of communication.

Indeed, with the assistance of the innovative mediation technology, nowadays artists are entering into an “augmented human” era, which some scholars call the “posthuman era” [34]. Although many scholars concern challenges of artistic identity, ownership issues, and body boundaries in the posthuman era, and some may even have a negative view upon these challenges, I perceive these challenges as opportunities to help human species move forward. Regarding this debate, I agree with Novak’s viewpoint [35], that with setting the humanities as the ultimate goal and end, and with the technology as a means to promote/accomplish excellence in the humanities, we humans can overcome and go far beyond our current human condition. Therefore, posthumans could potentially become better humans if we put greater efforts and faith in this direction. This is also the overall goal of my ongoing research in “Embodied Sonic Meditation”, where I examine how bodily activities can help increase our sonic awareness and open up our creative mind, and how an augmented body equipped with mediation technology can become a part of the art itself or become the artist’s extended body or/and extended mind.

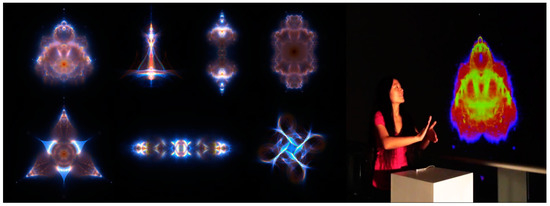

For gestural input and control strategy, I applied ancient Buddhist hand gestures named Mudras [36] that have the hands and fingers crossed or overlapped, as shown in Figure 5, to trigger and manipulate corresponding sonic effects.

Figure 5.

Seven examples of Mudras input gestures and output labels for gestural recognition.

Meanwhile, dynamic hand motions were also mapped to the audio/visual system to continuously control electroacoustic voice manipulations and a gestural data visualization of four-dimensional Buddhabrot fractal deformations. Buddhabrot is a special method of rendering a Mandelbrot fractal. It tracks all the trajectories and renders them to produce the ghostly forms reminiscent of the Siddhārtha Gautama Buddha. A high-resolution four-dimensional Buddhabrot rendering takes a considerable amount of computation power, both on CPU and GPU. Therefore, it is a breakthrough to manipulate it in real-time. The algorithms make the fractal reactive to the performer in real-time. The system provides support for installations from basic desktop settings to multi-display performances.

To realize Resonance of the Heart, I designed an audio-visual system using an infrared sensor to track a series of sophisticated hand motions to real-time control vocal processing and computer simulation. I chose optical sensing technology instead of wearable (e.g., gloves) because I strived to preserve the flexibility of the hands/fingers motion as well as the original beauty of the ancient Mudra performance, which is barehanded. Using a small, non-attached sensor ensures that both the vocalist and audience focus on the vocal-Mudras performance and perceive the sound and body as a whole. Instead of choosing a high-precision but expensive optical sensor, I chose a noisy but affordable sensor, and then conducted a gestural recognition research to optimize the tracking system, using machine-learning techniques. To track and predict the Mudras, I collaborated with Artifitual Intelligence researchers to implement machine-learning algorithms and techniques, such as k-nearest neighbors, support vector machine, binary decision tree, and artificial neural network, to capture complex ritual hand Mudras. The Mudra data were then mapped in real-time to control Tibetan throat singing effect, overtone singing effect, vocal reverberations and granular sonic effects, and a four-dimensional Buddhabrot fractal deformation [37]. Figure 6 shows a glimpse of this ongoing performing art project.

Figure 6.

Mudra-conducted four-dimensional Buddhabrot deformation and sonic art.

Mapping the seven Mudras gestures to trigger seven different meditative sonic outputs, such as different bell and chimes sounds that are often used during mindfulness meditation sessions, was originally impossible for this project as the sensor freezes when two hands are overlapped or out of the tracking range. When the classifier recognizes or, more precisely speaking, predicts a particular Mudra, it sends the detected type to ChucK, which plays the corresponding contemplative sound clip. Thus, these Mudra inputs serve as low-level one-to-one triggers and have the same functionality as normal button inputs. However, from the artistic and user experience perspectives, forming various complex hand gestures, in order to trigger specific sound effects and visuals that are symbolized in a contemplative way, makes this mapping strategy much more engaging than simply pushing a button. The embodied cognitive process makes this Mudras-to-sound process more meaningful, as it inherently involves perception and action and it takes place in the context of task-relevant inputs and outputs.

In Spring 2017, resonance of the Heart was used in teaching an upper division, college-level course named “Embodied Sonic Meditation–A Creative Sound Education,” at the College of Creative Studies (CCS) through its Composition Program at University of California Santa Barbara. The UCSB CCS Music Composition major is geared toward preparing students for graduate school or for careers as professional composers. Students develop their personal compositional vocabularies while building a foundation in composition techniques. Meanwhile, an interactive audio-visual art installation was realized on 1 June 2018 at the California NanoSystems Institute at University of California Santa Barbara. Around 100 people participated, with participants consisting mostly of undergraduate and graduate students, researchers, faculty members, and the community members of UCSB and the California NanoSystems Institute. In October 2018, an electroacoustic live performance was realized at the IEEE VIS Art Program in Berlin, Germany. Around 300 people attended, with audience consisting mostly of computer science researchers, media artists, research psychologists in HCI and in data visualization, faculty members in higher education, and the community members of IEEE VIS. In March 2019, two audio-visual interactive sonic art installations were held at both Berklee College of Music in Boston and Stanford University in Northern California. More than 200 people participated in the interactive installations.

2.4. Embodied Sonic Meditation and Body–Sound/Action–Perception Evaluation

The three case studies provide the fundamentals of “Embodied Sonic Meditation” [38], an artistic practice rooted in the richness of the Tibetan contemplative culture, embodied cognition [36,38], and “deep listening” [39]. This sonic art practice is based on the combination of sensing technology and human sensibility. Through this practice, we encourage people to fully understand and appreciate abstract electric and electroacoustic sounds and how these sounds are formed and transformed (cognitive process), by providing them interactive audio systems that can tightly engage their bodily activities to simultaneously create, sculpt, and morph the sonic outcomes themselves, using their body motions (embodiment). This ongoing project aims to further explore gesture-controlled, vocal-processing DMI design strategies and experimental sound education.

To further examine this artistic practice and formulate a body–mind sound theory, in 2016, I collaborated with cognitive neuroscientists at Stanford University to scientifically study audience perceptions for bodily–sound/action–perception mapping strategies. Particularly, we applied TSPW to an evaluation case study to conduct human-subject research, with the primary goal of validating the mapping design and control strategies for the TSPW’s real-time voice processing. We facilitated quantitative and qualitative research to evaluate the design principles and examine the body–mind mappings, from gestures to sound perception. We also examined the way that a TSPW maps horizontal spinning gestures to vocal processing parameters. Our proposed methodology differs from typical DMI evaluations that examine mapping relationships through user studies [21], because mine was built on O’Modhrain’s [40] framework. It evaluates a DMI and its body–sound/action–perception mappings from the audience’s perspective. This approach has been little studied, and our research is the first empirical evaluation of a DMI for augmenting electroacoustic vocal performance from the audience’s perspective.

We hypothesize that the levels of perceived expression and audience engagement increase when the mapping is (1) synchronized (such that the sensed gestures in fact control the processing in real-time) and (2) intuitive. I composed and filmed six songs with the singer simultaneously using the TSPW. In two experiments, two alternative soundtracks were made for each song. Experiment 1 compared the original mapping against a desynchronized alternative; Experiment 2 compared the original mapping (faster rotation causing a progressively more intense granular stutter stuttering effect on the voice) to its inverse. All six songs were presented to two groups of participants, randomly choosing between alternate soundtracks for each song. This method eliminated potential variability in the perceived expressiveness of different performers and videos. Responses were evaluated via both quantitative and qualitative survey and questionnaire. Detailed experimental methodology can be reviewed in [41].

3. Results

3.1. Virtual Mandala

Through the Mandala media art collaboration, I created a quick, yet rich presentation to simulate the Tibetan Mandala sand arts with musical expression; I aesthetically explored the ancient Buddhist philosophy of impermanence. The primer was held at Stanford University, and many other film festivals where this piece was played are in the western world. Most of the audience were from the younger generation. I strived to increase the visibility of traditional Tibetan cultural practices to the “twitter generation” and millenniums. Through this way, I hoped that I could create a new path to guide them to rediscover those transcendent human treasures from the Eastern world. By combining state-of-the-art technology in computer simulation and human interaction with ancient Eastern philosophy and Tibetan Buddhist art, I demonstrated the motivation, compositional structure, and methodology to achieve my aesthetic and technical goals of the multimedia live performance Mandala piece. Repeated performances of this piece with multiple audiences confirmed not only the successful application of this technology, but also the ability of this technology to work with music to bring to life ancient art forms and philosophies for worldwide modern audiences. These preliminary results validated the intuitive design of this application and its capacity to respond with real-time audio-visual performances, and confirmed my original idea toward exploring natural human motion and gesture as an effective and instinctive way to enrich musical and artistic expressions. Denver Art Museum’s Asian Art Collection recently collected this audio-visual piece’s fixed media version.

3.2. Tibetan Singing Prayer Wheel

The “Imagining the Universe” concert provided evidence of strong theatricality when using TSPW; it also showed the added expressive possibilities that TSPW provides to musicians. The mapping relationship between the vocalist’s dramatic gestures and the musical expression was transparent to the audience; the mapping of the spinning of the prayer wheel to the sound of the singing bowl was natural. Interestingly, 36 audience members came by to spin the TSPW after the performance and showed great interest in playing the TSPW. This positive feedback from the audience motivated us to conduct two follow-up projects: One was a series of sound installations, and the other one was an empirical study on evaluating our DMI and bodily–sound/action–perception mapping design. The three art installations at Makerfaire, California NanoSystems Institute, and NIME provided evidence of the success of the design, input, and control strategies of TSPW that can meet a broader users’ satisfaction.

From my observation of the TSPW installations, using real-time body movement/gesture to control and modify a sound’s properties helped people to experience sound in an intimate, conscious, and meditative way. Most of the participants seemed to be able to catch subtle changes of the sound that the prayer wheel made with their own gestural control and physical interaction. With the haptic feedback that the TSPW naturally provides, participants can easily pick up the instrument and play around with it, understand what it does, and how to be creative with it in an engaging way.

Overall, participants’ engagement with sound by using the TSPW was positive when they generated and affected sounds by using their own gestures and body movements. Playing TSPW provides an intuitive way to connect users’ physical movements to interactive sonic experience, as they are making, and “aesthetically” appreciating, perceiving, and enjoying sound with their own physical form. This series of installations was the first step towards the scientific validation of the TSPW and my research in bodily–sound/action-perception mapping strategies for real-time electroacoustic vocal performance, especially for identifying the audience’s degree of musical engagement.

3.3. Resonance of the Heart

From the teaching, installation, and performance applications, the system proved to be easy to use and reliable to implement. The audio-visual system produced predictable results every time. The tracking system worked well when the users moved their hands slowly and when the users were more concentrative and single-mindedly focused on what they were doing. This concentration and single-minded attention aligned with the basic requirements of conducting a concentration meditation.

The CCS course provided evidence of our creative development of instructional materials utilizing computer-based multi-medias, and technology-mediated audio-visual interface to enhance student learning in electronic music composition and theory. The exit survey of the course indicated that 10 out of 13 students enjoyed their Embodied Sonic Meditation experience. While the results seemed promising, further empirical studies with a bigger subject pool should be conducted in future teaching before we can draw a concrete conclusion.

The art installation at the California NanoSystems Institute provided evidence of the success of our system design to meet a broader users’ satisfaction. From our observation, using real-time body movement to control and modify sonic and graphical properties helps laypersons and children to experience electronic arts in an intimate and fun way.

The live performance at IEEE VIS 2018 provided evidence of strong theatricality when using this system; it also showed the added expressive possibilities that this system provides to the performer. The mapping relationship between the performer’s dramatic gestures and the musical expression were transparent to the audience.

3.4. Embodied Sonic Meditation and Evaluation

For this empirical experiment, 50 viewers reported higher engagement and preference for the original versions, though the level of perceived expression only significantly differed in Experiment 1. In comparison to Experiment 1, Experiment 2 emerged as a more frequently-reported factor in a video being a favorite, rather than the intuitive nature of the matching of the gestures and processing. The “straw man” non-synchronous mapping is a situation where the movement does not affect the sound processing. It (not surprisingly) was proved to be less favored by audience members.

One phenomenon is that, on nine occasions, participants gave a reason to pick an altered version as a preferred performance. While I cannot know for certain to what extent the processing influenced selecting a favorite out of the six performances, each mentioned how expressive the performer was. We might imagine that, in these instances, the expressiveness of the performer was more important than the effects of the desynchronized mapping. When participants preferred a performance that they heard in the synchronized condition, they tended to mention the instrument; otherwise, audiences attributed the expressiveness solely to the performer.

Meanwhile, one song seemed to stand out as participants’ favorite, especially in the synchronized version. The vocalist went into particularly high ranges and sang through several different octaves, and participants stated such things as “the different octaves presented interesting ways for the instrument to manipulate sound,” and “the way it elongated the impressive high notes was what I enjoyed the most.” This again highlights the perhaps complex relationship between how the instrument can accentuate the expressiveness of the performance, provided the performance is already detected to be expressive.

Additionally notable is how few respondents mentioned how the instrument did not distract from the performance. This methodology proved to be effective to be used as a research framework in future DMI evaluation, both in design and mapping strategies, from bodily action to sound perception.

Last but not least, in the mapping experiment, the single “non-intuitive” mapping for comparison was subjectively chosen in my own way. The results showed that this was more frequently not preferred to the original. However, if I had chosen a different mapping (from among infinitely many possible mappings) to compare, the results might be different. While a valid concern, testing more than one “non-intuitive” mapping was out of the scope of this study.

4. Discussion

In the introduction section, I demonstrated the motivation of my art–science collaborations and artistic practice, my cultural background and why I am passionate about Tibetan cultural arts, and intergrade it into my artistic practice. Through the three case studies, I demonstrated my compositional structure, DMI design, and technology implementation of these case studies. I simulated and choreographed the Tibetan Sand-Mandala vocal, dance, and instrumental composition. I activated, with the performer’s arms, 4.5 million particles using a physical computing and motion-tracking system. I combined two sacred instruments into one novel DMI, using state-of-the-art technology in physical computing, simulation, and human–computer interaction, rooted in the soul of ancient Eastern philosophy and Tibetan cultural arts. I aesthetically explored the ancient Tibetan Buddhist philosophy of impermanence, connotation of life cyclic, and non-verbal communication to achieve the goal of promoting Tibetan cultural arts to the general Western audience.

The realization of these case studies greatly benefitted from my collaborators from the computer science and mathematics fields. I strive to define the artistic pursue, search for the appropriate applications of those scientific methods, and then apply them in my art in an innovative way. For example, for the Mandala piece, the original Chai3D framework and the Workspace scaling method were designed for scientific haptic application. Applying them to this specific multimedia piece was an innovative approach. For another example, the mathematical equations that my collaborator Dr. Donghao Ren developed and derived from the original fractal mathematical expression were very sophisticated. However, there is little meaning of these equations until we can pick the most esthetically appealing ones and define those new mathematical mutations and apply them into art forms. These examples are aligned with Hamming’s statement of real engineering and scientific innovation creating impact and meaning to human lives; a concept which I introduced earlier in this article.

Furthermore, from these case studies, I also discovered that sometimes even a cutting-edge technology may not achieve the original goal that an artist planned. For example, due to the difficultness of tracking subtle hand/finger movements using an unreliable sensor, the machine learning algorithm that we developed treats the overlapping Mudra gestures as a classification problem and the best performing model was k-nearest neighbors with 62% accuracy. This is sufficient as a scientific experiment but not enough in the real artistic practice. I have found that people’s embodied sonic mediation experience was often disrupted when the Mudra gestures that they formed were not recognized properly and they described that the “flow” of their body–mind movement were ceased abruptly when what they expected from the system was not happening. For another example, in my evaluation of the TSPW, quite a few users stated that there was no correlation between the DMI design and the expressiveness of a human performer. The performer processes his/her own expressiveness and have the most impact on the audience, while the DMI and performing art technology can only augment this approach. In other words, if the human performer is not expressive or cannot move the audience in a deeper level, no matter how well the DMI was designed, the outcome of the performance will not be promising. I think these findings are fascinating as they provide insights of where technology should be in its place and how we as posthumans should excises our human agency.

Overall, people’s experiences of engaging with all the three systems in the case studies were positive when they generated and effected sounds and visuals by using their own body movement. The usability, reliability, and playability of our systems for both professional music performers and a broader group of users were high. Although further scientific investigation needs to be done, the original goal of creating a direct Embodied Sonic Meditation experience for a broader group of users was realized.

5. Conclusions

Throughout this series of art–science collaborations and scientific investigation, I demonstrated how music, art, science, culture, spirituality, tradition, and media technology can connect people, especially when used with a clear and conscious intent of building cross-cultural exchanges. Our work also showed that media arts have the potential to open new windows onto underrepresented cultural groups, such as Tibetan people. During this six-year collaboration with researchers in both Humanities, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math), and Social Science field from different cultural, ethnic, and racial backgrounds, I discovered that the crucial key that leads to the success of these interdisciplinary collaborations is to be open-minded, humble, grateful, and accountable. This way, mutual trust and respect can be cultivated effortlessly.

Through contemplative practice and art–science research, my collaborators, my students, and I become more connected with ourselves, rippling out with a larger intent to connect in an open way to others, bridging cultural divides, arts, and science. It is my goal that our work can not only provide a new path and method to preserve and promote the Tibetan contemplative heritage with emerging technologies but also projects the marginalized Tibetan cultural values into the cutting-edge art and technology context of contemporary society. Overall, this practice-based research leads to the emergence of entirely new fields of interdisciplinary scholarship and artistic creation, resulting in significant changes on how concepts are formulated in disciplines of the humanities, where art, science, humanity, and technology are integrated, researched, and served as a whole.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2414-4088/3/2/35/s1, A video of the Mandala’s premier can be viewed at: (http://tinyurl.com/ku5cg4f). A fix-media Virtual Mandala film can be viewed at: (https://goo.gl/5TgjJF). A link to the “Imagining the Universe“ concert can be reviewed at https://youtu.be/OaBNyAgiQP8.

Funding

This research was funded by University of California, CCRMA, and Stanford Arts Institute.

Acknowledgments

I thank Curtis Roads, Clarence Barlow, Chris Chafe, Paulo Chagas, and Matt Wright for their mentorship and support. Thanks to Audio Engineering Society, University of California, CCRMA, Stanford Arts Institute, and National Academy of Sciences Sackler Fellowship for their fellowship and funding support. My sincere thanks to all my brilliant research collaborators, especially thanks to Dr. Francois Conti, Dr. Donghao Ren, Yoo Yoo Yeh, and Tibetan musician Cairen Dan. My heartfelt gratitude to all my Tibetan Buddhist teachers and friends who have inspired me greatly during my life.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Stein, R.A. Tibetan Civilization; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T. Mandala Constructing Peace Through Art. Art Educ. 2002, 55, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.; Stevens, K.N.; Tomlinson, R.S. On an Unusual Mode of Chanting by Certain Tibetan Lamas. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1967, 41, 1262–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.M. An Introduction to Buddhism for the Cognitive-Behavioral Therapist. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2003, 9, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marom, M.K. Spiritual Moments in Music Therapy: A Qualitative Study of the Music Therapist’s Experience. Qual. Inq. Music Ther. 2004, 1, 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. Neurophenomenology and Contemplative Experience. In The Oxford Handbook of Science and Religion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, P. The Myth of Shangri-La: Tibet, Travel Writing, and the Western Creation of a Sacred Landscape; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dodin, T.; Heinz, R. (Eds.) Imagining Tibet: Perceptions, Projections, and Fantasies; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, D.S., Jr. Prisoners of Shangrila: Tibetan Buddhism and the West; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, D.; Kenneth, G. Musicology: The Key Concepts; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, N. The Sonic Self: Musical Subjectivity and Signification; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.D. Music, Language, and the Brain; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems; Mifflin: Houghton, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, J. Affordances and the Musically Extended Mind. Front. Psychol. 2014, 4, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roads, C. Composing Electronic Music: A New Aesthetic; Oxford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas, P.C. Unsayable Music: Six Essays on Music Semiotics, Electroacoustic and Digital Music; Leuven University Press: Leuven, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, S. Music, Meaning and Transformation: Meaningful Music Making for Life; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, L.A.; Gelman, S.A. (Eds.) Mapping the Mind: Domain Specificity in Cognition and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, L.B. Emotion and Meaning in Music; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wanderley, M.M.; Orio, N. Evaluation of Input Devices for Musical Expression: Borrowing Tools from HCI. Comput. Music J. 2002, 26, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leman, M. Embodied Music Cognition and Mediation Technology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hamming, R.R. Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, B. The Wheel of Time Sand Mandala: Visual Scripture of Tibetan Buddhism; Snow Lion Publications: Boulder, CO, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.C. The Expressionist: A Gestural Mapping Instrument for Voice and Multimedia Enrichment. Int. J. New Media Technol. Arts 2015, 10, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.C.; François, C. The Virtual Mandala. In Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F. The CHAI Libraries; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Khatib, O. Spanning large workspaces using small haptic devices. In Proceedings of the First Joint Eurohaptics Conference and Symposium on Haptic Interfaces for Virtual Environment and Teleoperator Systems, Pisa, Italy, 18–20 March 2005; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sopa, G.L. The Wheel of Time: Kalachakra in Context; Shambhala: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Khenpo Sodargye’s Talks. Available online: http://www.khenposodargye.org/ (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- JackTrip Documentation. Available online: https://ccrma.stanford.edu/groups/soundwire/software/jacktrip/ (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- Chafe, C.; Gurevich, M. Network Time Delay and Ensemble Accuracy: Effects of Latency, Asymmetry. In Audio Engineering Society Convention 117; Audio Engineering Society: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.C.; Yeh, Y.H.; Michon, R.; Weitzner, N.; Abel, J.S.; Wright, M. Tibetan Singing Prayer Wheel: A Hybrid Musical-spiritual instrument Using Gestural Control. In Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME), Brisbane, Australia, 11–15 July 2016; pp. 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hayles, N.K. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M. Speciation, Transvergence Allogenesis Notes on the Production of the Alien. Archit. Des. 2002, 72, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.C.; Smith, J.O.; Zhou, Y.; Wright, M. Embodied Sonic Meditation and its Proof-of-Concept: Resonance of the Heart. In Proceedings of the 43rd International Computer Music Conference, Shanghai, China, 17 October 2017; pp. 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Philosophy in the Flesh; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveros, P. Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice; IUniverse: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- O’modhrain, S. A Framework for the Evaluation of Digital Musical Instruments. Comput. Music J. 2011, 35, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.C.; Huberth, M.; Yeh, Y.H.; Wright, M. Evaluating the Audience’s Perception of Real-time Gestural Control and Mapping Mechanisms in Electroacoustic Vocal Performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME), Brisbane, Australia, 11–15 July 2016; pp. 206–211. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).