6.1. Test Population Data Statistics

This study adopted an experimental research method, primarily targeting undergraduate and graduate students at universities. As shown in (

Table 5) 59 participants (Male = 34) were selected among students with prior experience using digital devices to ensure basic operational proficiency. Testing was conducted in five groups: 10% Freshmen, 24% Sophomores, 34% Juniors, 14% Seniors, and 19% Graduate Students. Each group completed the MR game testing sequentially, followed by a post-experiment questionnaire.

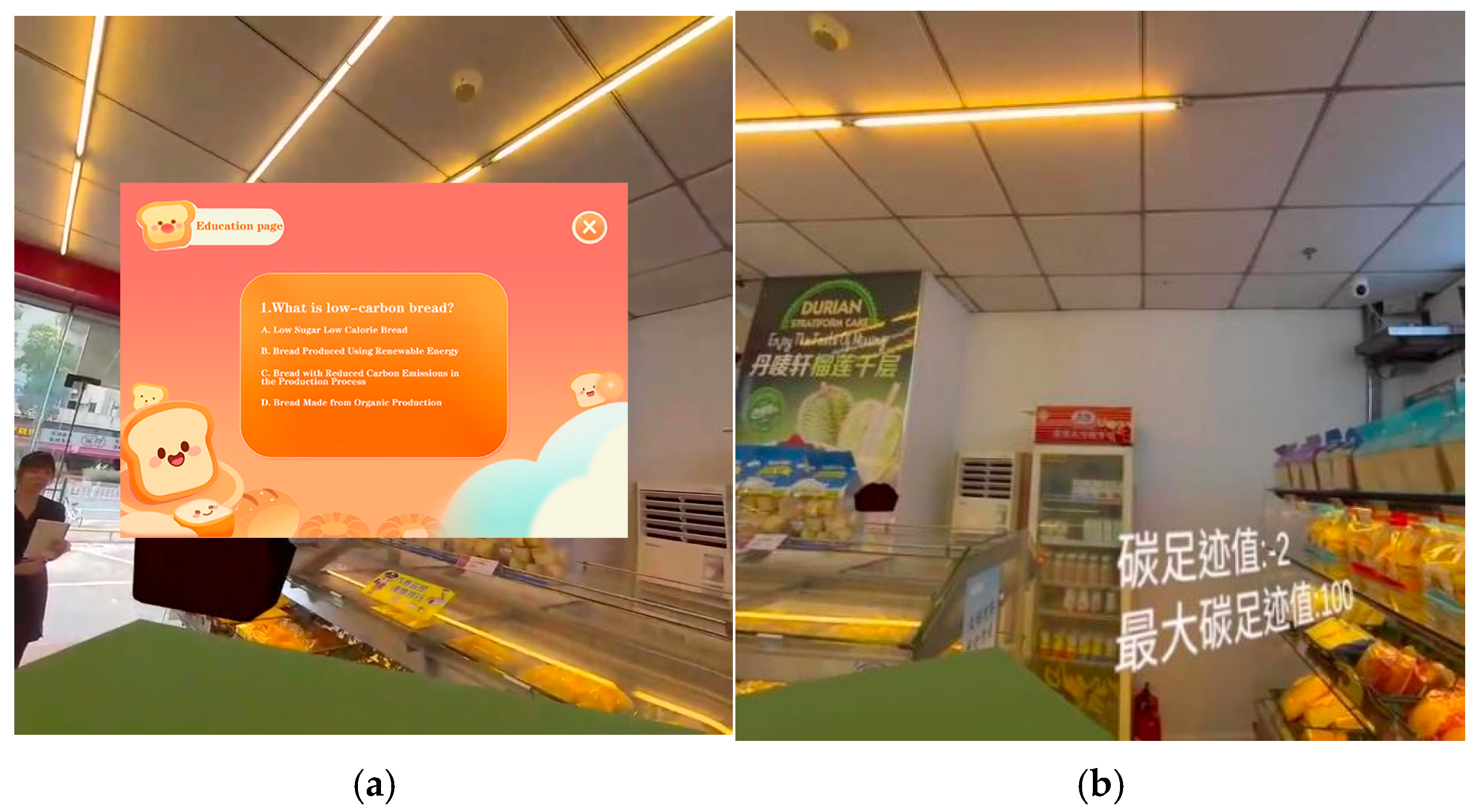

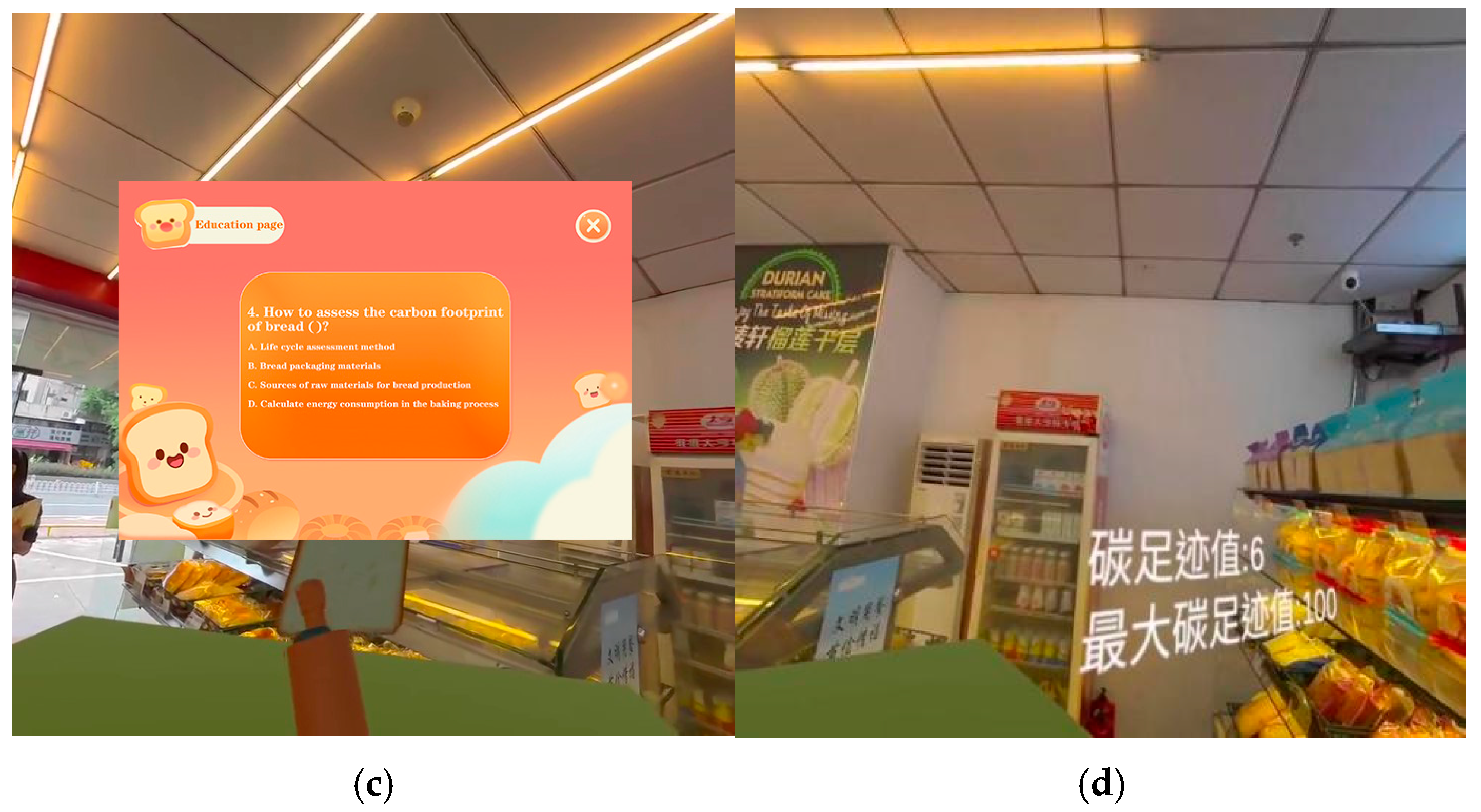

During the experimental process, participants were required to complete the MR game testing experience in sequence. Among these, 15 students had neither previously used VR devices nor engaged in interactive games like ‘Leftover Food’. Each participants wore VR equipment (

Figure 6) to engage with the game and complete corresponding levels. During formal testing, participants entered the game after viewing the instructions interface. Upon completing the game, participants undertook carbon footprint learning assessments.

With participants’ informed consent, the testing process was documented through photography and other appropriate means. Following the collection of questionnaires, the feasibility and validity of the sample were verified. The core scale used in the original version demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α > 0.7. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) revealed excellent model fit indices (CFI > 0.9, RMSEA < 0.08), and factor loadings generally exceeded 0.6, confirming the validity of the scale.

6.2. Questionnaire Reliability and Validity Analysis

This section presents the results of reliability and validity testing conducted on the questionnaire following data collection. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, a measure of internal consistency ranging from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate greater reliability.

The IBM SPSS Statistics 27 reliability analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.839, indicating good reliability for the questionnaire. This suggests a high degree of internal consistency among the scale’s items and satisfactory validity for evaluating factors related to MR interactive game experiences (

Table 6).

In addition, this study employed SPSS software to conduct the KMO measure and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. The KMO value is 0.839, and Bartlett’s test produced a statistically significant result of p < 0.001, demonstrating sufficient inter-variable correlation and confirming the validity of the data for factor analysis.

Table 7 shows that the overall experience exhibits highly positive engagement and extremely low negative emotions, with variations within the positive dimensions. Specifically, across the five dimensions representing positive experiences, participant feedback clustered predominantly at moderately high levels. The mean scores for Competence (M = 2.58) and Flow State (M = 2.58) tied as the highest, with concentrated distributions (SD = 0.786 and 0.829, respectively). Notably, 26 participants (43.42%) rated Competence at the highest level 3, while 24 participants (40.7%) did the same for Flow State. This strongly suggests the experience successfully enabled participants to perceive their competence matching task demands while entering a state of deep focus and enjoyment, aligning with the ideal data observed during the initial hypothesis testing. Closely related metrics—sensory immersion (M = 2.47) and positive affect (M = 2.50)—also remained at similarly high levels. Level 2 ratings were given by 25 participants (42.95%) for sensory immersion and 24 participants (40.7%) for positive affect, indicating that most individuals experienced emotional pleasure and imaginative immersion alongside cognitive engagement in the educational activity. Although the challenge dimension had a relatively balanced mean score (M = 2.50), it exhibited the largest standard deviation (SD = 0.841), indicating more pronounced individual differences in perception. This likely reflects the task design allowing participants of varying skill levels to identify their own difficulty points: some found it just right (24 participants, 40.02%), while others perceived it as more demanding (7 participants, 11.88%).

In contrast to these positive dimensions, the two negative dimensions—Anxiety/Worry (M = 0.31) and Negative Emotion (M = 0.31) exhibited extremely low average scores with distributions heavily clustered at the lower end. A substantial majority of participants (44 participants, 74.6%, and 46 participants, 77.58%) reported experiencing no anxiety or negative emotions whatsoever, with only a very small minority expressing mild negative feelings. Collectively, the data reveal an efficient and healthy experiential structure: driven by moderate challenge, it robustly supports a widespread sense of competence and flow experiences, generating intense immersion and positive emotions while keeping negative emotions at extremely low levels.

Following testing sessions, several students shared their reflections. Four participants were randomly selected from the 59 respondents for qualitative interviews (P-15, P-16, P-19, P-25):

P-15: “I’ve seen similar videos before, but trying it myself for the first time was still quite interesting.”

P-16: “I felt a real sense of accomplishment seeing my score after finishing the game.”

This study was intentionally designed to present game content in the most intuitive and accessible way—using simple gestures such as striking bread with a rolling pin—to foster embodied interaction and real-world engagement. Over 98% of students reported successful interaction with the MR environment and expressed willingness to replay the game to achieve higher scores.

Nevertheless, for many students unfamiliar with VR equipment, the first experience remains somewhat unfamiliar or intimidating.

P-19: “I was a bit nervous, but it’s quite novel.”

P-25: “It’s challenging the first time, but it gets easier with practice.”

Regarding the challenge dimension, 95% of participants reported that this was their first hands-on exposure to VR. Although most had played similar web-based games or watched VR gameplay videos, the direct experience initially posed challenges. However, after brief guidance and training, over 90% of students found the system easy to use and reported no significant difficulties.

6.3. Overall Analysis and Evaluation of Game Testing

The System Usability Scale (SUS) tool was used to systematically evaluate system usability from the end-user perspective. In industrial usability research, SUS accounts for 43% of post-study questionnaire usage (

Table 7). This instrument consists of 10 statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from which weighted average percentages are calculated.

This study was conducted with two participant groups with prior VR or AR experience and those without. The group criterion was based on quantitative Question 3: “Have you ever used VR equipment or played augmented reality games?” Participants reporting 0–1 instances of use were classified as the non-user group, while those reporting 2–3 instances were assigned to the user group (acknowledging that some may have used either VR or AR games, but not both). Due to the scale of the test, 20 participants were selected for grouped testing. The non-user comprised 9 males and 6 females (average age 20.5), distributed across sophomore and junior years. The user group included 10 males and 5 females. Each group was further subdivided into participants with and without operational experience. All participants completed the SUS questionnaire before date analysis.

The SUS questionnaires and corresponding statistical data for each item in the non-user group were analyzed. The overall average converted score was 72.8 points (range 70–85), which exceeds the SUS benchmark average of 68 points, indicating good overall system usability. However, significant internal variation was observed across different items.

To facilitate comparison, the results were categorized into high, medium, and low scoring groups. High-scoring group: Items A5 (85 points) and A4 (77.5 points) performed exceptionally well, far exceeding the excellent threshold (80 points), reflecting mature and well-developed interaction design. Medium-scoring group: Items A1 (72.5) and B1 (72.5) were close to the overall mean, indicating a standard level of usability. Low-scoring group: Items A7, B2, B3 (all 70 points) slightly exceeded the baseline but still showed clear potential for improvement.

Summary: For Item Q4 (Technical Dependency), the mean score was 2.8 (SD = 0.7). The low-scoring items (e.g., A7, B3) received scores ≤ 2, showing notable contrast from the high-scoring item (A5 = 4). This result reflects a stratified distribution of user technical proficiency, suggesting that beginners require additional guidance and support during interaction.

According to SUS metrics

Table 8 and

Table 9, both user group and the non-user group scored above 70—significantly exceeding the benchmark average of 68. This indicates the system’s high usability and positive user engagement. The MR game effectively encouraged emotional involvement, increased interactivity, and generated strong with layout and design. Nevertheless, several participants suggested that the game’s motivation could be further enhanced. Future versions will consider incorporating leaderboards, reward badges, or similar gamification features to promote user engagement and a sense of accomplishment. A few users also mentioned initial operational difficulty during their attempt, reinforcing the need for improved tutorial design.