Increasing Usability of Homecare Applications for Older Adults: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. State-of-the-Art in Homecare

- Communication and social contact: A number of platforms include communication functionalities, such as videoconferencing, email or chat, allowing seniors to remain in contact with their families and peers. Social networking features, such as newsfeeds and multimedia galleries, enable them to keep up with community events and stay connected with their loved ones by sharing content, such as photos and videos. This type of services promotes social engagement, which can help seniors who live in isolation and may be struggling with loneliness, boredom and depression. Also, such features facilitate the creation of a supportive network of caregivers. Examples of commercial systems offering this type of service are “Claris Companion” [17], “EnGage Pad” [18] and “Gociety” [19].

- Health monitoring: Several homecare solutions incorporate medical devices, such as pulse oximeters or blood pressure monitors, as well as other devices that measure various parameters within the home environment (e.g., cameras or physical activity trackers), to capture real-time information about the user’s physical and physiological status. The data can be stored in cloud infrastructure so that it is available to healthcare professionals, who can evaluate the information and create customized care plans, while anomalies or deviations from normal user-adjusted patterns can be automatically detected. Some well-known commercial platforms that provide health monitoring features are “BePatient” [20] and “SilverVue” [21].

- Emergency management: Other systems focus primarily on emergency response, with features such as “red button” service, smart home sensors (e.g., smoke detectors), activity tracking through wearables and cameras, location tracking and geofencing, to identify various types of potentially dangerous situations and automatically route the required support. Examples of such systems are “BeClose” [22] and “Care@Home” [23].

2.2. Usability Assessment Methodologies

- Inspection methods: This type of method involves observation of users by an expert. Popular methods of this type are ethnography, heuristic evaluation and pluralistic inspection. Users are usually not involved directly.

- Inquiry methods: In this approach, qualitative data is collected from users of the system. Examples of this category are focus groups, surveys and interviews.

- Testing methods: This approach refers to the collection of quantitative data from potential users in a realistic environment. Some examples are benchmark testing, remote usability testing and the Think Aloud protocol.

2.3. The “HeartAround” Platform

2.3.1. General Description

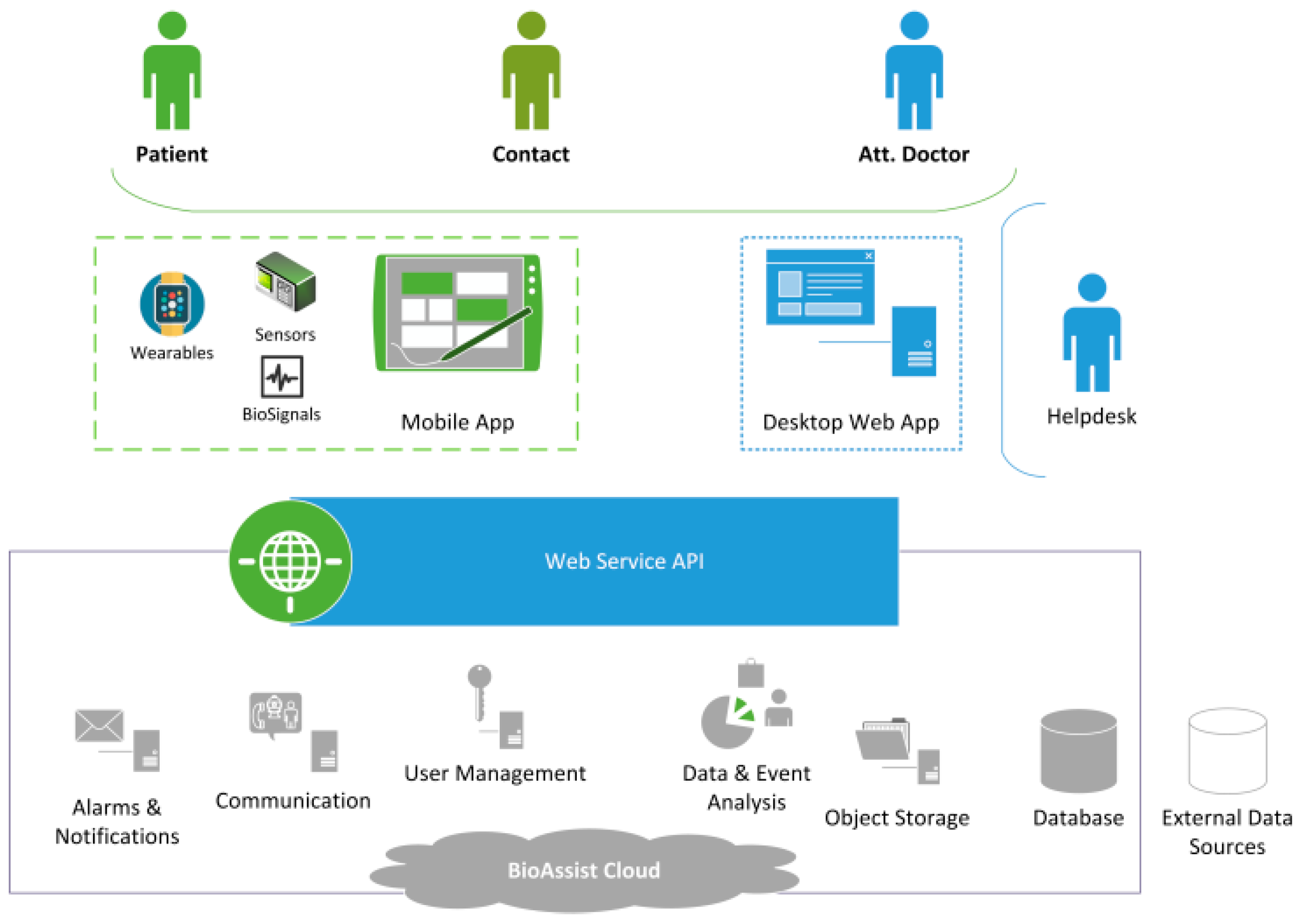

2.3.2. System Overview

2.3.3. Functionalities

- Contact Management and Videoconferencing: Each user is able to manage a list of contacts, which may include friends and family members, as well as their doctors. These contacts form a circle of caregivers, who can access the system from their own devices and communicate with the senior, as well as receive valuable information about the senior’s well-being and notification in case of need. The contact list can also be managed remotely by a caregiver or the helpdesk. Contacts are displayed in the “Contacts” screen with their name and profile photo. The user may initiate a video call to a contact with a single touch. Contacts that are available for videoconferencing are grouped at the top of the list, as can be seen in Figure 3a.

- Reminders: Reminders can be set, either by a caregiver or by the user, for health-related tasks, such as doctor appointments, or daily activities and social engagements. Reminders for medications and measurements are created automatically. The user receives a reminder notification on the tablet (Figure 3b). In case the user skips a medication reminder, a caregiver is automatically notified, in order to ensure adherence to the treatment.

- PHR and Biosignals: The platform incorporates an integrated, cloud-based personal health record, which includes demographics, medical history, medication, allergies, laboratory test results and personal statistics, such as age and weight. Patients are able to view and add content to their personal record via the mobile application. Users can also utilize compatible wireless sensors to monitor and record their biosignals and physical activity. New measurements are stored automatically in their personal record. The user can view past measurements at any time on their tablet, in the form of a graph. An example is shown in Figure 3c. Users can grant their doctors access to their personal health record. Doctors can view and update their patients’ records through the doctor’s web inter-face (Figure 3d), manage prescribed medications, set the daily schedule of biosignal measurements and patient-specific thresholds for each type of measurement, create reminders and receive reports on their patient’s status.

- Gallery: End-users are able to view photos and videos uploaded by their contacts. They may also upload content of their own. Whenever one of the user’s contacts uploads a new photo or video, the user receives a notification. While the application remains idle, the device acts as a digital frame, displaying all of the user’s and their contacts’ photos in a slideshow. The user can also manage which photos are displayed in the slideshow.

- Emergency Call: In case of emergency, the end-user can receive assistance and medical advice from the service’s helpdesk, with the touch of a single button.

2.3.4. Applied Guidelines for Usability

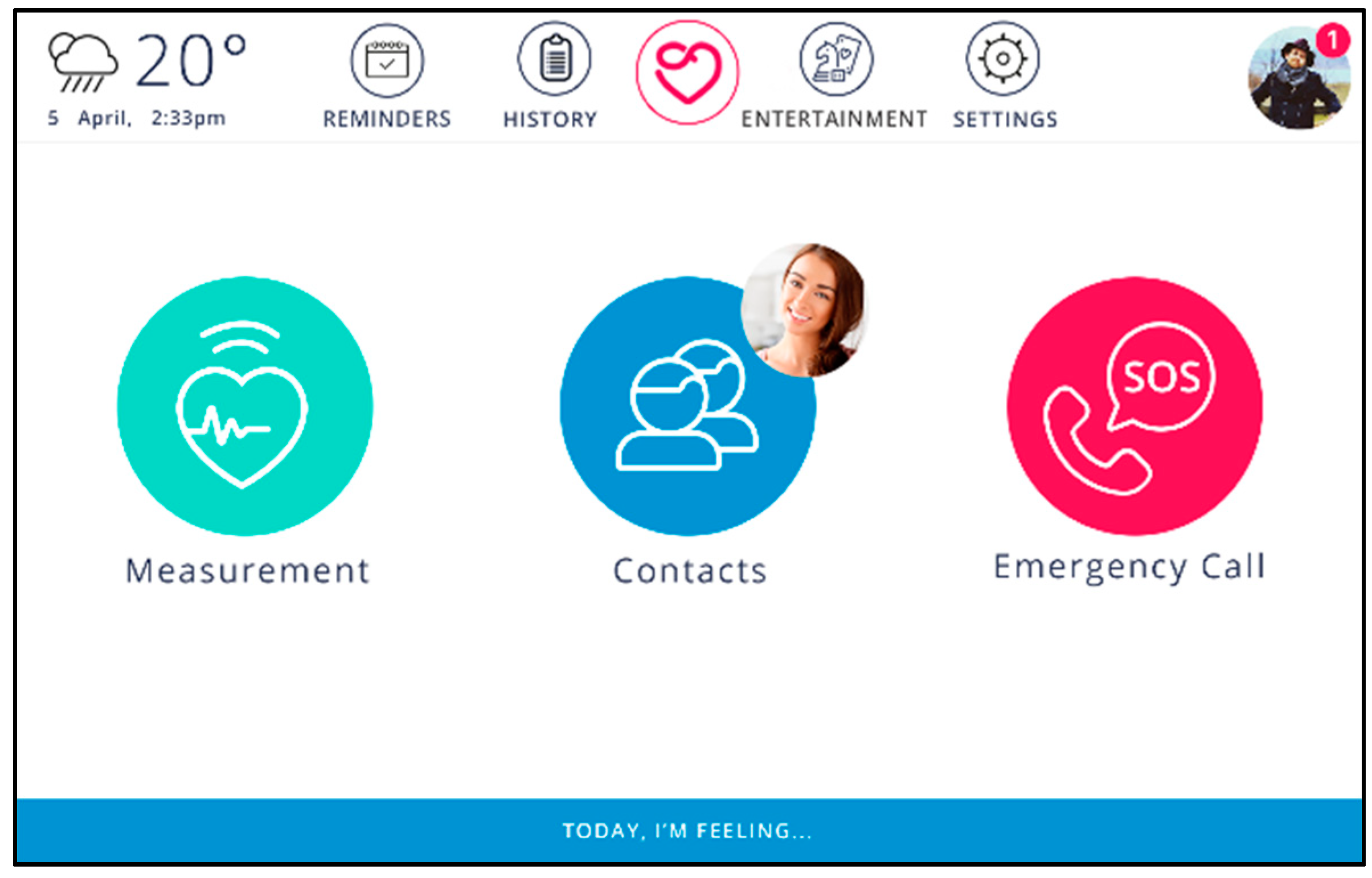

- User Interface: The mobile application user interface was designed in alignment with well-established usability requirements for elderly people and people with sensory impairments. Large buttons, icons and fonts have been used to maximize readability. The colors that were used were chosen so as not to distract users’ interaction with the system, taking into consideration seniors’ poor color and contrast sensitivity. More than ensuring visual accessibility, colors were used in an appropriate way according to their common interpretations (e.g., green is usually interpreted as positive).

- Devices: Seniors must be able to interact with the system as naturally as possible, so the choice of device is crucial. Different people express different preferences, which can greatly affect a user’s level of comfort with a system, with seniors usually opting for devices they are already familiar with. The mobile application is capable of adapting to the user’s preference, with a responsive design that can run on various devices, including smartphones and tablets, but also on TVs. Considering that many seniors experience difficulties in using the keyboard or the mouse, especially those suffering from tremors of Parkinson’s, the system focuses mainly on touch screen devices.

- Multimodality: The use of multiple modalities is required to address the needs of people with sensory impairments, as the acuity of sensory modalities declines with age [13,14], especially in the case of chronic patients. For example, diabetes may lead to impaired vision, while the number of people with both vision and hearing impairment is increasing. This highlights the importance of alerts based on touch. For this reason, the system presents notifications and reminders with sound and visual alerts on the tablet, as well as vibration alerts on the smartwatch. Concurrent use of multiple modalities ensures maximum effectiveness.

- Understandability: The majority of seniors perceive mobile applications as computer-based systems, which can cause them anxiety or fear. The user interface contains few buttons, to address this problem. For simplified navigation, nested menus were avoided, ensuring that the application is easy to understand. Moreover, important information is always presented with icons, rather than text alone, to aid users to understand quickly what they need to do next.

- Automation: In order to minimize the level of action required from the end-user, several tasks can be executed automatically (e.g., creation of reminders, auto-answer for video calls). In addition, tasks may be assigned to caregivers (e.g., creation of measurement schedule, contact list management). This ensures simplicity of use and decreases the potential of fatigue or boredom when using the application. In addition, the application incorporates mechanisms for automatic connection with devices, which greatly simplifies data entry, as well as mechanisms for automated recovery in case of faults, including automatic reconnection with the service and automatic relaunch of the application.

- Motivation: In order to motivate end-users to engage with the system, enjoyable features, such as the gallery functionality, are a key addition. Content sharing between end-users and their families is also important for promoting social engagement. Furthermore, the application’s visualization capabilities allow users to view a day-to-day graphical representation of their health status, providing an important communication tool between patients and doctors and a sense of empowerment to the users.

3. Usability Evaluation

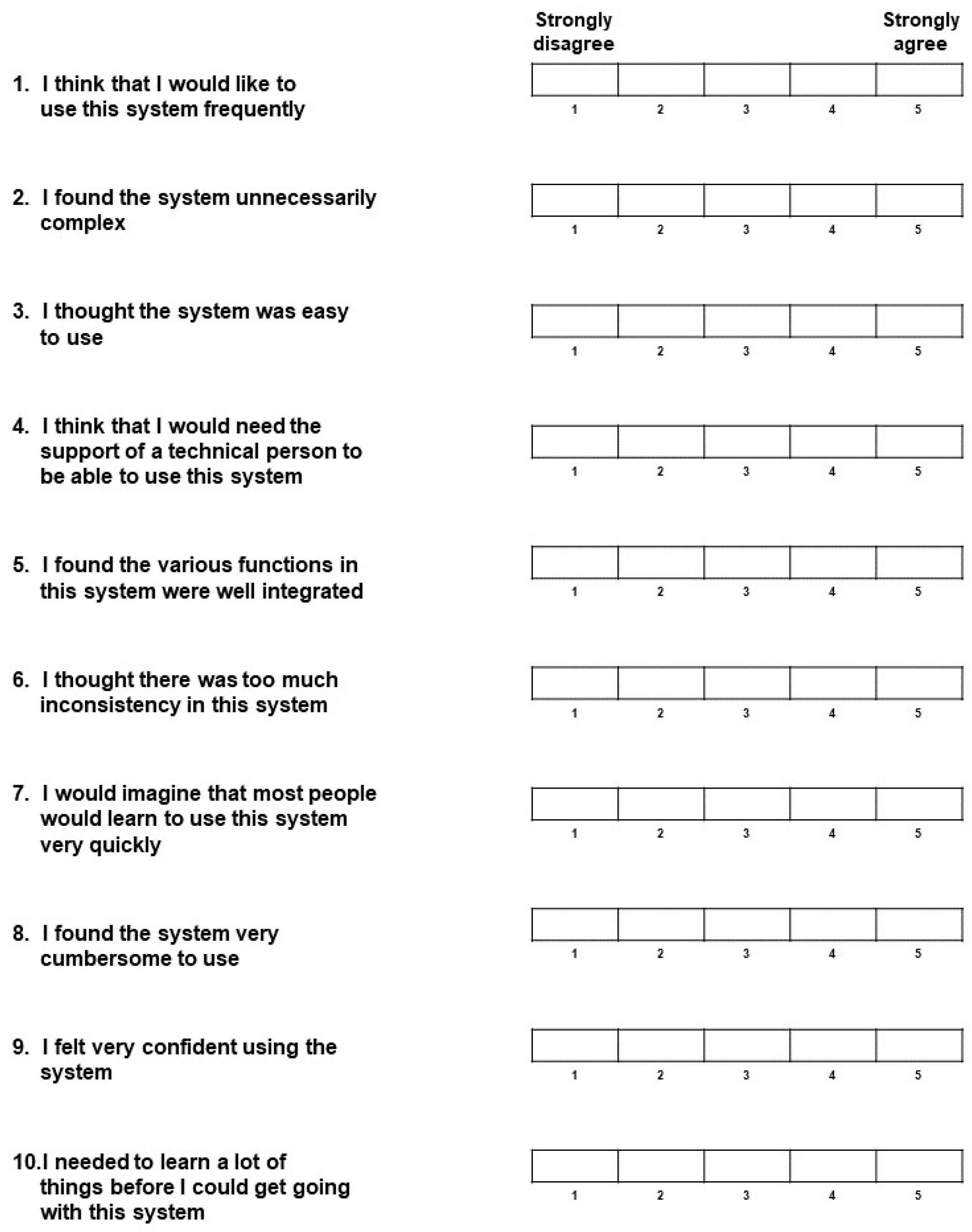

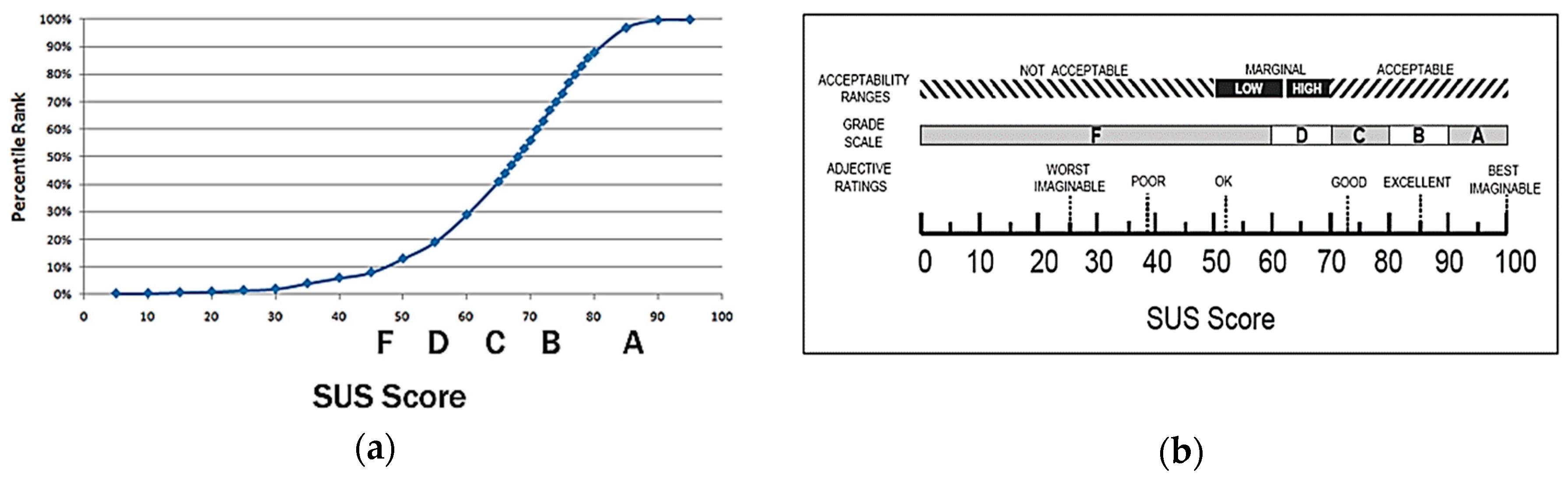

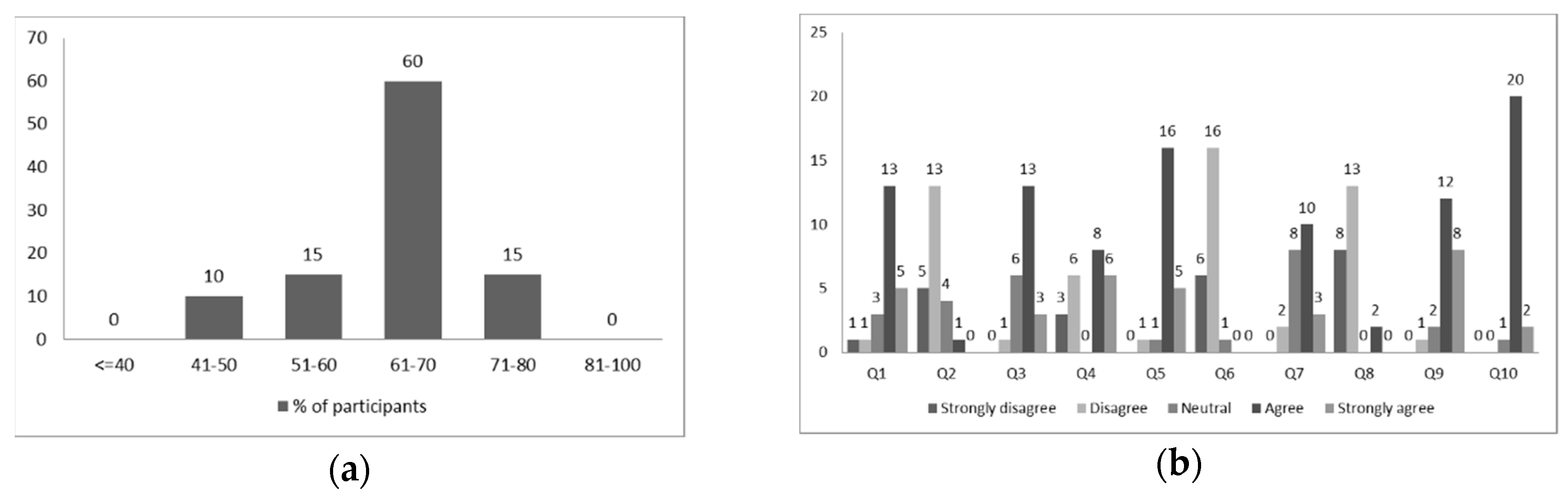

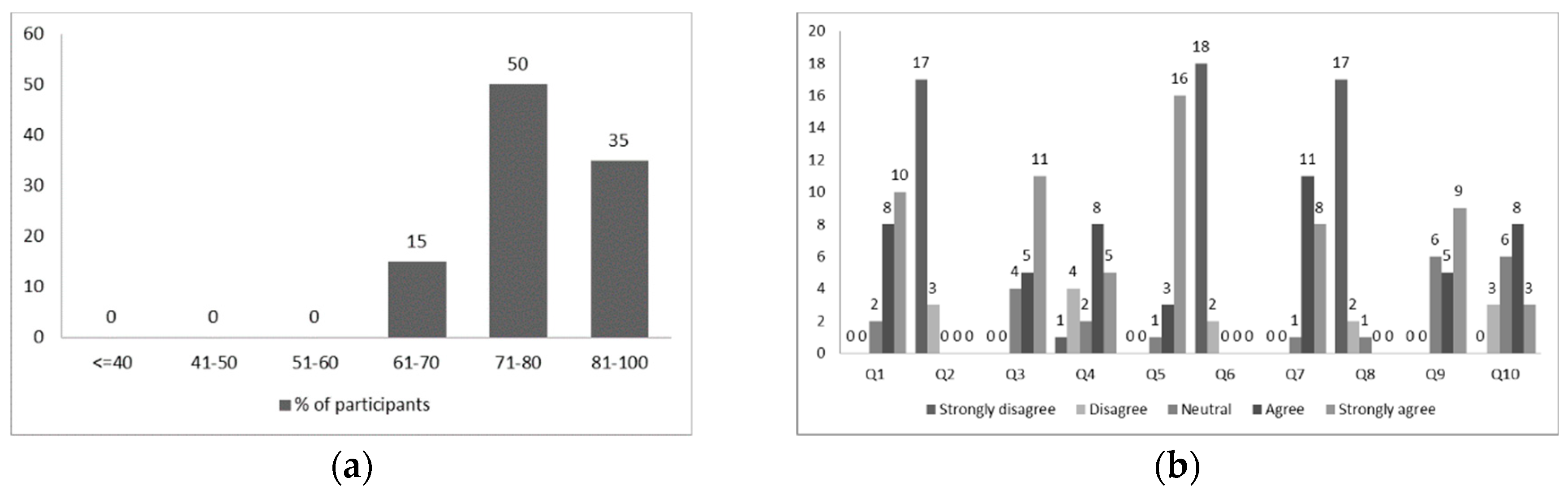

3.1. Initial Evaluation with SUS

3.1.1. Setup and Methodology

3.1.2. Results

3.2. Qualitative Assessment

3.2.1. Setup and Methodology

- The discussions started with personal questions, to gain some information about the participant’s background, daily life and needs and build a personal and health profile based on their answers.

- The next section of the interview contained some general questions to examine the participants’ attitude and experiences with regard to technology, and to identify potential physical and psychological issues that may hinder them when using computers and ICT systems, focusing on subjects such as thoughts and emotions when interacting with technology and the availability of support from their environment.

- The interview continued with an introduction to the concept of homecare and telecare systems, which was new to most of the participants, and a brief description of the platform. They were then asked to express their thoughts on the idea and try to imagine and describe how they visualize the system.

- A detailed presentation of the system followed, explaining the various devices, the platform’s capabilities and features, and communication between the various stakeholders. The respondents were given the opportunity to interact with the mobile application if they wanted and where asked to provide general feedback, ask questions and compare the actual system with their expectations.

- An important part of the discussion was dedicated to the application’s graphical user interface (GUI). The participants were asked to provide feedback on the visual accessibility, understandability and aesthetic appeal and express thoughts and emotions. They were also asked to provide suggestions for improvements.

- A much more detailed explanation of the various functionalities of the application followed. Participants were asked to comment on the usefulness and usability of each feature, how well integrated they found the various components to be and how easy it was for them to understand each feature. They were also asked how often they thought they would use each feature and how important each feature is to them, as well as to give suggestions of new features that would be of value or appeal to them or to other potential users of the platform. Finally, they were asked to compare certain functionalities of the application to other solutions they may be using the same purpose, with respect to effectiveness, usability and reliability and indicate which solution they found more pleasant. For example, the videoconferencing feature was compared to other means of communication, such as the telephone, email and Skype.

- Devices and interaction with the system were also an important topic of discussion, in an attempt to explore physical limitations, but most importantly psychological barriers and ways to overcome them. Participants were asked to comment on the choice of the tablet as the main device of the system, describe their attitude and feelings towards mobile devices and touch screens and compare their preference between various devices (e.g., PCs, smartphones, TVs, etc.) and means of interaction with the system (e.g., keyboard, remote control, etc.). They were also encouraged to think outside of the box and suggest other devices that they could think of as noteworthy options.

- In this part of the discussion, the moderator informed the participants of the various mechanisms for automation that are incorporated in the system. The participants were asked to express their views on the subject and explain how this information affects their attitude towards the system.

- At the end of the discussion, the participants were given the opportunity to add any comments that they may have skipped and provide general feedback, ideas and suggestions.

3.2.2. Findings and Insights

- User Interface Design: Participants described the user interface as “simple”, “not confusing” or “less complicated than they expected”, especially in comparison to other systems, with all of them giving positive general feedback, and commending the limited number of options featured on the home screen. Positive responses were also given on the size of home screen elements, which contains large buttons that can be viewed comfortably, as well as the icons used, which almost eliminate the need to read text on the screen, while also helping them make associations with the respective functionalities and therefore navigate the application more easily. Some also commented positively on the use of color. One participant expressed the need for brighter and highly contrasting colors. However, this was mostly a recommendation for aesthetic appeal, as they mentioned that the current color scheme was also easy to view. Another participant mentioned that they noticed and appreciated the meaningful use of color (i.e., green colored confirmation buttons, red colored emergency and delete buttons, etc.), explaining that knowing right away which buttons they should be careful before pressing reduces their fear of making a mistake when using the system. Finally, some respondents mentioned that they would like to be able to change the font size.

- Devices: Most participants agreed that tablets are an appropriate device for running the end-user application, due to their size, portability and mobility, despite the fact that some of them reported that they have been hesitant to use or purchase one. Although all participants are much more familiar with TVs, some of them found the idea of running the application on a TV confusing, having a hard time imagining how they would operate the system. Furthermore, some mentioned that they associate TVs with a different purpose, and they would prefer to use this system on a separate, dedicated device. None of the respondents faced any difficulty using the sensors, even those who do not use them in their daily lives, mainly because of the automated communication of the sensors with the application. In fact, all participants suffering from chronic conditions thought that this manner of electronic recording of measurements is far more convenient than writing down measurements on paper every day. An important unresolved issue, however, is device control and manual input. Most participants expressed aversion to touch screens, because they fear an increased chance of making mistakes, mainly due to reduced sense of touch. This can also lead to frustration and loss of patience, especially when handling touch screen keyboards. Some further characterized them as intimidating, while others mentioned that they perceive touch screens as too advanced for their generation. Those who had some previous experience with computers would opt for a regular keyboard for typing and were therefore in favor of adding to the system a dock with a small keyboard. Many also responded well to the idea of a remote control initially, but later expressed concerns of confusing it with remote controls of other devices or losing it. All participants either suggested or would agree that the addition of a few simple voice commands would be of great value.

- Functionality: The respondents considered the various system functionalities useful and well integrated. In addition, they appreciated the limited number of steps required to perform even the most complicated tasks they were presented with, such as recording biosignal measurements or creating reminders. Almost all participants expressed their appreciation of the reminders feature. One participant was particularly enthusiastic about the automated functionality of reminders, providing remarks such as “leaves no room for error”, “someone else can do it for me” and “it would be someone else’s responsibility” and explained how manual input of important data can be stressful for him, for fear of making mistakes. The gallery feature was described by many respondents as “enticing” and agreed it would encourage them to engage with the system more. Overall, the features mostly appreciated by the respondents were video calls, reminders and the gallery. Participants believed that these were the functionalities they would use more regularly. A couple mentioned that they found the personal health record functionality very useful, but would probably not use it as frequently as other features and thus would prefer if it was not visible on the home screen. Some respondents expressed desire for a home screen that could be customized to their preference, removing those buttons that they would use less.

- Understandability: Participants found the platform and the various functionalities fairly easy to understand, provided they were given a presentation of the system. However, most of them felt that they would require some training or assistance to use it. A number of participants compared performing tasks on the system to performing tasks on a computer. They felt that the sequences of steps to perform tasks on the system were short enough to remember, although more time would be required for them to gain confidence in using the system. They all agreed that short and simple audio or animated instructions could be a helpful feature, although some of them expressed preference for printed material, such as a user’s manual or a cheat sheet. A significant finding that emerged was that senior users’ need to feel in control of the system. One of the respondents mentioned that it was important for him to know how every feature that was displayed on the screen operates and that since no visible feature was too complicated for him to understand, he felt more confident and appreciated the design. Other respondents commented that they felt calmer and more confident and relaxed when using this system, in comparison to using a computer, because it appeared simple, regardless of how complicated it actually was.

- Motivation to Adopt: Discussion of parameters that affected the respondents’ motivation to adopt homecare technologies was one of the most important parts of the interviews. A number of participants underlined the importance of technology fulfilling a need as motivation for adoption and explained that they would use a homecare system if they felt they needed it, or if they were instructed to do so by a doctor. One respondent further commented that only a major health incident would make her feel the need for health monitoring. However, all of the respondents found very appealing the fact that their doctor would be able to monitor their health status, as well as being able to easily communicate with their caregivers. As one participant commented, “it makes you feel more secure, that someone cares and is in charge”. This indicates the importance of communication features connecting the various stakeholders, in order to increase perceived value. Finally, many of the respondents mentioned that they would be motivated to use technology for entertainment and thus would appreciate features such as multimedia players or games. Besides functionality, it was evident throughout the interviews that ease of use is essential to motivate older adults to adopt new technologies. When the participants were informed of the various mechanisms for automation and remote management incorporated in the system, they all responded with very positive remarks. For most of them, this information greatly changed their attitude towards the system and increased the likelihood that they would adopt it in their daily lives, regardless of the number of features that they would actually feel comfortable using on their own.

3.3. Redesign

3.3.1. Redesigning the GUI

3.3.2. New Features

3.4. Re-Evaluation with SUS

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitzner, T.L.; Boron, J.B.; Fausset, C.B.; Adams, A.E.; Charness, N.; Czaja, S.J.; Dijkstra, K.; Fisk, A.D.; Rogers, W.A.; Sharit, J. Older Adults Talk Technology: Technology Usage and Attitudes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1710–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. The Information Aged: A Qualitative Study of Older Adults’ Use of Information and Communications Technology. J. Aging Stud. 2004, 18, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Chen, Y.; Hewitt, L. Age Differences in Constraints Encountered by Seniors in Their Use of Computers and the Internet. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsis, T.; Demiris, G.; Pedersen, S.; Hartvigsen, G. Home Telecare Technologies for the Elderly. J. Telemed. Telecare 2008, 14, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PACITA Project. EU stakeholder involvement on ageing society. Telecare Technology for An Ageing Society in Europe. Current State and Future Developments. Available online: http://wp6.pacitaproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Telecare-description-web.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Ojel-Jaramillo, J.M.; Canas, J.J. Enhancing the Usability of Telecare Devices. Hum. Technol. Interdiscip. J. Hum. ICT Environ. 2006, 2, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorri, L.; Leinonen, E. Technology That Persuades the Elderly. In Persuasive Technology; Oinas-Kukkonen, H., Hasle, P., Harjumaa, M., Segerståhl, K., Øhrstrøm, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5033, pp. 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, V.L. Influencing Technology Adoption by Older Adults. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, K.; van Biljon, J. Predicting Technology Acceptance and Adoption by the Elderly: A Qualitative Study. In Proceedings of the 2008 Annual Research Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists on IT Research in Developing Countries Riding the Wave of Technology-SAICSIT 08, Wilderness, South Africa, 6–8 October 2008; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.; Hassanein, K.; Head, M. Computer Use by Older Adults: A Multi-Disciplinary Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, S.L.; Tak, S.H. Computer, Internet, and E-Mail Use Among Older Adults: Benefits and Barriers. Educ. Gerontol. 2008, 34, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsoule, E.; Koutsabasis, P. Redesigning Websites for Older Adults: A Case Study. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2014, 33, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, M.; Shawish, A. Taxonomy of Usability Requirements for Ageing. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Software Engineering, Parallel and Distributed Systems-SEPADS ’14, Gdansk, Poland, 15–17 May 2014; pp. 80–88, ISBN 978-960-474-381-0. [Google Scholar]

- McGee-Lennon, M.R.; Wolters, M.K.; Brewster, S. User-Centred Multimodal Reminders for Assistive Living. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems-CHI ’11, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; ACM Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011; p. 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahasanović, A.; Brandtzæg, P.B.; Heim, J.; Lüders, M.; Vermeir, L.; Pierson, J.; Lievens, B.; Vanattenhoven, J.; Jans, G. Co-Creation and User-Generated Content–Elderly People’s User Requirements. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 655–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS—A Quick and Dirty Usability Scale. Available online: http://cui.unige.ch/isi/icle-wiki/_media/ipm:test-suschapt.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Claris Companion Official Website. Available online: http://www.clariscompanion.com (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Engage-Pad Official Website. Available online: http://www.onetouchtelecare.com/index.html (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Gociety Official Website. Available online: http://www.gocietysolutions.com/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- BePatient Official Website. Available online: http://www.bepatient.com/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Silvervue Official Website. Available online: http://www.silvervue.com/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- BeClose Official Website. Available online: http://beclose.com/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Care@Home Official Website. Available online: http://www.essence-grp.com/smart-care/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Genise, P. Usability Evaluation: Methods and Techniques; Version 2.0; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A Retrospective. J. Usability Stud. 2013, 8, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bangor, A.; Kortum, P.; Miller, J. Determining What Individual SUS Scores Mean: Adding an Adjective Rating Scale. J. Usability Stud. 2009, 4, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- WAMMI Official Website. Available online: http://www.wammi.com/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- QUIS Official Website. Available online: http://www.lap.umd.edu/quis/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Dhillon, J.S.; Wünsche, B.C.; Lutteroth, C. An Online Social-Networking Enabled Telehealth System for Seniors: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth Australasian User Interface Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 29 January–1 February 2013; Australian Computer Society, Inc.: Darlinghurst, Australia, 2013; Volume 139, pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Stojmenova, E.; Imperl, B.; Žohar, T.; Dinevski, D. Adapted User-Centered Design: A Strategy for the Higher User Acceptance of Innovative e-Health Services. Future Internet 2012, 4, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, S.; Zayim, N.; Gulkesen, K.H.; Samur, M.K.; Karaağaoglu, N.; Saka, O. Usability of a Web-Based Personal Nutrition Management Tool. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2011, 36, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heartaround Official Website. Available online: https://heartaround.com/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- WebRTC Official Website. Available online: https://webrtc.org/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Lindberg, T.; Näsänen, R.; Müller, K. How Age Affects the Speed of Perception of Computer Icons. Displays 2006, 27, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanos, C.; Tselios, N.; Xenos, M. Perceived Usability Evaluation of Learning Management Systems: A First Step towards Standardization of the System Usability Scale in Greek. In Proceedings of the 2012 16th Panhellenic Conference on Informatics, Piraeus, Greece, 5–7 October 2012; IEEE: Piraeus, Greece, 2012; pp. 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Firth, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: The Framework Approach. Nurse Res. 2011, 18, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| A/A | Participant | Health Condition | Computer Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female, 63, lives alone | Diabetes type 2, visual impairment | Some experience from work |

| 2 | Male, 67, lives alone | Diabetes type 2, hypertension | None |

| 3 | Male, 72, married | Hypertension | Some experience from work |

| 4 | Male, 71, married | - | Uses computer for simple tasks |

| 5 | Female, 73, married | - | None |

| 6 | Female, 82, lives alone | Arthritis, hearing impairment | None |

| 7 | Female, 68, married | - | Uses computer for recreational purposes |

| 8 | Female, 65, married | - | Has attended a computer seminar |

| 9 | Female, 71, lives alone | Asthma, hypertension | None |

| 10 | Female, 68, married | - | Tablet user |

| 11 | Male, 75, lives alone | Diabetes type 2 | None |

| 12 | Male, 78, lives alone | COPD, hypertension | None |

| Aspect | Lessons Learned |

|---|---|

| User Interface Design |

|

| Hardware |

|

| Functionality |

|

| Understandability |

|

| Motivation to adopt |

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panagopoulos, C.; Menychtas, A.; Tsanakas, P.; Maglogiannis, I. Increasing Usability of Homecare Applications for Older Adults: A Case Study. Designs 2019, 3, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs3020023

Panagopoulos C, Menychtas A, Tsanakas P, Maglogiannis I. Increasing Usability of Homecare Applications for Older Adults: A Case Study. Designs. 2019; 3(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs3020023

Chicago/Turabian StylePanagopoulos, Christos, Andreas Menychtas, Panayiotis Tsanakas, and Ilias Maglogiannis. 2019. "Increasing Usability of Homecare Applications for Older Adults: A Case Study" Designs 3, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs3020023

APA StylePanagopoulos, C., Menychtas, A., Tsanakas, P., & Maglogiannis, I. (2019). Increasing Usability of Homecare Applications for Older Adults: A Case Study. Designs, 3(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs3020023