Abstract

New prospective of chronic low back pain (CLBP) management based on the biopsychosocial model suggests the use of pain education, or neurophysiological pain education, to modify erroneous conceptions of disease and pain, often influenced by fear, anxiety and negative attitudes. The aim of the study is to highlight the evidence on the outcomes of a pain education-oriented approach for the management of CLBP. The search was conducted on the Pubmed, Scopus, Pedro and Cochrane Library databases, leading to 2673 results until September 2021. In total, 13 articles published in the last 10 years were selected as eligible. A total of 6 out of 13 studies support a significant reduction in symptoms in the medium term. Disability is investigated in only 11 of the selected studies, but 7 studies support a clear reduction in the medium-term disability index. It is difficult to assess the effectiveness of the treatments of pain education in patients affected by CLBP, due to the multimodality and heterogeneity of the treatments administered to the experimental group. In general, methods based on pain education or on cognitive-behavioral approaches, in association with physical therapy, appear to be superior to physiotherapeutic interventions alone in the medium term.

1. Introduction

1.1. Pathology and Intervention

The role of psychological factors in the development and persistence of chronic low back pain (CLBP) [1] was largely investigated in the recent literature. In particular, studies have suggested that an increasing negative attitude towards pain, fear of movement or relapses, plays an important role in the etiology of chronic low back pain [2].

Chronic low back pain is one of the most significant and frequent health problems, characterized by medical and economic consequences for the patients themselves and for society, such as increased medical expenses, lost income, lost productivity and a reduction on compensation payments.

The approach to chronic low back pain is multidisciplinary in terms of diagnostic and therapeutic viewpoints.

Medical, paramedical, physiotherapeutic, psychological and holistic methods are all useful in the best approach to this complex illness and to fully understand and treat all of the dimensions and aspects of discomfort felt by the patients.

According to the biopsychosocial model, chronic pain is mainly caused by a nervous system hypersensitivity, rather than the persistence of a lesion at the tissue level [3]. This neuronal hyperexcitability, which in turn causes a lower pain threshold, is due to a plasticity mechanism (known as central sensitization) [4], that is sustained by negative emotions, anxiety, fear, catastrophe and the anticipation of consequences [5]. Therefore, the most recent literature has suggested the use of pain education as a modality to treat chronic pain, particularly in clinical situations characterized by central sensitization, or in the presence of disease and/or pain misconceptions [6].

Lately, one of the most studied and utilized psychotherapeutic methods is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which has been largely supported and aims to explore the links between thoughts, emotions and behaviors. It is a structured approach used to treat some mental health disorders and other illnesses with the aim to alleviate distress by helping patients to develop more adaptive cognitions and behaviors.

Pain education (Pain Neuroscience Education, PNE) is a treatment that consists of educational sessions, especially (but not only) for patients affected by musculoskeletal disorders, aimed at an accurate explanation of the neurophysiology and neurobiology of pain and the process of pain modulation by the central nervous system [7]. The goal is to modify those beliefs, rooted in the psychosocial background of the patient, which feed the persistence of chronic pain, remodeling the perception of pain itself and to draw positive effects, also in functional terms.

1.2. Objective

The purpose of this systematic review is to highlight the most recent scientific evidence on the outcomes of a pain-oriented approach in the management of Chronic Low Back Pain (CLBP).

This paper examines the clinical trials of the last years that carried out pain education/cognitive-behavioral therapy interventions on patients with CLBP and then compared with conventional physiotherapy approaches.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes) guidelines were followed [8].

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Types of Studies

Types of studies included were clinical trials (CT) and randomized controlled trials (RCT), with the aim of evaluation of the efficacy of treatments focused on pain education for the management of CLBP. Only articles published in the last 10 years (from 2011 to 2021) were included. No a priori restrictions were set with respect to number of participants, participants’ assignation, randomization units, number of centers involved or consideration of participant preferences.

2.2.2. Types of Participants

Studies with patients affected by CLBP were included. A temporal threshold of persistence of pain equal to or more than 3 months was established to consider low back pain as chronic, according to the literature by most of the authors [2].

Inclusion Criteria

Studies involving the use of pain education (neurophysiological education of pain) or communicative-educational interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or cognitive functional therapy (CFT), as a single intervention or combined with physiotherapeutic treatments.

- Studies that admitted, as elements of comparison, the conventional low back pain physiotherapeutic protocols.

- Studies that presented additional intervention groups (in addition to the one identified as the experimental group and the control group).

Exclusion Criteria

- Back pain, post-operative lumbar pain and lumbar pain related to specific pathologies;

- Populations with individuals under the age of 18;

- Cardiovascular, psychiatric, rheumatic, neoplastic or inflammatory pathologies.

- Studies that comprised additional pharmacological, instrumental or other interventions, not attributable to physiotherapy techniques.

2.2.3. Types of Outcome

The main outcomes evaluated for eligibility were pain and/or disability.

2.3. Bibliographic Research

The databases “PubMed”, “Scopus”, “Pedro” and “Cochrane Library” were systematically reviewed by three independent authors (RF, UB and FP) from 30th September 2021, according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA).

The keywords “pain education” “cognitive behavioral therapy”, “chronic low back pain” and “chronic lumbar pain” were used for the research. The aforementioned keywords were also searched in the form of mesh terms, and were combined using Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR” and “NOT”) in line with the clinical research question, according to the PICO model [9].The search strings produced are shown in the following table (Table 1). The search produced 2673 results, summed up across the various databases. Two independent reviewers (RF and UB) performed a study quality assessment. Any conflicts were resolved by consulting an additional author (FP)

Table 1.

Search strings used.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of the Articles

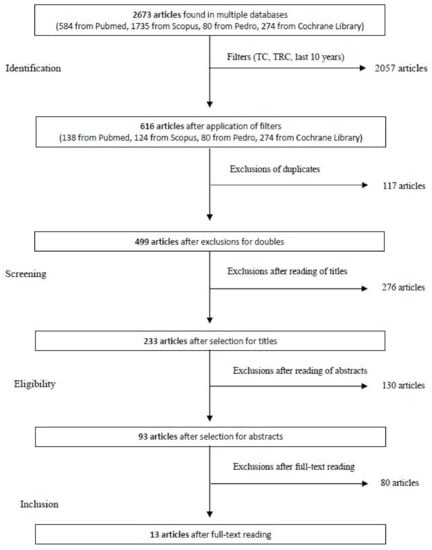

Following the selection made through the filters (CT, CRT and publication in the last 10 years), the identified articles were reduced to 616, divided between Pubmed (138 articles), Scopus (124 articles), Pedro (80 articles) and Cochrane Library (274 articles), then further reduced to 499, after the exclusion of duplicates (117 articles). At this point, the qualifications were screened and 276 articles that did not show relevance to the research question were excluded. The remaining 223 articles were submitted for abstract reading, which excluded a further 130 articles, in favor of 93 eligible articles. A final selection was performed on these articles, reading the full text, and 80 more were excluded, due to the already cited exclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process.

3.2. Bias Risk Assessment in the Included Studies

The assessment of the risk of bias in the studies included in this systematic review was carried out by two authors (RF and UB) using the PEDro scale; this tool allowed us to quickly identify which randomized clinical trials had internal validity (criteria 2–9) and had sufficient statistical information to make the results interpretable (criteria 10–11).

Any conflicts between the two authors were resolved through the comparison or intervention of a third author (FP).

Criterion 1, correlated with external validity (or “generability” or “applicability”), was, however, not used to calculate the total score [10].

The criteria that met each item of the PEDro scale are shown in Table 2:

Table 2.

PEDro Scale. [11].

The following tables show the results of the evaluation according to the PEDro scale for each study (Table 3). Afterwards, the results were summarized and expressed according to the corresponding levels of evidence (LOE) (Table 4).

Table 3.

PEDro scale for each study.

Table 4.

Level of evidence of the included studies.

Based on the results from the PEDro scale data, almost all studies were judged to be at low risk of bias for most of the items. Two studies were considered at high evidence level (level I) [21,23], nine studies at evidence level II [11,12,13,15,16,17,19,20,22] and two (one of which has a quasi-experimental design) with a low level of evidence [14,15].

3.3. Evaluation of External Validity or “Applicability”

Although the inclusion criteria identified studies with rather specific characteristics, with respect to the clinical presentation of symptoms, the duration of symptoms, the age group of the population and the type of interventions administered, there were still discrepancies between the studies. These discrepancies limit the possibility of drawing definitive conclusions about the efficacy of the treatment on the population under examination.

The settings where the studies were carried out were not considered (outpatient regime, hospital, university, specialized pain clinics or nursing homes).

Methods of administering the interventions (both experimental and control) were not homogenous in the programs offered, especially for multimodal interventions (a combination of educational approaches and physiotherapeutic treatments of different types), which made it impossible to determine the real knowledge of the effectiveness of individual treatments. Two studies [7,10] focused on the prevention of all the studies to overlap in a coherent way and evaluated pain as an outcome measure in the subsequent follow-up endpoints, but not the disability index, despite the latter being detected at baseline.

Finally, it is worth noting that the follow-up durations are rather heterogeneous between the studies, constituting a significant uncertainty in identifying the efficacy of the treatment with respect to short (<3 months), medium (from 3 months to 1 year) or long (≥1 year) term.

3.4. Extractions and Characteristics of Datas

In order to extract data from each article independently, a standard data extraction system was used in line with the PICO model of the clinical research question. The data, including the scores relating to the PEDro score and the LOEs of each study, previously obtained, were then organized according to the following parameters, and finally reported in the table (Table 5):

Table 5.

Summary of the articles included.

- General information: Author, year of publication, study design and level of evidence of the study;

- Participants: sample size, age of participants and duration of pain;

- Interventions/Controls: number of participants for each group (experimental and control), content, number of interventions;

- Outcome: type of outcome taken into consideration;

- Follow-up(s): baseline, post-treatment and re-evaluations;

- Results: summary of the results obtained, with mean difference (and standard deviation);

- Score on the PEDro scale.

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to provide the state of the art scientific literature regarding the efficacy of educational techniques in patients with CLBP, based on outcomes related to pain intensity and disability. The 13 included studies (12 CRTs) worked on 1641 participants. The results of the 13 studies were discussed separately, depending on the outcome measures investigated. According to pain reduction, investigated through VAS, NRS, NRS-11, PBI and CPAQ, six studies [11,12,14,18,19,23] out of thirteen significantly supported more evidence in the experimental group than in the control group. Moreover, in favor of the experimental group and to the detriment of the control group, another study [23] showed modest improvements, and one [17] showed a moderate reduction in painful symptoms detected after surgery, but which was not maintained at subsequent endpoints of follow-up. With regard to disability, measured by RDQ, mRDQ, ODI, HFAQ and QBPD, it must be highlighted that only 11 of the 13 included articles investigated this outcome measure, but seven studies supported an evident reduction in the disability index, in favor of the experimental group over the control group [11,12,13,16,18,19,22]. In the remaining studies, improvements were observed under the considered outcome measures, but without highlighting the significant differences between the experimental and control groups. The result would, therefore, be a success rate of the experimental intervention on the control group of 46.2% in relation to the reduction of pain, and of 63.7% in terms of improvements of disability. It is not possible to interpret these percentages in an absolute way, since, as has already been stated in the evaluation of external validity, the durations of the follow-ups were heterogeneous between the studies. For this reason, it was necessary to compare the data obtained from the previous estimates with the duration of the follow-ups that the various studies followed. Therefore, in relation to the endpoints of the studies, it emerged that the duration of the follow-ups was by far the medium term (considering the interval 3 months–1 year). This data, in particular, was found in all six studies (100%) that validated the success of the experimental intervention concerning the pain outcome, and in six [11,12,16,18,19,22] of the seven studies (85.7%) that supported the success of the experimental intervention on the reduction of disability. Another important note, also mentioned in the chapter on applicability, is the impossibility of rigorously drawing conclusions on the effectiveness of the intervention chosen by the clinical research question, due to the different formats used for the administration of the various types of intervention. The interventions performed in the experimental groups, in fact, encompass as a whole: pain education, pain adaptation strategies, CBT, relaxation techniques, cognitive restructuring, reorientation of objectives, deviation of attention, functional education, coping strategies, exposure with pain control and lifestyle change, physiotherapy, manual therapy techniques, Mulligan mobilizations, joint mobilizations, strengthening exercises, motor or sensory-motor control exercises, aerobic exercise, stretching and home physical activity combined in different formats. Similarly, for the control groups, the interventions embraced “packages” with the following variables: physiotherapy, manual therapy techniques, Mulligan mobilizations, joint mobilizations, strengthening exercises, motor control or sensory-motor exercises, aerobic exercise, stretching and physical activity at home. According to the data processed and weighted through the criteria mentioned above, the experimental interventions, usually combined with physiotherapeutic interventions of various types, show fair evidence of success in the medium term, relative to the two established outcomes, in comparison with conventional physiotherapeutic interventions, on patients with CLBP.

Limits of the Study

The most frequent methodological limit concerns the impossibility of obtaining a blind of the subjects and operators, obviously due to the intervention modality chosen by the research question, which provides, in most cases, a face-to-face comparison between patient and therapist. Another element that constitutes a source of bias, found quite frequently, was the analysis by the intention to treatment, a criterion that is at high risk of bias in seven out of the thirteen studies examined. However, the studies in question were also taken into consideration because they are of considerable interest to the research question.

5. Conclusions

It appears difficult to express categorically the efficacy of treatment focused on pain education, or, more broadly, on cognitive behavioral therapy or cognitive functional therapy for patients with CLBP. However, it is possible to state that, based on what was filtered by the studies analyzed, methods based on pain education, CBT or CFT, combined with various types of physiotherapeutic interventions, appear to be superior, with moderate evidence, to physiotherapeutic interventions in the medium term alone (range: 3 months to 1 year) in relation to pain relief and disability reduction in patients with CLBP.

In any case, it could be of a great help to new studies that focus on pain education, in conjunction with standardized physiotherapy treatment for the management of CLBP. Consequently, this latter treatment should ideally be reproduced on the control group, without, obviously, resorting to pain education techniques or cognitive-behavioral approaches. In this way, accurate conclusions can be drawn regarding the effects of implementing pain education in the management of patients with CLBP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F.; methodology, U.B.; software, C.B.; validation, G.T.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, C.B.; resources, U.B.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.; writing—review and editing, G.T.; visualization, V.P.; supervision, G.T.; project administration, V.P.; funding acquisition, V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grotle, M.; Vøllestad, N.K.; Veierød, M.B.; Brox, J.I. Fear-Avoidance Beliefs and Distress in Relation to Disability in Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Pain 2004, 112, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picavet, H.S.J. Pain Catastrophizing and Kinesiophobia: Predictors of Chronic Low Back Pain. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 156, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, S.J. Models of Pain Perception. In Understanding Pain for Better Clinical Practice: A Psychological Perspective; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Schaible, H.-G.; Richter, F. Pathophysiology of Pain. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2004, 389, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, L.; Turk, D. Psychosocial Factors and Central Sensitivity Syndromes. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2015, 11, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Paul van Wilgen, C.; Van Oosterwijck, J.; van Ittersum, M.; Meeus, M. How to Explain Central Sensitization to Patients with ‘Unexplained’ Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: Practice Guidelines. Man. Ther. 2011, 16, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.; Diener, I.; Butler, D.S.; Puentedura, E.J. The Effect of Neuroscience Education on Pain, Disability, Anxiety, and Stress in Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 2041–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.W. Popping the (PICO) Question in Research and Evidence-Based Practice. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2002, 15, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morton, N.A. The PEDro Scale Is a Valid Measure of the Methodological Quality of Clinical Trials: A Demographic Study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodes Pardo, G.; Lluch Girbés, E.; Roussel, N.A.; Gallego Izquierdo, T.; Jiménez Penick, V.; Pecos Martín, D. Pain Neurophysiology Education and Therapeutic Exercise for Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkin, D.C.; Sherman, K.J.; Baloerson, B.H.; Cook, A.J.; Anderson, M.L.; Hawkes, R.J.; Hansen, K.E.; Turner, J.A. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Usual Care on Back Pain and Functional Limitations in Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 315, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Cerrillo, J.L.; Rondón-Ramos, A.; Pérez-González, R.; Clavero-Cano, S. Ensayo no aleatorizado de una intervención educativa basada en principios cognitivo-conductuales para pacientes con lumbalgia crónica inespecífica atendidos en fisioterapia de atención primaria. Aten. Primaria 2016, 48, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khodadad, B.; Letafatkar, A.; Hadadnezhad, M.; Shojaedin, S. Comparing the Effectiveness of Cognitive Functional Treatment and Lumbar Stabilization Treatment on Pain and Movement Control in Patients With Low Back Pain. Sports Health Multidiscip. Approach 2020, 12, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.; Farrell, K.; Landers, M.; Barclay, M.; Goodman, E.; Gillund, J.; McCaffrey, S.; Timmerman, L. The Effect of Manual Therapy and Neuroplasticity Education on Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2017, 25, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, M.; O’Sullivan, P.; Purtill, H.; Bargary, N.; O’Sullivan, K. Cognitive Functional Therapy Compared with a Group-Based Exercise and Education Intervention for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT). Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrozzi, M.J.; Leaver, A.; Ferreira, P.H.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Jones, M.K.; Mackey, M.G. Addition of MoodGYM to Physical Treatments for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2019, 27, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, T.; Anwar, S.; McCracken, L.M.; McGregor, A.; Graham, L.; Collinson, M.; McBeth, J.; Watson, P.; Morley, S.; Henderson, J.; et al. Delivering an Optimised Behavioural Intervention (OBI) to People with Low Back Pain with High Psychological Risk; Results and Lessons Learnt from a Feasibility Randomised Controlled Trial of Contextual Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CCBT) vs. Physiotherapy. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, P.; Sheikhi, B.; Letafatkar, A. Comparing Pain Neuroscience Education Followed by Motor Control Exercises With Group-Based Exercises for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Pract. 2021, 21, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erp, R.M.A.; Huijnen, I.P.J.; Ambergen, A.W.; Verbunt, J.A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M. Biopsychosocial Primary Care versus Physiotherapy as Usual in Chronic Low Back Pain: Results of a Pilot-Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Physiother. 2021, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrau, J.; Hentschke, C.; Peters, S.; Pfeifer, K. Effects of Behavioural Exercise Therapy on the Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation for Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibe Fersum, K.; O’Sullivan, P.; Skouen, J.S.; Smith, A.; Kvåle, A. Efficacy of Classification-based Cognitive Functional Therapy in Patients with Non-specific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Pain 2013, 17, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wälti, P.; Kool, J.; Luomajoki, H. Short-Term Effect on Pain and Function of Neurophysiological Education and Sensorimotor Retraining Compared to Usual Physiotherapy in Patients with Chronic or Recurrent Non-Specific Low Back Pain, a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).