The Effects of Dynamic Stability Training with Inertial Load of Water on Dynamic Balance and Pain in Middle-Aged Women with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

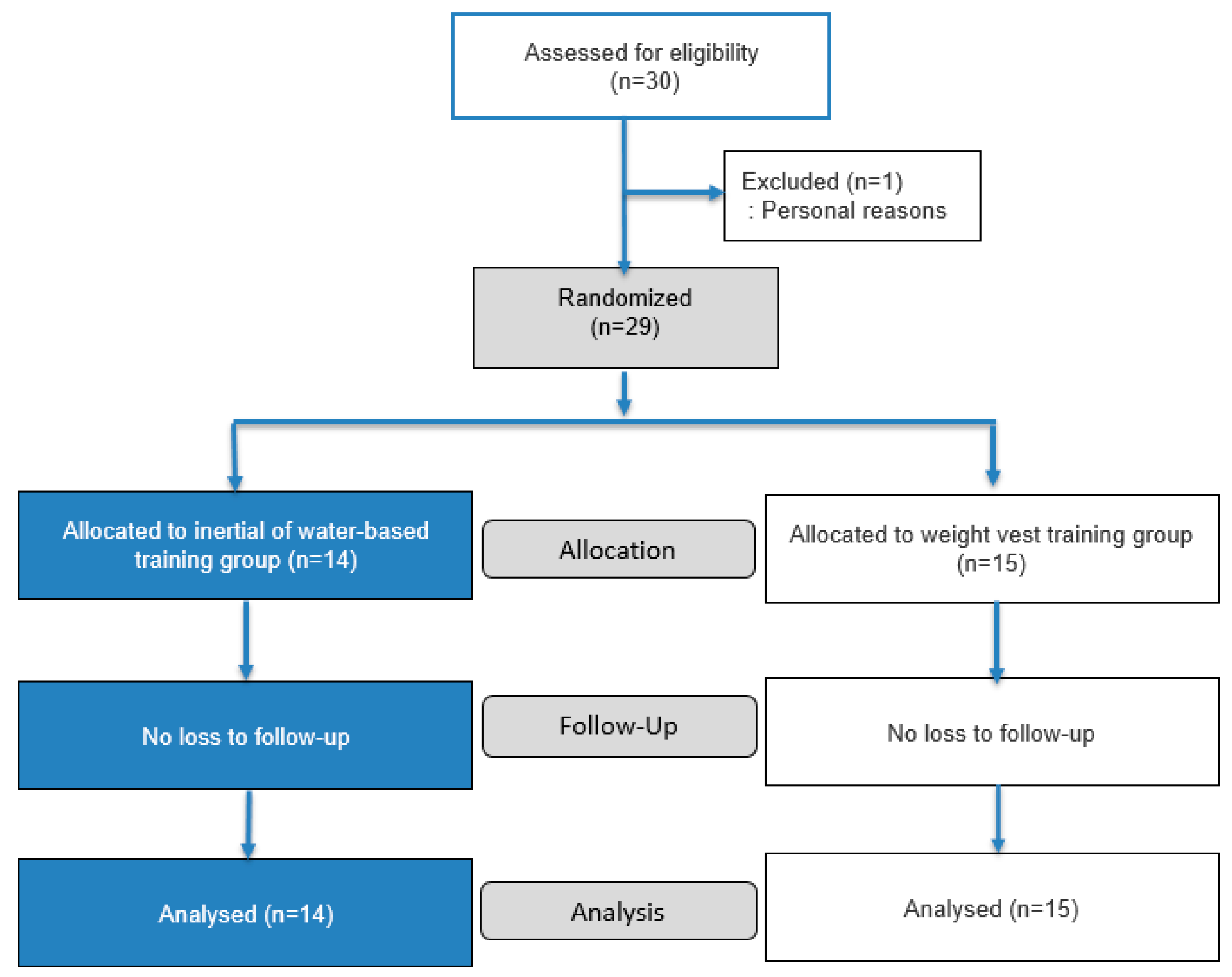

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

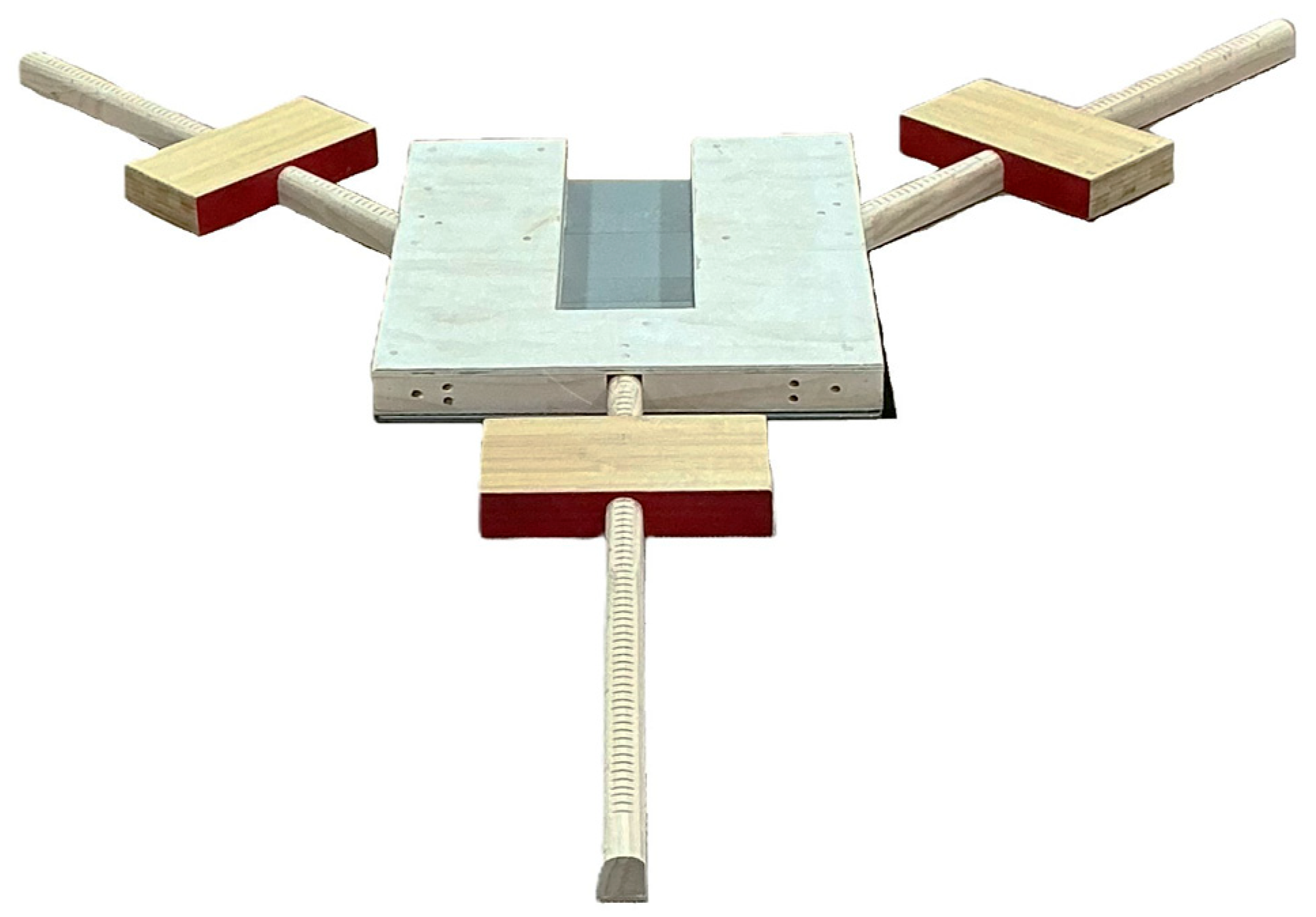

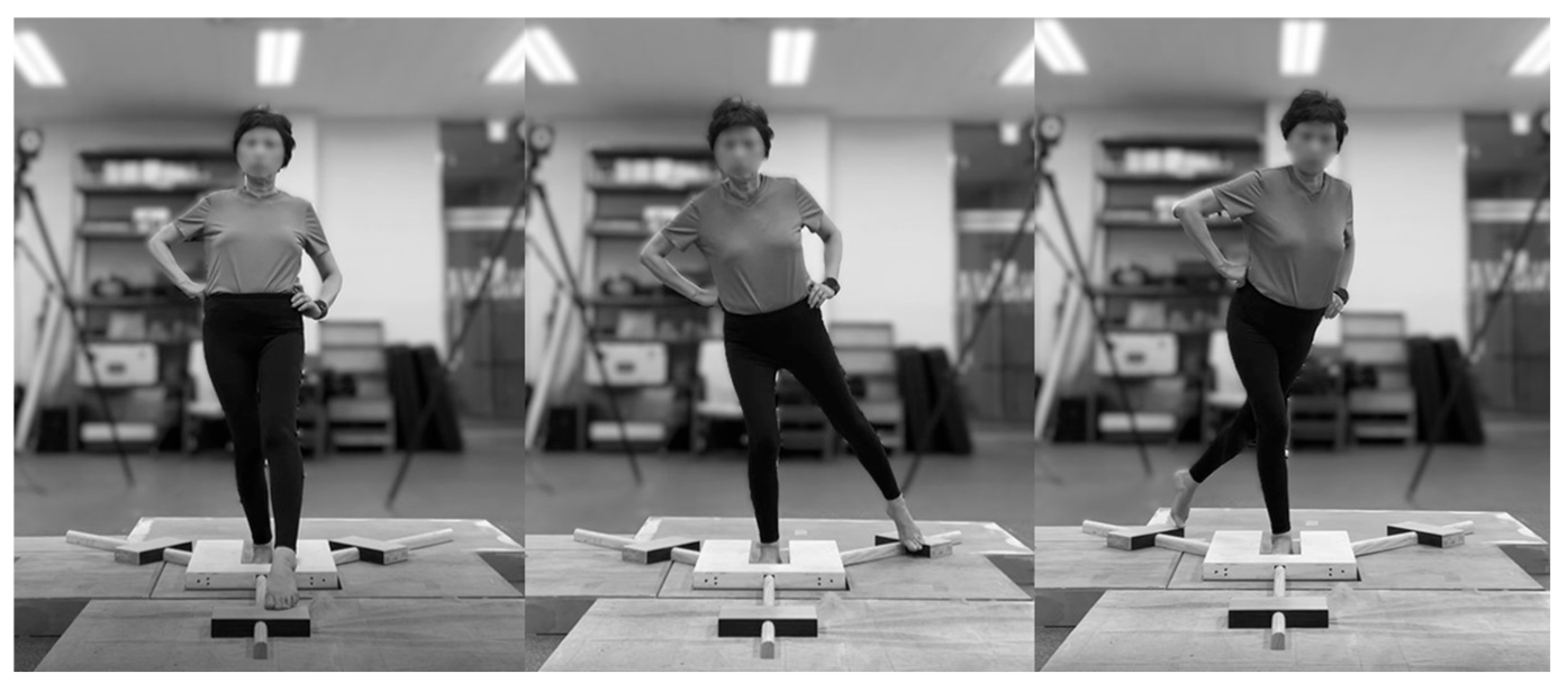

2.2. Assessment of Dynamic Balance

2.3. Assessment of Pain

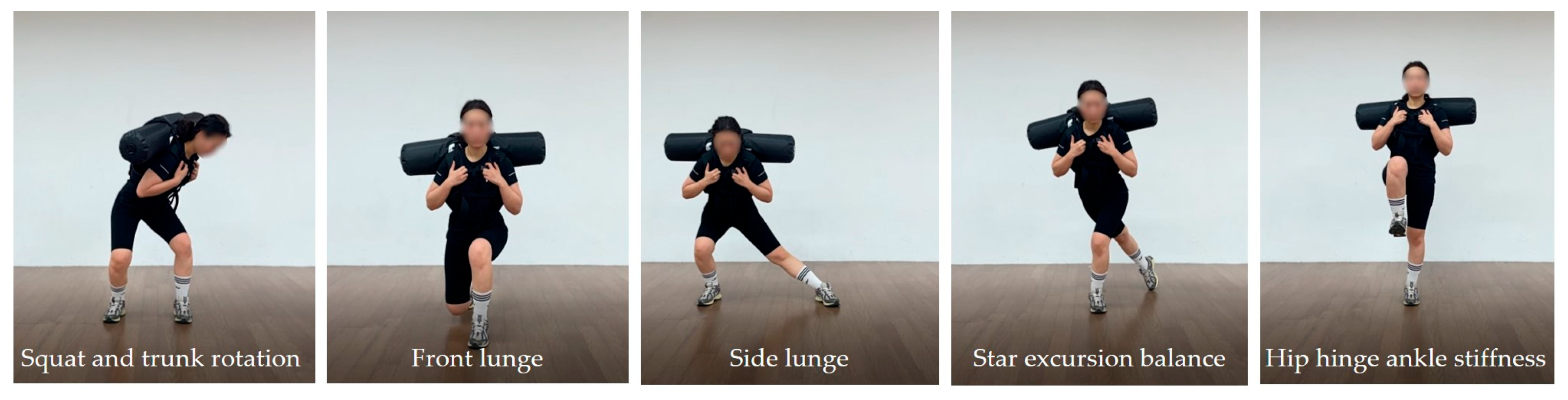

2.4. Exercise Intervention

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. YBT Reach Distance by Direction

3.2. COP of Dynamic Balance

3.3. VAS and TSK

4. Discussion

- Although improvements in dynamic balance may have occurred, the lack of direct neurophysiological measures limits the interpretation of the results.

- The study included only middle-aged women with CLBP and did not classify subtypes or pain patterns, which limits generalizability to the broader CLBP population.

- Despite methodological controls, the potential influence of novelty effects or participant expectations on the outcomes cannot be entirely ruled out.

- The study focused on comparing the effects of specific interventions, which limits the generalizability of the findings.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, H.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, W.M.; Park, S.M. Prevalence of chronic low back pain and its associated factors in the general population of South Korea: A cross-sectional study using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, R.; Raparelli, V.; Bacon, S.L.; Lavoie, K.L.; Pilote, L.; Norris, C.M. Impact of biological sex and gender-related factors on public engagement in protective health behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional analyses from a global survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, L.; Pereira, M.J.; Yap, C.W.; Heng, B.H. Chronic low back pain and its impact on physical function, mental health, and health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study in Singapore. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzoca, D.; Solarino, G.; Pulcrano, A.; Brunetti, G.; Moretti, A.M.; Moretti, L.; Moretti, B. Gender-related issues in the management of low-back pain: A current concepts review. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Chen, S.; Klyne, D.M.; Harrich, D.; Ding, W.; Yang, S.; Han, F.Y. Low back pain and osteoarthritis pain: A perspective of estrogen. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutke, A.; Boissonnault, J.; Brook, G.; Stuge, B. The severity and impact of pelvic girdle pain and low-back pain in pregnancy: A multinational study. J. Women’s Health 2018, 27, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruschak, V.; Cochran, G. Psychosocial predictors in the transition from acute to chronic pain: A systematic review. Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 1151–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, L.E.; Lauver, A.; Ferdon, E.; Schindler, T. Chronic low back pain lowers balance test scores among people who are middle-aged. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2025, 38, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, B.O.; Kahraman, T.; Kalemci, O.; Sengul, Y.S. Gender differences in postural control in people with nonspecific chronic low back pain. Gait Posture 2018, 64, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlazło, M.; Szlacheta, P.; Grajek, M.; Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W.; Rozmiarek, M.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Korzonek-Szlacheta, I. The impact of kinesiophobia on physical activity and quality of life in patients with chronic diseases: A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naugle, K.M.; Blythe, C.; Naugle, K.E.; Keith, N.; Riley, Z.A. Kinesiophobia predicts physical function and physical activity levels in chronic pain-free older adults. Front. Pain Res. 2022, 3, 874205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehre, Y.M.; Alkhathami, K.; Brizzolara, K.; Weber, M.; Wang-Price, S. Effectiveness of spinal stabilization exercises on dynamic balance in adults with chronic low back pain. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2023, 18, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.S.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Tedla, J.S.; Dixit, S.; Gular, K.; Kakaraparthi, V.N. Exploring the interplay between kinesiophobia, lumbar joint position sense, postural stability, and pain in individuals with chronic low back pain: A cross-sectional analysis. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2023, 46, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Farra, F.; Arippa, F.; Cocco, M.; Porcu, E.; Solla, F.; Monticone, M. Is dynamic balance impaired in people with non-specific low back pain when compared to healthy people? A systematic review. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2025, 61, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, R.J. Sensory integration for human balance control. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 159, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sluga, S.P.; Kozinc, Ž. Sensorimotor and proprioceptive exercise programs to improve balance in older adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 34, 12010. [Google Scholar]

- Papalia, G.F.; Papalia, R.; Diaz Balzani, L.A.; Torre, G.; Zampogna, B.; Vasta, S.; Denaro, V. The effects of physical exercise on balance and prevention of falls in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuddin, W.; Vongsirinavarat, M.; Mekhora, K.; Bovonsunthonchai, S.; Adisaipoapun, R. Immediate effects of muscle energy technique and stabilization exercise in patients with chronic low back pain with suspected facet joint origin: A pilot study. Hong Kong Physiother. J. 2020, 40, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, R.A.; Vieira, E.R.; Carvalho, C.E.; Oliveira, M.R.; Amorim, C.F.; Neto, E.N. Age-related differences on low back pain and postural control during one-leg stance: A case–control study. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Li, K.; Yao, X.; Wu, Z.; Yang, Y. Association between functional disability with postural balance among patients with chronic low back pain. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1136137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehre, Y.; Alkhathami, K.; Brizzolara, K.; Weber, M.; Wang-Price, S. Reliability and Validity of the Y-balance Test in Young Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powden, C.J.; Dodds, T.K.; Gabriel, E.H. The reliability of the Star Excursion Balance Test and Lower Quarter Y-Balance Test in healthy adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 14, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plisky, P.; Schwartkopf-Phifer, K.; Huebner, B.; Garner, M.B.; Bullock, G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the Y-Balance Test Lower Quarter: Reliability, discriminant validity, and predictive validity. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 1190–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, T.L.; James, C.R.; Brismée, J.M.; Rogers, T.J.; Gilbert, K.K.; Browne, K.L.; Sizer, P.S. Dynamic balance as measured by the Y-Balance Test is reduced in individuals with low back pain: A cross-sectional comparative study. Phys. Ther. Sport 2016, 22, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, K.L.; Harper, B. Center of Pressure Velocity and Dynamic Postural Control Strategies Vary During Y-Balance and Star Excursion Balance Testing. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2024, 19, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A.; Hartshorne, M.L.; Padua, D.A. Role of thigh muscle strength and joint kinematics in dynamic stability: Implications for Y-Balance test performance. J. Sport Rehabil. 2024, 33, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, S.; Wilson, C.S.; Becker, J. Kinematic and Kinetic Predictors of Y-Balance Test Performance. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizziero, A.; Pellizzon, G.; Vittadini, F.; Bigliardi, D.; Costantino, C. Efficacy of core stability in non-specific chronic low back pain. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, A.; Osuka, S.; Ishida, T.; Saito, Y.; Samukawa, M.; Kasahara, S.; Koshino, Y.; Oikawa, N.; Tohyama, H. Trunk muscle activity and ratio of local muscle to global muscle activity during supine bridge exercises under unstable conditions in young participants with and without chronic low back pain. Healthcare 2024, 12, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.W.; Lee, J.H.; Park, D.H.; Cynn, H.S. Effect of 6-week lumbar stabilization exercise performed on stable versus unstable surfaces in automobile assembly workers with mechanical chronic low back pain. Work 2018, 60, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehsani, F.; Arab, A.M.; Jaberzadeh, S. The effect of surface instability on the differential activation of muscle activity in low back pain patients as compared to healthy individuals: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2017, 30, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrum, C.; Bhatt, T.S.; Gerards, M.H.; Karamanidis, K.; Rogers, M.W.; Lord, S.R.; Okubo, Y. Perturbation-based balance training: Principles, mechanisms and implementation in clinical practice. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 1015394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishan, R.; Badr Ul Islam, F.M.; Shanmugam, S.; Arulsingh, W.; Gopal, K.; Kandakurti, P.K.; Rajasekar, S.; Malik, G.S.; S.G., G. Perturbation-based balance training in adults aged above 55 years with chronic low back pain: A comparison of effects of water versus land medium—A preliminary randomized trial. Curr. Aging Sci. 2024, 17, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, S.C.; Albert, R.W. Compensatory muscle activation during unstable overhead squat using a water-filled training tube. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wezenbeek, E.; Verhaeghe, L.; Laveyne, K.; Ravelingien, L.; Witvrouw, E.; Schuermans, J. The Effect of aquabag use on muscle activation in functional strength training. J. Sport Rehabil. 2022, 31, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Park, I. Effects of Instability Neuromuscular Training Using an Inertial Load of Water on the Balance Ability of Healthy Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Park, I.; Ha, M.S. Effect of dynamic neuromuscular stabilization training using the inertial load of water on functional movement and postural sway in middle-aged women: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, I.B. Effects of Dynamic Stability Training with Water Inertia Load on Gait and Biomechanics in Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Kang, S.; Park, I. Effects of Unstable Exercise Using the Inertial Load of Water on Lower Extremity Kinematics and Center of Pressure During Stair Ambulation in Middle-Aged Women with Degenerative Knee Arthritis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, T.E.; Myklebust, J.B.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Lovett, E.G.; Myklebust, B.M. Measures of postural steadiness: Differences between healthy young and elderly adults. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1996, 43, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesch, K.J.; Tuomisto, S.; Tikkanen, H.O.; Venojärvi, M. Validity and reliability of dynamic and functional balance tests in people aged 19-54: A systematic review. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2024, 19, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, J.; Hadzic, M.; Mugele, H.; Stoll, J.; Mueller, S.; Mayer, F. Effect of high-intensity perturbations during core-specific sensorimotor exercises on trunk muscle activation. J. Biomech. 2018, 70, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berret, B.; Verdel, D.; Burdet, E.; Jean, F. Co-contraction embodies uncertainty: An optimal feedforward strategy for robust motor control. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piscitelli, D.; Falaki, A.; Solnik, S.; Latash, M.L. Anticipatory postural adjustments and anticipatory synergy adjustments: Preparing to a postural perturbation with predictable and unpredictable direction. Exp. Brain Res. 2017, 235, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.H.; Kim, G.M.; Kwon, O.Y.; Weon, J.H.; Oh, J.S.; An, D.H. Relationship Between the Kinematics of the Trunk and Lower Extremity and Performance on the Y-Balance Test. PM&R 2015, 7, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P.W.; Richardson, C.A. Delayed postural contraction of transversus abdominis in low back pain associated with movement of the lower limb. Spine 1998, 23, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.W.; Duncan, M.J.; Price, M.J. The emergence of age-related deterioration in dynamic, but not quiet standing balance abilities among healthy middle-aged adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 140, 111076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macadam, P.; Cronin, J.B.; Feser, E.H. Acute and longitudinal effects of weighted vest training on sprint-running performance: A systematic review. Sports Biomech. 2022, 21, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzwicki, J.T. Weighted vest training in community-dwelling older adults: A randomized, controlled pilot study. Phys. Act. Health 2019, 3, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhi, S.; Pollard, C.D.; Souza, R.B.; Chen, Y.J.; Reischl, S.; Powers, C.M. Trunk position influences the kinematics, kinetics, and muscle activity of the lead lower extremity during the forward lunge exercise. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2008, 38, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, B.L.; Lapinski, S.; Smith, L.; Davies, G. Biomechanical analysis of the anterior lunge during 4 external-load conditions. J. Athl. Train. 2012, 47, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promsri, A.; Haid, T.; Federolf, P. How does lower limb dominance influence postural control movements during single leg stance? Hum. Mov. Sci. 2018, 58, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Melick, N.; Meddeler, B.; Hoogeboom, T.J.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.; van Cingel, R.E. How to determine leg dominance: The agreement between self-reported and observed performance in healthy adults. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2017, 47, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribble, P.A.; Hertel, J. Effect of lower-extremity muscle fatigue on postural control. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, N.W.; Brauer, S.G.; Hodges, P.W. Hip strategy for balance control in quiet standing is reduced in people with low back pain. Spine 2004, 29, E107–E112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhe, A.; Fejer, R.; Walker, B. Center of pressure excursion as a measure of balance performance in patients with non-specific low back pain compared to healthy controls: A systematic review of the literature. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leem, I.; Lee, G.B.; Wang, J.W.; Pyun, S.W.; Kum, C.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.D. Impact of Hip Exercises on Postural Stability and Function in Patients with Chronic Lower Back Pain. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhe, A.; Fejer, R.; Walker, B. Is there a relationship between pain intensity and postural sway in patients with non-specific low back pain? BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehr, A.; Zahednejad, S.; Salehi, R.; Ansar, N.N.; Abbasi, S.; Mohsenifar, H.; Villafañe, J.H. Relationships between muscular impairments, pain, and disability in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A cross sectional study. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2018, 14, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, N.; Becker, L.; Fleig, L.; Schömig, F.; Hoehl, B.U.; Cordes, L.M.S.; Pumberger, M. Objective and subjective assessment of back shape and function in persons with and without low back pain. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Ho, R.L.; Coombes, S.A. The effect of chronic low back pain on postural control during quiet standing: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šarabon, N.; Vreček, N.; Hofer, C.; Löfler, S.; Kozinc, Ž.; Kern, H. Physical Abilities in Low Back Pain Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study with Exploratory Comparison of Patient Subgroups. Life 2021, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M.; Bertrand, A.M.; Robert, T.; Chèze, L. Measuring objective physical activity in people with chronic low back pain using accelerometers: A scoping review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1236143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeuw, M.; Goossens, M.E.J.B.; van Breukelen, G.J.P.; de Jong, J.R.; Heuts, P.H.T.G.; Smeets, R.J.E.M.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S. Exposure in vivo versus operant graded activity in chronic low back pain patients: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain 2008, 138, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karayannis, N.V.; Smeets, R.J.; van den Hoorn, W.; Hodges, P.W. Fear of movement is related to trunk stiffness in low back pain. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhakhan, F.; Sobeih, R.; Falla, D. Effects of exercise/physical activity on fear of movement in people with spine-related pain: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1213199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AG (n =14) | CG (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.85 ± 5.30 | 59.20 ± 4.66 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.31 ± 12.73 | 54.67 ± 9.13 |

| Height (cm) | 159.04 ± 4.16 | 158.19 ± 4.48 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.34 ± 4.31 | 21.79 ± 3.21 |

| Training | 0~6 Weeks | 7~12 Weeks | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | 9~11 RPE with weight (3 kg) 1~2 sets | 9~11 RPE with weight (3 kg) 3 sets | |

| Warm-up | Spine Stretch & Hip Joint, Ankle Mobility | Spine Stretch & Hip Joint, Ankle Mobility | 10 min |

| DST exercise | 1. Two-leg support (Squat) 2. Step movement (front lunge/side lunge/star excursion balance) 3. Single-leg support (one-leg balance) | 1. Two-leg support (Squat and trunk rotation) 2. Step movement (front lunge/side lunge/star excursion balance) 3. Single-leg support (one-leg balance/hip hinge ankle stiffness) | 30 min |

| Cool down | Cat Stretch & Bear Position Hip Flexors & Extensors & Rotators Stretch | Cat Stretch & Bear Position Hip Flexors & Extensors & Rotators Stretch | 10 min |

| Variable | Group | 0 Weeks | 6 Weeks | 12 Weeks | Source | p | η2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT (%) | AG | 62.18 ± 5.30 | 66.26 ± 6.00 | 69.41 ± 5.46 | Time | <0.001 | 0.398 | 0–6 w: 0.011 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.017 |

| CG | 62.38 ± 8.17 | 66.71 ± 7.65 | 64.33 ± 6.19 | Group × Time | 0.002 | 0.200 | 0–6 w: 0.005 0–12 w: 0.423 6–12 w: 0.080 | |

| PM (%) | AG | 91.67 ± 11.18 | 99.28 ± 6.62 | 106.25 ± 7.46 | Time | <0.001 | 0.501 | 0–6 w: 0.004 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.001 |

| CG | 90.51 ± 9.55 | 92.39 ± 9.35 | 97.05 ± 11.05 | Group × Time | 0.021 | 0.133 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.018 6–12 w: 0.031 | |

| PL (%) | AG | 89.39 ± 13.27 | 97.11 ± 6.21 | 102.66 ± 8.77 | Time | <0.001 | 0.377 | 0–6 w: 0.015 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.001 |

| CG | 87.05 ± 10.21 | 91.41 ± 9.68 | 91.66 ± 9.98 | Group × Time | 0.047 | 0.122 | 0–6 w: 0.256 0–12 w: 0.279 6–12 w: 1.000 |

| Variable | Group | 0 Weeks | 6 Weeks | 12 Weeks | Source | p | η2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT (%) | AG | 63.39 ± 5.66 | 65.64 ± 5.36 | 69.02 ± 5.22 | Time | 0.006 | 0.197 | 0–6 w: 0.537 0–12 w: 0.001 6–12 w: 0.006 |

| CG | 62.25 ± 7.43 | 64.75 ± 7.76 | 63.29 ± 6.82 | Group × Time | 0.031 | 0.133 | 0–6 w: 0.369 0–12 w: 1.000 6–12 w: 0.416 | |

| PM (%) | AG | 91.40 ± 10.28 | 99.49 ± 7.49 | 102.27 ± 6.49 | Time | <0.001 | 0.349 | 0–6 w: 0.013 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.356 |

| CG | 90.33 ± 8.84 | 95.95 ± 10.91 | 94.89 ± 9.61 | Group × Time | 0.138 | 0.071 | 0–6 w: 0.100 0–12 w: 0.170 6–12 w: 1.000 | |

| PL (%) | AG | 89.46 ± 10.15 | 96.31 ± 9.49 | 100.97 ± 9.99 | Time | <0.001 | 0.358 | 0–6 w: 0.023 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.053 |

| CG | 87.43 ± 10.93 | 92.00 ± 10.38 | 92.51 ± 8.53 | Group × Time | 0.118 | 0.076 | 0–6 w: 0.170 0–12 w: 0.114 6–12 w: 1.000 |

| Variable | Group | 0 Weeks | 6 Weeks | 12 Weeks | Source | p | η2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP range (mm) | AG | 10.76 ± 3.14 | 10.44 ± 1.75 | 9.49 ± 1.86 | Time | 0.394 | 0.032 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.212 6–12 w: 0.115 |

| CG | 9.45 ± 2.67 | 10.11 ± 1.80 | 9.99 ± 1.88 | Group × Time | 0.104 | 0.084 | 0–6 w: 0.826 0–12 w: 1.000 6–12 w: 1.000 | |

| ML range (mm) | AG | 4.76 ± 2.15 | 7.46 ± 2.08 | 9.92 ± 3.22 | Time | <0.001 | 0.485 | 0–6 w: 0.023 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.025 |

| CG | 5.67 ± 2.24 | 7.85 ± 3.84 | 9.47 ± 3.36 | Group × Time | 0.554 | 0.022 | 0–6 w: 0.070 0–12 w: 0.001 6–12 w: 0.189 | |

| AP velocity (mm/s) | AG | 16.40 ± 4.28 | 16.17 ± 2.31 | 13.74 ± 2.19 | Time | 0.002 | 0.272 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.069 6–12 w: <0.001 |

| CG | 18.16 ± 4.13 | 15.93 ± 2.66 | 15.14 ± 3.41 | Group × Time | 0.251 | 0.050 | 0–6 w: 0.099 0–12 w: 0.026 6–12 w: 0.296 | |

| ML velocity (mm/s) | AG | 12.54 ± 2.51 | 12.54 ± 1.84 | 11.76 ± 2.00 | Time | 0.047 | 0.115 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.875 6–12 w: 0.318 |

| CG | 14.05 ± 2.78 | 12.76 ± 2.05 | 12.48 ± 2.50 | Group × Time | 0.344 | 0.038 | 0–6 w: 0.187 0–12 w: 0.108 6–12 w: 1.000 | |

| AP RMS (mm) | AG | 2.40 ± 0.72 | 2.39 ± 0.47 | 1.99 ± 0.43 | Time | 0.034 | 0.118 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.018 6–12 w: <0.001 |

| CG | 2.00 ± 0.48 | 2.17 ± 0.39 | 2.15 ± 0.39 | Group × Time | 0.007 | 0.188 | 0–6 w: 0.435 0–12 w: 0.824 6–12 w: 1.000 | |

| ML RMS (mm) | AG | 1.05 ± 0.24 | 1.49 ± 0.35 | 2.05 ± 0.74 | Time | <0.001 | 0.501 | 0–6 w: 0.065 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.008 |

| CG | 1.18 ± 0.31 | 1.69 ± 0.88 | 2.00 ± 0.72 | Group × Time | 0.592 | 0.019 | 0–6 w: 0.024 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.190 |

| Variable | Group | 0 Weeks | 6 Weeks | 12 Weeks | Source | p | η2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP range (mm) | AG | 9.89 ± 2.42 | 10.08 ± 1.85 | 8.73 ± 1.61 | Time | 0.004 | 0.185 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.044 6–12 w: 0.006 |

| CG | 9.50 ± 2.19 | 10.07 ± 2.31 | 9.42 ± 1.80 | Group × Time | 0.172 | 0.063 | 0–6 w: 0.473 0–12 w: 1.000 6–12 w: 0.303 | |

| ML range (mm) | AG | 4.82 ± 2.06 | 6.98 ± 1.60 | 8.01 ± 2.13 | Time | <0.001 | 0.469 | 0–6 w: 0.007 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.215 |

| CG | 5.33 ± 1.68 | 6.29 ± 2.56 | 8.24 ± 2.99 | Group × Time | 0.364 | 0.037 | 0–6 w: 0.399 0–12 w: 0.001 6–12 w: 0.003 | |

| AP velocity (mm/s) | AG | 15.91 ± 4.92 | 14.84 ± 3.17 | 13.46 ± 2.17 | Time | 0.010 | 0.182 | 0–6 w: 0.678 0–12 w: 0.024 6–12 w: 0.022 |

| CG | 16.34 ± 2.82 | 15.91 ± 2.44 | 15.19 ± 3.02 | Group × Time | 0.436 | 0.027 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.517 6–12 w: 0.385 | |

| ML velocity (mm/s) | AG | 12.33 ± 3.34 | 12.12 ± 2.49 | 11.48 ± 1.80 | Time | 0.320 | 0.041 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.639 6–12 w: 0.635 |

| CG | 13.06 ± 2.96 | 12.54 ± 2.09 | 12.53 ± 2.60 | Group × Time | 0.744 | 0.009 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 1.000 6–12 w: 1.000 | |

| AP RMS (mm) | AG | 2.10 ± 0.41 | 2.10 ± 0.45 | 2.04 ± 0.44 | Time | 0.495 | 0.026 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 1.000 6–12 w: 1.000 |

| CG | 2.12 ± 0.51 | 2.19 ± 0.52 | 2.12 ± 0.40 | Group × Time | 0.783 | 0.009 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 1.000 6–12 w: 0.785 | |

| ML RMS (mm) | AG | 1.04 ± 0.36 | 1.41 ± 0.34 | 1.60 ± 0.44 | Time | <0.001 | 0.409 | 0–6 w: 0.029 0–12 w: 0.004 6–12 w: 0.257 |

| CG | 1.12 ± 0.20 | 1.30 ± 0.56 | 1.69 ± 0.68 | Group × Time | 0.472 | 0.027 | 0–6 w: 0.513 0–12 w: 0.002 6–12 w: 0.002 |

| Variable | Group | 0 Weeks | 6 Weeks | 12 Weeks | Source | p | η2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | AG | 4.86 ± 1.23 | 3.50 ± 2.28 | 1.64 ± 0.63 | Time | <0.001 | 0.641 | 0–6 w: 0.031 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.004 |

| CG | 4.60 ± 0.99 | 2.60 ± 1.18 | 1.60 ± 0.51 | Group × Time | 0.377 | 0.035 | 0–6 w: 0.001 0–12 w: <0.001 6–12 w: 0.162 | |

| TSK | AG | 43.00 ± 5.38 | 41.00 ± 5.10 | 37.21 ± 4.34 | Time | 0.001 | 0.235 | 0–6 w: 0.347 0–12 w:0.009 6–12 w: 0.058 |

| CG | 37.47 ± 6.29 | 37.47 ± 4.76 | 35.00 ± 7.06 | Group × Time | 0.295 | 0.044 | 0–6 w: 1.000 0–12 w: 0.477 6–12 w: 0.317 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

An, H.Y.; Kang, S.; Park, I.B. The Effects of Dynamic Stability Training with Inertial Load of Water on Dynamic Balance and Pain in Middle-Aged Women with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010014

An HY, Kang S, Park IB. The Effects of Dynamic Stability Training with Inertial Load of Water on Dynamic Balance and Pain in Middle-Aged Women with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Ha Yeong, Shuho Kang, and Il Bong Park. 2026. "The Effects of Dynamic Stability Training with Inertial Load of Water on Dynamic Balance and Pain in Middle-Aged Women with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010014

APA StyleAn, H. Y., Kang, S., & Park, I. B. (2026). The Effects of Dynamic Stability Training with Inertial Load of Water on Dynamic Balance and Pain in Middle-Aged Women with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010014