Abstract

The Death Penalty Information Center’s (DPIC) website states that, since 1608, 576 executions of women under civil authority have been carried out in the United States. The “Espy file”, cited by the DPIC, is widely considered to be the definitive dataset of all executions occurring between 1608 and 2002, but only lists about 365 executions of women. The following two major empirical contributions are offered: (1) source verification of the Espy file, suggesting that black women are especially undercounted and that the total number of executions is closer to 700, and (2) the provision of descriptive statistics demonstrating the variability of women’s to men’s execution ratios over time. This study’s primary purpose is the release and publication of a working dataset, the Women’s Execution Database (WEB), which is meant to generate interest in constructing a narrative that validates the importance of gender-focused theories requiring variables that represent gendered experiences with the death penalty. One example of how such a database can verify women’s erasure in mainstream discussions of capital punishment are WEB statistics demonstrating that active resistance to slavery and racism is verifiable via empirical evidence.

Keywords:

women; executions; capital punishment; Espy file; M. Watt Espy; the Espy Papers; race; intersectionality 1. Introduction

The lack of gendered theorizing in death penalty research cannot be dismissed by virtue of statistics demonstrating the rarity of women’s executions. Indeed, the opposite case is made. Undoubtedly, the number of women executed in the United States pales in comparison to that of men. According to the Death Penalty Information Center [1,2], of the nine executions scheduled for 2026, none are of women. Homicide statistics from the past ten years show that about ten percent of homicides were committed by women (115,817 men, 15,869 women, and 39,259 “unknown” offenders, as derived from the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer) [3]. Even though these statistics do not account for capital offenses, aggravating circumstances, and a myriad of local socio-cultural contexts in sentencing, the fact that men have comprised about 99.08% of the death row population over this same time span gives the impression that, when it comes to women, social and institutional systems are execution averse [4]. Of course, it could be that “certain” men are more likely to be sentenced, just as there are “certain” women who are more likely to be executed. Theories that center on gender and intersectionality offer accounts of gender and racial disparities by incorporating socio-cultural processes, technologies, and punishment, but their explanatory power tends to go unrealized in most quantitative research.

Considering the available information, there is no reason to believe that the death penalty is a zero-sum game. In other words, simply because certain men are punished to death, this does not mean that women will be beneficiaries of a paternalistic system (e.g., life without the possibility of parole (LWOP) versus the death penalty). LWOP has been equated to the death penalty, but the latter sentence receives more possibilities for appeal. The counting of male and female bodies in lieu of examining the meaning and processes of sentencing someone to death is a familiar criticism of the social sciences, but the lack of credibility afforded to those who study how masculinity and power operate is especially pronounced in areas like capital punishment [5,6,7,8]. Put simply, women’s underrepresentation should receive more academic attention or, at the very least, receive as much as men’s overrepresentation.

The ensuing demonstrates one way in which gender has been misrepresented through critique of the “Espy file” [9], which, despite the concerns of the original author, M. Watt Espy, about the database [10,11], is the most prolifically used in quantitative studies including executions from earlier centuries. The dataset’s undercounting of women contributes to various reincarnations of the chivalry hypothesis. These scholarly accounts tend to rely on proportions of familiar indicators like death row sentencing and executions. While the primary mode of approach is to combat statistics with (more) statistics, the theoretical underpinnings are thanks to “outsider” scholarship [12,13,14] and feminist criminology [6,7] that focus on gender and other important social identities (e.g., race) in understanding capital punishment.

Overall, the most cited dataset of all U.S. executions since 1608, known as the Espy file, is also the only known electronic dataset available for quantitative analysis. It contains information on executions of both men and women from 1608 to 2002 and is accessible via the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICSPR) website [9]. After years of research, a dataset of executed women spanning all of American history, encapsulating past and present research and available for rigorous peer review, is now available. A brief review of the chivalry hypothesis and existing scholarship on gender, race, and executions precede the discussion of why, and how, this new dataset (from here on referred to as “WEB”—the Women’s Execution Database) was created as part of a larger project entitled “The Women’s Execution Project”, see https://osf.io/dmw3c/ which contains the link to the google site, that aims to provide a source of data, primary and secondary sources, and present women’s distinctive experiences with the death penalty through critical theorizing; the project is meant to emphasize how social identities, hierarchical rankings, and cultural norms attached to gender and race are instrumental in predicting the “who and why” of those condemned to death. In so-called gender-neutral quantitative studies, social disparities in sentencing outcomes are often treated as the result of a criminal justice system that devalues marginalized groups. The project’s overall approach is to treat social disparities as a way to support institutionalized power sources that require the acceptance of patriarchy, white and class privilege, and heteronormativity to maintain social status on a more systematic level. The statistics presented here offer a glimpse of how the narrative surrounding women’s executions is distorted by failing to account for temporal changes and the serious errors remaining in the Espy file.

2. The Chivalry Chimera and Statistics: A Review of the Literature

The first known U.S. account of women’s underrepresentation as a product of chivalry was articulated in Otto Pollak’s 1950 publication, The Criminality of Women [15]. The accompanying assertion was that women’s official crime rates are higher than those reflected in official records because of women’s ability to disguise their deviance. Famously, some of the more scandalous “evidence” offered by Pollak was women’s proclivity to hide sexual enjoyment [15] (p. 10) and menstruation [15] (p. 126). Men’s superiority is nonetheless safe, as demonstrated by their generosity in protecting the weaker sex from criminal justice repercussions, and the natural deceit of women is evidence of gender inferiority (but, oddly, is not viewed as men’s inability to counter deceit with rationality and proactive policing). The chivalry hypothesis became an attractive modality to preserve patriarchal values by explaining women’s lower arrest and incarceration rates through selective statistics and social stereotyping. It was an alluring combination of positivism, which entailed differential treatment of women ranked on racial hierarchies, social science, unquestioning adherence to the gender binary, and a testament to the existence of natural law.

This hypothesis retains its hold on criminology despite the almost immediate backlash to the book’s publication [16] and the decades that followed [6,17,18]. Earlier quantitative testing found sufficient nuances to discredit its explanatory power. For example, the hypothesis was deemed insufficient in explaining police decisions to arrest [19], except, perhaps, as a way to reinforce gender roles [20]. These findings were found to be applicable in vastly different contexts (e.g., international studies [21]). Later tests yielded similarly nuanced and underwhelming findings despite added sophistication and varying manifestations of the hypothesis—even when applied to capital punishment [22].

The race and gendered aspects of philosophical and jurisprudence-informed perspectives enrich the contextual narrative and demonstrate that micro- and macro-level perspectives can and should be examined together [23,24,25,26]. Qualitative approaches offer detail by concentrating on specific eras in U.S. history and the varied impacts of identity, and have been able to exclusively concentrate on the experiences of executed women [27,28,29,30,31,32]. These approaches have largely emphasized a lack of chivalry in the sentencing of women. Quantitative research, however, tends to overlook the insights of critical theories and resembles the male-dominated criminological scholarship of decades past. A systematic review of gender and death row research found that the effects of gender were overlooked in a number of ways, whether it be through neglect in reporting the gender composition of samples or the overuse of gender-neutral terms, thus avoiding a discussion of gender but presuming the maleness of the subjects [33].

Documenting Executions in the U.S.

As Eschels argued [34], the data and scholarship relied on by courts in capital punishment cases receive little academic scrutiny. Highly regarded organizations like the DPIC represent a relatively small network of scholars. While scholarship on executions has most certainly utilized government and other primary records and the work of well-respected scholars, the unverifiability of historical data, in particular, is troubling [10,34]. It is quite the task to untangle existing data, collect and verify new data, and, potentially the most formidable hurdle, challenge data that have enjoyed decades of mostly uncritical reception by the most reputable of scholars. The Espy File is almost synonymous, though certainly provides a less cumbersome title, with being “the dataset of all state-sanctioned executions occurring on American territory from 1608 to 002”. The details of how the Espy file has become the most cited dataset in death penalty research are not entirely clear. Emerging and existing research suggests that those who collected and contributed to the data—most notably M. Watt Espy himself—have had little to no input in the file’s creation [11,35]. The Espy file’s title credits the author for his years of research, but is an incomplete representation of M. Watt Espy’s life work [33], which is maintained by the M.E. Grenander Library’s Department of Special Collections and Archives at the University of Albany [35].

Certainly, many have researched women’s executions, but it is a committed few, notwithstanding M. Watt Espy, who have catalogued women’s executions for the entirety of U.S. history (namely Victor L.Streib and David V. Baker [36,37,38]. Descriptive statistics of executed women exist, but, up until now, have received little verification and are provided in only the one electronic dataset [34]. This study aims to showcase some of the preliminary findings that suggest that chivalry has not been a defining characteristic of women’s death penalty experiences. Releasing the WEB and representing women’s unique experiences is very much dependent on race, social and racial ranking, adherence to the cult of true womanhood, and the types of gendered crimes committed.

3. Data Description and Methods

The DPIC’s impact is difficult to overstate and ranges from its work with organizations like the Marshall Project, the Equal Justice Initiative, and the Innocence Project to its collaborations with international organizations and activist pursuits. Presenting accurate data and scholarly research is vital to the DPIC’s mission, and they are, arguably, the most commonly relied upon resource for statistics pertaining to the death penalty. It is Baker’s Women and Capital Punishment in the United States: An Analytical History that, to date, provides the most complete listing of executed women, for the reason that he incorporates the extensive research conducted by colleagues and predecessors [38]. While cited extensively on the DPIC website, Baker’s data on executed women are nebulously represented. The DPIC’s page entitled “Executions of Women” contains the following statement:

The actual execution of female offenders is quite rare, with only 576 documented instances as of 31 December 2022 …which constitute about 3.6% of the total of 16,047 confirmed executions in the United States (including the colonies) between 1608 and 2022.[4]

These 16,047 executions are derived from combining Espy file data, which lists 15,269 executions up until 2002, with DPIC data (up until the end of 2021). The Espy file contains the executions of 14,750 men and 365 women. One of the guiding questions for this study was the origin of the estimated total of “576”, given that, since 2002, only ten women have been executed and scholarly research like that of Baker’s estimates the number to be closer to 700 [38].

It does appear that the “576” estimate is derived from Victor Streib’s data. Baker eferences Streib’s work as listing “567” women. This suggests that the DPIC added ten executions to Streib’s estimate [38]. Still, the number “567” is ubiquitous in studies of the death penalty, but mostly uncontested. Accomplished Professor of Journalism Marlin Shipman, whose book of executed women in the 19th and 20th centuries arguably offers the most comprehensive and intellectually compelling account of that time period to date, begins with the uncited statement that “about 560 women have been executed” [31] (p. 1). While Streib’s work is most likely the source of this and numerous other works about executed women, Streib’s data appears to be a result of M. Watt Espy’s research, as contained in the Espy Papers [35].

Baker’s estimate of 702 executions up until 2015 [38] (p. 31) intimates that the percentage of women executed since 1632 might be closer to 4.4% (if using the DPIC metric), or 4.3% if one were to subtract the 365 women and 154 people of an unknown gender from the total (because the assumption appears to be that the 154 “unknowns” are men) and add the 702 to both the numerator and the denominator of the calculated proportion. Whichever estimate is chosen, it is higher than 3.6%, but, more importantly, one estimate for the span of hundreds of years obscures the variability over time. In earlier years, women’s executions paralleled (or even exceeded) those of men. Perhaps even more compelling are the years that do not challenge the overall expectation that women are executed less than men are, but are demonstrative of proportional fluctuations that merit further inquiry. Before examining these historical fluctuations, the next section summarizes what proved to be an extensive and ongoing verification process of original sources and cross-checking existing data sources.

Just as Baker used the Espy file as a “starting point” [38] (p. 31) and supported the data with a myriad of sources [1,3,31,36,39], the framework for the WEB is due to his listing of executed women up until 2015 [38] (pp. 42–63, provided in table format). Each of the named executed women received careful verification—especially those with unclear case details. Not all of the women listed in the table [38] (pp. 42–63) were discussed in the remainder of Baker’s book and, thus, required substantiation from records that were likely inaccessible at the time of his writing. Baker also included six women for whom he could not verify their names or the dates of their executions. However, one of the six, “unnamed (Calvert)”, a black slave who might have been executed in Arkansas, may have been a woman by the name of Mandy Buford. Her 61-year-old niece, Lucindy Allison, was interviewed in 1936 as part of the Federal Writers’ Project [40] (pp. 41–43). She claimed that Buford lived to tell the tale of the “murder” she may or may not have committed. Mandy Buford, at least at the time of this writing, does not appear in the WEB. The WEB, as part of the Women’s execution project, provides a list of sources used and is continually updated as more primary sources are located.

Baker’s data were initially entered into a spreadsheet for comparison to the Espy file. All entries received verification from multiple sources but, due to conflicting execution dates, misspellings, and typos in the Espy file (e.g., 101 names required corrections), Espy file executions that differed from those of Baker’s listing and were unverified in Baker’s book were addressed first. One such an example was “Grace”, a black indentured servant convicted of neonaticide, not listed in the Espy file, who was found in Baker’s listing but not discussed further in the book. From Baker’s listing, it could be deduced that Grace was executed with Elizabeth Emerson (a white woman also convicted of neonaticide and discussed in Baker’s book). In this case, as for other earlier executions, the diary entries of the well-known U.S. historical figure, Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather, were indispensable [41]. From an excerpt of his diary, it was deduced that Grace did, indeed, exist and was executed:

A young Woman of Haverhill (and a Negro Woman also of this Town) were under sentence of Death, for the Murdering of their Bastard-children. Many and many a weary Hour, did I spend in the Prison, to serve the Souls of those miserable Creatures; and I had Opportunities in my own Congregation, to speak to them, and form them, to vast Multitudes of others.[41]

While older executions certainly require more time to verify, historical documentation is available, frequently from the Espy Papers themselves. For example, Sandy (slave owner name “Boyer) was not included in the Espy File, but was found in the Espy Papers. Court records were also an invaluable source for fact-checking, even for 20th-century executions for which court records were not as easily located. The details for Ann Knight, a black woman executed in 1922, were missing from Baker’s data and the Espy file, but, after finding her record in in the Espy Papers, her case could be further substantiated from a court transcript [42]. While Baker may not have cited each woman’s execution, his table and the other material contained within his book certainly made the process less cumbersome.

The Espy file contains misspellings and misclassifications for both men and women, but the very fact that women’s executions were as undercounted as they were (whereas men’s are likely an overcount) is of profound consequence. To provide one example, the most women unaccounted for in one year might have been in 1851. Seven black women, all slaves in Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, were added thanks to Baker [38]. For that year, the Espy listed only one woman, “Fox Mily”, executed in Louisiana, but Baker’s research correctly identified her as “Mily”, her “owner” as the Fox family, and her place of execution as Mississippi [38] (p. 115). In other words, the statistics presented here reflect the eight women executed in 1851, but their names and places of execution are found in the database. While the WEB project is ongoing, the database, thus far, provides a solid foundation for further analyses.

4. Results

Baker’s data [38] (pp. 42–63), once converted into an electronic datafile, were supplemented with DPIC data (beginning in 1984 with Velma Barfield), resulting in a total of 698 executions from 1632 to 2021. While no discrepancies were found in later years, the differences between Baker’s research and the Espy file are still in process of being identified and itemized as part of the WEB project. Table 1 arranges the 310 additional women identified by Baker by the crimes for which they were executed. Not visible are categories that did not require correction (adultery, espionage, and violation of banishment) or executions occurring after 2002 (the last year of the Espy file).

Table 1.

The crimes and racial identifies of executed women as per additions up until 2002.

The previously excluded women were disproportionately black. Of the 310 women, 195 were identified as being black (62.9%), 52 as white (16.8%), 2 as Native American (1.0%), 2 as Spanish (1%), 1 as Hawaiian, and 1 woman was identified as Hispanic. The remaining 20 (6.5%) were women whose racial designations are currently unknown. To reiterate, the racial classifications used were those of Baker and the DPIC. Importantly, while the percentage of black women remains about the same (58.3% versus 57.6% in the Espy file), the percentage of white women in the updated dataset drops from 40.1% (138 out of 364) to 28.1% (190 out of 674), demonstrating the lack of racial representation in the Espy file.

The number of women executed under the generic umbrella term “murder” remains the highest category for the primary crime committed, but drops from 65% (n = 225) in the Espy File to 42% (n = 281) in the updated file (again, for years up until 2002). Baker’s additions of child murder, infanticide, and spousal murder are helpful in narrowing down the cause for the execution. Witchcraft, the second-highest category in the Espy file, accounted for 7.5% (n = 26) of executions, but dropped to 4.8% (n = 32) in the updated version. In the updated version, the second-highest category was infanticide (n = 88, 13.2%) and the third-highest category was spousal murder (n = 47, 13.2%). However, with the now previously missing 33 black women identified by Baker, a tie for the third-highest category is arson (n = 47, 13.2%), and the fourth-highest category is attempted/conspiracy to murder/poison (n = 36, 5.4%). These two categories previously represented, respectively, 5.8% (n = 20) and 3.4% (n = 15) in the Espy file. To summarize, for these categories, the addition of the 71 black women completely altered the statistical distribution of the cause of executions.

4.1. Proportions of Women to Men over Time

There were 36 years, beginning in 1641 and ending in 1862, during which the Espy file does not list any executions of women. Baker identified fifty-seven women executed during these years (see Appendix A for a complete listing of the women and their crimes). Of these 36 years, there are seven years (1650, 1654, 1668, 1687, 1694, 1703, and 1711) during which the Espy file does not list any executions whatsoever, meaning that these years might not have seen any male executions either (with the caveat that men’s executions have not been verified in this study). The Appendix does not include those women for which the Espy file lists an erroneous execution date, but the total count is not affected. So, for example, in 1854, the Espy file does not identify any women, even though, according to Baker, one of the women, Jane Elkins, was executed in that year [38]. However, given that the Espy file does include Jane Elkins—just not for that year (1853 instead of 1854)—Jane Elkins is not among those listed in Appendix A.

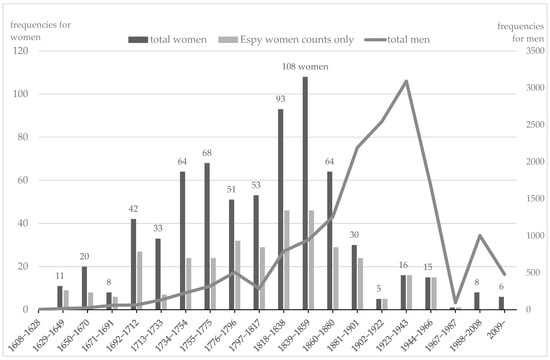

Figure 1 displays the change in ratios over time (in 20-year intervals) and provides the absolute numbers of men and women executed during those time intervals. The total counts of women are derived from the WEB and contain the Espy counts, which are included to indicate how much improvement is offered by the new database. Indeed, a pattern seems more visible, in that women’s executions increased as well as those of men, but just around the time that women’s executions peaked and began to decline, men’s experienced a dramatic increase. Moreover, as the next figure better illustrates, the proportion of men to women was relatively equal until the early 1700s. Then, in the early 1900s, there was the lowest number of women’s executions since the late 1600s, while seeing some of the highest executions of men. In 20 of the 48 years between 1896 and 1944, a time period characterized by two world wars and the Great Depression, the highest number of men’s executions (n = 2931) was observed, also coinciding with the lowest number of women’s executions (n = 27).

Figure 1.

Total counts of men and women executed by 20-year intervals.

4.2. A Closer Look: Pre and the American Revolution Years

Between 1608 with the first recorded execution of George Kendall and the 1630 execution of John Billington, there were five executions of men before the first woman, June Champion, would die by hanging in 1632. According to the Espy file, the total number of executions up until 1762 was 661—564 men, 81 women, and 16 “unknowns”. In total, 117 more women were identified during this period, indicating that that about 25% of executions were of women (198 women out of 778 total). In other words, were one to rely exclusively on the Espy file for executions up until 1762, the percentage of women would be less than half the actual number; thus, 12.5% of all executions rather than 25%.

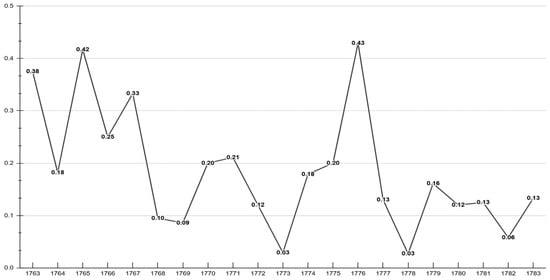

During the American Revolution, from 1763 to 1783, at least one woman was executed every year (n = 75), meaning that men’s executions (ostensibly under civil authority) can best be compared to women’s during this time period (see Figure 2). However, the noticeable spikes may very well be due to errors in including men who were not executed “under civil authority”. The figure contains a couple of examples in which this might have been the case.

Figure 2.

Proportions of women to men executed during the Revolutionary Years.

This figure demonstrates the variability of executions, beginning with about 38% of executions in 1763 being of women and ending with 13% of executions being of women in 1783. Even at its lowest, 2.9% in 1773, the ratio is higher than that of any year in the modern era. In both 1765 and 1776, men and women’s executions are almost on par with one another. To reiterate, the Espy file inflates the number of men’s executions by including “military” executions and questionable and unverified “state-sanctioned” executions of slaves [10] (pp. 220–222).

5. Discussion

For the first 100 years of what would become the United States, there were years in which women were executed in almost equal numbers to men. The increase in men’s executions might be due to military-sanctioned executions erroneously included in the Espy file, but also the turmoil that preceded American society before the war began. Almost half of all men’s executions (up to 1783) occurred between 1735 and 1762, the three decades leading up to the Revolutionary War. Still, this overcount of men is visible in later years as well.

From the Civil War era, the Espy file includes all the executions for the prewar actions of John Brown and his colleagues, most of the controversial executions by the Confederate forces in North Carolina of 22 captured Union soldiers for alleged desertion from the South, and the 1862 military execution of 38 Dakotas for an Indian uprising in Minnesota [10] (pp. 216–217).

The Espy file explicitly states that military executions are not counted, but includes twenty-five executions for desertion in 1864 alone. Due to the coding of these executions, verifications are required. Then, there are less clear but plausible miliary-sanctioned executions to be found by examining the occupations, instead of examining only the recorded reasons provided in the file for executing these men. In the Espy file, there were 16 Army deserters, 7 AWOL soldiers, and 119 soldiers [9].

In the miscoding of men’s occupations, the lack of attention paid to women’s occupations is also apparent. Of the 229 executions for piracy, all were of men [9]. Only the infamous woman pirate Rachel Wall, executed in 1789, was assigned the occupation of “pirate,” though, according to both Baker and the Espy file, she was executed for robbery and not “piracy” [9,38]. For men, according to Blackman and McLaughlin’s research, misclassifications led to an undercount of executions for “piracy” and an overcount of executions falling under the generic, catch-all “murder” category [10] (p. 212). The consequence of this being that those quantitative studies relying only on the Espy file would not only seriously misrepresent identity, but also the conditions under which men and women were executed.

The most consequential finding of this study is the inadequacy of the Espy file in representing the executions of black women [38]. Some of these omissions stemmed from misspellings and typos, which may have also led to some misgendering. Other possibilities for their omission are troublesome in their implications of coder bias; for example, that all slaves were men and/or that slave women’s deaths were not important enough to document. Perhaps the collectors of the Espy file were unfamiliar with the theoretical contributions of black feminists and scholars whose research on black women’s participation and leadership in slave rebellions is a meaningful part of American history [43,44]. This would not be an unreasonable assumption given that the coders were undergraduate students with little direction [35] To illustrate, if only reading the data contained in the Espy file, one would be aware that a black slave woman “belonging to” William Hallett took part in “a murder”. Supplementary research suggests that a woman, and the accomplices she led, ax-murdered Hallett, his pregnant wife, and their five children [39] (p. 6). We know from the Espy file that her execution involved burning, but, from Hearn’s research and the Espy Papers, it seems that she was “roasted” alive for hours [39] (p. 6). Infanticide and other acts of murder were directly linked to active resistance to slavery by black women [43,44], but, through data omission and minimization, are too often overlooked.

To accept that the current qualitative and historical research suffices as long as it does not challenge quantitative research and to justify the (many) mistakes of the Espy file by claiming “awareness of its issues” is a disservice to academia, a system that relies on the accuracy of data, and M. Watt Espy himself. Quite possibly, more global attention than ever before is uncovering the gendered circumstances of women’s executions in the international arena (Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide [45]). The lack of accurate and available quantitative data can be explained by apathy and, now especially, the political suppression of research that contests mainstream data and scholarship—no matter how flawed and antiquated these data are. University students who (are able to) take courses in critical race theory, history, African American studies, and gender studies might be exposed to the scholarship of scholarly giants as Professor Angela Harris, but will likely be unaware of the Espy file. Quantitative scholars, no matter how well-versed in the literature, will, however, continue to use it, as they have for decades, unless there is enough empirical support to convince them otherwise [33].

The table and figures produced from the data are not only an attempt to improve upon the scholarship on gender and the death penalty, but are also meant as fodder for reflection and stimulation for further research. The non-trivial number of women who were initially overlooked, combined with research suggesting that “extra-legal” means of execution were reserved for women accused of witchcraft or similarly gendered crimes that disproportionately blamed women, suggests that we need to revisit how “state-sanctioned” executions are defined. In other words, if the masculinity of military participation is to be taken for granted so as to (over)count executions that are primarily reserved for men, then the argument could be made that deaths that resulted from the violation of feminine gender norms or being the sexual assault victims of vengeful slave owners, for example, should also be included.

Still, the overall steady proportional decline in executions of women to men is unlikely to change, regardless of modifications in the coding of executions. But the Espy file is not representative of women’s experiences with capital punishment in the United States, and it certainly should not be considered as the basis for theoretical contributions to death penalty research without significant improvements.

6. Implications and Recommendations

The widespread acceptance of the Espy file (and scholarly indifference to the Espy Papers [35]) has garnered enough judicial and scholarly inertia to render serious inquiry an uphill battle for even the most intrepid of researchers. Organizations like the American Bar Association (ABA) are reliant on the DPIC, which, in turn, is dependent on data like the Espy file. The ABA’s Death Penalty Policies have all, in some way, cited DPIC data [46] (pp. 22–33). In other words, the policy implications are vast. Those who wish to demonstrate biases in the system, challenge existing doctrine and decisions, and educate practitioners on how we can better serve clients in the criminal justice system might find that gender identity and theory are invaluable tools. The “otherness” of women executed has true potential for objective research and data collection that challenge dominant narratives through a different lens and contextual approach.

Incorporating context should include widening the scope of inquiry by seeking assistance from the international community of scholars and recognizing that time and space extend beyond national borders. Jack Graham might have been America’s first mass murderer via a commercial flight in 1955, but was likely influenced by Albert Guay (responsible for the bombing of a Quebec airliner in 1949). Jack was presumably angry with his mother and Albert with his wife, and both committed similar crimes with similar motivations (insurance money and women), but the latter, Guay, had a female coconspirator whose participation has been largely overshadowed by the enormity of that tragedy. That woman, Marguerite Pitre, in 1953, would become the last woman executed in Canada. In the United States, 1953 was also a year of consequential executions of women, but certainly did not result in the last. These women, Earle Dennison, Bonnie Heady, and Ethel Rosenberg, were also notorious in their own right, and their crimes were extensively covered by the media. While certainly representative of a more punitive and fearful global era defined largely by the Cold War, executions of U.S. women, unlike Canada, did not cease. This occurred despite Ethel Rosenberg’s global impact [47].

Aside from identifying parallels in crime typologies and offender characteristics, datasets like the WEB can assist scholars in drawing connections between cases, extending beyond mere similarities to exploring the ways in which women’s rights, institutional and systemic processes, and political and social events are interconnected. The scholarship exists, much of it in research hubs like the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide, but for scholars without the means to publish, they might find this work and the WEB useful for the development of larger theoretical frameworks that combine differences and likenesses and create a more parsimonious model of how gender, power, and the death penalty operate—particularly one that is culturally informed and relies on the experiential knowledge of global scholars. By identifying themes among the crimes women are sentenced for and how media and the public participate in othering the condemned, scholarship can also expand its reach and intellectual approach. Participation in a democratic exchange of ideas might be more equipped than the mere exchange of data to answer the following questions: Why at this time, this place, and under what conditions? How have similar locales produced different outcomes? What is the future of the death penalty given local, state, and global trends in punishment and justice?

7. Conclusions

The gender gap in executions over the last one hundred years of U.S. executions has grown so massive that any inferences that are uninformed by gender theory are seriously missing the mark. Yet, theoretical and non-quantitative methods are dispersed across disciplines such that they seem to have escaped the notice of policymakers and the institutions responsible for capital punishment decision making. Mainstream criminal justice and legal scholars agree that the past one hundred years are characterized by the expansion of the criminal justice system, the social acknowledgment of violence against women and children, technological advances that have allowed for the better detection and apprehension of criminals, and recognition that the racist patterns of the past are deeply entrenched in ways that extend beyond the criminal justice system. Black feminists and critical theorists have successfully demonstrated how social identity and power are enduring institutional features that continue to marginalize the vulnerable and reward the powerful through minimization and silencing. When it comes to the death penalty, casual reformulations of the chivalry hypothesis appear to resonate most in collective cultural understandings of women’s underrepresentation. It supplies an easy answer, in part because it has not generated enough interest to challenge the obvious numerical discrepancies.

Blackman and McLaughlin’s research served as an invaluable source of empirical and professional validation. Their fearless critique of established experts in the field is a necessary aide-mémoire that science should thoughtfully consider new information and can incorporate the new without destruction of the old. Inquisitiveness is a quality to be cultivated, but, as a warning to future researchers, the U.S. Espy file is so venerated that its adherents are not necessarily aware of its origins and the treasure trove of data that Espy collected. There are times when replacements are necessary, but, ironically, a replacement in this case involves the author’s own research [33]. Gendered scholarly preconceptions and approaches do matter and how the data are collected is as important as how they are interpreted. Blackman and McLaughlin conclude with “the best advice for scholars desirous of quantitative analyses of American executions is, ‘user beware’” [10] (p. 222). With full awareness that their work laid the groundwork for the concluding statement of this study, it is time for a moratorium on the Espy file and for those seeking quantitative data on women’s executions. The WEB provides the names of women who have been excluded from previous analyses, but, more significantly, offers variables that prior quantitative analyses have largely omitted. The codebook and variable justifications and sources are found on the Women’s Execution Project website. Some of these variables include the following:

Victim(’s) gender/race and relationship to the executed, accomplice data including criminal justice outcomes, parental status, and number of children, variables that assess emotional and mental health, trauma, sexual and domestic assault history, gendered motivations for the crime, more nuanced measures of occupational status and history, media representations and advocacy, drug and alcohol abuse, treatment in the criminal justice system (e.g., reliance on sexist stereotypes in prosecutorial strategies and jury composition).

The work is ongoing, data collection is transparent and democratic, and all manners of analyses and interpretation are welcome.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study can be accessed and downloaded directly from the following web address: https://sites.google.com/southalabama.edu/the-womens-execution-project/the-dataset/introducing-the-womens-execution-database_data-for-sexes-publication. You may also choose to access the data from that same website by visiting the Women’s Execution Project website at https://osf.io/dmw3c/ or contacting the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DPIC | Death Penalty Information Center |

| FBI | Federal Bureau of Investigations |

| ICPSR | Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research |

| WEB | Women’s Execution Database |

Appendix A. The “Missing” Women for Years During Which the Espy File Reports No Executions of Women

| Years | Identity of Women, Crimes Committed, Mode and Place of Execution | Ratio |

| 1641 | An unnamed black woman was hanged for arson in Charleston, South Carolina. | 1:2 |

| 1650 | Alice Lake, a white woman, was hanged for witchcraft in Suffolk, South Carolina. | 1:0 |

| 1654 | Mary Lee and Lydia Gilbert, both white, were hanged for witchcraft in Maryland and Connecticut (respectively). | 2:0 |

| 1658 | Eliza Richardson (for witchcraft), Mary Williams (for theft), and Mary Clocker (for theft) were all white women hanged in Maryland. | 3:1 |

| 1659 | Katharine Grady, a white woman, was hanged for witchcraft in Virginia. | 1:3 |

| 1664 | Elizabeth Greene, a white woman, was hanged for infanticide in St. Mary’s, Connecticut. | 1:0 |

| 1668 | Ruth Briggs and an unnamed woman, both white, were hanged for infanticide in Hartford, Connecticut, and Essex, Massachusetts (respectively). | 2:0 |

| 1669 | Angel Hendricks, a white woman, was hanged in Manhattan, New York, for infanticide. | 1:1 |

| 1687 | An unnamed white woman was hanged in Bristol, Rhode Island, for infanticide. | 1:0 |

| 1694 | Elizabeth Lewis (unknown race) was executed for an unknown reason in Virginia. | 1:1 |

| 1703 | Margaret Ward, a white woman, was executed for murder in Anne Arundel, Maryland. | 1:0 |

| 1707 | Margaret Caine, a white woman, was executed for murder in Charles, Maryland. | 1:2 |

| 1709 | One unnamed black woman was executed for arson in South Carolina | 1:2 |

| 1711 | Waisoiusksquaw, a Native American woman, was hanged for spousal murder in Hartford, Connecticut. | 1:0 |

| 1714 | Deborah Gryce, a white woman, hanged in Rhode Island, New York, for infanticide. | 1:1 |

| 1720 | Two white women, Elizabeth Atwood and Magdalen Collar, were hanged for infanticide in Massachusetts and North Carolina (respectively). | 2:10 |

| 1722 | Two white women, Anne Robinson and Eleanor Moore, were executed for burglary in New Castle, Maryland, and for murder in New Castle, Delaware. | 2:5 |

| 1723 | Four white women (Mary Reed, Eleanor Carrah, Mary Burrass, and Mary Mounting) were executed for theft. Hannah (Galloway), a black woman, died via gibbeting for murder. All were executed in Maryland. | 5:30 |

| 1727 | Mary Jackson, a white woman, was executed for murder in Maryland. Hannah (George Walker), a black woman, was executed for an unknown reason in Virginia. Elizabeth Colson, a white woman, was executed for infanticide in Plymouth, Massachusetts. | 3:1 |

| 1728 | Sarah (Blair), a black woman, was executed for arson in Virginia. | 1:7 |

| 1729 | Babb (unknown), a black woman, was hanged for an unknown reason in Kent, Maryland. | 1:2 |

| 1732 | Ann Pettifer, a white woman, was hanged for spousal murder in North Carolina. An unnamed white woman was executed for murder in Pennsylvania. An unnamed black woman was hanged for participating in a “slave revolt” in New Orleans, Louisiana. | 3:2 |

| 1734 | An unnamed woman was executed for burglary in Chester, Pennsylvania. | 1:10 |

| 1747 | Elizabeth Wakefield, a white woman, was hanged for infanticide in Middlesex, Massachusetts. | 1:5 |

| 1748 | Bett (Wilhelmus Houghtaling), a black woman, was hanged for burglary in Kingston, New York. | 1:3 |

| 1749 | An unnamed black woman was executed for an unknown reason in Massachusetts. | 1:3 |

| 1756 | Plenty (Field), a black woman, was executed for poisoning in South Carolina. | 1:3 |

| 1758 | An unnamed black woman was executed for murder in Massachusetts. | 1:7 |

| 1773 | Fanny (Charlton), a black woman, was hanged for murder in Virginia. | 1:34 |

| 1776 | Two black women, Frances (Douglass) and one unnamed, were executed in Maryland for murder and arson (respectively). Also executed for arson, but in Virigina, was a black woman by the name of Synor (Downing). | 3:4 |

| 1782 | Judith (Crawford), a black woman, was hanged for arson in Maryland. | 1:16 |

| 1797 | Jenny (Haywood), a black woman, was hanged for murder in Robeson, North Carolina. Hannah McCay (Glare), a black woman, was executed for poisoning in Virginia. | 2:12 |

| 1823 | Two black women, Elizabeth Owens and Vina (Joseph Wynn), were executed in North Carolina for an unknown reason and child murder (respectively). | 2:21 |

| 1824 | Two black women, one unnamed (Roe) and Anaca (Ellis Palmer) were executed in South Carolina for murder and infanticide (respectively). In Kentucky, another unnamed black woman was executed for murder. | 3:38 |

| 1862 | Two black women, Carolina (Cobb) and Ann (Whittington), for unknown reasons, and another black woman, Ann (Clara), for murder, were executed in Louisiana. | 3:87 |

Notes. The ratios represent the resulting ratios of women to men. Bolded years contained neither executed men nor women according to the Espy file. Names in parentheses indicate the “slave owner” of the person executed. Most of the women in the table were first identified via Baker’s research and then verified using the Espy Papers (Espy, n.d.) [35].

References

- Death Penalty Information Center. Available online: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/ (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Death Penalty Information Center. Upcoming Executions. Available online: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/executions/upcoming-executions (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Federal Bureau of Investigations. Expanded Homicide Crime Statistics; Crime Data Explorer; 2023. Available online: https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/shr (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Death Penalty Information Center. Executions of Women. Available online: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/death-row/women/executions-of-women (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Burgess-Proctor, A. Intersections of race, class, gender, and crime: Future directions for feminist criminology. Fem. Criminol. 2006, 1, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney-Lind, M. Chivalry reexamined: Women and the criminal justice system. In Women, Crime, and the Criminal Justice System; Bowker, L., Ed.; D.C. Heath and Company: Lexington, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 197–223. [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt, J.W. Masculinities and Crime: Critique and Reconceptualization of Theory; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, P. Stories that kill: Masculinity and capital prosecutors’ closing arguments. Clevel. State Law Rev. 2023, 71, 1147–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Espy, M.W.; Smykla, J.O. Executions in the United States, 1608–2002: The Espy File; (ICPSR 8451) [Data set]; ICPSR: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, P.H.; McLaughlin, V. The Espy file on American executions: User beware. Homicide Stud. 2011, 15, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espy, M.W. Capital punishment and deterrence: What the statistics cannot show. Crime Delinq. 1980, 26, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought; Unwin Hyman: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics; Stanford University Press: Redwood, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- de Beauvoir, S. The Second Sex; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak, O. The Criminality of Women; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, W. Review of the criminality of women [Review of the book The Criminality of women, by O. Pollak]. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1951, 21, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scutt, J.A. The myth of the ‘chivalry factor’ in female crime. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 1979, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornicroft, K. Lawyers, gender and grievance arbitration outcomes. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1995, 8, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visher, C.A. Gender, police arrest decisions, and notions of chivalry. Criminology 1983, 21, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, M.D.; Curry, J.P.; Nelson-Kilger, S. Is chivalry dead? An analysis of changes in police dispositions of males and females. Criminology 1983, 21, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidensohn, F. Comparative models of policing and the role of women officers. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 1998, 1, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsich, E.A.; Richards, T.N.; Gover, A.R. A review of sex disparities in the “key players” of the capital punishment process: From defendants to jurors. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2014, 39, 732–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, A.E. A feminist look at the death penalty. Law Contemp. Probl. 2002, 65, 257–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, E.M. Gender bias in North Carolina’s death penalty. Duke J. Law Policy 2005, 12, 179–214. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, A. Unequal before the law: Men, women, and the death penalty. Am. Univ. J. Gend. Soc. Policy Law 2002, 8, 427–470. [Google Scholar]

- Streib, V. Gendering the death penalty: Countering sex bias in a masculine sanctuary. Ohio State Law J. 2002, 63, 433–474. [Google Scholar]

- Atwell, M.W. (Ed.) Wretched Sisters: Examining Gender and Capital Punishment; Peter Lang Press: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baerga-Santini, M.C. History and the contours of meaning: The abjection of Luisa Nevárez, first woman condemned to the gallows in Puerto Rico, 1905. Hisp. Am. Hist. Rev. 2009, 89, 643–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, A. Proof of Guilt: Barbara Graham and the Politics of Executing Women in America; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Philofsky, R. The lives and crimes of African American women on death row: A case study. Crime Law Soc. Change 2008, 49, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipman, M. The Penalty is Death: U.S. Newspaper Coverage of Women’s Executions; University of Missouri Press: Columbia, MO, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Streib, V. The Fairer Death: Executing Women in Ohio; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, C. Explaining gender neutrality in capital punishment research by way of a systematic review of studies citing the ‘Espy File’. Sexes 2024, 5, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschels, B. Data & the death penalty: Exploring the question of national consensus against executing emerging adults in conversation with Andrew Michael’s a decent proposal: Exempting eighteen-to-twenty-year-olds from the death penalty. N.Y.U. Rev. Law Soc. Change Harbinger 2016, 40, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- The Espy Papers. ME Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives; University at Albany, State University of New York: Albany, NY, USA, n.d.; Available online: https://archives.albany.edu/description/catalog/apap301 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- The Victor L. Streib Papers. ME Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives; University at Albany, State University of New York: Albany, NY, USA, n.d.; Available online: https://archives.albany.edu/description/catalog/apap330 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Streib, V. Rare and inconsistent: The death penalty. Fordham Urban Law J. 2006, 33, 609. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.V. Women and Capital Punishment in the United States: An Analytical History; McFarland & Company: Jefferson, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, D.A. Legal Executions in New England: A Comprehensive Reference, 1623–1960; McFarland & Co.: Jefferson, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Writers’ Project. Lucindy Allison was Interviewed by Miss Irene Robertson. Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 2, Arkansas, Part 1, Abbott-Byrd. November–December. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress. 1936. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn021/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Mather, C. Warnings from the Dead. Early Am. Work. Free. Libr. 1693, 665, 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Knight v. State. Southern Reporter Volume 92. 1922. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044103152757 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Davis, A. Reflections on the black woman’s role in the community of slaves. Black Sch. 1971, 3, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.M.; Hine, D.C. Gendered Resistance: Women, Slavery, and the Legacy of Margaret Garner; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide. Judged for More Than Her Crime: A Global Overview of Women Facing the Death Penalty. A Report of the Alice Project. Available online: https://dpw.lawschool.cornell.edu/publication/judged-more-than-her-crime/ (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- American Bar Association. Death Penalty Moratorium Resolution, MY 107. Available online: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/death_penalty_representation/dp-policy/1997_my_107.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Clune, L. Great importance world-wide: Presidential decision-making and the executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Am. Communist Hist. 2011, 10, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).