Effect of Victim Gender on Evaluations of Sexual Crime Victims and Perpetrators: Evidence from Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Legal Background in Japan

1.2. Social Background in Japan

1.3. Previous Studies on the Gender of Victims and Respondents

1.3.1. Victim’s Gender

1.3.2. Respondent’s Gender

1.3.3. Limitation of Existing Studies

1.4. Aim and Hypotheses

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Scenario

2.3. Procedure and Participants

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Victim/Perpetrator Blame

2.4.2. Negative Social Reactions

2.4.3. Sentencing Recommendation

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. ANOVAs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Ministry of Justice. White Paper on Crime 2023. 2023. Available online: https://hakusyo1.moj.go.jp/en/72/nfm/mokuji.html (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Johnson, D.T. Is rape a crime in Japan? Int. J. Asian Stud. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamon, Y. Revision of sexual offenses provisions: Draft outline. Ritsumeikan Hougaku 2023, 405/406, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring. Houmusho ‘Fudoui Seikou zai’ Heno Zaimei Henkou no Houshin ni Taisuru Spring no Kenkai ni Tsuite [Spring’s Position on the Ministry of Justice’s Policy of Changing the Name of the Crime to ’Non-Consensual Sexual Intercourse’]. 2023. Available online: http://spring-voice.org/news/statement230227/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Green, S. Criminalizing Sex: A Unified Liberal Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, S. Johnny Kitagawa’s Sexual Abuse: Japan’s Worst Kept Secret. BBC, 8 September 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-66752320 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Okubo, M.; Shimazaki, A. Ex-idol: Johnny’s apology over sex scandal an act of desperation. Asahi Shimbun, 15 May 2023. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14908268 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- 423 Victims of Sexual Abuse by Ex-Johnny’s Boss Receive Compensation; Total of 993 Claim Abuse by Late Johnny Kitagawa. The Japan Times, 15 June 2024. Available online: https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/society/general-news/20240615-192016/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- NHK. Johnny & Associates Admits Founder’s Abuse. 2023. Available online: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/backstories/2703/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Tang, F.; Sugiyama, S. Japan’s Top Talent Agency to Dissolve After Sex Abuse Scandal; over 300 Seek Damages. Reuters, 2 October 2023. Available online: https://jp.reuters.com/article/world/japans-top-talent-agency-to-dissolve-after-sex-abuse-scandal-over-300-seek-dam-idUSKCN3120GX/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Kaneko, K. Comedian Hitoshi Matsumoto’s Defamation Trial Kicks off. The Japan Times, 28 March 2024. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2024/03/28/japan/crime-legal/hitoshi-matsumoto-trial/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Takizawa, B.; Miyata, Y. Agency to Look into Abuse Claims Against Hitoshi Matsumoto. Asahi Shimbun, 25 January 2024. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15129619 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Inoue, Y. Comedian Hitoshi Matsumoto Sues Publisher over Sexual Assault Article. The Japan Times, 23 January 2024. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2024/01/23/japan/crime-legal/hitoshi-matsumoto-sues-bunshun/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Kanno, R. Japan Comedian Hitoshi Matsumoto to Drop Suit Against Publisher over Sex Scandal Report. The Mainichi, 8 November 2024. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20241108/p2a/00m/0et/016000c (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Comedian Matsumoto to Suspend Career due to Scandal. The Asahi Shinbun, 9 January 2024. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15106216 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Spring. Sei Higaishi no Jittai Chōsa Ankeeto Kekka Hōkokusho ③: Shitsuteki Bunseki Kekka Oyobi Kōsatsu [Report on the Results of a Survey on the Actual Situation of Sexual Victimization No. 3: Qualitative Analysis Results and Discussion]. Available online: http://spring-voice.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/アンケート分析報告書3.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Sommer, S.; Reynolds, J.J.; Kehn, A. Mock juror perceptions of rape victims: Impact of case characteristics and individual differences. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 2847–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.; Rogers, P.; Whiteleg, L. Effects of victim gender, victim sexual orientation, victim response and respondent gender on judgements of blame in a hypothetical adolescent rape. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2009, 14, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, G.L.; Cronin, J.M.; Steigman, H. Attributions of blame in sexual assault to perpetrators and victims of both genders. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2149–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catton, A.K.H.; Dorahy, M.J. Blame attributions against heterosexual male victims of sexual coercion: Effects of gender, social influence, and perceptions of distress. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP7014–NP7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Bruggen, M.; Grubb, A. A review of the literature relating to rape victim blaming: An analysis of the impact of observer and victim characteristics on attribution of blame in rape cases. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Pollard, P.; Archer, J. Effects of perpetrator gender and victim sexuality on blame toward male victims of sexual assault. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 146, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S.E. Social reactions, coping strategies, and self-blame attributions in adjustment to sexual assault. Psychol. Women Q. 1996, 20, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, C.M.; Pegel, G.A.; Johnson, A.B. Are survivors of sexual assault blamed more than victims of other crimes? J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, NP18394–NP18416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, E.; Bohner, G. Negative third-party reactions to male and female victims of rape: The influence of harm and normativity concerns. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP6055–NP6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socia, K.M.; Rydberg, J.; Dum, C.P. Punitive attitudes toward individuals convicted of sex offenses: A vignette study. Justice Q. 2021, 38, 1262–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatley, M.A.; Riggio, R.E. Gender differences in attributions of blame for male rape victims. J. Interpers. Violence 1993, 8, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I.; Lyons, A. The effect of victims’ social support on attributions of blame in female and male rape. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 1400–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömwall, L.A.; Landström, S.; Alfredsson, H. Perpetrator characteristics and blame attributions in a stranger rape situation. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2014, 6, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, M.C.; Gonçalves, G. Rape crimes reviewed: The role of observer variables in female victim blaming. Psychol. Thought 2015, 8, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockett, J.M.; Smith, S.J.; Klausing, C.D.; Saucier, D.A. Rape myth consistency and gender differences in perceiving rape victims: A meta-analysis. Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, A.K.; Mulder, E.; Pemberton, A.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M. Observer reactions to emotional victims of serious crimes: Stereotypes and expectancy violations. Psychol. Crime Law 2018, 24, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.W.; Scarduzio, J.A.; Lockwood Harris, K.; Carlyle, K.E.; Sheff, S.E. News stories of intimate Partner violence: An experimental examination of participant sex, perpetrator sex, and violence severity on seriousness, sympathy, and punishment preferences. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, J.H.; Simon, W. Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, W.; Gagnon, J.H. Sexual scripts. Society 1984, 22, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumann, E.O.; Paik, A.; Glasser, D.B.; Kang, J.H.; Wang, T.; Levinson, B.; Moreira, E.D.; Nicolosi, A.; Gingell, C. A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: Findings from the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2006, 35, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukai, T.; Pioch, C.; Sadamura, M.; Tozuka, K.; Fukushima, Y. Comparing attitudes toward sexual consent between Japan and Canada. Sexes 2024, 5, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, T.; Cho, E.; Matsuo, A.; Yuyama, Y.; Tanaka, Y. The relationship between attitudes toward sexual consent and perceived appropriateness of punishment: A comparison of Korea and Japan. Jpn. J. Pers. 2023, 32, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, N.; Tschanz, B.T. Rape perception differences between Japanese and American college students: On the mediating influence of gender role traditionality. Sex Roles 2005, 52, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, T.; Watamura, E. Comparing negative social reactions to sexual and non-sexual crimes: An experimental study with a Japanese Sample. Int. Criminol. 2022, 2, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, K. Chijin reipu higaisha ni taisuru daisansha no taido wo kitei suru youin: Taisho kanousei to kyoukan no yakuwari [Factors influencing third-party attitudes toward acquaintance rape victims: The role of perceived controllability and empathy]. Surugadai Daigaku Ronsou 2013, 48, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Omata, K. Factors affecting students’s perception of rape victims: Sex-role stereotype and the attitude toward rape. Jpn. J. Crim. Psychol. 2013, 51, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, Y.; Mori, T. The effect of the sexual orientation of male rape victims on the victim blaming from a third party. Jpn. J. Crim. Psychol. 2025, 62, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, T. Kaisei seihanzai shobatsu kitei no shimin ishiki to no tekigosei: Shitsumonshi deta ni motozuku jissho [The compatibility of the revised sexual offense punishment provisions with public attitudes: An empirical study based on questionnaire data]. Crim. Law J. 2024, 79, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfsson, K.; Strömwall, L.A.; Landström, S. Blame attributions in multiple perpetrator rape cases: The impact of sympathy, consent, force, and beliefs. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 5336–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullman, S.E. Psychometric characteristics of the social reactions questionnaire: A measure of reactions to sexual assault victims. Psychol. Women Q. 2000, 24, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 109, 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Locke, B.D.; Ludlow, L.H.; Diemer, M.A.; Scott, R.P.; Gottfried, M.; Freitas, G. Development of the conformity to masculine norms inventory. Psychol. Men Masc. 2003, 4, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, T.; Fukushima, Y.; Iriyama, S.; Aizawa, I. Modeling determinants of individual punitiveness in a late modern perspective: Data from Japan. Asian J. Criminol. 2021, 16, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirtenlehner, H.; Groß, E.; Meinert, J. Fremdenfeindlichkeit, Straflust und Furcht vor Kriminalität: Interdependenzen im Zeitalter spätmoderner Unsicherheit. Soz. Probl. 2016, 27, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.J.; Chouhy, C.; Lehmann, P.S.; Stevens, J.N.; Gertz, M. Economic anxieties, fear of crime, and punitive attitudes in Latin America. Punishm. Soc. 2020, 22, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | n | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Marital status | ||||||

| Woman | 410 | 54.8% | Married | 416 | 55.6% | ||

| Man | 338 | 45.2% | Single | 332 | 44.4% | ||

| Age | Parental status | ||||||

| 20s | 63 | 8.4% | With children | 381 | 50.9% | ||

| 30s | 91 | 12.2% | Without children | 367 | 49.1% | ||

| 40s | 129 | 17.2% | Household income | ||||

| 50s | 132 | 17.6% | <3 million yen | 241 | 32.2% | ||

| 60s | 123 | 16.4% | 3–5 million yen | 270 | 36.1% | ||

| 70s or older | 210 | 28.1% | ≥5 million yen | 237 | 31.7% | ||

| Victim Gender | Woman | Man | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent Gender | Woman (n = 197) | Man (n = 165) | Woman (n = 213) | Man (n = 173) | ||||||

| α | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Blame | ||||||||||

| Victim blame | 0.87 | 2.22 | 0.92 | 2.18 | 0.89 | 2.13 | 0.94 | 2.21 | 0.89 | |

| Perpetrator blame | 0.81 | 4.29 | 0.79 | 4.25 | 0.85 | 4.28 | 0.79 | 4.28 | 0.75 | |

| Negative social reactions | ||||||||||

| Stigma | 0.84 | 2.28 | 0.88 | 2.44 | 0.81 | 2.47 | 0.89 | 2.46 | 0.91 | |

| Distraction | 0.85 | 2.26 | 0.88 | 2.35 | 0.82 | 2.42 | 0.88 | 2.42 | 0.91 | |

| Take control | 0.63 | 2.54 | 0.73 | 2.57 | 0.73 | 2.45 | 0.72 | 2.54 | 0.73 | |

| Victim blame | 0.79 | 2.28 | 0.90 | 2.34 | 0.85 | 2.34 | 0.90 | 2.38 | 0.94 | |

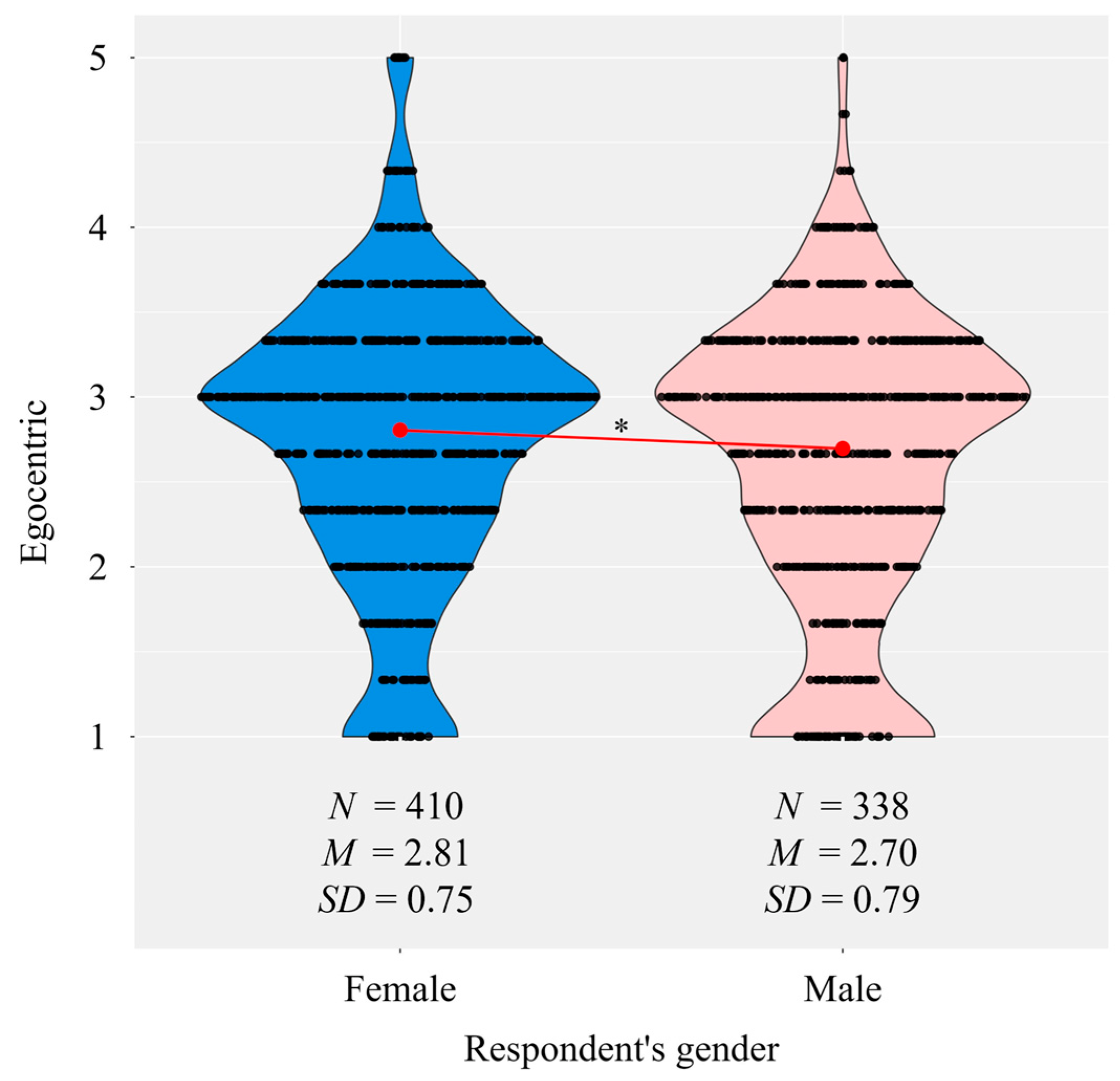

| Egocentric | 0.65 | 2.83 | 0.77 | 2.69 | 0.75 | 2.79 | 0.75 | 2.70 | 0.82 | |

| Intrusiveness | 0.85 | 2.66 | 0.92 | 2.58 | 0.91 | 2.51 | 0.95 | 2.65 | 0.91 | |

| Sentencing | ||||||||||

| Sentencing recommendation | ― | 8.98 | 15.39 | 8.73 | 13.57 | 10.00 | 13.32 | 8.26 | 9.10 | |

| Victim’s Gender | Respondent’s Gender | Interaction | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |||||

| Blame | ||||||||||

| Victim blame | 0.30 | <0.01 | 0.59 | 0.09 | <0.01 | 0.77 | 0.83 | <0.01 | 0.36 | |

| Perpetrator blame | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.88 | 0.18 | <0.01 | 0.67 | 0.17 | <0.01 | 0.68 | |

| Negative social reactions | ||||||||||

| Stigma | 2.73 | <0.01 | 0.10 | 1.33 | <0.01 | 0.25 | 1.64 | <0.01 | 0.20 | |

| Distraction | 3.47 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.41 | <0.01 | 0.52 | 0.50 | <0.01 | 0.48 | |

| Take control | 1.29 | <0.01 | 0.26 | 1.19 | <0.01 | 0.28 | 0.22 | <0.01 | 0.64 | |

| Victim blame | 0.51 | <0.01 | 0.47 | 0.55 | <0.01 | 0.46 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.87 | |

| Egocentric | 0.05 | <0.01 | 0.83 | 4.39 | <0.01 | 0.04 * | 0.22 | <0.01 | 0.64 | |

| Intrusiveness | 0.34 | <0.01 | 0.56 | 0.18 | <0.01 | 0.68 | 2.39 | <0.01 | 0.12 | |

| Sentencing | ||||||||||

| Original | 0.08 | <0.01 | 0.77 | 1.07 | <0.01 | 0.30 | 0.59 | <0.01 | 0.44 | |

| Excluding > 30 years | 7.75 | 0.01 | 0.01 ** | 0.60 | <0.01 | 0.44 | 0.95 | <0.01 | 0.33 | |

| Excluding + 2SD | 4.43 | <0.01 | 0.04 * | 0.49 | <0.01 | 0.49 | 0.97 | <0.01 | 0.32 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mukai, T. Effect of Victim Gender on Evaluations of Sexual Crime Victims and Perpetrators: Evidence from Japan. Sexes 2025, 6, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020018

Mukai T. Effect of Victim Gender on Evaluations of Sexual Crime Victims and Perpetrators: Evidence from Japan. Sexes. 2025; 6(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukai, Tomoya. 2025. "Effect of Victim Gender on Evaluations of Sexual Crime Victims and Perpetrators: Evidence from Japan" Sexes 6, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020018

APA StyleMukai, T. (2025). Effect of Victim Gender on Evaluations of Sexual Crime Victims and Perpetrators: Evidence from Japan. Sexes, 6(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020018