The Evaluation of Psychosexual Profiles in Dominant and Submissive BDSM Practitioners: A Bayesian Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

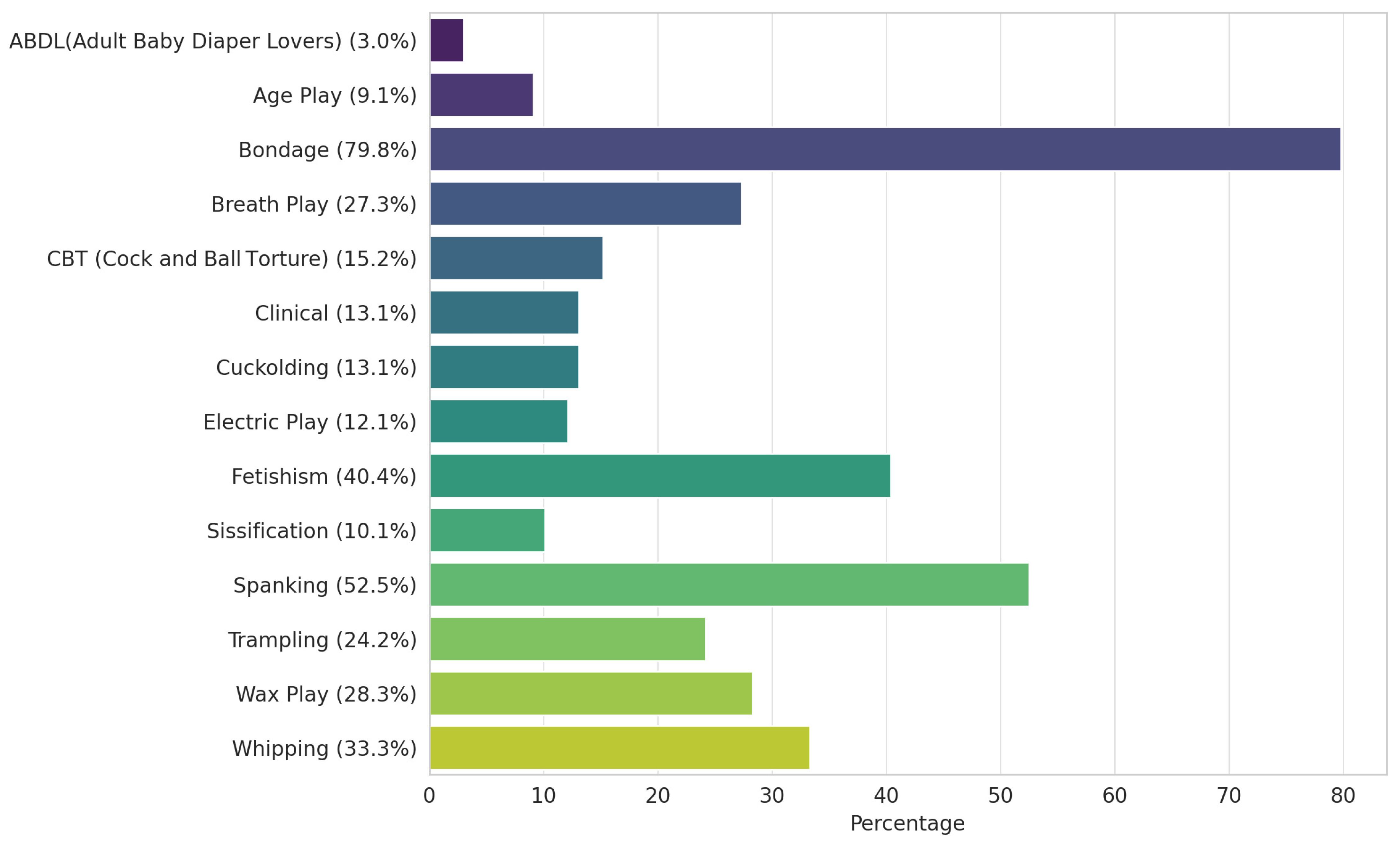

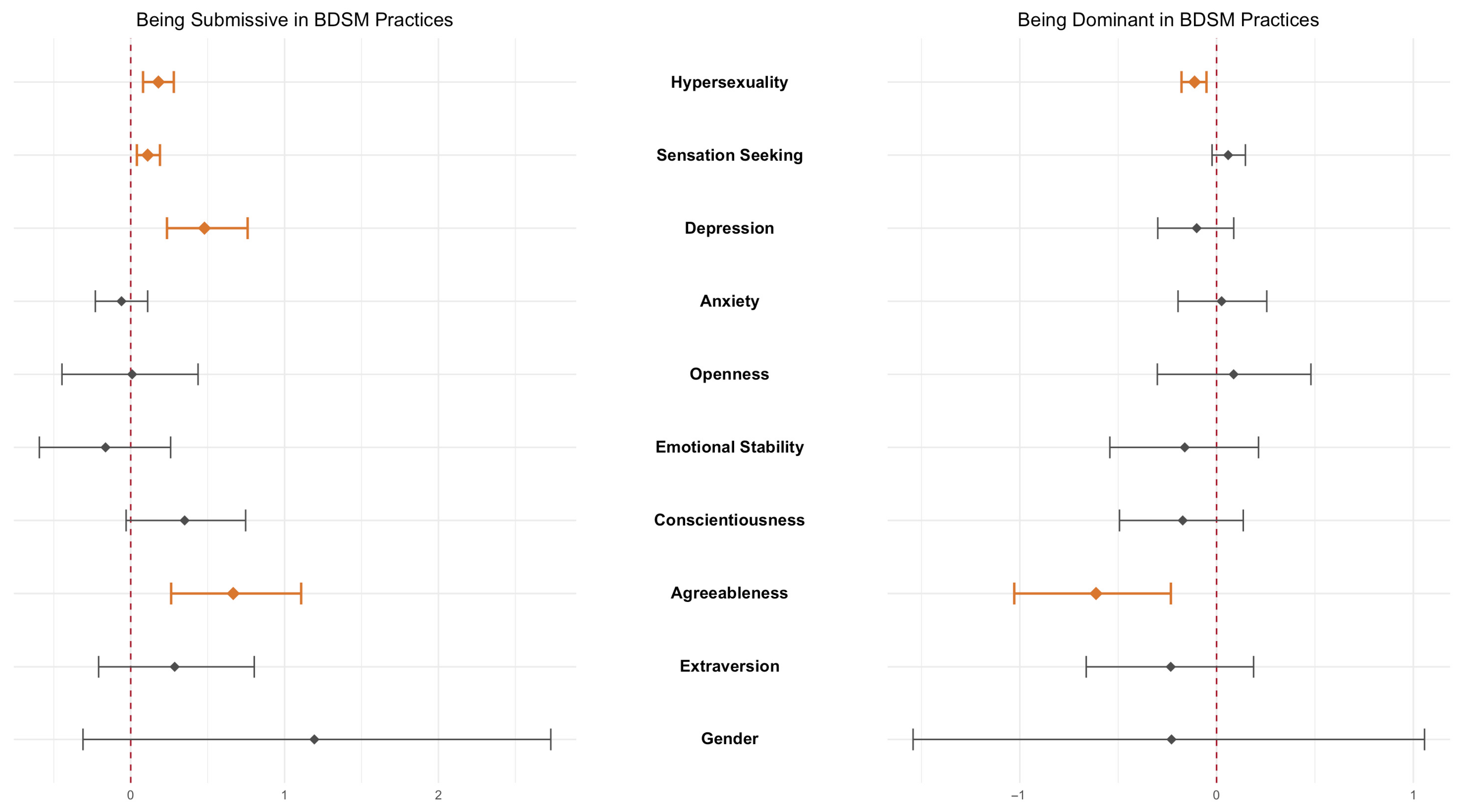

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Neef, N.; Coppens, V.; Huys, W.; Morrens, M. Bondage-Discipline, Dominance-Submission and Sadomasochism (BDSM) From an Integrative Biopsychosocial Perspective: A Systematic Review. Sex. Med. 2019, 7, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limoncin, E.; Carta, R.; Gravina, G.L.; Carosa, E.; Ciocca, G.; Di Sante, S.; Isidori, A.M.; Lenzi, A.; Jannini, E.A. The Sexual Attraction toward Disabilities: A Preliminary Internet-Based Study. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2014, 26, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enquist, M.; Aronsson, H.; Ghirlanda, S.; Jansson, L.; Jannini, E.A. Exposure to Mother’s Pregnancy and Lactation in Infancy Is Associated with Sexual Attraction to Pregnancy and Lactation in Adulthood. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorolli, C.; Ghirlanda, S.; Enquist, M.; Zattoni, S.; Jannini, E.A. Relative Prevalence of Different Fetishes. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2007, 19, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, P.H. Psychological Functioning of Bondage/Domination/Sado-Masochism (BDSM) Practitioners. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 2006, 18, 79–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, K. BDSM Role Fluidity: A Mixed-Methods Approach to Investigating Switches Within Dominant/Submissive Binaries. J. Homosex. 2018, 65, 1299–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyal, C.C. Defining “Normophilic” and “Paraphilic” Sexual Fantasies in a Population-Based Sample: On the Importance of Considering Subgroups. Sex. Med. 2015, 3, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wismeijer, A.A.J.; van Assen, M.A.L.M. Psychological Characteristics of BDSM Practitioners. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 1943–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paarnio, M.; Sandman, N.; Källström, M.; Johansson, A.; Jern, P. The Prevalence of BDSM in Finland and the Association between BDSM Interest and Personality Traits. J. Sex. Res. 2023, 60, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.J.; Bannerman, B.A.; Lalumière, M.L. Paraphilic Interests. Sex. Abus. 2016, 28, 20–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simula, B.L.; Sumerau, J. The Use of Gender in the Interpretation of BDSM. Sexualities 2019, 22, 452–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro Pascoal, P.; Cardoso, D.; Henriques, R. Sexual Satisfaction and Distress in Sexual Functioning in a Sample of the BDSM Community: A Comparison Study Between BDSM and Non-BDSM Contexts. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roush, J.F.; Brown, S.L.; Mitchell, S.M.; Cukrowicz, K.C. Shame, Guilt, and Suicide Ideation among Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, and Sadomasochism Practitioners: Examining the Role of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2017, 47, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, A.; Weaver, A. An Examination of Personality Characteristics Associated with BDSM Orientations. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2014, 23, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.; Barker, E.D.; Rahman, Q. A Systematic Scoping Review of the Prevalence, Etiological, Psychological, and Interpersonal Factors Associated with BDSM. J. Sex. Res. 2020, 57, 781–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.L.; Fried, A.L.; Chamberlain, J. An Examination of Empathy and Interpersonal Dominance in BDSM Practitioners. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuerwegen, A.; Huys, W.; Coppens, V.; De Neef, N.; Henckens, J.; Goethals, K.; Morrens, M. The Psychology of Kink: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study Investigating the Roles of Sensation Seeking and Coping Style in BDSM-Related Interests. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Nimbi, F.; Limoncin, E.; Mollaioli, D.; Marchetti, D.; Verrocchio, M.C.; Simonelli, C.; Jannini, E.; Fontanesi, L. Italian Validation of the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (HBI): Psychometric Characteristics of a Self-Report Tool Evaluating a Psychopathological Facet of Sexual Behavior. J. Psychopathol. 2020, 26, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Di Stefano, R.; Collazzoni, A.; Jannini, T.B.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Jannini, E.A.; Rossi, A.; Rossi, R. Sexual Dysfunctions and Problematic Sexuality in Personality Disorders and Pathological Personality Traits: A Systematic Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, K.R.; Sagarin, B.J.; Lee, E.M. Participating in a Culture of Consent May Be Associated With Lower Rape-Supportive Beliefs. J. Sex. Res. 2017, 54, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogak, H.M.E.; Connor, J.J. Practice of Consensual BDSM and Relationship Satisfaction. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2018, 33, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, R.; South, M.; Carpenter, B.N.; Hardy, S.A. The Roles of Shame and Guilt in Hypersexual Behavior. Sex. Addict. Compulsivity 2011, 18, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santtila, P.; Sandnabba, N.K.; Alison, L.; Nordling, N. Investigating the Underlying Structure in Sadomasochistically Oriented Behavior. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2002, 31, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzenda, W. Informative Versus Non-Informative Prior Distributions and Their Impact on the Accuracy of Bayesian Inference. Stat. Transition. New Ser. 2016, 17, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Measuring Personality in One Minute or Less: A 10-Item Short Version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J. Res. Pers. 2007, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, G.; Peluso, A.M.; Capestro, M.; Miglietta, M. An Italian Version of the 10-Item Big Five Inventory: An Application to Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Values. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L. Validation and Utility of a Self-Report Version of PRIME-MD. The PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA 1999, 282, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbody, S.; Richards, D.; Barkham, M. Diagnosing Depression in Primary Care Using Self-Completed Instruments: UK Validation of PHQ-9 and CORE-OM. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2007, 57, 650–652. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkbrenner, M.T.; Ryan, A.F.; Hunt, A.J.; Rahman, S.R. Internal Consistency Reliability and Internal Structure Validity of the English Versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7: A Psychometric Synthesis. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2023, 56, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotti, E.; Fassone, G.; Picardi, A.; Sagoni, E.; Ramieri, L.; Lega, I.; Camaioni, D.; Abeni, D.; Pasquini, P. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) for the Screening of Psychiatric Disorders: A Validation Study versus the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I (SCID-I). Ital. J. Psychopathol. 2003, 9, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolgeo, T.; Di Matteo, R.; Simonelli, N.; Dal Molin, A.; Lusignani, M.; Bassola, B.; Vellone, E.; Maconi, A.; Iovino, P. Psychometric Properties and Measurement Invariance of the 7-Item General Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) in an Italian Coronary Heart Disease Population. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 334, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, R.C.; Li, D.S.; Gilliland, R.; Stein, J.A.; Fong, T. Reliability, Validity, and Psychometric Development of the Pornography Consumption Inventory in a Sample of Hypersexual Men. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2011, 37, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.C.; Carpenter, B.N. Exploring Relationships of Psychopathology in Hypersexual Patients Using the MMPI-2. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2009, 35, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H.; Stephenson, M.T.; Palmgreen, P.; Lorch, E.P.; Donohew, R.L. Reliability and Validity of a Brief Measure of Sensation Seeking. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002, 32, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, M.S. Sensation Seeking: Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Litvin, S.W. Sensation Seeking and Its Measurement for Tourism Research. J. Travel. Res. 2008, 46, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primi, C.; Narducci, R.; Benedetti, D.; Donati, M.; Chiesi, F. Validity and Reliability of the Italian Version of the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS) and Its Invariance across Age and Gender. TPM-Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 18, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruschke, J.K.; Liddell, T.M. The Bayesian New Statistics: Hypothesis Testing, Estimation, Meta-Analysis, and Power Analysis from a Bayesian Perspective. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2018, 25, 178–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bujkiewicz, S.; Jackson, D. Three New Methodologies for Calculating the Effective Sample Size When Performing Population Adjustment. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehtari, A.; Gelman, A.; Simpson, D.; Carpenter, B.; Bürkner, P.-C. Rank-Normalization, Folding, and Localization: An Improved R-hat for Assessing Convergence of MCMC. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1903.08008. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys, H. The Theory of Probability, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.D.; Wagenmakers, E.-J. Bayesian Cognitive Modeling; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781107603578. [Google Scholar]

- Westfall, P.; Johnson, W.O.; Utts, J. A Bayesian Perspective on the Bonferroni Adjustment. Biometrika 1997, 84, 419–427. [Google Scholar]

- The jamovi Project. jamovi (Version 2.6) [Computer Software]. 2025. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Rouder BayesFactor: Computation of Bayes Factors for Common Designs; 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/BayesFactor/BayesFactor.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Bürkner, P.-C. Advanced Bayesian Multilevel Modeling with the R Package Brms. R J. 2018, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P. The Five-Factor Model In Personality: A Critical Appraisal. J. Pers. 1992, 60, 329–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Zhang, X. Empathy in Female Submissive BDSM Practitioners. Neuropsychologia 2018, 116, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Fontanesi, L.; Robilotta, A.; Limoncin, E.; Nimbi, F.M.; Mollaioli, D.; Sansone, A.; Colonnello, E.; Simonelli, C.; Di Lorenzo, G.; et al. Hypersexual Behavior and Depression Symptoms among Dating App Users. Sexes 2022, 3, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Pelligrini, F.; Mollaioli, D.; Limoncin, E.; Sansone, A.; Colonnello, E.; Jannini, E.A.; Fontanesi, L. Hypersexual Behavior and Attachment Styles in a Non-Clinical Sample: The Mediation Role of Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, G.; Longo, L.; Jannini, T.B.; Niolu, C.; Rossi, R.; Siracusano, A. Oxytocin in the Prevention and the Treatment of Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Psychopathol. 2020, 26, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mollaioli, D.; Sansone, A.; Ciocca, G.; Limoncin, E.; Colonnello, E.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Jannini, E.A. Benefits of Sexual Activity on Psychological, Relational, and Sexual Health During the COVID-19 Breakout. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, D.A. Hypersexuality: Fact or Fiction? J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozifkova, E.; Kolackova, M. Sexual Arousal by Dominance and Submission in Relation to Increased Reproductive Success in the General Population. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2017, 38, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Young, C.M.; Neighbors, C.; DiBello, A.M.; Traylor, Z.K.; Tomkins, M. Shame and Guilt-Proneness as Mediators of Associations Between General Causality Orientations and Depressive Symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 35, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öngen, D.E. The Relationships between Self-Criticism, Submissive Behavior and Depression among Turkish Adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, S.; Jouvent, R.; Bungener, C.; Widlöcher, D. Sensation Seeking and Depressive Mood. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1992, 13, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshel, N.; Roiser, J.P. Reward and Punishment Processing in Depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimón, J.; Las Hayas, C.; Guillén, V.; Boyra, A.; González-Pinto, A. Shame, Sensitivity to Punishment and Psychiatric Disorders. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2007, 21, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Limoncin, E.; Lingiardi, V.; Burri, A.; Jannini, E.A. Response Regarding Existential Issues in Sexual Medicine: The Relation Between Death Anxiety and Hypersexuality. Sex. Med. Rev. 2018, 6, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Sample | Dominants | Submissive | Switch | BF10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender a | Male | 60 (60%) | 33 (78.5%) | 20 (55.6%) | 7 (33.3%) | 47.26 |

| Female | 39 (40%) | 9 (21.5%) | 16 (44.4%) | 14 (66.7%) | ||

| Age b | 31.4 ± 11.4 | 29.6 ± 11.12 | 32.2 ± 12.61 | 33.7 ± 9.5 | 0.22 | |

| Sexual Orientation a | Heterosexual | 71 (71.7%) | 33 (78.6%) | 28 (77.8%) | 10 (47.6%) | 3.34 |

| Non-heterosexual | 29 (28.3%) | 9 (21.4%) | 8 (22.2%) | 11 (52.4%) | ||

| Relational Status a | Single | 53 (53.5%) | 24 (57.1%) | 25 (69.5%) | 4 (19.1%) | 3.69 |

| Engaged | 36 (36.4%) | 16 (38.1%) | 7 (19.4%) | 13 (61.8%) | ||

| Married | 10 (10.1%) | 2 (4.8%) | 4 (11.1%) | 4 (19.1%) | ||

| N° of sex partners b | 2.24 ± 2.72 | 1.77 ± 2.12 | 2.81 ± 3.21 | 2.81 ± 2.60 | 0.92 |

| Variable | Test | Sample | Dominants | Submissive | Switch | BF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | PHQ-9 | 7.28 ± 5.61 | 4.93 ± 4.58 | 9.03 ± 5.30 | 9.00 ± 6.45 | 31.08 |

| Anxiety | GAD-7 | 5.99 ± 4.67 | 4.64 ± 4.42 | 7.25 ± 4.39 | 6.52 ± 5.11 | 1.47 |

| Extraversion | BFI-10 | 6.25 ± 1.53 | 6.21 ± 1.22 | 6.33 ± 1.60 | 6.19 ± 1.96 | 0.10 |

| Neuroticism | BFI-10 | 6.19 ± 1.78 | 6.50 ± 1.71 | 6.06 ± 1.47 | 5.58 ± 2.31 | 0.26 |

| Openness | BFI-10 | 7.25 ± 1.76 | 7.09 ± 1.68 | 7.53 ± 1.78 | 8.38 ± 1.63 | 2.08 |

| Agreebleness | BFI-10 | 5.71 ± 1.56 | 5.42 ± 1.29 | 6.09 ± 1.49 | 5.62 ± 2.06 | 0.41 |

| Conscientiousness | BFI-10 | 6.93 ± 1.70 | 6.71 ± 1.53 | 7.06 ± 1.79 | 7.14 ± 1.90 | 0.16 |

| Hypersexuality | HBI-19 | 39.28 ± 12.92 | 32.67 ± 11.14 | 45.39 ± 12.44 | 42.05 ± 11.21 | 1448.60 |

| Sensation Seeking | BSSS-8 | 23.27 ± 8.78 | 19.90 ± 8.83 | 23.78 ± 8.41 | 29.14 ± 5.80 | 106.67 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | Prior Odds | Posterior Odds | BF10, U | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submissive | vs | Switch | 0.587 | 0.162 | 0.28 |

| vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 34.875 | 59.38 | |

| Switch | vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 4.565 | 7.77 |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | Prior Odds | Posterior Odds | BF10, U | ||

| Submissive | vs | Switch | 0.587 | 0.185 | 0.31 |

| vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 2.439 | 4.15 | |

| Switch | vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 0.407 | 0.69 |

| Hypersexuality (HBI-19) | Prior Odds | Posterior Odds | BF10, U | ||

| Submissive | vs | Switch | 0.587 | 0.248 | 0.42 |

| vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 1117.187 | 1901.92 | |

| Switch | vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 8.249 | 14.04 |

| Sensation Seeking (BSSS-8) | Prior Odds | Posterior Odds | BF10, U | ||

| Submissive | vs | Switch | 0.587 | 2.353 | 4.01 |

| vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 0.731 | 1.24 | |

| Switch | vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 216.713 | 368.93 |

| Openness (BFI-10) | Prior Odds | Posterior Odds | BF10, U | ||

| Submissive | vs | Switch | 0.587 | 0.608 | 1.03 |

| vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 0.234 | 0.40 | |

| Switch | vs | Dominant | 0.587 | 4.621 | 7.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mollaioli, D.; Jannini, T.B.; Piga Malaianu, D.; Sansone, A.; Colonnello, E.; Limoncin, E.; Ciocca, G.; Jannini, E.A. The Evaluation of Psychosexual Profiles in Dominant and Submissive BDSM Practitioners: A Bayesian Approach. Sexes 2025, 6, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020016

Mollaioli D, Jannini TB, Piga Malaianu D, Sansone A, Colonnello E, Limoncin E, Ciocca G, Jannini EA. The Evaluation of Psychosexual Profiles in Dominant and Submissive BDSM Practitioners: A Bayesian Approach. Sexes. 2025; 6(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMollaioli, Daniele, Tommaso B. Jannini, Diana Piga Malaianu, Andrea Sansone, Elena Colonnello, Erika Limoncin, Giacomo Ciocca, and Emmanuele A. Jannini. 2025. "The Evaluation of Psychosexual Profiles in Dominant and Submissive BDSM Practitioners: A Bayesian Approach" Sexes 6, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020016

APA StyleMollaioli, D., Jannini, T. B., Piga Malaianu, D., Sansone, A., Colonnello, E., Limoncin, E., Ciocca, G., & Jannini, E. A. (2025). The Evaluation of Psychosexual Profiles in Dominant and Submissive BDSM Practitioners: A Bayesian Approach. Sexes, 6(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020016