1. Introduction

Child abuse refers to the act of subjecting the individual under one’s care, custody, or supervision to various forms of violence, including neglect; deprivation; abandonment; exploitation; excessive labor; and physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. In Brazil, child abuse is considered a criminal offense under Article 136 of the Penal Code (Decree-Law N°. 2848, 1940; Law N°. 8069, 1990; Law N°. 13,010, 2014). According to the World Health Organization [

1], child abuse encompasses any form of mistreatment, neglect, exploitation, or harm inflicted on children and adolescents between the ages of 0 and 18.

These acts can result in potential or actual harm to a child’s survival, development, health, and dignity and typically occur within relationships of responsibility, trust, or power.

Negative experiences, such as abuse and neglect, that occur during early childhood can have profound effects on the developing brain and a child's overall well-being. These adverse events can trigger the release of stress mediators and neurotransmitters, which interact with developing neurons and may cause structural and functional changes. As a result, cognitive, emotional, and physical developmental processes can be significantly affected.

The vulnerability and long-term consequences of maltreatment are particularly pronounced during this critical phase of development. It is important to note that the maturation of the nervous system continues through late adolescence, making early childhood a crucial period for neural growth and organization. The damage that occurs during this period can have lasting effects on the person, with repercussions on their self-esteem and interpersonal relationships [

2,

3,

4].

In 2021, Brazil witnessed a distressing reality, with approximately 45,076 cases of sexual violence reported among children and adolescents aged 0 to 17 years. This heinous crime remains the most prevalent form of violence against children in the country. The statistics from the Brazilian Forum of Public Security (BFPS) [

5] reveal that children aged 5 to 9 years were the main victims, with a rate of 86.6 victims per 100 thousand, followed by pre-adolescents aged 10 to 14 years, with a rate of 173.1 victims per 100 thousand (

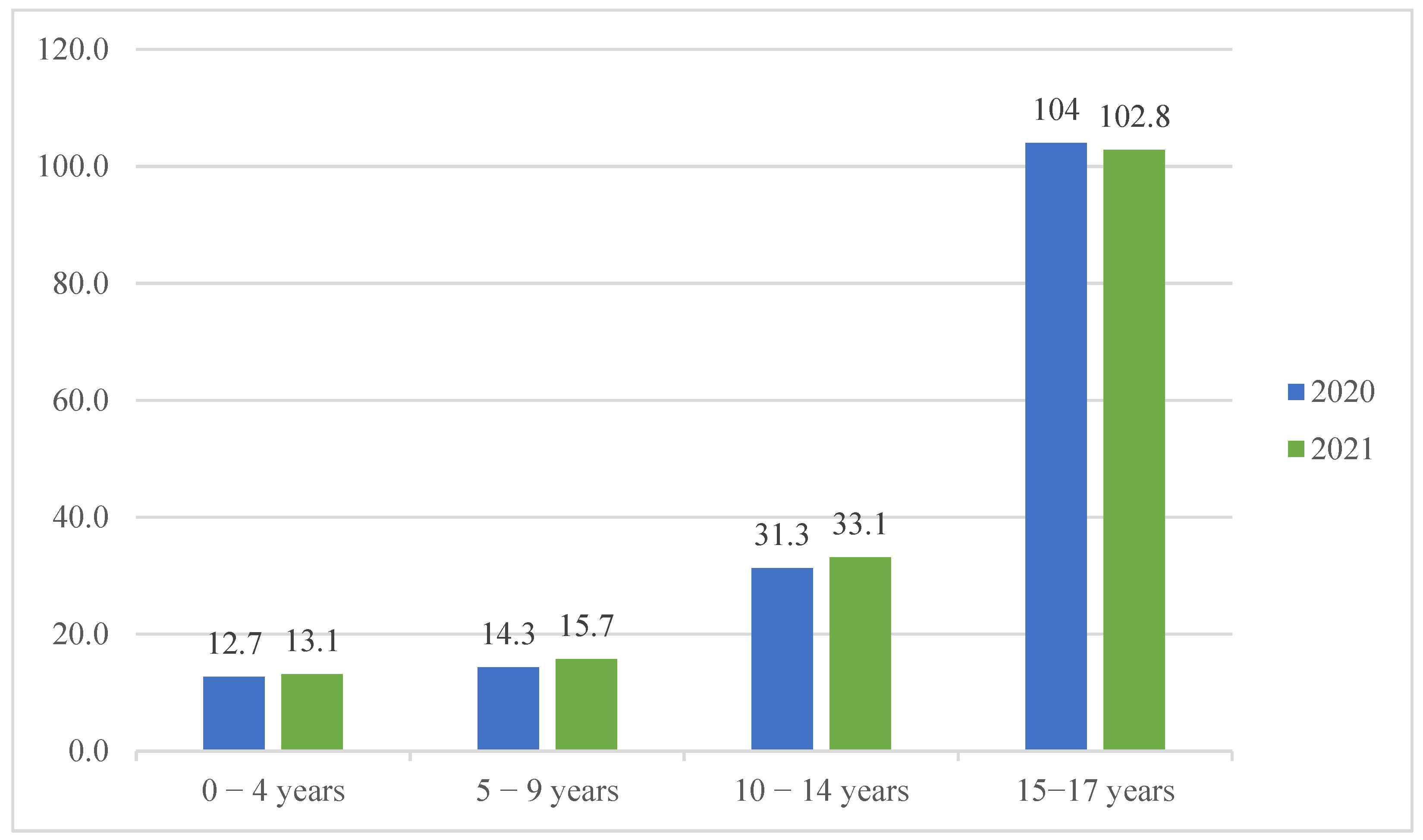

Table 1). Other forms of violence are also widely committed. The rates of the records of bodily injuries in the context of domestic violence, organized by age group, can be seen in

Figure 1.

Unfortunately, this issue is not exclusive to Brazil. A global study conducted in 96 countries estimated that over 50% of children and adolescents worldwide experienced some form of physical, psychological, or sexual violence between 2015 and 2016 [

6].

The prevalence of violence against children in Brazil is alarming, as the country holds the highest estimated rate of child abuse in the world. Shockingly, 70% of these violent acts occur within the victim’s or suspect’s own home, and a staggering 63.2% of these cases are committed by the child’s own parents. It is crucial to recognize that 56.2% of the victims are girls, but it is equally important to acknowledge that 40.5% are boys. Although often overlooked, sexual violence against boys remains a significant issue. Disturbingly, approximately 363,803 (13.6%) female children and adolescents gave birth to live-born babies in 2021. Furthermore, in 2019 alone, there were 20,000 marriages involving children under the age of 18 in the country [

7,

8,

9].

Childhood trauma, as described by Biasuz and Böeckel (2012) [

10], occurs when a child’s innate resources are violated by distressing events. Particularly, when experienced in early childhood, these traumas are associated with negative or maladaptive consequences that impair the individual’s capacity for emotional regulation by not developing the necessary skills to respond appropriately to such situations.

The research by Bergamo (2007) [

11] indicates that children who experience abuse during their early years tend to form insecure attachments to their caregivers. This, in turn, can lead to low self-esteem, aggressive and impulsive behaviors, depressive symptoms, and difficulties in forming healthy relationships with peers. An insufficient social skill repertoire is often linked to the development of psychological disorders in adulthood, significantly impacting an individual’s mental well-being [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

According to Wamboldt and Reiss (2006 [

17], as cited in Biel, 2018 [

18], p. 3), children who are raised by parents with psychiatric disorders face an increased risk of developing mental health symptoms. This risk is influenced not only by genetic factors but also by the challenges associated with dysfunctional caregiving and the parents’ difficulties in providing a nurturing family environment. Consequently, when childhood trauma is linked to a family history of mood disorders, there is a stronger correlation with the development of such symptoms in adulthood and a higher likelihood of future instances of neglecting one's own offspring [

18]. This devastating cycle ultimately contributes to further public health problems [

19].

The studies conducted by Weil et al. (2004) [

20] reveal that traumatic psychosocial environments during childhood serve as risk factors for various psychiatric syndromes in adulthood. Among individuals with affective disorders, 57.1% reported experiencing one or more types of traumatic events during their childhood. These events include physical punishment (28.7%), traumatic parental separation (27.1%), exposure to alcohol and drug use by adults in the household (22%), and the presence of family violence (22%).

Citing the study conducted by Goldberg et al. (2005) [

21], Daruy-Filho et al. (2013) [

22] highlight that traumatic experiences in childhood are recognized as common events in individuals with bipolar disorder, with 49% reporting some form of abuse or neglect. In research carried out on women diagnosed with bipolar disorder, clear reports of physical abuse (B = 0.64,

p ≤ 0.01) and emotional abuse (B = 0.44,

p = 0.01) were associated with the use of maladaptive strategies. Of these women, 46% avoided emotionally distressing trauma-related stimuli, and 33% reported difficulty in seeking social support.

Emotional abuse and neglect have been found to have a strong association with the development of bipolar disorder. It is important to note that the earlier the individual is exposed to trauma, the greater their vulnerability to developing bipolar disorder, and the more severe their clinical course may be. This can include a higher number of episodes, rapid cycling, an increased incidence of substance abuse, and higher rates of suicide attempts.

A study indicated that 57.3% of its participants had experienced childhood maltreatment, which included physical abuse, psychological abuse, and neglect. Furthermore, the study revealed that mothers with mental disorders who experienced manic and depressive episodes faced challenges in expressing affection and providing adequate care for their children. This conflicting environment not only accelerates the onset of symptoms in children, but it also leads to difficulties in socialization and contributes to an unstable adulthood [

18].

Science has presented quantitative and statistical studies on child abuse and a limited number of studies that have investigated the consequences and long-term impacts on the lives of individuals who suffered abuse in childhood and did not have access to public policies, forms of protection, or social support after identifying child abuse, mainly in Brazil. In addition to the very rare qualitative studies which seek the report or the life story of victims of child abuse, this qualitative study is ideographic in nature and aims to assess the “particular” form of the repercussions of abuse in the life of a 60-year-old woman, who became vulnerable to a series of relational, social, and economic problems due to her exposure to traumatic events in her childhood without access to a social support network, therefore giving voice to this victim of child abuse through the process of the investigation and complex analysis of her life history and family relationships as well as through a mental status examination and active listening.

Thus, we present a clinical case of the exposure to traumatic events and sexual abuse in childhood of someone who did not receive adequate care and whose consequences resulted in serious repercussions on their mental health and interpersonal relationships, marriage and motherhood in adolescence, the repetition of family behaviors (the abandonment of children), low self-esteem, self-injury, suicide attempts, violent relationships, economic/financial vulnerability, and the lack of health care, evolving into bipolar disorder and influences on their personality (dependent personality traits and borderline personality traits). In view of this, it is essential to emphasize the importance of protective measures and the need for research dedicated to this topic.

2. Patient Overview

Maria, a 60-year-old woman and former compulsive smoker, has a varied medical history, including high blood pressure and rheumatoid arthritis. She recently suffered a stroke. Maria reports a previous diagnosis of bipolar disorder and psychiatric treatment that was interrupted several times, claiming financial difficulties in covering her medical expenses (appointments and medication). Therefore, she would ween off the medication, randomly cutting her intake and compromising her medical treatment. Until the age of eight, she lived with her parents and siblings in a rigid, abusive, and violent environment that involved physical punishments practiced by her father. After her parents’ separation, her mother, herself, and one of her brothers (who was diagnosed with schizophrenia) moved in with their maternal grandmother. Eventually, her mother moved abroad and left Maria under the care of her grandmother, who was a pianist and music teacher. Maria developed a love for the arts through spending time with her grandmother. Her family has a history of mental disorders.

She reports episodes of childhood sexual abuse that she does not remember clearly. Despite contracting a sexually transmitted disease, her family denied the abuse. Maria reports that, as a teenager, she began to self-harm and attempt suicide. These facts were neglected and interpreted by her family as cries for attention due to her mother’s absence. At the age of 14, she married a religious young man (18 years old) with whom she had four children. They had a tumultuous relationship with several separations, leading to divorce following her infidelity. After the divorce, she was assigned as the children’s guardian but later lost custody due to her constant mood swings. This situation resulted in more than forty years without contact with her children and caused her much regret and suffering.

After some time, Maria resumed her studies and became involved in another abusive relationship characterized by physical, sexual, and psychological violence, which lasted for three years. Subsequently, she entered another relationship and adopted a child. Currently, she defines this relationship as cohabitation between two colleagues sharing a home, although her account indicates the presence of psychological and financial abuse. Despite attempting to support her adopted child in their goals, she claims they do not have a harmonious relationship. Maria reports having graduated twice and having a postgraduate degree, but she is financially dependent on her family, as she is unemployed. She reports dedicating part of her time to studies and poetry and to volunteer work in a non-governmental organization that supports vulnerable girls.

During the interview, Maria appeared absent at times, as if she did not perceive external stimuli, requiring certain questions to be repeated. There were indications of alterations in remote memory, as she struggled to recall significant events in her life history, such as childhood sexual abuse. Additionally, she displayed slow thinking and acceleration when discussing negative past experiences. Excessive concern about her mental health, including suicidal ideation, was observed, although no delusions, obsessions, or hallucinations were identified. In terms of language, she expressed herself coherently and articulately. However, her voice exhibited a constant volume and slow rhythm accompanied by limited facial and body expressions. Maria displays high intellectual performance.

Furthermore, there were noticeable alterations in her affectivity, such as depressed mood, low self-esteem, and a lack of interest in life. Despite having a good network of friends, she complains that people do not show empathy towards her. Maria lacks an effective family support network, experiencing unstable, abusive, or severed relationships, which she associates with her mood swings and episodes of remitted mania. She expresses feelings of loneliness, emotional blunting, and a lack of emotional affection, leading to introverted behavior and apathy towards social and sexual contact.

Regarding personality, Maria has little openness to new experiences, low conscientiousness with little planning and self-discipline, high introspection, emotional instability with depressed mood, emotional dependence, and high vulnerability. However, she demonstrates pleasant traits, including helpfulness, generosity, and respectfulness.

3. Method

This study, through qualitative research, sought to give voice to a woman who, during her childhood and adolescence, was the victim of a series of abuses (neglect, physical punishment, emotional and sexual abuse, and abandonment). Science has presented quantitative studies with the theme of child abuse but has very rarely presented qualitative studies which seek the report and the history of victims of abuse. This study has an idiosyncratic character, as it aimed to assess the “particular“ form of repercussions of abuse in the life of a 60-year-old woman.

Psychological assessment consisted of a scientific process of investigation which sought answers to a specific demand using psychological methods and techniques, such as interviews, observation, the subject’s life history, games, dynamics, mental state examination, psychological tests, and scales, among other sources. This investigation process had to consider the influences of the social, economic, and cultural contexts in addition to the biological and hereditary aspects of the subject. Therefore, the psychological assessment was not limited to psychological tests and had a dynamic character, as its results could be influenced by multi-factorial aspects and, consequently, could be altered over the years.

To carry out the psychological assessment process, the participant was contacted by phone call and e-mail. Four meetings were held. The first one was to explain the process, establish rapport, and sign the informed consent form (ICF), authorizing the study and possible publication of the results and preserving the animate. The following meetings were dedicated to data collection through a semi-structured anamnesis interview, behavioral observation, genogram creation, and active listening. Each meeting lasted approximately one and a half hours.

For this study, a fictitious name was used to preserve the identity of the evaluated person as well as following all the ethical precepts established by the National Health Council/Brazil, Resolutions 466/2012 [

23] and 510/2016 [

24], and criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [

25].

4. Discussion and Results

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [

25], bipolar disorder has been reclassified and is now presented in its own specific chapter, separate from depressive disorders. It is recognized as a transitional disorder, sharing symptomatology, family history, and genetic factors with both depressive disorders and the schizophrenia spectrum. Bipolar disorder is characterized by mood episodes alternating between depressive states, characterized by profound sadness, and manic states, which involve extreme euphoria, or hypomania (a milder form of mania). The disorder can be further classified into different sub-types, including bipolar disorder type I and type II, cyclothymic disorder, bipolar disorder due to another medical condition, and substance-induced bipolar disorder, among others.

The differential diagnosis is based on the predominant mood state and the time interval between mood swings throughout an individual’s lifespan. For example, bipolar disorder type II requires a clinical course of recurrent mood episodes, consisting of one or more major depressive episodes and at least one hypomanic episode during the individual’s lifetime, with significant impairment in occupational and social functioning. The symptomatology for bipolar disorder type II with a recent episode of depression includes a persistent depressed mood, diminished interest or pleasure in almost all activities, insomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, a diminished ability to think or concentrate, and recurrent thoughts of death and suicidal ideation.

Personality disorders, on the other hand, are enduring patterns of inflexible traits and maladaptive symptoms that result in subjective distress and significant impairment in social and/or occupational functioning [

25].

The research by Vega Romero (2017) [

26] in the context of intimate partner violence suggests that women who are victims of such violence often exhibit dependent personality characteristics followed by mixed or obsessive–compulsive traits. While physical violence is the most reported form of abuse followed by emotional violence, they are not the only ones. Intimate partner violence encompasses any form of physical, psychological, or sexual aggression that infringes upon the couple’s freedom and results in detrimental effect effects on one's personal, physical, or mental well-being. Such violence against women is influenced by cultural factors; sociodemographic conditions; levels of social tolerance; and the psychopathological profiles of both the perpetrator and the victim, who frequently share the common traits of dependency, compulsivity, and low autonomy. Among women who experience violence and display dependent personality characteristics, 24.2% also exhibit other personality traits.

It is not worthy that certain personality disorders may have a spectrum relationship with other mental disorders or with other personality disorders as seen in the case of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and dependent personality disorder (DPD) [

25].

Furthermore, it is necessary to distinguish between personality disorders and a simple personality trait that does not meet the diagnostic criteria for a disorder. Personality traits are persistent patterns of perception relating to the environment and oneself observed in various social and personal contexts. They are only diagnosed as personality disorders when they are inflexible and enduring and when they significantly impair functioning and cause distress [

25].

Therefore, it is important to distinguish between BPD and DPD. Both disorders share a fear of abandonment but present notable differences in their reactions. In BPD, individuals typically react to abandonment with feelings of emotional emptiness and anger and demanding behaviors. Their relationships tend to be unstable and intense. On the other hand, individuals with DPD react to abandonment with a sense of calmness and submission, seeking replacement relationships urgently, as they strive for attention and care. Individuals with dependent personality disorder are often characterized by pessimism and insecurity. They tend to underestimate their abilities, perceiving criticism and disapproval as evidence of their worthlessness. They can go to extreme lengths to gain care and support from others. Their need to maintain an important connection comes up against imbalanced or distorted relationships. These individuals may make extraordinary sacrifices or tolerate verbal, physical, or sexual abuse under certain circumstances [

25].

The presence of separation anxiety disorder in childhood or adolescence may predispose a person to the development of dependent personality disorder. In borderline personality disorder, there is a generalized pattern of instability in one's interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affections. In addition to impulsiveness, it is characterized by desperate efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Relationships shift from idealization to devaluation. There is an instability of one's self-image or self-perception. There is also a recurrence of suicidal or self-mutilating behavior and affective instability due to accentuated mood reactivity associated with chronic feelings of emptiness. Finally, it is important not to diagnose personality disorders when features of bipolar disorder are observed, and there is no adequate follow-up or treatment [

25].

Thus, the results obtained in the process of the psychological evaluation of Maria allow us to affirm that the evaluated person presents a good intellectual performance and remains oriented but that she presents memory alterations. There is a deficit in her coping skills and adaptive responses in the face of experienced events with mood swings and the prevalence of a depressive state, characteristic of a bipolar disorder (296.89 DSM-V), expressed as depressed mood, decreased interest in life and pleasurable activities, fatigue, insomnia, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, suicidal ideation, and great anguish, allied to hypomania, expressed as excessive concern for her health and in the different areas of her professional activity (nursing, legal, and artistic). Added to this, she has a history of abusive relationships, which show physical, psychological, and sexual violence. Such behaviors suggest a dependent personality trait in addition to the evidence of borderline personality traits, highlighted by the instability of her self-image and self-perception, interpersonal relationships that change between idealization and devaluation, self-mutilation behaviors and suicidal ideation, and chronic feelings of emptiness. To this end, according to the clinical guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), a psychiatric follow-up is recommended so that the appropriate medication is used, aiming at mood stabilization, and psychotherapy is recommended, with the purpose of strengthening the healthy aspects of her psychic dynamics and developing emotional regulation and coping strategies to break the cycles of violence in order to minimize her anguish and recover her self-esteem in addition to strengthening her biopsychosocial aspects. In addition to emphasizing the dynamic nature of the psychological assessment, its results may change as a result of future circumstances.

5. Conclusions

The present study examined the effects of traumatic psychosocial environments on a 60-year-old woman who was a victim of abuse and child sexual abuse through active listening, aiming at a holistic view of her life history and biopsychosocial aspects. We concluded that an unstructured environment compromises the development of relational and coping skills, negatively influencing the mental health and quality of life of a victimized subject, especially when the subject does not have access to a protection network or public policies, particularly in underdeveloped countries such as Brazil.

A lack of support and adequate health treatment worsens psychic illness, culminating in symptoms and complex disorders, such as anxiety, depression, chemical dependency, self-mutilation, suicidal ideation, personality disorders, and bipolarity, among others.Early intervention and support for individuals with bipolar disorder and their families is crucial in mitigating the long-term effects of childhood trauma and promoting better mental health outcomes. It is important to invest in forms of free multi-disciplinary treatment, considering that there is an incidence of economic vulnerability in bipolar individuals. In addition, there is a need to give voice to their life stories through psychological assessments, providing opportunities for the resignification of their experiences and referrals that consider their biopsychosocial aspects without limiting them to quantitative data. It is important to recognize the limitations of this study both in terms of sample size and available information, which may be addressed in future research. Given the global prevalence of this issue along with the relatively sparse academic literature on the subject, further study is needed to expand our understanding.