Abstract

Men often perceive greater sexual willingness underlying women’s behaviors than women themselves intend. This discrepancy can contribute to sexual miscommunication and, sometimes, acts of sexual assault. The current study tested whether actor–observer asymmetry is present in women’s ratings of sexual intent to offer an additional explanation for past findings. We hypothesized that women rating their own behaviors would report less sexual intent compared to women rating another woman’s behaviors. We also hypothesized that these ratings would be influenced by the physical attractiveness of a male target through self-reported sexual arousal as a mediation pathway. Results from a community sample of 164 women (Mage = 42 years) generally supported these hypotheses. Sexual arousal was positively associated with ratings among all participants, but the mediation pathway was significant only for women rating another woman’s behavior. The findings suggested that actor–observer asymmetry is present in ratings of sexual intent. This effect might account for some of the sexual overperception phenomena and explain why third-party observers of women’s sexual behavior (e.g., potential partners, Title IX investigators, jurors) sometimes misinterpret sexual willingness.

1. Introduction

Prevalence estimates indicate that between 1.8% and 34% of female university students have experienced unwanted sexual contact [1]. Yet, most female university students (60.4%) who report experiencing unwanted sexual contact do not label the assault as such, instead characterizing situations that meet the legal definition of sexual assault as miscommunications [2,3,4]. People might attribute unwanted sexual contact to miscommunication due to the often indirect and nonverbal manner in which parties express and interpret sexual willingness and unwillingness [5,6]. Compared to women, men tend to systematically overperceive sexual intent on behalf of potential sexual partners [7], an error in social judgment that can contribute to sexual assault.

One explanation for this discrepancy in perceptions of sexual intent is the actor–observer asymmetry effect, whereby explanations for a given nonverbal behavior vary based on whether the person making the attribution is the performer of the behavior (i.e., the actor) or an observer of the behavior [8]. If actor–observer asymmetry exacerbates the gender difference in sexual overperception, women prompted to interpret the nonverbal behavior of another woman should report greater sexual intent compared to women reporting their own nonverbal behavior. Variables such as the physical attractiveness of the male target of the nonverbal behavior [9,10], as well as the participant’s sexual arousal [11,12,13], might also increase ratings of sexual intent underlying nonverbal behavior. The current study compared ratings of sexual intent between women rating their own behavior and women rating another woman’s behavior as a function of target attractiveness and mediated by the women’s present-state self-reported sexual arousal, to identify contributors to miscommunications of sexual intent which might lead to sexual assault. Hypotheses derived from the actor–observer asymmetry effect may provide an additional explanation for differences in sexual perception.

1.1. Actor–Observer Asymmetry

Actor–observer asymmetry occurs when actors in a given social interaction tend to make situational attributions to explain their own behavior, whereas observers tend to make dispositional attributions to explain the actor’s behavior [8,14]. In one study reporting the causes of their own risky driving behavior (e.g., speeding, swerving between lanes), actors most often attributed recklessness to being late and hurrying to their destination (i.e., a situational attribution). Reporting on the causes of a friend’s behavior, in contrast, observers most often attributed recklessness to a propensity to show off (i.e., a dispositional attribution) [15]. Similar patterns emerge when actors and observers attempt to explain relationship infidelity [16], assess information technology threats [17], and make legal decisions [18]. Actor–observer asymmetry occurs in part because actors have a more thorough knowledge of their inner experiences (e.g., affectivity, motivations) compared to observers, the latter of whom can only assume the causes of the actor’s behavior. Interventions that instruct actors and observers to take the perspective of the other party can reduce asymmetry [16,19].

The actor–observer asymmetry effect could partially account for discrepancies between women’s and men’s interpretations of ambiguous nonverbal behaviors that might, or might not, indicate sexual willingness (e.g., smiling, pulling a person closer; tensing up, looking away) [5,6]. Differences in perspective, in addition to gender differences in sexual perception [20,21], might help to explain why men interpret sexual willingness from ambiguous behaviors to a greater degree than women report themselves [22]. Indeed, women and men rated 15 behaviors, from Haselton and Buss (2000), indicating a greater sexual intent when performed by someone else versus themselves [23]. The current study examined this actor–observer difference among a sample of women using a 25-item instrument that manipulated the participants’ perspective and measured perceptions of sexual intent [12,13,24].

1.2. Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Sexual Decision Making

The physical attractiveness of a potential sexual partner might influence women’s ratings of sexual intent consistent with the “what is beautiful is good” hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that people harbor more favorable perceptions of physically attractive versus unattractive others including perceptions of attractive people as having better personalities, fulfilling more satisfying occupational roles, and making better marriage partners [25]. Such favorable perceptions can enhance an attractive person’s sexual prospects [10]. Women and men, in one study, expressed a greater willingness to have casual sex with a partner more attractive than themselves (vs. equally attractive) [26], perhaps because they perceived more physically attractive partners to pass on more desirable genetic traits to offspring and to be less likely to carry a sexually transmitted infection (STI) [27,28].

Refuting the latter explanation, other research indicated that participants perceived attractive others to be at greater risk for STIs due to sexual opportunities afforded by good looks [29,30]. Yet, the “what is beautiful is good” effect is so influential on sexual decision making that, despite believing more attractive men to harbor greater STI risk, women reported greater willingness to engage in both protected and unprotected sex with attractive (vs. unattractive) men [9]. Because women perceive more attractive men to make more viable sexual partners, we expected the attractiveness of the male target of sexual communication to affect women’s ratings of sexual intent. Further, we expected this relationship to be mediated by women’s sexual arousal.

1.3. Effects of Sexual Arousal on Sexual Decision Making

Conceptualized as a drive state, sexual arousal focuses attention on the gratification of sexual desires and temporarily suppresses inhibitions [31,32]. Transient cognitive changes associated with sexual arousal influence sexual decision making. For example, men report a greater willingness to engage in unethical or unsafe sexual behaviors while experiencing higher (vs. lower) sexual arousal [33] and greater endorsement of sexually aggressive [32] or coercive [11] behavior.

Other findings suggest similar cognitive orientations in response to sexual arousal among women. In one study [34], women’s sexual arousal was positively associated with the endorsement of the belief that women say “no” to sex when they really mean “yes” (i.e., token resistance [35]) and with preferences for men who act with sexual assertiveness (e.g., undressing a woman without asking first). Sexual arousal also influences interpretations of sexual communication, with sexually aroused men—especially single men not in current romantic relationships—interpreting greater sexual willingness from women’s ambiguous behaviors [12,13]. The current study replicated and extended this effect among a community sample of women and tested sexual arousal as a mediator of the relationship between target attractiveness and ratings of sexual intent. We predicted that women would report greater sexual arousal when imagining a sexual scenario featuring a male target of high versus low physical attractiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

The study used a 2 (target physical attractiveness: high vs. low) × 2 (performer of behavior: self vs. another woman) between-participants experimental design. Participants received a random assignment to view a photo of a man of high (n = 81) or low (n = 83) physical attractiveness while they responded to questions about the meaning of their own (n = 77) or another woman’s (n = 87) behavior when the man photographed, arbitrarily named Ben, was the target of that behavior. We tested the model that target attractiveness would influence ratings of women’s own or another woman’s sexual intent mediated by the participants’ self-reported sexual arousal. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at a university in the southern U.S.

2.1. Participants

Participants were Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers who completed the study in exchange for USD 0.20. Women located in the U.S. who had completed at least 500 MTurk tasks with an approval rate of 90% or higher were eligible to participate in the study. These a priori inclusion criteria helped to protect the quality of participants’ responses consistent with scholarship examining MTurk recruitment methodologies, [36,37,38] which facilitate cost-effective data collection and similar data reliability compared to other online methods [39].

An a priori power analysis conducted in G*Power [37,40] assuming a small-to-medium effect of f2 = 0.10 indicated 100 participants would be necessary to achieve a statistical power of 1 − β = 0.80 for simple mediation analyses. The remainder of the present analyses required fewer participants, assuming the same effect size and power level. The final sample contained 164 heterosexual female participants with a mean age of 42.46 years (SD = 12.89). Most participants identified as White (79.9%), followed by Black (8.5%), Asian (4.9%), Native American (3.7%), Latinx (1.8%), and Other (1.2%). See Table 1 for demographic characteristics separated by experimental conditions.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics separated by experimental conditions.

We oversampled to account for sample size reduction during data cleaning based on the a priori removal criteria. The full sample, before applying the exclusion criteria, consisted of 207 participants, all of whom received monetary compensation. We excluded 43 participants from the data analysis due to either (1) identifying their sexual orientation as homosexual or (2) speeding through the survey. First, it was imperative to the study’s hypotheses that participants self-identified as heterosexual because their task was to interpret sexual intent in an opposite-sex interaction. Thirty-six participants failed to respond to the measure of sexual orientation [41] or self-reported their sexuality as “more than incidentally homosexual” and were subsequently removed from the dataset. Second, based on a survey pretest consisting of 35 student participants (this pretest occurred in a closed-door lab setting. Although students were not under direct observation, they had worked with an experimenter up to this point and knew they could not click through the study rapidly and leave without being noticed. Only one student finished in under 180 s. The remainder finished in no less than 247 s), we established a cut-off of 180 s or more to complete the survey with adequate attention. In total, 7 participants who spent less than 180 s completing the survey were removed from the dataset.

2.2. Materials

Study materials are available via the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/YA2VW). Following the random assignment to one of the four experimental conditions, participants responded to three dependent measures. These measures included a rating of target physical attractiveness, ratings of women’s sexual intent, and participants’ self-reported sexual arousal.

2.2.1. Target Physical Attractiveness

Participants viewed a headshot of a man of high (M = 4.59/5.00) or low (M = 2.14/5.00) physical attractiveness based on rating data from the Chicago Face Database [42] The photos were similar in other dimensions including age (Mhigh attractiveness = 28.59; Mlow attractiveness = 24.97) and race (White). To assess the effectiveness of the physical attractiveness manipulation, participants rated the man’s attractiveness on a scale from 1 (not at all physically attractive) to 7 (very physically attractive).

2.2.2. Ratings of Sexual Intent

Ratings of sexual intent served as the study’s primary dependent variable. We measured this construct using a scale with high internal consistency adapted from prior research (α = 0.92–0.95) [12,13,24]. The scale consists of 25 items each rated on a continuous 7-point scale (see Table 2 for items and mean ratings separated by condition). We adapted the instructions for the measure, as well as the scale endpoints, to manipulate whether participants rated their own sexual intent or that of another woman. For participants randomly assigned to rate their own sexual intent, instructions read: “Imagine that you engage in each of these behaviors with Ben (the man depicted in the photo). Then, indicate how likely it is that this behavior means you want to have sex with Ben.” For participants randomly assigned to rate another woman’s sexual intent, instructions read: “Imagine that a woman engaged in each of these behaviors with Ben. Then, indicate how likely it is that this behavior means she wants to have sex with Ben.” The 25 behaviors included items such as going to lunch with the man, going to the man’s residence during a date to be alone, and touching the man’s bare genitals. Participants rated each behavior from 1 (this behavior does NOT AT ALL mean I want [she wants] to have sex) to 7 (this behavior DEFINITELY means I want [she wants] to have sex). Some items contained an error in the pronoun (“I” vs. “she”) listed in the response scale. To ensure this error did not affect the present results, we re-ran all statistical analyses, omitting the specific items that contained this error, and compared the results to those reported in the manuscript. None of the results differed significantly. Additionally, the complete dependent measure reported in the manuscript was highly reliable across conditions (αs > 0.92), suggesting that the error did not affect the participants’ responses to the dependent measure.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations for the measure of ratings of sexual intent 1. Instructions: Imagine that you [a woman] engaged in each of these behaviors with Ben. Then, indicate how likely it is that this behavior means you want [she wants] to have sex with Ben.

2.2.3. Self-Reported Sexual Arousal

Participants self-reported their present-state sexual arousal on a scale from 1 (not at all sexually aroused) to 7 (extremely sexually aroused). Single-item measures of sexual arousal reliably captured differences in self-reported sexual arousal in prior research [11,12,13].

2.3. Procedure

Participants who agreed to proceed with the study provided demographic information including their sex, sexual orientation, age, and race/ethnicity. Then, participants received random assignment via Qualtrics randomization to one of four experimental conditions. Based on this randomization, participants viewed a photo of either an attractive or unattractive male target and responded to the primary dependent measure from their own perspective or from the perspective of another woman. The photo of the attractive or unattractive male target remained visible to participants through the duration of the primary dependent measure to facilitate a consistent effect of the manipulation. Next, participants self-reported their present-state sexual arousal, which we hypothesized would mediate the effect of target attractiveness on sexual intent ratings. We expected that participants who imagined a series of sexual acts would become, at least somewhat, sexually aroused and that the attractive (vs. unattractive) male target would elicit greater sexual arousal. Finally, participants read a debriefing statement and received a unique code to redeem their compensation. The mean time to complete the study was approximately six minutes.

2.4. Analytical Strategy

All continuous variable distributions were normal with skewness and kurtosis within the range of ±2, requiring no transformation [43]. Levene’s tests indicated that the variances of continuous variables were not significantly different between the experimental groups (ps > 0.25). Data met the statistical assumptions to test the present hypotheses.

Independent samples t-tests examined (1) the effectiveness of the manipulation of target attractiveness, and (2) the effect of target attractiveness on ratings of sexual intent. Further, a two-way ANOVA examined the effects of target attractiveness conditions and performer of behavior conditions on self-reported sexual arousal. Finally, we conducted mediation analyses using updated Baron and Kenny procedures [44,45] to test the hypothesis that target attractiveness would affect ratings of sexual intent through sexual arousal as an indirect pathway. We assessed each dependent variable with a formal mediation model using Lavaan [46] in RStudio [47].

3. Results

3.1. Target Attractiveness Manipulation Check

A t-test indicated that the attractiveness manipulation was effective (t(162) = 7.91, p < 0.001, d = 1.23). The attractive male target received significantly higher attractiveness ratings (M = 5.00; SD = 1.38) than the unattractive male target (M = 3.16; SD = 1.59).

3.2. Effects of Target Attractiveness and Performer of Behavior

First, we examined the effects of target attractiveness (high vs. low) and performer of behavior (self vs. another woman) on self-reported sexual arousal using a two-way ANOVA. A main effect of target attractiveness emerged (F(1158) = 4.05, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.02) such that women assigned to the attractive target condition reported significantly higher sexual arousal (M = 3.18; SD = 2.05) compared to women assigned to the unattractive target condition (M = 2.54; SD = 1.95). There was no main effect of the performer of behavior condition and no interaction.

We created the mean composite measures of ratings of sexual intent scale for the self and for another woman, each of which demonstrated high internal consistency (αs > 0.92). A t-test examining the effect of target attractiveness on women’s own sexual intent revealed no significant difference between attractiveness conditions. However, a t-test examining the effect of target attractiveness on another woman’s sexual intent revealed that participants provided higher ratings of sexual intent when the target was attractive (M = 4.25; SD = 1.38) versus unattractive (M = 3.61; SD = 1.22; t(162) = 2.27, p = 0.03, d = 0.51). Women who viewed the attractive photo interpreted more sexual intent in another woman’s behavior (M = 4.25) than the participants who viewed the unattractive photo (M = 3.61). Perceptions of sexual intent also did not significantly differ as a function of whether women were rating their own behavior versus another woman’s behavior across attractiveness conditions.

Next, we used two simple regression analyses to test the predictive effect of self-reported sexual arousal on ratings of sexual intent. Self-reported sexual arousal was positively predictive of sexual intent ratings among women interpreting their own behavior (b = 0.39, t(73) = 9.43, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.39, f2 = 0.61) as well as among women interpreting another woman’s behavior (b = 0.46, t(89) = 9.43, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.51, f2 = 0.68).

3.3. Mediation Analyses

Next, we tested whether sexual arousal mediated the relationship between manipulated target attractiveness (low vs. high) and ratings of sexual intent. Because target attractiveness significantly affected self-reported sexual arousal, and because self-reported sexual arousal significantly predicted both dependent variables, it was possible to examine the indirect effects of target attractiveness on both outcome variables through self-reported sexual arousal [45,48,49]. Each of the mediation models contained two sets of regression equations: The first equation used ratings of sexual intent as the dependent variable, and target attractiveness and self-reported sexual arousal as predictors. The second regression equation used target attractiveness to predict self-reported sexual arousal. Each model was bootstrapped to 10,000 iterations.

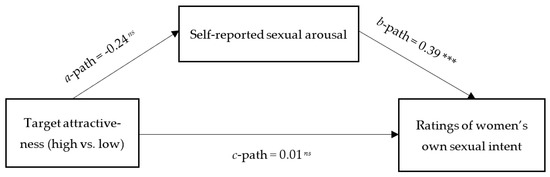

The first mediation model tested the predictive effects of target attractiveness and self-reported sexual arousal on ratings of women’s own sexual intent (see Figure 1). The overall model was significant (F(2,72) = 22.67, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.39), indicating that these two predictor variables explained 39% of the variance in ratings of women’s own sexual intent. The first simple regression revealed a nonsignificant direct effect of target attractiveness on ratings of sexual intent (c-path). Because a significant direct effect is not necessary to test for mediation [50], we continued to examine the pathway through self-reported sexual arousal. However, target attractiveness did not predict self-reported sexual arousal (a-path). Self-reported sexual arousal positively predicted ratings of sexual intent (b-path; b = 0.39, z = 6.45, p < 0.001, CI [0.28, 0.52]), but nonsignificant a- and c-paths indicated a lack of mediation.

Figure 1.

Mediation analysis depicting the effect of target attractiveness on ratings of women’s own sexual intent through self-reported sexual arousal 1. 1 Note. *** = p < 0.001, ns = nonsignificant. Path coefficients represent unstandardized beta scores.

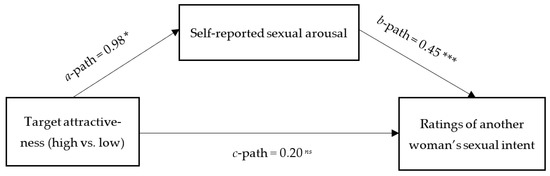

The second mediation model tested the predictive effects of target attractiveness and self-reported sexual arousal on ratings of another woman’s sexual intent (see Figure 2). The overall model was significant (F(2,83) = 44.94, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.52), indicating that these two predictor variables explained 52% of the variance in ratings of another woman’s sexual intent. The first simple regression again revealed a nonsignificant direct effect of target attractiveness on ratings of sexual intent (c-path). Target attractiveness positively predicted self-reported sexual arousal (a-path; b = 0.98, z = 2.25, p = 0.03, CI [0.09, 1.85]), and self-reported sexual arousal positively predicted ratings of sexual intent (b-path; b = 0.45, z = 9.72, p < 0.001, CI [0.35, 0.54]). This pattern resulted in a significant indirect effect of target attractiveness on ratings of another woman’s sexual intent through self-reported sexual arousal (b = 0.44, z = 2.13, p = 0.03, CI [0.04, 0.87]).

Figure 2.

Mediation analysis depicting the effect of target attractiveness on ratings of another woman’s sexual intent through self-reported sexual arousal 1. 1 Note. *** = p < 0.001, * = p < 0.05, ns = nonsignificant. Path coefficients represent unstandardized beta scores.

4. Discussion

The current study examined the extent to which actor–observer asymmetry could explain discrepant accounts of sexual willingness. We hypothesized that a male target’s physical attractiveness would affect women’s self-reported sexual arousal, which in turn would affect ratings of their own or another woman’s sexual willingness. Findings indicated that target attractiveness did not directly predict ratings of sexual intent. However, for women rating another woman’s sexual willingness, the indirect pathway through self-reported sexual arousal was significant. For all women, self-reported sexual arousal positively predicted ratings of sexual intent. These results provided evidence of actor–observer asymmetry in women’s ratings of sexual intent and illuminated relationships between target attractiveness and sexual arousal.

4.1. Actor–Observer Asymmetry in Sexual Decision Making

Results indicated that target physical attractiveness indirectly influenced women’s ratings of others’ sexual intent, but not their own. Moreover, self-reported sexual arousal provided a significant explanatory pathway only for ratings of another woman’s sexual intent. An integration of sexual strategies theory [51] and perspectives on motivated reasoning [52] offers an explanation for the observed asymmetry between actor and observer perceptions. Due to their greater investment in offspring compared to men [53], women consider diverse factors when deciding whether to engage in sex [51]. However, women might rely on more superficial information when deciding whether someone else should engage in sex, as the decision maker herself is not responsible for outcomes associated with another woman’s sexual behavior. In such a situation, as was the case in the current study, observers might be more likely to rely on the target’s physical attractiveness and their own sexual arousal. Actors, on the other hand, might utilize a more stringent set of criteria in sexual decision making. The present findings suggested that actors versus observers might engage in differential decision making processes when rating women’s sexual intent. Among actors, a male target’s physical attractiveness did not affect ratings of sexual intent through sexual arousal. However, among observers, a male target’s physical attractiveness indirectly predicted ratings of sexual intent through sexual arousal. The finding that sexual arousal serves as a mediating variable among observers but not among actors suggests differences in sexual thinking and decision making depending on a person’s perspective in ambiguous sexual scenarios.

The current findings among a sample of women help to explain discrepancies between women’s and men’s perceptions of sexual intent in prior research [7,20,24]. Men might systematically overperceive sexual intent because they are often situated as observers of women’s sexual behavior, whereas women are often situated as actors or “gatekeepers” deciding whether a given man meets their criteria for a sexual partner [6]. Men, in prior studies, seemed to infer that their sexual arousal was predictive of a potential partner’s sexual arousal; thus, they interpreted their partner’s behavior in a motivated manner [52] consistent with engaging in sex [12,13]. The current study replicated this effect among women. Present findings suggest that gender might be confounded with actor–observer perspective as an explanation for discrepant sexual perceptions between women and men. That is, some variance in interpretations of sexual willingness traditionally attributed to gender differences is likely attributable to a person’s perspective on the sexual interaction.

The effects of actor–observer asymmetry in sexual decision making extend beyond discrete instances of sexual communication (and miscommunication). Misunderstandings of the sexual intent or non-intent underlying a potential partner’s nonverbal behavior can contribute to sexual assault on university campuses and beyond. These instances of sexual assault are difficult to quantify or try in legal proceedings because they often lack objectively verifiable evidence and can be plausibly attributed to an honest misunderstanding on the part of the alleged aggressor [54]. Lacking validation by authorities or Title IX investigators, victims of these instances of sexual assault can internalize blame for failing to convey their lack of sexual willingness more clearly [4]. This cascade of effects resulting from actor–observer asymmetry might explain why victims are often hesitant to report sexual assault to Title IX offices [55]. Title IX coordinators, investigators, administrative panels, and even judges and jurors are situated as post hoc observers of the sexual interaction—not actors—and thus their attributions of the behaviors that led to the alleged sexual assault might be influenced by actor-observer asymmetry. Observers might attribute women’s involvement in the sexual situation to the man’s attractiveness or to her sexual arousal (i.e., dispositional factors), whereas actors might identify aggression or coercion (i.e., situational factors). Novel approaches to addressing sexual assault allegations, such as restorative justice models which allow victims to share their personal accounts with investigators and alleged perpetrators [56], might serve to reduce the gap between actor and observer. It is perhaps for this reason that victims sometimes prefer restorative justice approaches over conventional approaches to criminal justice [57].

4.2. Influences of Target Attractiveness

Observers’ decision making criteria might be simplified compared to that of the actors. Women in the current study who rated their own sexual intent did not report greater sexual intent toward an attractive versus unattractive male target. However, women who rated another women’s sexual intent provided higher ratings when the target was attractive. Perhaps “what is beautiful is good” for someone else, but not always for oneself [25]. This finding lends enhanced nuance to the interpretation of past research examining the effects of men’s attractiveness on women’s sexual willingness and identifies future directions.

One past study found that women reported greater willingness to engage in sex with an attractive versus unattractive man, despite believing the attractive man was more likely to carry an STI [9,29]. Given the current findings, as well as evidence from evolutionary psychology [51,53], it is striking that prior research revealed this direct effect of physical attractiveness. In general, women often demonstrate more stringent criteria for selecting sexual partners compared to men or compared to the participants in Lennon and Kenny’s (2013) research [9,58]. Perhaps some of the difference between the current findings and those of Lennon and Kenny (2013) is explained by divergent samples: Whereas Lennon and Kenny (2013) recruited university student participants who are more likely to engage in casual sexual activity with short-term mating goals (e.g., gratification [59,60]), older samples from the general population hold more conservative attitudes toward casual sex [61]. Research should continue to clarify the potential influences of demographic differences on ratings of sexual willingness. Given that relationship status influenced men’s ratings of sexual intent in prior research [12,13], future studies should examine similar patterns in women’s ratings.

Differential sexual strategies employed by research participants in various samples could offer another explanation for the observed inconsistencies with past research. Younger samples often report willingness to engage in casual sex as a means of facilitating a romantic relationship [62] or coping with anxious attachment [63,64]. Because older people are more likely to be in married relationships [65], and because attachment anxiety decreases with age [66], our older sample might not endorse communication of sexual intent as a strategy to begin or maintain a relationship. However, participants from this sample might perceive that other women would likely employ such a strategy to obtain an attractive partner, hence the difference in actor–observer ratings as well as in findings between the current study and past work.

Actor–observer differences have implications for how third-party arbiters might judge allegations of sexual misconduct. The present findings suggest that when a potential male sexual partner is physically attractive, third-party observers might perceive greater sexual intent underlying a woman’s behavior compared to women reporting on their own behavior. This pattern of results is consistent with prior work indicating that raters were less likely to classify behavior as sexual harassment when the person performing the behavior was of high (vs. low) physical attractiveness, both in a workplace context [67,68] and in higher education [69]. Judges, jurors, and university Title IX officers might similarly interpret greater sexual intent underlying women’s nonverbal behavior than women meant to convey, especially when the accused party is physically attractive [70]. Third-party arbiters should be aware of potential interactions between actor–observer differences and physical attractiveness bias when evaluating allegations of sexual harassment or misconduct. Educational interventions designed to increase awareness of and concern about bias have demonstrated effectiveness in other domains [71].

4.3. Influences of Participant Sexual Arousal

Self-reported sexual arousal predicted ratings of sexual intent regardless of whether women rated their own or another woman’s behavior. This finding replicates the link between sexual arousal and sexual intent documented in past research using a variety of samples, research designs, and dependent measures [11,12,13,33,72]. Sexual arousal is a drive state that focuses attention on obtaining sex and suppressing goal-inconsistent signals, sometimes leading to sexual aggression [32] or coercion [11]. Past research provided evidence that sexual arousal enhances the perception of sexual willingness [11,12,13]. Present findings suggest that sexual arousal is positively related to the self-reported sexual intent underlying women’s behaviors. Together, these findings further elucidate a model of sexual arousal that momentarily orients social cognition toward the fulfillment of sex-related goals despite possible risks (e.g., unethical behavior [33], sexual aggression [32], STIs [9,29]). These effects appear to be strongest among men and among women rating other women’s (vs. their own) behavior.

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

The current study is not without limitations that future research should address. First, the present study utilized a between-participants design. This design facilitated experimental control while avoiding the influence of order effects. Although effective at testing novel hypotheses regarding actor–observer asymmetry in the context of sexual communication, this design does not allow for within-participant comparisons between actor and observer perspectives. Future research should replicate and extend the current findings using a variety of experimental and correlational research designs. A repeated measures design would allow for within-participant comparisons as both actor and observer.

Second, the present study recruited women from a community sample of MTurk workers. Samples from MTurk offer greater age diversity and more varied life experiences [73], which can produce more generalizable findings compared to university student samples. However, given the prevalence of casual sex [60] and sexual assault accusations [1] among university students, future research examining the predictors of sexual miscommunication should also recruit university students to best serve this population. Comparative analyses between these populations can discern population-specific effects from broadly applicable findings. In addition, the greater age diversity of our sample compared to a typical university student sample entailed a trade-off such that participants evaluated the physical attractiveness of photographed male targets who were younger than the mean age of our research participants. Future research should replicate these effects among a university student population or among a community sample using photographs of age-matched targets. Such replications could demonstrate the extent to which the present findings generalize to diverse populations. Further, despite evidence that data collected via MTurk are similarly reliable to other online sampling strategies [39], limitations persist regarding the representativeness of MTurk samples. MTurk samples tend to skew young and White compared to the general population [74]. Given these sample limitations, the present hypotheses should be examined with more representative samples obtained through varied recruitment methodologies. Continued investigations can support or refute the present preliminary results.

Third, it was beyond the scope of the present study to examine how individual difference variables (e.g., age, sexual attitudes, religiosity) might influence ratings of sexual intent. Future research should investigate these relationships. Sociodemographic variables did not differ significantly between experimental conditions in the current study due to its experimental design which randomly assigned participants to conditions (see Table 1). This homogeneity of sociodemographic characteristics suggested that the experimental manipulation of actor–observer perspective, rather than extraneous sociodemographic factors, produced the observed effects on the present dependent measures. However, future research should examine whether individual differences can account in part for women’s ratings of sexual intent. For instance, participants with more sex-positive attitudes might perceive hypothetical dating scenarios to be less risky compared to participants with less sex-positive attitudes. This hypothesis is consistent with the research, indicating that exposure to sexual media (e.g., television programs, video games, internet videos) is positively associated with permissive sexual attitudes and risky sexual behavior [75]. Other sociodemographic variables, such as religiosity [76] and education [77], may be negatively associated with permissive sexual attitudes and risky sexual behavior. Future research should continue to examine these individual difference variables to help explain perceptions of nonverbal behaviors which may or may not communicate sexual willingness.

Fourth, the present study measured, but did not manipulate, women’s sexual arousal. Recent research [34] indicates that sexual arousal temporarily increases women’s belief in token resistance [35] (i.e., the notion that women sometimes reject a sexual offer when they are privately willing) and their endorsement of men’s assertive sexual behavior. The current study provided evidence that self-reported sexual arousal also predicts women’s ratings of their own and others’ sexual intent. Future research should manipulate sexual arousal to examine the extent to which this experimental factor might amplify or minimize observed actor–observer asymmetry.

5. Conclusions

Many victims of sexual assault attribute their experiences to miscommunication [4]. The current research offered insights regarding the bases of sexual miscommunication by manipulating women’s perspectives (actor vs. observer) on a potentially sexual interaction with a man of high or low physical attractiveness and measuring their ratings of sexual intent underlying nonverbal behaviors. The findings suggested that women’s self-reported sexual arousal explained the relationship between target attractiveness and ratings of sexual intent, but only for women rating another women’s (vs. their own) behavior. Actor–observer differences might account for some of the discrepancies between women’s and men’s sexual perceptions [7] and provide a target for addressing sources of sexual miscommunication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N.L. and P.O.R.; methodology, T.N.L. and P.O.R.; formal analysis, P.O.R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.N.L.; writing—review and editing, T.N.L. and P.O.R.; visualization, T.N.L.; funding acquisition, P.O.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Oklahoma City University (protocol code PR101121, approved on 11 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available via the corresponding author. Materials are available via the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/YA2VW).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fedina, L.; Holmes, J.L.; Backes, B.L. Campus Sexual Assault: A Systematic Review of Prevalence Research from 2000 to 2015. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 10 USC 920: Art. 120. Rape and Sexual Assault Generally. Available online: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title10-section920&num=0&edition=prelim (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Dardis, C.M.; Kraft, K.M.; Gidycz, C.A. “Miscommunication” and Undergraduate Women’s Conceptualizations of Sexual Assault: A Qualitative Analysis. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.C.; Miller, K.E. Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Unacknowledged Rape. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016, 17, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, M. Sexual Miscommunication? Untangling Assumptions about Sexual Communication between Casual Sex Partners. Cult. Health Sex. 2010, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozkowski, K.N.; Peterson, Z.D. College Students and Sexual Consent: Unique Insights. J. Sex Res. 2013, 50, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselton, M.G. The Sexual Overperception Bias: Evidence of a Systematic Bias in Men from a Survey of Naturally Occurring Events. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.E.; Nisbett, R.E. The Actor and the Observer: Divergent Perceptions of the Causes of Behavior. In Attribution: Perceiving the Causes of Behavior; General Learning Press: Morristown, NJ, USA, 1972; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, C.A.; Kenny, D.A. The Role of Men’s Physical Attractiveness in Women’s Perceptions of Sexual Risk: Danger or Allure? J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, G.; Simmons, L.W.; Peters, M. Attractiveness and Sexual Behavior: Does Attractiveness Enhance Mating Success? Evol. Hum. Behav. 2005, 26, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, J.A.; Miller, H.A. The Role of Sexual Arousal and Overperception of Sexual Intent Within the Decision to Engage in Sexual Coercion. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 1967–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, T.N.; Rerick, P.O.; Davis, D. Relationships Between Sexual Arousal, Relationship Status, and Men’s Ratings of Women’s Sexual Willingness: Implications for Research and Practice. Violence Gend. 2022, 9, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerick, P.O.; Livingston, T.N.; Davis, D. Does the Horny Man Think Women Want Him Too? Effects of Male Sexual Arousal on Perceptions of Female Sexual Willingness. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 160, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, B.F. The Actor-Observer Asymmetry in Attribution: A (Surprising) Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 895–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harre, N.; Brandt, T.; Houkamau, C. An Examination of the Actor-Observer Effect in Young Drivers’ Attributions for Their Own and Their Friends’ Risky Driving. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 806–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulibert, D.; Thompson, A.E. Stepping into Their Shoes: Reducing the Actor-Observer Discrepancy in Judgments of Infidelity through the Experimental Manipulation of Perspective-Taking. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 159, 692–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuijten, A.; Keil, M.; Pijl, G.V.D.; Commandeur, H. IT Managers’ vs. IT Auditors’ Perceptions of Risks: An Actor–Observer Asymmetry Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelderman, L.A.; Lawrence, T.I.; Lyons, C.E.; DeVault, A. Actor–Observer Asymmetry in Perceptions of Parole Board Release Decisions. Psychiatry Psychol. Law 2021, 28, 623–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storms, M.D. Videotape and the Attribution Process: Reversing Actors’ and Observers’ Points of View. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1973, 27, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselton, M.G.; Buss, D.M. Error Management Theory: A New Perspective on Biases in Cross-Sex Mind Reading. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, K.P.; Parkhill, M.R.; George, W.H.; Hendershot, C.S. Gender Differences in Perceptions of Sexual Intent: A Qualitative Review and Integration. Psychol. Women Q. 2008, 32, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, D.R.; Murphy, S.C.; Von Hippel, W.; Trivers, R.; Haselton, M.G. A Preregistered Study of Competing Predictions Suggests That Men Do Overestimate Women’s Sexual Intent. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeler, I.; Raghubir, P. Decomposing the Cross-Sex Misprediction Bias of Dating Behaviors: Do Men Overestimate or Women Underreport Their Sexual Intentions? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 114, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, T.N.; Davis, D. Power Affects Perceptions of Sexual Willingness: Implications for Litigating Sexual Assault Allegations. Violence Gend. 2020, 7, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, K.; Berscheid, E.; Walster, E. What Is Beautiful Is Good. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 24, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surbey, M.K.; Conohan, C.D. Willingness to Engage in Casual Sex: The Role of Parental Qualities and Perceived Risk of Aggression. Hum. Nat. 2000, 11, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanton, H.; Gerrard, M. Effect of Sexual Motivation on Men’s Risk Perception for Sexually Transmitted Disease: There Must Be 50 Ways to Justify a Lover. Health Psychol. 1997, 16, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Hennessy, M.; Yzer, M.; Curtis, B. Romance and Risk: Romantic Attraction and Health Risks in the Process of Relationship Formation. Psychol. Health Med. 2004, 9, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, P.; Buunk, B.P.; Blanton, H. The Effect of Target’s Physical Attractiveness and Dominance on STD-Risk Perceptions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 1738–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, T.; Davis, A.L.; Fischhoff, B. Inferring Sexually Transmitted Infection Risk From Attractiveness in Online Dating Among Adolescents and Young Adults: Exploratory Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e14242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Loewenstein, G. Drive States. In Noba Textbook Series: Psychology; DEF publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein, G. Out of Control: Visceral Influences on Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 65, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, D.; Loewenstein, G. The Heat of the Moment: The Effect of Sexual Arousal on Sexual Decision Making. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2006, 19, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerick, P.O.; Livingston, T.N.; Davis, D. Let’s Just Do It: Sexual Arousal’s Effects on Attitudes Regarding Sexual Consent. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlenhard, C.L.; Hollabaugh, L.C. Do Women Sometimes Say No When They Mean Yes? The Prevalence and Correlates of Women’s Token Resistance to Sex. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, G.; Chandler, J.; Ipeirotis, P.G. Running Experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, G.; Chandler, J. Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a Participant Pool. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, E.; Vosgerau, J.; Acquisti, A. Reputation as a Sufficient Condition for Data Quality on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 2014, 46, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmester, M.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A New Source of Inexpensive, Yet High-Quality, Data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, A.C.; Pomery, W.B.; Martin, C.E. Kinsey Scale. 1948. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft17515-000 (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Ma, D.S.; Correll, J.; Wittenbrink, B. The Chicago Face Database: A Free Stimulus Set of Faces and Norming Data. Behav. Res. Methods 2015, 47, 1122–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Assessing Normal Distribution (2) Using Skewness and Kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. 2020. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Kenny, D.A.; Korchmaros, J.D.; Bolger, N. Lower Level Mediation in Multilevel Models. Psychol. Methods 2003, 8, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J. Current Directions in Mediation Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, H.P.; MacKinnon, D.P. Reasons for Testing Mediation in the Absence of an Intervention Effect: A Research Imperative in Prevention and Intervention Research. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2018, 79, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.M. Sexual Strategies Theory: Historical Origins and Current Status. J. Sex Res. 1998, 35, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunda, Z. The Case for Motivated Reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorklund, D.F.; Shackelford, T.K. Differences in Parental Investment Contribute to Important Differences Between Men and Women. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1999, 8, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, J.G.; Davis, D.; Leo, R.A. His Story; Her Story. In Wrongful Allegations of Sexual and Child Abuse; Burnett, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J. The Constraints of Fear and Neutrality in Title IX Administrators’ Responses to Sexual Violence. J. High. Educ. 2021, 92, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, M.P. The RESTORE Program of Restorative Justice for Sex Crimes: Vision, Process, and Outcomes. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 1623–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, C.; Westmarland, N.; Godden, N. ‘I Just Wanted Him to Hear Me’: Sexual Violence and the Possibilities of Restorative Justice. J. Law Soc. 2012, 39, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.M.; Schmitt, D.P. Sexual Strategies Theory. In Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science; Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, S.B. Beyond Risk: Examining College Students’ Sexual Decision Making. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2010, 5, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, J.M.; Wasserman, T.H. Sexual Hookups Among College Students: Sex Differences in Emotional Reactions. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2011, 40, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Sherman, R.A.; Wells, B.E. Changes in American Adults’ Sexual Behavior and Attitudes, 1972–2012. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 2273–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; Gordon, B. Young New Zealand Women’s Sexual Decision Making in Casual Sex Situations: A Qualitative Study. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2015, 24, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Shaver, P.R.; Vernon, M.L. Attachment Style and Subjective Motivations for Sex. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Shaver, P.R.; Widaman, K.F.; Vernon, M.L.; Follette, W.C.; Beitz, K. “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction”: Insecure Attachment, Inhibited Sexual Communication, and Sexual Dissatisfaction. Pers. Relatsh. 2006, 13, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, P.; McGill, B.; Chandra, A. Who Marries and When? Age at First Marriage in the United States: 2002; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, L.; Luyten, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Persoons, P.; Van De Ven, L.; Vandenbulcke, M. Attachment in Old Age: Theoretical Assumptions, Empirical Findings and Implications for Clinical Practice. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savery, M.E. Sexual Harassment Perception as Influenced by a Harasser’s Physical Attractiveness and Job Level. Mod. Psychol. Stud. 1997, 5, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, J.H.; Johnson, C.A.; Lopez, R.A. Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: Exploring the Effects of Attractiveness on Perception of Harassment. Sex Roles 2001, 45, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocca, M.A.; Kromrey, J.D. The Perception of Sexual Harassment in Higher Education: Impact of Gender and Attractiveness. Sex Roles 1999, 40, 921–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellow, W.A.; Wuensch, K.L.; Moore, C.H. Effects of Physical Attractiveness of the Plaintiff and Defendant in Sexual Harassment Judgments. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1990, 5, 547–562. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, P.G.; Forscher, P.S.; Austin, A.J.; Cox, W.T.L. Long-Term Reduction in Implicit Race Bias: A Prejudice Habit-Breaking Intervention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuper, P.A.; Fisher, W.A. The Role of Sexual Arousal and Sexual Partner Characteristics in HIV + MSM’s Intentions to Engage in Unprotected Sexual Intercourse. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.A.; Sabat, I.E.; Martinez, L.R.; Weaver, K.; Xu, S. A Convenient Solution: Using MTurk To Sample From Hard-To-Reach Populations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCredie, M.N.; Morey, L.C. Who Are the Turkers? A Characterization of MTurk Workers Using the Personality Assessment Inventory. Assessment 2019, 26, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Ward, L.M.; Kroff, S.L.; Davis, E.J.; Holmgren, H.G.; Jensen, A.C.; Erickson, S.E.; Essig, L.W. Contributions of Mainstream Sexual Media Exposure to Sexual Attitudes, Perceived Peer Norms, and Sexual Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landor, A.; Simons, L.G.; Simons, R.L.; Brody, G.H.; Gibbons, F.X. The Role of Religiosity in the Relationship Between Parents, Peers, and Adolescent Risky Sexual Behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, K.A.; Fehring, R.J. The Association of Religiosity, Sexual Education, and Parental Factors with Risky Sexual Behaviors Among Adolescents and Young Adults. J. Relig. Health 2010, 49, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).