Narcissistic Personality Traits and Sexual Satisfaction in Men: The Role of Sexual Self-Esteem

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures and Procedure

2.3. Statistical Analyses

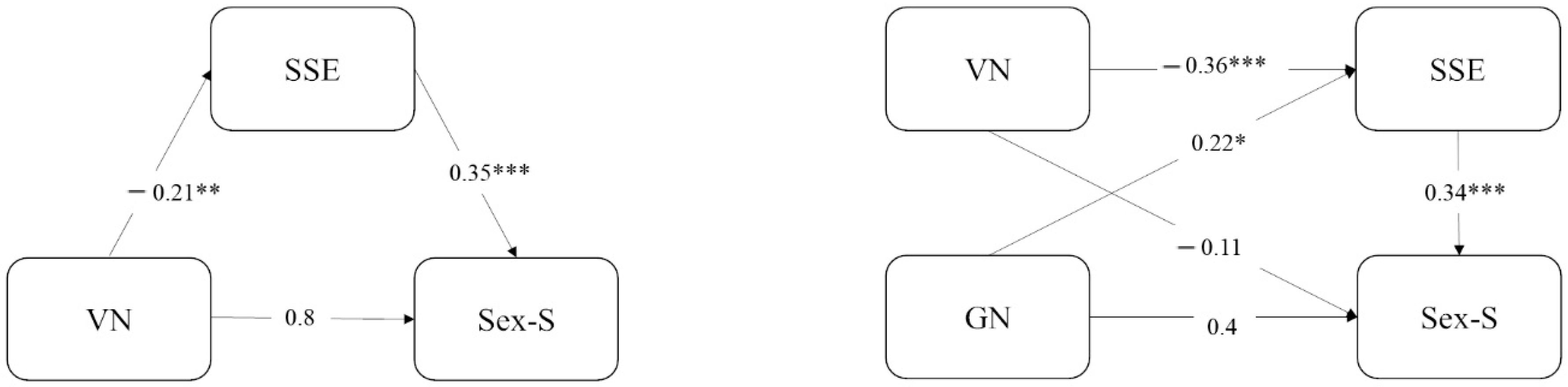

3. Results

4. Discussion

Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Measuring Sexual Health: Conceptual and Practical Considerations and Related Indicators (No. WHO/RHR/10.12); WHO Document Production Services: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haavio-Mannila, E.; Kontula, O. Correlates of Increased Sexual Satisfaction. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1997, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S.; Cate, R.M. Sexual satisfaction and sexual expression as predictors of relationship satisfaction and stability. In The Handbook of Sexuality in Close Relationships; Harvey, J.H., Wenzel, A., Sprecher, S., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Byers, E.S. Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. J. Sex Res. 2005, 42, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, H.-C.; Lorenz, F.O.; Wickrama, K.A.S.; Conger, R.D.; Elder, G.H. Relationships among sexual satisfaction, marital quality, and marital instability at midlife. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McNulty, J.K.; Widman, L. The Implications of Sexual Narcissism for Sexual and Marital Satisfaction. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013, 42, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levy, K.N.; Ellison, W.D.; Reynoso, J.S. A Historical Review of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality. In The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, H. Auto-eroticism: A psychological study. Alienist Neurol. 1898, 19, 260–299. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. On Narcissism: An Introduction; S.E. XXIV; Hogarth: London, UK, 1914; pp. 67–102. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.D.; Lynam, D.R.; Hyatt, C.S.; Campbell, W.K. Controversies in Narcissism. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, A.L.; Ansell, E.B.; Pimentel, C.A.; Cain, N.M.; Wright, A.G.C.; Levy, K.N. Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernberg, O.F. Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical background and diagnostic classifi-cation. In Disorders of Narcissism: Diagnostic, Clinical, and Empirical Implications; Ronningstam, E., Ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, A.L.; Lukowitsky, M.R. Pathological Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ronningstam, E. Narcissistic Personality Disorder: A Current Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2010, 12, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, D.R.; Widiger, T.A. Using the five-factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: An expert con-sensus approach. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001, 110, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D.; Lynam, D.R.; Siedor, L.; Crowe, M.L.; Campbell, W.K. Consensual lay profiles of narcissism and their con-nection to the five-factor narcissism inventory. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, D.B.; Widiger, T.A. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 1326–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Pierro, R.; Di Sarno, M.; Preti, E.; Di Mattei, V.E.; Madeddu, F. The role of identity instability in the relationship be-tween narcissism and emotional empathy. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2018, 35, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, A.L.; Roche, M.J. Narcissistic Grandiosity and Narcissistic Vulnerability. In The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pierro, R.; Costantini, G.; Benzi, I.M.A.; Madeddu, F.; Preti, E. Grandiose and entitled, but still fragile: A network anal-ysis of pathological narcissistic traits. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 140, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D.; Campbell, W.K. The case for using research on trait narcissism as a building block for understanding narcis-sistic personality disorder. Pers. Disord 2010, 3, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.D.; Hoffman, B.J.; Gaughan, E.T.; Gentile, B.; Maples, J.; Keith Campbell, W. Grandiose and vulnerable narcis-sism: A nomological network analysis. J. Pers. 2011, 79, 1013–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.; Donnellan, M.B.; Hopwood, C.J.; Ackerman, R.A. The two faces of Narcissus? An empirical comparison of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.K.; Zivnuska, S.; Kacmar, K.M. Self-perception and life satisfaction. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 139, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmann, E.; Hanke, S.; Bierhoff, H.-W. Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism in Relation to Life Satisfaction, Self-Esteem, and Self-Construal. J. Individ. Differ. 2019, 40, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M.; Piotrowski, J.P.; Maltby, J. Agentic and communal narcissism and satisfaction with life: The mediating role of psychological entitlement and self-esteem. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 52, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, J.D.; Campbell, W.K.; Pilkonis, P.A. Narcissistic personality disorder: Relations with distress and functional im-pairment. Compr. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Widman, L.; McNulty, J.K. Sexual Narcissism and the Perpetration of Sexual Aggression. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2009, 39, 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A. Why do narcissistic individuals engage in sex? Exploring sexual motives as a mediator for sexual satis-faction and function. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 105, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, V.; Reininger, K.M.; Briken, P.; Turner, D. Sexual narcissism and its association with sexual and well-being out-comes. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 152, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Fioravanti, G.; Baldi, V.; Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L. Narcissism, perfectionistic self-presentation, and relationship satisfaction from a dyadic perspective: Narcissism and Relationship Satisfaction. Self Identity 2019, 19, 948–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, D.C.; Yi, J.; Baucom, D.H.; Christensen, A. Infidelity in Couples Seeking Marital Therapy. J. Fam. Psychol. 2005, 19, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foster, J.D.; Shrira, I.; Campbell, W.K. Theoretical models of narcissism, sexuality, and relationship commitment. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2006, 23, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, T.E.; Short, M.B.; Milam, A.C. Narcissism and Internet Pornography Use. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2014, 41, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigler-Hill, V.; Enjaian, B.; Essa, L. The Role of Narcissistic Personality Features in Sexual Aggression. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 32, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A.; Finzi-Dottan, R. Narcissism and Relationship Satisfaction from a Dyadic Perspective: The Mediating Role of Psychological Aggression. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2017, 54, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, W.; Kinrade, C.; Breeden, C.J. Revisiting narcissism and contingent self-esteem: A test of the psychodynamic mask model. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 162, 110026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, E.; Newman, D.A.; Tay, L.; Donnellan, M.B.; Harms, P.D.; Robins, R.W.; Yan, T. Gender differences in narcis-sism: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 261–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wolff, M.; Wells, B.; Ventura-DiPersia, C.; Renson, A.; Grov, C. Measuring sexual orientation: A review and cri-tique of US data collection efforts and implications for health policy. J. Sex Res. 2017, 54, 507–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, W.E., Jr.; Papini, D.R. The Sexuality Scale: An instrument to measure sexual-esteem, sexual-depression, and sexual-preoccupation. J. Sex Res. 1989, 26, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzichristou, D.; Rosen, R.C.; Derogatis, L.R.; Low, W.Y.; Meuleman, E.J.; Sadovsky, R.; Symonds, T. Recommendations for the Clinical Evaluation of Men and Women with Sexual Dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2010, 7, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edershile, E.A.; Simms, L.J.; Wright, A.G.C. A Multivariate Analysis of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory′s Nomological Network. Assessment 2018, 26, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.K.; Bosson, J.K.; Goheen, T.W.; Lakey, C.E.; Kernis, M.H. Do narcissists dislike themselves “deep down inside”? Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, D.D.; Preacher, K.J.; Tormala, Z.L.; Petty, R.E. Mediation Analysis in Social Psychology: Current Practices and New Recommendations. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sarno, M.; Zimmermann, J.; Madeddu, F.; Casini, E.; Di Pierro, R. Shame behind the corner? A daily diary investigation of pathological narcissism. J. Res. Pers. 2020, 85, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizan, Z.; Johar, O. Envy divides the two faces of narcissism. J. Pers. 2012, 80, 1415–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Relationship Status | |

| Single | 67 (31.6) |

| Cohabiting couple | 71 (33.5) |

| Non-cohabiting couple | 74 (34.9) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 166 (78.3) |

| Married | 35 (16.5) |

| Separated/divorced | 9 (4.3) |

| Educational Level | |

| Lower than high school | 9 (4.2) |

| High school degree | 103 (48.6) |

| University degree | 76 (35.8) |

| Post-graduate education | 24 (11.3) |

| Working status | |

| Employed | 137 (64.6) |

| Unemployed | 7 (3.3) |

| Student | 68 (32.1) |

| Dimensions of Sexual Orientation | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sexual Identity | |

| Heterosexual | 188 (88.7) |

| Bisexual | 7 (3.3) |

| Homosexual | 15 (7.1) |

| Other | 2 (0.9) |

| Sexual Attraction | |

| Exclusively to women | 182 (85.8) |

| Predominantly to women more than accidentally to men | 2 (0.9) |

| Predominantly to women only accidentally to men | 8 (3.8) |

| Equally to women and men | 1 (0.5) |

| Predominantly to men more than accidentally to women | 2 (0.9) |

| Predominantly to men only accidentally to women | 6 (2.8) |

| Exclusively to men | 11 (5.2) |

| Sexual Behavior | |

| Exclusively with women | 169 (79.7) |

| Predominantly with women only occasionally with men | 3 (1.4) |

| Equally with women and men | 1 (0.5) |

| Exclusively to men | 15 (7.1) |

| Neither women nor men | 24 (11.3) |

| SSE | Sex-S | VN | GN 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual self-esteem (SSE) | - | 0.36 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.17 * |

| Sexual satisfaction (Sex-S) | - | - | −0.15 * | 0.09 |

| Vulnerable narcissism (VN) | - | - | - | - |

| Grandiose narcissism (GN) | - | - | - | - |

| M | 3.56 | 4.12 | 3.08 | - |

| SD | 0.84 | 1.29 | 0.68 | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anzani, A.; Di Sarno, M.; Di Pierro, R.; Prunas, A. Narcissistic Personality Traits and Sexual Satisfaction in Men: The Role of Sexual Self-Esteem. Sexes 2021, 2, 17-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2010002

Anzani A, Di Sarno M, Di Pierro R, Prunas A. Narcissistic Personality Traits and Sexual Satisfaction in Men: The Role of Sexual Self-Esteem. Sexes. 2021; 2(1):17-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnzani, Annalisa, Marco Di Sarno, Rossella Di Pierro, and Antonio Prunas. 2021. "Narcissistic Personality Traits and Sexual Satisfaction in Men: The Role of Sexual Self-Esteem" Sexes 2, no. 1: 17-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2010002

APA StyleAnzani, A., Di Sarno, M., Di Pierro, R., & Prunas, A. (2021). Narcissistic Personality Traits and Sexual Satisfaction in Men: The Role of Sexual Self-Esteem. Sexes, 2(1), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2010002