Heinrich von Kleist’s Extremely Complex Syntax: How Does It Affect Aesthetic Liking?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses

3. Study 1

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

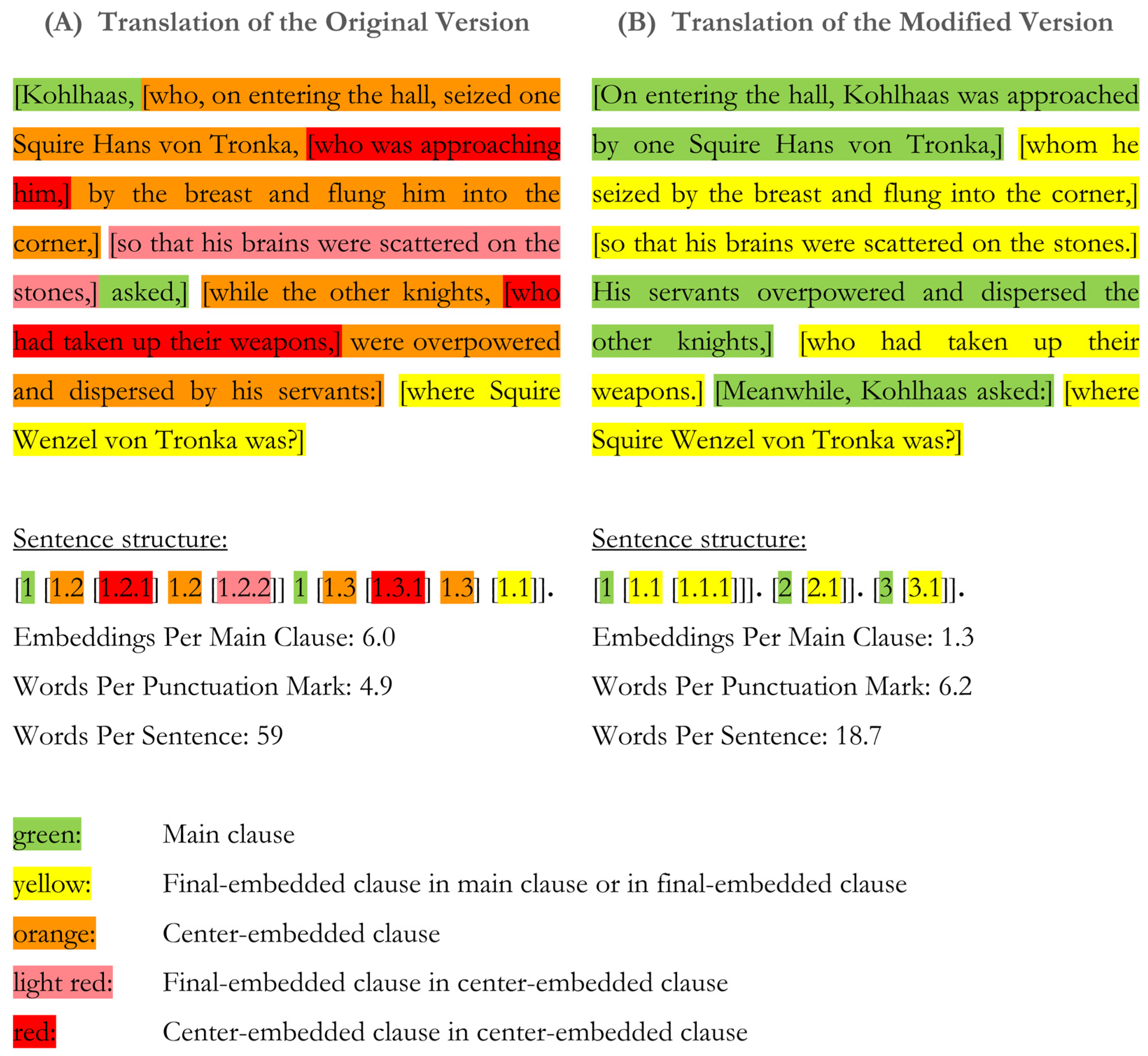

3.1.2. Stimuli

3.1.3. Design

3.1.4. Procedure

3.1.5. Measures

3.1.6. Statistical Analysis

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Reading Times, Text Familiarity, and Author Recognition

3.2.2. Mean Version-Dependent Differences in Ratings Across All Texts

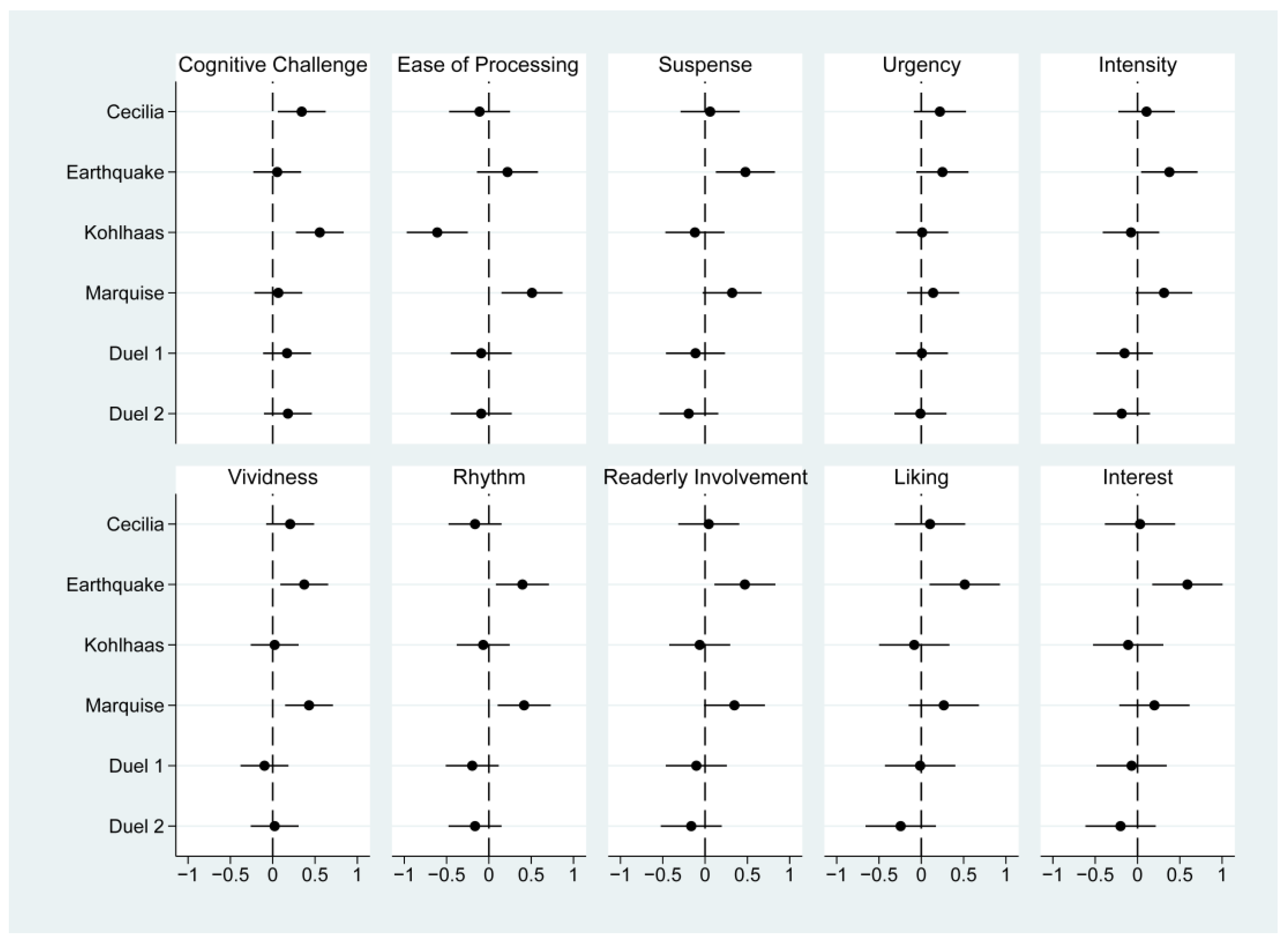

3.2.3. Version-Dependent Differences in Ratings for the Individual Texts

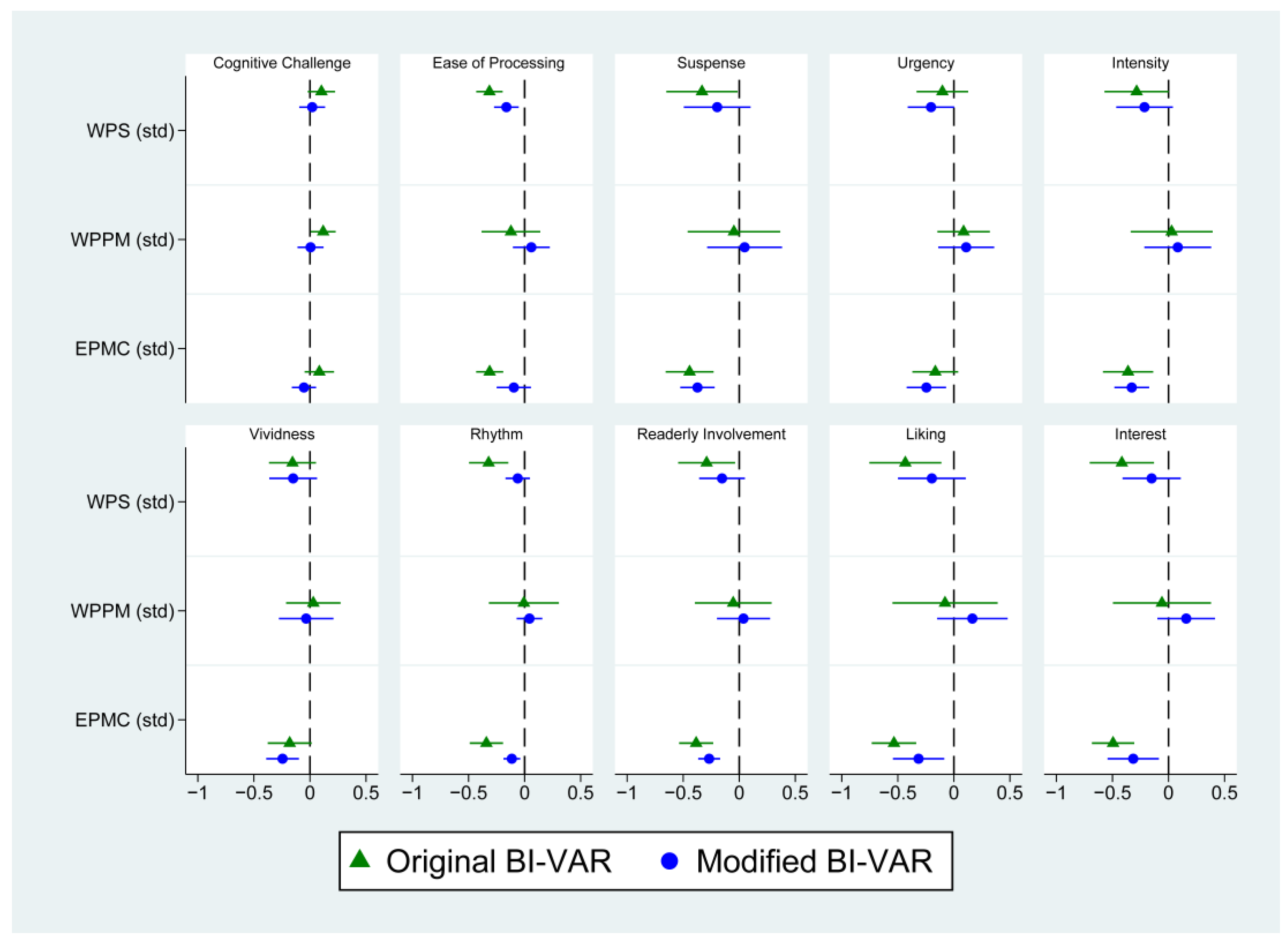

3.2.4. Objective Measures of Syntactic Complexity as Predictors of the Subjective Ratings

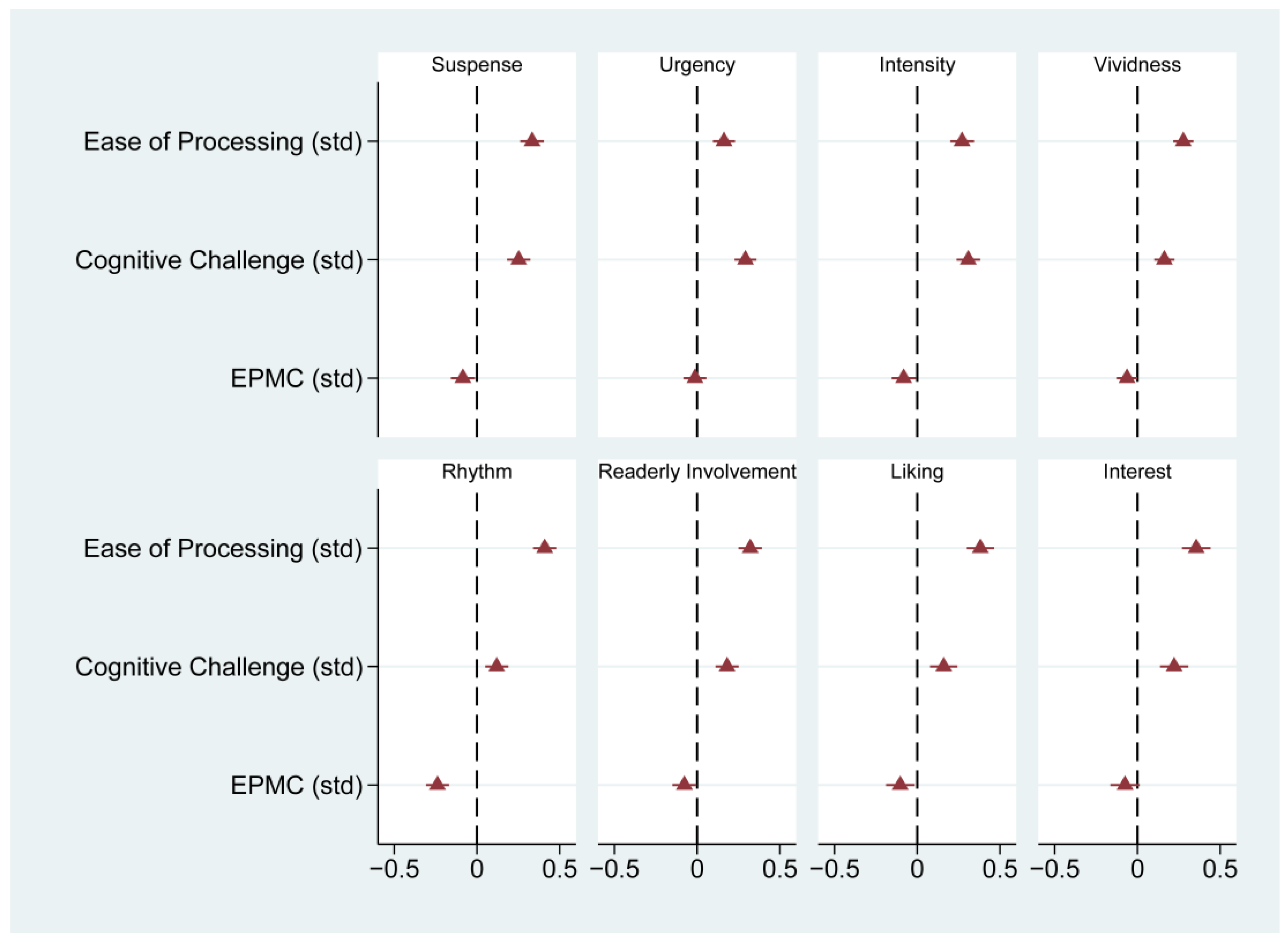

3.2.5. Relations Between Ease of Processing, Cognitive Challenge, and Aesthetic Evaluations

3.3. Summary and Discussion of Study 1

4. Study 2

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Stimuli

4.1.3. Design

4.1.4. Statistical Analysis

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Reading Times, Text Familiarity, and Author Recognition

4.2.2. Version-Dependent Differences Between the Ratings for the Four Texts

4.2.3. Ease of Processing, Cognitive Challenge, and Aesthetic Evaluations

4.2.4. Objective Textual Complexity Versus Subjectively Perceived Fluency

4.2.5. Individual Differences in Relations Between Cognitive Challenge and Aesthetic Evaluations

4.3. Summary and Discussion of Study 2

5. General Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- 1

- Cognitive Challenge, Ease of Processing, and Aesthetic Evaluation Items

| # | Variable | German Wording | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Cognitive Challenge | Wie komplex wirkt der Text auf Sie? | How complex does the text seem to you? |

| 11 | Wie anspruchsvoll fanden Sie die Lektüre des Textes? | How challenging did you find it to read of the text? | |

| 19 | Wie markant ist der Stil der Erzählung? | How distinctive is the style of the narrative? | |

| 21 | Wie sehr weicht der Stil des Textes von normalem Sprachgebrauch ab? | How much does the style of the text deviate from normal usage? | |

| 12 | Ease of Processing | Wie leicht ist der Text zu verstehen? | How easy is it to understand the text? |

| 01 | Suspense | Wie spannend finden Sie die Geschichte? | How exciting do you find the story? |

| 02 | Wie dramatisch finden Sie die Art des Erzählens? | How dramatic do you find the style of narration? | |

| 03 | Wie packend finden Sie die Erzählung? | How gripping do you find the narrative? | |

| 04 | Urgency | Wie temporeich finden Sie die Abfolge der Ereignisse? | How fast-paced do you find the sequence of events? |

| 05 | Wie sehr vermittelt Ihnen das Fortschreiten der Erzählung einen Eindruck von Dringlichkeit? | How much does the progression of the narrative give you a sense of urgency? | |

| 06 | Wie gedrängt ist die Schilderung des Geschehens? | How compressed is the description of the events? | |

| 22 | Intensity | Wie intensiv war das Leseerlebnis für Sie? | How intense was the reading experience for you? |

| 25 | Als wie kraftvoll empfinden Sie die Sprache der Erzählung? | How powerful do you find the language of the narrative? | |

| 26 | Wie stark ist der Eindruck, den der Text bei Ihnen hinterlassen hat? | How strong an impression did the text leave on you? | |

| 07 | Vividness | Wie lebendig treten Ihnen beim Lesen die Figuren bzw. die geschilderten Ereignisse vor Augen? | How vividly do the characters or the events described appear to your mind while reading? |

| 08 | Wie anschaulich ist Ihr Eindruck von den berichteten Ereignissen? | How vivid is your impression of the reported events? | |

| 09 | Wie detailreich finden Sie die Geschichte geschrieben? | How rich in detail do you find the story? | |

| 20 | Rhythm | Wie elegant finden Sie die Erzählung geschrieben? | How elegantly written do you find the story? |

| 23 | Wie rhythmisch finden Sie die Sprache des Textes? | How rhythmic do you find the language of the text? | |

| 27 | Wie fließend finden Sie die Sprache des Textes? | How fluent do you find the language of the text? | |

| 13 | Readerly Involvement | Wie sehr hat die Erzählung Ihre Aufmerksamkeit gefesselt? | How much did the narrative hold your attention? |

| 14 | Wie sehr hatten Sie das Gefühl, beim Lesen in einer anderen Welt gewesen zu sein? | How much did you feel like you were in another world while reading? | |

| 15 | Wie sehr haben Sie sich beim Lesen in die Gefühle und Gedanken der (Haupt-) Figuren hineinversetzt? | How much did you empathize with the feelings and thoughts of the (main) characters while reading? | |

| 16 | Liking | Wie gut gefällt Ihnen der Text? | How much do you like the text? |

| 17 | Wie gern würden Sie die gesamte Erzählung lesen? | How much would you like to read the entire narrative? | |

| 18 | Wie sehr würden Sie den Text einem Freund/einer Freundin empfehlen? | How much would you recommend the text to a friend? | |

| 24 | Interest | Wie interessant finden Sie den Text? | How interesting do you find the text? |

- 2

- Figures

| 1 | The idea of modeling ease of processing and cognitive challenge conjointly as predictors of the aesthetic evaluations was not part of the a priori-design of the two studies reported in this article. It occurred to us only in retrospect. Importantly, the temporal genealogy of these additional analyses of our data does not affect their validity. We therefore report—for the purposes of better readability—all pertinent analyses as parts of one study. |

| 2 | Still, local reading times measured for the immediate context of the optional punctuations did show slightly increased fixation times for the presence vs. absence of optional punctuations in these two studies. |

References

- Admoni, Wladimir G. 1987. Die Entwicklung des Satzbaus der deutschen Literatursprache im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Berlin: Akademie. ISBN 9783050001555. [Google Scholar]

- Alter, Adam L. 2013. The Benefits of Cognitive Disfluency. Current Directions in Psychological Science 22: 437–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angele, Bernhard, Ismael Gutiérrez-Cordero, Manuel Perea, and Ana Marcet. 2024. Reading (,) With and Without Commas. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 77: 1190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglada-Tort, Manuel, Jochen Steffens, and Daniel Müllensiefen. 2019. Names and Titles Matter: The Impact of Linguistic Fluency and the Affect Heuristic on Aesthetic and Value Judgements of Music. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 13: 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, Emmon, Colin Brown, and William Marslen-Wilson. 1986. Crossed and Nested Dependencies in German and Dutch: A Psycholinguistic Study. Language and Cognitive Processes 1: 249–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, Paul B., Ursula M. Staudinger, and Ulman Lindenberger. 1999. Lifespan Psychology: Theory and Application to Intellectual Functioning. Annual Review of Psychology 50: 471–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfi, Amy M., Edward A. Vessel, and G. Gabrielle Starr. 2018. Individual Ratings of Vividness Predict Aesthetic Appeal in Poetry. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 12: 341–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belke, Benno, Helmut Leder, Tilo Strobach, and Claus Christian Carbon. 2010. Cognitive Fluency: High-level Processing Dynamics in Art Appreciation. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 4: 214–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlyne, Daniel E. 1971. Aesthetics and Psychobiology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. ISBN 9780390086709. [Google Scholar]

- Birney, Damian P., and Robert J. Sternberg. 2011. The Development of Cognitive Abilities. In Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook. Edited by Marc H. Bornstein and Michael E. Lamb. London: Psychology Press, pp. 353–88. ISBN 978-1848726116. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, Heinrich. 1899. Der Satzbau bei Heinrich von Kleist. Zeitschrift für den deutschen Unterricht 13: 713–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carrière, Mathieu. 1984. Für eine Literatur des Krieges. Frankfurt/Basel: Stroemfeld. ISBN 9783878771517. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262530071. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jonathan. 2001. Defining Identification: A Theoretical Look at the Identification of Audiences With Media Characters. Mass Communication and Society 4: 245–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. 1985. On Literary Composition. In Dionysius of Halicarnassus: Critical Essays. Translated by Stephen Usher. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, vol. 2, ISBN 9780674995130. [Google Scholar]

- Fayn, Kirill, Carolyn MacCann, Niko Tiliopoulos, and Paul J. Silvia. 2015a. Aesthetic Emotions and Aesthetic People: Openness Predicts Sensitivity to Novelty in the Experiences of Interest and Pleasure. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayn, Kirill, Niko Tiliopoulos, and Carolyn MacCann. 2015b. Interest in Truth Versus Beauty: Intellect and Openness Reflect Different Pathways Towards Interest. Personality and Individual Differences 81: 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayn, Kirill, Paul J. Silvia, Carolyn MacCann, and Niko Tiliopoulos. 2017. Interested in Different Things or in Different Ways? Exploring the Engagement Distinction Between Openness and Intellect. Journal of Individual Differences 38: 265–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayn, Kirill, Paul J. Silvia, Egon Dejonckheere, Stijn Verdonck, and Peter Kuppens. 2019. Confused or Curious? Openness/intellect Predicts More Positive Interest-Confusion Relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 117: 1016–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, Michael, Gernot Gerger, and Helmut Leder. 2015. Everything’s Relative? Relative Differences in Processing Fluency and the Effects on Liking. PLoS ONE 10: e0135944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Forster, Michael, Helmut Leder, and Ulrich Ansorge. 2013. It Felt Fluent, and I Liked It: Subjective Feeling of Fluency Rather Than Objective Fluency Determines Liking. Emotion 13: 280–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, Lyn, and Janet Dean Fodor. 1978. The Sausage Machine: A New Two-Stage Parsing Model. Cognition 6: 291–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, Albert. 1904. Zu Heinrich von Kleists Stil. Studien zur vergleichenden Literaturgeschichte 4: 440–65. [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof, G. John, Kristopher J. Preacher, and Michael J. Zyphur. 2014. Reliability Estimation in a Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis Framework. Psychological Methods 19: 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, Edward. 1998. Linguistic Complexity: Locality of Syntactic Dependencies. Cognition 68: 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giora, Rachel, Ofer Fein, Ann Kronrod, Idit Elnatan, Noa Shuval, and Adi Zur. 2004. Weapons of Mass Distraction: Optimal Innovation and Pleasure Ratings. Metaphor and Symbol 19: 115–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, Laura K. M., and Jan R. Landwehr. 2015. A Dual-Process Perspective on Fluency-Based Aesthetics: The Pleasure-Interest Model of Aesthetic Liking. Personality and Social Psychology Review 19: 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbrecht, Hans-Ulrich, and Friederike Knüpling, eds. 2004. Kleist Revisited. Paderborn: Fink. ISBN 9783846754689. [Google Scholar]

- Güçlütürk, Yağmur, Richard H. A. H. Jacobs, and Rob van Lier. 2016. Liking Versus Complexity: Decomposing the Inverted U-Curve. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 10: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huron, David Brian. 2006. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262582780. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Arthur M. 2014. Towards a Neurocognitive Poetics Model of Literary Reading. In Towards a Cognitive Neuroscience of Natural Language Use. Edited by Roel M. Willems. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 135–95. ISBN 9781107323667. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, Fred. 2007. Constraints on Multiple Center-Embedding of Clauses. Journal of Linguistics 43: 365–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausnitzer, Ralf. 2012. “(die Schriftgelehrten mögen ihn erklären)”: Zum Kommagebrauch des Heinrich von Kleist. In Die Poesie der Zeichensetzung: Studien zur Stilistik der lnterpunktion. Edited by Alexander Nebrig and Carlos Spoerhase. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 203–38. ISBN 9783034310000. [Google Scholar]

- Knoop, Christine A., Valentin Wagner, Thomas Jacobsen, and Winfried Menninghaus. 2016. Mapping the Aesthetic Space of Literature From “Below”. Poetics 56: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, Willard, and David Burns. 1977. Sentence Comprehension and Memory for Embedded Structure. Memory & Cognition 5: 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kwan Min. 2004. Presence, Explicated. Communication Theory 14: 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuuchi, Michiru, Jörg Bahlmann, Alfred Anwander, and Angela D. Friederici. 2009. Segregating the Core Computational Faculty of Human Language From Working Memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106: 8362–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, John J., Emilio Ferrer-Caja, Fumiaki Hamagami, and Richard W. Woodcock. 2002. Comparative Longitudinal Structural Analyses of the Growth and Decline of Multiple Intellectual Abilities Over the Life Span. Developmental Psychology 38: 115–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medford, Emma, and Sarah P. McGeown. 2012. The Influence of Personality Characteristics on Children’s Intrinsic Reading Motivation. Learning and Individual Differences 22: 786–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninghaus, Winfried. 2009. “Ein Gefühl der Beförderung des Lebens”: Kants Reformulierung des Topos lebhafter Vorstellung. In Vita aesthetica: Szenarien ästhetischer Lebendigkeit. Edited by Armen Avanessian, Winfried Menninghaus and Jan Völker. Zürich/Berlin: Diaphanes, pp. 77–94. ISBN 9783037340752. [Google Scholar]

- Menninghaus, Winfried, Isabel C. Bohrn, Christine A. Knoop, Sonja A. Kotz, Wolff. Schlotz, and Arthur M. Jacobs. 2015. Rhetorical Features Facilitate Prosodic Processing While Handicapping Ease of Semantic Comprehension. Cognition 143: 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninghaus, Winfried, Isabel. C. Bohrn, Ulman Altmann, Oliver Lubrich, and Arthur M. Jacobs. 2014. Sounds Funny? Humor Effects of Phonological and Prosodic Figures of Speech. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 8: 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninghaus, Winfried, Valentin Wagner, Eugen Wassiliwizky, Thomas Jacobsen, and Christine A. Knoop. 2017. The Emotional and Aesthetic Powers of Parallelistic Diction. Poetics 63: 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninghaus, Winfried, Valentin Wagner, Ines Schindler, Christine A. Knoop, Stefan Blohm, Klaus Frieler, and Mathias Scharinger. 2023. Parallelisms and Deviations: Two Fundamentals of an Aesthetics of Poetic Diction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 379: 20220424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, Leonard B. 1961. Emotion and Meaning in Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226521398. [Google Scholar]

- Miall, David S., and Don Kuiken. 1994. Foregrounding, Defamiliarization, and Affect: Response to Literary Stories. Poetics 22: 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebrig, Alexander, and Carlos Spoerhase. 2012. Für eine Stilistik der Interpunktion. In Die Poesie der Zeichensetzung: Studien zur Stilistik der lnterpunktion. Edited by Alexander Nebrig and Carlos Spoerhase. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 11–31. ISBN 9783034310000. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeier, Christian, Sonja A. Kotz, Sarah Jessen, Tim Raettig, Martin von Koppenfels, and Winfried Menninghaus. 2016. Aesthetic Appreciation of Poetry Correlates With Ease of Processing in Event-Related Potentials. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 16: 362–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, Delroy L., Richard W. Robins, Kali H. Trzesniewski, and Jessica L. Tracy. 2004. Two Replicable Suppressor Situations in Personality Research. Multivariate Behavioral Research 39: 303–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, Martin J., and Roger P. G. van Gompel. 2006. Syntactic Parsing. In Handbook of Psycholinguistics, 3rd ed. Edited by Matthew J. Traxler and Morton A. Gernsbacher. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, pp. 455–503. ISBN 9780123693747. [Google Scholar]

- Reber, Rolf, Norbert Schwarz, and Piotr Winkielman. 2004. Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver’s Processing Experience? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 8: 364–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, Friedrich. 2001. On the Study of Greek Poetry. Translated by Stuart Barnett. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791448298. [Google Scholar]

- Sembdner, Helmut. 1994. Kleists Interpunktion. In In Sachen Kleist, Beiträge zur Forschung, 3rd expanded ed. Munich: Carl Hanser, pp. 149–75. ISBN 9783446176980. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, Paul J. 2005. What is Interesting? Exploring the Appraisal Structure of Interest. Emotion 5: 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, Paul J. 2007. Knowledge-based Assessment of Expertise in the Arts: Exploring Aesthetic Fluency. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 1: 247–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, Paul J. 2010. Confusion and Interest: The Role of Knowledge Emotions in Aesthetic Experience. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 4: 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, Paul J. 2013. Interested Experts, Confused Novices: Art Expertise and the Knowledge Emotions. Empirical Studies of the Arts 31: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, Paul J., and Christopher Berg. 2011. Finding Movies Interesting: How Appraisals and Expertise Influence the Aesthetic Experience of Film. Empirical Studies of the Arts 29: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, Paul J., Robert A. Henson, and Jonathan L. Templin. 2009. Are the Sources of Interest the Same for Everyone? Using Multilevel Mixture Models to Explore Individual Differences in Appraisal Structures. Cognition & Emotion 23: 1389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenzel, Jürgen. 1966. Zeichensetzung: Stiluntersuchungen an deutscher Prosadichtung. Palaestra 241. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow, Elizabeth A. L., Matthew C. Shake, Joseph R. Miles, Kenton Lee, Xuefei Gao, and George McConkie. 2010. Pay Now or Pay Later: Aging and the Role of Boundary Salience in Self-Regulation of Conceptual Integration in Sentence Processing. Psychology and Aging 25: 168–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, Matthew J., Liv J. Hoversten, and Trevor A. Brothers. 2018. Sentence Processing and Interpretation in Monolinguals and Bilinguals: Classical and Contemporary Approaches. In The Handbook of Psycholinguistics. Edited by Eva M. Fernández and Helen Smith Cairns. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 320–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hellingrath, N. 1911. Pindar-Übertragungen von Hölderlin: Prolegomena zu einer Erstausgabe. Munich: Diederichs. [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist, Heinrich. 1989. Sämtliche Werke. Berliner Ausgabe. Die Marquise von O…. Edited by Roland Reuß and Peter Staengle. Frankfurt/Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern, vol. II/2, ISBN 9783878773481. [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist, Heinrich. 1990. Sämtliche Werke. Berliner Ausgabe. Michael Kohlhass (1808). Edited by Roland Reuß and Peter Staengle. Frankfurt/Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern, vol. II/1, ISBN 9783878773481. [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist, Heinrich. 1993. Sämtliche Werke. Brandenburger Ausgabe. Das Erdbeben in Chili. Edited by Roland Reuß and Peter Staengle. Frankfurt/Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern, vol. II/3, ISBN 9783878773504. [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist, Heinrich. 1994. Sämtliche Werke. Brandenburger Ausgabe. Der Zweikampf. Edited by Roland Reuß and Peter Staengle. Frankfurt/Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern, vol. II/6, ISBN 9783878773566. [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist, Heinrich. 1997. Sämtliche Werke. Brandenburger Ausgabe. Das Bettelweib von Locarno; Der Findling; Die heilige Cäcilie, oder, Die Gewalt der Musik. Edited by Roland Reuß and Peter Staengle. Frankfurt/Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern, vol. II/5, ISBN 9783878773542. [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist, Heinrich. 2019. Michael Kohlhaas. In Tales From the German, Comprising Specimens From the Most Celebrated Authors. Edited by John Oxenford and C. A. Feiling. Translated by John Oxenford. Sydney: Wentworth Press, pp. 165–230. ISBN 978-1103095469. [Google Scholar]

- Wallot, Sebastian, and Winfried Menninghaus. 2018. Ambiguity Effects of Rhyme and Meter. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 44: 1947–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, Jacob, David A. Kenny, and Charles M. Judd. 2014. Statistical Power and Optimal Design in Experiments in Which Samples of Participants Respond to Samples of Stimuli. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 143: 2020–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkielman, Piotr, and John T. Cacioppo. 2001. Mind at Ease Puts a Smile on the Face: Psychophysiological Evidence That Processing Facilitation Leads to Positive Affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yngve, Victor H. 1960. A Model and an Hypothesis for Language Structure. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 104: 444–66. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/985230 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Zillmann, Dolf. 1996. The Psychology of Suspense in Dramatic Exposition. In Suspense: Conceptualizations, Theoretical Analyses, and Empirical Explorations. Edited by Peter Vorderer, Hans Jürgen Wulff and Mike Friedrichsen. Hillsdale: Erlbaum, pp. 199–231. ISBN 9780805819663. [Google Scholar]

| Words per Sentence | Words per Punctuation Mark | Embeddings per Main Clause | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | M | Δ | O | M | Δ | O | M | Δ | |

| Text | |||||||||

| Cecilia | 59.5 | 26.5 | 33.0 | 4.5 | 8.0 | −3.5 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| Earthquake | 36.1 | 20.6 | 15.5 | 5.3 | 7.6 | −2.3 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Kohlhaas | 69.7 | 17.5 | 52.2 | 3.9 | 7.0 | −3.1 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| Marquise | 35.6 | 27.2 | 8.4 | 4.2 | 7.2 | −3.0 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Duel 1 | 77.3 | 25.3 | 52.0 | 5.3 | 10.2 | −4.9 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| Duel 2 | 56.4 | 27.4 | 29.0 | 4.9 | 10.2 | −5.3 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 1.6 |

| Summary statistics | |||||||||

| Mean | 55.8 | 24.1 | 31.7 | 4.7 | 8.4 | −3.7 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| Range | 41.7 | 9.9 | 43.8 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| Variable | Kleist Experience | General Enjoyment of Reading Narratives | Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease Slope | Challenge Slope | Ease Slope | Challenge Slope | Ease Slope | Challenge Slope | |

| Suspense | −0.004 | 0.11 ** | 0.04 | 0.10 ** | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| Urgency | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Intensity | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.09 ** | 0.03 |

| Vividness | −0.02 | 0.09 * | −0.004 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.07 * |

| Rhythm | −0.06 | 0.13 ** | 0.03 | 0.11 ** | −0.04 | 0.08 * |

| Readerly Involvement | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.08 * | −0.11 ** | 0.08 * |

| Liking | −0.06 | 0.15 ** | 0.01 | 0.18 *** | −0.06 | 0.15 *** |

| Interest | −0.06 | 0.11 * | 0.01 | 0.16 *** | −0.08 | 0.09 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menninghaus, W.; Kegel, V.; Fayn, K.; Schlotz, W. Heinrich von Kleist’s Extremely Complex Syntax: How Does It Affect Aesthetic Liking? Literature 2025, 5, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature5040025

Menninghaus W, Kegel V, Fayn K, Schlotz W. Heinrich von Kleist’s Extremely Complex Syntax: How Does It Affect Aesthetic Liking? Literature. 2025; 5(4):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature5040025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenninghaus, Winfried, Vanessa Kegel, Kirill Fayn, and Wolff Schlotz. 2025. "Heinrich von Kleist’s Extremely Complex Syntax: How Does It Affect Aesthetic Liking?" Literature 5, no. 4: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature5040025

APA StyleMenninghaus, W., Kegel, V., Fayn, K., & Schlotz, W. (2025). Heinrich von Kleist’s Extremely Complex Syntax: How Does It Affect Aesthetic Liking? Literature, 5(4), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature5040025