Reconstructing Childhood via Reimagined Memories: Life Writing in Children’s Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cognitive Literary Studies, Life Writing, and the Archival Study of Creative Writing Processes

I think that our gradings of reality and fiction are rather like our bipedal locomotion—learnt naturally, our second nature—but when analysed by roboticists or literary critics found to be dismayingly complex and subtle. Nevertheless, we persist in remaining upright and walking about.

3. Reconstructive Memory

4. The Paper Traces of Mental Time Travel: Roald Dahl, David Almond, and Jacqueline Woodson

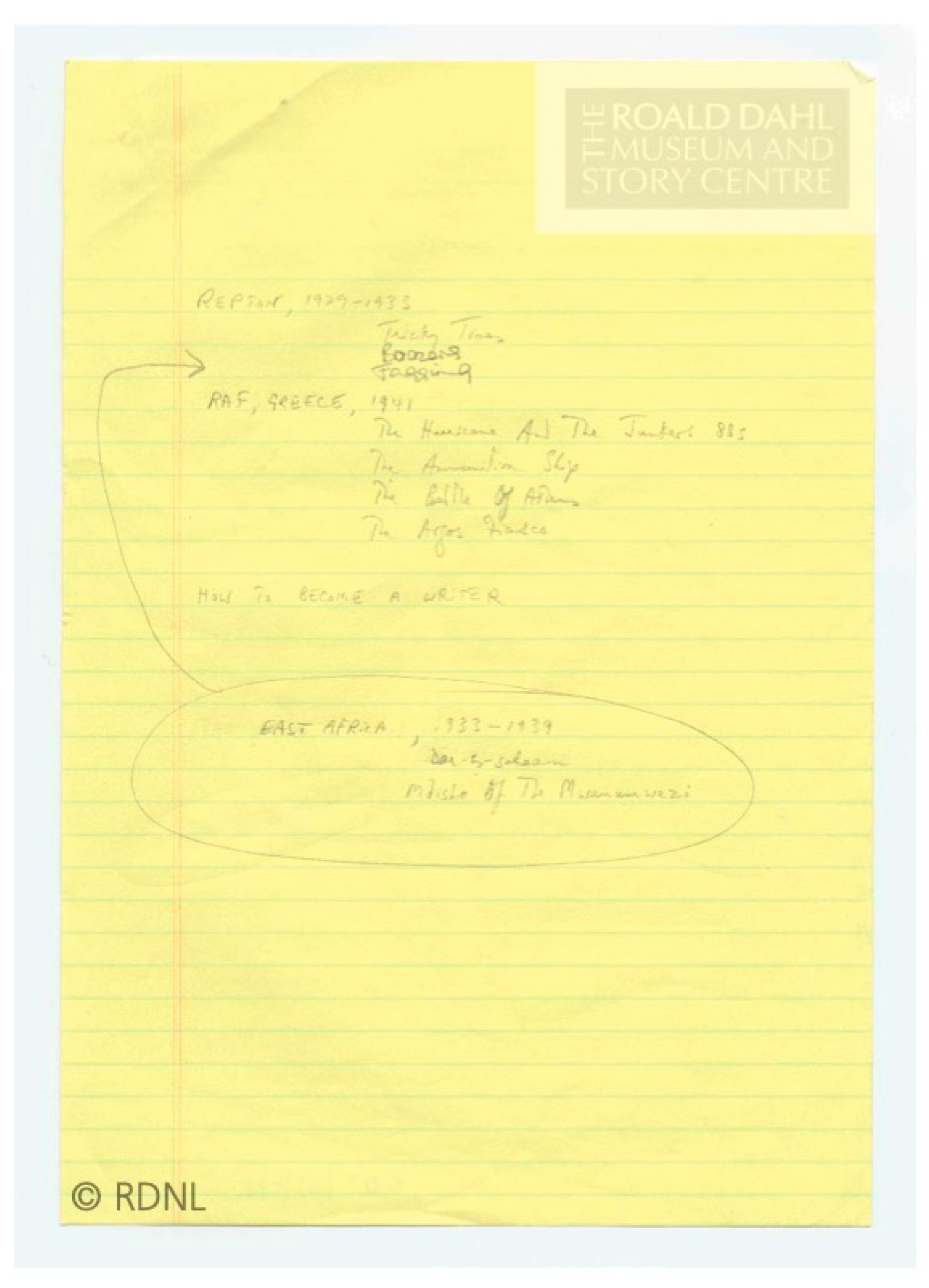

4.1. Roald Dahl’s Boy: “Skim Them off the Top of My Consciousness and Write Them Down”

This is not an autobiography. I would never write a history of myself. On the other hand, throughout my young days at school and just afterwards a number of things happened to me that I have never forgotten (…) I didn’t have to search for any of them. All I had to do was skim them off the top of my consciousness and write them down. Some are funny. Some are painful. Some are unpleasant. I suppose that it why I have always remembered them so vividly. All are true.([1984] 2016, n. pag.)

4.2. David Almond’s Counting Stars: A “Memory Quilt”

I was living on the dole in Suffolk when I wrote the first of the stories in Counting Stars. It was a bitterly cold winter. I wore a hat and scarf as I wrote at a table in a little room overlooking frosty farmland. The story seemed to come from nowhere. I remember writing the first words: “For a long time after Helen died, Mam used to pull my shoulders forward, kiss me, and slip her fingers beneath my shoulder blades and tell me, This is where your wings were…” My mother did do this when I was a boy. I could feel her fingers as I wrote. I could hear her voice. I knew the story was about my sister, Barbara, who died when I was a boy. But in that early version, I didn’t dare to write her proper name.(2000, p. 199)

4.3. Jacqueline Woodson: Memory as a “Mixed Bag”

5. Conclusions: Reconstructing Childhood via Reimagined Memories

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almond, David. 1982–2000. David Almond Archive. Seven Stories. Newcastle: The National Centre for Children’s Books. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, David. 2000. Counting Stars. Hodder Children’s Books. London: Hachette Children’s Group. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, David. 2020. Interview with Vanessa Joosen for the ERC Project Constructing Age for Young Readers. Available online: https://cafyr.uantwerpen.be/en/interview-with-david-almond/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Arnavas, Francesca. 2021. Lewis Carroll’s “Alice” and Cognitive Narratology: Author, Reader, and Characters. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, Mieke, Jonathan V. Crewe, and Leo Spitzer, eds. 1999. Acts of Memory: Cultural Recall in the Present. Hannover: Dartmouth College. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaerts, Lars, and Dirk Van Hulle. 2013. Narrative across Versions: Narratology Meets Genetic Criticism. Poetics Today 34: 281–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, Marco. 2014. Supersizing Narrative Theory: On Intention, Material Agency, and Extended Mind-Workers. Style 48: 349–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, Robin. 2020. ‘You Do It!’: Going-to-Bed Books and the Scripts of Children’s Literature. PMLA 135: 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Lois. 2022. ‘For She Was an Independent Woman, or Nearly, Anyway’: The Sexualisation of Neo-Victorian Girls in Philip Pullman’s Sally Lockhart Series. International Research in Children’s Literature 15: 152–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Aidan. 2001. Anne Frank’s Pen. In Reading Talk. Woodchester: Thimble Press, pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, Kat. 2019. Jacqueline Woodson Transformed Children’s Literature. The New York Times, September 19. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/19/magazine/jacqueline-woodson-red-at-the-bone.html (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Coghlan, Valerie. 2014. ‘A sense sublime’: Religious Resonances in the Works of David Almond. In David Almond. Edited by Rosemary Ross Johnston. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Roald. 1984–1988. The Roald Dahl Story Centre and Museum Archive. Great Missenden: The Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Roald. 2016. Boy. Puffin Books. London: Penguin Random House. First published 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Andrea. 2021. Recognition Plots and Intercultural Encounters in Aidan Chambers’ Dance on My Grave. International Journal of Young Adult Literature 2: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Biasi, Pierre-Marc, and Ingrid Wassenaar. 1996. What Is a Literary Draft? Toward a Functional Typology of Genetic Documentation. Yale French Studies 89: 26–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brigard, Felipe. 2017. Memory and Imagination. In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Memory. Edited by Sven Bernecker and Kourken Michaelian. London: Routledge, pp. 127–40. [Google Scholar]

- De Brigard, Felipe, Sharda Umanath, and Muireann Irish. 2022. Rethinking the Distinction between Episodic and Semantic Memory: Insights from the Past, Present, and Future. Memory & Cognition 50: 459–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debray-Genette, Raymonde. 1977. Génétique et Poétique: Esquisse de Méthode. Littérature 28: 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppman, Jed, Daniel Ferrer, and Michael Groden, eds. 2004. Introduction. In Genetic Criticism: Texts and Avant-Textes. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, Carole. 2014. ‘They thought we had disappeared, and they were wrong’: The Depiction of the Working Class in David Almond’s Novels. In David Almond. Edited by Rosemary Ross Johnston. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 124–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fernyhough, Charles. 2012. Pieces of Light: How the New Science of Memory Illuminates the Stories We Tell about Our Pasts. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, Daniel. 2023. Genetic Joyce: Manuscripts and the Dynamics of Creation. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, Ronald A., Thomas B. Ward, and Steven M. Smith. 1992. Creative Cognition: Theory, Research, and Applications. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds, Adam. 2015. Writing Real People. In On Life-Writing. Edited by Zachary Leader. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Freiman, Marcelle. 2015. A ‘Cognitive Turn’ in Creative Writing—Cognition, Body, and Imagination. New Writing: The International Journal for the Practice and Theory of Creative Writing 12: 127–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genette, Gérard. 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrans, Philip. 2014. The Measure of Madness. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsdóttir, Gunnthórunn. 2003. Borderlines: Autobiography and Fiction in Postmodern Life Writing. Amsterdam: Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, Faye. 2022. Charles Chesnutt, Rhetorical Passing, and the Flesh-and-Blood Author: A Case for Considering Authorial Intention. Narrative 30: 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Julie. 2015. Theories of Memory and the Imaginative Force of Fiction. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Memory Studies. Edited by Siobhan Kattago. London: Routledge, pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Roy. 1989. How Does Writing Restructure Thought? Language and Communication 9: 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, David. 2009. Cognitive Narratology. In Handbook of Narratology. Edited by Peter Hühn, John Pier, Wolf Schmid and Jörg Schönert. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hollindale, Peter. 2001. Signs of Childness in Children’s Books. Jackson: Thimble Press. First published 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, Daniel D., and Erik Myin. 2017. Evolving Enactivism: Basic Minds Meet Content. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Rosemary Ross. 2014. Introduction: David Almond and Mystical Realism. In David Almond. Edited by Rosemary Ross Johnston. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Joosen, Vanessa. 2017. The Genetic Study of Children’s Literature. In The Edinburgh Companion to Children’s Literature. Edited by Clémentine Beauvais and Maria Nikolajeva. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Joosen, Vanessa. 2022. Hoe Oud Is Jong? Leeftijd in Jeugdliteratuur. Borgerhout: Letterwerk. [Google Scholar]

- Joosen, Vanessa. 2023. Counting Stars, discounting years? Life writing and memory studies. In Age in David Almond’s Oeuvre: A Multi-Method Approach to Studying Age and the Life Course in Children’s Literature. Edited by Vanessa Joosen Michelle Anya Anjirbag, Leander Duthoy, Lindsey Geybels, Frauke Pauwels and Emma-Louise Silva. New York: Routledge, pp. 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- Josselyn, Sheena A., and Susumu Tonegawa. 2020. Memory Engrams: Recalling the Past and Imagining the Future. Science 367: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, Kenneth. 2011. The Child, the Scholar, and the Children’s Literature Archive. The Lion and the Unicorn 35: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Helen. 2022. ‘Children My Age Should Be Reading Books Like Journey to Jo’burg’: Patterns of Anti-Racist Reading in Archived Reader Responses. International Research in Children’s Literature 15: 264–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, Karin. 2023. Tracing Creativity? Genetic Narratology in Dialogue with Cognitive Approaches to Literature. Wuppertal: Narratological Colloquium of the Centre for Narrative Research, University of Wuppertal. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, Don. 2006. David Almond: Memory and Magic. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leader, Zachary. 2015. Introduction. In On Life-Writing. Edited by Zachary Leader. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mather, Mara. 2010. Aging and Cognition. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 1: 346–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKie, Kristopher, and Lucy Pearson. 2019. Seven Stories, le Centre national du livre pour enfants au Royaume-Uni. Écritures Jeunesses. Genesis 48: 153–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, William. 2002. Review of Counting Stars. School Library Journal 48. [Google Scholar]

- Menary, Richard. 2007. Writing as Thinking. Language Sciences 29: 621–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, Kourken. 2016. Mental Time Travel: Episodic Memory and Our Knowledge of the Personal Past. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Emily. 2014. Unpacking the Archive: Value, Pricing, and the Letter-Writing Campaign of Dr. Lena Y. de Grummond. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 39: 551–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbantian, Suzanne. 1994. Aesthetic Autobiography. Basingstoke: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Nalbantian, Suzanne. 2003. Memory in Literature: From Rousseau to Neuroscience. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, Chi T., Elisa S. Buchberger, Phuc T. U. Nguyen, Nora S. Newcombe, and Markus Werkle-Bergner. 2024. Building a Cumulative Science of Memory Development. Developmental Review 72: 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolajeva, Maria. 2018. What is it Like to be a Child? Childness in the Age of Neuroscience. Children’s Literature in Education 50: 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otis, Laura. 2022. The Role of Multimodal Imagery in Life Writing. SubStance 51: 115–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsent, Pat. 2012. ‘The Problem of School’: Roald Dahl and Education. In Roald Dahl. Edited by Ann Alston and Catherine Butler. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Kimberley, Tom Schofield, and Diego Trujillo-Pisanty. 2019. Children’s Magical Realism for New Spatial Interactions: Augmented Reality and the David Almond Archives. Children’s Literature in Education 51: 502–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Jacqueline. 1993. The Case of Peter Pan or the Impossibility of Children’s Fiction. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. First published 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, Joshua. 2022. Becoming You: Are You the Same Person You Were When You Were a Child? The New Yorker. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/10/10/are-you-the-same-person-you-used-to-be-life-is-hard-the-origins-of-you (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Sander, Myriam C., Yana Fandakova, and Markus Werkle-Bergner. 2021. Effects of Age Differences in Memory Formation on Neural Mechanisms of Consolidation and Retrieval. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 116: 135–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Eppler, Karen. 2013. In the Archives of Childhood. In The Children’s Table: Childhood Studies and the Humanities. Edited by Anna Mae Duane. Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, pp. 213–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schacter, Daniel L. 2021. The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. New York: Mariner Books. First published 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schwalm, Helga. 2014. Autobiography. In Handbook of Narratology, 2nd ed. Edited by Peter Hühn Jan Christoph Meister, John Pier and Wolf Schmid. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Carole. 2012. Roald Dahl and Quentin Blake. In Roald Dahl. Edited by Ann Alston and Catherine Butler. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 160–75. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Emma-Louise. 2022. Cognitive Narratology and the 4Es: Memorial Fabulation in David Almond’s My Name is Mina. Age Culture, Humanities 6: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Emma-Louise. 2023. Modernist Minds: Materialities of the Mental in the Works of James Joyce. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock, Donald, ed. 2017. Love from Boy: Roald Dahl’s Letters to His Mother. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, John. 2010. Observer Perspective and Acentred Memory: Some Puzzles About Point of View in Personal Memory. Philosophical Studies 148: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickell, Kathryn, and David Almond. 2017. Kathryn Tickell, David Almond, Words and Music. Available online: https://www.kathryntickell.com/biography/history (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Torres, Julia. 2024. An Educator Guide to Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming. New York: Penguin Young Readers School & Library, Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving, Endel. 2002. Episodic Memory: From Mind to Brain. Annual Review of Psychology 53: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hulle, Dirk. 2014. Modern Manuscripts. The Extended Mind and Creative Undoing from Darwin to Beckett and Beyond. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hulle, Dirk. 2022. Genetic Criticism: Tracing Creativity in Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Lierop-Debrauwer, Helma. 2021a. Beyond Boundaries. Authorship and Readership in Life Writing: Introduction. The European Journal of Life Writing 10: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lierop-Debrauwer, Helma. 2021b. Voice and Silence in Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming. European Journal of Life Writing 10: 102–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Erica. 2000. Vivid Bedtime Stories for Young and Old Alike. The Times, November 15. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, Alison. 2017. Re-Memorying: A New Phenomenological Methodology in Children’s Literature Studies. In The Edinburgh Companion to Children’s Literature. Edited by Clémentine Beauvais and Maria Nikolajeva. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 136–49. [Google Scholar]

- Woodson, Jacqueline. 1980–2021. Jacqueline Woodson Papers. James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Available online: https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/resources/11958 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Woodson, Jacqueline. 1998. Who Can Tell My Story. Horn Book Magazine, January/February, n. pag. Available online: https://www.hbook.com/story/who-can-tell-my-story (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Woodson, Jacqueline. 2014a. Brown Girl Dreaming. London: Puffin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Woodson, Jacqueline. 2014b. “Jacqueline Woodson: I Don’t Want Anyone to Feel Invisible”. Interview with Michelle Dean. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/nov/25/jacqueline-woodson-national-book-awards-invisible (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Zunshine, Lisa. 2022a. How Memories Become Literature. SubStance 51: 92–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunshine, Lisa. 2022b. Introduction: Life Writing and Cognition. SubStance 51: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, E.-L. Reconstructing Childhood via Reimagined Memories: Life Writing in Children’s Literature. Literature 2024, 4, 214-233. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature4040016

Silva E-L. Reconstructing Childhood via Reimagined Memories: Life Writing in Children’s Literature. Literature. 2024; 4(4):214-233. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature4040016

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Emma-Louise. 2024. "Reconstructing Childhood via Reimagined Memories: Life Writing in Children’s Literature" Literature 4, no. 4: 214-233. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature4040016

APA StyleSilva, E.-L. (2024). Reconstructing Childhood via Reimagined Memories: Life Writing in Children’s Literature. Literature, 4(4), 214-233. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature4040016