Abstract

More and more informational picturebooks on environmental topics have been published in recent years, many focusing on the inevitable climate change. Conversely, there is still a tendency in contemporary picturebooks to represent the climate traditionally, irrespective of actual climate change. A particularly interesting case is the representation of the seasons, especially in books aimed at the youngest ‘readers’, such as wimmelbooks. Not only are they crucial for developing emergent and visual literacy, but they also contain normative images that constitute a prototype for the child. The ‘norms’ picturebooks present are based on the authors’ ideologies that constitute all informational picturebooks as their authors interpret facts. Hence, this article aims to analyse the visual strategies used and the ideologies expressed by wimmelbooks from Poland and Germany in representing the seasons (Marcin Strzembosz’s Jaki to miesiąc? [2002] and Ali Mitgutsch’s Mein Wimmel-Bilderbuch: Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter [2007], among others). The preliminary research shows that the authors seem to propose traditional, idyllic, ecologically normative images of the environment, which I propose to call econormative (inspired by the word ‘aetonormative’), such as snowy winters, sunny summers, etc.; hence, wimmelbooks seem to assent to stereotypical depictions of the seasons associated with the notion of ideal childhoods set in econormative environments.

1. Introduction

Despite the growing number of children’s books on environmental topics, climate crisis, and global warming—both in my motherland, Poland, and worldwide—there is still a significant number of books that seem to ignore environmental changes.1 Among them are picturebooks—narrative and nonnarrative, fiction and non-fiction—that combine words and images to present the surrounding world to the young reader. In this article, I focus on selected central European informational picturebooks aimed at very young children (from 0 to 32) wherein the visuals dominate in quantity over words, i.e., wordless or almost-wordless picturebooks, particularly, wimmelbooks. The aim of this article is twofold: to discuss how knowledge is transferred via visual codes in wimmelbooks and investigate how wordless informational picturebooks represent the four seasons.3

I chose this ‘genre’ for discussing the representation of nature and the environmental changes because many titles are both realistic and dedicated to the four seasons, including the world-famous Wimmelbuch [All Around Bustletown] series (2003–2008) by German artist Rotraut Susanne Berner. At the same time, I did not identify any wimmelbooks explicitly dealing with climate change; hence, I decided to focus on titles touching on the seasons. I decided to focus on picturebooks from my motherland, Poland, and another country to verify whether the representation of seasons might be a universal phenomenon. I chose Germany because of its temperate climate and its position as a cornerstone for wimmelbooks, with Ali Mitgutsch as a pioneer of the ‘genre’ (Rémi 2018, p. 158).

Some wimmelbook titles fall under the umbrella category of informational picturebooks, whose authors—as states Nikola von Merveldt—“select, organize, and interpret facts and figures using verbal and visual codes... making information accessible to the interested layperson, engaging readers intellectually and emotionally” (2018, p. 232). In her essay from The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks, von Merveldt lists several formats of ‘informational picturebooks’, including concept books and wimmelbooks, that is, ‘genres’4 aimed at the youngest readers. For my analysis, I selected wimmelbooks, defined by Cornelia Rémi as sets of “doublespreads present[ing] a detailed panoramic landscape which encloses several minor scenes, richly populated by dozens of characters… engaged in simultaneous interactions and often subtly connected to each other” (2018, p. 158). World-known examples of wimmelbooks are Berner’s Wimmelbuch series or the Mamoko [The World of Mamoko] series (2010–2014) by Polish duet Aleksandra and Daniel Mizielińscy (Galling and Wiebe 2022).

The selection process of the particular works was relatively intuitive and not well-structured; that is because in library catalogues, one may not find a keyword in either the German Internationale Jugendbibliothek [International Youth Library] in Munich or Polish Biblioteka Narodowa [National Library] in Warsaw.5 My analysis will cover a Polish edition of Ali Mitgutsch’s Mein Wimmel-Bilderbuch: Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter [My Wimmelbook: Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter] (1968/2007, published in Poland in 2015 as Wiosna, lato, jesień, zima) and the following Polish works: Marcin Strzembosz’s Jaki to miesiąc? [What Month Is It?] (2002), Rok w przedszkolu [A Year in the Kindergarten] by Przemek Liput (2016), Rok w górach [A Year in the Mountains] by Małgosia Piątkowska (2020), and Rok na zamku [A Year in the Castle] by Nikola Kucharska (2021).

The wimmelbooks taken into consideration fall under the umbrella category of informational picturebooks6; hence, they are hybrid in form: their informational aspect, traditionally connected to the lack of narrative, may seem contradictory to their narrative nature, which led Jörg Meibauer (2017, p. 53) to classify wimmelbooks as simple narrative picturebooks and not ‘descriptive’ ones.7 Nevertheless, I will follow von Merveldt’s footsteps and assume some wimmelbooks may be informational. I also argue that they share some characteristics with concept books: they are aimed at the youngest readers, have no or little words, and generally represent basic elements from the real world, i.e., concepts (Kümmerling-Meibauer and Meibauer 2018).

Besides sharing some points in common with concept books—such as being “models of the world” (Rémi 2011, p. 121)—wimmelbooks also fall under the category of wordless or almost-wordless picturebooks. As stressed in many definitions, a picturebook combines verbal and visual levels; the ‘synergy’ of these two modes of communication offers complex (narrative or nonnarrative) content. As picturebooks with no words are also published, Emma Bosch proposed to redefine a picturebook as a “story composed of fixed, printed, sequential images consolidated in a book structure whose unit is the page and in which the illustrations are primordial and the text may be underlying” (Bosch 2018, p. 191). Building on this, she notes that in wordless picturebooks, “apart from the title, the name(s) of the author(s) and the credits, no other words appear in the pages of the book” (p. 191). Almost-wordless picturebooks are then “those narratives conceived essentially as visual representations that include a number of words on their pages. These could be single words, sentences, paragraphs or even some pages of text” (p. 191).

Wimmelbooks may come in different shapes and forms—most often in a big folio format—and are usually wordless or almost-wordless, welcoming readers from various backgrounds as knowledge of a particular language is not necessary, thus making them “internationally accessible” (Galling and Wiebe 2022, p. 85). Nonetheless, the ones that present changing seasons are most often wordless (besides the title and author’s name, there is sometimes a blurb on the back cover), but almost-wordless wimmelbooks are also popular (brief notes on the elements or characters depicted may be found in the book as well as ‘titles’ of the doublespreads). Moreover, from their very nature, wimmelbooks are open to dialogic reading by young children and adult mediators who may point at certain elements, ask about them, name them, and so on. These individual readings are intriguing and worth further investigation. Still, my analysis will focus on verbal and visual strategies used in the selected wimmelbooks in transferring knowledge on the four seasons.

2. Methods: Transferring Information through Visuals

Wimmelbooks are one of the most visually complex wordless picturebooks. On the one hand, with impressive precursors in the history of art, such as Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Rémi 2018, p. 160), wimmelbooks bear high artistic value. They may also be analysed in terms of works of art as one may observe different graphic styles that the authors use (p. 159). As I focus on informational wimmelbooks, their artistic aspect is out of the scope of my study. On the other hand, wimmelbooks often present everyday situations, places, and actions, developing cognitive competencies of a young child reader, including language acquisition and visual literacy; visual literacy includes recognising images, for example, connected to the environment and changes of the seasons. Visual literacy is also stimulated by the abundance of images that children may study in detail, the connection of multiple elements, and the decoding of meanings before “they actually can decode written words” (p. 161). As Cornelia Rémi stresses, wimmelbooks also strongly support cognitive development, including narrative skills that allow them to create simple or more complex stories based on the characters and events they see on the following doublespreads (2011). Moreover, wimmelbooks may be perceived as informational picturebooks, as they often recall the real world and represent everyday situations, objects, actions, or locations that a young child reader can relate to and learn from (2018, p. 163).

Many scholars stress the educational potential of picturebooks: not only the informational ones but also the fictional ones (Kümmerling-Meibauer et al. 2017). Perry Nodelman’s anecdote serves as an example of this common conviction:

My students... think that while words are always hard to understand, the right sort of pictures—ones that are simple and clear and non-abstract—require no effort at all. In fact, they believe that is why children’s books contain pictures; the pictures contain information that allows children to understand the words.(Nodelman 1981, p. 57, emphasis in the original)

Although later in his essay Nodelman explicitly states that “children’s books do not contain pictures merely to convey factual information” (p. 57), it is commonly known that images serve as important elements in informational picturebooks, especially those with little or no words, like wimmelbooks. In such picturebooks, visuals dominate in terms of quantity and serve as a medium for transferring meaning and information. This clearly refers to semiotics as this approach focuses on “codes and context on which the communication of meaning depends”, an important point of departure for some picturebook researchers (Nodelman 1988, p. ix).

In this field, semiotic models of picturebooks were developed, but only recently has such an approach been used to investigate informational picturebooks. In her two complementary essays, Smiljana Narančić Kovač (2020, 2021) proposes an analytical tool for the semiotic analysis of ‘non-fiction’ and ‘nonnarrative’ picturebooks.8 A graph developed from her previously published semiotic model of the narrative picturebook (Narančić Kovač 2018, p. 412; 2021, p. 42) adjusted to these two types of picturebooks consists of “knowledge” instead of “story” (2021).9 Nonnarrative picturebooks—according to Narančić Kovač’s semiotic approach—are based on the coexistence of knowledge (content, understood as the substance of knowledge and form of knowledge) and two discourses: visual and verbal (both built from form and substance).

While investigating wordless informational picturebooks that may fall under these models, I focus mainly on visual discourse (form and substance) and visual content (story or knowledge). Form and substance that are given in the images require visual literacy that enables the reader to understand—and possibly utter10 or narrate—what is being shown in the illustrations: separating individual elements from the background and separating individual elements from each other (elements may be contoured or not), understanding the scaling of the elements, etc. As for the content, it may consist of objects and actions often known to the child reader; hence—as Narančić Kovač puts it—“visual discours[e] possess[es] a potential to offer information referring to different types of worlds” (2020, p. 75), including the real world surrounding the child. Moreover, new elements may also be identified, named, and explained only with the help of an adult mediator.

Wimmelbooks’ hybrid nature of being both narrative and non-narrative makes their analysis in the context of von Merveldt’s definition of an informational picturebook rather complex. That is why referring to the semiotic models of both narrative and nonnarrative picturebooks designed by Narančić Kovač is appealing and fruitful. On the one hand, a single doublespread in a wimmelbook set in a specific time and space shows a nonnarrative composition of elements that relate to each other and together create an image of a particular landscape filled with single elements that build on an image of a specific setting or a scene. On the other hand, the two following doublespreads create a narrative sequence to be told by the reader: the time distance between scenes shown on two consecutive doublespreads may vary from a few minutes (Wimmelbuch series by Berner) to one month (Strzembosz, Liput, Piątkowska, and Kucharska) or even more (Mitgutsch).

3. Analysis

As shown in one of the most famous wimmelbook series by Berner (Galling and Wiebe 2022, p. 84), wimmelbooks often explicitly or implicitly touch upon the seasons11; hence, I will use a theoretical framework to analyse selected wimmelbooks that focus on the four seasons published in Poland in the 21st century. First, I will investigate a Polish translation of Mitgutsch’s Mein Wimmel-Bilderbuch: Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter (1968/2007). Then, I will focus on original Polish works, starting with Strzembosz’s Jaki to miesiąc? (2002). Finally, I will analyse three titles from the series Rok w… [A Year in…] (2015–2021) by Nasza Księgarnia publishing house: Rok w przedszkolu by Liput (2016), Rok w górach by Piątkowska (2020), and Rok na zamku by Kucharska (2021). All the books published originally in Germany and Poland are based in central Europe; hence, they are culturally and geographically specific for this region, and naturally, the outcomes of my study may not be relevant to the other areas: not only northern or southern Europe (sharing the same temperate climate) but also subtropical regions like southeast Asia, where two main tropical seasons—dry and wet—occur. Conversely, I wish for my study to serve as a point of departure for deepened comparative analyses, as some of these books were also translated and published in countries such as the UK and USA (Kucharska 2024) or Spain (Kucharska 2022), resulting in a potentially broad global market of English- and Spanish-speaking countries; hence, further research may trace the translation practices and reception of these picturebooks outside of central Europe. Above all, a comparative study of international picturebooks representing the four, two, or any number of seasons occurring in different parts of the world may be of great importance in times of climate change and developing studies in the field of environmental children’s literature. Hence, the scope of my analysis is narrower and hopefully will serve as the starting point for further research.

Starting from a German example, Mitgutsch’s Mein Wimmel-Bilderbuch (1968/2007) explicitly touches on the four seasons as given in the subtitle Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter. Moreover, the title also indicates the order that the content is presented, starting with spring, on through to summer, then to autumn, and finally winter; hence, the readers already know what they might expect from the book as well as what they might learn of the season’s changes and the number of seasons characteristic for the temperate climate of central Europe. Mitgutsch’s book consists of eight doublespreads (front and back cover illustrations included as one of them), so it may be assumed that each of the four seasons is shown in two illustrations. The title indicates that the cover and the first doublespread are spring, doublespreads 2 and 3 are summer, doublespreads 4 and 5 are autumn, and doublespreads 6 and 7 are winter. What is important is that all the scenes are set in a park, a place in nature filled with trees, a small lake, and a river inhabited by animals and visited by people; as Rémi (2018, p. 163) notes, this “fictional setting” gives us impressions of Englischer Garten, an actual park in the city centre of Munich, Germany. Moreover, all the doublespreads depict the same park, but the scenery is ‘moving’ from one point to the other (from left to right). As Ines Galling and Katja Wiebe pointed out, “movement of time and space and motion of the different characters are central in narrative wimmelbooks such as Rotraut Susanne Berner’s stories” (2022, p. 84). This notion may also be applied to Mitgutsch’s Mein Wimmel-Bilderbuch.

During spring, the figures depicted wear long sleeves and long trousers; some eat ice creams, and some play in the water; hence, the temperature seems moderate. The dominant colour is bright green, but many colourful details also appear, such as pink flowers blossoming on—probably cherry—trees. Also, some characters make floral wreaths, and nature seems to be coming back to life. In the summer, flowers disappear, and green dominates again, but it is more unified, as grass and tree crowns are intensively green. The people are very often half-naked, wearing shorts and bath suits, or even fully naked: one male character sitting on the riverbank is drying himself while presenting the front of his body with a visible penis12. The temperatures are probably very high based on the limited clothing, both in the first doublespread presenting daytime and the second depicting nighttime. The weather—understood as the state of the atmosphere, describing, for example, the temperature, humidity, and wind strength—also seems to be constant, as, in both scenes, the characters are engaged in leisure activities. The first autumn doublespread mixes green with yellow as some tree crowns slowly change their colours. The people wear long sleeves and long trousers like in the spring doublespreads, and among other activities, they collect apples (in Central Europe, these fruits are collected in autumn) and fly kites or other flying toys; hence, the wind is relatively strong. This notion of stress in the second autumn doublespread explains that it is so windy that the people can barely stand still, and the colour palette is grey, but now, it indicates stormy weather during the daytime, not nighttime as in the second summer doublespread. According to the images in Mitgutsch’s wimmelbook, autumn is then an unstable season with both weather enabling leisure in the park and that which is more dynamic, even dangerous nature, as there are a few broken trees and people chasing their umbrellas as they are flying away. The last two winter doublespreads are set in a white palette as snow covers the park, with many colourful details like human figures wearing warmer clothes and playing with the snow or ice-skating. The natural world is represented by brownish and blackish trees with no leaves, embraced by the piles of hay and a frozen lake. When the last page is turned, the reader encounters the back cover that is partially the very first spring doublespread; hence, the reading becomes a circular, recurring experience, just as the seasons are. This aspect of wimmelbooks is also stressed by Rémi, who argues that “narrative wimmelbooks reward multiple rereadings” (2018, p. 164). As Mitgutsch’s Mein Wimmel-Bilderbuch: Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter proves, this may also be applied to non-narrative (or at least less evidently narrative) wimmelbooks. For my study, what is also crucial is the Polish peritext that stresses the informational nature of the book: “Zobaczcie, jak zmienia się świat!” [See how the world changes!]13 (Mitgutsch 2015, back cover). The German edition lacks a similar sentence; hence, peritextual features are constructed by the publisher and may vary depending on the particular language edition, providing (or not providing) the reader with suggestions on how to read the wimmelbook.

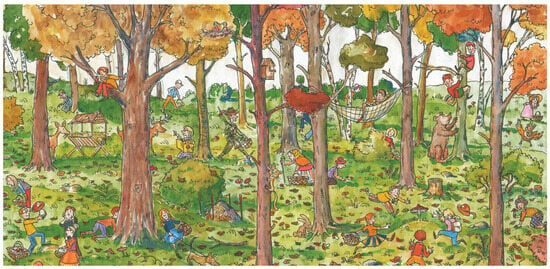

The way Mitgutsch depicted the four seasons also reappears in a specific type of wimmelbooks on the seasons which instead focus on presenting the twelve months of the year and that may be found in the Polish children’s book market. The first example is Jaki to miesiąc? by Strzembosz, quite a unique wimmelbook because of its small format (21 × 21 cm). Nevertheless, the author created twelve wimmelpictures dense with elements depicting the twelve months, one for each doublespread, starting from January and ending with December. Different from Mitgutsch’s wimmelbook, the front and back covers of Jaki to miesiąc? copy one of the doublespreads depicting May. Each doublespread presents a different setting, including an ice ring in the city centre (January), a river in the countryside (March), a zoo (June), or a classroom (September). Additionally, on each doublespread, the Polish name of each month was incorporated into the image, but these names are not easy to spot at first glance; for instance, “Październik” [October] is carved on a trunk of the third tree from the left (Figure 1). The images recall how Mitgutsch depicted the seasons: so, there is snow in January, February, and December; green grass dominates in March, April, and May; the beach is a July setting; and yellow and brown leaves are part of the forest image in October (Figure 1). What makes it a cognitively challenging book is how Strzembosz connects particular months with traditional holidays or customs and important events in children’s lives in Poland, such as the beginning of a school year in September, throwing an effigy of Marzanna into the river to end the winter in March, and Christmas in December. Here, the peritext is also of great importance, as it stresses the informational character of the book: “Poznaj 12 miesięcy. Zobacz, jak zmieniają się pory roku” [Learn about the 12 months. See how the seasons change] (Strzembosz 2002, back cover). Surprisingly, the names of the four seasons do not appear in the book, nor is the moment when one changes into the next shown; hence, it is up to the readers to decide which doublespreads present winter, spring, summer, and autumn. Therefore, the temporality in Strzembosz’s wimmelbook does not depend on natural changes but is strictly associated with the Gregorian calendar presenting the seasons mentioned in the peritext.

Figure 1.

October from Marcin Strzembosz’s Jaki to miesiąc? [What Month Is It?] (2002). Image courtesy of the publisher.

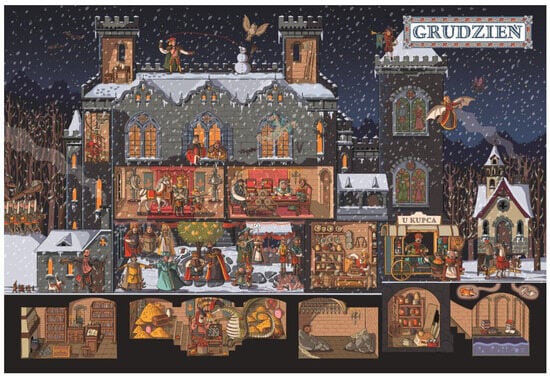

The tendency to coin the seasons changes with the changing months in a similar way is more explicit in books from the Rok w… series by Nasza Księgarnia publishing house, showing in each title a particular place like a city, a forest, a market, a countryside, a construction site, etc. Each book’s front cover combines four fragments of selected doublespreads and covers all four seasons; then, there is an opening doublespread presenting characters from the book with short captions, and then, the same setting is shown in the twelve months of the year beginning with January and ending with December. Despite the traditional depiction of the seasons as shown in Mitgutsch’s and Strzembosz’s wimmelbooks, some settings influence their seasonal images, for example, in Rok w górach by Piątkowska (2020), the snow stays longer (January, February, March, April, November, and December) than in other books in the series as the wimmelbook is set in the high mountains. Also, the peritext in the back cover stresses the biological diversity of the mountains the reader will acquire. As for traditional depictions of the four seasons, they are also present in more fantastical than realistic picturebooks, including Rok na zamku by Kucharska (2021)14. Despite some fantastical elements (a witch, a dragon), the wimmelbook, set in historically inaccurate medieval times, also addresses not only the temporality of the changing months and the seasons but also the relationship between synchrony and diachrony. On the one hand, it fits other titles in the series that show contemporary times; on the other, it stresses the longitude of the four seasons we know (winter, spring, summer, and autumn were the same some ages ago, even if the wimmelbook is not historically accurate), hence sustaining the normative representation of the four seasons, like the snowy winter of December with leafless trees and a snowman (Figure 2). The peritext on the back cover goes, “w każdym miesiącu uważni obserwatorzy będą mogli śledzić wiele niezwykłych wydarzeń, zmiany pogody, pór roku i dnia” [each month, attentive observers will be able to follow many unusual events, changes in weather, seasons and days] (Kucharska 2021, back cover)15; hence, it does not focus on the seasons but lists them as one of the possible reading strategies. It is also important to note that most books published in the Rok w… series depict the outdoors, such as a city, a forest16, a countryside, a market, a construction site, and the mountains. Only two of these books focus on the indoors: Rok w przedszkolu by Przemek Liput (2016) and Rok na zamku by Kucharska (2021); nevertheless, in these books, nature is clearly visible: the changing seasons influence not only the environment seen through the windows or the scenes set in the playground in Rok w przedszkolu (despite the seasons not being mentioned in the peritext on the back cover) or thanks to the use of cross-sections in Rok na zamku but also influence the characters and the way they dress and act.

Figure 2.

December from Nikola Kucharska’s Rok na zamku [A Year in the Castle] (2021). Image courtesy of the publisher.

4. Results: Econormativity in Wimmelbooks on the Four Seasons

Stereotypical and normative are the words that may be used to describe the representation of the four seasons in the central European wimmelbooks analysed. As Michael Kammen (2004, p. 1) notes, “images evoked by the seasons long ago achieved certain conventional forms so that a visual vocabulary became familiar to most members of society”; an example coming from the history of art may be a series of paintings De twaalf maanden [Months of the Year] by Dutch painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder, also known as a precursor of the wimmelpictures later created by the wimmelbook authors (Rémi 2018, p. 158). Visual representations of the four seasons in the wimmelbooks analysed are associated with their environmental factors, i.e., weather changes, ecology (plant and animal activity, including bear hibernation and the flowering of plants), and intensity of sunlight (Macauley 2018, pp. 3–4); above all, David Macauley stresses the “centrality of weather” (p. 5).

The weather seems to be the most important notion of the four seasons changes in the wimmelbooks analysed. As the titles refer directly to the seasons, I draw attention more to climate change and less to the weather, the latter of which changes constantly and may be different in different locations. One may wonder whether the images created by Mitgutsch, Strzembosz, Liput, Piątkowska, and Kucharska reflect the actual climate dominating in their times. Still, as these books touch on universal topics such as the everyday life of characters in more (Mitgutsch, Strzembosz, Liput, Piątkowska) or less (Kucharska) realistic settings, their actual years of publication seem less relevant. Moreover, the images seem idyllic (cf. Rinnerthaler 2020, p. 242) and are strongly connected to nature and less anthropocentric and, as such, point directly to childhood, often associated with idyl and nature (Rättyä 2018, p. 170). This is also reflected in language with phrases such as “idyllic childhood”. Hence, I believe stereotypical environmental representations in the analysed wimmelbooks sustain both ecological and social norms of behaviour during the different seasons. If one agrees with Rémi, it is rather understandable that wimmelbooks should serve as a source of generic images and as models of the world for very young readers (2011, p. 121). The analysed picturebooks present what is considered a prototype of the four seasons in Germany and Poland and may be described as econormative. I borrow this term from queer and environmental studies (‘eco-normativity’ in (Di Chiro 2010); ‘econormativity’ in (Tirapani and Willmott 2023)) to introduce it in the field of children’s literature. Contrary to previous scholars who applied the term in the field of social sciences and philosophy, I propose a definition inspired by Maria Nikolajeva’s aetonormativity, that is, “adult normativity that governs the way children’s literature has been patterned from its emergence until the present day” (Nikolajeva 2010, p. 8). I propose using the term econormativity to characterise works that reproduce traditional images of nature, the environment, and the climate, simply because climate change would not be happening in these images. In that manner, in central European picturebooks, the econormative features are snowy winters and sunny summers with no trace of rapid climate change occurring in the last decades. I believe the notion of econormativity might be used in terms of wimmelbooks, picturebooks, and children’s literature in general as it often reproduces idyllic representations of the environment.

In the face of a growing number of environmentally conscious picturebooks dealing with climate change, one may wonder how to approach econormative works such as the titles analysed above. Naturally, ecocriticism seems to be both a suitable and evident approach to representations of nature in picturebooks (Goga and Pujol-Valls 2020; Campagnaro and Goga 2021; Rättyä 2018); one may wonder why there are no explicit images that would draw readers’ attention to climate change, such as the school strikes represented in one of the images. Conversely, I propose to read econormative wimmelbooks with the help of studies on ideology in children’s literature. Indeed, different ideologies constitute all ‘subgenres’ of informational picturebooks (including wimmelbooks), as their authors “select, organize, and interpret facts and figures” (von Merveldt 2018, p. 232). Authors promote certain views and interpretations of the surrounding reality through their books as some studies on ideology in informational picturebooks have shown (Panaou and Yannicopoulou 2021; Dymel-Trzebiatowska 2021). Still, more studies in this field are needed, especially in the time of swiftly spreading fake news. As for analytical tools, I find Robert D. Sutherland’s definition of ideology and the typology of politics used to introduce it very helpful. In his 1985 article, he states, “like other types of literature, works written especially for children are informed and shaped by the authors’ respective value system, their notions of how the world is or ought to be. These values… constitute authors’ ideologies” (Sutherland 1985, p. 143, italics in original). Sutherland also proposes a classification of three types of ideological expressions: ‘the politics of advocacy’ that advocate for a specific cause, ‘the politics of attack’ that attacks it, and ‘the politics of assent’. The last one

[s]imply affirms ideologies generally prevalent in the society... “assent” is an author’s passive, unquestioning acceptance and internalization of an established ideology, which is then transmitted in the author’s writing in an unconscious manner. The ideology subscribed to is a set of values and beliefs widely held in the society at large which reflects the society’s assumptions about what the world is... Most readers (sharing this ideology with the author) will not recognize its presence in the work, for the work will reflect back their own assumptions about what the world is and simply reinforce them in their beliefs. Nor is the author consciously aware of the ideology informing the work. Since neither author nor readers can conceive the world as being otherwise than what the ideology claims, the ideology—when expressed in a published literary work—is persuasive because it tends to support and reinforce the status quo”.(pp. 151–52, italics in original)

It seems that central European wimmelbooks on the four seasons support and reinforce the status quo in the representation of seasons, as they present econormative images of the seasonal changes occurring on the planet. On the one hand, they seem to do it in line with the book’s main topic, as peritexts of Mitgutsch’s and Strzembosz’s wimmelbooks explicitly indicate that the reader will learn about the seasons in the first place. On the other, despite the temporality of the changing months and the season stressed by the title of the book or a series, learning about the seasons is weakened by the peritext (Piątkowska 2020; Kucharska 2021) or absent (Liput 2016). Either way, this may lead to a discrepancy between what young readers learn about the four seasons and the climate change they will learn about later in life or the phenomena they already notice.

5. Conclusions

This preliminary research shows that authors seem to propose the traditional, idyllic, ecologically normative images of the environment I propose to call econormative; hence, wimmelbooks seem to assent stereotypical depictions of the four seasons associated with the notion of ideal econormative childhoods. Such representation in the face of a growing number of environmental picturebooks may be challenging for both readers and teachers or librarians who may wish to use such works for many of their cognitive qualities but who are yet unsure about the content such books may present. A possible solution may be critical reading in line with Sutherland’s analysis of ideology and politics in children’s literature that opens young and adult readers to a form of dialogue, preferably a green dialogue (Goga and Pujol-Valls 2020; Campagnaro and Goga 2021), focussing on their approach towards environmental issues.

Funding

The author wrote this article as part of the research project “Dziecięca książka informacyjna w XXI wieku: tendencje–metody badań–modele lektury” [Informational children’s books in the 21st century: trends–research methods–models of reading]. This project received funding from the National Science Centre (Poland) under the Preludium grant programme (grant agreement no. 2020/37/N/HS2/00312).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This article was published free of the Article Processing Charge (APC). I want to thank the participants of the Grow Workshop for Early Scholars in European Children’s Literature Research (23–25 November 2022) for their valuable feedback, especially Rosalyn Borst, Nina Goga, Anne Klomberg, Chiara Malpezzi, and Smiljana Narančić Kovač. Also, I am grateful to the members of the Laboratory of Semiotics at the Faculty of “Artes Liberales” of the University of Warsaw for their comments on the initial version of the manuscript. Moreover, I thank the three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful notes. |

| 2 | This age category comes from the subtitle of the book Emergent Literacy: Children’s Books from 0 to 3 edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer (2011). Rémi’s essay on wimmelbooks was included in this volume; hence, I assume they are aimed at very young readers, although she does state that “these books accompany children from their first year of life to elementary school and beyond” (2011, p. 115) and “are a threshold or bridge genre, varied enough to accompany children through many stages of their path to literacy” (p. 116; cf. 2018, p. 159). |

| 3 | In this article, I focus on wimmelbooks, but it is worth noting there are also other wordless and almost-wordless picturebooks that share knowledge about the four seasons, such as Avant après by Anne-Margot Ramstein and Matthias Arégui (2013) or En 4 temps by Bernadette Gervais (2020). |

| 4 | I use the term “genre” which von Merveldt uses along with “form”, but each informational picturebook is rather a hybrid of verbal and visual genres and forms (2018, pp. 233–34). |

| 5 | In the Internationale Jugendbibliothek [International Youth Library] in Munich catalogue, the keywords used to tag books by Migutsch or Berner are, for instance, “Suchbild” [search-image] and “Bilderbuch” [picturebook]; in the Biblioteka Narodowa [National Library] in Warsaw, Mamoko books by Mizielińscy are tagged with “książka zabawka” [toy book] and “książka obrazkowa” [picturebook]. |

| 6 | Not all wimmelbooks are informational as some of them present unrealistic (e.g., Mizielińscy’s Mamoko series) or even fantastical and surrealistic settings (Peter Goes’s Feest voor Finn: Een zoek- en vindboek [Follow Finn: A Search-and-Find Maze Book, 2017], for instance), but still, they may be used as tools to develop narrative or language skills; hence, their educational nature is inevitable (Rybak et al. 2022, pp. 366–67). |

| 7 | Meibauer uses the term “descriptive” instead of the more popular ‘non-fiction’ or ‘informational’ (2017, p. 52). |

| 8 | In one of the articles, Narančić Kovač uses the term “non-fiction picturebooks” (2020), and in the other, she uses “nonnarrative picturebooks” (2021). In the former, she elaborates on the nature of non-fiction picturebooks, stating that these books may be both narrative and non-narrative. |

| 9 | Narančić Kovač’s semiotic models of the narrative picturebook and nonnarrative picturebook may be found in Verbal and Visual Strategies in Nonfiction Picturebooks, available as open access material here: https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215042459-2021. |

| 10 | I use Narančić Kovač’s term “utterer” referring to the voice in nonnarrative texts as an analogy to the ‘narrator’ (2021, p. 44). |

| 11 | The original German titles of the Wimmelbuch series books (2003–2008) are Winter-Wimmelbuch [Winter-Wimmelbook] (2003), Frühlings-Wimmelbuch [Spring-Wimmelbook] (2004), Sommer-Wimmelbuch [Summer-Wimmelbook] (2005), Herbst-Wimmelbuch [Autumn-Wimmelbook] (2005), and Nacht-Wimmelbuch [Night-Wimmelbook] (2008). Their titles are translated rather literally in other languages, for example, Winter-Wimmelbuch is All Around Bustletown: Winter in English, El libro del invierno [The Book of Winter] in Spanish, Le Livre de l’hiver [The Book of Winter] in French, Wat een winter. Kijk- en zoekboek [What a Winter: A Look-and-Find Searchbook] in Dutch, and Stora vinterboken [The Great Winter Book] in Swedish. |

| 12 | Such explicit nudity might be controversial to some adults, in a particular case known as “Wimmel-Pimmel-Skandal” [Wimmel-willy-scandal]; in 2007, an American publisher asked Rotraut Susane Berner to retouch an image of a statue in an art museum with a visible penis in her book Winter-Wimmelbuch. She refused, and eventually, the book was not published (Rinnerthaler 2020, pp. 241–42). |

| 13 | If the translator is not indicated in the references, the translations are mine. |

| 14 | The English subtitle of Kucharska’s (2024) A Year in the Castle is A Look and Find Fantasy Story Book and stresses the unrealistic nature of the content. |

| 15 | The English peritexts goes: “Vibrant and intricately detailed spreads take readers through a year in the castle, showing how an innocent mishap leads to war with the neighbors; how lives in the castle change from month to month; and how each season brings its own surprises” (Kucharska 2024, back cover). |

| 16 | Emilia Dziubak (2015)—author of Rok w lesie [A Year in the Forest]—presents this title as an educational book that required deepened research and weeks of preparations before she actually started her work (Gawryluk et al. 2021, p. 166). |

References

- Bosch, Emma. 2018. Wordless Picturebooks. In The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer. New York: Routledge, pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnaro, Marnie, and Nina Goga. 2021. Green Dialogues and Digital Collaboration on Nonfiction Children’s Literature. Journal of Literary Education 4: 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Chiro, Giovanna. 2010. Polluted Politics? Confronting Toxic Discourses, Sex Panis, and Eco-Normativity. In Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire. Edited by Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 199–230. [Google Scholar]

- Dymel-Trzebiatowska, Hanna. 2021. Transgressing cultural borders. Controversial Swedish nonfiction picturebooks in Polish translations. In Verbal and Visual Strategies in Nonfiction Picturebooks: Theoretical and Analytical Approaches. Edited by Nina Goga, Sarah Hoem Iversen and Anne-Stefi Teigland. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, pp. 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, Emilia. 2015. Rok w lesie. Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia. [Google Scholar]

- Galling, Ines, and Katja Wiebe. 2022. The Whole World on One Page—Wimmelbooks: An International Perspective. Bookbird 4: 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawryluk, Barbara, Katarzyna Lajborek, and Magdalena Korobkiewicz. 2021. Sto lat wydawnictwa Nasza Księgarnia. Znamy się od dziecka. Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais, Bernadette. 2020. En 4 temps. Paris: Albin Michel Jeunesse. [Google Scholar]

- Goga, Nina, and Maria Pujol-Valls. 2020. Ecocritical Engagement with Picturebook through Literature Conversations about Beatrice Alemagne’s On a Magical Do-Nothing Day. Sustainability 12: 7653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammen, Michael. 2004. A Time to Every Purpose: The Four Seasons in American Culture. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska, Nikola. 2021. Rok na zamku. Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska, Nikola. 2022. Un año en el castillo. Translated by Patrycja Jurkowska. Madrid: SM. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska, Nikola. 2024. A Year in the Castle: A Look and Find Fantasy Story Book. Translated by Anna Władyka-Leittretter. London and New York: Prestel Junior. [Google Scholar]

- Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina. 2011. Emerging Literacy and Children’s Literature. In Emergent Literacy: Children’s Books from 0 to 3. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina, and Jörg Meibauer. 2018. Early-Concept Books and Concept Books. In The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer. New York: Routledge, pp. 149–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina, Jörg Meibauer, Kerstin Nachtigäller, and Katharina J. Rohlfing. 2017. Understanding Learning from Picturebooks: An Introduction. In Learning from Picturebooks: Perspectives from Child Development and Literacy Studies. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Jörg Meibauer, Kerstin Nachtigäller and Katharina J. Rohlfing. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liput, Przemek. 2016. Rok w przedszkolu. Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia. [Google Scholar]

- Macauley, David. 2018. The Four Seasons and the Rhythms of Place-based Time. Environment, Space, Place 10: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meibauer, Jörg. 2017. What the child can learn from simple descriptive picturebooks: An inquiry into Lastwagen/Trucks by Paul Stickland. In Learning from Picturebooks: Perspectives from Child Development and Literacy Studies. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Jörg Meibauer, Kerstin Nachtigäller and Katharina J. Rohlfing. New York: Routledge, pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitgutsch, Ali. 2015. Wiosna, lato, jesień, zima. Warszawa: Tatarak. [Google Scholar]

- Narančić Kovač, Smiljana. 2018. Picturebooks and Narratology. In The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer. New York: Routledge, pp. 409–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narančić Kovač, Smiljana. 2020. A Semiotic Approach to Non-Fiction Picturebooks. In Non-Fiction Picturebooks: Sharing Knowledge as an Aesthetic Experience. Edited by Giorgia Grilli. Pisa: Edizioni ETS, pp. 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Narančić Kovač, Smiljana. 2021. A Semiotic Model of the Nonnarrative Picturebook. In Verbal and Visual Strategies in Nonfiction Picturebooks: Theoretical and Analytical Approaches. Edited by Nina Goga, Sarah Hoem Iversen and Anne-Stefi Teigland. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolajeva, Maria. 2010. Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodelman, Perry. 1981. How Picture Books Work. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 1: 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodelman, Perry. 1988. Words About Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. Athens: The University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Panaou, Petros, and Angela Yannicopoulou. 2021. Ideology in nonfiction picturebooks: Verbal and visual strategies in books about sculptures. In Verbal and Visual Strategies in Nonfiction Picturebooks: Theoretical and Analytical Approaches. Edited by Nina Goga, Sarah Hoem Iversen and Anne-Stefi Teigland. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, pp. 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piątkowska, Małgosia. 2020. Rok w górach. Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia. [Google Scholar]

- Ramstein, Anne-Margot, and Matthias Arégui. 2013. Avant après. Paris: Albin Michel Jeunesse. [Google Scholar]

- Rättyä, Kaisu. 2018. Ecological Settings in Text and Pictures. In Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues. Edited by Nina Goga, Lykke Guanio-Uluru, Bjørg Oddrun Hallås and Aslaug Nyrnes. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 159–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rémi, Cornelia. 2011. Reading as Playing: The Cognitive Challenge of the Wimmelbook. In Emergent Literacy: Children’s Books from 0 to 3. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Press, pp. 115–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rémi, Cornelia. 2018. Wimmelbooks. In The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer. New York: Routledge, pp. 158–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinnerthaler, Peter. 2020. U-/Dys-/Heterotopie? Repräsentationen von Gesellschaft im Wimmelbild(erbuch). In Parole(n)—Politische Dimensionen von Kinder- und Jugendmedien. Edited by Caroline Roeder. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 241–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, Krzysztof, Aleksandra Suchańska, Minerwa Wdzięczkowska, Anna Leszczyńska, Gabriela Niemczynowicz-Szkopek, and Dorota Kowalik. 2022. Dziecięca książka informacyjna w Polsce. Wybrane problemy. Filoteknos 12: 363–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzembosz, Marcin. 2002. Jaki to Miesiąc? Warszawa: Muchomor. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, Robert D. 1985. Hidden Persuaders: Political Ideologies in Literature for Children. Children’s Literature in Education 16: 143–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirapani, Alessandro Niccolò, and Hugh Willmott. 2023. Revisiting Conflict: Neoliberalism as Work in the Gig Economy. Human Relations 76: 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Merveldt, Nikola. 2018. Informational Picturebooks. In The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks. Edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer. New York: Routledge, pp. 231–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).