1. Introduction

Side-channel attacks have evolved from traditional cache-timing exploits to a broader class of microarchitectural channels that exploit shared system resources such as page tables, Translation Lookaside Buffers (TLBs), and Performance Monitoring Units (PMUs). These hardware components, while designed for performance optimization, can inadvertently expose timing and other public state-based variations that correlate well with private program states. Consequently, even unprivileged user-space processes can sometimes infer cryptographic keys, memory-access patterns, or control-flow paths from indirect hardware measurements.

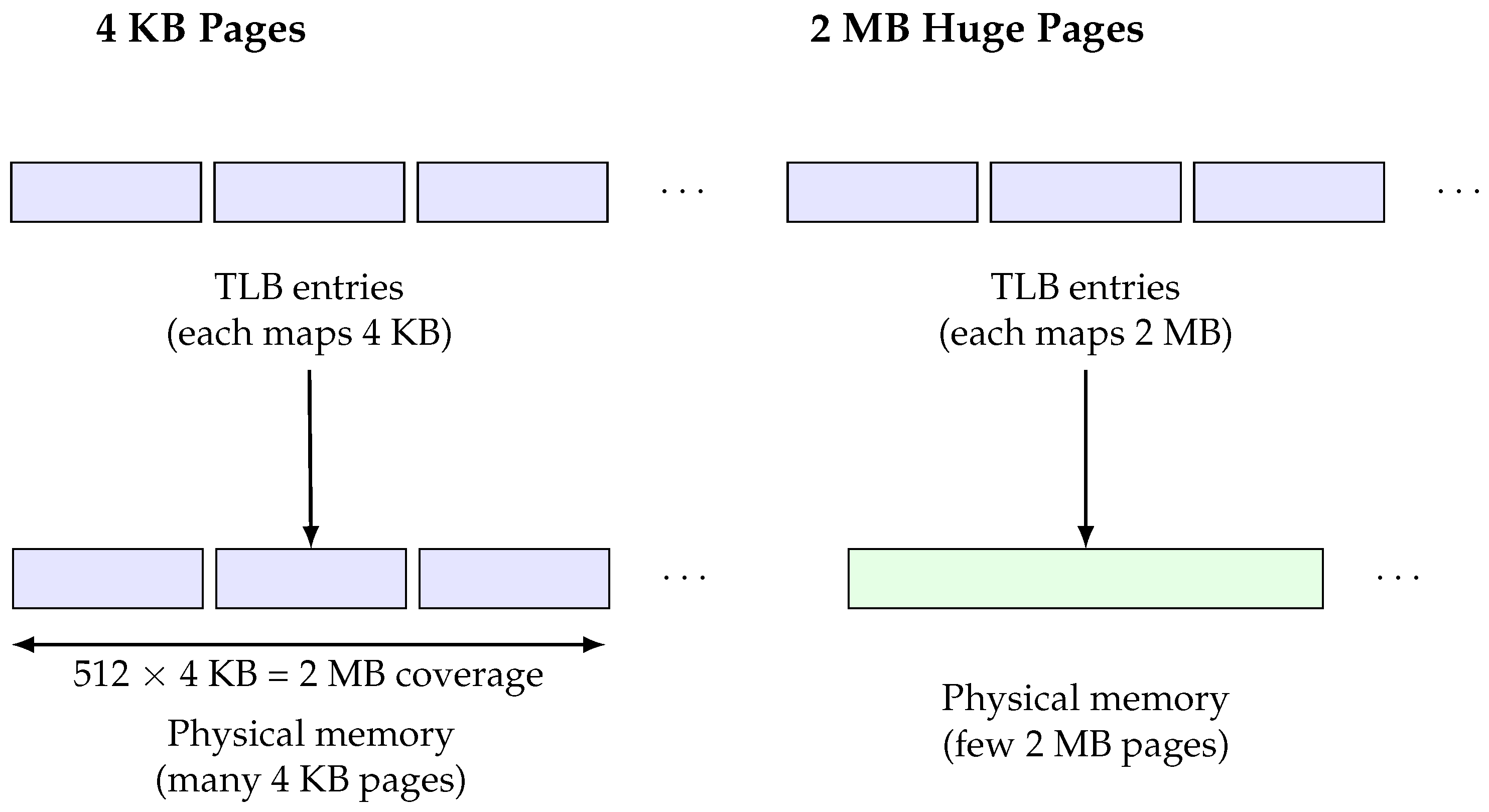

While extensive research has analyzed cache-based side channels and speculative (transient)-execution vulnerabilities, the impact of memory page granularity on application performance and security—specifically the distinction between standard 4 KB pages and 2 MB hugepages—remains relatively underexplored. Page size fundamentally shapes how virtual addresses are translated into physical memory: 4 KB pages produce frequent TLB lookups and fine-grained page-table entries, whereas 2 MB hugepages consolidate 512 contiguous 4 KB regions into a single TLB entry, significantly reducing translation overhead and improving spatial locality [

1]. These architectural differences can affect both (1) the amount of information leaked through memory translation events and (2) the overall runtime performance of memory-intensive workloads.

In particular, page-level leakage—the ability of an attacker to infer which page or memory region the victim accessed—represents an important but under-examined threat model [

2]. TLB collisions can form leakage paths similar to cache side-channels with larger granularity revealing an in-fix of collision address. Previous studies [

2,

3,

4] have shown that page faults and TLB misses can reveal control-flow boundaries or secret-dependent memory regions, but it is unclear how the adoption of large pages alters this leakage surface. On one hand, hugepages may reduce fine-grained address observability of a cache because a single translation covers a broader address range; on the other hand, they may strengthen and aggregate microarchitectural correlations consolidated through pages, exposed by PMU counters.

Although, we do highlight side-channel leakage from cryptographic algorithms, the bias in this paper is to see if cryptographic algorithms consuming large blocks of data can benefit from large pages. TLB side-channel, similar to cache side-channel, is built by attacker program accessing addresses that at page table entry (PTE) level alias or collide with the PTEs of the victim program. By priming the TLB with specific PTEs through a managed address sequence walk, the victim generated addresses can be leaked to an attacker as follows. If the victim accesses a page aliased with an attacker page, the corresponding attacker PTE is displaced from the TLB. Attacker can infer this by re-accessing the priming address sequence and measuring its access time. For a displaced PTE, page table access adds significant time allowing it to be clearly distinguished from a PTE not displaced by the victim. Intuitively, larger pages at least through the TLB entries based collision may yield fewer opportunities for TLB PTE collision, potentially reducing the side-channel leakage. We, however, do not have a comprehensive model of all side-channels that exist and the ones that may be found in the future. The viewpoint we take is that side-channel sensors that are most frequently deployed are performance monitors (PMU) or cache side channels. A broad exploration for what kind of leakage differences exist between 4 KB and 2 MB page based cryptographic computations informs our choice of page size, specifically with respect to performance gains vs leakage trade-off. Once again, the focus is not on finding side-channel leakage of cryptographic computations, but the relative leakage between normal 4 KB and large 2 MB page sizes.

The execution time of a cryptographic algorithm may improve with hugepages if spatial locality exceeding 4 KB exists in the application. Spatial locality may lead to improved time performance for hugepage transfers on a page-fault. The hit rate of the TLB may also improve due to fewer TLB page table entries needed for the same working set.

This research gap motivates our central question:

Do large (2 MB) pages amplify or mitigate side-channel leakage, particularly at the page-number granularity, and can they improve performance without degrading security?

To answer this question, we design a controlled attacker–victim framework that accommodates both configurations. The victim and attacker share a 2 MB memory region that can be backed either by 512 independent 4 KB pages or by a single 2 MB hugepage. This design ensures that both setups operate over identical virtual address ranges and memory access sequences, allowing a fair comparison of leakage strength and runtime behavior. The goal is to classify the secret key of a cryptographic algorithm along some attributes as a leakage metric. Each experiment iterates across 512 4 KB offsets with 25 repetitions per key, producing 12,800 PMU-based readings per cryptographic workload.

Our evaluation spans eight cryptographic modes—AES (GCM, ECB, CBC), ChaCha20, RSA (2048, RAW-256), and ECC (P-256, ECIES-256)—representing both block and stream ciphers as well as asymmetric primitives. Using attacker-side PMU tracing of eight hardware performance counters, we analyze both (i) key-dependent leakage, where classifiers attempt to infer the victim’s cryptographic key class, and (ii) page-number leakage, where classifiers attempt to identify the accessed 4 KB or 2 MB page.

The results indicate that the 2 MB hugepage configuration achieves key-classification accuracy comparable to the 4 KB baseline, showing no increase in side-channel vulnerability. Moreover, page-number identification accuracy remained near random-chance levels (3.6–3.7%), indicating that page-level information was not reliably recoverable through the PMU event set used. At the same time, the hugepage configuration delivers an average 11% runtime performance gain as measured by CPU-cycle counters, reflecting reduced TLB misses and lower page-walk overhead.

These findings provide an important insight: adopting hugepages can enhance performance without amplifying observable side-channel leakage. From both a security and system-design standpoint, our study suggests that memory management configurations—often treated as purely performance optimizations—can play a nuanced but stabilizing role in balancing efficiency and side-channel resilience.

2. Related Work

Side-channel attacks exploiting microarchitectural behaviors have been widely studied in both cryptographic and machine learning contexts. Early attacks such as Prime+Probe and Flush+Reload [

5] targeted shared cache states to leak sensitive operations. More recent work extends these ideas to TLB-based attacks [

2], page-fault side channels [

6], and speculative execution [

7,

8].

PMU-based side channels have also gained traction as they provide fine-grained visibility into architectural events without requiring privileged access [

9]. Tools like

perf and custom instrumentation allow attackers to measure metrics like load/store uops, cache misses, and cycles per instruction, which can correlate with victim computation state [

10,

11,

12].

Page size differences, specifically the use of hugepages, have been studied in the context of performance optimization [

10] and TLB pressure [

4], but their impact on leakage amplification is relatively underexplored. A few research efforts like HugeLeak [

13] have hinted at the potential for hugepages to magnify signal strength by reducing TLB noise and improving spatial correlation.

In the ML domain, side-channel risks have been explored in weight and input recovery [

14], architectural fingerprinting [

15], and membership inference [

16]. Our work contributes to this growing literature by showing that 2 MB hugepages can maintain leakage fidelity while improving runtime efficiency, filling a gap in cross-page-size side-channel evaluations.

3. Background

3.1. Side-Channel Attacks

Side-channel attacks exploit unintended microarchitectural leakage—such as timing variations, cache behavior, or memory access patterns—to infer sensitive program state without directly reading secret data. Classical cache-based attacks such as Flush+Reload and Prime+Probe [

5,

6] have demonstrated that shared cache sets can expose fine-grained victim access patterns. More recent work expands the attack surface to branch predictors, speculative execution [

7], row buffer locality, and TLB behavior [

2]. These attacks remain effective even when cryptographic algorithms are mathematically secure and written in constant-time form.

3.2. PMU-Based Side Channels

Performance Monitoring Units (PMUs) expose hardware event counters including load/store uops, cache misses, branch mispredicts, and TLB refills. While intended for profiling, PMU events correlate with execution behavior and can leak control-flow or secret-dependent operations. Prior work shows that PMU-based leakage can extract AES keys, RSA exponent usage, ECC ladder behavior, or even ML model output class distributions [

9,

15,

17,

18]. PMU attacks are particularly practical in cloud and container environments. PMU-based side-channel attacks—especially those using the perf subsystem—do not require shared memory or precise timing mechanisms (e.g., rdtsc). In many configurations, they can be performed without root privileges and without relying on tightly coupled hardware resources between an attacker and the victim, making them feasible even in constrained or sandboxed environments.

3.3. Huge Pages

Huge pages increase virtual memory page size (e.g., from 4 KB to 2 MB), reducing the number of required page table entries and decreasing TLB pressure. They are widely used in HPC, GPU workloads, and ML frameworks for improved throughput [

19,

20]. However, their impact on side-channel leakage is nuanced: reducing TLB churn may reduce noise, thereby reducing variance in PMU trace signatures [

21]. Whether this stability improves or weakens security depends on the workload and threat model—motivating our empirical study.

3.4. Translation Lookaside Buffers (TLBs)

The TLB caches virtual-to-physical address translations. With 4 KB pages, large memory regions require many entries, making TLB misses frequent and observable via PMU events. With 2 MB pages, the same memory footprint requires far fewer entries [

20]. This reduces page walks and improves runtime efficiency, but it also changes microarchitectural observability. If repeated accesses fall within the same hugepage region, leakage patterns may become more traceable since attacker can create collisions with a victim page more easily. On the flip side though a hugepage’s observable activity is more clustered reducing the attributability to a more specific code segment, making it difficult to draw fine granularity correlations.

3.5. Cryptographic Workloads

Cryptographic kernels such as AES, RSA, and ECC exhibit repeated table lookups, modular arithmetic, or structured memory fetch patterns tied to key material. Even constant-time implementations can exhibit identifiable PMU signatures [

18]. Repeated execution enables classification of key-dependent features. Our evaluation tests eight cryptographic workloads to isolate how page size affects computation state leakage.

Specifically, the selected algorithms expose complementary leakage surfaces: AES modes exhibit structured memory accesses and repeated round-based computation; ChaCha20 emphasizes arithmetic intensity with relatively regular memory behavior; and RSA and ECC introduce complex control flow and large-integer arithmetic [

22,

23,

24]. Together, these workloads span symmetric and asymmetric cryptography and cover a wide range of memory–compute trade-offs, making them representative of real-world cryptographic deployments.

3.6. Machine Learning (ML) Inference

ML inference workloads allocate large contiguous tensors for activations and weights, making them well-suited for huge pages. However, ML class decisions affect memory traversal order in DNN layers, attention, and embedding lookup. Prior work shows attackers can infer output labels, recover weights, or extract model structure using PMU or cache-based traces [

15,

17]. Thus, evaluating hugepages in cryptographic leakage must also consider ML leakage implications.

4. Experimental Setup

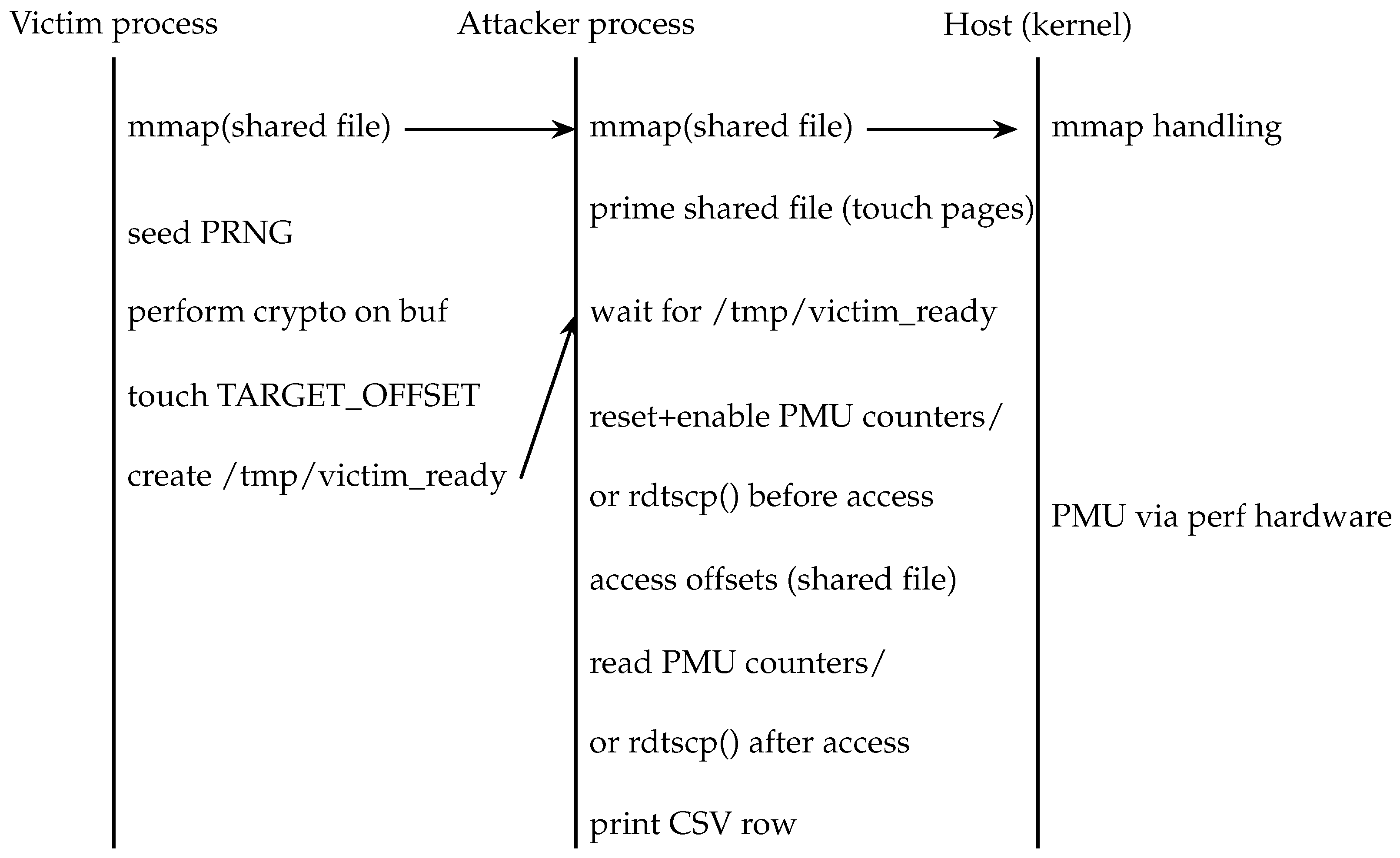

We evaluate page-level side-channel leakage using a custom attacker/victim pipeline built from three components: attacker, victim, and machine learning classifier, as shown in

Figure 1. The pipeline simulates inference-style workloads by issuing repeated, key-dependent memory accesses from the victim while the attacker records microarchitectural activity via Performance Monitoring Unit (PMU) counters and timing-based leakage using the rdtscp() counter; these traces are then aggregated and used for classification and leakage analysis.

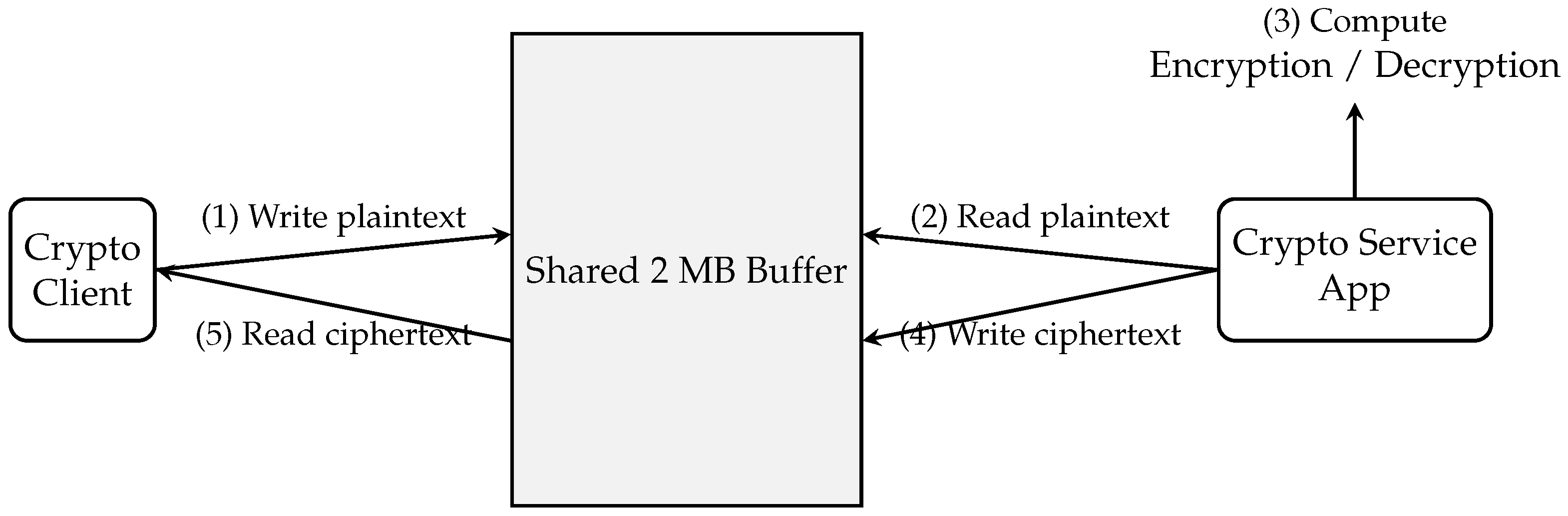

Although our experimental setup abstracts the full complexity of cryptographic libraries, its structure (as shown in

Figure 2)—reading plaintext from shared memory, performing encryption, and writing ciphertext—faithfully represents the dominant leakage mechanisms of real-world implementations. In deployed cryptographic systems, data movement across memory pages (e.g., key loading, block I/O, and ciphertext writes) generates observable TLB and cache activity that often dominates side-channel leakage. Our framework isolates this process using a controlled

read–compute–write cycle, allowing precise attribution of leakage sources.

Figure 2 explicitly illustrates this workflow by separating the roles of the crypto client, the cryptographic service, and the shared memory buffer. The client first writes plaintext data—either as a large file or as streamed input—into a shared buffer mapped to a 2 MB huge page. The cryptographic service then reads this data from the buffer, executes the encryption or decryption algorithm, and writes the resulting ciphertext back into the same shared memory region. For encryption of large data chunks in a file or streamed data, the plaintext buffer and the resulting ciphertext buffer dominates the memory usage. This part is isolated into the shared file mapped into a hugepage. Compute cycle performs the encryption algorithm followed by the write cycle that writes into a hugepage. This is a faithful replication of a cryptographic algorithm into a framework that facilitates experiments with multiple cryptographic algorithms.

Importantly, this design captures two distinct leakage channels.

(1) PMU-based leakage (aggregate microarchitectural effects). Standard hardware performance counters (e.g., cpu-cycles, cache-misses, branch-misses) capture coarse-grained microarchitectural variation across the entire victim execution. These events reflect instruction-, data-, and control-flow– dependent differences during the computation phase in addition to effects from page reads and writes. Because PMU counters are architecture-portable and do not directly expose TLB-hit or TLB-miss timing, they provide a broad but lower-resolution view of leakage that aggregates all microarchitectural behaviors. Thus, PMU-based leakage is a coarse-grained indicator of how page size influences overall side-channel visibility.

(2) Timing-based leakage (fine-grained TLB Prime+Probe analogue). To directly measure translation-sensitive leakage, we also evaluate a timing-centric channel using the rdtscp() instruction to record precise per-access latency. This mirrors classical Prime+Probe attacks: the attacker primes translation structures, the victim executes, and the attacker measures probe latency that reveals TLB hits, TLB misses, and page-walk collisions. In our model, translation-sensitive effects arise only from the shared-file plaintext read and ciphertext write phases— meaning that the timing leakage we observe represents a lower bound on the full leakage surface of a complete cryptographic implementation.

Together, these two channels provide a faithful yet analytically tractable view of how page-size configuration (4 KB vs. 2 MB) influences side-channel behavior in cryptographic workloads: PMU counters capture global execution effects, whereas rdtscp() exposes fine-grained translation timing analogous to classic TLB Prime+Probe attacks.

Our experiments assume an unprivileged attacker co-located with the victim process on the same physical machine. The attacker’s capabilities and constraints are summarized as follows:

Access to standard PMU events. The attacker may read a limited set of architecture-exposed performance counters (e.g., cpu-cycles, cache-misses, branch-misses) through the Linux perf_event_open interface without requiring elevated privileges. Only standardized, portable PMU events are used, and no model-specific or raw MSR-programmed counters are assumed.

Access to fine-grained timing via rdtscp(). The attacker may measure per-access cycle latency using the unprivileged rdtscp() instruction. This provides a timing channel analogous to a TLB Prime+Probe-style measurement, but only at user-space granularity.

Shared-memory mapping with the victim. The attacker and victim map the same 2 MB file region into user space, enabling the attacker to prime and probe translations for pages that the victim may subsequently access. No privileged manipulation of page tables or kernel structures is assumed.

CPU co-location and affinity. Both processes run on the same physical core via sched_setaffinity, ensuring that PMU measurements reflect the victim’s microarchitectural activity without interference from core migration or scheduling noise.

No access to victim secrets or code. The attacker does not observe the plaintext, ciphertext, or cryptographic keys. Only aggregate microarchitectural footprints generated by the victim’s activity are available for analysis.

This threat model reflects realistic attacker capabilities in user-space environments such as local multi-process systems, containers, and cloud VMs where unprivileged PMU access and fine-grained timing are permitted. It also provides a consistent foundation for evaluating how page-size configuration (4 KB vs. 2 MB) influences observable side-channel leakage.

4.1. Mappings and Page Sizes

The attacker and victim both

mmap the same shared backing file of size

bytes (2 MB). The file therefore covers 512 standard 4 KB pages in the process address space; as shown in

Figure 3, we run two mapping configurations that differ only in how the kernel backs those virtual addresses:

4 KB (standard pages): the file is mapped using a normal mmap (no MAP_HUGETLB) so the kernel backs the region with 512 independent 4 KB Page Table Entries (PTEs). This is our baseline: attacker and victim touch identical byte offsets, but the kernel/hardware treat each 4 KB page separately (TLB entries, page-walks, etc.).

2 MB (huge pages): the file is mapped so it is backed by true 2 MB hugepage PTE (each hugepage covers entire 512 × 4 KB region). This is done by reserving and mounting hugepages on the host. In this configuration, a single TLB entry covers the entire 2 MB region.

Figure 3.

Comparison of TLB mappings under 4 KB and 2 MB pages. Each 2 MB TLB entry covers 512 contiguous 4 KB regions, reducing translation pressure and page walks.

Figure 3.

Comparison of TLB mappings under 4 KB and 2 MB pages. Each 2 MB TLB entry covers 512 contiguous 4 KB regions, reducing translation pressure and page walks.

To run the 2 MB experiment we reserve and mount hugepages on the host (root required), for example:

sudo sh -c ’echo 512 > /proc/sys/vm/nr_hugepages’

sudo mkdir -p /mnt/hugepages

sudo mount -t hugetlbfs nodev /mnt/hugepages

truncate -s 2M /mnt/hugepages/tlbtestfile_2mb

To ensure that the two mapping configurations are directly comparable, we use the same 2 MB backing file for both the 4 KB (baseline) and 2 MB (hugepage) experiments. Using the identical file keeps user-space offsets, address arithmetic, and code paths identical while allowing the kernel to back the virtual addresses either with 512 independent 4 KB PTEs or with (pre-reserved) 2 MB hugepages. Critically, this design also guarantees the same number of measured accesses in both settings: the attacker and victim iterate over the same set of 512 distinct 4 KB page offsets, and each offset is touched for 25 independent repetitions. Thus, for every experimental key we collect

which makes aggregated comparisons (means, trimmed-means, classifier training, etc.) statistically comparable across the 4 KB and 2 MB experiments.

4.2. Victim Behavior

The victim maps a 2 MB shared file (mmap, MAP_SHARED) but performs its work on a single 4 KB page chosen randomly per experimental run from the 512 pages in the mapping. For example, if TARGET_OFFSET = 1572864 (bytes) it corresponds to page index (page #385 in one-based numbering). For reproducibility, we fixed the selected page indeices per run. For each run, it seeds the PRNG deterministically from the provided hex key, selects the requested mode (aes-gcm, aes-ecb, aes-cbc, chacha20, rsa-2048, ecc-p256, rsa-raw-256, ecc-ecies-256), and then:

- 1.

reads the plaintext from the mapped page starting at TARGET_OFFSET (full 4 KB for page-sized modes; first 256 B for small-block modes);

- 2.

executes the cryptographic kernel over that buffer (e.g., AES/ChaCha20 on 4 KB; RSA-2048 hybrid or ECC-P256 hybrid on 4 KB; RSA-RAW-256 or ECIES-256 on 256 B);

- 3.

writes the result to a temporary file and drops a “/tmp/victim_ready” flag to synchronize with the attacker.

The victim is pinned to the same CPU core with attacker via sched_setaffinity.

4.3. Attacker Measurement

4.3.1. PMU-Based Measurements

Attacker measurements were collected on a local Intel® Core™ i5-6500 (Skylake, 4 cores, base up to 3.6 GHz) development machine. The CPU exposes a set of hardware performance monitoring events (e.g., cpu-cycles, instructions, ref-cycles, cache-references, cache-misses, branch-instructions, branch-misses, and memory load/store events) through the kernel perf subsystem. We instrument the attacker process using Linux perf (via perf_event_open) to gather eight PMU-derived features per measurement (recorded as ev00–ev07 in the CSV traces).

We selected these eight counters to cover orthogonal microarchitectural effects that are likely to correlate with key-dependent memory activity: (1) cpu-cycles—coarse timing; (2) instructions—instruction throughput differences; (3) ref-cycles—stable cycle reference; (4) cache-references and (5) cache-misses—cache traffic and eviction/occupancy changes; (6) memory loads/stores—memory access intensity; and (7–8) branch-instructions/branch-misses—control-flow differences. Together these capture timing, data-flow, and control-flow signals used by downstream classifiers.

We opted to use these standard hardware events (via perf) rather than low-level raw/model-specific event encodings for several pragmatic reasons. Raw events can indeed expose more specialized counters (including some page-walk or TLB micro-events) but they are model-specific, fragile, and harder to reproduce: raw encodings require precise knowledge of the CPU’s event MSR encodings, often need elevated privileges to program reliably, vary across generations and vendors, and are more likely to be multiplexed or filtered by platform microcode. In contrast, the standardized events exposed by the kernel are far more portable across machines and OS versions, can be collected with user-level privileges for the attacker process (subject to perf_event_paranoid settings), and are simpler to audit and reproduce across experimental runs and reviewers’ systems. For these reasons we prioritized portability, reproducibility, and ease of collection for the main body of experiments.

A few practical notes that influenced collection and interpretation: (i) Skylake processors typically provide 4 programmable PMU counters plus several fixed counters (so roughly 7–8 hardware counters per core without multiplexing); requesting more events than supported triggers kernel time-multiplexing of counters, which can reduce temporal resolution. We therefore verified event availability under /sys/bus/event_source/devices/cpu/events and with perf stat -v, (ii) Occasional near-zero values indicated unsupported events or negligible signal for the microbenchmark; such cases were checked against the sysfs listing and re-run with alternate counters. (iii) Measuring the attacker process via perf requires only user-level sampling of the process itself, which simplifies experimental setup compared to system-wide tracing that can require root or relaxed perf_event_paranoid settings. These design choices produced a compact, portable fingerprint per repetition that supports the 1-vs-rest classification experiments reported in the paper.

4.3.2. Timing-Based Measurements

In addition to PMU-based measurements, we also implement a timing-centric attacker using the

rdtscp() instruction to record

per-access cycle latency. Whereas PMU counters provide aggregate microarchitectural statistics over an entire encryption operation,

rdtscp() exposes fine-grained latency differences triggered by TLB hits, TLB misses, and page-walk contention between attacker and victim accesses. This mirrors classical Prime+Probe attacks on caches and TLBs ([

14,

25,

26]): the attacker first primes the translation structures, the victim runs, and then the attacker probes the same address while logging cycle-level access time.

From the raw CSV logs we construct features as follows:

- 1.

Group raw samples by (key_id, page_offset).

- 2.

For each (key, page) grouping, we compute the mean across the 25 repetitions of each recorded measurement counter. This yields an 8-dimensional feature vector for the PMU-based setting, and a 1-dimensional feature vector when using timing-based (rdtscp) measurements.

We evaluate eight cryptographic modes that appear as victim workloads:

AES: CBC, ECB, GCM (key lengths: 128/256 bits as used);

ChaCha20 (typical 256-bit key);

Elliptic-curve-based: ECIES-256 and P-256 signature/decryption flows;

RSA: 2048-bit (standard) and a RAW-256 variant used as an experimental short-key workload.

4.4. Machine Learning Pipeline and Classification

To quantify information leakage from attacker-observable signals, we implemented an exhaustive key-classification framework in Python (version 3.11.5). For PMU-based experiments, each sample consists of the aggregated hardware-counter vector

ev00–

ev07, grouped by

(cryptographic mode, key_id, offset) and averaged across repetitions, producing one eight-dimensional feature vector per (key, page-offset) example. For each cryptographic mode, we train and evaluate a small feed-forward neural network based on

scikit-learn’s

MLPClassifier. The model uses two hidden layers of sizes (64, 32) with ReLU activation and Adam optimization, and includes optional PCA dimensionality reduction for regularization [

27,

28,

29,

30]. PMU-based experiments therefore use the standardized pipeline:

with hyperparameters selected via grid search over learning rate and L2 penalty.

In addition to the PMU modality, we also evaluate a

timing-based TLB leakage variant using per-access cycle counts measured via

rdtscp(). In this setting, each sample is represented by a single scalar feature—the averaged probe latency—i.e.,

. Because PCA is not meaningful in one dimension, the timing-based classifier uses a simplified pipeline

while keeping all other training, cross-validation, and evaluation procedures identical to the PMU-based setup. This variant tests whether fine-grained access latency alone encodes key-dependent information, serving as a direct analogue to Prime+Probe-style TLB timing attacks.

To evaluate discriminability, we adopt a one-vs-rest protocol where the classifier learns to distinguish each target key from all remaining keys (e.g., vs. ). For robustness, we remove the highest and lowest test accuracies across repetitions and report the trimmed-mean accuracy. Cross-validation uses a three-fold StratifiedKFold split to maintain class balance, with an independent 50% held-out test set for final evaluation.

This MLP-based approach offers a nonlinear yet lightweight baseline for studying side-channel leakage. The model captures correlations among timing-, cache-, and control-flow–related events without requiring large datasets. Compared to more complex models such as CNNs or random forests, the MLP provides strong performance while preserving interpretability and computational efficiency. All classifiers operate purely on user-space–accessible attacker measurements, requiring no privileged access to raw hardware counters.

In addition, we selected the MLP hyperparameters through a small grid search over learning rate and L2 regularization, using a three-fold stratified cross-validation procedure for each cryptographic mode. The hidden-layer sizes (64, 32) were chosen after confirming empirically that deeper or wider networks did not improve accuracy, while smaller networks slightly degraded performance. This yielded a stable and reproducible configuration that is appropriate for the low-dimensional PMU and timing feature spaces used in our study.

4.5. Page-Level Leakage Experiments

To evaluate whether the victim’s memory accesses reveal which page was touched during cryptographic execution, we designed a pair of attacker–victim experiments targeting page-index leakage at both 4 KB and 2 MB granularities. These experiments were conducted using two attacker-side measurement modalities: (i) Performance Monitoring Unit (PMU) counters and (ii) precise timing instrumentation via rdtscp().

In both experiments, the attacker:

- 1.

Primes all pages in the shared region.

- 2.

Waits for the victim to perform a page access.

- 3.

Probes each page again and records its measured access latency using PMU or rdtscp().

For the PMU-based experiments, the attacker records the standard hardware events (ev00–ev07) described earlier, and these aggregated feature vectors form the input to the classification pipeline. The victim performs controlled accesses to pages within a shared memory-mapped region, and the attacker attempts to infer the victim’s accessed page index from the PMU signatures alone.

Two PMU-based configurations are evaluated:

4 KB mapping: the victim operates on standard 4 KB pages, issuing a single 4 KB access for each example.

2 MB mapping with 4 KB offsets: the victim maps a 2 MB hugepage-backed region but still performs accesses at 4 KB granularity inside this region.

2 MB mapping with 2 MB offsets: the victim performs accesses at 2 MB granularity across multiple 2 MB regions. The attacker maps and measures one 2 MB region at a time, then advances to the next.

To approximate a classic Prime+Probe-style TLB experiment, we also conduct a timing-based variant using the rdtscp() instruction, which provides cycle-accurate per-access latency. The same three granularities evaluated in the PMU-based setting (4 KB pages, 4 KB offsets inside a 2 MB region, and 2 MB region-level accesses) are also used here.

Across both modalities, the goal of the page-level leakage experiments is to determine whether attacker-observable microarchitectural signals—either coarse-grained PMU activity or fine-grained per-access timing—encode enough information to identify which page the victim accessed during its cryptographic workload.

5. Results

5.1. Key-Class Classification (PMU-Based)

Table 1 reports trimmed-mean test accuracy for one-vs-rest key classification per cryptographic mode under the two mapping configurations. Each entry reflects models trained on the aggregated PMU features (

ev00–

ev07) averaged over 25 repetitions for each (key, page-offset) example, with a 50% held-out test split and three-fold stratified CV for hyperparameter selection [

31,

32].

Overall, PMU-based key classification sits well above random guessing (0.5), with accuracies typically in the 0.74–0.83 range across modes. Comparing 2 MB huge pages to 4 KB mappings, the differences are modest: AES-GCM and RSA-RAW show a consistent but moderate advantage for 2 MB, AES-EBC and ECC modes exhibit higher accuracy in 4 KB mappings. This suggests that, at least for our setup, using 2 MB huge pages does not qualitatively change the attacker’s PMU-based key distinguishability.

5.2. Key-Class Classification (Time-Based)

We next repeat the exhaustive one-vs-rest key classification, but using only the attacker’s execution time measured by rdtscp() as the only one feature.

Table 2 reports the mean test accuracy across these four one-vs-rest splits for 2 MB and 4 KB mappings.

Time-based key classification also remains well above random guessing for all modes, with accuracies in the 0.73–0.79 range. Comparing 2 MB huge pages to 4 KB mappings, the differences are modest: AES-GCM and ECC-P256 exhibit a slight advantage for 2 MB, whereas AES-ECB shows somewhat higher accuracy under 4 KB, and the remaining modes are essentially comparable across page sizes. This mirrors the PMU-based results in

Table 1, suggesting that the choice between 2 MB and 4 KB mappings does not fundamentally change the attacker’s ability to distinguish keys using either PMU counters or timing alone.

5.3. Page-Level Leakage

We next evaluate whether cryptographic executions leak the page number accessed by the victim. Page-index identification is tested at both 4 KB and 2 MB granularity using two attacker-side modalities: (i) PMU-based measurements and (ii) timing measurements via rdtscp().

Using the aggregated feature vectors (ev00–ev07) and the same neural classifier, we measure how well the attacker can infer which page was accessed.

Results:

4 KB configuration (predict 4 KB page index): accuracy = 3.6%.

2 MB mapping, 4 KB offset (predict 4 KB page index): accuracy = 3.7%.

2 MB mapping (predict 2 MB page number across 20 regions): accuracy = 3.6%.

These values are all near chance for the corresponding label spaces, indicating weak or negligible PMU-based page-index leakage.

To approximate a traditional Prime+Probe TLB attack, we repeat the experiment using cycle-accurate timing via rdtscp(). After priming the region, the attacker measures per-page access latency following the victim’s access.

Measured accuracies:

4 KB configuration (predict 4 KB page index): trimmed-mean accuracy = 2.1%.

2 MB mapping, 4 KB offset (predict 4 KB page index): trimmed-mean accuracy = 1.6%.

2 MB mapping (predict 2 MB page number across regions): estimated accuracy = 1.5%, consistent with 1-in-20 chance.

Again, all results are effectively at random-chance level, despite using high-resolution timing.

Across both PMU-based (coarse-grained) and timing-based (fine-grained) experiments, page-index prediction remains extremely weak. This near-random accuracy is primarily due to the fundamental limitations of the chosen measurement modalities for this specific task. Specifically, the attacker-visible signals lack sufficient spatial resolution to reliably distinguish which individual memory page was accessed by the victim. PMU counters capture only aggregated microarchitectural activity (such as overall cycles or cache misses) and are inherently too coarse-grained to isolate or precisely resolve fine-grained TLB hit/miss behavior at the 4 KB or 2 MB page boundary. Meanwhile, rdtscp() exposes per-access latency but still yields a high-variance, noisy signal that fails to strongly correlate with the specific page index the victim accessed. As a result, the available measurements lack sufficient page-specific resolution, and repeated executions do not yield stable features that support reliable page-index classification.

These findings indicate that—under our controlled experimental design—neither PMU counters nor timing measurements reveal reliable page-index information at either 4 KB or 2 MB granularity. Accordingly, we treat page-level identification as a low-signal task in this work and direct the main analysis toward key-class leakage, where measurable signal exists.

5.4. Runtime/Overhead Snapshot

We measured per-run execution cost using the

cpu-cycles PMU counter (recorded as

ev00 in the CSV traces). For each (mode, key) run we aggregated the

ev00 readings across the 25 repetitions and then averaged across all evaluated runs to produce a single representative cycle count per configuration (2 MB vs. 4 KB). Relative difference was computed as

Using this metric the 2 MB huge-page configuration required on average

fewer CPU cycles per victim run than the 4 KB baseline (i.e.,

in favor of 2 MB).

Two practical notes: (1) these numbers come from the standardized PMU counter (cpu-cycles) and therefore reflect processor-cycle work rather than high-level wall-clock time; (2) we report trimmed/averaged statistics (removing extreme outliers) to reduce influence from rare system perturbations. In informal checks the cycle-based speedup was consistent with small improvements in wall-clock runtimes, but we conservatively present the PMU-derived figure here because it has the highest-resolution and least affected by OS scheduling jitter.

6. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that using 2 MB huge pages can improve runtime efficiency without amplifying measurable side-channel leakage. Across all cryptographic workloads, the 2 MB configuration consistently achieved a mean 11% reduction in CPU cycles (measured by the cpu-cycles PMU counter) relative to the 4 KB baseline. This speedup is consistent with the expected effect of reducing translation overhead—fewer TLB misses and page-table walks when the entire 2 MB region is covered by a single page translation entry. Importantly, this performance improvement does not come at the cost of increased leakage: key-classification accuracies between 4 KB and 2 MB mappings differ only slightly (typically within a few percentage points), and page-index identification remains at random-chance levels in both cases.

Although huge pages alter the hardware’s memory-translation behavior, they primarily reduce noise rather than exposing new microarchitectural side channels. In our setup, the victim always accesses a single 4 KB page per run inside the 2 MB mapping, so address-translation structures (e.g., TLBs) remain stable between repetitions. Since our PMU features focus on general microarchitectural events—cycles, cache references/misses, and branch activity—rather than raw TLB-specific events, the overall leakage surface does not expand under huge-page mappings. The resulting classifier performance indicates that huge pages neither obscure nor amplify the extractable information about secret-dependent operations.

Real cryptographic routines—such as AES, RSA, or ECC—rarely operate on a single contiguous buffer. Instead, they perform sequences of reads from multiple memory pages to fetch keys, lookup tables, or plaintext blocks, followed by computations on intermediate states, and finally writes of ciphertexts or authentication tags. These read–compute–write cycles constitute the dominant sources of side-channel leakage in deployed cryptographic libraries, as each stage interacts differently with caches, TLBs, and execution pipelines.

In our experimental framework, we abstract the full cryptographic process into a controlled and reproducible model that concentrates on the translation-sensitive components of execution within a shared memory-mapped region. Specifically, we emulate only the plaintext read and ciphertext write phases, which directly invoke page translations and memory traffic—making them the primary contributors to TLB-driven leakage under different page sizes (4 KB vs. 2 MB). The PMU event counters (e.g., cpu-cycles, cache-misses, branch-misses) simultaneously capture aggregate microarchitectural effects from the entire execution, including arithmetic and control-flow variations during the intermediate computation phase. Consequently, the PMU-based measurements captures additional, computation-driven leakage beyond translation effects. In contrast, the timing-based TLB leakage is primarily influenced by page size and is limited to shared-file read and write activities, and thus represents a conservative lower bound on the total side-channel leakage of a full cryptographic system.

While our model abstracts the full cryptographic process, it provides an architecture-agnostic and analytically tractable benchmark that faithfully mirrors the key structural phases of real cryptographic operations—reads, computation, and writes. This controlled design enables fine-grained analysis of how page granularity influences both performance and leakage, while maintaining full experimental reproducibility. It thus serves as a clean framework for isolating and studying page-size–induced side-channel effects in modern cryptographic systems.

These findings suggest that, at least for user-space software performing repeated cryptographic or inference-like workloads, enabling 2 MB huge pages can yield a tangible runtime gain without sacrificing observable side-channel resilience at the PMU level. Intuitively, fewer PTEs (Page Table Entries) with 2 MB page size increase the probability for an attacker page to collide with a victim page, thereby leaking victim memory usage information. However, since the number of PTEs for 2 MB page size reduces significantly compared to a 4 KB page size, the number of bits of information leaked is also reduced manifold. While we do not claim that huge pages universally eliminate leakage (especially for attacks explicitly targeting translation structures), in our controlled attacker–victim model the huge-page configuration preserved comparable security while offering measurable efficiency improvements.

Recent generation of processor cores such as Intel Icelake and AMD Zen 3/4 cores offer better visibility into TLB events through additional PMU events. Intel Icelake includes 8 events for DTLB. Some of these events are finer forensic granularity such as DTLB_STORE_MISSES.WALK_COMPLETED_2M_4M counting the completed page walks of 2M/4M pages or DTLB_STORE_MISSES.WALK_COMPLETED_4K for 4K size page walks. This finer-grained capture may increase the leakage. However, we believe that both 4K and 2M cases would be similarly affected, leading to similar comparative results.

The threat model and leakage channels considered in this work are most directly relevant to co-located workloads within the same operating system instance, such as containerized services or multi-process applications inside a single virtual machine. In fully isolated cross-VM settings, PMU access is often restricted, timing signals may be noisier due to virtualization, and shared hugepage-backed memory is typically unavailable without explicit hypervisor support. Here, fully isolated cross-VM settings refer to scenarios in which attacker and victim execute in separate virtual machines managed by a hypervisor. In such environments, access to hardware performance monitoring units is commonly virtualized, limited, or disabled for unprivileged guest processes to prevent cross-tenant information leakage. Similarly, high-resolution timing sources such as rdtscp() are often virtualized and affected by vCPU scheduling, migration, and hypervisor intervention, which reduces the fidelity of fine-grained timing observations. Although multiple VMs may access the same storage backend, file-backed huge pages do not typically result in shared physical memory across VM boundaries unless explicit hypervisor-supported shared-memory mechanisms are enabled. Consequently, while the absolute leakage characteristics may differ across deployment environments, the qualitative trade-offs analyzed here—between page granularity, translation behavior, and attacker-visible microarchitectural effects—remain informative for understanding the security–performance implications of hugepage adoption and motivate future evaluation in cloud-specific configurations.

From a systems perspective, this highlights a favorable trade-off: huge pages enhance throughput and determinism—benefiting both high-performance and privacy-sensitive workloads—without creating new leakage vectors (detectable via standard unprivileged PMU events). Future work could explore whether similar conclusions hold under temporal (sequence-based) analysis or on newer microarchitectures with extended PMU/TLB event coverage.

7. Conclusions

This work presents a systematic evaluation of how memory page size influences the security–performance trade-off in cryptographic workloads. By comparing standard 4 KB pages with 2 MB huge pages under a realistic unprivileged attacker model, we show that huge pages provide consistent performance benefits while preserving comparable attacker-visible leakage at the PMU and timing levels.

Our findings indicate that, within the scope of the studied threat model and measurement modalities, enabling huge pages does not introduce additional side-channel risk and therefore does not require special mitigation beyond standard side-channel defenses. More broadly, this work provides a principled framework for reasoning about page-size–induced effects in modern cryptographic systems and motivates future exploration on newer microarchitectures and cloud-specific configurations.