Role-Based Efficient Proactive Secret Sharing with User Revocation

Abstract

1. Introduction

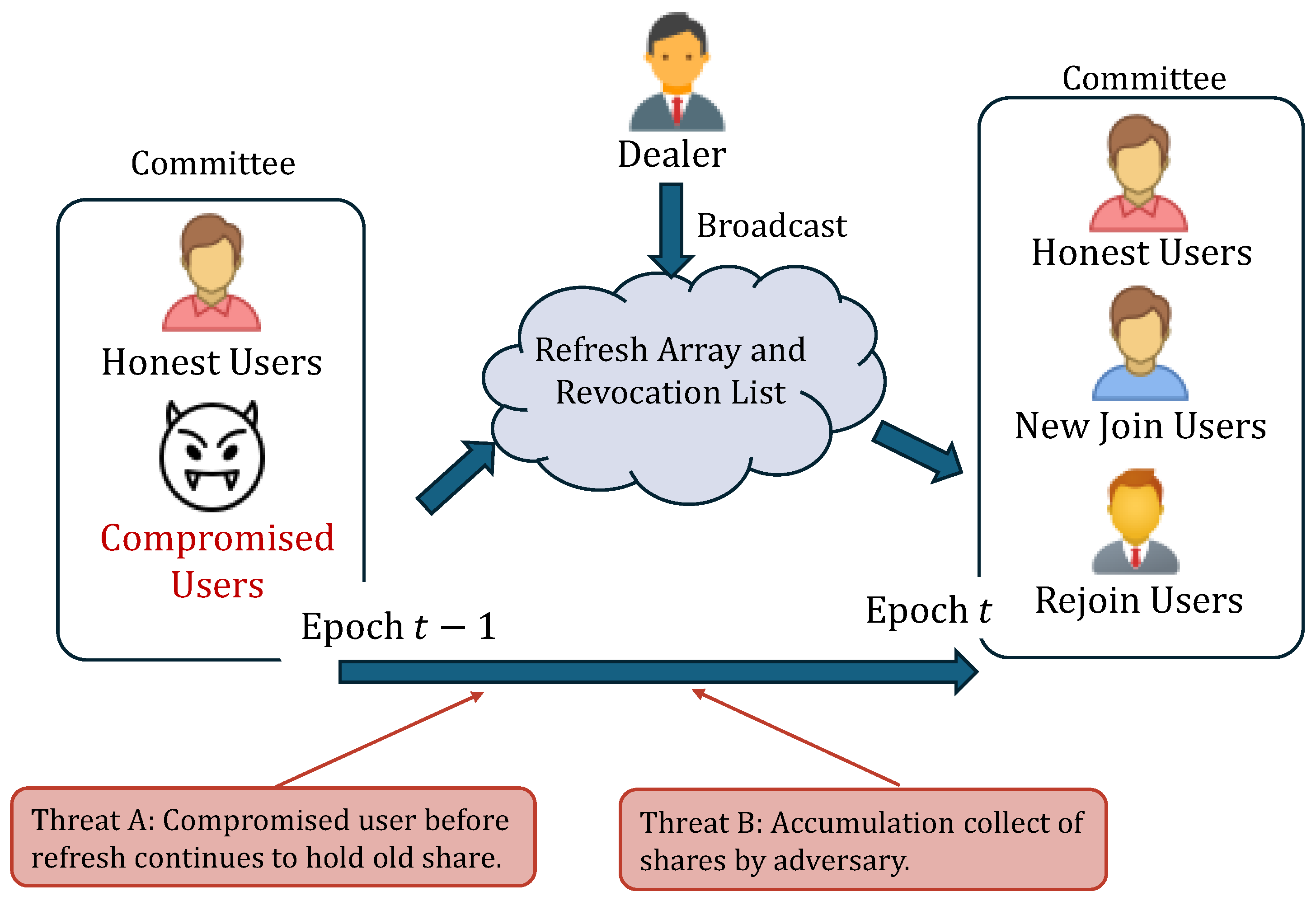

- A unified fresh revocation protocol. We extend the original non-interactive refresh mechanism by incorporating user-revocation capabilities, enabling simultaneous share refresh and valid-user-set updates through a single broadcast. In this process, a trusted dealer prepares and broadcasts a compact message containing the encrypted refresh arrays for share refresh and a hash-based valid-user set. Each user can independently refresh their shares by performing homomorphic computations on the encrypted arrays, whereas the shares of revoked users are rendered cryptographically invalid.

- Role-based dynamic membership management. In this study, users are categorized into three roles during each epoch to enable fine-grained dynamic user management:

- -

- Retain. Retain refers to those who are present in both epochs t and . Such users refresh their shares by performing homomorphic computations on their shares and encrypted array .

- -

- Newly Join. In this paper, newly join refers to users who join the system for the first time in epoch t. These users are provided with the encrypted array to generate their shares for this epoch.

- -

- Rejoin. Rejoin refers to revoked users who are reauthorized at epoch t. In some practical multi-party scenarios, participants may temporarily leave the system due to reassignment. Treating each return as newly join would cause avoidable overhead. To address this issue, the proposed method provides an encrypted array for those users who refresh their shares in a short absence.

- Security and efficiency. Homomorphic computations reduce dealer participation while maintaining consistency throughout refresh cycles. Our method enables dynamic threshold changes in each epoch, allowing the system to adjust its security level flexibly over time while ensuring consistent share generation. Even if a user is revoked after corruption, their past and future shares cannot be combined to reconstruct the secret. Cryptographic hashing ensures the integrity of a valid-user set and prevents unauthorized modifications.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Shamir Secret Sharing (SSS)

2.2. Proactive Secret Sharing

- Share Generation. The initial generation and distribution of shares employ SSS schemes, as detailed in Section 2.1.

- Share Refresh. During the refresh phase, each user generates refresh components for each participant, including themselves, and sends them to their corresponding users. Each user collects all of the received components along with their current share to refresh their share. This process updates the shares while preserving the original secret m.

- Reconstruction. The updated shares are combined to reconstruct the secret m using the Lagrange interpolation formula (3).

2.3. Hash Function

- Preimage Resistance. Given a digest y, it is computationally infeasible to find any x such that

- Second Preimage Resistance. Given input x, it is infeasible to find a different with .

- Collision Resistance. It is infeasible to find any pair such that .

2.4. Homomorphic Encryption

- BFV.Setup(): Given the security parameter and a multiplicative depth L, choose a cyclotomic polynomial , where d is the power of 2. Choose the ciphertext modulus q and plaintext modulus p. Define as a polynomial ring of degree d with integer coefficients. Moreover, . Generate the error distribution and key distribution over . Finally, output as the public parameters. We assume all following algorithms implicitly take as an input.

- BFV.KeyGen(): Given public parameters , sample a secret , an element , and a small noise . Set the secret key as and the public key as , where .

- BFV.EvalKeyGen(s): Given the secret key s, generate the evaluation key as , where , , and set , where is a fixed gadget vector with base G and l is the gadget dimension. Output .

- BFV.Enc(): Given a public key and a plaintext , sample a random and noise elements . Scale up the message using a factor . Output the ciphertext as , where and .

- BFV.Dec(): Given a ciphertext and a secret key , output the result .

- BFV.Add(): To add two ciphertexts , output the ciphertext .

- BFV.Mult(): Given two ciphertexts , compute first by , , and . Then, calculate with as follows:

- -

- Apply gadget decomposition:

- -

- Output the ciphertext.

- ThHE.KeyGen(): Given the public parameters by running BFV.Setup, output n secret keys and a joint public key .

- ThHE.Enc(): Encrypt the message under the public key by BFV.Enc; output ciphertext .

- ThHE.Eval(): Given the joint public key and evaluation key by running BFV.EvalKeyGen, output the evaluated ciphertext . Similar to the base BFV scheme, the evaluation function f can be either homomorphic addition or multiplication.

- PartDec(): Given a ciphertext under and a secret share of the key , generate a decryption component as .

- Combine(): Combine at least k partial decryption to reconstruct m as .

2.5. NUSS

- Setup. Given public parameters consisting of SSS and ThHE, the dealer generates share for each user i. Here, ThHE.Enc(), where is the computation of (1).

- Refresh. The refresh phase is divided into two parts depending on the entity involved: the dealer side and the user side.

- -

- Dealer side. Dealer generates and broadcasts the encrypted array , which encodes the new parameters corresponding to the new threshold.

- -

- User side. Each user computes the new share by performing the following operations:where is the old share and i is the user’s public index.

- Recover. By collecting new threshold number of shares and performing PartDec in ThHE, the requester can reconstruct the message.

3. Design of Our Proposal

3.1. Notations

3.2. Dynamic Membership Models

3.2.1. Role-Based User Model

- Retain (). Users who belong to both the current valid set and the previous valid set , defined as . For each user , the user i’s epoch satisfies , where denotes the current epoch of . The dealer generates an array for such users’ share refresh.

- Newly join (). Users who join the system for the first time in the epoch t, defined as , where denotes the union of all valid-user sets prior to epoch t. For each user , satisfies . The dealer generates array for such users’ share refresh.

- Rejoin (). Users who previously revoked but rejoin in the current epoch valid set , defined as , where is revocation list maintained by the dealer. For each user , . The dealer offers either or for such users based on the duration of the user’s absence. Note that is the same array used for . Users in represent participants who experienced short absences and thus stayed within the secure refresh duration. Such users do not require full redistribution as users in . Therefore, those shares can be refreshed using a specific array without incurring additional overhead.

3.2.2. Epoch-Based Scheme

- : The takes the security parameter and outputs the public parameters.

- : Given the public parameters, generates and distributes initial shares for each user in the first epoch.

- : allows valid users to update their shares from epoch to epoch t non-interactively.

- : Determines user membership status for the new epoch.

- : Reconstructs the secret from authorized set from epoch t.

4. Protocol Details and Construction

4.1. Setup Phase

- 1.

- SSS parameters.

- The plaintext modulus p is used to define the finite field for SSS and also as the plaintext space in ThHE.

- Fix the initial threshold k and total number of users n. Here, k denotes the initial threshold (e.g., ), which corresponds to the first element of the threshold sequence defined in Section 3.2.

- 2.

- ThHE parameters.

- Instantiate ciphertext modulus q and the polynomial ring . Moreover, and are distributions of ThHE keys and errors over polynomial ring , respectively.

- p denotes the plaintext modulus of ThHE, where .

- 3.

- Public parameters instantiate a hash function and epoch t.

4.2. Share Generation

- 1.

- Polynomial Sampling: Sample as the coefficients of polynomial for the initial epoch with secret .

- 2.

- Share Computation: In SSS scheme, is the share distributed to each user. In this proposal, each user uses ThHE to reprocess the .

- Dealer generates ThHE key pairs for n users: , where and , by performing ThHE.KeyGen(), where denotes i-th Lagrange coefficient.

- Reprocess with :

- 3.

- Distribute the share to i-th user:

4.3. Revoke and Refresh

4.3.1. Dealer Side

- 1.

- Revoke by dealer. The valid-user set is determined by the dealer at epoch t, and each user ID i is encoded using a hash function.where

- 2.

- Refresh by dealer. In the refresh procedure, the dealer generates the arrays required for user share-refresh operations based on user roles, which are determined by the dealer. A new threshold is set for epoch t. The dealer’s operations in the refresh phase are described as follows.

- Generates new polynomial for new scheme :

- Generates arrays for share refresh. Based on each user’s epoch and the valid-user set’s epoch , the dealer computes the corresponding arrays, as shown in Table 3.

- -

- For retain users , who hold valid shares from epoch , the dealer computes the difference between the polynomial coefficients of epochs t and to construct the array .

- -

- For newly join users , the dealer generates the array for their share refresh. Unlike users in or , these users do not possess any old shares. Therefore, the array contains the original secret m. Nevertheless, there is no concern about the information security as the broadcast message is encrypted by ThHE.

- -

- For each rejoin user , the dealer selects the array based on the duration of the user’s absence, as defined in Table 2. If the difference between user’s last epoch () and current epoch t exceeds the limitation (e.g., ), the users use for share refresh, which is for newly join users. Otherwise, the dealer provides for refresh process.

- Reprocess those arrays by .

- Distribute to network.

4.3.2. User Side

- 1.

- Revoke by user. z is a global random number generated from the dealer. Each user i generates a random number and calculates the function to determine their status.where , .It holds that, if and only if , i is valid user.

- 2.

- Refresh is calculated by the user as follows.

- Encrypt user ID array by :

- Calculate the encryption of array for user i’s share refresh.

- -

- If :

- -

- If :Here, since users in do not contain any old shares, is set as the encryption of zero.

- -

- If : Use the corresponding broadcast message to generate the i’s refresh array . Since the threshold is not exposed to users, each user attempts to use the corresponding array. If the attempt using fails, the user is treated as newly join and uses for share refresh.

- Compute the new encryption for user i in epoch t.

- User i updates the share for epoch t as follows.

4.4. Recover Secret

- 1.

- Compute Lagrange coefficients. For user , compute the Lagrange coefficient .

- 2.

- The ciphertext of m is generated by homomorphic computations.

- 3.

- Reconstruct the secret m.

5. Protocol Properties

5.1. Adversary Model and Security Assumptions

- Confidentiality. The secret m remains secure from unauthorized users, including revoked or corrupted participants.

- Correctness. Valid users can correctly update their shares and reconstruct the secret after refresh and revoke operations.

- Non-repudiation. Refresh and revoke procedures performed by users individually cannot be denied due to the utilization of authenticated channels and cryptographic integrity verifications.

- BFT alignment. Ensures absence duration implies exposure to fewer than malicious participants, preserving system safety.

- Information-theoretic decay. When , the old share becomes obsolete. Adversaries cannot cross-correlate old and new shares to recover the secret.

5.2. Correctness

- 1.

- Refresh Correctness. The correctness of the scheme relies on the computations in refresh process. After each user receives the encryption of the array (e.g., ), they perform the homomorphic computations on old share and arrays to obtain new share. For simplicity, we use a retain user i and the plaintext to demonstrate the correctness instead of ThHE encrypted data.

- Proof of Refresh Correctness.denotes the SSS polynomial coefficients of the shares in epoch , and denotes coefficients in epoch t, where . The old share includes

- 2.

- Revoke Correctness. The revoke phase relies on epoch check and the function , and the correctness is determined by the result of .

- Proof of Revoke Correctness.Let be a random number generated by user i. In epoch t, all users can receive the hash of valid set in epoch t and a public random number z. User i’s verification key denotes . If , there exists with such that

5.3. Non-Interactivity

6. Evaluation

6.1. Parameter Setup and Complexity Comparison

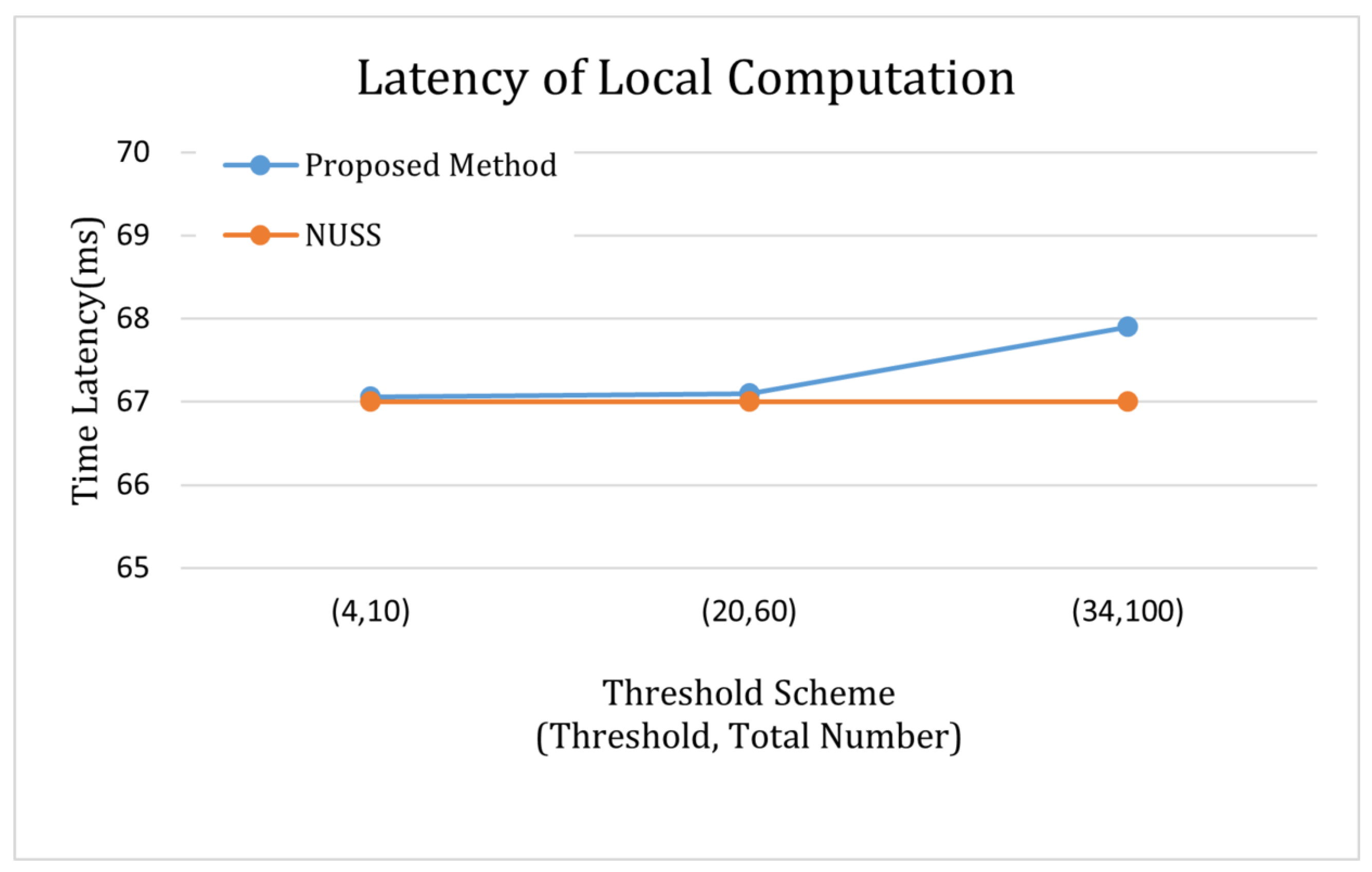

6.2. Performance Evaluation

6.2.1. Evaluation on User Side

6.2.2. Results Impact Dealer Update Strategy Setting

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shamir, A. How to share a secret. Commun. ACM 1979, 22, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, A.; Jarecki, S.; Krawczyk, H.; Yung, M. Proactive secret sharing or how to cope with perpetual leakage. In CRYPTO ’95; Coppersmith, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; Volume 963 of LNCS, pp. 339–352. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Huda, S.; Kodera, Y.; Nogami, Y. NUSS:Non-Interactive Updatable of Secret Sharing Schemes Using Homomorphic Encryption. In Proceedings of the 2024 Twelfth International Symposium on Computing and Networking Workshops (CANDARW), Naha, Japan, 26–29 November 2024; pp. 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakley, G.R. Safeguarding cryptographic keys. 1979 International Workshop on Managing Requirements Knowledge (MARK), New York, NY, USA, 4–7 June 1979; pp. 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, B.H.; Noble, D.; Rabin, T. Proactive Secret Sharing with Constant Communication. In Theory of Cryptography, Proceedings of the TCC 2023, Taipei, Taiwan, 29 November–2 December 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 337–373. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, L. A Dynamic Proactive Secret Sharing Scheme for Quadratic Functions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 25749–25761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneh, D.; Partap, A.; Rotem, L. Proactive refresh for accountable threshold signatures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Willemstad, Curaçao, 4–8 March 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 140–159. [Google Scholar]

- Raghav; Andola, N.; Verma, K.; Venkatesan, S.; Verma, S. Proactive threshold-proxy re-encryption scheme for secure data sharing on cloud. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 14117–14145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brorsson, J.; David, B.; Gentile, L.; Pagnin, E.; Wagner, P.S. PAPR: Publicly auditable privacy revocation for anonymous credentials. In Proceedings of the Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–27 April 2023; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 163–190. [Google Scholar]

- Günther, C.U.; Das, S.; Kokoris-Kogias, L. Practical Asynchronous Proactive Secret Sharing and Key Refresh. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2022. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/1586 (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Rogaway, P.; Shrimpton, T. Cryptographic Hash-Function Basics: Definitions, Implications, and Separations for Preimage Resistance, Second-Preimage Resistance, and Collision Resistance. In Fast Software Encryption; Roy, B., Meier, W., Eds.; FSE 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 3017. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Sahraei, S.; Li, S.; Avestimehr, S.; Kannan, S.; Viswanath, P. Coded merkle tree: Solving data availability attacks in blockchains. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 10–14 February 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 114–134. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, A.; Aksu, H.; Uluagac, A.S.; Conti, M. A survey on homomorphic encryption schemes: Theory and implementation. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, C.; Fabien, G. A survey of homomorphic encryption for nonspecialists. EURASIP J. Inf. Secur. 2007, 15, 13801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.; Sousa, L.; Mariano, A. A Survey on Fully Homomorphic Encryption: An Engineering Perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. 2017, 50, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaikuntanathan, V. Computing blindfolded: New developments in fully homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE 52nd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Palm Springs, CA, USA, 22–25 October 2011; pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brakerski, Z. Fully homomorphic encryption without modulus switching from classical GapSVP. In Proceedings of the Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–23 August 2012; pp. 868–886. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Vercauteren, F. Somewhat Practical Fully Homomorphic Encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2012. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2012/144 (accessed on 22 March 2012).

- Boneh, D.; Gennaro, R.; Goldfeder, S.; Jain, A.; Kim, S.; Rasmussen, P.M.R.; Sahai, A. Threshold cryptosystems from threshold fully homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2018: 38th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–23 August 2018; Proceedings, Part I 38, pp. 565–596. [Google Scholar]

- Asharov, G.; Jain, A.; López-Alt, A.; Tromer, E.; Vaikuntanathan, V.; Wichs, D. Multiparty computation with low communication, computation and interaction via threshold FHE. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT, Cambridge, UK, 15–19 April 2012; pp. 483–501. [Google Scholar]

- Bootland, C.; Cong, K.; Demmler, D.; Frederiksen, T.K.; Libert, B.; Orfila, J.-B.; Rotaru, D.; Smart, N.P.; Tanguy, T.; Tap, S.; et al. Threshold (Fully) Homomorphic Encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2025, Paper 2025/699. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2025/699 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Maram, S.K.D.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Low, A.; Zhang, Y.; Juels, A.; Song, D. CHURP: Dynamic-committee proactive secret sharing. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, London, UK, 11–15 November 2019; pp. 2369–2386. [Google Scholar]

- Vassantlal, R.; Alchieri, E.; Ferreira, B.; Bessani, A. COBRA: Dynamic Proactive Secret Sharing for Confidential BFT Services. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2022; pp. 1335–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| U | U denotes the user set. |

| denotes the valid-user set; is in epoch t. | |

| , , | Arrays broadcast by the dealer for share-refresh calculations. |

| User i’s verification key in epoch t. |

| Role | Descriptions | Epoch Relations 1 | Array |

|---|---|---|---|

| Users in . | |||

| Users added in . | |||

| Revoked users reauthorized. 2 | |||

| Array | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Array for users who are authorized in both epochs t and . . | |

| Refresh array for users who first joined in system at epoch t and rejoined users. . | |

| Refresh array for rejoined users whose absence duration is less than . . |

| Fixed Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaintext modulus (p) | 65,537 | |||

| Ciphertext modulus () | 101 | |||

| Threshold Settings by Number of Users | ||||

| Number of users (n) | 10 | 60 | 100 | |

| Threshold | Before update | 4 | 20 | 34 |

| After update | 5 | 21 | 35 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Kodera, Y.; Nogami, Y.; Huda, S. Role-Based Efficient Proactive Secret Sharing with User Revocation. Cryptography 2025, 9, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryptography9040080

He Y, Kodera Y, Nogami Y, Huda S. Role-Based Efficient Proactive Secret Sharing with User Revocation. Cryptography. 2025; 9(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryptography9040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yixuan, Yuta Kodera, Yasuyuki Nogami, and Samsul Huda. 2025. "Role-Based Efficient Proactive Secret Sharing with User Revocation" Cryptography 9, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryptography9040080

APA StyleHe, Y., Kodera, Y., Nogami, Y., & Huda, S. (2025). Role-Based Efficient Proactive Secret Sharing with User Revocation. Cryptography, 9(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryptography9040080