RP-DAD-HPLC Method for Quantitative Analysis of Clofazimine and Pyrazinamide for Inclusion in Fixed-Dose Combination Topical Drug Delivery System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Materials

2.2. Equipment

2.3. HPLC Operating Conditions

3. Procedures

3.1. Preparation of Stock and Standard Solutions

3.2. Chromatographic Properties of the Eluted Peaks

3.3. Method Validation Procedure

3.3.1. System Repeatability

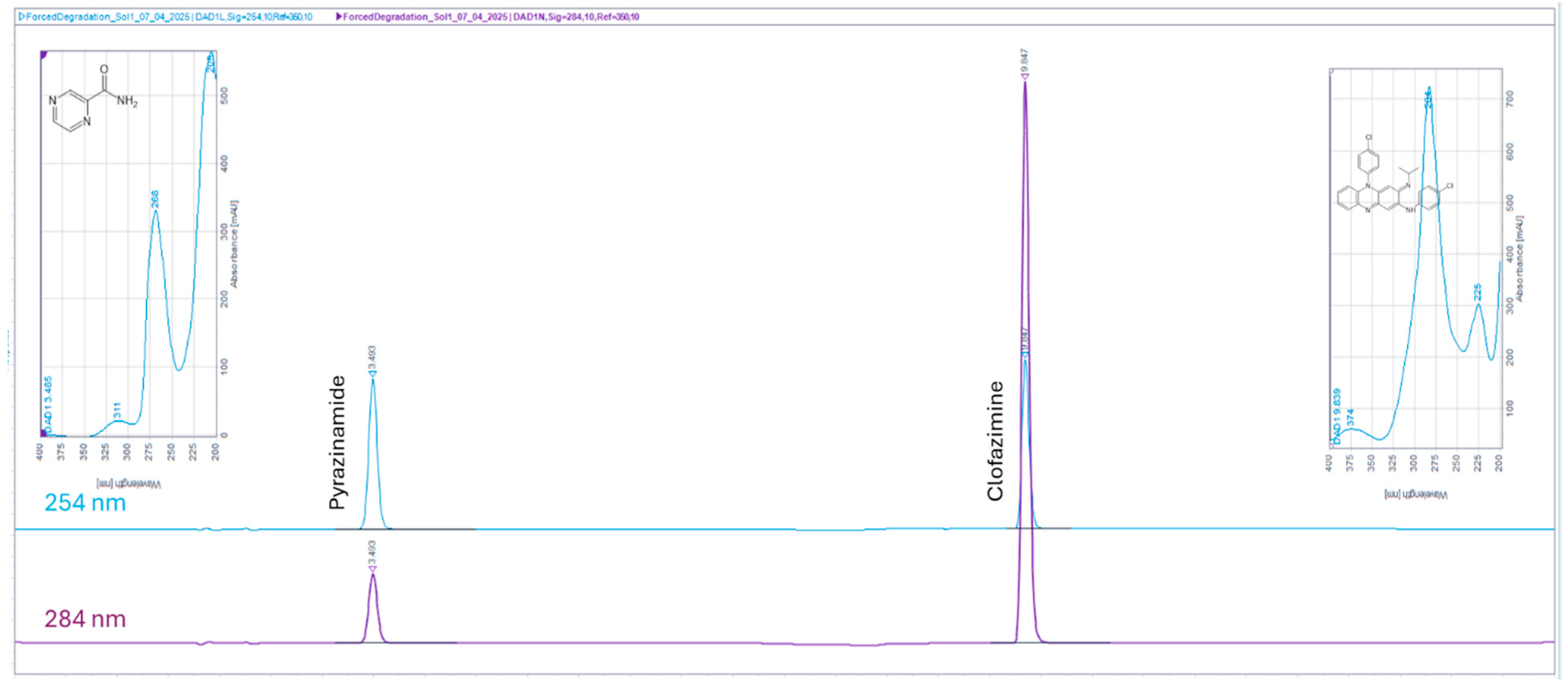

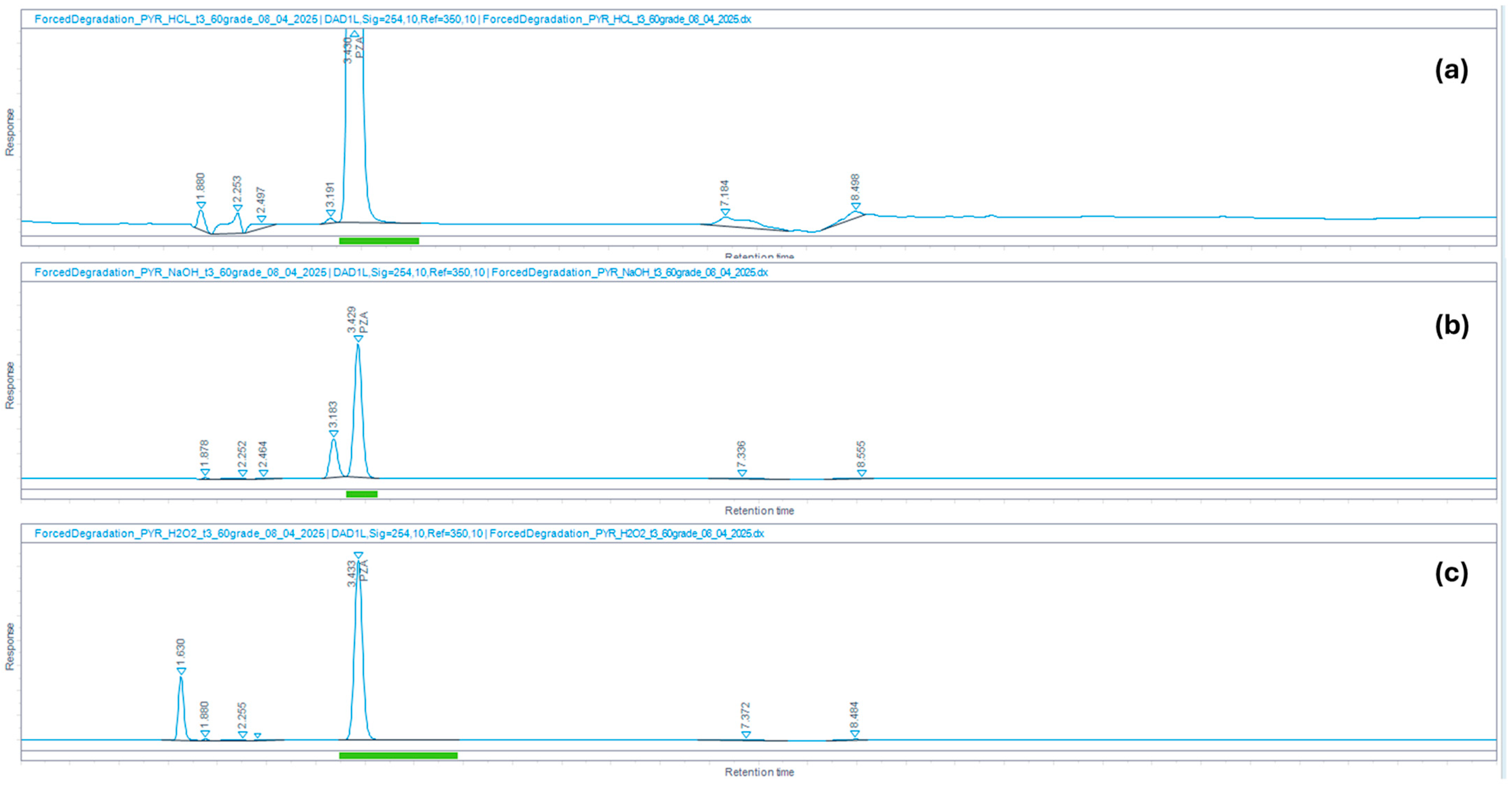

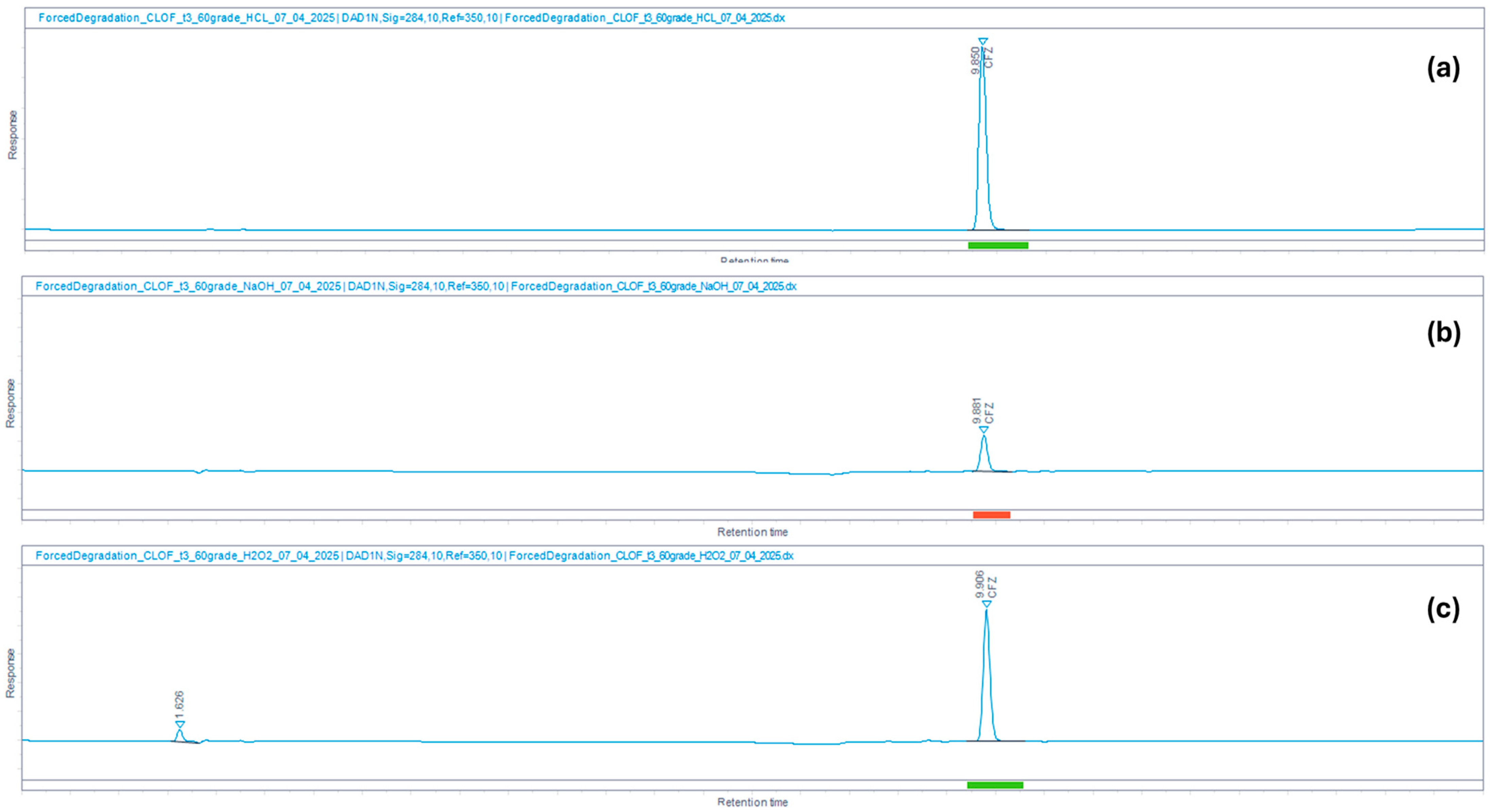

3.3.2. Specificity

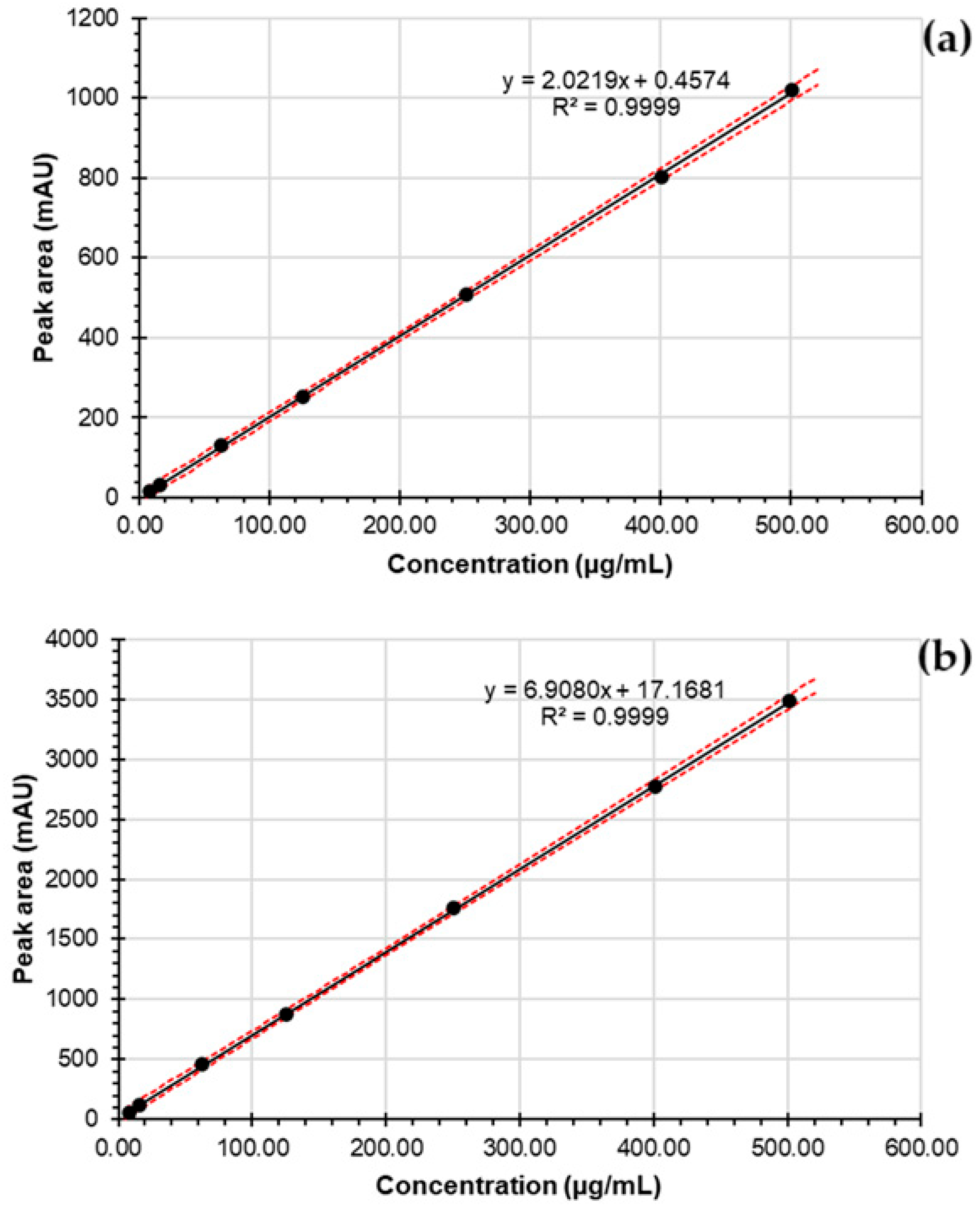

3.3.3. Linearity, Range, Limit of Detection, and Limit of Quantitation

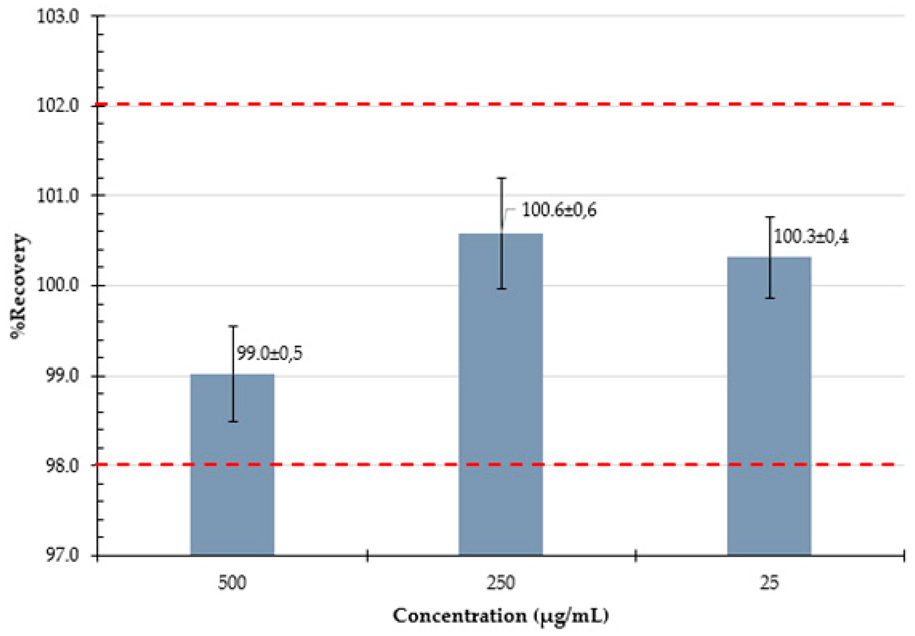

3.3.4. Accuracy

3.3.5. Intermediate Precision

3.3.6. Robustness

4. Results and Discussion

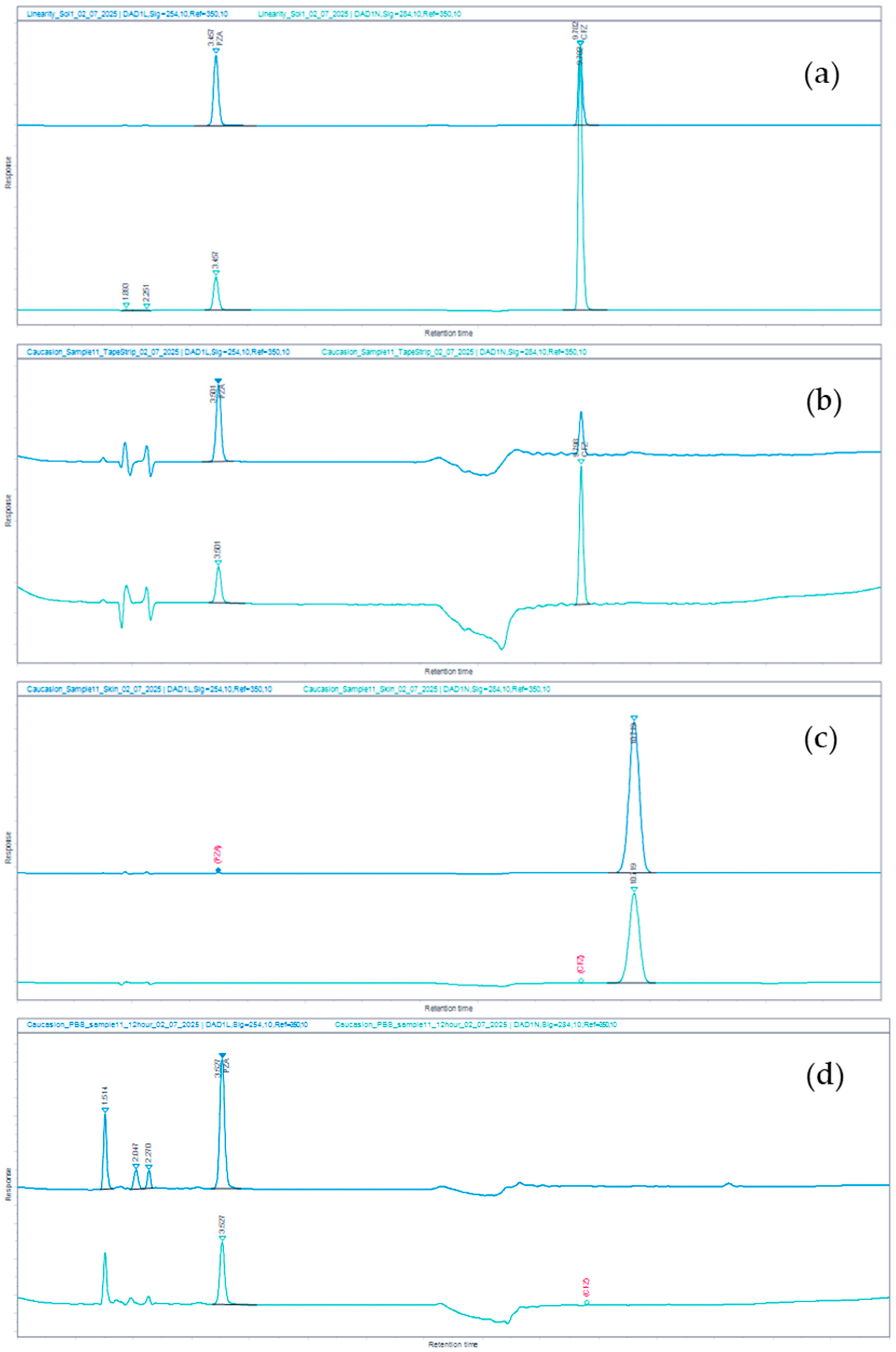

4.1. Chromatographic Analysis

4.2. Validation of the Analytical Method

| Parameter | PZA | CFZ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration range (µg/mL) | 7.8–500 | 7.8–500 | ||||||

| Regression Correlation coefficient (r2) Regression equation p-value for intercept | 0.9999 y = 2.0219x + 0.4574 0.86 | 0.9999 y = 6.9080x + 17.1681 0.07 | ||||||

| Limit of detection (LOD) (µg/mL) | 7.14 | 6.33 | ||||||

| Limit of quantitation (LOQ) (µg/mL) | 21.62 | 19.18 | ||||||

| Accuracy Expressed as % recovery at ~500, 250, and 25 µg/mL |  |  | ||||||

| Intermediate precision Determined at 3 levels, over 3 days | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | ||

| Level 1 (~25 µg/mL) : %RSD: | 99.3 98.3 99.0 98.4 99.5 99.0 99.0 0.37 | 99.3 99.1 99.3 99.1 98.8 98.9 99.1 0.21 | 99.1 98.9 99.3 99.1 98.8 98.8 99.0 0.22 | Level 1 (~25 µg/mL) : %RSD: | 100.0 100.2 100.0 99.8 99.6 99.4 99.8 0.28 | 99.7 100.0 99.8 100.2 102.0 100.5 100.4 0.85 | 100.3 101.2 100.7 100.7 100.5 101.0 100.7 0.32 | |

| Level 2 (~250 µg/mL) : %RSD: | 101.0 101.1 100.9 101.0 100.9 100.9 101.0 0.12 | 101.3 101.0 100.7 100.3 100.5 100.6 100.7 0.36 | 98.8 98.7 99.2 99.5 99.4 99.4 99.2 0.36 | Level 2 (~250 µg/mL) : %RSD: | 100.7 100.8 100.6 100.5 100.7 100.4 100.6 0.14 | 99.8 100.3 99.6 100.1 99.8 100.2 100.0 0.26 | 100.4 101.2 101.7 101.6 100.9 101.3 101.2 0.48 | |

| Level 3 (~500 µg/mL) : %RSD: | 100.3 100.7 100.9 100.6 101.1 101.2 100.8 0.33 | 100.8 100.9 101.2 100.7 100.7 100.9 100.9 0.19 | 99.1 99.3 99.5 99.4 99.3 99.4 99.3 0.16 | Level 3 (~500 µg/mL) : %RSD: | 98.6 99.9 100.1 99.7 99.8 99.5 99.6 0.53 | 98.2 98.8 98.3 98.6 98.8 98.8 98.6 0.26 | 99.1 98.8 98.7 98.5 99.0 99.0 98.8 0.24 | |

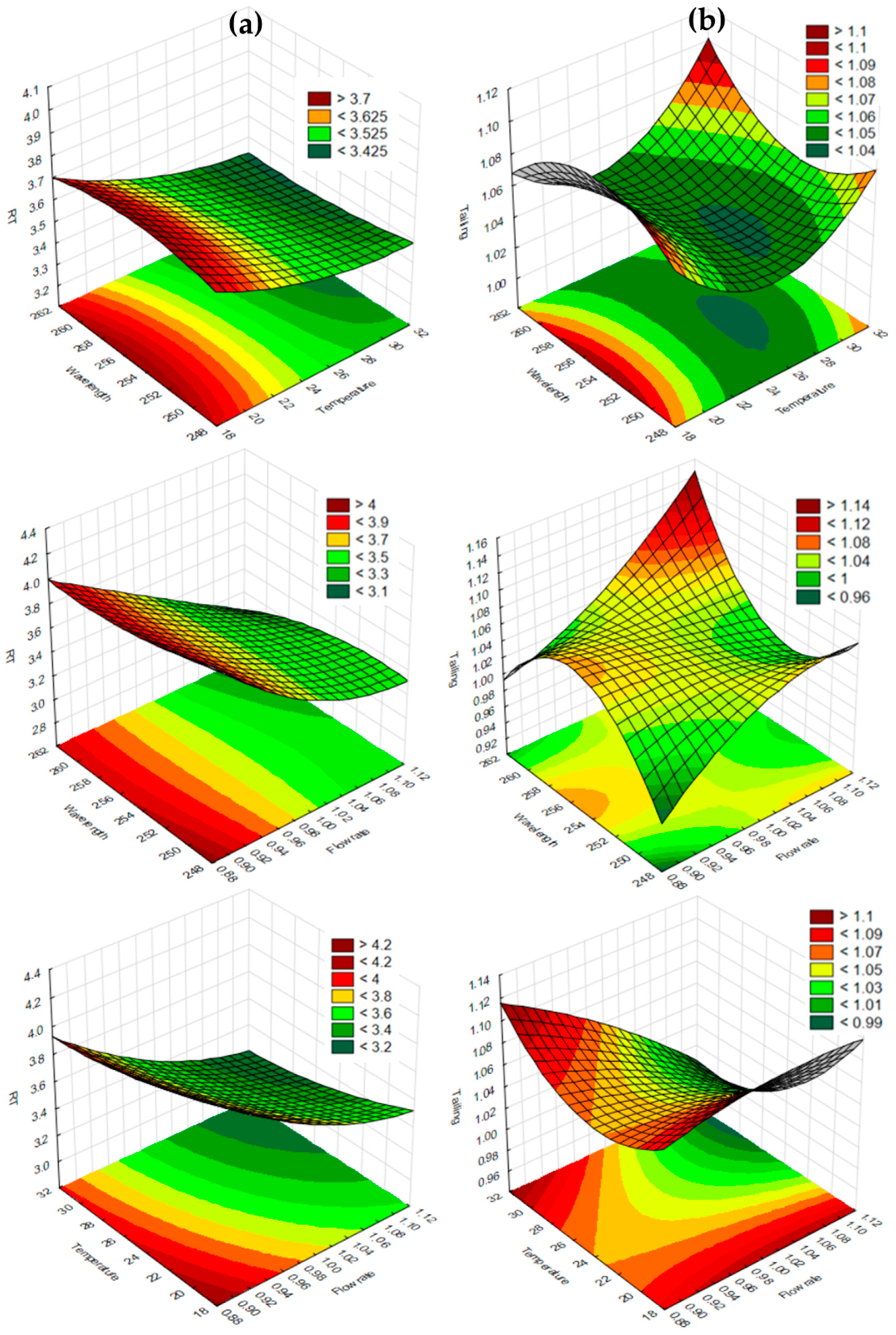

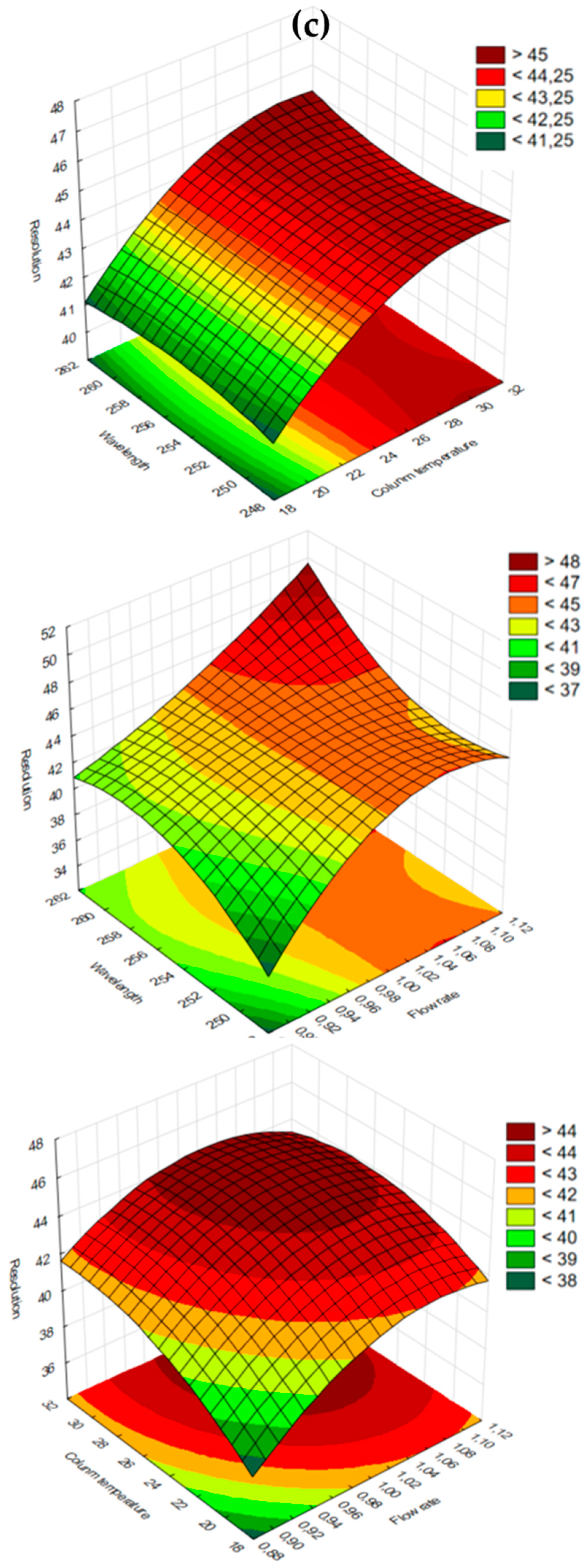

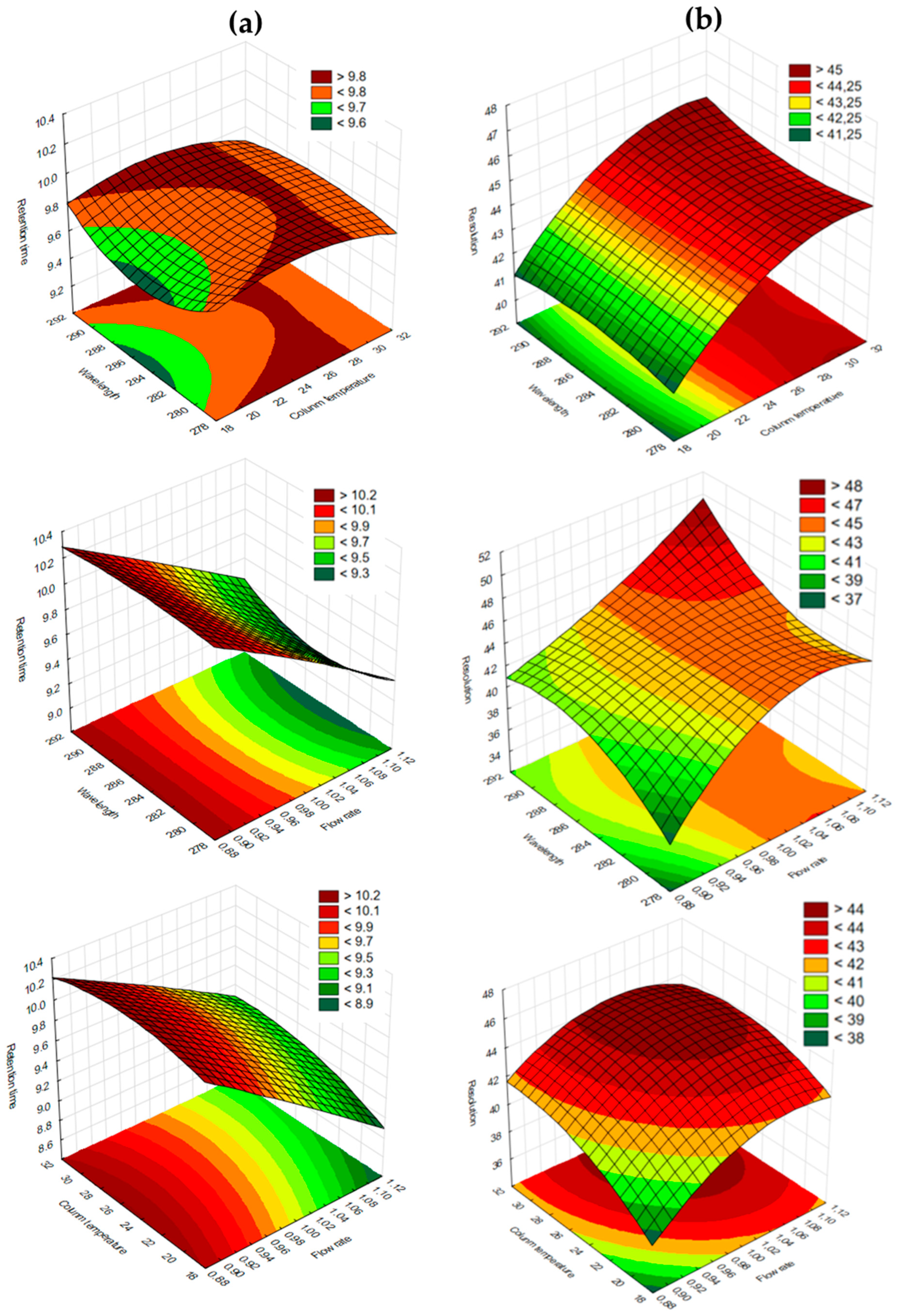

4.3. Robustness of the Method—A Box–Behnken Experimental Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIDS | Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| Adj. r2 | Adjusted correlation coefficient |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| AQbD | Analytical Quality-by-Design |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BBD | Box–Behnken Design |

| CFZ | Clofazimine |

| r2 | Correlation coefficient |

| CTB | Cutaneous Tuberculosis |

| EUC | Eucalyptus oil |

| EPTB | Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis |

| FDC | Fixed-Dose Drug Combination |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practice |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| ICH | International Council for Harmonization |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantitation |

| OLV | Olive oil |

| PPO | Peppermint oil |

| PZA | Pyrazinamide |

| QbD | Quality-by-Design |

| %RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

| RS | Resolution |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| TR | Retention Time |

| TF | Tailing Factor |

| TTO | Tea tree oil |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| USP | United States Pharmacopoeia |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Rullán, J.; Seijo-Montes, R.E.; Vaillant, A.; Sánchez, N.P. Cutaneous manifestations of pulmonary disease. In Atlas of Dermatology in Internal Medicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gramminger, C.; Biedermann, T. Recognising cutaneous tuberculosis. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2025, 23, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Kaur, I.; Mehta, S.; Singal, A. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Part I: Pathogenesis, classification, and clinical features. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Operational Handbook on Tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment-Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis Treatment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Chen, Q.; Chen, W.; Hao, F. Cutaneous tuberculosis: A great imitator. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 37, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Muralidhar, S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: A twenty-year prospective study. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 1999, 3, 494–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, A.; Mahajan, R.; Ramesh, V. Drug-resistance and its impact on cutaneous tuberculosis. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2022, 13, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, F.G.; Gotuzzo, E. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin. Dermatol. 2007, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment-Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment, 2022 Update; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- DOH. National Guidelines on the Treatment of Tuberculosis Infection; National Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2023. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/elibrary/national-guidelines-treatment-tuberculosis-infection (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Pradipta, I.S.; Houtsma, D.; van Boven, J.F.M.; Alffenaar, J.C.; Hak, E. Interventions to improve medication adherence in tuberculosis patients: A systematic review of randomized controlled studies. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2020, 30, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapfumaneyi, P.; Imran, M.; Mohammed, Y.; Roberts, M.S. Recent advances and future prospective of topical and transdermal delivery systems. Front. Drug Deliv. 2022, 2, 957732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunter, D.; Klang, V.; Eichner, A.; Savic, S.M.; Savic, S.; Lian, G.; Erdő, F. Progress in Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery Research-Focus on Nanoformulations. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godman, B.; McCabe, H.; Leong, T.D.; Mueller, D.; Martin, A.P.; Hoxha, I.; Mwita, J.C.; Rwegerera, G.M.; Massele, A.; de Oliveira Costa, J. Fixed dose drug combinations—Are they pharmacoeconomically sound? Findings and implications especially for lower- and middle-income countries. Expert. Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020, 20, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, M.; Gopinath, D.; Kalra, S. Triple fixed drug combinations in type 2 diabetes. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 19, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.; Chesov, D.; Heyckendorf, J. Clofazimine for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, N.C.; Swanson, R.V.; Bautista, E.M.; Almeida, D.V.; Saini, V.; Omansen, T.F.; Guo, H.; Chang, Y.S.; Li, S.Y.; Tapley, A.; et al. Impact of Clofazimine Dosing on Treatment Shortening of the First-Line Regimen in a Mouse Model of Tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheda, K.; Chang, K.C.; Guglielmetti, L.; Furin, J.; Schaaf, H.S.; Chesov, D.; Esmail, A.; Lange, C. Clinical management of adults and children with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Pang, Y.; Jing, W.; Liu, P.; Wu, T.; Cai, C.; Shi, J.; Qin, Z.; et al. Clofazimine improves clinical outcomes in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, Y.; Chen, H.; Xie, L.; Gao, M.; Ma, L.; Huang, Y. Retrospective Analysis of 28 Cases of Tuberculosis in Pregnant Women in China. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.; Brigden, G.; Cox, H.; Shubber, Z.; Cooke, G.; Ford, N. Outcomes of clofazimine for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagannath, C.; Reddy, M.V.; Kailasam, S.; O’Sullivan, J.F.; Gangadharam, P.R. Chemotherapeutic activity of clofazimine and its analogues against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In vitro, intracellular, and in vivo studies. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 151, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagracia, A.R.; Ong, H.L.; Lagua, F.M.; Alea, G. Chemical reactivity and bioactivity properties of pyrazinamide analogs of acetylsalicylic acid and salicylic acid using conceptual density functional theory. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Staden, D.; Haynes, R.K.; Viljoen, J.M. Adapting Clofazimine for Treatment of Cutaneous Tuberculosis by Using Self-Double-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, W.J.; Glass, D.; Goode, K.; Stables, G.I.; Boorman, G.C. A double-blind investigation of the potential systemic absorption of isotretinoin, when combined with chemical sunscreens, following topical application to patients with widespread acne of the face and trunk. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2001, 81, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Staden, D.; du Plessis, J.; Viljoen, J. Development of a Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System for Optimized Topical Delivery of Clofazimine. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Dressman, J.B.; Amidon, G.L.; Junginger, H.E.; Kopp, S.; Midha, K.K.; Shah, V.P.; Stavchansky, S.; Barends, D.M. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Isoniazid. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.E.; Elasala, G.S.; Mohamed, E.A.; Kolkaila, S.A. Spectral, thermal studies and biological activity of pyrazinamide complexes. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, E.A.; Dillon, N.A.; Baughn, A.D. The Bewildering Antitubercular Action of Pyrazinamide. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2020, 84, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, J.; McManus, S.A.; Lu, H.D.; Ristroph, K.D.; Cho, E.J.; Dobrijevic, E.L.; Chan, H.-K.; Prud’homme, R.K. Design and Solidification of Fast-Releasing Clofazimine Nanoparticles for Treatment of Cryptosporidiosis. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laudouze, J.; Rokitskaya, T.I.; Abolet, A.; Point, V.; Firsov, A.M.; Khailova, L.S.; Cavalier, J.F.; Canaan, S.; Baulard, A.R.; Antonenko, Y.N.; et al. Pyrazinamide kills Mycobacterium tuberculosis via pH-driven weak-acid permeation and cytosolic acidification. bioRxiv 2025. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ge, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Cui, D.; Yuan, G.; Wang, K.; Zhang, W. Influence of Surfactant and Weak-Alkali Concentrations on the Stability of O/W Emulsion in an Alkali-Surfactant-Polymer Compound System. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 5001–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramappa, V.; Aithal, G.P. Hepatotoxicity Related to Anti-tuberculosis Drugs: Mechanisms and Management. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2013, 3, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokania, S.; Joshi, A.K. Self-microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS)—Challenges and road ahead. Drug Deliv. 2015, 22, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauss, T.; Gaubert, A.; Tabaran, L.; Tonelli, G.; Phoeung, T.; Langlois, M.H.; White, N.; Cartwright, A.; Gomes, M.; Gaudin, K. Development of rectal self-emulsifying suspension of a moisture-labile water-soluble drug. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 536, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazi, M.; Al-Swairi, M.; Ahmad, A.; Raish, M.; Alanazi, F.K.; Badran, M.M.; Khan, A.A.; Alanazi, A.M.; Hussain, M.D. Evaluation of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems (SNEDDS) for poorly water-soluble talinolol: Preparation, in vitro and in vivo assessment. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrer, J.; Zupančič, O.; Hetenyi, G.; Kurpiers, M.; Bernkop-Schnuerch, A. Design and evaluation of SEDDS exhibiting high emulsifying properties. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 44, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgen, M.; Saxena, A.; Chen, X.Q.; Miller, W.; Nkansah, R.; Goodwin, A.; Cape, J.; Haskell, R.; Su, C.; Gudmundsson, O.; et al. Lipophilic salts of poorly soluble compounds to enable high-dose lipidic SEDDS formulations in drug discovery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 117, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, Q.D.; Wu, Y.M.; Liu, P.; Yao, J.H.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Duan, J.A. Potential of Essential Oils as Penetration Enhancers for Transdermal Administration of Ibuprofen to Treat Dysmenorrhoea. Molecules 2015, 20, 18219–18236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetta, T.P.; Simões, S.; Araújo, M.M.; Carvalho, T.; Arruda, C.; Marcato, P.D. Development of nanoparticles from natural lipids for topical delivery of thymol: Investigation of its anti-inflammatory properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 164, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staden, D.V.; Haynes, R.K.; Van der Kooy, F.; Viljoen, J.M. Development of a HPLC Method for Analysis of a Combination of Clofazimine, Isoniazid, Pyrazinamide, and Rifampicin Incorporated into a Dermal Self-Double-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System. Methods Protoc. 2023, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.J.Z.; Capen, R.C.; Schofield, T.L. Assessing the Reproducibility of an Analytical Method. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2006, 44, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICH. Validation of Analytical Procedures Q2(R2); U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_Q2-R2_Document_Step2_Guideline_2022_0324.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- United States Pharmacopoeia (USP). Chromatography. 2025. Available online: https://online.uspnf.com/uspnf/document/1_GUID-6C3DF8B8-D12E-4253-A0E7-6855670CDB7B_9_en-US#C621S12 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Patel, K.; Shah, U.A.; Patel, C.N. Box–Behnken design-assisted optimization of RP-HPLC method for the estimation of evogliptin tartrate by analytical quality by design. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppy, N.V.V.D.P.; Haridasyam, S.B.; Vadagam, N.; Sara, N.; Sara, K.; Tamma, E. Stability-indicating HPLC method optimization using quality by design with design of experiments approach for quantitative estimation of organic related impurities of Doripenem in pharmaceutical formulations. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 15, 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Tomić, J.; Djajić, N.; Agbaba, D.; Otašević, B.; Malenović, A.; Protić, A. Robust optimization of gradient RP HPLC method for simultaneous determination of ivabradine and its eleven related substances by AQbD approach. Acta Chromatogr. 2021, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Muddassir, M.; Alarifi, A.; Ansari, M.T. Box-Behnken Assisted Validation and Optimization of an RP-HPLC Method for Simultaneous Determination of Domperidone and Lansoprazole. Separations 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.W.; Boyes, B.E. Modern Trends and Best Practices in Mobile-Phase Selection in Reversed-Phase Chromatography. LCGC N. Am. 2018, 36, 752–767. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, M.J. The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals, 14th ed.; Merck: Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi, S.D.; Jacob, J.T. Validated Degradation studies for the estimation of Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol, Isoniazid and Rifampacin in a fixed dose combination by UPLC. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2018, 11, 2869–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, T.S.; Deshpande, A.S. Development of an Innovative Quality by Design (QbD) Based Stability-Indicating HPLC Method and its Validation for Clofazimine from its Bulk and Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms. Chromatographia 2019, 82, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, T. Essential Elements for a GMP Analytical Chemistry Department; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 195. [Google Scholar]

- LCGCs Chomacademy. HPLC Gradient Elution—Baseline Drift. Available online: https://www.chromatographyonline.com/view/hplc-gradient-elution-baseline-drift (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- van Deemter, J.J.; Zuiderweg, F.J.; Klinkenberg, A. Longitudinal diffusion and resistance to mass transfer as causes of nonideality in chromatography. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1956, 5, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, L.G.; Castells, C.B.; Ràfols, C.; Rosés, M.; Bosch, E. Effect of temperature on the chromatographic retention of ionizable compounds. II. Acetonitrile-water mobile phases. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1077, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, L.R.; Kirklank, J.J. Introduction to Modern Liquid Chromatography, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Interscience Publication, John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1979; p. 862. [Google Scholar]

| Time (Minutes) | Mobile Phase A (% v/v) | Mobile Phase B (% v/v) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | 93.0–90.0 | 7.0–10.0 | Linear gradient |

| 4–6 | 90.0–50.0 | 10.0–50.0 | Linear gradient |

| 6–10 | 50.0 | 50.0 | Isocratic |

| 10–12 | 50.0–93.0 | 50.0–7.0 | Linear gradient |

| 12–15 | 93.0 | 7.0 | Re-equilibration |

| Independent Variable | Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | |

| x1 Wavelength for PZA (nm) | 250 | 255 | 260 |

| Wavelength for CFZ (nm) | 280 | 285 | 290 |

| x2 Flow rate (mL/min) | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.10 |

| x3 Column temperature (°C) | 20 | 25 | 30 |

| Stress Conditions | Treatment of Samples | % Degradation Observed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PZA | CFZ | ||

| Acid degradation | 0.1 N HCl for 3 h at 60 °C | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Base degradation | 0.1 N NaOH for 3 h at 60 °C | 26.7 | 95.2 |

| Oxidation | 3% H2O2 for 3 h at 60 °C | 0.0 | 82.8 |

| PZA | CFZ | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run No. | Wave Length (nm) | Flow Rate (mL/min) | Column Temperature (°C) | RT (min) | TF | RS | Run No. | Wave Length (nm) | Flow Rate (mL/min) | Column Temperature (°C) | RT (min) | TF | RS |

| 1 | 250 | 0.9 | 25 | 4.00 | 1.0 | 40 | 1 | 280 | 0.9 | 25 | 10.23 | 1.2 | 40 |

| 2 | 260 | 0.9 | 25 | 3.90 | 1.0 | 42 | 2 | 290 | 0.9 | 25 | 10.23 | 1.1 | 42 |

| 3 | 250 | 1.1 | 25 | 3.33 | 1.0 | 44 | 3 | 280 | 1.1 | 25 | 9.37 | 1.1 | 44 |

| 4 | 260 | 1.1 | 25 | 3.19 | 1.1 | 47 | 4 | 290 | 1.1 | 25 | 9.41 | 1.1 | 47 |

| 5 | 250 | 1.0 | 20 | 3.66 | 1.1 | 42 | 5 | 280 | 1.0 | 20 | 9.73 | 1.2 | 42 |

| 6 | 260 | 1.0 | 20 | 3.65 | 1.1 | 42 | 6 | 290 | 1.0 | 20 | 9.74 | 1.1 | 42 |

| 7 | 250 | 1.0 | 30 | 3.47 | 1.1 | 45 | 7 | 280 | 1.0 | 30 | 9.78 | 1.1 | 45 |

| 8 | 260 | 1.0 | 30 | 3.44 | 1.1 | 45 | 8 | 290 | 1.0 | 30 | 9.78 | 1.1 | 45 |

| 9 | 255 | 0.9 | 20 | 4.06 | 1.1 | 40 | 9 | 285 | 0.9 | 20 | 10.15 | 1.1 | 40 |

| 10 | 255 | 1.1 | 20 | 3.46 | 1.1 | 43 | 10 | 285 | 1.1 | 20 | 9.11 | 1.1 | 43 |

| 11 | 255 | 0.9 | 30 | 3.83 | 1.1 | 43 | 11 | 285 | 0.9 | 30 | 10.20 | 1.2 | 43 |

| 12 | 255 | 1.1 | 30 | 3.22 | 1.0 | 44 | 12 | 285 | 1.1 | 30 | 9.37 | 1.1 | 44 |

| 13 | 255 | 1.0 | 25 | 3.54 | 1.0 | 44 | 13 | 285 | 1.0 | 25 | 9.79 | 1.1 | 44 |

| 14 | 255 | 1.0 | 25 | 3.53 | 1.1 | 45 | 14 | 285 | 1.0 | 25 | 9.78 | 1.1 | 45 |

| 15 | 255 | 1.0 | 25 | 3.53 | 1.0 | 44 | 15 | 285 | 1.0 | 25 | 9.78 | 1.2 | 44 |

| 16 | 255 | 1.0 | 25 | 3.53 | 1.0 | 44 | 16 | 285 | 1.0 | 25 | 9.76 | 1.2 | 44 |

| Average: | 3.58 | 1.05 | 43 | Average: | 9.76 | 1.1 | 43 | ||||||

| Standard deviation: | 0.26 | 0.02 | 1.87 | Standard deviation: | 0.33 | 0.03 | 1.87 | ||||||

| Relative standard deviation (%): | 7.13 | 2.38 | 4.3 | Relative standard deviation (%): | 3.37 | 3.00 | 4.3 | ||||||

| Dependent Variable | r2 Value | Adjusted r2 Value |

|---|---|---|

| RT of PZA | 0.99995 | 0.99975 |

| TF of PZA | 0.95008 | 0.75404 |

| RS of PZA and CFZ | 0.9921 | 0.97700 |

| RT of CFZ | 0.99976 | 0.99879 |

| TF of CFZ | 0.69829 * | 0.00000 * |

| RS of PZA and CFZ | 0.9954 | 0.97700 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brits, M.; Bouwer, F.; Viljoen, J.M. RP-DAD-HPLC Method for Quantitative Analysis of Clofazimine and Pyrazinamide for Inclusion in Fixed-Dose Combination Topical Drug Delivery System. Methods Protoc. 2026, 9, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010016

Brits M, Bouwer F, Viljoen JM. RP-DAD-HPLC Method for Quantitative Analysis of Clofazimine and Pyrazinamide for Inclusion in Fixed-Dose Combination Topical Drug Delivery System. Methods and Protocols. 2026; 9(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrits, Marius, Francelle Bouwer, and Joe M. Viljoen. 2026. "RP-DAD-HPLC Method for Quantitative Analysis of Clofazimine and Pyrazinamide for Inclusion in Fixed-Dose Combination Topical Drug Delivery System" Methods and Protocols 9, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010016

APA StyleBrits, M., Bouwer, F., & Viljoen, J. M. (2026). RP-DAD-HPLC Method for Quantitative Analysis of Clofazimine and Pyrazinamide for Inclusion in Fixed-Dose Combination Topical Drug Delivery System. Methods and Protocols, 9(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010016