1. Introduction

The European arrival in the Americas is often regarded as a symbolic marker of the onset of the Modern Age. Yet, by the final decades of the sixteenth century—when the colonisation of vast territories had already been firmly established—modern intellectual paradigms were still in their formative stages. The key figures of modern rationalism had not yet come to prominence: Francis Bacon and Galileo Galilei were still adolescents, and René Descartes had only just been born. This chronological disjunction suggests that, although colonial expansion was driven by ideological and theological constructs rooted in medieval Europe, the early phases of urban development in the Americas already displayed characteristics of a modern outlook that had only begun to take shape in Europe.

This interplay between inherited medieval frameworks and emergent modernity is especially apparent in urban design. The case of the City of Mexico—constructed atop the ruins of the Mexica capital, Mexico-Tenochtitlan—offers a particularly illuminating example. In this article, the term

City of Mexico is preferred over

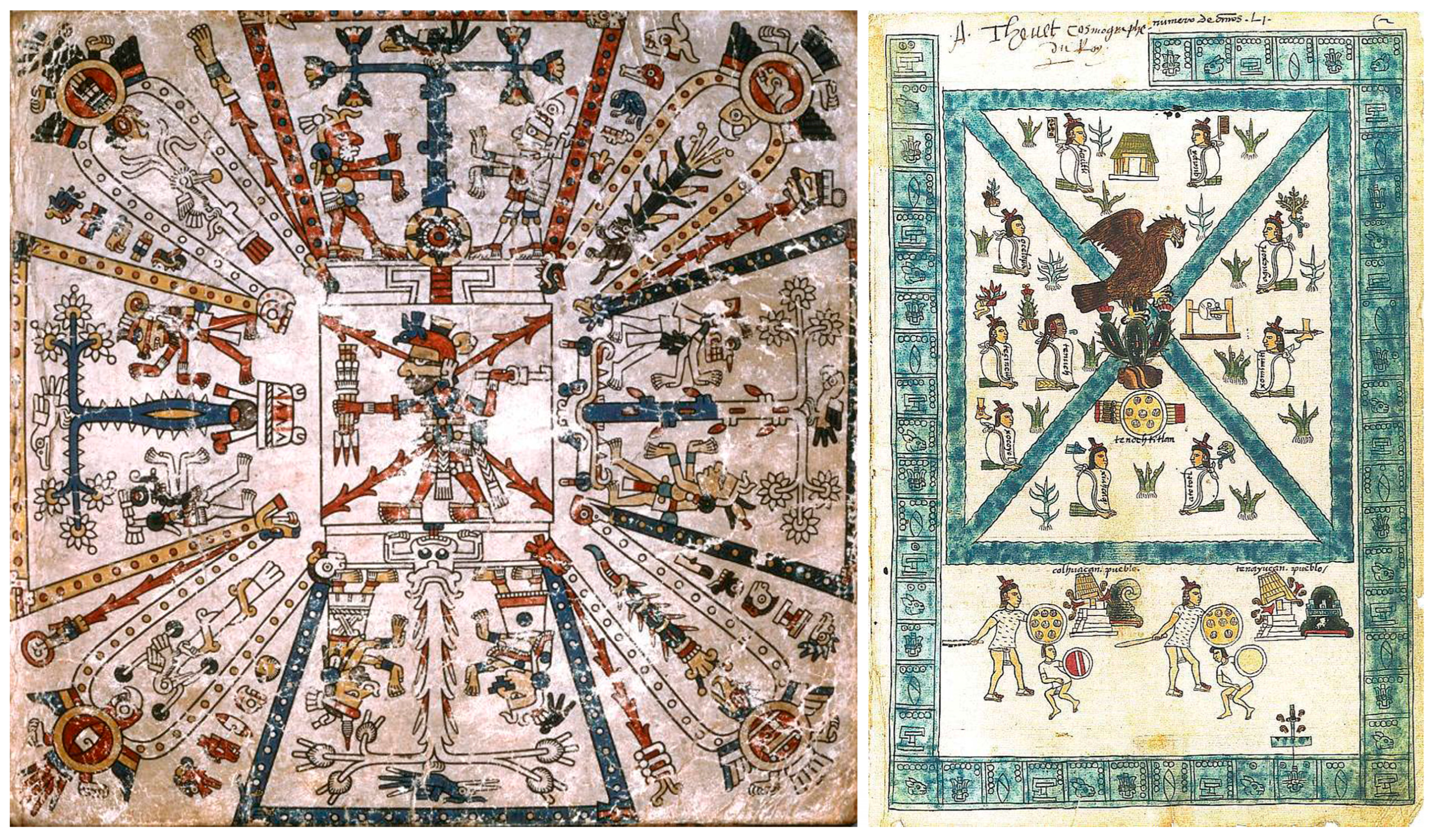

Mexico City to reflect the historical and institutional context of the sixteenth-century urban foundation established by the Spanish following the conquest of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. This terminology corresponds with contemporary colonial usage and underscores the distinction between the early viceregal capital and the modern metropolis. Rather than representing a straightforward imposition of Castilian orthogonal planning onto a vacant landscape, the transformation of the viceregal capital entailed a complex and evolving negotiation between European urban ideals and indigenous spatial systems. The Mexica city was characterised by a meticulously organised and symbolically charged urban structure, aspects of which are vividly documented in Mesoamerican sources such as the Fejérváry-Mayer and Mendocino codices. These sources not only depict spatial configurations but also encode cosmological principles, social hierarchies, and politico-religious functions that continued to exert influence within the colonial urban context (

Figure 1).

Conventional historiography has often interpreted early American urbanism as a direct continuation of European precedents, tracing its lineage from classical antiquity—Greece and Rome—through medieval models, culminating in Iberian examples such as Santa Fe in Granada. This view promotes a Eurocentric and linear first line of diffusion of modern urbanism. However, more recent academic work has revealed a far more intricate and polycentric reality. Across the pre-Hispanic Americas, urban civilisations such as Teotihuacan (2nd–7th centuries CE) in central Mexico demonstrate highly sophisticated urban planning that developed independently of European influence—evidence of what might be termed an alternative modernity. This concept of modernity in urbanism is closely tied to the pursuit of order—both spatial and symbolic—as cities were conceived not merely as physical spaces but as ordered frameworks reflecting cosmological principles, social hierarchies, and governance structures.

At the same time, within the Iberian Peninsula itself, a

second line of diffusion illustrates that Spanish urbanism evolved through diverse influences. A notable example is the city of Jaca in northern Spain, which adopted an orthogonal grid as early as the 11th century, guided by local charters that promoted egalitarian land distribution under the principle of ‘equal plots for equal men.’ These experiences, alongside theological and legal reflections on urban life—particularly through concepts such as policía and república (public order and polity)—were instrumental in shaping Spanish colonial urban ideals.

Antonio de Nebrija (

1495) defined

policía not merely as urban order but as encompassing civic life and moral conduct, a notion rooted in Ancient Greek political thought and further developed by medieval thinkers like Isidore of Seville, Alfonso X, and Francesc Eiximenis. For Spanish colonisers, especially in the aftermath of conquest, policía became a civilising tool: the establishment of towns where indigenous populations would reside ‘

en buena traza y policía’ (with well-structured urban form and civic governance), thus reflecting a modernising vision in which urban order was integral to the exercise of colonial authority and the imposition of a Christian republic (

Figure 2).

Nonetheless, the specific conditions of the American territories—including vast and varied geographies, local material constraints, and the persistence of indigenous settlements—necessitated the adaptation of royal ordinances in practice. The conquerors and the jumétricos (surveyors or planners) played a pivotal role in this process, mediating between idealised models and the practical challenges of spatial implementation. Consequently, early colonial cities in the Americas should not be regarded as mere replicas of a fixed template, but rather as negotiated outcomes shaped by multiple urban traditions.

Contemporary academic debates regarding the origins of the colonial grid in Spanish America generally fall into five principal categories:

Spontaneous Rational Urban Response: Some scholars contend that the grid emerged as a pragmatic and intuitive solution for rapidly organising new settlements.

Influence of the Italian Renaissance: Others argue that revived classical urban theories from the Italian Renaissance influenced colonial planning, although the radial designs favoured in these theories contrast with the rectilinear colonial grid.

Persistence of Indigenous Urban Traditions: A growing body of research underscores the continuity of pre-Hispanic urban forms, particularly in major centres such as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, which provided both physical templates and ideological foundations.

Extension of Spanish Urban Practices: This view interprets the colonial grid as a continuation of long-standing Iberian urban traditions, implemented in the Americas under royal mandates.

Fusion of Iberian and Indigenous Urban Models: Increasingly accepted, this interpretation regards colonial cities—especially the City of Mexico—as the product of a dynamic synthesis between European and indigenous planning traditions.

This article aligns with the fifth perspective. It aims to investigate how the urban structure of Mexico-Tenochtitlan informed the development of the colonial City of Mexico, challenging simplistic narratives of unilateral European imposition. Instead, it presents the city as a paradigmatic case of hybrid urbanism. Through an analysis of spatial continuities, symbolic reinterpretations, and planning methodologies, the study offers a more nuanced understanding of urban formation in Spanish America—one that recognises the enduring legacy of indigenous urbanism within the colonial project.

2. Materials and Methods

This investigation employs a multidisciplinary historical-analytical framework to examine the development of urbanism in early Spanish America, with particular emphasis on the interplay and continuity between pre-Hispanic urban configurations and colonial planning methodologies in Mexico-Tenochtitlan and the City of Mexico. The research integrates documentary, archaeological, and visual sources within a case study structure to provide a holistic perspective.

Extensive Documentary Analysis. The study draws on a broad range of primary sources, including the Laws of the Indies, royal decrees, colonial chronicles, and historical cartography—most notably the Uppsala Map and various plans preserved in archival collections. Administrative records detailing the division and governance of urban space are also examined. Furthermore, normative and ideological texts from the period are analysed to clarify Spanish notions of policía and urban order. These documentary sources are complemented by contemporary secondary scholarship, particularly archaeological and anthropological research on Tenochtitlan, which offer valuable insights into the material and social dimensions of the pre-Hispanic city. Contributions from urban historians and anthropologists regarding cultural interactions within the colonial urban context are likewise incorporated.

Multilayered Comparative Framework. A systematic comparison is conducted between the spatial, symbolic, and functional attributes of pre-Hispanic and Iberian urban models. This analysis transcends a purely geometric evaluation of orthogonal grids, encompassing symbolic interpretations—such as the sanctity of space, the significance of water, and the organisation of communication routes—alongside the socio-political practices embedded within each tradition. This comparative lens facilitates the identification of continuities, transformations, and discontinuities within the colonial urban landscape.

Targeted Case Study: Mexico-Tenochtitlan and the City of Mexico. Mexico-Tenochtitlan is selected as the central case study due to its historical prominence and the richness of available documentary and archaeological evidence. The research traces the evolution of the urban fabric from the original Mexica settlement to its reconfiguration as the viceregal capital, considering its social, political, and symbolic dimensions. Cartographic materials and textual documentation are scrutinised to evaluate the practical application of Spanish ordinances within the existing urban framework and the modifications introduced by the conquerors. Comparative references to other Ibero-American colonial cities founded upon indigenous settlements provide further contextual depth.

Taken together, these methodological components ensure a rigorous and nuanced approach that acknowledges the complexities of colonial urban formation. Rather than reinforcing reductive models of cultural imposition, the study foregrounds the dynamic and reciprocal engagement between indigenous and European urban traditions.

3. State of the Art

This analysis seeks to demonstrate that the emergence of modern urbanism—understood not as a fixed model but as an evolving process—would likely have required a considerably longer trajectory had it not been accelerated by the convergence between two distinct yet complementary urban traditions: that of the Mexica, rooted in Mesoamerican cosmology and spatial planning, and that of the Spanish, grounded in classical, medieval, and early modern European thought. This convergence materialised in a uniquely charged historical setting: Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Mexica Empire, founded in 1325 on an island in Lake Texcoco. The city’s structured network of canals, causeways, and ceremonial precincts, centred around the Templo Mayor, reflected a deeply symbolic urban logic. After its conquest and partial destruction in 1521, this sophisticated spatial framework was not erased but rather adapted as the foundation for the new viceregal capital, the City of Mexico.

In parallel to these historiographical inquiries,

Rojas (

2023) offers a critical perspective on the symbolic and ideological transformation of Tenochtitlan into the colonial and modern City of Mexico. While much of the scholarly debate has centered on the roles of Spanish actors and, more recently, indigenous agency in the city’s physical reconstruction and urban planning, Rojas shifts attention to the erasure and reinterpretation of Mexica spatial logics and meanings in the post-conquest city. He argues that the colonial project not only reshaped the built environment but also deliberately suppressed indigenous memory and presence in the urban fabric. This perspective invites us to read the city as a palimpsest—layered with silenced histories—where the traces of Tenochtitlan persist beneath successive overlays of colonial and nationalist narratives.

However, to fully understand the hybrid nature of urbanism that emerged in the City of Mexico, it is essential to contextualise it within the broader evolution of urban ideas and practices within the Iberian Peninsula during the medieval and early modern periods. This peninsular tradition formed a crucial intellectual and practical framework for Spanish colonial planning, even as it interacted dynamically with indigenous forms.

A distinct line of urban development emerged in Spain from the eleventh century onward. Early examples, such as the orthogonal plan of Jaca, reveal the influence of local fueros and egalitarian principles of land distribution (

Bielza de Ory 2002). The repopulation policies of Alfonso X in the thirteenth century led to the establishment of villas and pueblas—urban settlements often lacking formal plans, yet reflecting an emerging vision of spatial order and royal authority (

Valdeón Baruque 2003). In the Crown of Aragon, more regularised plans were implemented by monarchs such as James II of Majorca, whose ordinances promoted square-grid layouts that integrated urban and territorial planning (

Alomar Esteve 1976).

Theoretical contributions also played a significant role. Francesc Eiximenis, writing in the fourteenth century, envisioned the ideal city as a square, symmetrical space inspired by Christian cosmology—divided into four quadrants, centred on a civic plaza, and embodying divine harmony (

Antelo Iglesias 1985;

Cervera Vera 1989;

Vila 1984). Although his model was never built, it formed part of a broader scholastic tradition that sought to link urban form with moral and theological order.

Despite these innovations, the orthogonal city remained the exception rather than the rule in late medieval Spain. Even Seville—the principal port of departure for the Indies and an administrative hub—retained a medieval urban structure, with narrow, winding streets, irregular blocks, and a layout inherited in part from its Islamic past (

Moya-Olmedo and Núñez-González 2023). Early colonial expeditions, including those led by Columbus, Ovando, Pedrarias Dávila, and Velázquez de Cuéllar, departed from and had experience with cities that were still deeply shaped by these organic, medieval forms.

It is therefore striking that the orthogonal grid found its most consistent and systematic application not in the Iberian Peninsula but in the Americas. Scholars have long debated whether this was the result of Renaissance ideals, royal ordinances, or spontaneous colonial pragmatism (

García Zarza 1996;

López Guzmán 1997;

Sánchez de Carmona 1989). The case of Mexico, however, reveals that the ordered layout of the colonial city was not merely the projection of Spanish models onto an empty space, but rather the reconfiguration of a highly structured indigenous city. As such, the foundation of Mexico represents a turning point in the global history of urbanism: a fusion of two distinct but converging traditions—each with its own cosmological, spatial, and political logic.

Before turning to a more detailed analysis, it is therefore essential to consider how these parallel developments—Mesoamerican and Iberian—interacted, clashed, and ultimately synthesised in the unique case of the City of Mexico, forming a model that would influence urban planning throughout Spanish America.

4. Development and Analysis

4.1. Before Mexico-Tenochtitlan: Mesoamerican Urban Traditions

Mesoamerica developed a sophisticated urban tradition over several millennia prior to the Spanish arrival in the early sixteenth century. While thousands of archaeological sites—including extensive urban centres—attest to this complex urban heritage, detailed knowledge beyond physical excavations was historically limited, resulting in a wide spectrum of scholarly interpretations. For many years, Maya ceremonial centres were not considered true cities; they were frequently dismissed as purely ritual spaces lacking urban characteristics. However, the recent widespread application of LiDAR technology has revolutionised this understanding by revealing vast residential districts, agricultural landscapes, and even marketplaces within the interstitial areas of these centres. These discoveries have profoundly reshaped academic perspectives on Maya urbanism (

Auld-Thomas et al. 2024;

Chase et al. 2020).

Teotihuacan, a major urban centre of the Classic period, stands as a paradigmatic example of deliberate and sophisticated city planning. Its orthogonal grid, structured around the Calzada de los Muertos, is framed by monumental ceremonial complexes, including the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon and the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. Extending beyond this ritual core, apartment compounds and specialised craft workshops formed a dynamic civic environment, underscoring Teotihuacan’s sustained function as an urban entity of considerable complexity (

Matos Moctezuma 1994).

Contemporary scholarship, drawing on extensive data from the Teotihuacan Mapping Project TMP (

Millon et al. 1973), estimates the city’s population during the Xolalpan phase (c. 400–550 CE) at approximately 100,000 inhabitants. Research suggests that residential compounds housed multiple households and functioned as corporate neighbourhood units (

Smith et al. 2019). These modular arrangements appear to have provided the structural basis for a city-wide grid that endured for centuries, integrating hydraulic systems and thoroughfares aligned with both cosmological and ideological principles (

Smith et al. 2019;

Sugiyama et al. 2021).

Analyses of Teotihuacan’s apartment compounds reveal recurring architectural layouts, typically organised around central courtyards and shared facilities. The majority of residents appear to have belonged to a middle-status demographic, with higher-status compounds concentrated along the Calzada de los Muertos. The scale and configuration of these dwellings were integral to Teotihuacan’s modular planning and enabled the city to sustain an unusually high population density (

Smith et al. 2019).

Teotihuacan’s architectural and symbolic influence resonated throughout Mesoamerica. While its urban features were seldom reproduced wholesale, they were frequently adapted to local contexts. Elements such as triadic temple arrangements and cosmologically oriented city plans reinforced Teotihuacan’s stature as a multi-ethnic civic and religious centre with enduring ideological reach (

Figure 3).

Mesoamerican urbanism was shaped not merely by its physical architecture but was fundamentally rooted in cosmogonic worldviews. Cities were conceived as sacred centres—

axis mundi—that mirrored the structure of the universe and upheld cosmic equilibrium. The notion of

altepetl encompassed both political identity and sacred geography, functioning as a microcosm of the cosmos (

Fernández Christlieb and Urquijo Torres 2020;

Ramírez Ruiz 2024).

Tenochtitlan epitomised this principle. Founded on an island in Lake Texcoco and anchored in a mythologically rich origin narrative, the city was oriented around the

Templo Mayor, its ritual nucleus, and conceptualised as a cosmic axis linking the heavens, the earth, and the underworld (

Aveni et al. 1988;

Matos Moctezuma and López Luján 1993).

Recent geospatial studies lend further credence to this interpretation.

Baeza Guerra (

2025) demonstrates that the city’s location was deliberately selected with reference to sacred landscapes and astronomical alignments, reinforcing the perception of its divinely ordained foundation. Consequently, Tenochtitlan’s extensive urban and ceremonial infrastructure was legitimised not solely through political authority, but through its cosmological resonance as well (

Millán 2023).

4.2. Before Mexico-Tenochtitlan: Spanish Urban Ideals

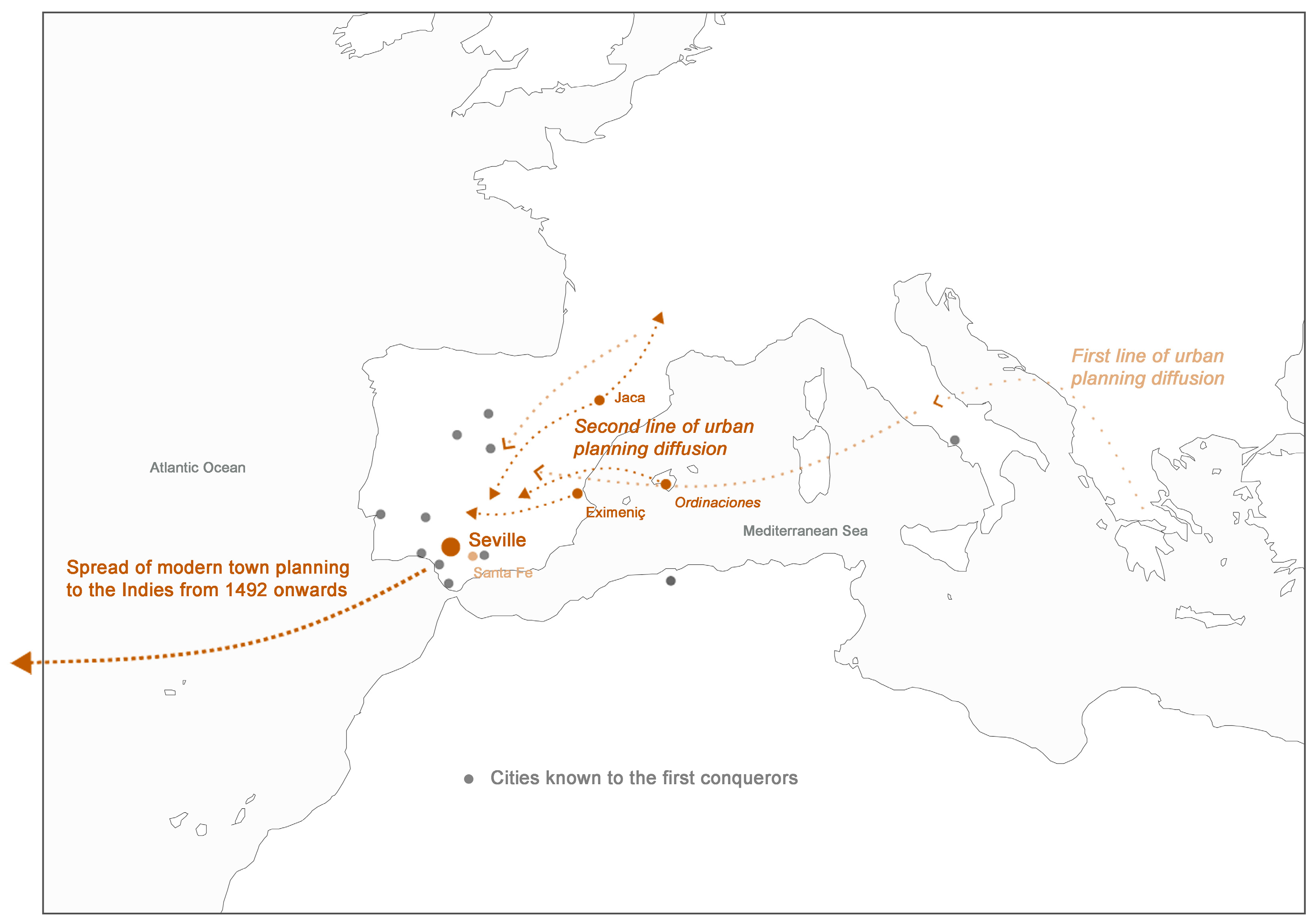

Historically, it has been widely accepted that the origins of modern urbanism, as it developed in the Americas from the sixteenth century onwards, were exclusively of European invention—representing one line of diffusion of modern urban planning. This interpretation rests on the assumption that urban modernity arose solely from Western traditions, beginning with ancient Greek civilisation and evolving through successive stages: from the Roman castrum, through the medieval bastides of France, and culminating in the foundation of Santa Fe near Granada at the close of the fifteenth century, under the Catholic Monarchs (

Bonet Correa 1991;

Esteras Martín et al. 1990;

Gutiérrez Dacosta 1984;

Hardoy 1975;

Morris 2018;

Palm 1951a;

Terán 1989) (

Figure 4).

However, it is important to emphasise that, as has been demonstrated, cities across the American continent—developed entirely independently of European traditions—exhibited highly structured and sophisticated urban layouts during this same historical period. These cases provide compelling evidence that advanced urban planning emerged autonomously in the Americas, representing an alternative line of diffusion of modern urbanism, distinct from the Western canon.

Moreover, while the aforementioned European developments are historically significant, certain precedents within the Iberian Peninsula can be recognised as key milestones in the invention and dissemination of modern urbanism. A particularly illustrative example is the adoption of the orthogonal layout in the 11th-century city of Jaca, in northern Spain. This innovation was linked to a local charter that promoted social equity through the principle of ‘equal plots for equal men’, and it played a formative role in shaping subsequent bastides and related urban foundations across the peninsula (

Bielza de Ory 2002).

Similarly, during the second half of the 13th century, a new phase of urban development emerged under the Crown of Castile. King Alfonso X the Wise launched a programme of repopulation through the foundation of

villas and

pueblas—also referred to as

polas—with the strategic objective of reinforcing royal authority over lands previously dominated by local lords. This initiative extended across the northern (Galicia, Asturias, the Basque Country), central, and southern (Castile and Andalusia) regions of the peninsula. Nevertheless, at this stage, these settlements generally lacked fully articulated or consistent urban layouts (

Valdeón Baruque 2003).

The emergence of a more regularised urban model occurred somewhat later under the Crown of Aragon, particularly through the initiatives of King James II of Majorca and the urban ordinances he promulgated during the 14th century (

Alomar Esteve 1976). Distinct from the traditional orthogonal layouts based on rectangular grids, the Aragonese model was structured around a square-based grid system, which extended beyond urban centres to encompass broader territorial planning. Early precedents for this approach can be identified in cities such as Teruel and Castellón, where increasingly coherent spatial orders were already beginning to take shape.

These innovations attracted the attention of contemporary thinkers. In the 14th century, the Franciscan friar Francesc Eiximenis, writing in Valencia, articulated a utopian vision of the ideal city: a square-shaped urban centre characterised by order and beauty, inspired by the celestial Jerusalem. This vision, expressed in the

Dotzè del Crestià, is regarded as one of the earliest formulations of urban theory predating the Renaissance. His conceptual plan was organised around orthogonal axes dividing the city into four quadrants, embodying the Gothic-Christian cosmology shaped by the thought of Thomas Aquinas and the scholastic tradition of the University of Paris. At its core lay a central square, functioning as both symbolic and civic nucleus. Although never realised in practice, Eiximenis’s model reflected a deep aspiration for an urban order that was not only rational and geometric but also morally grounded (

Antelo Iglesias 1985;

Cervera Vera 1989;

Vila 1984).

Taken together, the urban developments that emerged in the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon between the 11th and 14th centuries can be understood as a distinct peninsular line of urbanism. While connected to broader European traditions—particularly Roman and Christian ideals—these initiatives responded to specific historical and territorial conditions within the Iberian context (

Figure 5).

This vision aligns with broader European urban ideals, particularly those that gained prominence in Spain during the 15th and 16th centuries. These ideals were rooted in a synthesis of classical Roman theory, medieval military concerns, and Christian cosmological principles. In this framework, cities were conceived as material expressions of divine order and royal authority—paradigms of policía (civic order) and Christian rectitude. Urban form was to reflect centralised power, geometric clarity, defensive rationality, and aesthetic harmony.

Notably, the ideal of the orthogonal city was not widespread in pre-colonial Spain. Although some examples such as Santa Fe and Puerto Real adopted grid layouts, they remained limited in scale and consistency. The Roman castra, while theoretically influential, had often been obscured or distorted by the organic growth of medieval towns, rendering their original geometries practically unrecognisable by the time of the conquest of the Americas.

Figures such as Francesc Eiximenis, in his 14th-century Dotzè del Crestià, contributed to this intellectual tradition by proposing a utopian “Ideal City” structured on rigorous geometric principles—square in form, divided into quadrants, and centred around a civic plaza. His model embodied a theological and moral vision of urban life, linking spatial order with Christian ethics and scholastic reasoning.

Paradoxically, it was in the Americas—not in the Iberian Peninsula—that these theoretical ideals found their most systematic and consistent realisation. The New World offered a unique context for the large-scale implementation of orthogonal planning. Yet, interpreting this as solely a European imposition overlooks the existence of highly developed and autonomous urban traditions in the Americas. As demonstrated, Mesoamerican cities already exhibited complex spatial geometries, cosmological alignments, and civic structures, pointing to an independent—and no less sophisticated—trajectory of urban thought and practice.

4.3. Mexico-Tenochtitlan: The Imperial Metropolis

Founded in 1325 on a small island in Lake Texcoco, Tenochtitlan initially grew under the political dominance of Azcapotzalco. Its expansion remained limited until it gained independence and formed the Triple Alliance around 1430, marking the beginning of a period of rapid and large-scale development. By the early 16th century, the city had become one of the largest urban centres in the world, with population estimates ranging from 60,000 to over one million—surpassing even Teotihuacan at its height (

Bravo-Almazán 2022;

Matos Moctezuma 2006;

Mundy 2018).

This demographic growth was accompanied by increasing administrative complexity. The Triple Alliance established a system of governance that accounted for the diverse historical trajectories of conquest and alliance throughout the expanding empire. This framework enabled the consolidation of strong central authority while allowing for a degree of local administrative flexibility. The city’s sustainability depended on an extensive tribute network that ensured the continuous flow of resources to the capital. In this way, Tenochtitlan’s economic and political power were deeply intertwined, with its imperial structure and capital city reinforcing one another in a highly efficient system.

Early Spanish chroniclers expressed amazement at the scale, organisation, and infrastructure of the city. Hernán Cortés famously likened Tenochtitlan to Seville or Córdoba, noting its broad, straight thoroughfares—partly paved and partly canalised—intersected by sturdy bridges wide enough to accommodate mounted troops (

Cortés 1981). Similarly, Bernal Díaz del Castillo observed that even veterans of campaigns in Constantinople and Italy had never encountered a plaza of such symmetry and grandeur (

Díaz del Castillo 1939).

Built on an island in a saltwater lake, Tenochtitlan demanded exceptional engineering and a coherent urban vision. The transformation of its lacustrine setting into a structured and symbolically charged cultural landscape in less than two centuries demonstrates a sophisticated integration of hydraulic engineering, logistical planning, cosmological symbolism, and political authority (

Merlo Juárez 2022;

Rubial García and Ramírez Méndez 2023).

The city was divided into four principal

calpulli or districts—believed to have been ordained by the deity Huitzilopochtli—centred around a ceremonial precinct. This quadripartite configuration corresponded to the four cardinal directions, reflecting Aztec cosmology and ritual geography. The spatial order was reinforced by four major causeways connecting Tenochtitlan with Tepeyac (north), Tacuba (west), Iztapalapa (south), and a lesser route to the east, emphasising the city’s symbolic and strategic centrality (

Fernández Christlieb and Urquijo Torres 2020).

Tenochtitlan was thus more than a marvel of engineering; it was a deliberately constructed cosmogram, embodying a multi-layered system of religious, administrative, and geographical order. The city’s urban design reflected a vision of the cosmos central to Mexica political and spiritual ideology. Scholars have identified this layout as a manifestation of cosmic principles, encoded in both architecture and urban planning. Codices such as the Fejérváry-Mayer and Mendocino reveal a shared geometric and symbolic framework, exemplifying a long-standing Mesoamerican tradition of spatial and semiotic organisation (

Figure 6).

Tenochtitlan itself was conceived as the

axis mundi—or

xictli, the ‘navel of the world’—the pivotal point maintaining cosmic equilibrium. Cartographic reconstructions highlight diagonal alignments connecting sacred sites such as Tenayuca, Culhuacan, Tepeyacacan, and Coyohuacan, all converging on Tenochtitlan and its sister city, Tlatelolco. These intersections formed a sacred geometry that enclosed major ritual centres. The city’s precise astronomical orientation structured not only its ceremonial layout but also its economic functions, with the Tlatelolco marketplace serving as a cornerstone of the imperial tribute system (

Fernández Christlieb and Urquijo Torres 2020).

4.4. At the Same Time as Mexico-Tenochtitlan: Cities in the Iberian Peninsula

Understanding the development of urbanism in the Iberian Peninsula at the dawn of the Early Modern period requires acknowledging two fundamental elements inherited from medieval traditions: city walls and churches. These features defined the core of most urban settlements until more structured urban layouts began to emerge in the northeast of the Peninsula during the 11th century (

Gutiérrez Millán 2001).

Within a relatively short time, the consolidation of urban centres led to the creation of spaces and buildings that became key landmarks for future urban growth (

Moya-Olmedo and Núñez-González 2023).

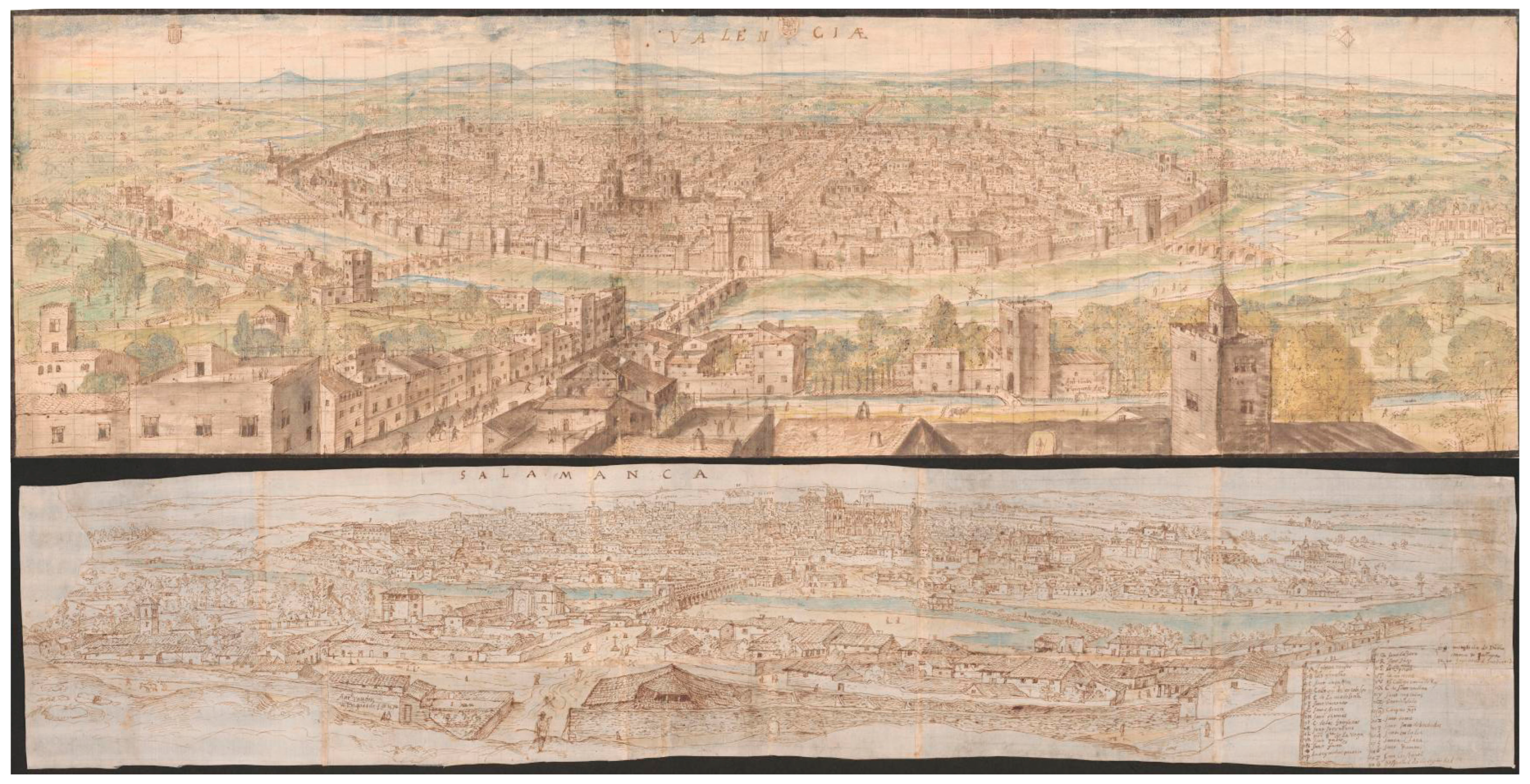

It is also important to note that the conquistadors and those tasked with founding the first cities in the newly acquired American territories were only familiar with urban centres still shaped by the medieval characteristics of the Iberian Peninsula. They had little or no exposure to the emerging urban innovations mentioned above. The list of such historical figures is extensive; however, by highlighting a few individuals and the cities they are known to have visited prior to their voyages to the Indies, this point may be clearly illustrated (

Figure 7).

Christopher Columbus visited several Portuguese cities, including Lisbon, as well as Spanish towns such as Palos de la Frontera, Cádiz, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda in southern Spain.

Nicolás de Ovando, Governor-General of the Indies, originated from Cáceres in western Spain and had ties to the Order of Alcántara in Extremadura, where he served as Grand Commander. He also maintained connections with the city of Cádiz.

Pedro Arias Dávila, known as Pedrarias Dávila and Governor of Castilla del Oro (mainland territories), was born in Segovia (central Spain). He was familiar with cities such as Granada and Sanlúcar de Barrameda in the south, as well as several cities in Algeria.

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, Governor of the island of Cuba, hailed from Cuéllar (near Segovia, central Spain), and had also visited Cádiz. Additionally, he had spent time in Naples, a significant city in its own right.

Hernán Cortés, Captain General and Chief Justice of the future New Spain, was born in Medellín (western Spain) and had contact with cities such as Salamanca and Valladolid (central Spain), Valencia (eastern Spain), and Granada (southern Spain).

All of these individuals passed through Seville during their travels. Following the establishment of the Casa de Contratación in 1503, Seville became the principal gateway to the Americas, centralising the administration and commerce of the newly acquired territories. However, like most Iberian cities of the time, Seville’s urban structure remained strongly influenced by its medieval legacy. The city was organised around its defensive walls and churches, which formed the focal points of its urban landscape. Buildings typically had narrow façades and extended deep into the plot, closely clustered around religious institutions, resulting in densely built neighbourhoods. In peripheral districts and suburbs, development was more scattered, concentrated around gates and roads, with increasing open spaces towards the outskirts (

Figure 8).

Furthermore, Seville’s historical evolution contributed to a highly irregular urban fabric, with a complex street network partially inherited from its Islamic past. The city’s layout cannot be regarded as modern or remotely orthogonal, as it lacked the geometric planning that would later come to characterise Spanish colonial urbanism (

Moya-Olmedo and Núñez-González 2023).

4.5. At the Same Time as Mexico-Tenochtitlan: Early Colonial Urbanization in the Americas

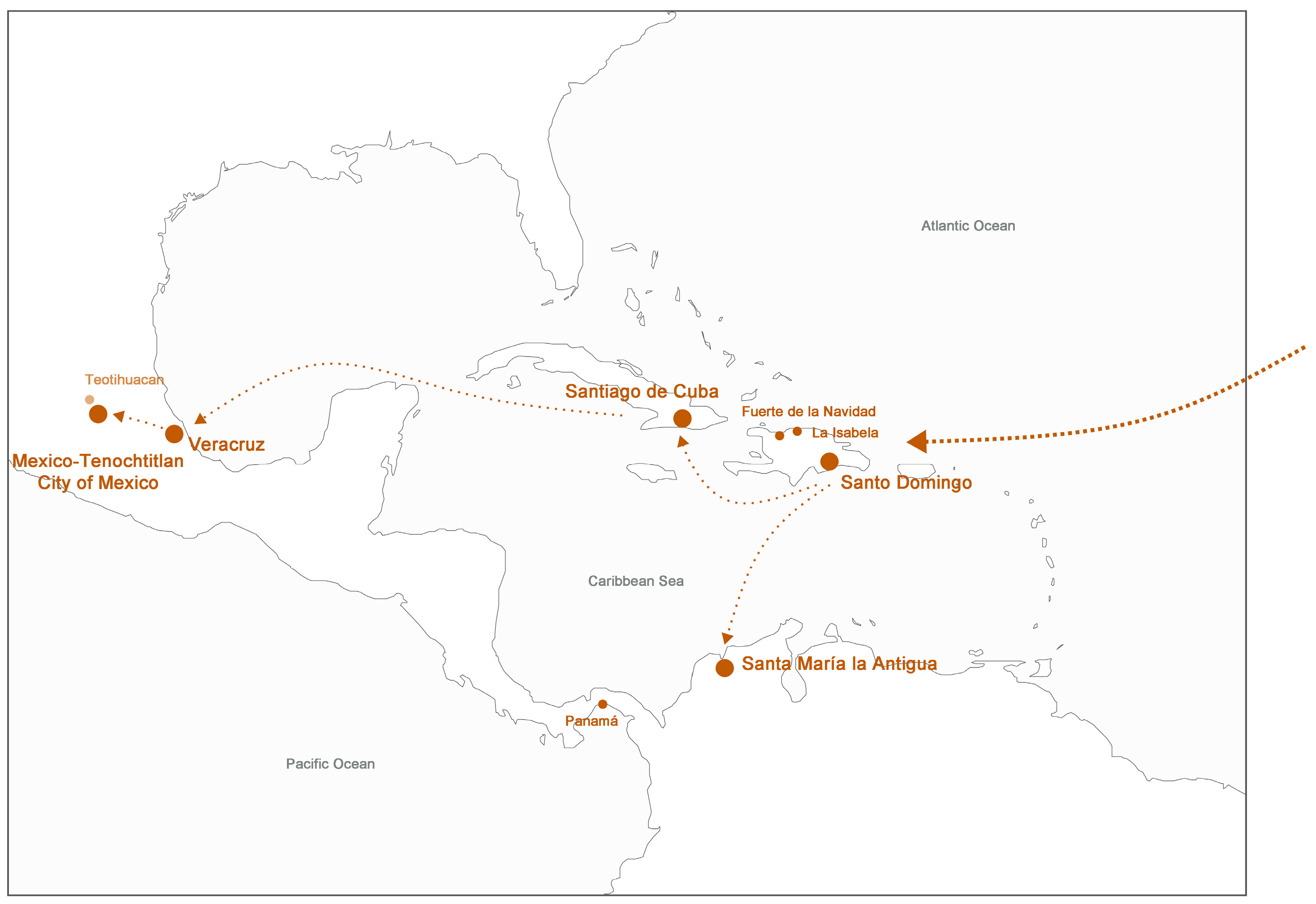

The earliest attempts to establish cities in the New World at the beginning of the 16th century lacked the defining features of modern urbanism. These initial settlements were temporary and spontaneous, rather than guided by the meticulously planned designs that would later characterise Spanish colonial cities. Their significance lay not in their internal organisation, but in their strategic function: asserting control over, and facilitating the population of, newly discovered territories on behalf of the Crown of Castile. The founding of these cities was often formalised through a ceremonial act and a legal framework derived from Iberian precedents (

Brewer-Carías 1998) (

Figure 9).

A notable example is found in the first settlements founded by Columbus on the island of Hispaniola. Due to a combination of geographical and economic challenges, these early colonies were ultimately abandoned in favour of more strategically advantageous locations. The earliest of these was Fort Navidad (1492–1493), where 39 men were left behind when Columbus returned to Spain. However, upon his return, the fort had been destroyed. La Isabela (1493–1498), also established on the island, represented the first attempt at a permanent colony. Nonetheless, it too was abandoned within a few years due to persistent difficulties.

Santo Domingo was founded by Columbus’s brother in the south of Hispaniola and became the first permanent city in the newly acquired territories, serving as the capital of the Viceroyalty of Hispaniola. It may be regarded as a successful foundation, although only four years later, in 1502, Governor Nicolás de Ovando ordered its relocation. Contemporary observers praised the apparent straightness of its streets, which were said to have been laid out “as if by string line.” However, closer analysis reveals that while the streets were indeed straight, they did not follow a strictly parallel arrangement. This resulted in the formation of polygonal blocks of varying sizes, adjoining a main square that was likewise polygonal and notably off-centre (

Lucena Giraldo 2006).

Although the layout fell short of the geometric precision of an orthogonal grid, it nevertheless represented a significant step forward. Despite its imperfections, the capital of the new territories—at least until the founding of the City of Mexico—was regarded by contemporaries as superior to many cities in the Iberian Peninsula, noted in particular for its level, wide, and straight streets. By the late 16th century, one could say that a relatively regular urban layout had taken shape, one that was clearly more advanced than traditional peninsular models. Cortés would later reside in Santo Domingo.

The establishment of other coastal cities—crucial for securing defence and logistical support during the expansion of the conquest—also marked a significant milestone in the evolution of urbanism. One notable example is Santa María la Antigua, the first major settlement on the mainland, founded in 1510. Its location was partly determined by the presence of a pre-existing indigenous settlement. However, following the arrival of Pedrarias Dávila in 1514, accompanied by over a thousand Castilian settlers, a process of expansion and reorganisation was initiated in accordance with directives issued by the Crown. By the end of 1515, Pedrarias officially declared that Santa María was a properly organised city (

Quintero Agámez and Sarcina 2021;

Tejeira Davis 1996).

Although no graphic representation of its urban layout has survived, it is plausible to assume that Santa María possessed a more irregular structure compared to the first foundation of Panama. The latter was laid out with an orthogonal plan, despite variations in block dimensions and street alignment. García Bravo resided in Santa María la Antigua.

Similarly, between late 1510 and early 1511, Velázquez de Cuéllar undertook an expedition to Cuba, where he established a network of urban settlements across the island. Within this framework, Santiago de Cuba—founded in 1515—was the last of the cities to be established in Cuba. Its location was chosen based on several criteria, including ease of communication, the availability of a suitable port, and strategic defensive advantages. However, the site was ultimately deemed unhealthy, leading to its eventual relocation (

Gavira Golpe 1983).

Although claims were made in the late 17th century that Santiago’s layout followed a grid pattern aligned with the cardinal directions, available evidence suggests that its urban plan was, in fact, irregular. Cortés served as Mayor of Santiago de Cuba.

Consequently, it cannot be concluded that the urban experiences familiar to Cortés in Santo Domingo and Cuba, or to García Bravo on the mainland, served as direct models for the layout of the new cities established in the territory later known as New Spain. These earlier settlements were not characterised by orthogonality or by systematic planning in the modern sense of urbanism (

Figure 10).

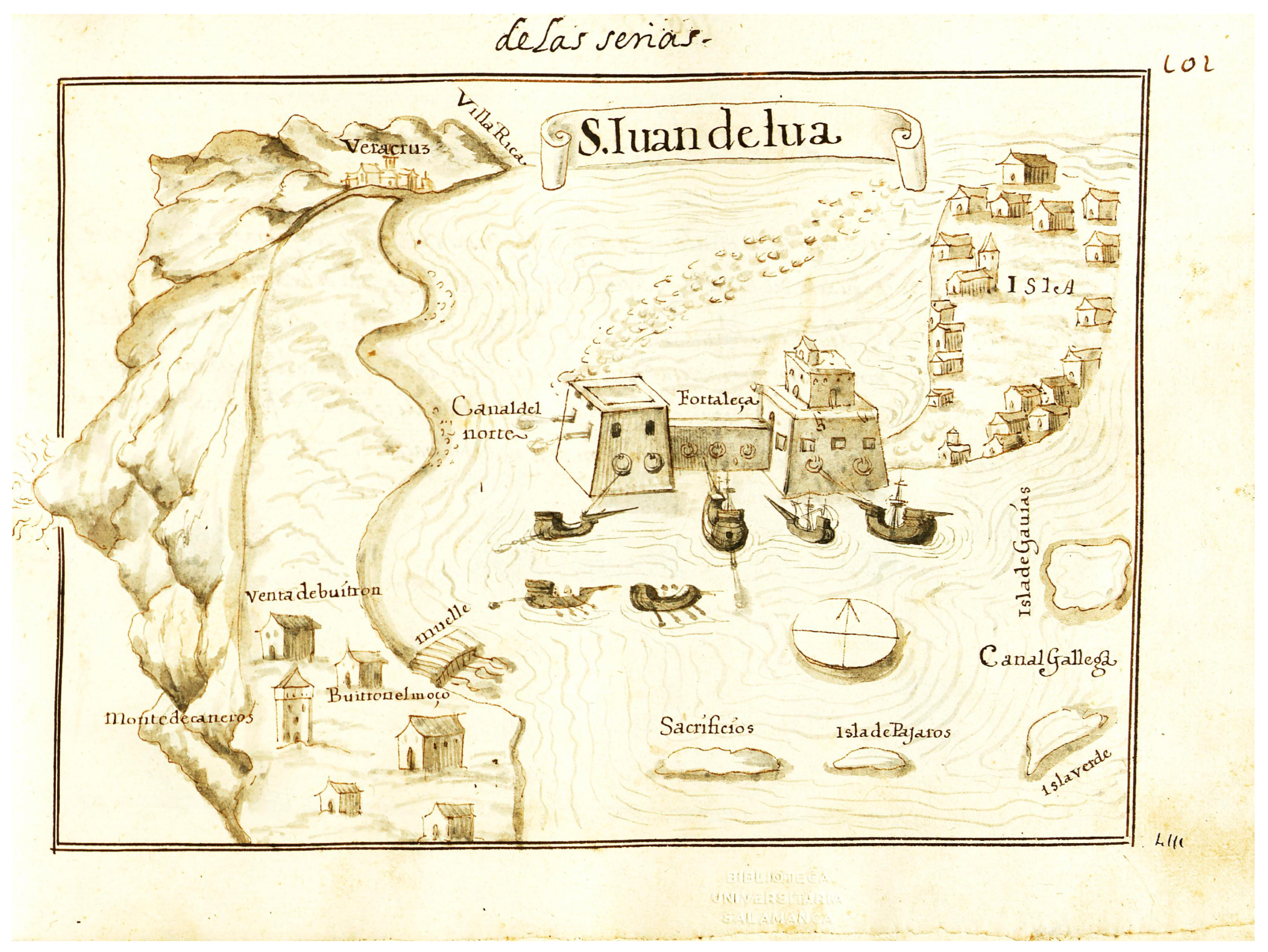

It is also relevant to consider the first city founded by Cortés: La Villa Rica de la Veracruz. Although the design of the original settlement remains unknown, it is documented that in 1524 the city was relocated to a more suitable site near San Juan de Ulúa, an island that served as both a defensive stronghold and a deep-water port. The initial settlement, known as La Antigua, did not exhibit a regular urban layout. While Cortés issued specific instructions regarding the distribution of plots and the alignment of streets to ensure a rectilinear arrangement, the resulting design fell short of achieving the precision associated with an ideal grid (

Figure 11).

4.5.1. What Did Royal Instructions Stipulate Regarding Cities in the New World?

In 1513, Charles V issued a directive to Pedrarias, later reiterated in subsequent ordinances, including one addressed to Cortés in 1523. This mandate established:

‘(…) you must distribute the plots of the settlement for the construction of houses (…) and from the beginning, they must be assigned in an orderly manner; so that, once the plots are established, the town appears ordered, both in the space left for the main square and in the placement of the church and the arrangement of the streets. For in places that are newly established, if order is set from the beginning, they remain structured without effort or cost, while in other cases, order is never achieved (…)’.

This passage underscores the importance of initiating urban development in a systematic and planned fashion. From the outset, plots were to be distributed in an orderly way to ensure that the town presented a coherent and harmonious appearance. The directive aimed not only at achieving practical efficiency in construction but also at symbolically reflecting a clear social and administrative order—an order that had to be evident from the very first stages of urban structuring.

Numerous studies have examined in depth the concept of the grid and the ideal of an ordered city in the New World (

García Zarza 1996;

López Guzmán 1997;

Sánchez de Carmona 1989). However, it is important to emphasise that, despite the extensive debate and analysis surrounding the implementation of these urban directives, when Cortés arrived in the Americas in 1519, he unexpectedly encountered a city that already displayed an ordered urban layout.

Later, in 1573, Philip II issued a major ordinance reflecting the evolving processes of urban foundation and planning. This document underscored the importance of designing the

planta—or basic layout—of settlements in a manner that organised public squares, streets, plots, and temples with precision and uniformity. It sought to reconcile urban expansion with the preservation of a pre-established order. However, as Terán notes, this legislation was enacted after the majority of major cities in the New World had already been founded—and since none of them fully conformed to the prescribed model—it stands as a clear example of a law that was never effectively implemented (

Terán 1999).

In conclusion, the royal directives reveal a clear intent to establish cities according to ordered and coherent layouts based on geometric and functional principles. Yet the case of Mexico-Tenochtitlan introduces a new dimension to this discourse, demonstrating that urban order in the New World also had indigenous roots and expressions. This invites further reflection on the interaction between European urban traditions and pre-Hispanic realities in shaping the character of colonial urbanism in the newly conquered territories.

4.5.2. What Was the Role of Hernán Cortés and Alonso García Bravo in the Founding of the City of Mexico?

Hernán Cortés is historically recognised as the founder of the new capital of New Spain, while Alonso García Bravo is traditionally credited with its urban planning. However, the precise contributions of each to the specific formulation of the city’s urban model remain the subject of ongoing scholarly debate. What is clear, however, is that both figures played pivotal roles in shaping an urban model that would have enduring influence well beyond their time.

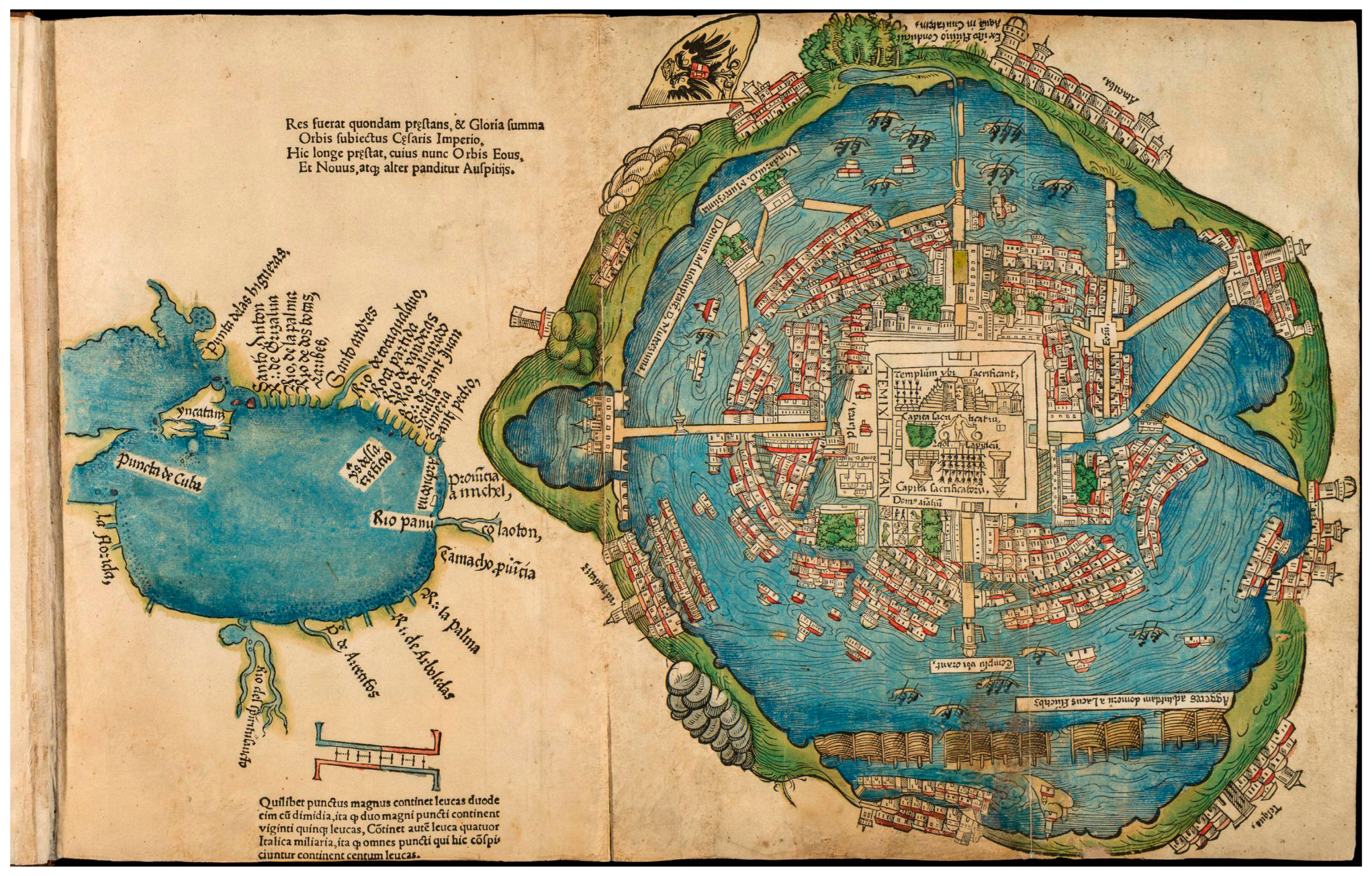

Cortés’s Second Letter of Relation to Charles V—often accompanied by a map attributed to him, although likely produced by another hand—depicted “Temixtitan” using Europeanised criteria. This representation imagined a medieval city that had never existed, but it captured the European imagination and contributed to the myth of a “fabled city” across the Atlantic. This reflects a broader tendency among Europeans to interpret American realities through their own preconceived frameworks and visual languages (

Miralles Ostos 2001).

Historians of the 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Lucas Alamán and Manuel Orozco y Berra, frequently dismissed indigenous urban contributions, regarding documents like the Maguey Paper Map as irrelevant for reconstructing the layout of the pre-Hispanic city. This Eurocentric bias deeply influenced early historiography, contributing to the widespread underestimation of Mesoamerican urban sophistication.

José R. Benítez, writing in 1933, was among the first to argue that García Bravo likely based the layout of the new city on the ruins of Tenochtitlan. His view helped challenge prevailing assumptions and marked an important step toward recognising the foundational role of indigenous spatial structures in the formation of colonial City of Mexico.

4.6. After Mexico-Tenochtitlan: The Emergence of Hybrid Urbanism in the City of Mexico

Following the prolonged and devastating siege that culminated in the final fall of Mexico-Tenochtitlan in 1521, Cortés made the momentous and strategic decision to establish the new capital of New Spain on the very site of the former Mexica metropolis. This choice represented a pivotal turning point in the urban configuration of the entire region. It was not merely a matter of founding an entirely new city on a vacant or untouched site; rather, it entailed the complex and demanding task of designing and structuring a Castilian city directly upon the physical remains—and the deeply ingrained urban logic—of a vast, sophisticated, pre-existing imperial centre (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

Thus, the newly christened capital, City of Mexico, did not arise arbitrarily or spontaneously but emerged as the intricate and fortuitous outcome of a fusion between two fundamentally distinct urban visions: the highly organised Mexica tradition, with its planned infrastructure, and the Castilian model, which introduced its own planning principles and royal mandates. Cortés was acutely aware that the advantages of rebuilding on the established site far outweighed the difficulties, especially given the city’s strategic location and its established function as an imperial hub (

Figure 14).

4.7. Continuity and Adaptation, a Hybrid Layout

The widely held belief that the Spanish conquerors completely erased all traces of indigenous urbanism following the fall of Tenochtitlan is, upon closer examination, demonstrably inaccurate. The Uppsala Map (also known Plano atribuido a Santa Cruz—Map Attributed to Santa Cruz) provides compelling visual evidence that the fundamental spatial logic of the Mexica capital was not only recognised but deliberately preserved. The Spanish retained the city’s four principal causeways, which served as the foundational axes for the traza or grid plan, and reutilised the central canal system originally engineered by the Mexica to regulate water levels. Numerous secondary infrastructural features—including minor causeways and drainage channels—were likewise maintained or adapted.

The present-day Zócalo (Plaza de la Constitución) occupies the site of the former ceremonial precinct, while the National Palace stands on the location of Moctezuma’s ‘new houses.’ Archaeological discoveries and colonial cartography consistently attest to this significant reliance on the pre-Hispanic urban framework in the early formation of the City of Mexico (

Campos Salgado 2006,

2011).

The Spaniards focused their architectural interventions on the central area known as the traza, where the earliest European-style buildings—including Cortés’s residence, the cabildo, and eventually the Cathedral—were constructed. Stones from the Templo Mayor were deliberately repurposed, serving both ideological and practical purposes: the destruction of indigenous ‘idolatry’ and the symbolic conquest of space. Yet, beyond this Spanish core, the wider morphology and functioning of the city remained deeply anchored in its pre-Hispanic origins.

Although the grid layout is commonly associated with Renaissance ideals, its presence in pre-Columbian cities such as Teotihuacan demonstrates that orthogonal planning was not an exclusively European innovation but had longstanding precedents within Mesoamerican urbanism.

A particularly striking example of continuity is the preservation of the city’s division into four

parcialidades, each corresponding to one of the cardinal quadrants of the Mexica city. These divisions endured throughout the colonial period, their Nahuatl names being Christianised as San Juan Moyotlan, Santa María Cuepopan, San Pablo Teopan, and San Sebastián Atzacualco. Numerous indigenous place names and spatial hierarchies persisted, as

Barbara Mundy (

2018) has demonstrated, while major centres such as Santiago Tlatelolco retained considerable indigenous autonomy well into the colonial era. Written accounts, including those by Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, further confirm that the visual and functional landscape of the city in the mid-16th century still bore the imprint of its pre-conquest configuration.

Institutionally, the city’s functioning also preserved significant indigenous structures. Cortés recognised the effectiveness of existing systems and strategically reinstated local elites, whose authority now derived from him rather than the deposed Mexica state. These leaders, together with indigenous engineers and artisans—many affiliated with specialised guilds or

calpulli—played a crucial role in maintaining and reconstructing the city. Their capacity to integrate new technologies within longstanding practices ensured the continuity and adaptability of urban life. As

Restall and Lane (

2018) have recently argued, indigenous agency in colonial city-building was not peripheral but foundational.

Despite the turbulence of the early colonial period—with its shifts in governance and land distribution—a more stabilised administrative structure emerged following the arrival of the Second Audiencia in 1530 and Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza in 1535. While the dynamics between the Spanish administration and indigenous governance remain deserving of further study, figures such as Diego Huanitzin, a noble descended from Moctezuma, were appointed as local governors, symbolising a negotiated continuity of power. By 1570, demographic records reveal that the City of Mexico was home to over 30,000 indigenous households, compared with fewer than 3000 Spanish ones, underscoring that the majority of urban life continued according to longstanding indigenous practices.

The

traza, traditionally credited to Alonso García Bravo, most likely constituted a formal survey of the pre-existing urban fabric rather than an original design created ex nihilo. It established spatial boundaries between Spanish and indigenous quarters, formalised property distribution, and adapted the underlying geometry of the Mexica city into a new orthogonal grid measuring six blocks wide by thirteen blocks long. In this respect, the City of Mexico represents an exceptional case: a colonial city laid out with remarkable geometric regularity, yet fundamentally built upon—rather than imposed over—the sophisticated urbanism of a pre-Hispanic capital. Prior to this, the Spanish had no consistent precedent for cities featuring strict orthogonal planning, whether on the Iberian Peninsula or in their early Caribbean settlements. Consequently, the design of the City of Mexico marked a foundational moment, blending Castilian planning ideals with Mesoamerican spatial logics, and establishing a model for future cities throughout the viceroyalty (

Toussaint 1956;

Carrera Stampa 1960).

4.8. The Hybrid Nature of Urban Transition

The transformation from Mexico-Tenochtitlan to Mexico was not a sudden rupture but rather a complex process of adaptation in which indigenous design principles endured profoundly. The inherent order and layout of the Mexica capital provided Alonso García Bravo with essential foundational elements, enabling the superimposition of a Castilian urban model without the need for wholesale destruction or complete re-engineering of the existing urban fabric. The regular dimensions and coherent spatial organisation of the Mexica city facilitated the precise distribution of streets and plots, thereby allowing the integration of the new orthogonal grid.

Accounts from Motolinia reveal the arduous and protracted process of demolishing Mexica structures to make way for new buildings, suggesting that the early Spanish city and the ruins of Tenochtitlan co-existed for several decades. Stones from these demolitions were likely repurposed to fill the canals between the chinampas, indicating that the ruined Tenochca buildings and chinampa systems fundamentally influenced the orientation, dimensions (blocks, streets, boundaries), and overall urban structuring of the new city through its existing road and hydraulic infrastructure.

Although the Spanish city was initially conceived as segregated—a ‘republic of Spaniards’ surrounded by indigenous settlements (calpulli)—these indigenous areas frequently expanded without strict adherence to European planning norms, resulting in what Spanish observers perceived as ‘disorder’. This segregation, combined with the legal and economic instability imposed upon indigenous and mestizo populations, led to distortions of the original grid in peripheral zones, thus exacerbating social divides between ethnic groups. Paradoxically, this lack of systematic European planning in these areas allowed indigenous urban practices to persist, which were later misinterpreted as an inability of non-Hispanic populations to conceive orthogonal urban layouts (

Toussaint et al. 1938;

Carrera Stampa 1949;

León-Portilla and Aguilera 2018) (

Figure 15).

A particularly intriguing facet of this hybrid urbanism lies in the reappropriation of indigenous sacred geometries to serve Christian symbolic purposes. The Mexica traza, marked by thirteen specific and profoundly significant nodes—rooted in Mesoamerican calendrical systems—was reinterpreted within the Catholic city of New Spain as representing Christ and the twelve apostles. This clever re-signification conferred upon Mexico the spiritual transcendence of a “Celestial Jerusalem,” a symbolic status that the absence of physical walls—a key element of urbanity and security in European medieval thought—might otherwise have negated. The quincunx pattern, formed by the strategic positioning of the four principal mendicant convents and the Cathedral, further reinforced this Christian symbolism, even though this geometric layout was originally derived from Mesoamerican cosmological concepts (

Palm 1951b;

Ezcurra 2006).

This blending of disparate cosmologies enabled the Spanish to adapt and legitimise their conquest and evangelisation within an existing symbolic landscape rich with meaning. The fact that the Mexica urban design, honed over centuries, embodied a sophisticated geometric regularity and sacred significance that coincided with certain European ideals was a considerable advantage for the Spanish. It meant the new viceregal capital could be constructed imbued with a sense of divinely ordained order that resonated with both indigenous and European notions of sacred space (

Urroz Kanán 2022).

Moreover, the technical knowledge and practical skills of the calquetzanime (Mesoamerican master builders) were indispensable to the Spanish. The expertise in urban surveying and construction developed by the Mexicas over nearly two centuries—and indeed by Mesoamerican cultures for over two millennia since the Preclassic era—was effectively transferred to Spanish urban planners. This enabled the Spanish to implement orthogonal grids in the New World with a scale and precision that surpassed previous attempts in the Iberian Peninsula or Caribbean colonies. As a result, the City of Mexico itself became the ‘prototype urban’ model that the Spanish Crown sought to establish, exemplifying a successful integration of Mesoamerican technological and design traditions.