Abstract

This study examines how the newly established United States pursued economic development through diplomatic and commercial initiatives with the Ottoman Empire, navigating regional powers and the era’s political-economic conditions. It analyzes using American archival sources how America endeavored to establish commercial and diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions, which it viewed as critical markets in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, before signing any formal agreement. The research tracks how these early efforts laid foundations for what would become one of the world’s largest economies. The study analyzes America’s diplomatic efforts to secure an agreement with the Ottoman Empire prior to the 7 May 1830 trade agreement—which laid the foundation for bilateral relations—alongside the reactions of regional powers, the prevailing conditions of the period, and the Ottoman administration’s reluctance due to various factors, based on U.S. archival sources that, to the best of our knowledge, have not previously been utilized in existing studies.

1. Introduction

In 1776, American independence fundamentally altered the balance of power in Eastern Mediterranean commerce, challenging an established order that had governed trade relations with the Ottoman Empire for centuries. United States of America (USA) policymakers immediately recognized that establishing the United States as a Mediterranean power required systematic engagement with this vital commercial region (Payaslian 2005, pp. 1–2; Kovalskyi 2020, pp. 55–57). America’s attempts to maintain and expand trade networks previously conducted under British protection now confronted the entrenched interests of established regional powers—Britain, France, and Russia—transforming routine commerce into complex diplomatic maneuvering.

Despite Turkish-American relations predating their formalization through the 1830 trade and a navigation agreement several decades old, scholarly attention has concentrated predominantly on post-1830 developments. The limited research examining earlier interactions approaches the subject from diverse analytical perspectives: systematic analysis of Ottoman–American political relations and capitulation demands from 1776 through World War I (Erhan 2000); examination of commercial relationships from 1830 to 1914 with indirect treatment of pre-treaty developments (Kara 2014); evaluation of naval conflicts between the United States and North African Barbary states during the 1780s–1815 period and their diplomatic ramifications (Lambert 2005); and analysis of early diplomatic, economic, and cultural exchanges spanning the 1780s to 1830, encompassing trade, missionary activities, and educational initiatives (Kayaoğlu 2021; Adams 2007).

This historiographical foundation, while valuable, inadequately addresses the sustained determination and sophisticated policy development required to establish official Ottoman–American relations. The present study prioritizes this historically complex process, examining how commercial engagement evolved from economic opportunity into a fundamental American policy objective and, ultimately, a struggle for regional survival and influence. Rather than treating early relations as a mere prelude to formal agreements, this analysis demonstrates how securing American interests within Ottoman territory became integral to the nation’s broader strategy of economic development and Mediterranean regional power projection.

American recognition of Mediterranean commercial potential preceded independence, with approximately one-sixth of total national exports directed toward the region by the early nineteenth century (McCusker 2010, pp. 7–24). Ottoman territory represented not merely an additional market, but an indispensable component of American commercial expansion. Initial trade volumes, though modest, demonstrated significant growth potential: from minimal pre-treaty levels to $560,000 following the 1830 agreement, reaching $815,000 by 1841 and $1 million by 1851. Additionally, eight American ships came to Izmir in 1816, 18 in 1823, 22 in 1825, 28 in 1828, and 32 in 1830 (Erhan 2001, p. 164; Köprülü 1987, p. 935). These figures underscore the agreement’s substantial economic benefits and validate American strategic calculations regarding Ottoman commercial engagement. The path to achieving such commercial success, however, required decades of persistent diplomatic effort.

Establishing formal commercial relations between the United States and the Ottoman Empire required decades of complex negotiations. Between 1790 and 1830, these negotiations shaped both commerce and diplomacy, fundamentally altering the balance of power in the Eastern Mediterranean. This study examines America’s persistent pursuit of formal relations prior to the 7 May 1830 treaty, the diverse responses of regional powers, and the Ottoman administration’s reluctance—all central to this investigation. Focusing on the pre-treaty period, the research analyzes American diplomatic strategy and maneuvering, as evidenced in U.S. archival documents.

Secret correspondence, reports, and diplomatic instructions between the U.S. Department of State and its diplomatic representatives in the Ottoman Empire, along with primary documents obtained from the Founders Online National Archives1 database, form the core of this study. Following correspondence with the Office of the Historian affiliated with the US State Department regarding archival transfers of materials exceeding thirty years, these State Department records were accessed through the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA, FM 77 ROLL 162)2 about a year ago. By analyzing these sources, we trace how American officials sought to advance bilateral relations, the obstacles they encountered, and how these efforts were perceived by American policymakers. Contemporary American newspapers also contribute to the analysis. In light of the historical context, we clarify how America sought strategic advantages in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea, attempted to develop ties with the Ottoman Empire and neighboring states, and aimed to increase trade—all from the American perspective.

2. Early Relations Between the USA and the Ottoman Empire

Following its 1776 independence, the USA quickly recognized the Mediterranean region’s strategic and economic significance. The Eastern Mediterranean, controlled by the Ottoman Empire through its North African provinces, constituted a vital commercial nexus that American leaders viewed as essential to their national development. The Ottoman Empire maintained a long-standing and influential presence in the Eastern Mediterranean through the semi-autonomous administrative structures known as the North African Barbary States (Algeria, Tunisia, and Tripoli) (Naylor 2016). America pursued Mediterranean trade on the belief that commercial engagement would secure international legitimacy for the new nation. Consequently, American strategists targeted the Eastern Mediterranean basin as a primary theater for commercial expansion and economic consolidation. In an official dispatch drafted while serving as minister to France, President Thomas Jefferson identified Mediterranean trade as critical to America’s economic future, arguing that its protection was vital for the republic’s survival. Jefferson wrote that this relationship embodied not only economic benefits, but also the principles of national dignity and sovereign independence (Founders Online, National Archives 1784a, November 11).

Americans had traded in the Mediterranean region even before independence. Trade connections established through colonial networks originated in the seventeenth century and expanded significantly following the thirteen colonies’ separation from Britain. Jefferson documented that America’s main exports during this period included salted fish, rice, timber products, grain, flour, and rum. These commodities represented significant components of America’s export economy—one-sixth of wheat and flour exports and one-quarter of dried fish shipments were destined for Mediterranean ports. Jefferson’s analysis indicated that pre-independence commerce employed about 1200 mariners and over 100 vessels, with a combined capacity exceeding 20,000 tons and generating profits comparable to those from other European markets. For example, Jefferson cited that American colonial exports to Mediterranean destinations in 1770 totaled 707,000 pounds sterling (Founders Online, National Archives 1784a, November 11). These figures clearly showed the Mediterranean trade’s critical importance to pre-independence American commerce.

Succeeding independence, securing Mediterranean trade access, developing new markets, and establishing control over regional maritime routes became the USA’s top priorities. Facing various diplomatic challenges, particularly with Britain, American leadership prioritized rapid foreign trade expansion and financial consolidation. Consequently, Ottoman-controlled territories attracted significant attention from America’s newly established government. While American merchant vessels had previously operated throughout the region under British protection, independence ended this arrangement as Britain withdrew its protective aegis from American shipping in Eastern Mediterranean waters (McNamara 2018). Thus, this diplomatic shift left American vessels unprotected, making them vulnerable to attack.

Particularly threatening were corsair vessels affiliated with the Barbary States, whose Eastern Mediterranean operations seriously threatened American commerce. These semi-autonomous states—operating within the Ottoman sphere—became strategic actors in Eastern Mediterranean politics, using their naval strength in both trade and conflict. During the twenty-four-year Cretan War between Ottoman and Venetian forces, Barbary corsairs provided crucial naval support to Ottoman fleets (Mantran 1995, p. 7). Regional powers systematically exploited these corsair operations to maintain commercial supremacy. In a correspondence to American diplomat Benjamin Franklin in 1783, French consular official Jean-Antoine Salva warned of imminent threats to American shipping, revealing planned corsair interceptions of vessels departing Marseille that March. Salva also criticized the duplicitous policies of European states, noting that they not only paid tribute to the corsairs, but also used them as instruments against commercial rivals (Founders Online, National Archives 1783c, April 1). This correspondence makes it clear that corsair activity was a tool of great power rivalry, not mere piracy, and put American trade at substantial risk. Swift Barbary vessels compelled American ships throughout North African waters to seek refuge in Italian harbors, with those unable to reach safety facing seizure (Breitman n.d., p. 2). Within a decade of American independence, corsairs had captured three American vessels (Carriero 2008, p. 75).

The earliest unofficial interactions between the USA and Ottoman Empire emerged during this period through indirect channels. To address these attacks, U.S. diplomats initiated systematic intelligence-gathering regarding Barbary states’ political structures, strategic intentions, European diplomatic relationships, and regional conditions (Founders Online, National Archives 1786a, April 2). American leadership sought a detailed understanding before advancing diplomatic initiatives. John Lamb, New York’s Customs Director dispatched on diplomatic assignment, reported to American Commissioners that despite three audience sessions with Algeria’s Dey, peace negotiations had failed as the ruler demanded exorbitant ransoms for captive Americans—totaling 59,496 Spanish dollars. Lamb’s assessment clarified Algeria’s political status: nominally under Ottoman control but functionally autonomous. He noted that despite receiving external support from influential European states, Ottoman control remained limited. Lamb documented Algeria’s economic foundation—predicated on piracy, captive ransoms, and taxation—while providing detailed assessments of its naval capabilities and land forces (Peskin 2009, pp. 24, 96–8). His diplomatic calculus suggested that negotiated settlement would prove less costly than military confrontation, estimating first-year war expenditures could exceed half a million pounds sterling (Founders Online, National Archives 1786c, May 20). The US Eastern Mediterranean policy was thus shaped by intelligence gathered through these diplomatic missions, with officials analyzing both the motives of Barbary rulers and the influence of European powers. The information collected confirmed the Ottoman Empire’s regional dominance and the importance of its position in both commerce and geopolitics.

Recognizing Eastern Mediterranean commerce as vital to national prosperity, America initially pursued diplomatic accommodation with regional powers and Barbary states to safeguard its trade interests (Marzagalli 2010, pp. 46–47). In a correspondence dated 10 September 1783, addressed to Congressional President Elias Boudinot and future president John Adams, alongside Benjamin Franklin and Secretary of State John Jay, emphasized the growth potential of American Eastern Mediterranean commerce and advocated establishing amicable relations with Ottoman tributaries including Algeria, Tunis, and Tripoli (Founders Online, National Archives 1783b, September 10). A subsequent committee report co-authored by Thomas Jefferson recommended negotiating friendship and commercial treaties with both the Ottoman Empire and North African states, proposing agreements extending ten years or longer (Founders Online, National Archives 1783a, December 20). American leadership swiftly concluded that national economic expansion required establishing cordial commercial ties with Ottoman-affiliated Barbary regencies (Irwin 1931, p. 37).

Congress responded by establishing a diplomatic commission empowered to propose, negotiate, and ratify treaties of friendship and commerce. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin were appointed as commissioners with two-year mandates. Congressional instructions issued between 7 May 7 and 3 June 1784, directed the commission to secure enduring treaties with European and Mediterranean powers, including the Ottoman Empire, and to seek favorable commercial terms for American trade in both European and Asian Ottoman territories (Founders Online, National Archives 1784b, May 7). This directive clearly demonstrated America’s systematic efforts to establish formal diplomatic and commercial relations with both the Ottoman Empire and its North African dependencies. A 1783 document even proposed the creation of an American consulate in Istanbul and named Charles Mace—former secretary to Britain’s ambassador—as a candidate, marking an early step toward establishing official contacts (Founders Online, National Archives 1783d, January 28).

Drawn by Ottoman commercial potential, the USA initiated direct trade with Izmir in 1785, leveraging support from the British Near East Company (Howard 1976, p. 293). İzmir was the Ottoman Empire’s chief commercial center and the hub of Levantine trade. This policy, aimed at safeguarding American commercial interests, gradually intensified. Consequently, the United States concluded formal agreements with numerous states, particularly the Barbary states (Kaya 2024, pp. 321, 328). To secure maritime protection, the United States agreed to annual tribute payments to Barbary rulers—a significant burden for the new nation, but necessary to maintain access to Eastern Mediterranean trade.

America’s pursuit of commercial and friendship treaties must be contextualized within its broader strategy to expand global trade networks. However, this diplomatic initiative encountered complications stemming from European powers’ entrenched regional interests. The strategic calculations and competing influences of Britain, France, and Russia regarding the Ottoman Empire directly impacted American commercial and diplomatic overtures. Consequently, the USA committed substantial resources to cultivating Ottoman relations (Kayapınar 2017, pp. 41, 45, 50). Diplomatic engagement, particularly with Barbary states, routinely necessitated lavish gifts and strategic payments. Contemporary documentation reveals that regional administrations operated through institutionalized gift-giving and unofficial payments, with foreign representatives compelled to provide customary offerings to facilitate official business (Founders Online, National Archives 1786a, April 2). The USA incurred significant expenses in dispatching valuable presents to secure peace agreements with these regencies. Algerian, Tunisian, and Tripolitan authorities consistently demanded military provisions and ceremonial gifts—requirements that complicated America’s diplomatic position while increasing its financial obligations, yet exemplified its determination to establish regional commercial footholds (Irwin 1931, p. 45). Nevertheless, gift diplomacy constituted only a temporary solution in Barbary relations. The effectiveness and durability of these agreements varied with changing political and economic circumstances. Early on, U.S. leaders believed war would be too costly and ineffective (Founders Online, National Archives 1786b, June 26), but this view later shifted: tribute was seen as unsustainable, and military action became more attractive (Founders Online, National Archives 1790, July 12). Jefferson eventually advocated a multinational coalition against the Barbary states, European powers, however, rejected collaborative approaches, preferring to continue tribute-based commercial security (Jewett 2002, p. 1). Seeking a more permanent resolution, USA accelerated efforts to establish direct diplomatic and commercial relations with the Ottoman Empire—a development that would secure Eastern Mediterranean trade while enabling more effective strategies against Barbary corsairs, facilitate commerce through vital ports like Izmir, and strengthen American merchants’ regional presence.

The United States increasingly recognized the Ottoman Empire’s pivotal strategic position. From the 1790s onward, America intensified diplomatic initiatives to secure regional advantages. Thomas Jefferson exhibited particular interest in Ottoman territories, investigating potential American economic applications for regional agricultural products including figs, raisins, and pistachios. In a correspondence, John Rutledge Jr.3 advocated exploration of Ottoman lands, noting that “the olive tree in particular has great economic potential for South Carolina and Georgia” (Founders Online, National Archives 1788, June 19). Additional documentation analyzed potential commercial benefits of Ottoman–American Eastern Mediterranean trade, observing underdeveloped Ottoman agricultural and fishery sectors that presented export opportunities for American rice, grain, meat, fish, tobacco, and timber. The assessment suggested such trade would stimulate American agricultural expansion while strengthening national economic foundations, emphasizing the significance of securing Ottoman diplomatic support (Founders Online, National Archives 1789, August 3). Archival evidence indicates American leadership methodically assessed regional commercial viability to establish reciprocal interests and common ground for economic partnership.

In a correspondence addressed to President George Washington on 27 July 1796, Secretary of State Timothy Pickering referenced Algerian Consul Joel Barlow’s report emphasizing the imperative of establishing formal commercial and diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire. Concurrently, David Humphreys, American ambassador to Spain, recommended arranging commercial privileges and protection for American citizens from Sultan Selim III, identifying Barlow as the optimal candidate for Ottoman and broader Mediterranean negotiations (Founders Online, National Archives 1796, July 27). In a 8 February 1799 communication to the Senate, President John Adams proposed appointing William Smith as ambassador extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to the Ottoman Empire, with comprehensive authorization to negotiate a formal friendship and commercial treaty (Founders Online, National Archives 1799a, February 8). This appointment represented a concrete diplomatic initiative toward establishing official Ottoman–American relations and negotiating binding commercial agreements through formal diplomatic channels—constituting a significant advancement in America’s systematic effort to achieve official diplomatic engagement with the Ottoman Empire.

3. The Process Leading to a Trade Agreement in Ottoman–American Relations in the 19th Century

Ottoman–American relations during the nineteenth century evolved through complex diplomatic negotiations characterized by mutual challenges. Throughout this period, the USA predominantly initiated efforts to develop bilateral relations (Avcı 2016, pp. 1–12). This American activism reflected the country’s rising global stature and expanding commercial ambitions, supported by a strategy of neutrality in European affairs. The United States had emerged as an increasingly acknowledged rising power within the international system (Yılmaz 2015, pp. 9–40). Diplomatic correspondence between Secretary of State Timothy Pickering and President George Washington revealed that major powers including Russia and England had expressed approval regarding potential American commercial treaties with the Ottoman Empire. Consistent with diplomatic protocols, these communications emphasized the necessity of presenting appropriate gifts corresponding to Ottoman officials’ hierarchical positions during negotiations. The document referenced England’s customary diplomatic presents to Ottoman authorities, noting their approximate value at 3000 pounds sterling. The U.S. officials proposed allocating between 40,000–50,000 dollars for comparable diplomatic offerings, characterizing this expenditure as modest when weighed against the anticipated long-term benefits of a formalized Ottoman agreement (Founders Online, National Archives 1799b, February 8). This documentation suggests that while established regional powers maintained certain reservations, they recognized America’s growing position and, in private, sometimes encouraged Ottoman engagement. The United States, in turn, was prepared to make various concessions, including financial ones, to achieve its strategic goals.

The primary impediment to establishing formal commercial relations between the United States and Ottoman Empire remained the persistent Barbary corsair attacks against American vessels throughout Eastern Mediterranean waters. These attacks absorbed diplomatic energy and resources, making it difficult to advance other priorities. Escalating tribute demands and ceremonial gift requirements from regional regencies strained negotiated agreements and undermined diplomatic sustainability (Smith 2006, pp. 509–10). In a correspondence from Tunisian ruler Hamuda Pasha to Thomas Jefferson, the Bey explicitly warned that bilateral relations would deteriorate without fulfillment of specified tribute payments and customary gifts (Founders Online, National Archives 1801a, April 15). In responsive communication to Tripolitan ruler Yusuf Karamanli, Jefferson diplomatically rejected excessive tribute demands while asserting that enduring friendship agreements must rest upon reciprocal interests rather than unilateral concessions (Founders Online, National Archives 1801b, May 21). This refusal to comply with ever-increasing demands marked a significant change in American strategy: the United States stopped tribute payments and resorted to military force against the Barbary states, a decision that postponed progress in relations with the Ottomans themselves. The conflicts with the Barbary regencies from 1801 to 1815 were the main reason for the delayed development of formal Ottoman–American relations. American diplomatic initiatives toward comprehensive Ottoman agreements temporarily receded as resources were concentrated on this immediate strategic priority.

European powers’ entrenched influence within the Ottoman Empire constituted another significant obstacle to establishing formal Ottoman–USA relations. Specifically, England and France’s longstanding commercial connections with the Ottoman state led to calculated interventions to preserve their privileged positions (Geyikdağı 2011, pp. 530, 535). In a correspondence from Tunisian Consul William Eaton to Secretary of State James Madison, Eaton observed that evolving European political developments could significantly impact Ottoman orientation and consequently American interests (Founders Online, National Archives 1802, December 20). France’s expansionist policies and European power rivalries indicated potentially rapid regional realignments. In a diplomatic assessment from Italian Consul Thomas Appleton to Madison, he projected that should European developments force Ottoman realignment, the Empire would likely form an alliance with Britain against France (Founders Online, National Archives 1803, October 7). These sources show that American officials were acutely aware of the constant risk of diplomatic setbacks due to European interference, even when European governments publicly encouraged American–Ottoman relations. Nevertheless, American government maintained persistent diplomatic initiatives, recognizing that the Ottoman Empire’s strategic position represented an essential foundation for both expanding American commerce and securing competitive advantages against European rivals (Payaslian 2005, pp. 3–7).

American policymakers recognized the potential advantages of a trade agreement with the Ottomans while simultaneously working to resolve existing obstacles (Alrefae 2024, pp. 1769–70). In a correspondence from Thomas Appleton to James Madison dated 26 May 1804, Appleton stressed the critical importance of establishing a commercial treaty with the Ottoman Empire. He noted that without such an agreement, Ottoman authorities would not formally acknowledge an American presence on imperial soil. Appleton argued that a treaty would create significant opportunities for the USA to strengthen its Eastern Mediterranean trade networks. He specifically identified Black Sea goods such as hemp, sailcloth, and iron as obtainable at 40% lower cost through direct Ottoman trade—advantages lost without formal access (Founders Online, National Archives 1804b, May 26).

The United States, cognizant of the strategic necessity for an Ottoman trade agreement amid shifting geopolitical dynamics, increasingly appreciated the Black Sea’s commercial value (Kayapınar 2017, pp. 45–46). In a dispatch to James Madison, Levett Harris, the American consul in St. Petersburg, Russia, underscored the Black Sea’s significance. His communication emphasized how crucial it was for the United States to secure unrestricted trading rights in these waters. Harris indicated that following an Ottoman trade agreement, vessels under American flags would gain free navigation access throughout the Black Sea, a region he described as possessing exceptional commercial potential due to its strategic geographic position (Founders Online, National Archives 1804a, June 29). As trading opportunities expanded, the United States demonstrated greater willingness to develop Ottoman relations. The American administration sought to extend to its own traders the advantageous status enjoyed by European merchants, particularly regarding Black Sea access privileges—fundamental principles in any proposed trade agreement. The Ottoman Empire, however, was typically reluctant to grant such concessions, resulting in long and difficult negotiations (King 2004, pp. 109–36).

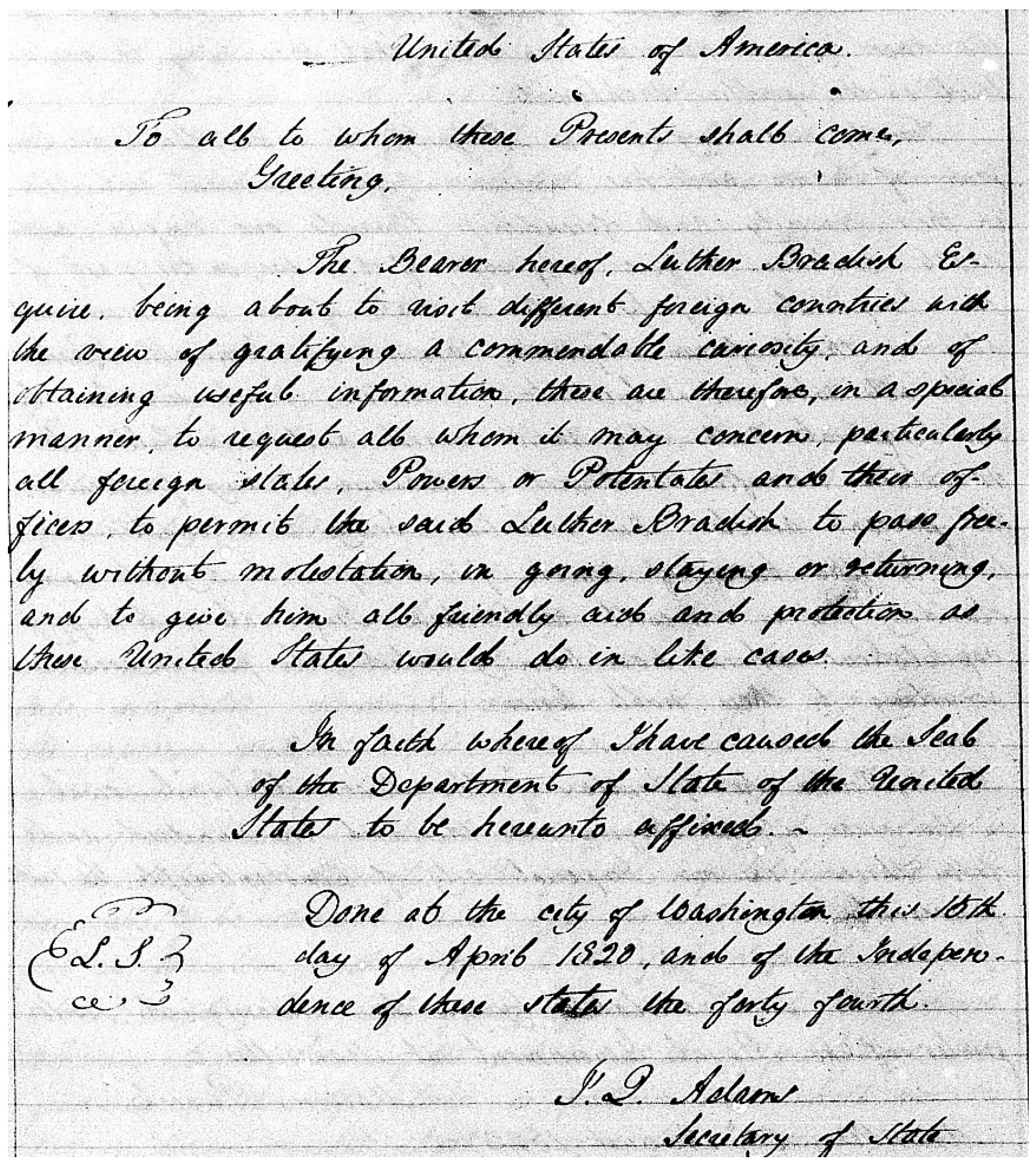

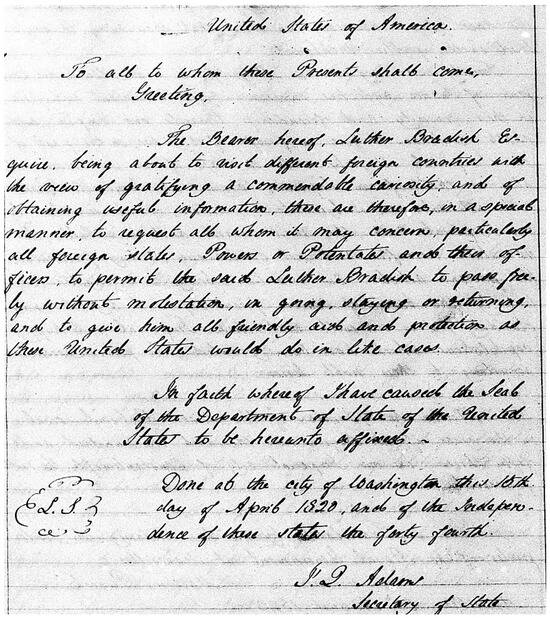

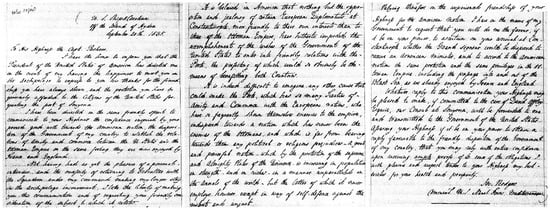

American representatives deployed diverse strategies to advance their national interests. Initially, they gathered intelligence through appointed agents to comprehend Ottoman intentions and establish foundations for future negotiations. From 1820 onward, Ottoman officials began expressing concerns that regional powers might unify against them, potentially leveraging American support during conflict. Consequently, despite lacking a formal agreement, Ottoman authorities increasingly articulated the necessity of cultivating American friendship through unofficial diplomatic channels (BOA4, HAT5 (BOA, HAT, 1820)). On 15 April 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams unofficially assigned Luther Bradish6 to collect information about the Ottoman Empire, determine potential trade agreement parameters, and safeguard American interests (NARA 1820a, April 15, p. 176). Bradish received a specialized passport with presidential instructions to seek assistance in countries along his route (see Figure 1). The American Senate directed him to investigate whether a trade agreement with the Ottoman Empire would benefit the United States, assess its feasibility, determine negotiation approaches, yet present himself merely as an ordinary American citizen. This strategy reflected the belief that the Ottomans would negotiate only with specially authorized emissaries, and that informal intelligence gathering would be more effective. In his subsequent report, Bradish documented meetings with high-ranking Ottoman officials in Istanbul where he communicated American interest in establishing friendship and trade agreements while exchanging perspectives on negotiation procedures. He provided detailed analysis of Ottoman internal governance structures, political circumstances, and European diplomatic relations. Bradish’s report noted British-circulated rumors of a secret American–Russian alliance, which increased Ottoman suspicion. He argued that direct negotiation was the most effective approach, citing Britain’s four-year failed attempt to secure an Ottoman agreement on India’s behalf. Bradish reported that Britain threatened war if the Ottomans made an agreement with the United States, while Austria, France, and the Netherlands opposed such moves less directly. Bradish’s report also addressed financial considerations, estimating negotiation costs not exceeding 350,000 kuruş, noting the Turkish kuruş was valued then at 3/15 of a Spanish dollar and 1/95 of a British pound (NARA 1820b, December 20, pp. 177–95). The Ottoman administration’s principal apprehension centered on the possibility that the United States might exploit North African Barbary States (the region known in Ottoman archival sources as the “Garp Ocakları”) disputes as pretext for regional power intervention. Ottoman documents emphasized that such developments would ultimately disadvantage American interests, suggesting direct Ottoman–American negotiations would prove more effective. Alternative approaches might necessitate American military action—a prospect Ottoman authorities viewed unfavorably (BOA, HAT, 1820). On 18 November 1821, Ottoman officials informed Bradish that immediate commercial treaty implementation seemed inappropriate, citing geographical distance between the nations as rendering such arrangements economically unfavorable for Ottoman merchants. Bradish countered that prospective agreements would safeguard mutual commercial interests rather than exclusively benefit American traders, requesting Ottoman authorities conduct comprehensive analysis before reaching definitive conclusions (BOA, HAT, 1821). Through comprehensive reporting on his Ottoman official contacts, Bradish provided crucial intelligence to American administrators, significantly contributing to groundwork for future negotiations. Nevertheless, his limited authority, combined with Ottoman internal challenges and European powers’ interventions, ultimately impeded his efforts to secure an agreement (Vivian 2015, pp. 2–3).

Figure 1.

Document from John Quincy Adams to Luther Bradish requesting assistance in the countries he was visiting on behalf of the US government (Source: NARA, FM 77 Rol 162, p. 176).

The Ottoman Empire’s confrontation with the Greek rebellion transformed its diplomatic stance toward European powers (Clark 2013). Despite initially displaying amicable intentions toward the United States, mutual suspicion deepened over alleged American support for Greek rebels and Bradish’s suspected covert activity (NARA 1823c, December 27, pp. 80–84). Recognizing this deterioration, the American government commissioned George Bethune English7 on 2 April 1823, to investigate causes underlying the diplomatic impasse (NARA 1823a, April 2, p. 92). English was instructed to report directly to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, providing confidential assessments on potential strategies for diplomatic renewal. In his inaugural 1823 report, English candidly acknowledged his intelligence-gathering operations within Ottoman territories and committed to regular correspondence with the State Department. He documented his contacts with Ottoman officials and outlined new approaches for formal diplomacy, especially emphasizing Istanbul’s commercial importance and the significant profits made by foreign (Frank) merchants compared to Americans. English particularly emphasized Istanbul’s commercial significance, noting, “Frank merchants are generating substantial profits in Istanbul,” while lamenting that American traders had difficulty penetrating this lucrative marketplace (NARA 1823b, November 23, pp. 77–80). His 27 December 1823 dispatches revealed discriminatory tariff structures—foreign merchants paid 3% customs duties while American traders faced an additional 2% surcharge. English detailed promising discussions with key Ottoman officials, including the Kapudan Pasha (Grand Admiral of the Ottoman Navy) and Foreign Minister, regarding potential trade agreements. He specifically suggested that a clandestine meeting between the commander of the American fleet in the Mediterranean and the Kapudan Pasha could facilitate breakthrough negotiations. According to English, the Admiral expressed willingness toward American rapprochement while maintaining specific conditions; following such consultation, the Sultan would likely render favorable decisions (NARA 1823c, December 27, pp. 80–84). English’s unofficial diplomatic status ultimately undermined his effectiveness, as Ottoman protocols required fully empowered representatives for formal treaty negotiations (Örmeci and Işıksal 2020, p. 98). Consequently, in his 14 May 1824 communication, English advocated direct governmental intervention through official diplomatic correspondence, volunteering to personally deliver such communications (NARA 1824, May 14, pp. 104–6). Both Bradish and English’s diplomatic initiatives significantly influenced American strategic positioning throughout the region, establishing critical foundations for eventual formalization of Ottoman–American commercial relations.

Ottoman reservations regarding American trade agreements stemmed from multiple considerations: first, a perceived imbalanced commercial opportunity due to limited existing trade relations, with disproportionate American advantage; second, concerns that treaty provisions would strengthen American naval capabilities that could be deployed against Ottoman interests; third, British opposition to a potential agreement and their efforts to preserve commercial primacy (BOA, HAT, 1820). Following these unsuccessful initiatives, on 7 February 1825, the American government commissioned the commander of its Mediterranean fleet, Captain John Rodgers, to examine the possibility of a trade agreement with the Ottoman Empire (NARA 1825a, February 7, pp. 108–9). The administration authorized George B. English to serve as Rodgers’ interpreter and perform supplementary duties under his command (NARA 1825c, January 3, p. 108). American diplomatic objectives included securing most-favored-nation status comparable to France’s privileges, obtaining unrestricted Black Sea navigation rights and establishing consular representation throughout Ottoman territories (NARA 1825d, September 6, pp. 110–11). Rodgers’ mission entailed meeting with the Kapudan Pasha (Husrev Pasha) to assess receptiveness toward these objectives and prepare foundations for formal negotiations (Andrianis 2021, p. 9). Should the Pasha demonstrate favorable disposition toward an agreement, Rodgers was instructed to discreetly inform the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The American government authorized Rodgers to present appropriate diplomatic gifts to Kapudan Pasha contingent upon successful preliminary negotiation (NARA 1825b, February 7, p. 109).

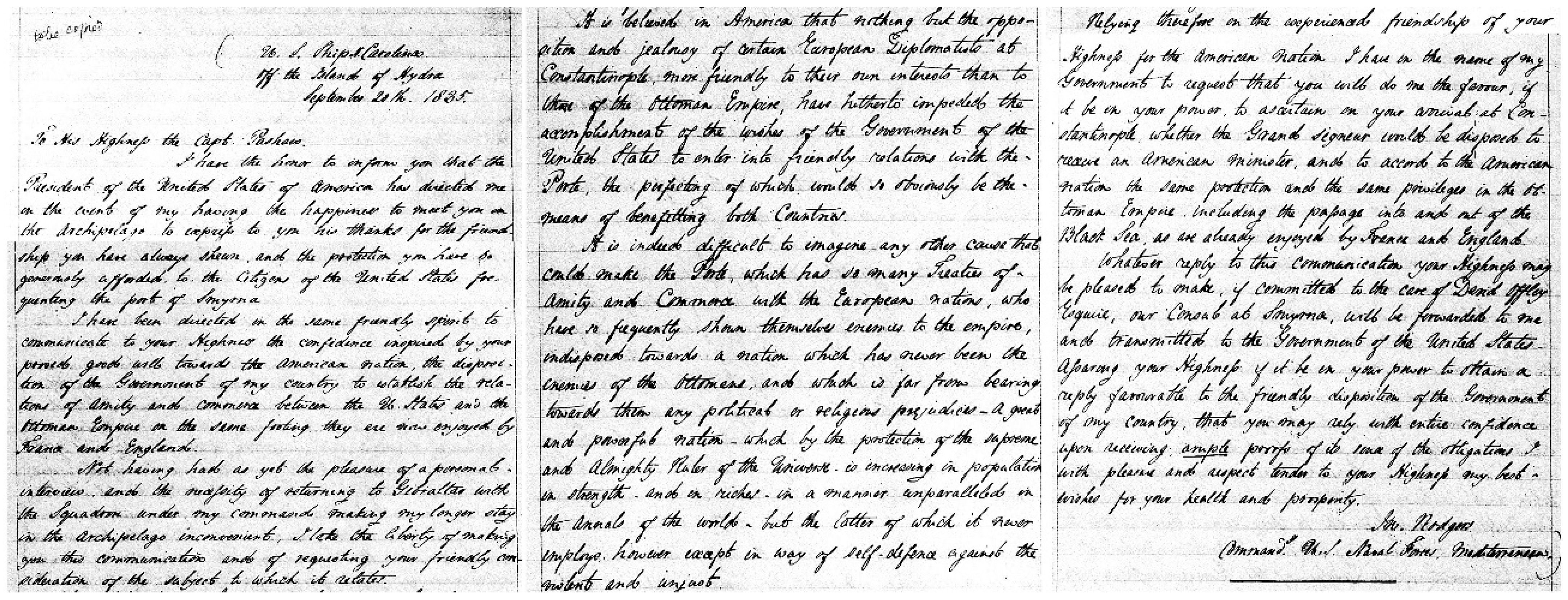

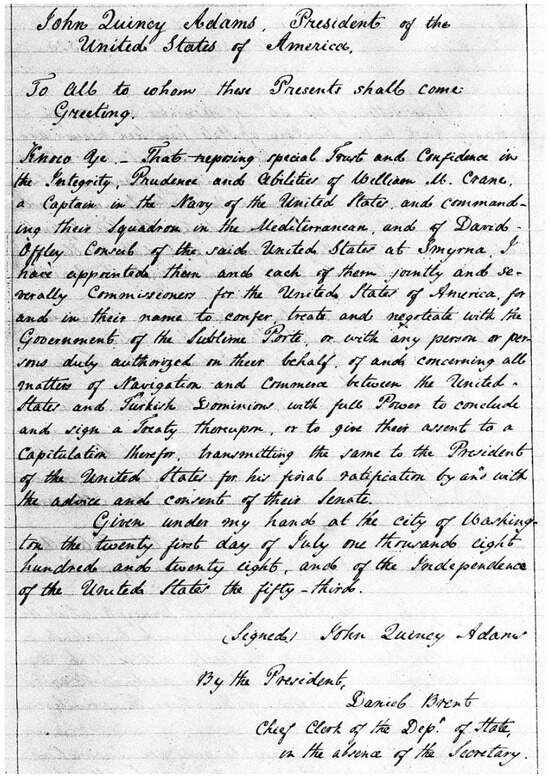

Throughout his assignment, Captain Rodgers dispatched detailed assessments to Secretary of State Henry Clay regarding Ottoman political conditions, developments in the Greek insurrection, and intricate European power dynamics in the region (Hatzidimitriou 2002, pp. 260–76). While seeking audience with Kapudan Pasha, Rodgers expressed reservation given the Admiral’s limited military success against Greek revolutionaries. Concluding that the Kapudan Pasha’s precarious position complicated potential American–Ottoman agreements, Rodgers deemed direct meetings excessively risky, opting instead for written communication on 28 September 1825 (see Figure 2) (NARA 1825e, September 28, pp. 8–10). His correspondence succinctly expressed American desire to establish diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire, requesting the Captain Pasha’s assistance in determining whether an American envoy would receive imperial reception. In subsequent State Department communications, Rodgers characterized the Greek rebellion as a cause commanding civilized world sympathy while noting European powers’ self-interested approaches toward the conflict. He advocated maintaining America’s amicable neutrality throughout this confrontation while noting the Admiral’s continued unresponsiveness to his overtures (NARA 1825f, November 30, pp. 14–17). Rodgers’ dispatches explicitly articulated American commercial and diplomatic challenges regarding Ottoman engagement while proposing strategic approaches to overcome these obstacles. His reports emphasized how Ottoman preoccupation with suppressing the Greek revolution, compounded by European powers’ ambivalent positions, significantly complicated potential trade agreement negotiations. The communications underscored Black Sea access and equitable commercial arrangements as strategic imperatives for expanding American trade networks. Nevertheless, Rodgers counseled Washington that successful Ottoman diplomatic engagement would necessitate patient, methodical approaches to achieve these ambitious commercial objectives.

Figure 2.

Letter sent by Captain Rodgers to the Kaptan-ı Derya on 28 September 1825. (Source: NARA, FM 77 Roll 162, pp. 8–10).

In a later report to Secretary of State Henry Clay dated 19 July 1826, Rodgers chronicled his long-anticipated audience with the Kapudan Pasha and detailed the outcomes of their discussions. The interview was conducted on the island of Mytilini (Andrianis 2021, p. 9). During these deliberations, Rodgers emphasized the necessity of establishing a formal treaty with the Ottoman Empire to enhance commercial relations and secure expanded privileges for American merchants operating within Ottoman ports. He specifically advocated for mutual “most favored nation” status between the two countries’ citizens. The Admiral pledged to inform Sultan Mahmud II regarding such potential agreements while expressing his personal support for advancing negotiations. During their exchange, the Pasha conveyed the Sultan’s favorable disposition toward American interests, symbolically presenting Rodgers with an imperial portrait as tangible evidence of this goodwill. Throughout these diplomatic encounters, Ottoman officials exhibited cordial attitudes toward the United States, exchanging ceremonial gifts with the American representatives while emphasizing the need to enhance the bilateral relationship. Rodgers noted that David Offley and George B. English attended these significant meetings, highlighting Offley’s instrumental role in facilitating communications with Ottoman authorities (NARA 1826, July 19, pp. 30–35). Rodgers thus achieved his primary objective—securing direct dialogue with the Ottoman Kapudan Pasha. His comprehensive report reveals the constructive nature of these discussions, which constituted a pivotal formal initiative toward strengthening diplomatic relations between both nations. This diplomatic breakthrough reaffirmed the strategic wisdom of America’s steadfast commitment to avoiding entangling European political alliances while maintaining strict neutrality in regional conflicts—policies that significantly enhanced American diplomatic credibility among Ottoman officials.

The USA consistently pursued Ottoman–American relations enhancement from their inception (Adams 2007). However, the Ottoman naval defeat at Navarino fundamentally reversed this diplomatic dynamic. American newspaper Phenix characterized the Ottoman naval catastrophe as a triumphant Greek victory, describing it as a significant advancement in preserving Greek national honor, combating regional piracy, and safeguarding allied nations’ commercial interests (Cochran 1828, p. 2). Another edition of this publication noted that while Navarino substantially diminished Ottoman naval capabilities, acknowledging Greek independence at that time was considered premature (Phenix Gazette 1828, p. 3). Nevertheless, this conflict profoundly disrupted Ottoman domestic governance and foreign policy implementation (Ozavci 2023, pp. 222–37). Nicolas Marmi, who facilitated Ottoman–American diplomatic exchanges, reported to Secretary of State Henry Clay on 24 January 1828, that pre-1827, America persistently sought formal agreements, whereas subsequently, Ottoman enthusiasm for such arrangements markedly intensified (NARA 1828b, January 24, pp. 57–63). David Offley’s correspondence to Henry Clay dated 26 November 1827, corroborates this diplomatic reversal. This document records the unprecedented development of prominent Ottoman military commander Serasker Hüsrev Pasha extending a formal invitation to Offley, requesting his presence in Istanbul for trade agreement deliberations (NARA 1827, November 26, pp. 39–42). In subsequent correspondence to Clay dated 17 February 1828, Offley noted that Ottoman Foreign Minister Reis Efendi (Mehmet Akif Efendi) directly communicated Ottoman eagerness for treaty negotiations, expressing a readiness to commence discussions immediately. Ottoman officials signaled willingness to accept critical provisions previously emphasized in American proposals (NARA 1828a, February 17, pp. 42–45). The Foreign Minister further conveyed Sultan Mahmud II’s explicit support for American commercial vessels operating in Ottoman harbors, his desire for expanded bilateral relations, and his directive that American merchants receive equal treatment as other foreign traders. The Austrian ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, in his 29 November 1827 dispatch, highlighted potential benefits from expanded American trade relations. His analysis criticized British opposition while emphasizing potential economic and political advantages through formalized agreements. The ambassador further suggested that cultivating American diplomatic goodwill might prove instrumental in suppressing Greek revolutionary activities (BOA, HAT, 1827). Following the Navarino debacle, Ottoman leadership actively sought to cultivate relations with the neutral yet increasingly powerful United States, recognizing the strategic value of securing such a formidable diplomatically (Örmeci and Işıksal 2020, p. 23).

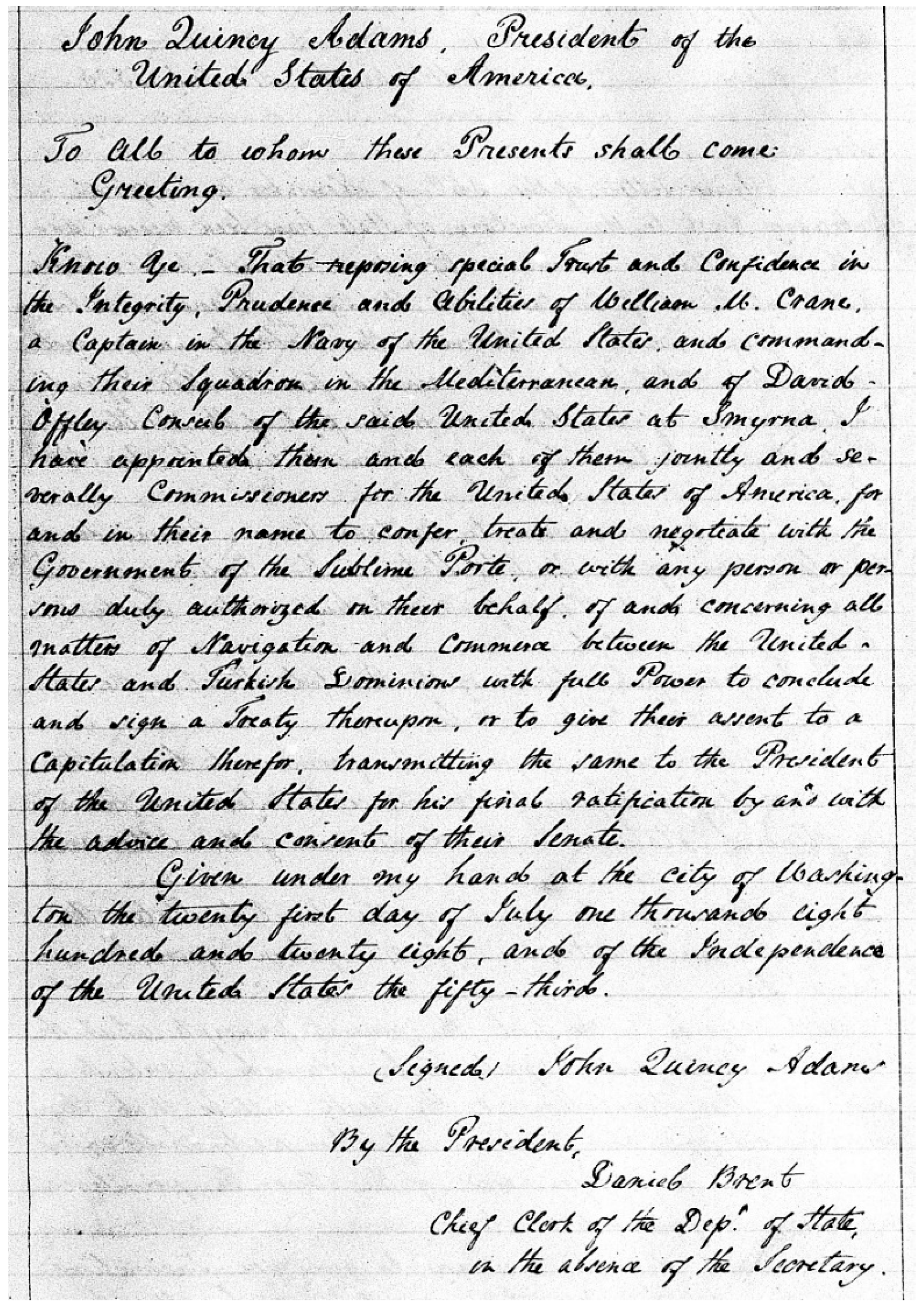

The American administration responded decisively to Ottoman officials’ persistent overtures regarding a prospective commerce and friendship treaty. President John Quincy Adams formally commissioned regional representatives William Montgomery Crane, the Mediterranean fleet commander, and David Offley as plenipotentiaries authorized to negotiate, establish, and formalize trade agreements between both nations (see Figure 3) (Avcı 2016, p. 230). The President conveyed these appointments through confidential, specialized directives dispatched to both commissioners on 21 July 1828 (NARA 1828c, July 21, pp. 93–97). Within these instructions, President Adams—drawing upon Offley’s previous diplomatic correspondence—interpreted Ottoman enthusiasm for a treaty as a strategic opportunity to advance American interests and secure critical Black Sea access rights. The fundamental objective involved establishing permanent diplomatic and commercial relations between the United States and Ottoman Empire while guaranteeing American vessels unrestricted Black Sea navigation privileges. The American negotiating position consistently emphasized that vessels, citizens, and subjects from both nations must receive reciprocal “most favored nation” status within each other’s ports and territories—an essential treaty provision from the American perspective (Gordon 2015). Presidential instructions directed Offley to proceed independently to Constantinople for preliminary assessment of negotiating conditions with Ottoman authorities while avoiding British ministerial suspicion (The Massachusetts Spy Gazette 1830, p. 2). Adams mandated strict negotiation confidentiality with all correspondence transmitted directly to presidential review. Captain Crane received financial authority, with a $20,000 allocation for diplomatic expenses. Edward Wyer was designated negotiation secretary and appointed official treaty document courier. Finally, presidential instructions emphasized expeditious conclusion of negotiations with prompt Senate notification regarding outcomes (NARA 1828c, July 21, pp. 93–97). Despite Captain Crane and Mr. Offley’s negotiations achieving substantial diplomatic progress across numerous areas, they ultimately failed to produce a ratified agreement. Ottoman archival sources explicitly document imperial wariness toward British intentions. Contemporary strategic assessments recommended temporarily delaying and deflecting American diplomatic initiatives until British attitudes and potential responses could be thoroughly evaluated—an approach deemed appropriate given prevailing geopolitical circumstances (BOA, HAT, 1828). Nevertheless, these discussions enhanced mutual understanding while resolving significant obstacles impeding bilateral relationship development. Evidence clearly indicates the American administration had finally approached its long-sought strategic trade agreement, demonstrating unwavering commitment toward achieving this diplomatic objective (Avcı 2016, pp. 235–37).

Figure 3.

Document of approval of the appointment of William Montgomery Crane and David Offley by President John Quincy Adams. (Source: NARA, FM 77 Roll 162, p. 93).

Although Ottoman–American negotiations approached treaty finalization, they failed to achieve conclusive results. David Offley’s unyielding insistence on most-favored-nation privileges significantly contributed to a diplomatic impasse, as Ottoman officials-maintained reservations regarding such extensive concessions (Erhan 2001, pp. 103–13). Following negotiations that stalled specifically on this critical provision, President Andrew Jackson formally commissioned a new negotiating team on 12 September 1829, comprising the commander of the Mediterranean fleet Commodore James Biddle, David Offley, and Charles Rhind—appointed as American commercial and diplomatic representative to the Ottoman court (NARA 1829b, September 12, pp. 202–3). Influential newspaper Richmond Enquirer extensively analyzed Rhind’s appointment, noting his extended residence within Ottoman territories, widespread recognition among merchant communities, established trustworthiness concerning his regional expertise, comprehensive understanding of Turkish cultural and political characteristics, and the administration’s judicious selection of this representative (Richmond Enquirer 1830, p. 2). After a thorough examination of Offley’s negotiation reports, the administration concluded that reconstituting the diplomatic delegation would enhance negotiating prospects, thus incorporating Rhind into the commission. The government explicitly acknowledged Offley’s strict adherence to American instructions regarding most-favored-nation status—the specific provision prompting Ottoman reluctance toward treaty completion. Presidential instructions unequivocally directed the newly appointed delegation to maintain most-favored-nation status as a non-negotiable component in any prospective agreement. Jackson’s administration recognized European powers’ considerable influence over Ottoman policy and anticipated potential interference with American commercial interests (Adams 2007, pp. 80–100). Nevertheless, the administration observed no inherent Ottoman hostility toward American interests and noted apparent Ottoman willingness to establish permanent commercial arrangements. Presidential instructions emphasized conducting negotiations within respectful, amicable parameters while requiring both Biddle and Offley’s presence during formal discussions. The directive acknowledged potential Ottoman diplomatic sensitivities warranting appropriate consideration during negotiations (NARA 1829a, September 12, pp. 196–202). American diplomatic persistence regarding most-favored-nation provisions demonstrated unwavering commitment to this principle throughout treaty discussions. While maintaining cautious, strategic approaches during negotiations—recognizing European influence over Ottoman diplomatic positions—the United States exhibited procedural flexibility but refused substantive compromise regarding most-favored-nation status and fundamental commercial principles. This resolute insistence upon explicit most-favored-nation treaty provisions constitutes compelling evidence of ambitious American commercial aspirations throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea regions (Van der Lippe 1993, pp. 31–63).

Following protracted negotiations between James Biddle, David Offley, Charles Rhind, and Ottoman representatives, approximately eight months after their presidential commission, a historic friendship and commerce treaty was finally concluded on 7 May 1830. America’s persistent diplomatic initiatives ultimately achieved success (NARA 1831b, March 19, pp. 208–11). Contemporary accounts emphasized Rhind’s exceptional diplomatic acumen and regional expertise as decisive factors facilitating agreement finalization (Richmond Enquirer 1830, p. 2). The negotiations proceeded with such extraordinary confidentiality that even Rhind’s close associates remained unaware of his involvement in these sensitive discussions. Initially pessimistic American officials and merchants experienced simultaneous astonishment and elation upon receiving Rhind’s confirmation of treaty conclusion (Virginia Advocate 1830, p. 2). American newspapers reported that the treaty secured unrestricted Black Sea navigation rights for United States vessels, including unimpeded passage privileges, while establishing most-favored-nation status for American commerce throughout Ottoman territories. The agreement effectively eliminated longstanding American exclusion from Black Sea trade and terminated financial losses previously incurred through third-party intermediaries. Reports noted that the American administration had successfully achieved its strategic objectives through sustained diplomatic engagement (Stavridis 2024). Contemporary media characterized Sultan Mahmud II as strongly supportive of bilateral relations with genuinely amicable sentiments, emphasizing American national responsibility and self-interest in maintaining these favorable diplomatic conditions. News outlets further observed that positive diplomatic developments resulting from this treaty would consequently enhance American–Russian relations (Richmond Enquirer 1830, p. 2; Virginia Advocate 1830, p. 2).

The United States successfully incorporated strategically vital provisions into the final treaty. A confidential diplomatic communication dispatched to Nicholas Navoni, the State Department’s Istanbul representative, dated April 15, 1831, confirmed Senate ratification and presidential approval of the Ottoman–American commercial treaty (NARA 1831b, March 19, pp. 208–11). This correspondence instructed Navoni to formally notify Ottoman foreign ministry officials regarding American ratification, the imminent arrival of a newly appointed ambassador to Constantinople, and his forthcoming presentation of official ratification documents. Concurrent correspondence detailed David Porter’s appointment as America’s new Constantinople ambassador, outlining his diplomatic responsibilities. The most significant element within Porter’s instructions revealed the Senate’s rejection of a secret supplementary article appended to the commercial treaty, while approving all remaining provisions. It has been suggested that Charles Rhind suggested this secret article (Erhan 1998, pp. 459–61). This rejection primarily stemmed from apprehensions that this article might be interpreted as obligating American naval construction and timber provisions to Ottoman authorities. Additional concerns involved potential Ottoman coercion of American citizens into contractual shipbuilding arrangements. Porter received explicit instructions to clarify to Ottoman officials their retained rights to commission vessels within American shipyards (NARA 1831a, April 15, p. 211). This diplomatic exchange inaugurated an unprecedented era in Ottoman–American relations. Through the extensive privileges secured by American negotiators, United States commercial interests expanded significantly throughout regional markets, establishing America among the most commercially advantaged foreign powers throughout Ottoman territories.

4. Conclusions

This study has provided a comprehensive examination of Ottoman–American trade negotiation initiatives, drawing upon American primary sources. The diplomatic process culminating in the 1830 commercial treaty emerged through a complex interplay of economic imperatives, military considerations, political dynamics, and diplomatic strategies. The nascent United States’ strategic interest in Ottoman commerce served multiple objectives: expanding commercial opportunities, advancing economic development, and strengthening American regional influence. These initiatives progressed gradually due to multiple obstacles: attacks by Barbary corsairs, interference from European powers including Britain and France, Ottoman administrative hesitations, and internal Ottoman political complications.

American representatives dispatched to the region played a significant role in improving relations, and their confidential intelligence reports prepared the groundwork for ensuring that the 1830 treaty was signed in line with American objectives. This agreement inaugurated a transformative chapter in Ottoman–American relations, securing American Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea commercial interests while establishing the foundations for America’s economic expansion and long-term diplomatic sustainability. Today, the United States continues to pursue an active policy in the region, with objectives focused on energy security, maritime trade, and balancing Russia’s influence. Particularly, disagreements between regional states regarding energy resources and maritime jurisdictions in the Eastern Mediterranean have led to an increase in American influence in these areas.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. All publicly available databases are listed in the bibliography.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | It is a comprehensive and reliable digital archive made available by the USA government on 13 June 2013. The collection contains a plethora of documents, amounting to over 200,000, from the founding fathers, including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison. The documents have been meticulously compiled from original manuscripts and primary printed sources in the Library of Congress, NARA, and various university archives. (https://founders.archives.gov). |

| 2 | National Archives and Records Administration. The main basis of this archive is FM 77 ROLL 162 (Diplomatic Instructions of the Department of State 1801–1906, Volume 1). This roll contains diplomatic correspondence of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs spanning the period from 2 April 1823 to 9 July 1859. It also includes important letters prior to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and Ottoman Empire between 1820 and 1828. (https://catalog.archives.gov). |

| 3 | John Rutledge, Jr. (1766–1819) was the son of John Rutledge (1739–1800), a prominent statesman who served as Governor of South Carolina, Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court during the nation’s formative period. For further details, see (Cometti 1947, pp. 186–11). |

| 4 | Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (Prime Ministry Ottoman Archives) |

| 5 | Hatt-ı Hümayûn. In the context of Ottoman diplomacy, documents bearing the Sultan’s handwritten remarks are designated as “Hatt-ı Hümayûn” with certain exceptions. Authorship of these documents is attributed either to the Sultan himself or to individuals acting on his behalf, such as clerks. Hatt-ı Hümayûn constitute significant primary sources for understanding the perspectives and decision-making processes of the empire’s highest-ranking administrators. |

| 6 | Luther Bradish served as an American agent in Ottoman territories between 1820 and 1826, operating under the guise of an ordinary citizen. He established contact with Ottoman officials and conducted unofficial negotiations on behalf of the United States government. For further details, see (Luther Bradish Papers 1801–1863). |

| 7 | George Bethune English (1787–1828) was an American adventurer, diplomat, soldier, and author. For further details, see (Covey 2014, pp. 90–158). |

References

- 1801–1863, Luther Bradish Papers, MS 71. New York: New-York Historical Society, Call Number: MS 71, Date: 1801–1863.

- Adams, Thomas J. 2007. American Foreign Policy and the Ottoman State, 1774–1837, as Revealed in United States Documents. Master’s thesis, California State University, Sacramento, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Alrefae, Wael M. 2024. The Policy of the United States of America towards the Ottoman Empire 1830–1932 AD. South Eastern European Journal of Public Health 25: 1768–73. [Google Scholar]

- Andrianis, Demetrios C. 2021. Master Gunner George Marshall U.S.N. Digital Academic Research Archives, May 31, p. 21. Available online: https://www.demetrimusic.com/archive/marshall.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Avcı, Ayşegül. 2016. Yankee Levantine: David Offley and Ottoman–American Relations in the Early Nineteenth Century. Ph.D. thesis, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey. 332. [Google Scholar]

- BOA. 1820. HAT, no. 1236/48102, H-29-Z-1235, October 7. [Google Scholar]

- BOA. 1821. HAT, no. 1213, folder. 47507 (H-29-Z-1236/27 September 1821). [Google Scholar]

- BOA. 1827. HAT, no. 1203, folder. 47262B (H-10-Ca-1243/29 November 1827); Prime Ministry Ottoman Archives (BOA), Document Type (Hatt-ı Hümayun (HAT)), File No: 1236, Folder No: 48102, Date: 29 Z 1235, November 29. [Google Scholar]

- BOA. 1828. HAT, no. 1212, folder. 47490 (H-29-Z-1243/12 July 1828). [Google Scholar]

- Breitman, Ilana. n.d. The Forgotten Founding Father of America: The Barbary Conflicts, Part II: Navy and Commerce, 1776–1816. London: AP U.S. History.

- Carriero, Rich. 2008. Barbary Wars. Time Out Istanbul, July 12. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Kyle C. 2013. The Evolution of Ottoman Diplomatic Tactics from 1821 to 1840. Bachelor’s thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran. 1828. The Battle of Navarin. Phenix Gazette 4: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cometti, Elizabeth. 1947. John Rutledge, Jr., Federalist. Journal of Southern History 13: 186–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covey, Eric D. 2014. US Mercenary Encounters with the Ottoman World, 1805–1882. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, YX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Erhan, Çağrı. 1998. 1830 Osmanlı-Amerikan Antlaşması’nın Gizli Maddesi ve Sonuçları. Belleten 62: 457–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhan, Çağrı. 2000. Osmanlı-Amerikan Siyasi İlişkileri (1776–1917). Ph.D. thesis, Hacettepe University Institute of Social Sciences, Ankara, Turkie. [Google Scholar]

- Erhan, Çağrı. 2001. Türk-Amerikan İlişkilerinin Tarihsel Kökenleri. Ankara: İmge Kitabevi. 421p. [Google Scholar]

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1783a. Report on Letters from the American Ministers in Europe. December 20. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-06-02-0318 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1783b. The American Peace Commissioners to Elias Boudinot. September 10. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-40-02-0380 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1783c. To Benjamin Franklin from [Jean-Antoine?] Salva. April 1. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-39-02-0255 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1783d. To Benjamin Franklin from Pitot Duhellés and Other Consulship Seekers. January 28. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-39-02-0033 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1784a. Editorial Note: Reports on Mediterranean Trade and Algerine Captives. November 11. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-18-02-0139-0001 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1784b. Instructions to the American Commissioners, May–June 1784. May 7. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-16-02-0105 (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1786a. Enclosure I: P. R. Randall to His Father. April 2. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-09-02-0430 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1786b. From John Adams to the Marquis de Lafayette. June 26. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-18-02-0190 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1786c. John Lamb to the American Commissioners. May 20. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-18-02-0157 (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1788. From Thomas Jefferson to John Rutledge, Jr. June 19. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-13-02-0172 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1789. To George Washington from William Tate. August 3. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-03-02-0218 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1790. I. A Proposal to Use Force Against the Barbary States. July 12. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-18-02-0139-0002 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1796. To George Washington from Timothy Pickering. July 27. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-20-02-0323 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1799a. From John Adams to United States Senate. February 8. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-3329 (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1799b. To George Washington from Timothy Pickering. February 8. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0262 (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1801a. To Thomas Jefferson from Hammuda Pasha, Bey of Tunis. April 15. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-33-02-0512 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1801b. From Thomas Jefferson to Yusuf Qaramanli, Pasha and Bey of Tripoli. May 21. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-34-02-0122 (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1802. To James Madison from William Eaton. 20. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/02-04-02-0228 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1803. To James Madison from Thomas Appleton. October 7. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/02-05-02-0511 (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1804a. To James Madison from Levett Harris. June 29. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/02-07-02-0402 (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Founders Online, National Archives. 1804b. To James Madison from Thomas Appleton. May 26. Available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/02-07-02-0263 (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Geyikdağı, Necla V. 2011. French Direct Investments in the Ottoman Empire Before World War I. Enterprise & Society 12: 525–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gordon, Leland J. 2015. American Relations with Turkey, 1830–1930: An Economic Interpretation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzidimitriou, Constantine G. 2002. Founded on Freedom and Virtue: Documents Illustrating the Impact in the United States of the Greek War of Independence, 1821–1829. Scarsdale: Aristide D. Caratzas. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Harry N. 1976. The Bicentennial in American-Turkish Relations. Middle East Journal 30: 293. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, Ray W. 1931. The Diplomatic Relations of the United States with the Barbary Powers: 1776–816. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jewett, Thomas. 2002. Terrorism in Early America: The U.S. Wages War against the Barbary States to End International Blackmail and Terrorism. The Early America Review 4: 1. Available online: http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2002_winter_spring/terrorism.html (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Kara, Adem. 2014. Osmanlı Devleti—A.B.D. Ticari İlişkileri. Akademik İncelemeler Dergisi 1: 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Gülşah. 2024. 19. Yüzyıl Sonlarında İstanbul’un Ticari Durumu (Amerikan Konsolosluk Raporlarına Göre). History Studies 16: 319–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaoğlu, Barin. 2021. Turkey-United States Relations. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kayapınar, Selda. 2017. 1830 Osmanlı-ABD Ticaret Antlaşması Öncesi Amerika’nın Diplomasi Girişimleri. Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 51: 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- King, Charles. 2004. The Black Sea: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalskyi, Stanislav. 2020. The Stages of the US Mediterranean Policy’s Development in the 19th Century: Geopolitical Outlines and Economic Interests. Kyiv: Kyiv National University, pp. 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Köprülü, Orhan F. 1987. Tarihte Türk-Amerikan Münasebetleri. Belleten 51: 927–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Frank. 2005. The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World. London: Macmillan, p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Mantran, Robert. 1995. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu Tarihi II (XIX. Yüzyılın Başlarından Yıkılışa). Translated by Server Tanilli and Cem Yayınevi. İstanbul, Türkiye, p. 499. [Google Scholar]

- Marzagalli, Silvia. 2010. American Shipping into the Mediterranean during the French Wars: A First Approach. Research in Maritime History 44: 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- McCusker, John J. 2010. Worth a War? The Importance of the Trade between British America and the Mediterranean. In Rough Waters: American Involvement with the Mediterranean in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Edited by Silvia Marzagalli, James R. Sofka and John J. McCusker. Research in Maritime History. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, Robert. 2018. The Young U.S. Navy Battled North African Pirates. January 10. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/young-u-s-navy-battled-north-african-pirates-1773650 (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- NARA. 1820a. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State. Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. April 15, p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1820b. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. December 20, pp. 177–95. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1823a. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. April 2, p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1823b. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. November 23, pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1823c. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. December 27, pp. 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1824. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. May 14, pp. 104–6. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1825a. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. February 7, pp. 108–9. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1825b. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. February 7, p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1825c. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. January 3, p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1825d. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. September 6, pp. 110–11. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1825e. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. September 28, pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1825f. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. November 30, pp. 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1826. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. July 19, pp. 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1827. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. November 26, pp. 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1828a. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. February 17, pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1828b. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. January 24, pp. 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1828c. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. July 21, pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1829a. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. September 12, pp. 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1829b. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. September 12, pp. 202–3. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1831a. FM 77 Roll 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. April 15, p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- NARA. 1831b. FM 77 Rol 162. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, Diplomatic Instructions 1785–1906. March 19, pp. 208–11. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, Phillip C. 2016. Algiers, Ottoman Regency of. In The Encyclopedia of Empire. Edited by Nigel R. Dalzieland and John MacDonald MacKenzie. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Ozavci, Ozan. 2023. The Ottoman Imperial Gaze: The Greek Revolution of 1821–1832 and a New History of the Eastern Question. Journal of Modern European History 21: 222–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örmeci, Ozan, and Hüseyin Işıksal, eds. 2020. Historical Examinations and Current Issues in Turkish-American Relations. Berlin: Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Payaslian, Simon. 2005. The Political Economy of U.S. Foreign Policy toward the Ottoman Empire and the Armenian Question. In United States Policy toward the Armenian Question and the Armenian Genocide. Edited by Simon Payaslian. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Peskin, Lawrence A. 2009. Captives and Countrymen: Barbary Slavery and the American Public, 1785–1816. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. vii + 256. [Google Scholar]

- Phenix Gazette. 1828. From Europe. Phenix Gazette 4: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond Enquirer. 1830. Treaty with Turkey. Richmond Enquirer 27: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Gene A. 2006. Review of The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World, by Frank Lambert. The Journal of Military History 70: 509–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavridis, Stavros. 2024. The United States and Ottoman Navy in the 1830s. The National Herald. July 28. Available online: https://www.thenationalherald.com/the-united-states-and-ottoman-navy-in-the-1830s/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- The Massachusetts Spy Gazette. 1830. Treaty with Turkey. The Massachusetts Spy Gazette 59: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lippe, John M. 1993. The ’Other’ Lausanne Treaty of Lausanne: The American Public and Official Debate on Turkish-American Relations. The Turkish Yearbook of International Relations 23: 31–63. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Advocate. 1830. Treaty with Turkey. Virginia Advocate 4: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Vivian, Cassandra. 2015. Luther Bradish: American Agent on the Nile. Academia.edu. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/24287953/Luther_Bradish_American_Agent_on_the_Nile (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Yılmaz, Şuhnaz. 2015. Turkish-American Relations, 1800–1952: Between the Stars, Stripes and the Crescent. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).