Abstract

Ludwig Edinger (1855–1918) is often perceived as a functional neuroanatomist who primarily followed traditional lines of microscopic research. That he was a rather fascinating innovator in the history of neurology at the turn from the nineteenth to the twentieth century has, however, gone quite unnoticed. Edinger’s career and his pronounced hopes for future investigative progress in neurological work mark an important shift, one away from traditional research styles connected to department-based approaches towards a multi-perspective and quite advanced form of interdisciplinary scientific work. Being conceptually influenced by the Austrian neuroanatomist Heinrich Obersteiner (1847–1922) and his foundation of the Neurological Institute in Vienna in 1882, Edinger established a multi-faceted brain research program. It was linked to an institutional setting of laboratory analysis and clinical research that paved the way for a new type of interdisciplinarity. After completion of his medical training, which brought him in working relationships with illustrious clinicians such as Friedrich von Recklinghausen (1810–1879) and Adolf Kussmaul (1822–1902), Edinger settled in 1883 as one of the first clinically working neurologists in the German city of Frankfurt/Main. Here, he began to collaborate with the neuropathologist Carl Weigert (1845–1904), who worked at the independent research institute of the Senckenbergische Anatomie. Since 1902, Edinger came to organize the anatomical collections and equipment for a new brain research laboratory in the recently constructed Senckenbergische Pathologie. It was later renamed the “Neurological Institute”, and became an early interdisciplinary working place for the study of the human nervous system in its comparative, morphological, experimental, and clinical dimensions. Even after Edinger’s death and under the austere circumstances of the Weimar Period, altogether three serviceable divisions continued with fruitful research activities in close alignment: the unit of comparative neurology, the unit of neuropsychology and neuropathology (headed by holist neurologist Kurt Goldstein, 1865–1965), and an associated unit of paleoneurology (chaired by Ludwig Edinger’s daughter Tilly, 1897–1967, who later became a pioneering neuropaleontologist at Harvard University). It was especially the close vicinity of the clinic that attracted Edinger’s attention and led him to conceive a successful model of neurological research, joining together different scientific perspectives in a unique and visibly modern form.

1. Introduction

Research institutes, along with the scientists, experimental systems, and economic resources connected to such places of scientific inquiry, cannot be considered as isolated from the world beyond their physical walls (Lenoir 1997, pp. 1–21; Rheinberger 1997, pp. 28–31). They are intricately related to broader social developments, economic dynamics, and the technological transformations of the places and cities in which they can be found and analytically positioned (cf. Dierig et al. 2003; Dierig 2000). Scientific urban centers are often not only buzzing cultural places, but likewise centers of innovation and the construction of new experimental and observational knowledge. This is most obvious in the case of the early establishment of Ludwig Edinger’s Neurological Institute in Frankfurt am Main, during dynamic and far-reaching transformations that took place in this bourgeois city in fin de siècle-Germany (Hammerstein 2000, pp. 14–24; Stahnisch 2020, pp. 96–102). Using the example of Edinger’s Institute, this article scrutinizes the organizational and knowledge interchanges between the city’s culture, its social and scientific networks, along with the experimental and clinical research programs of this outstanding German neuroanatomist and his scientific collaborators (Krücke 1963, pp. 9–14). Several constitutive factors of the organizational set-up of this center for advanced neuroscientific research1 shall be analyzed here and put in the historical context of urbanization and the bourgeois culture of the city, before the Frankfurt institutions were formally established as a separate university institution just before the outbreak of World War One (Benzenhöfer and Kreft 1997, pp. 31–35).

The major shift in the scientific career of Ludwig Edinger (1855–1918), who was born into a German-Jewish family in nineteenth-century Worms, can best be traced back to the point when he turned to the culturally rich atmosphere of the city of Frankfurt, which served his basic intellectual and scientific needs so well (Emisch 1991, pp. 56–78). He settled there as one of the first clinically working neurologists (“Nervenärzte”) in 1883 and soon developed his private clinic, in conjunction with the outpatient department of the “city hospital Sachsenhausen”, into one of the most thriving research institutions of the time (Kreft 2005, pp. 226–30).2 This is most remarkable, since the development of Edinger’s Institute really took place in a mercantile city that previously had not had a university or higher education institution; it was primarily dependent on entrenched local traditions of citizen pride, individual ingenuity, and Jewish philanthropy.

The role of the city, its bourgeois culture, and technoscientific developments of the Wilhelminian Era will thus be examined here as to their influence on Edinger’s institute and work in the “medical republic of Frankfurt” (Mann 1972, p. 244). However, the results of this institution cannot be exclusively reduced to the work of one individual alone but need to take other municipal actors into account as well (Roth 1996, p. 586), while the title of this article might suggest such a view. To the contrary, a closer look at the life and work of Ludwig Edinger reveals many facets of how interdisciplinary work and scientific collaboration may be organized and sustained for longer periods of time. It should be added that this even extended to such sociocultural surroundings that were not always in favor of the activities of a maker and shaper of modern neuroscience like him. As can be gleaned from Edinger’s biography, the academic situation at the end of the nineteenth century proved time and again to be a stern hindrance to the accomplishments and intellectual excellence of Jewish neuroscientists, who tried to find their place in one of the research niches in medicine—such as neurology, psychiatry, pediatrics, dermatology, and neuropathology—in the frequently anti-Semitic academic context of the time (Eulner 1970, pp. 257–82; Kreft 2005, pp. 122–34).

2. Conceptual Endeavors and Contemporary Discourse

Edinger’s conceptual endeavors and his attempts to undercut nineteenth-century styles of research in his laboratory at the Senckenberg Institution (and later in his own Neurological Institute) may be adequately characterized through the notion of a new “research school” in the contemporary scientific context:3

At a less immediately cognitive level, a successful research school depends upon a readily available pool of talented potential recruits (a condition that presumably works to the advantage of university-based schools), and upon the director’s capacity to inspire loyalty, social cohesion, and ésprit de corps among his students. To produce a school that extends beyond himself, the director must nurture early independence, self-reliance, and ambition among his students, especially by encouraging them to publish under their own names at an early stage of their career—even if and when the director has contributed importantly to the published research. Toward this end it is important that the school have easy access to (or, better still, control over) publication outlets for the work of its younger members. When their training is completed, students who have already published will have enhanced their candidacy for positions elsewhere, and if the director has ‘placement power’ in his discipline he can do much to ensure their employment in a propitious academic setting, thereby further extending the reputation and influence of his school. Finally, to achieve sustained success, the director must have or must quickly acquire sufficient power in the local and national institutional setting to secure adequate financial support and an institutionalized commitment to his enterprise.(Geison 1981, p. 26)

Thus, we may see how Edinger was successful in not only bringing together people from very different research areas, such as neuroanatomy, neuropathology, and clinical neurology, but also in founding and securing interdisciplinary exchanges of knowledge, materials, pupils, and so forth. Taking this historiographical perspective as the theoretical vantage point of this article, one may realize how Edinger arrived at his many pioneering contributions to contemporary neuroscientific work, which have already been noted and identified in the existing scholarship (e.g., Stahnisch 2003, pp. 9–13; Prithishkhumar 2012; Patton 2015).

Now, in the 110th year of the incorporation of Edinger’s Institute into the bourgeois University of Frankfurt, some more genuine perspectives on the organizational and political contributions to contemporary neuroanatomy can be worked out (see also in: Eling 2018) and put in the social and cultural context of their time (e.g., Emisch 1992, pp. 311–17). In order to be able to do this, a brief exploration of existing conceptual approaches on interdisciplinarity in the sciences appears necessary. Unfortunately, not many historical working definitions of how “interdisciplinary research” is characterized are readily available—especially with regard to the historiography of medicine and the life sciences (Adelman 2010, pp. 17–20; Lenoir 1993, pp. 70–102). The neurosciences are no exception in this methodological regard. Conversely, historiographical aspects of each of the involved disciplines—neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, neuropathology, psychology, and clinical medicine, etc.—can be found and have been examined in separate approaches to these scientific specialties (e.g., Peiffer 1998; Nicolas and Ferrand 1999; Borck 2005; Karenberg 2006; Stahnisch 2012). However, when broader research units are scrutinized, such as research programs, neuroscience centers, or interdisciplinary institutes, it is not straightforward to find good methodological tools that guarantee adequate assessments of the methodological characteristics and elements. For example, research in Science and Technology Studies has primarily focused on the physical sciences (e.g., in Trevor Pinch’s work on early physics and chemistry and Karin Knorr-Cetina’s investigations on particle physics), or Michel Collins’ publications on technical engineering (e.g., the laser industry) (e.g., Pinch 2009, pp. 85–100; Knorr-Cetina 1985, pp. 85–101; Collins 1974, pp. 165–86), whereas accounts for interdisciplinarity in the historiography of biomedicine appear fairly underdeveloped, probably with the exception of such scholars as William Bechtel (experimental physiology), Frederick G. Worden (neuroscience in the twentieth century), and Toby Appel (American biological research) (Bechtel 2001, pp. 81–101; Worden et al. 1975, p. 545; Appel 1988, pp. 207–30). As a point to embark on the analysis, some theoretical considerations of the German and Swiss philosophers of science Rudolf Kötter and Philipp Balsiger from their 1999 article “Interdisciplinarity and Transdicsiplinarity: A Constant Challenge to the Sciences” appear quite useful to tackle the historical problem at hand:

It is occasionally mentioned that there is no need for the tentative introduction of the term “interdisciplinarity”. It is claimed that a “pragmatic” use of the term is enough, because even the term disciplinarity is not very well defined […]. This is not the opinion of the authors of this paper. Even if it is claimed that the development of disciplines does not really follow the criteria which are used in the philosophy of science but follows rather the criteria of the general history of culture and facts in the history of institutions (both seem to display a “pragmatic” element), this doesn’t mean that forms of collaboration between factually and institutionally determined disciplines cannot be described more accurately. As far as the terminological concept […] is concerned, it is decisive to emphasize the potential of both theoretical and methodological, as well as the practical and organizational problems related to the form of interdisciplinarity.(Kötter and Balsiger 1999, p. 102)

Although Kötter’s and Balsiger’s current interpretation of the concept of “interdisciplinarity” and their emphasis on the empirical investigation of its meanings in actual scientific practices is helpful for illuminating some historical problems regarding the dissolution of disciplinary boarders in the emerging field of the neurosciences, the perspective of concern here is rather the history of science than the philosophy of science: What did early neuroanatomists, like Ludwig Edinger, themselves think about interdisciplinarity? How did they anticipate the ways it would affect their research orientation? And how were they creating certain organizational models that met their research aims? Answering these questions will inform current day understanding as to how neuroscientific and neuropathological concepts came into being (Strösser 1993), and how they were restricted through political, cultural, and economic factors. Thus, in focusing on Edinger’s Frankfurt institute, the current article seeks answers as to how far the set-up of specific institutes could serve as a valuable cognitive foundation of research programs in the neurosciences. As American historian of science William Coleman once noted:

[…] what is involved is the restoration or even introduction of comprehensive and exact historical research within the framework of sociology or, less formally construed, of social relations of science; the need is to see “knowledge itself as a central element in shaping the structure of disciplinary cultures and subcultures”.(Coleman 1985, p. 49)

3. On Edinger’s Biographical Background

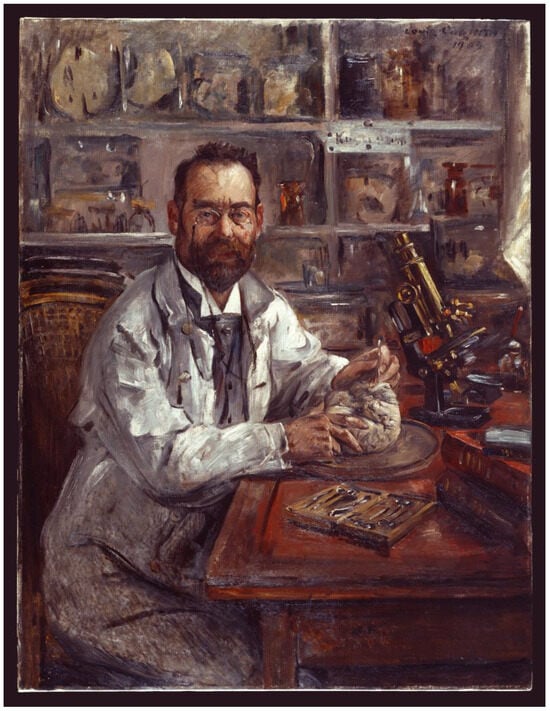

Ludwig Edinger (see Figure 1) was born in the (Rhine-)Hessian city of Worms and studied medicine at Ruprecht-Karls University in Heidelberg from 1872 to 1874, where the comparative morphologist Carl Gegenbaur (1826–1903) was his anatomy teacher, whom he had welcomed enthusiastically as the friend and coworker of the prominent natural historian Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) at Jena (Kreft 2005, pp. 171–75). Thereafter, he attended the Friedrich-Wilhelms University of Strasburg (from 1874 to 1877) and found supervision for his scientific M.D. thesis “On the Histology of the Mucosa of Fish and Some Remarks on the Phylogenesis of the Glands of the Small Intestine” (Germ., Edinger 1876) through the illustrious anatomist Wilhelm Waldeyer (1836–1921). Later, on 21 October 1874, Edinger remarked that, while he was working in Waldeyer’s tower laboratory over the Strasburg hospital entrance, he had the best introduction to microscopic methodology and understanding of the scientific rigor of observation (Edinger [1919] 2005, p. 61).

Figure 1.

Portrait of Ludwig Edinger by Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), 1909, original measurements: 145 cm (height) × 110 cm (width). Source: Historical Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany (CC-BY-SA 4.0, Historisches Museum Frankfurt (B.1956.01), Photo: Horst Ziegenfusz).4

Furthermore, his medical training also brought him into a close working relationship with Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen (1833–1910), who had described the clinical symptoms and morphological signs of neurofibromatosis (“multiple neuroma”) in 1882 (Von Recklinghausen 1882) and became even more influenced by the young Adolf Kussmaul (1822–1902), who had come to Strasbourg in 1876 as professor for clinical medicine (Stahnisch 2016a, p. 233f.). Right after completing his military service in Worms and Strasburg, Edinger began his medical internship with Kussmaul, whom he admired for his broad therapeutic knowledge paired with a profound critical understanding of differential diagnosis in medicine. Decisive for many aspects of Edinger’s later scientific interests was his neurohistology service in Kussmaul’s clinic. As part of his laboratory service duties, Edinger, for example, had to investigate the pathological material of all brain tissue derived from Kussmaul’s clinical patients who had died while being hospitalized in the Strasburg Bürgerhospital. Without the help of closer training supervision, Edinger began to study neuropathology by himself with whatever book and manual he could lay his hands on—in a field that he recognized as having rudimentary microscopic technology and insufficient research literature available:

Histological dyes are still inadequate, and slides are not prepared any further than the frontal end of the pons, because “any understanding of the normal” ends at this point.(Edinger 1876, p. 685; author’s transl.)5

Yet what appeared as a moment of personal dissatisfaction during the Strasburg period later served as a valuable inspiration for him to change the course of neuroanatomical and neurological research. After three years, as was the custom of the time, Edinger was obliged to change his internship and decided to transition to the internist Franz Riegel (1843–1904) at the University of Gießen. At this Hessian university, he completed his Habilitation (~the second PhD) in 1881 with a thesis entitled “Inquiries into the Physiology and Pathology of the Stomach” (Germ., Edinger 1881). However, due to the rise of anti-Semitism at German universities at the time, his work on the second PhD was already threatened, so that he had to accelerate his research and writing, in order to complete his academic defence (Edinger [1919] 2005, p. 83). Edinger then used the first liberation from his clinical duties in order to participate in the regular meetings of some major medical and scientific societies, like the Society of German Natural Scientists and Medical Doctors (~Gesellschaft Deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte—Leopoldina), before commencing with a splendid European peregrination. It brought him to Sir William Richard Gowers (1845–1915) at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic in London, England (Toodayan 2016, pp. 62–4), then to microbiologist Robert Koch (1843–1910) and psychiatrist Carl Friedrich Otto Westphal (1833–1890) in Berlin, before receiving further postgraduate training with Carl Weigert (1845–1904), Paul Flechsig (1847–1929), and Wilhelm Heinrich Erb (1840–1921) at the University of Leipzig (Angermann and Steinberg 2005, pp. 252–8). In 1883, Edinger also went to Paris, France, to spend some time in Jean-Martin Charcot’s (1825–1893) leading neurological clinic at the Salpêtrière (Koehler 2013, pp. 93–6), before moving to Frankfurt.

Until this point in time, nothing really spectacular had happened in Edinger’s biography and career; and it might even be speculated whether we would be as interested in his work and biography if major shifts had not brought him into the cultural atmosphere of the bourgeois city of Frankfurt (Siefert 2001, pp. 20–5), which came to serve his basic intellectual and scientific needs very well. Because Edinger was born into a Jewish family, his plans to work as a medical practitioner in this city and give additional lectures at the nearby University of Gießen were suddenly interrupted when the university rector did not allow him to execute his Venia legendi lecturing rights (Kreuter 1996, p. 75). Although German universities had experienced some confessional openings since the end of the 1870s, it was not uncommon, especially in the smaller and more traditional universities, that Jewish academics were thwarted from pursuing their academic careers (Stahnisch 2010a, p. 20f). Edinger was hereafter forced to settle as one of the early clinically active neurologists in private practice in the city and thus made a virtue out of sheer necessity by developing a research surrounding that could serve his needs for the scientific study of the brain. His neurological practice was set up in downtown Frankfurt in 1883 in the Stiftstraße Nr. 30, which later developed into the outpatient department of the city hospital Sachsenhausen. It was with great luck that he could eventually realize his scientific plans with the Frankfurt Senckenberg Foundation, which approved him as a full member of this association (Kreft 2005, p. 226).6 Later, in 1885, Edinger also became a member of the local Ärztlicher Verein of physicians: The Senckenberg Society of Natural Scientists. His superbly fruitful working situation in this milieu was characterized by Edinger as follows:

All scientists who worked at the “Senckenberg” contributed to what could be called a small community. One felt directly at home in the collections, laboratories, and the library, the latter being easily accessible. Shortages were quickly handled, and requests were directly put through to a person who could answer them […]. Never before and never again did I find a society of people of such a pure spirit and goal-directedness. The Frankfurt doctors did receive me in a good spirit and helped me set up my private practice.(Edinger 1904, p. 34; author’s transl.)

However, Edinger’s astonishment at finding such scientifically achieving and communally thinking medical practitioners in a city that had never had a university itself, referred to a local tradition of citizen pride and especially Jewish philanthropy as an important basis for many scientific and cultural activities. This also becomes apparent during the foundational steps towards the University of Frankfurt, since 1912, and is particularly present in Edinger’s own engagement to find private money for the foundation of the institute. Also, Edinger married the daughter of a Jewish Banker in Frankfurt and became very affluent himself (Kreft 2005, pp. 127–28).

Edinger’s statement that “never before and never again did I find a society of people of such a pure spirit and goal-directedness” may also be perceived as an important stimulus for the creation of his own institute in 1903; a plan that had already evolved since 1885 (Kreft 2005, p. 380, fn. 133). Although set up in the cramped surroundings of a single room in the Senckenberg Anatomy, his institute was entirely devoted to the study of neurology and neuroanatomy from its very beginnings. Here, he tried to integrate the different aspects of neuroscientific research that he had experienced in Strasburg, Berlin, Leipzig, and Paris before. Quite often in his correspondence and autobiographical notes, Edinger also drew comparisons with Flechsig’s application of Weigert’s myelin-stain or Charcot’s clinical observations in neurological patients, while his institute was originally set up as a single working place in Weigert´s Senckenberg Anatomy (Edinger [1919] 2005, pp. 60–2).

4. The Institute

Edinger’s first years in Frankfurt were quite challenging, though they proved to be not unsuccessful scientifically:

Everything that I needed was not very easy to get. There was no working place for histological investigations in the Anatomy itself and I had no instruments, other than a small microscope that I already bought in 1872. […] I may, nevertheless, take the credit for my scientific optimism when overcoming all possible obstacles after some time. In my private bedroom, an old cupboard was installed […] together with a microscope table with doors and drawers. Old saucers, glasses, and whatever I could find in my mother’s household, to serve my needs, was taken away and reinstalled in the new home. Further, I wrote to Professor [Johann Friedrich] Ahlfeld [1843–1923] the director of the Marburg university clinic of obstetrics to send all kinds of abortive material (“Früchte”). And he did send me a lot. It had always been a secret hustle and bustle when another box arrived by post and when I had to smuggle it into my flat without the knowledge of my landlord. […] I extirpated the brains with care, put them into preparation fluids and burned the heads in the oven, after having asked my landlord to leave the house for whatever reason I could find.(Edinger 1886, p. 3; author’s transl.)

Such were the working conditions under which Edinger produced his relatively small but highly successful textbook Ten Lectures on the Fabric of the Nervous Central Organs (~Zehn Vorlesungen über den Bau der nervösen Zentralorgane) (Germ., Edinger 1885), which went through eight editions until 1911. It was due to the reputation of his textbook that Edinger was made an adjunct professor (außerplanmäßiger Professor) at the Senckenbergisches Institut in 1896. Relying on his firm relations with the local members of the Frankfurt medical community and together with his engaged and personal contributions, the neurohistologist Carl Weigert from the University of Leipzig could be won for Frankfurt—in 1885—as the new director of the Senckenbergische Anatomie (Edinger [1919] 2005, p. 104). There, they both worked closely together; so much so that in the end, Edinger could not tell whether research ideas were his own or belonged to Weigert (see Figure 2), or even somebody else (Riese and Goldstein 1950, p. 133).

Figure 2.

The research colleagues and collaborators of Ludwig Edinger at the Senckenberg department of anatomy in Frankfurt am Main, 1898. Carl Weigert, as the head of the Senckenberg Anatomie, is sitting as the second researcher at the bottom right (Emisch 1991, p. 74). The image is in the Public Domain.

As experimental neuroanatomist Paul Glees (1909–1999) wrote in his biographical entry to Hugo Freund’s and Alexander Berg’s History of Microscopy—based on his early personal experiences of the institute during the interwar period—in 1964: “Goldstein and Edinger invited their young collaborators regularly to their homes for discussions on a variety of neurological problems” (Glees 1964, p. 77).

There were many informal meetings and academic discussion circles in which Edinger participated or which he had himself initialized in the local communities in Frankfurt. Until Weigert’s death (in 1904) this led to an increased interaction with many collaborators within and outside the institute. These collaborators included the child psychiatrist Heinrich Hoffmann (1809–1894), the general pathologist Carl Friedländer (1847–1887), and the experimental physiologist Albrecht Bethe (1872–1954) in Frankfurt (Stahnisch 2016b, pp. 1–3). In his exchanges of anatomical specimens and scientific correspondence, also the neuroanatomist Adolf Wallenberg (1862–1949) from the University of Danzig frequently referred to Edinger and used to call the Frankfurt neuroanatomist his “anatomical conscience” (Edinger [1919] 2005, p. 190). Additionally, many students from America, England, The Netherlands, France, and Belgium, came to work with Edinger, such as neurologist Arthur van Gehuchten (1861–1914) from the Université Catholique de Louvain and later, after Edinger’s death, similar international visits continued with the institute’s successors, as in the case of influential neuroanatomist Paul Glees (e.g., Aubert 2010, p. 256f).

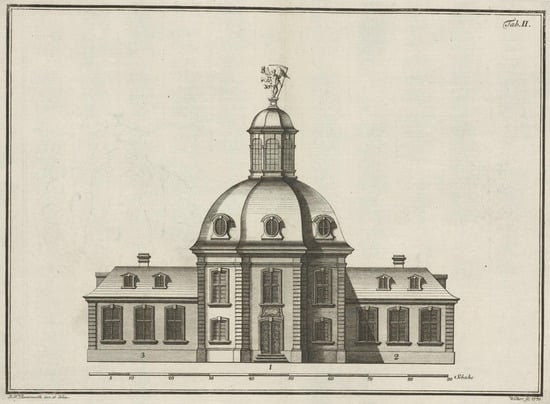

However, it took Edinger until 1903 when he finally could exchange his one-room laboratory that he had received from Weigert for an official department, being made the director of the new “Neurological Institute” in Frankfurt (Kümmel 1993, p. 279f). Since 1902, Edinger further organized the equipment of a new laboratory for neuroscience research in the recently reconstructed Senckenbergische Pathologie (see Figure 3), which then even became referred to as “Edinger’s Institute” (Hammerstein 2012, p. 45). It was to become an interdisciplinary workplace for the study of the nervous system in morphological, experimental, clinical, and comparative perspective (Edinger 1896), as the Edinger pupil and neurorehabilitation specialist Kurt Goldstein (1878–1965) remarked:

In Edinger I found an excellent interpreter of the great variations in the relationship of the structure of the nervous system to the behavior of animals, thus he created a new field of science “the comparative anatomy of the nervous system”.(Goldstein 1971, p. 4)

Figure 3.

Drawing of the old Anatomical Institute, which was to form part of the institutions and units in the architectural agglomeration, which supported medicine, research, and poor relief in the city of Frankfurt am Main. The image is taken from the endowment certificate of 1776. Courtesy of the University Collection and Archives, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Being conceptually influenced by the Austrian neuroanatomist Heinrich Obersteiner and his 1882 foundation of the “Neurological Institute” in Vienna (Bechmann 1999, pp. 8–31), as well as by Oskar (1870–1959) and Cécile Vogt’s (1875–1962) “Neurologische Centralstation” in Berlin (Stahnisch 2008, p. 79f), which became integrated into Friedrich-Wilhelms-University in 1902, Edinger established many scientific requirements and institutional settings that paved the way for new types of neuroscience research:

Draft.PROPOSAL SUBMISSION.From the Medical Faculty in Frankfurt a. MainRegardingthe necessary Reorganization of the Neurological Institute.The Neurological University Institute in Frankfurt a. Main is a foundation of Ludwig Edinger. It developed out of a small working place in the old Senckenberg Pathological Institute through the engagement of its founder into a research institute of world-renown. Since several years now, it has also been introduced into the international circle of research institutes in brain research. It has thus made a similar development as the Neurological Institute of [Constantin] v. Monakow [1853–1930] in Zurich and of [Heinrich] Obersteiner in Vienna. When the University of Frankfurt was founded, it became a crown jewel of all the research institutes that had been integrated into the organization of the university, after its founder [Edinger] had successfully secured continuous funding from the [Senckenberg] foundation.(Edinger Commission 1919, p. 1; author’s transl.)7

Following the long-winded planning process and development, the official consolidation phase emerged during the years immediately preceding the First World War, when the institute became one of the signing and initiating institutions that agreed, in 1912, to support the foundation of the new University of Frankfurt as a privately funded, philanthropic post-secondary institution (Kreft 2005, pp. 226–29). Consequently, in 1914, Edinger was made a Full Professor of Neurology at the university, having two basic research departments at his disposal: the anatomical and the pathological department. Furthermore, he could rely on his own practice in the Frankfurt outpatient clinic for nervous diseases (~Frankfurter Poliklinik für Nervenkranke) at the city hospital Sachsenhausen south of the Main River, which he led together with the internist Georg Dreyfus (1879–1957) (Heuer and Siegbert 1997, pp. 66–67). He also collaborated with the neurological clinic of the city hospital Haus Sommerhoff, which was run by the clinician August Knoblauch (1863–1919) since 1900 and was later outfitted as the Goldstein Institute for Research into the Consequences of Brain Injuries during the First World War (Stahnisch and Hoffmann 2010, pp. 297–99).

However, due to the war there was a decisive cut in funding to the newly inaugurated university, so that the incorporation of the outpatient clinic for nervous diseases into the university medical clinic could not be realized before Edinger’s death. Then, the so-called Villa Sommerhoff was approved by the university’s board of curators as the unit of neuropsychology and pathology, which had been led by Kurt Goldstein since 1914, who became later also supported through his assistant Walther Riese (1890–1974) since 1920. This intensive collaboration in neuropsychology further included individuals such as Favel Friedrich Kino (b. 1882), Hans Max Cohn (b. 1883?), and, of course, Adhémar Gelb (1887–1936), who contributed major advances to psychological patient testing (Simmel 1968, p. 9).

It is interesting to see that after Edinger’s death, the Faculty’s Edinger Commission had been much more occupied with the interdisciplinary legacy (~“Vermächtnis Edingers”) (Lewey 1970, p. 114), than with the fate of neuropathology at the institute alone. They fervently supported neuropathologist Walther Spielmeyer’s (1879–1935) application from the University of Munich, whom they regarded as the right person to handle the organizational challenges to expand the institute to altogether six research departments. However, the directorship of the institute had to be given to Kurt Goldstein—in 1918/19—when neither Spielmeyer nor Adolf Wallenberg from the University of Danzig accepted, since the inferior endowment did not allow contributing to the growth of its academic units (see also: Goldstein 1971, p. 7).

A next phase in the development of the institute started with the intensive negotiations after Edinger’s death in 1918, when six departments were planned. Of these, under the austere circumstances of the Weimar Republic, only three serviceable divisions emerged: neuropathology, neuroanatomy (inaugurated by Edinger himself as “comparative neuroanatomy”), and clinical neurology.8 These continued with fruitful research (Kreft 1997, pp. 134–36). After Kurt Goldstein had been made the new institute director, Karl Kleist (1879–1960) from the University of Rostock was hired and given the vacant chair for psychiatry, including clinical responsibilities and teaching obligations, which were newly distributed by giving both institutions equal autonomy (Neumärker and Bartsch 2003, pp. 411–58). The director of the neuroanatomical department was now the zoologist Victor Franz (1883–1950), and the director of the neuropathological department was Heinrich Vogt (1875–1957), who had both been Edinger’s long-term collaborators. Both continued their work during the Nazi period, when the institute was affiliated with the psychiatry clinic under Kleist from 1933 to 1937 and under Arnold Lauche (1890–1959) and the psychiatrist Gerd Peters (1906–1987), who was hired from the German Research Institute for Psychiatry (~Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Psychiatrie) from 1937 to 1945) (Kreutzberg 1987, pp. 82–85). As is well known, Kurt Goldstein—after a short period at the Berlin Moabit hospital—and Tilly Edinger—after losing her position due to the infamous “Law for the Re-Establishment of a Professional Civil Service” (Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums) during the Nazi period—both emigrated to the United States and recommenced their careers in their new host country, while holding onto many of their experiences and visions that were born and developed at the Edinger Institute (Stahnisch 2010b, p. 48, 57).

5. The Ground Level of Research—Results

In connecting the organizational set-up of Edinger’s institute in Frankfurt to the ground level of neuroscientific research with contemporary collaborators at the time, its later director from 1984 to 2000, neuroscientist Wolfgang Schlote (1932–2020), pointed out in several articles that the Frankfurt institute was an outstanding place for the investigation of the nervous system since its early inception (cf. Schlote 2002). First, there had been Edinger’s applications and further developments of Carl Weigert’s staining methods in many fields of neuroanatomy, which had led to the successful discovery of the Tractus spinothalamicus (already in 1885).9 Then there was also the discovery of the Nucleus accessorius nervi oculomotorii, later renamed after Edinger and Westphal, along with many comparative studies on neencephalization, which were to culminate in the pathological autopsies of Heinrich Vogt (1875–1957) of human brains, e.g., on children without a cerebrum (~Großhirn) (Vogt 1905). American neuroanatomist Charles Judson Herrick (1868–1960) even went so far as to note in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society:

These two men [Ludwig Edinger and Charles’ brother, Clarence Luther Herrick, 1858–1904] were generally regarded as the founders of comparative neurology as an organized scientific discipline, the one in Germany the other in the United States.(Herrick 1955, p. 1)

Edinger’s research interests, however, had by no means been limited to neuroanatomy and pathology, since he was likewise engaged with issues of animal psychology and human psychoanalysis (Plänkers 1996, pp. 180–94). With respect to the scope of his collaborations, Edinger was quite innovative for his time, combining neuroanatomy with psychology, as can also be seen from the related cases of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) at the University of Vienna, Auguste Forel (1848–1939) at the University of Zurich, and Oscar Vogt at the Neurological Central Station in Berlin (Stahnisch 2008, p. 79f.).

Edinger further had a high esteem for clinical issues, which often served as a vantage point for his laboratory studies. For example, when he gave Goldstein a clinical research position in the neuropathological department of his institute, he had been faced with the situation that soon after the outbreak of the First World War, the latter was offered the directorship of two Frankfurt military hospitals (so-called Reservelazarette) (Kreft 1997, p. 134). It is quite significant to see that Edinger, who clearly thought that Goldstein would be his research associate, gave him full support for the decision to exclusively work in the hospital with brain-damaged soldiers—by saying: “Your work with patients is of a much higher importance than my theoretical work in the laboratory” (Edinger qtd. after: Goldstein 1971, p. 5).

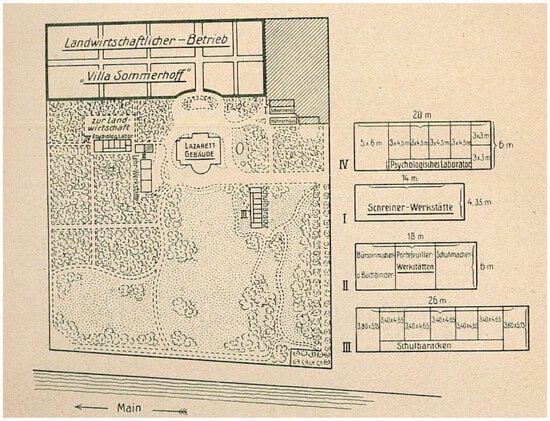

Yet Edinger and Goldstein continued collaborating, even when the latter had assumed the directorship of the so-called Institute for Research into the Consequences of Brain Injuries (Institut zur Erforschung der Folgeerscheinungen von Hirnverletzungen) in the Villa Sommerhoff in Frankfurt (Benzenhöfer and Kreft 1997, p. 35; Kreft 2005, pp. 24–6). Their scientific collaboration is reflected in a number of Edinger’s publications on regenerative processes in the brain and spinal cord during wartimes (e.g., Edinger 1917). In his institute, Goldstein worked not only on the development of better neurological diagnoses, but also on early rehabilitation of patients with brain damage that led to quite some success—leading back 73 percent of its patients into their pre-war jobs (Goldstein and Gelb 1918, pp. 18–23). Goldstein’s Villa Sommerhoff already had (see Figure 4) what Edinger kept in mind for the future direction of his institute: a ward for medical and orthopedic treatment, a psychophysiological laboratory for patient diagnosis, a training school and, further, working places for the hospitalized patients (Goldstein 1919b):

Figure 4.

Map drawing of the Neurological Institute (Clinical Department—Villa Sommerhoff) in Frankfurt am Main with adjacent functional buildings housing the rehabilitation units, 1919, from Goldstein K, Die Behandlung, Fürsorge und Begutachtung der Hirnverletzten: zugleich ein Beitrag zur Verwendung psychologischer Methoden in der Klinik. Leipzig: F. C. W. Vogel, 1919b, Figure s. n., p. 3. The image is in the Public Domain.

Hence, the institutional set-up, as well as its interrelation with the other neurological institutions in Frankfurt, was especially designed to serve the needs for a “transfer of knowledge” (Weinberg 1967, pp. 159–71; Knorr-Cetina 1999, pp. 2–11) from research animals and comparative anatomical methods to the understanding of the human brain. This endeavor was also supported by a model of division of labor between the neuropathological, the clinical–neurological, and the psychological investigations going on in what was not a large institute.

Regarding the conceptual side of its neuroscientific research, we may see that brain functions—or what Edinger often called the “correlative identity of form and function”—served as a heuristic hypothesis, which could change between questions asked on the morphological side and those that were brought about by physiological definitions (Edinger 1908, p. 1), or, as was pointed out by Glees:

Edinger has been one of the first to see the general biological problems of the brain. One can also say that Edinger was one of the first to realize the importance of interrelating structure and function.(Glees 1952, p. 253)

Although this was definitely not a new scientific concept, as the approach may be traced back—on purely functional grounds—to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it nevertheless served as a regulative “proto” idea for Edinger when organizing his institute (Fleck 1983, pp. 60–65). The interrelationship of form and function is especially reflected in Edinger’s so-called “Aufbrauchtheorie” of nervous diseases—of what he thought to be a using-up of central nervous tissue (Edinger 1908). As had recently been pointed out by philosopher of science Marcus Jacobson, similar to other degeneration theories at the time, Edinger assumed an incongruence between the genetic set-up of the nervous system and its external demands (Jacobson 1993, p. 259–67). If such external demands could not be coped with through other nervous tissues, then neuritis—after strenuous work or other noxious influences like cold temperatures, syphilis, or sleeplessness—gradually led to the degeneration of brain structures (Harrington 1996, pp. 143–47). Edinger’s Aufbrauchtheorie thus served as a model for combining clinical and psychological approaches with neuroanatomical or neuropathological ones, and it was also applied to the study of consciousness:

We will reach a point where the assumption of consciousness will be necessary, but doubtless this point is pushed further away even if the question is gradually answered in more appropriate forms. When we will be able to explain certain actions without the basic assumption of consciousness, then the time has come that scientists could explain the unknown or the mythical of today. This approach is to be a bottom-down approach and may follow the same lines after which traditional research insights [on the matter have] climbed up to the knowledge of consciousness.(Edinger 1913, p. 1f; author’s transl.)

Using a modern neurophilosophical term, Edinger’s position could be understood as that of an eliminative materialist, in which the term “consciousness” might one day be reduced to a material substrate without precise criteria as to what would actually count as such a reduction and if it could ever be achieved (Schoenfeld 2006, p. 76). Put in Edinger’s words of 1917, “the mythical phenomena in science can only be solved when the methods are available” to do this (Edinger 1917, p. 1; author’s transl.).

Although we may find this prominent reductive view in Edinger, there is also a complementary position in his work, which presupposed that for the practical neurologist and psychiatrist, human consciousness is an ever unexplainable and self-evident phenomenon, without which:

We [will] have no clue how it comes about that the activity of a single part of the nervous system can be rendered conscious to the individual human person. The endeavor to fill the remaining gap between the mind–body dualism must be seen as doomed to failure.(Edinger [1919] 2005, p. 75; author’s transl.)

This view is also reflected in his own research together with Goldstein on the consequences of circumscribed brain lesions, an approach that he had sometimes called jocularly the “anatomical generals’ ordonnance map” (“anatomische Generalstabskarte”) of the brain (Edinger qtd. after Emisch 1991, p. 79f). This future map of the brain represented anatomical findings that could later be used as vantage points for neurophysiological and neuropsychological research—in a bottom-down fashion—with Edinger’s firm conviction that neuroanatomical data had not become obsolete. Having seen these remarkable and sometimes even complementary perspectives in Edinger, the cognitive basis of the Neurological Institute could probably be best summarized in what Goldstein used to call a plurality of assumptions (~“Pluralität der Auffassungen”), an interdisciplinary parallelism of assumptions and approaches in Edinger’s work (Goldstein 1919a, p. 1).

6. Discussion

By looking closer at the social and cultural context and the organizational set-up of Edinger’s Neurological Institute in Frankfurt am Main, it has become possible in this article to describe the contours of the integrative whole of interdisciplinary methods in Edinger’s research program. This attempt at linking a comparative form of neurology to the human psychological faculties has certainly had its origin in previous influences from Edinger’s teachers, such as Carl Gegenbaur’s “genetic method” as well as Friedrich Leopold Goltz’s (1834–1902) ablation studies on dogs. They were once and again an inspiration for him to draw comparisons from the animal to the human brain, as described at the Twelfth Congress for Internal Medicine on 12–15 April 1893 (Edinger 1893). These views were integrated into a synthetic view that Edinger had taken over from Adolf Kussmaul (1877), relying on cell-cell-interactions in the brain that were to mediate between psychological and physiological brain functions and hence allowed for sustaining the humane in mind–brain interactions (Finger 2000, pp. 259–63).

Although Ludwig Edinger and his institute have often been perceived in research literature in terms of functional neuroanatomy and traditional lines of microscopical research,10 looking at these diverse perspectives shows that his career and notion of neuroscientific progress stand at the edge of an older institutionalized research style (Harwood 1993), which became developed into a multi-perspective and advanced scientific conception of his Neurological Institute in Frankfurt.

Now, in connecting the conceptual developments, experimental findings, and research set-up of the Neurological Institute, a couple of insights may be drawn from this case for a modern picture on interdisciplinarity in the neurosciences. Firstly, despite the fact that there was an essentially practical dimension to interdisciplinary research, the historically interesting feature lies in Edinger’s central break with an old style of hierarchical institutional research arrangements at many university institutes at the beginning of the twentieth century (Stahnisch 2009). In institutional terms, this development was paralleled by the Neurobiological Institute in Berlin of Oscar and Cécile Vogt or the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Psychiatrie in Munich (Ritter and Roelcke 2005). The decisive events took place in the two decades between 1910 and 1930, and it is quite remarkable that these institutions preserved some autonomous status, which may be one of the factors for their scientific success.

Secondly, how did Edinger’s research conception relate to the set-up of the institute? It is interesting to see that Edinger’s personal convictions, his influence, and his optimism strongly helped to set up the Neurological Institute at a time and in an anti-Semitic local situation not really in favor for his academic plans. On the one hand—and from a biographical perspective—we may see the founding of the institute as Edinger’s only way out to carry on with his academic interests, what could have easily led into failure and the personal withdrawal into his private practice in Frankfurt. On the other hand—from an institutional perspective—the local context of pre-university learned societies stands out as an important enabling factor for Edinger’s work. The preexisting scientific culture of the city, which had not had a university until 10 June 1914, and the founding of (neuro-) science in a mercantile surrounding were crucial, as Edinger’s Institute benefitted strongly from wealthy Jewish Frankfurt citizens, who acted as research donors and were especially interested in new scientific and clinical answers to brain damage.

Thirdly, from the position of institutional history, it is often arduous to draw the line between a physical institution and its scientific actions and products. The example of Edinger’s Neurological Institute points further than viewing medical research institutions solely from a perspective intra mures. When applying the concept of interdisciplinarity here, one realizes that in Edinger’s case, it was a broad research network, one which combined his Neurological Institute physically with his private neurological practice. The Senckenberg Institution, a neurological outpatient clinic, and Goldstein’s Institute for Research into the Consequences of Brain Injury were all part and parcel of Edinger’s research network in Frankfurt. Yet although one gets the impression of it being quite dispersed over the city—as the Faculty’s Edinger Commission stated in 1919 when trying to restructure the institute after Edinger’s death—informal communication structures and discussion circles helped to integrate the research localities into a functional and comprehensive whole. This level of arrangement has long been neglected in historical scholarship, although it was imperative for the success of Edinger’s institute and one of the necessary features that drove interdisciplinary research in the neurosciences at the beginning of the twentieth century. This was clearly nurtured through many national and international guest researchers who took Edinger’s concepts and ideas back to their home institutions and gradually worked on transforming these as well, such as the Berlin neurologist Fritz Heinrich Lewy (1885–1950), who—in 1914—worked together with Edinger for four months, and later created his own successful research laboratory in Berlin, before he was forced to emigrate to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA. Similarly, the experimental neuroanatomist Paul Glees, who was working together with Cornelius Ubbo Ariëns Kappers (Scholz 1961, pp. 37–40), the director of the comparative-anatomical department at the University of Amsterdam in the 1930s (Eling and Hofman 2014), later became an influential neuroglia researcher and medical teacher both at the University of Oxford in England and the University of Göttingen in Germany.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study does not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The ahistorical notions of “neuroscience” and “neuroscientists” are here understood as precursors to the new interdisciplinary field, which incorporated many autonomous contemporary brain research approaches such as neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, neuropathology, clinical neurology, and biological psychiatry, etc. However, the modern notion of “neuroscience” was only introduced in 1962 through the planning of the “Neurosciences Research Program” by Boston biophysicist Francis O. Schmitt (1903–1995). See, for example, Schmitt (1990, pp. 214–17). |

| 2 | The German notion of “Nervenärzte” is rather untranslatable into English notions. It encompasses both physicians trained in “neurology” and “psychiatry” as clinical practitioners, who likewise addressed “mental and nervous diseases” in their work. For the implications and scope of the German notion of Nervenärzte, see Breidbach (1997, pp. 15–22). |

| 3 | Here I will make use of the interpretation given by Gerald Geison in his foregoing work. See, for example, Geison (1981, p. 26). |

| 4 | On the development and context of this portrait painting, see also: Mann (1974, pp. 325–28). |

| 5 | Edinger (1876, p. 685; author’s translation). This is a remarkable observation, given the focus on the cerebral cortex in neuroanatomy throughout the nineteenth century. Cf. Finger (2000, pp. 137–76). |

| 6 | Johann Christian Senckenberg (1707–1772) was a medical doctor and natural scientist, who founded several non-university research institutes, collections, and a municipal hospital in Frankfurt am Main during the eighteenth century. His philanthropic estate fell completely to Frankfurt’s magistrate, after he had tragically died by falling off a scaffolding at the new pediatric hospital that he had recently endowed. The pediatric hospital was close to completion, before Senckenberg’s early and unfortunate death. The Senckenberg Society of Natural Scientists, named in his honor, is still in place today (Bauer 2006, p. 67). |

| 7 | Also, Edinger’s emphasis that he had modeled his own university institute on the organizational sketch of the Obersteiner Institute in Vienna gave rise to continuous debates among the later members of the Edinger Commission, who sought to find an adequate successor after he had died in 1918 so that the interdisciplinary legacy of the Frankfurt institute could be further developed following the First World War. See the collection on the “Edinger Commission” in the University Archives in Frankfurt am Main, as a partial collection in the Frankfurt Institute for the History and Ethics of Medicine (Edinger Commission 1919, p. 8); author’s translation. |

| 8 | This form of organization also included the Villa Sommerhoff, as well as an associate unit of paleoneurology at the Senckenberg-Museum led by Tilly Edinger (1897–1967) (Kohring and Kreft 2003, p. 432). She left Germany in 1939, due to Nazi persecution, and became a pioneer in the field of paleoneurology at Harvard University. See, for example, Buchholtz and Seyfarth (1999, pp. 351–61). |

| 9 | Edinger could show that it would lead to the thalamus rather than the cerebellum, as Meynert had originally thought. See, for example, Meynert (1872, pp. 694–808) and Emisch (1991, p. 69). |

| 10 | See, for example, the biographical notes and obituaries of Adolf Wallenberg (1915), Paul Glees (1952), as well as Wilhelm Krücke and Hugo Spatz (1959). |

References

- Adelman, Gerald. 2010. The Neurosciences Research Program at MIT and the Beginning of the Modern Field of Neuroscience. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 19: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angermann, Matthias C., and Holger Steinberg, eds. 2005. 200 Jahre Psychiatrie an der Universität Leipzig: Personen und Konzepte. Berlin: DeGruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, Toby A. 1988. Organizing Biology: The American Society of Naturalists and Its Affiliated Societies,’ 1883–1923. In The American Development of Biology. Edited by Ronald Raininger, Keith R. Benson and Jane Maienschein. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, pp. 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, Geneviève. 2010. From Photography to Cinematography: Recording Movement and Gait in a Neurological Context. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 11: 255–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Thomas. 2006. Johann Christian Senckenberg und seine Stiftung. Forschung Frankfurt 4: 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bechmann, Zara. 1999. Heinrich Obersteiner. Leben und Werk. Diss. med. Tübingen: University of Tübingen. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel, William. 2001. Cognitive Neuroscience. Relating Neural Mechanisms and Cognition. In Theory and Method in the Neurosciences. Edited by Peter K. Machamer, Rick Grush and Peter McLaughlin. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 81–111. [Google Scholar]

- Benzenhöfer, Udo, and Gerald Kreft. 1997. Bemerkungen zur Frankfurter Zeit (1917–1933) des jüdischen Neurologen und Psychiaters Walther Riese. Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Nervenheilkunde 3: 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Borck, Cornelius. 2005. Hirnströme. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Elektroenzephalographie. Göttingen: Wallstein. [Google Scholar]

- Breidbach, Olaf. 1997. Die Materialisierung des Ichs: Zur Geschichte der Hirnforschung im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholtz, Emily A., and Ernst-August Seyfarth. 1999. The Gospel of the Fossil Brain: Tilly Edinger and the Science of Paleoneurology. Brain Research Bulletin 48: 351–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, William. 1985. The Cognitive Basis of the Discipline: Claude Bernard on Physiology. Isis 76: 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, H. Michel. 1974. The TEA Set: Tacit Knowledge and Scientific Networks. Social Sciences 4: 165–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierig, Sierig. 2000. Urbanization, Place of Experiment and How the Electric Fish Was Caught by Emil DuBois-Reymond. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 9: 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierig, Sven, Jens Lachmund, and Jane Andrew Mendelsohn. 2003. Introduction: Toward an Urban History of Science. Osiris 18: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1876. Über die Schleimhaut des Fischdarmes nebst Bemerkungen zur Phylogenese der Drüsen des Dünndarms. Straßburg: Inaugural-dissertation vorgelegt der medicinischen Facultät zu Straßburg im Elsaß. Vorgelegt von Ludwig Edinger aus Worms. Bonn: Verlag von Cohen & Sohn. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1881. Untersuchungen zur Physiologie und Pathologie des Magens. Habilitationsschrift, Gießen: University of Gießen. Leipzig: Hirschfeld. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1885. Zehn Vorlesungen über den Bau der Nervösen Zentralorgane. Leipzig: Vogel. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1886. Bericht über die Leistungen auf dem Gebiete der Anatomie des Nervensystems über das Jahr 1885. Schmidts Jahrbücher der Gesamten Medizin 212: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1893. Über die Bedeutung der Hirnrinde im Anschluss an den Bericht über die Untersuchung eines Hundes, dem Goltz das ganze Vorderhirn Entfernt hatte. Wiesbaden: F. Bergmann. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1896. Untersuchungen über die vergleichende Anatomie des Gehirns III. Neue Studien über das Vorderhirn der Reptilien. Abhandlungen der Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 19: 89–119. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1904. Carl Weigert—Nekrolog. Jahresberichte des Ärztlichen Vereins zu Frankfurt a. M. 48: 34–58. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1908. Der Anteil der Funktion an der Entstehung von Nervenkrankheiten. Wiesbaden: F. Bergmann. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1913. Über Rassenhygiene. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 1917. Ludwig Bruns. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Nervenheilkunde 56: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, Ludwig. 2005. Mein Lebensgang. Erinnerungen eines Frankfurter Arztes und Hirnforschers. Edited by Gerald Kreft, Werner Friedrich Kümmel, Wolfgang Schlote and Reiner Wiehl. Frankfurt am Main: Waldemar Kramer. First published 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger Commission. 1919. Collection on the “Edinger Commission”. Frankfurt am Main: University Archives of the Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main. [Google Scholar]

- Eling, Paul. 2018. Neuroanniversary 2018. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 27: 186–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, Paul, and Michel A. Hofman. 2014. The Central Institute for Brain Research in Amsterdam and its Directors. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 23: 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emisch, Heidemarie. 1991. Ludwig Edinger—Hirnanatomie und Psychologie. Stuttgart and New York: Fischer. [Google Scholar]

- Emisch, Heidemarie. 1992. Ludwig Edinger 1855–1918. In 175 Jahre Senckenbergische Naturforschende Gesellschaft. Edited by Wolfgang Klausewitz. Frankfurt am Main: Kramer, pp. 311–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eulner, Heinrich H. 1970. Psychiatrie und Neurologie. In Die Entwicklung der medizinischen Spezialfächer an den Universitäten des deutschen Sprachgebietes. Edited by Heinrich H. Eulner. Stuttgart: Enke, pp. 257–82. [Google Scholar]

- Finger, Stanley. 2000. Minds Behind the Brain. A History of the Pioneers and their Discoveries. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, Ludwik. 1983. Über die wissenschaftliche Beobachtung und die Wahrnehmung im Allgemeinen. In Erfahrung und Tatsache. Gesammelte Aufsätze. Edited by Ludwig Schäfer and Thomas Schnelle. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- Geison, Gerald. 1981. Scientific Change, Emerging Specialties, and Research Schools. History of Science 19: 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glees, Paul. 1952. Ludwig Edinger 1855–1918. Journal of Neurophysiology 15: 251–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glees, Paul. 1964. Ludwig Edinger. In Geschichte der Mikroskopie. Leben und Werk großer Forscher. Edited by Hugo Freund H and Alexander Berg. Frankfurt am Main: Umschau Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Kurt. 1919a. Ludwig Edinger (Nachruf). Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 44: 114–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, Kurt. 1919b. Die Behandlung, Fürsorge und Begutachtung der Hirnverletzten: Zugleich ein Beitrag zur Verwendung psychologischer Methoden in der Klinik. Leipzig: F. C. W. Vogel. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Kurt. 1971. Notes on the Development of my Concepts. In Selected Papers/Ausgewählte Schriften. Edited by Aaron Gurwitsch and Elizabeth M. Goldstein-Haudek. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Kurt, and Adhémar Gelb. 1918. Psychologische Analysen hirnpathologischer Fälle auf Grund von Untersuchungen Hirnverletzter. I. Abhandlung. Zur Psychologie des optischen Wahrnehmungs- und Erkennungsvorgangs. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 41: 1–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerstein, Notkar. 2000. Die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft in der Zeit der Weimarer Republik und im dritten Reich; Wissenschaftspolitik in Republik und Diktatur. Munich: C. H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerstein, Notkar. 2012. Die Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main. Von der Stiftungsuniversität zur staatlichen Hochschule. Göttingen: Wallstein, vols. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, Anne. 1996. Reenchanted Science, Holism in German Culture from Wilhelm II. to Hitler. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, Jonathan. 1993. Styles of Scientific Thought. The German Genetics Community, 1900–1933. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herrick, Charles Judson. 1955. Clarence Luther Herrick: Pioneer Naturalist, Teacher, and Psychobiologist. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 45: 1–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, Renate, and Wolf Siegbert, eds. 1997. Die Juden der Frankfurter Universität. Frankfurt am Main and New York: Campus Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, Marcus. 1993. Foundations of Neuroscience. Berlin and New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Karenberg, Axel. 2006. Neurosciences and the Third Reich. Journal for the History of the Neurosciences 15: 168–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr-Cetina, Karin. 1985. Das naturwissenschaftliche Labor als Ort der “Verdichtung von Gesellschaft”. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 17: 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr-Cetina, Karin. 1999. Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, Peter J. 2013. Charcot, La Salpêtrière, and Hysteria as Represented in European Literature. Progress in Brain Research 206: 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kötter, Rudolf, and Pierre Balsiger. 1999. Interdisciplinarity and Transdisciplinarity: A Constant Challenge to the Sciences. Issues in Integrative Studies 17: 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kohring, Rolf, and Gerald Kreft. 2003. Tilly Edinger: Leben und Werk einer jüdischen Wissenschaftlerin. Stuttgart: E. Schweizerbart‘sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Kreft, Gerald. 1997. Zwischen Goldstein und Kleist—Zum Verhältnis von Neurologie und Psychiatrie im Frankfurt am Main der 1920er Jahre. Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Nervenheilkunde 3: 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kreft, Gerald. 2005. Deutsch-jüdische Geschichte und Hirnforschung – Ludwig Edingers Neurologisches Institut in Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt am Main: Mabuse-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter, Alma. 1996. Deutschsprachige Neurologen und Psychiater—Ein biographisch-bibliographisches Lexikon von den Vorläufern bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Mit einem Geleitwort von Hanns Hippius und Paul Hoff. Munich, New Providence, London and Paris: DeGruyer, vols. 1, pp. 275–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberg, Georg W. 1987. Gerd Peters: 8.5.1906–14.3.1987 (Nachruf auf Peters). Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berichte und Mitteilungen 87: 82–5. [Google Scholar]

- Krücke, Wolfgang. 1963. Ludwig Edinger (1855–1918). In Große Nervenärzte. Edited by Kurt Kolle. Stuttgart: Thieme, vol. 3, pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Krücke, Wolfgang, and Hugo Spatz. 1959. Aus den Erinnerungen von Ludwig Edinger. In Ludwig-Edinger-Gedenkschrift wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft. Wiesbaden: Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kümmel, Werner F. 1993. Säulen der Wohltätigkeit: Jüdische Stiftungen und Stifter in Frankfurt am Main. Medizinhistorisches Journal 28: 275–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kussmaul, Adolf. 1877. Die Störungen der Sprache: Versuch einer Pathologie der Sprache. Leipzig: F.C.W. Vogel. [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir, Timothy. 1993. The Disciplines of Nature and the Nature of Disciplines. In Knowledges: Historical and Critical Studies in Interdisciplinarity. Edited by Ellen R. Messer-Davidow, David R. Shumway and David J. Sylvan. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, pp. 70–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir, Timothy. 1997. Instituting Science: The Cultural Production of Scientific Disciplines. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewey, Frederic Henry. 1970. Ludwig Edinger (1855–1918). In The Founders of Neurology, 2nd ed. Edited by Webb Haymaker and Francis Schiller. Springield: C. S. Thomas, pp. 111–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Gunther G. 1972. Senckenbergs Stiftung und die Frankfurter Republik der Ärzte im 19. Jahrhundert. Medizinhistorisches Journal 7: 244–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mann, Gunther G. 1974. Das Porträt des Neuroanatomen Ludwig Edinger von Clovis Corinth (1909). Medizinhistorisches Journal 9: 325–8. [Google Scholar]

- Meynert, Theodor. 1872. Vom Gehirn der Säugetiere. In Handbuch der Lehre von den Geweben des Menschen und der Thiere. Edited by Salomon Stricker. Leipzig: Engelmann, pp. 694–808. [Google Scholar]

- Neumärker, Klaus-Jürgen, and Andreas J. Bartsch. 2003. Karl Kleist (1879–1960)—A Pioneer of Neuropsychiatry. History of Psychiatry 14: 411–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, Serge, and Ludovic Ferrand. 1999. Wundt’s Laboratory at Leipzig in 1891. History of Psychology 2: 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, Paul E. 2015. Ludwig Edinger: The Vertebrate Series and Comparative Neuroanatomy. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 24: 26–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiffer, Jürgen. 1998. Zur Neurologie im “Dritten Reich” und ihren Nachwirkungen. Nervenarzt 69: 728–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinch, Trevor. 2009. Cold Fusion and the Sociology of Scientific Knowledge. Technical Communication Quarterly 3: 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plänkers, Thomas. 1996. Psychoanalyse in Frankfurt am Main. Zerstörte Anfänge. Wiederannäherung. Entwicklungen. Edited by Michael Laier and Heinrich H. Otto. Tübingen: Psychosozial-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Prithishkhumar, Ivan J. 2012. Ludwig Edinger (1855–1918): Founder of Modern Neuroanatomy. Clinical Anatomy 25: 155–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg. 1997. Toward a History of Epistemic Things. Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riese, Walther, and Kurt Goldstein. 1950. The Brain of Ludwig Edinger. An Inquiry into the Cerebral Morphology of Mental Ability and Left-Handedness. Journal of Comparative Neurology 92: 133–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Hans-Jörg, and Volker Roelcke. 2005. Psychiatric Genetics in Munich and Basel between 1925 and 1945: Programs-Practices-Cooperative Arrangements. In Politics and Science in Wartime: Comparative International Perspectives on the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Edited by Carola Sachse and Michael Walker. Chicago: Chicago University Press, pp. 263–88. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Ralf. 1996. Stadt und Bürgertum in Frankfurt am Main. Ein besonderer Weg von der städtischen zur modernen Bürgergesellschaft 1760–1915. München: Oldenbourg. [Google Scholar]

- Schlote, Wolfgang. 2002. Ludwig Edinger (1855–1918)—Neurologe, Frankfurter Arzt und Weltbürger. In Die Frankfurter Gelehrtenrepublik. Edited by Gerd Böhme. Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner, pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Francis O. 1990. The Never-Ceasing Search. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, Robert L. 2006. Explorers of the Nervous System: With Electronics, An Institutional Base, A Network of Scientists. Boca Raton: Universal Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, Willibald, ed. 1961. 50 Jahre Neuropathologie in Deutschland 1885–1935. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Siefert, Helmut. 2001. “Den Kranken dem Leben zurückgeben.” Zur Geschichte der Psychiatrie in Frankfurt am Main. In In waldig ländlicher Umgebung. Das Waldkrankenhaus Köppern: Von der agrikolen Kolonie der Stadt Frankfurt zum Zentrum für soziale Psychiatrie Hochtaunus. Edited by Christina Vanja and Helmut Siefert. Kassel: Euregioverlag, pp. 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Marianne L. 1968. Kurt Goldstein 1878–1965. In The Reach of Mind. Essays in the Memory of Kurt Goldstein. Edited by Marianne L. Simmel. New York: Springer, pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2003. Making the Brain Plastic: Early Neuroanatomical Staining Techniques and the Pursuit of Structural Plasticity, 1910–1970. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 12: 413–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2008. Psychiatrie und Hirnforschung: Zu den interstitiellen Übergängen des städtischen Wissenschaftsraums im Labor der Berliner Metropole—Oskar und Cécile Vogt, Korbinian Brodmann, Kurt Goldstein. In Psychiater und Zeitgeist. Zur Geschichte der Psychiatrie in Berlin. Edited by Hanfried Helmchen. Berlin: Pabst, pp. 76–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2009. Transforming the Lab: Technological and Societal Concerns in the Pursuit of De- and Regeneration in the German Morphological Neurosciences, 1910–1930. Medicine Studies. An International Journal for History, Philosophy, and Ethics of Medicine & Allied Sciences 1: 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2010a. “Der Rosenthal’sche Versuch” oder: Über den Ort produktiver Forschung—Zur Exkursion des physiologischen Experimentallabors von Isidor Rosenthal (1836–1915) von der Stadt aufs Land. Sudhoffs Archiv 94: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2010b. German-Speaking Émigré-Neuroscientists in North America after 1933: Critical Reflections on Emigration-Induced Scientific Change. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften (Vienna) 21: 36–68. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2012. The Emergence of Nervennahrung: Nerves, Mind and Metabolism in the Long Eighteenth Century. Studies in History and Philosophy of the Biological and Biomedical Sciences 43: 405–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2016a. Die Neurowissenschaften in Straßburg zwischen 1872 und 1945. Sudhoffs Archiv 100: 227–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2016b. From ‘Nerve Fibre Regeneration‘ to ‘Functional Changes’ in the Human Brain – On the Paradigm-Shifting Work of the Experimental Physiologist Albrecht Bethe (1872–1954) in Frankfurt am Main. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 10: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahnisch, Frank W. 2020. A New Field in Mind. A History of Interdisciplinarity in the Early Brain Sciences. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnisch, Frank W., and Thomas Hoffmann. 2010. Kurt Goldstein and the Neurology of Movement during the Interwar Years—Physiological Experimentation, Clinical Psychology and Early Rehabilitation. In Was Bewegt uns? Menschen im Spannungsfeld zwischen Mobilität und Beschleunigung. Edited by Christian Hoffstadt, Franz Peschke and Andreas Schulz-Buchta. Bochum: Projekt Verlag, pp. 283–312. [Google Scholar]

- Strösser, Wolfgang. 1993. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neuropathologie und Neuroanatomie e. V. 1950–1992. Eine Untersuchung zur Entwicklung der Gesellschaft und zur Förderung des Faches Neuropathologie in Deutschland. Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neuropathologie und Neuroanatomie e. V. [Google Scholar]

- Toodayan, Nadeem. 2016. A Convenient “Inconvenience”: The Eponymus Legacy of Sir William Richard Gowers (1845–1915). Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 26: 50–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, Heinrich. 1905. Über die Anatomie, das Wesen und die Entstehung mikrocephaler Missbildungen, nebst Beiträgen über die Entwickelungsstörungen der Architektonik des Zentralnervensystems. Wiesbaden: F. Bergmann. [Google Scholar]

- Von Recklinghausen, Friedrich Daniel. 1882. Über die multiplen Fibrome der Haut und ihre Beziehung zu den multiplen Neuromen. Festschrift zur Feier des fünfundzwanzigjährigen Bestehens des pathologischen Instituts zu Berlin. Herrn Rudolf Virchow. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wallenberg, Adolf. 1915. Ludwig Edinger zum 60. Geburtstage. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 55: 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, Alvin M. 1967. Reflections on Big Science. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, Frederic G., Francis O. Schmitt, Judith P. Swazey, and Gerald Adelman. 1975. The Neurosciences: Paths of Discovery. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).