Abstract

The following article explores ideas of early ecological thinking within the natural sciences of early-19th-century Germany and discusses its possible roots. It tries to shed some light on the work of Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus who developed a holistic understanding of nature. The historical background and 18th-century ideas Treviranus relies on will be described—namely, the ‘great chain of being’, the idea of nature as a vast network of interconnected living beings and the question about the existence of vital forces that cause movement, growth or reproduction. Reference will especially be made to Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus’ main work, the six-volume Biologie oder Philosophie der lebenden Natur für Naturforscher und Aerzte (Biology or Philosophy of Living Nature for Natural Scientists and Physicians) published in Göttingen between 1802 and 1822 and the somewhat later synopsis Erscheinungen und Gesetze des organischen Lebens (Phenomena and Laws of Organic Life) printed in Bremen in 1831 and 1832.

1. Introduction: Today’s Reception of Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus

“When we see how the living nature is arranged, or when we are regarding the relations in which we find the living nature […] we find one single huge organism.”1 As early as 1802, Reinhold Gottfried Treviranus, in his work Biologie oder Philosophie der lebenden Natur für Naturforscher und Aerzte (Treviranus 1802, 1803, 1805, 1814, 1818, 1822)—which was supplemented later on by Erscheinungen und Gesetze des organischen Lebens (Treviranus 1831, 1832) expresses an image of nature that recalls modern ecology and today’s ways of looking at nature. No doubt, the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change and endangered ecological balances have increasingly forced us to realise humanity’s dependence on and embeddedness in nature. Nevertheless, over a long time, ideas about nature as a giant organism, as cited above, seemed to be of Romantic origin—being rather speculative than representing a reality.

Introductions to the history of biology today list Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus parallel to Michael Christoph Hanow (1695–1773), Jean Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) or Karl Friedrich Burdach (1776–1847) and he is mainly remembered as one of those who coined the term ‘biology’. Treviranus was involved in the innovations that took place in botany and zoology at the time—especially developing comparative anatomy, physiology and embryology (Junker 2004; Höxtermann and Hilger 2007).2 But apart from that, he is usually named among those that were close to Romantic natural philosophy. His work appeared to be rather unscientific and highly speculative, being part of a Romantic ‘interlude’ in the emerging modern natural sciences. It was interpreted as a Romantic view of nature, part of a countermovement to the Enlightenment, turning to dreamlike fantasies, resulting from a disappointment after the French Revolution (Jahn et al. 1982, p. 311).3 The failed faith in reason seemed to have opened the door to irrationality. As late as 2007, Torsten Kanz confirmed this kind of reception: “Such an understanding of ‘biology’ or ‘life theory’ meant turning away from mechanistic approaches […]. Treviranus was accused of encouraging vitalist thinking, for example of replacing rational explanations with metaphysical constructs of vital forces inherent in all organisms and thus at the same time negating the applicability of the laws of chemistry and physics to living bodies” (Kanz 2007, pp. 100–21).

Nevertheless, Treviranus seems to have been well informed about what was going on during his time; his connections to the chemically researching natural scientists are striking, as Brigitte Hoppe has shown (Hoppe 1983). Andrea Gambarotto, on the other hand, has analysed how Treviranus was in fact influenced by intellectuals of the time, for example that he took over some of Immanuel Kant’s and also Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling’s assumptions concerning interactions between organism and environment—and at the same time transforming them (Gambarotto 2018, p. 91ff). Gambarotto even describes him as a pioneer of evolution theory (Gambarotto 2014).4 Elke Witt, in turn, stated in 2007 that Treviranus’ work shows many changes in conceptions: “that he moved from a materialistic-mechanistic approach of explaining living nature, to a vitalist interpretation and to an almost spiritualistic view of the living in the last books” (Witt 2007, pp. 178–79). She even argues that his work could be read in terms of a pluralism of theories, as an attempt to establish a natural science that no longer insists on one uniform system but approaches the complex phenomenon of ‘life’ from different perspectives.

No doubt, the aspects in Treviranus’ work are complex, and it is impossible to take all of them into account here. The following will rather focus on the broader historical context of his work—on questions of continuity and change. To what extent did this ‘modern’ biology of Treviranus take up ‘pre-modern’ ideas of nature? To what extent did it establish innovative ideas at the time? Can it really be considered as ‘speculative’ or even ‘unscientific’? Did naturalists, when turning away from mechanistic ideas in the late 18th and early 19th century, really abandon rational patterns of explanation, as has been argued? Is empirical natural research replaced by ‘metaphysical constructs’ or even a ‘theory pluralism’ in Treviranus’ work? Was Romantic natural science really an anti-Enlightenment movement that left the new, empirical, scientific knowledge aside? Was it a speculative natural philosophical theory that was ultimately unscientific by today’s standards?

2. Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus and the Historical Background

“Indeed, what naturalist could deserve it more to be called a philosopher of nature, a seer and a mystagogue of natures’ secrets, than Treviranus? […] The scientific researchers of all Europe will feel devastated by the message of his death. For Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus was a man whose extensive, profound knowledge outweighed that of an entire faculty, whose achievements alone outweighed those of an entire academy.” (Weber 1837, p. 4)5 These words, probably spoken at Treviranus’ funeral and written down by Wilhelm Ernst Weber in 1837, show clearly that Treviranus was widely known during his lifetime. But from a modern point of view, this statement is rather irritating: the priesthood of the ‘mystagogue’ and the status as a scientific luminary are probably rather mutually exclusive. Was he a grandiose scientist or a ‘mystagogue’—a priest, a mystic?

Reinhold Gottfried Treviranus’ ancestors supposedly came from Trier—hence presumably the name ‘Treviranus’.6 Among his own contemporaries, his younger brother, Ludolph Christian Treviranus, a botanist, was in fact much better known than Reinhold Gottfried. As late as 1894, the ADB (Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie) devoted an article four times as long to Ludolph Christian Treviranus. Nevertheless, today Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus, as mentioned above, is regarded as one of the co-founders of modern ‘biology’ and the younger brother is no longer remembered.

Born in 1776 as the eldest son of eleven children, Reinhold Gottfried Treviranus grew up in Bremen, where he was educated at a grammar school. According to Maria Hermes, he studied mathematics and medicine in Göttingen in 1793 (Hermes 2011).7 There, he attended lectures by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and received his doctorate in 1796. Returning to Bremen, he worked as a teacher of mathematics and medicine at the local grammar school and at the same time practised as a doctor at the Bremen city hospital. In 1797, he married his former patient, Elisabeth Focke. Because of his frequent illness (he caught tuberculosis in 1794), he rarely left the Hanseatic city and his family. But in addition to his teaching and medical activities, he was scientifically engaged in what he called ‘biology’. He died in Bremen in 1837 during an influenza epidemic.

What was Treviranus’ concern? And how did this lead to the emergence of ‘biology’? In the preface to his Biologie (Treviranus 1802), he explains his ‘research project’; he writes “There have always been men, and Linné himself was one of them, who realised that all those artificial systems, without relation to higher purposes, were only mere rubbish. They did not reach to the highest goal, and therefore everything they produced remained mere piecemeal. The ultimate goal of any natural research, however, is the investigation of the driving forces by which that large organism which we call nature is kept in eternal activity […]. We have only a mere register, not yet a science of nature, as long as we cling eternally to these systems, and do not proceed to the attainment of that goal”.8 Treviranus thus explicitly turns away from what had been early modern science, from collecting and classifying. He is interested in the study of what he called ‘life processes’, what he and his contemporaries subsumed under the term ‘physiology’—the inner ‘driving forces’ of an ‘organised’ nature, the vital processes of living beings. Thus, the central concept for Treviranus is ‘life’: “Our intention is a new attempt […]. The objects of our research will be the various forms and phenomena of life […]. This science that deals with these objects will be called biology or life science.”9 For him, ‘life’ is everywhere where you find growth, movement or reproduction—phenomena that cannot be explained by external forces. He states “We call an animal or a plant alive as long as we still find signs of growth and movement i.e., activity, in them. But at the same time, we think of this activity as something in the body to which we ascribe life, produced from within, not from without”.10 The vital force interacts with what is outside, but it is an independent force (Cheung 2014, p. 73ff). Inner forces and external forces are clearly distinguished: “The sea, which is moved by the storm, is also in activity. Yet we do not ascribe life to it: Why? Because that motion is initiated by external forces. Every movement, then, which is caused by external forces, which are transmitted, we call a mechanical one, and those movements by which life expresses itself differ from the mechanical ones. They are not brought about by external but by internal causes.”11 Mechanistic patterns of explanation—of movement for example—are in fact not rejected here (also in the realm of the so-called ‘organised nature’, the living beings), but they are clearly determined as being brought in from outside. Thus, external forces have an effect on living beings, but the expressions of life as such arise from an inner force that cannot be explained mechanistically. Treviranus admits that, at a first glance, the inner forces are often difficult to distinguish from external forces. But for him, this is nothing other than the result of the integration of living beings into their environment: “If the living body was a completely isolated being, and every reason for its movements only in itself, then the boundary between this and the mechanical movements would be easy to draw. But all expressions of its activity are products of an interaction between itself and the external world […].”12

Treviranus now sees himself as somebody who is exclusively concerned with these ‘inner life forces’ of animate nature—a ‘physiologist’ and not a ‘physicist’. He is dealing with life processes, with the inner functions of living beings. One has to bear in mind though that around 1800, the three-kingdom doctrine (dividing nature into animals, plants and minerals) had already given way to a two-kingdom doctrine. Many naturalists now distinguished ‘organised bodies’ from ‘unorganised bodies’: humans, animals and plants now differed from minerals because of their vital properties. This distinction also determines Treviranus’ thinking: “We find visible nature divided into two great kingdoms, the lifeless and the living”,13 he states in the introduction to his Biologie. Treviranus explicitly turns to the latter, the group of ‘living’, ‘organised’ bodies—to the realms of ‘biology’.

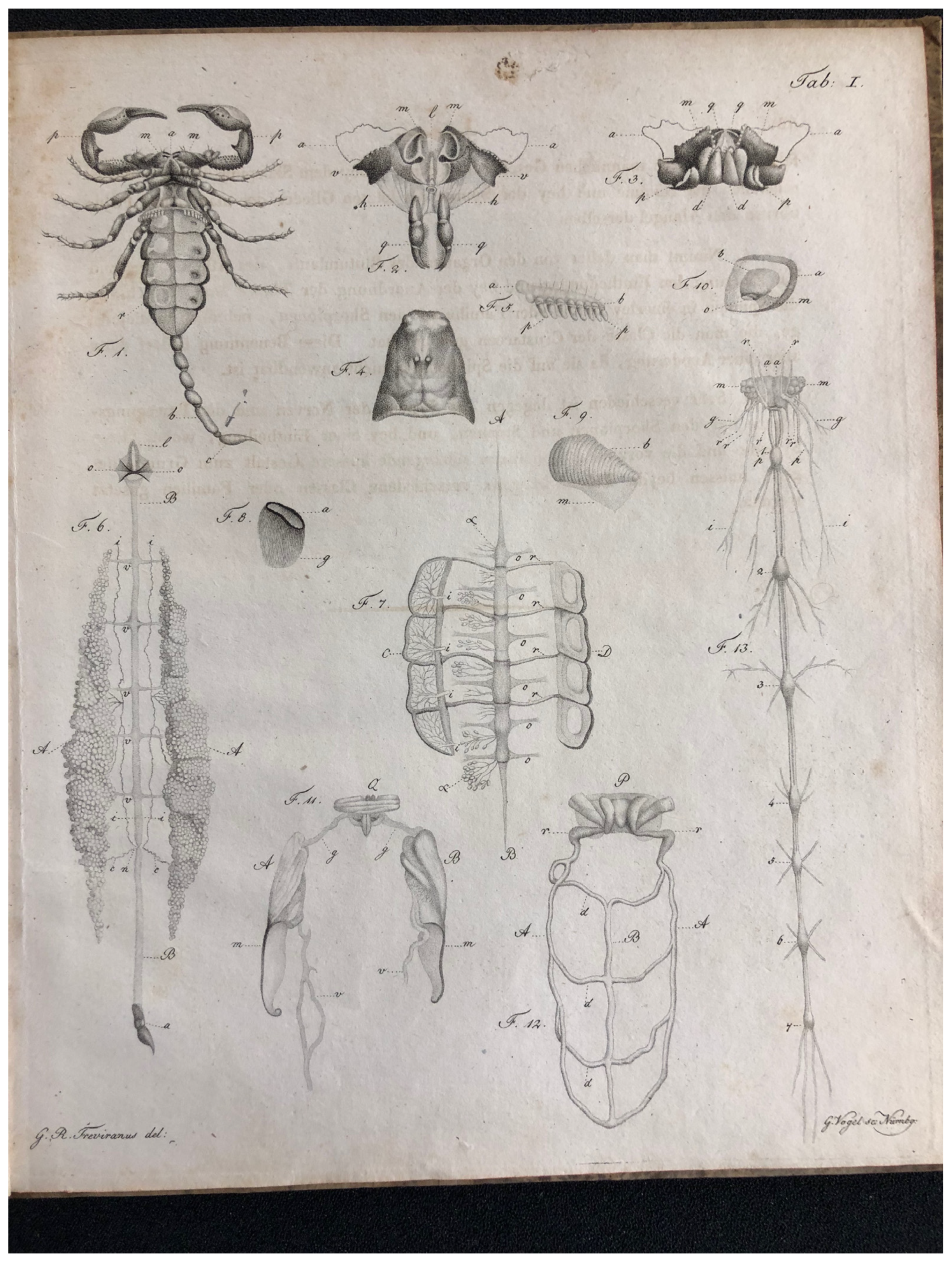

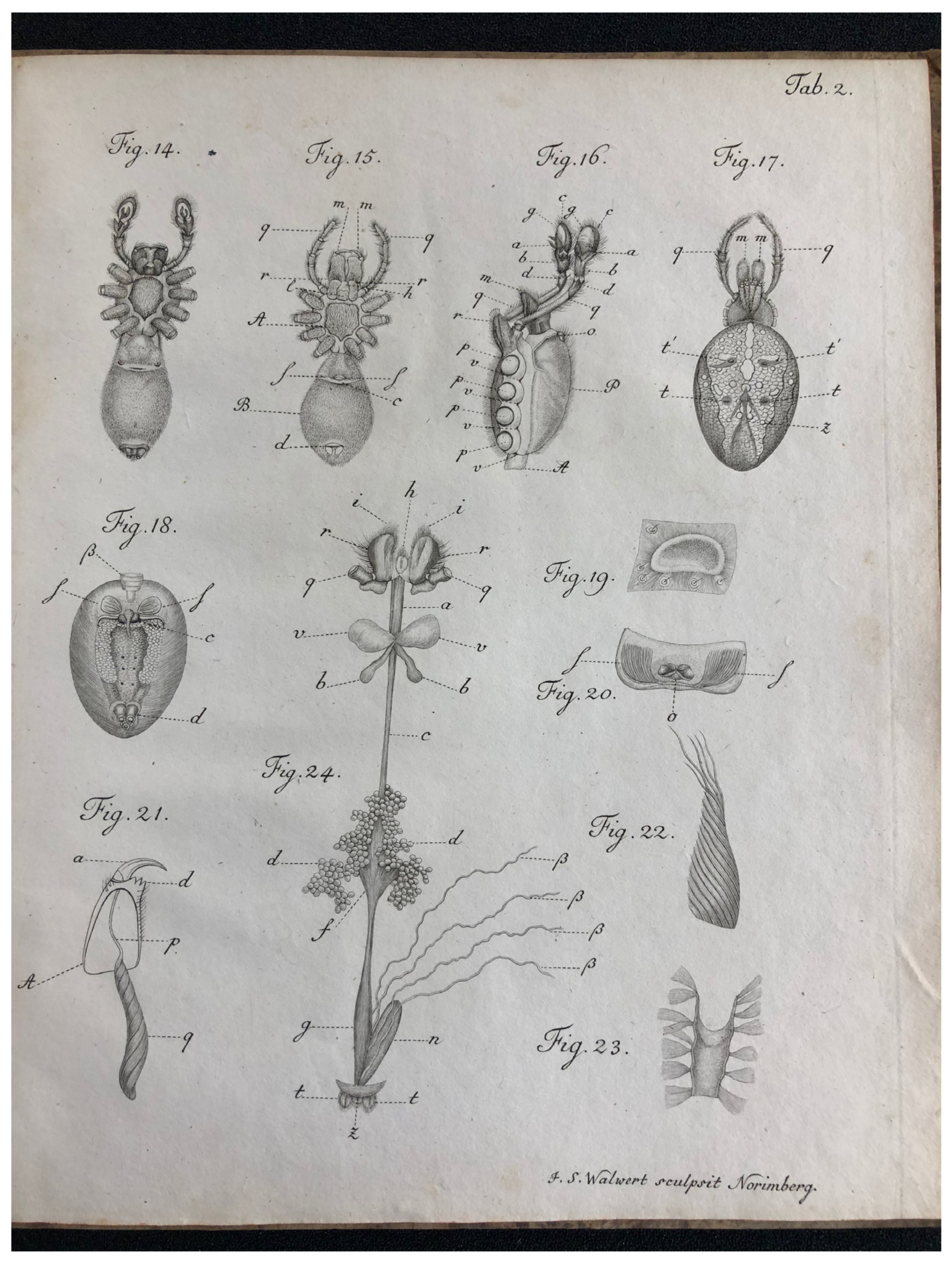

Once we look at the figures Treviranus himself drew on the internal structure of spiders, this becomes illustrated (see Figure 1: Arachnids). Of course, even at the beginning of the 19th century, there were still zoologists who aimed to collect, record and classify arachnids (such as Carl Wilhelm Hahn for example, Hahn 1820–1836), and the recording of the European spider species was far from complete. But this is not what Treviranus is interested in. He focuses on the internal and external organs of the arachnids, from the digestive tract to the spiders’ eyes. Consequently, he also entitled his work on spiders Ueber den innern Bau der Arachniden (On the Internal Structure of Arachnids, Treviranus 1812). He describes the anatomy of the animal and the internal operations of the organs that maintain the spider’s life processes, and he finds similar characteristics in all living organisms: instincts, passions, arbitrary actions, reproduction, sexual difference, waking and sleeping, youth and old age, health and disease. Even if they differ in one way or another, all of these organisms share these phenomena. Moreover, they all interact with each other.

Figure 1.

Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold, Ueber den innern Bau der Arachniden, Nürnberg, verlegt bei Johann Leonhard Schrag, 1812, Tafeln 1 und 2; Universitätsbibliothek Basel, Signatur: Zool Cv 2:1:1.

Treviranus in no way discredits the findings of the preceding period, but he wants to go further than his predecessors. In his work, he refers to a myriad of natural scientists—botanists, zoologists and anatomists. He mentions Marcello Malpighi, Georges Cuvier and Georges-Louis Lerclerc de Buffon, and he recalls names that we today usually assign to the so-called ‘physico-theologians’, to those who connected their description of nature with the praise of an ingenious creator who was believed to direct nature’s harmony and perfection, such as Nehemiah Grew, Robert Boyle, Pierre Lyonnet, Jan Swammerdam or Charles Bonnet. Treviranus did of course not distinguish between those who wrote explicitly physico-theological works and those whose works only showed a physico-theological framing or completely omitted it. In other words, Treviranus was working at a time when physics (the knowledge of nature) and metaphysics (theological-philosophical concepts) were not yet completely separated. He of course knew that naturalists of the 18th century had linked natural science and their belief in God, their belief in a divinely caused nature. But for him, this did not discredit their observations, their concepts or their work. If so, what traces of these ‘pre-modern’ ideas can be found in Treviranus, who is said to have founded something ‘new’, a new science called ‘biology’?

To anticipate one finding: The ‘argument from design’ (which is so central to physical theology), the explanation of the complex order of nature from a divine providence and through an all-embracing divine intention,14 is not present in his work. And describing natural phenomena and natural objects is no longer intended to prove the wisdom of God and God’s rationality, Gods’ intelligent arrangement of nature. The term ‘God’ does not appear at all in Treviranus’ text. Nevertheless, he recurs to physico-theological ideas that had been discussed at length in the 18th century.

3. Preceding Concepts? The Aristotelian Scala Naturae and the Great Chain of Being

How did Treviranus explain the order of nature? In his Biologie, Treviranus refers to an eighteenth-century concept of the natural order that was very popular: the idea of the so-called ‘great chain of being’. The ‘great chain of being’, based on ancient Greek philosophy, can in fact be found in many works of those who dealt with zoological or botanical subjects in late 18th and early 19th century. Arthur Lovejoy, in his work The Great Chain of Being, described this concept as early as 1936 (Lovejoy [1936] 1965). Lovejoy even considered it to be the most powerful idea about nature in the 18th century.

Of course, the originally Aristotelian idea of a scala naturae had long since merged with Christian ideas. It had been linked to the belief in a divine and ingenious creator who had created the abundance of species at the beginning of all time. But one central feature of this concept remained important even at the turn of the 19th century: nature was arranged in gradual gradation; species had been located on a continuum, on a finely graded scale, to allow perfect abundance and plenitude (Feuerstein-Herz 2007). Lovejoy described this natural order as a “chain […] of an infinite number of links, reaching from the lowest things, just escaping non-being, in hierarchical succession through all stages to the ens perfectissimum. […] Each of these members differed from the one immediately above and below it by the smallest possible degree of difference” (Lovejoy [1936] 1965, p. 59).

In the medieval (Christian) form, this chain had ranged from the angels down to the smallest living beings of the invisible world or even down to the minerals and elements. But in the second half of the 18th century, with the expanding natural sciences, the idea of the ‘chain’ became even more concrete. It is well known how Charles Bonnet (to whom Treviranus refers in some places) in his Traité d’Insectologie of 1745 filled the idea of the chain of being with concrete elements and designed complex gradations of species (Bonnet 1745). For Bonnet too, species differed only minimally from each other. In his Betrachtungen über die Natur (Contemplations of Nature), published in German in 1774, he states “Nature descends by imperceptible steps from man to the polyp, from the latter to the sensitive plant, from the latter to the truffle. Higher species are at all times related by some character to the lower, and these to the still lower”.15 Bonnet himself wanted to find these species and their minimal differences, clinging to the principle of continuity. In doing so, he also insisted on a preformist view of the world, on the pre-existence of germs since the days of the creation.

But the idea of a ‘chain of being’ was not restricted to Bonnet’s conception of nature. In the physico-theological treatises, it is omnipresent. The innumerability, the interdependencies of humans, animals and vegetation seemed to prove the infinite wisdom of God. The natural scientist and theologian Heinrich Sander (1754–1782) is a key example of this physico-theological spelling out of the connections and chains in nature. His book Von Gottes Güte und Weisheit in der Natur (Of God’s Goodness and Wisdom in Nature)16 was published in Basel in 1778 and was reprinted in at least seven more editions until 1827. In late 18th century, it was a ‘bestseller’ that dealt almost exclusively with the links and the mutual dependencies of man, animal and plant. It was especially the ingenious interplay, the arrangement of creatures and the interdependence of all creatures that was seen as irrefutable evidence for the wisdom and benevolence of God: interdependencies that formed one huge harmony where every item and every living being had its place, well suited to serve the preservation of the greater whole (or the ecological system, as we would put it today). In Enlightenment natural theology, God thus became the reasonable, benevolent and wise creator, the ultima ratio, the supreme rational being. Sander states “Creation is a single whole. Everything is laid out according to a plan, everything has symmetry, proportion, measure, number and weight, there is nothing that should not fit into the general design of God. […] God rules the world by means of these thousandfold concatenations and connections”(Sander 1784).17 The ultimate purpose is the harmony of the whole: “The greatest gift of beauty is unity, and this is in nature. Millions of creatures interweave their activities. A single great purpose, the bliss of the whole, is produced. In nature there is no contradiction anywhere, there cannot be. […] The whole earth proves that a supreme, omnipotent, wise and benevolent being holds life in its hands. The more one comes to know nature, the more one realises the interrelation of all creatures, the more the idea that God is Father and Benefactor of the world gains ground.”18

Sander’s ideas remained present well into the 19th century. As late as 1804, one of his students claims “Nature walks along with majestically slow steps, rises from level to level, and, inexhaustible in variety, sets up myriads of beings, which, like the rungs of a ladder, always stand one above the other in a higher order. The stone borders on the plant, the plant on the animal, the animal on man, man on the spiritual world. But what a distance from the pebble to the fir, from the fir to the oyster, from the oyster to the Hottentot, from the Hottentot to the wisest man! Nevertheless, nature is the most perfect whole. There is nowhere a gap; it links being to being, and connects them unnoticed, connects them so finely, blurs their boundary lines so gently, that the explorer believes he is still walking in the same realm of nature, when he has already moved far away in the next. Nature, it is true, knows no division into classes. Each individual being is a ring of natures’ immeasurable chain, just as there are not two things in the world that are perfectly alike: only the limited human mind, tired of the immense series of created beings, has marked out certain points of rest.”19

Similar works can be found easily. In Julius Bernhard von Rohr’s Phyto-Theologia, for example, these chains within nature are described in detail—here in particular in relation to vegetation, to the ‘plant world’ (Von Rohr 1745). It is the same idea that is predominant: the wonderful order, the overall harmony, is maintained as one cog meshes with the other. This ‘ingenious arrangement’ was described in all variations, up to detailed descriptions of entire ecosystems (if one wants to use this modern terminology here).

Even natural scientists who did not argue in an exhaustive physico-theological way, such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, Treviranus’ teacher, Polycarp Erxleben or Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin (See for example: Blumenbach 1779; Erxleben 1777; Jacquin 1800, p. 14), all referred to the idea of a continuous transition from one species to another. They contrasted what they called a ‘natural system’ to the ‘artificial system’ that would draw sharp boundaries. The latter was seen as a simplifying model—useful in daily life or for teaching but not depicting reality. The idea of living organisms located on a quasi-continuum, of organisms that were hardly distinguishable from one another, could of course not be easily represented in manuals or textbooks; in practice, the Linnaean classification was still used for classification purposes.

This ‘chain of being’ and the principle of continuity remained plausible for zoological and botanical researchers for another reason as well: within the chain of being and the continuity thesis, the diversity of species was to be explained. Species that were seemingly located between animals and plants, such as the so-called animal plants (‘Thierpflanzen’, such as polyps) or plant animals (‘Pflanzenthiere’, such as the mimosa that showed movement), seemed to present the links between the various kingdoms of nature. The border between plant and animal seemed to blur exactly at that point.

Towards the end of the 18th century, the image of the chain of being became more and more differentiated and, to a certain extent, also horizontalised. It was turned into an image of multiple chains and links. A veritable network of interwoven living beings emerged. Naturalists such as Johann Hermann from Strasbourg, for example, now designed complex net-like schemes of the so-called ‘natural systems’ of kinship among animals. These schemes became increasingly confusing (Diekmann 1992).20 (Sander, a few decades earlier, used the image of ‘wallpaper’ in which everything was interwoven.) (Sander 1784, p. 184).

Back to Treviranus: for Treviranus too, ‘gradation’ is no longer a simple sequence of steps; it consists of multiple chains in all directions. He even links it to the mixing of ‘substances’. In the first volume of Biologie, he explains these gradations in a whole chapter and argues that there is still a lot to be discovered.21 According to him, living nature can be divided into two areas that merge into one another: “The whole of living nature can be divided into two large divisions: in the one, nitrogen predominates, in the other, carbon. The former comprehends the animals and animal plants, the latter the plant animals and plants. The former approach the animal, the latter the vegetable organisation.”22

These ‘two divisions’ then, again, are finely graded: “For each of these two divisions there is a maximum and a minimum […]. The maximum of the animal organisation we find in mammals, and especially in man, the minimum in infusion animals. The maximum of plant-like formation is peculiar to the dictyledons with a many-leaved corolla (flowering plants, note by the author), the minimum to several sexes of the families of sponges, conferves, seaweeds and lichens. There is an uninterrupted gradation from each maximum of living nature to each of its simplest forms.”23 Continuity is thus present in Treviranus’ model; although, here, complex sequences of stages or steps also exist side by side. The ‘chain’ is also arranged according to mutual effects, purposes and interdependencies, like a net.

At the end of this chapter, Treviranus—like many others—refers to Leibniz and states “Nature, Leibnitz said, forms a whole. Its parts are so closely connected with each other, that it is impossible for the senses and even the imagination to indicate the point where one ends and the other begins. This statement remains true and certain! But if this wise man called the whole a single chain, this comparison must not be repeated. Not one, but thousands and thousands of chains, interwoven with infinite art into the tightest knot, make up the whole of nature.”24 Even the boundary between the ‘living’ and the ‘lifeless’ might be dispersed one day: “But on whose side lies the truth, on ours, who have been accustomed to the distinction between a lifeless and a living nature since our youth […] or on the side of those who […] still find a faint reflection of life in those phenomena? Anyone who considers this question will hardly set himself up as an arbiter; he will admit that we are not yet able to establish a boundary between the living and the lifeless nature.”25

According to Treviranus too, humans represent the highest level of existence, which he believes to be able to prove anatomically on the basis of the complexity of the human brain: “Furthermore, this gradation is confirmed in the brain. Even in mammals, one misses many peculiarities of the human brain. […] In birds the convolutions of the brain disappear completely. […] The brain of amphibians and fish is even simpler.”26 (And this, he thinks, also applies for the complexity of other organs, especially the reproductive organs.).

Concerning gradation, even man can be located on different ‘levels’ and become similar to the animal. Treviranus reports on a case found on the Shetland Islands (referring to the Edinburgh Philosophical Journal of 1819) about “David Tate, born deaf and blind, a young man of five and twenty living at Fetlar, one of the Shetland Islands, who was on such a low level of human existence that he could not accept an upright position other than by force, and whose entire communication with the external world was mediated only by the sense of touch.”27

4. The Huge Organism and the Disappearance of God

The reader of the Treviran text, of his description of nature as one universal organism, is unquestionably reminded of other natural philosophers of the time, especially of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775–1824). No doubt, Treviranus knew Schelling, who published the Von der Weltseele, eine Hypothese der höhern Physik zur Erklärung des allgemeinen Organismus (the idea of a ‘world soul’) a few years earlier (Schelling 1798). Treviranus’ brother Ludolph had listened to lectures of Schelling. And there are definitely concordances, as well as differences, between the Treviran understanding of nature and Schelling’s idea of a ‘world soul’ (Gambarotto 2018, p. 96).28

For Treviranus, the whole world is to be understood as a single context, as one huge organism: “The whole universe is one single system without any boundaries […]. Each individual organism is dependent on the universe.”29 And all organisms interact with each other: “If the entire sensually comprehensible world is only one single organism, if the smallest thing in it is what it is only by the fact that it interacts with the largest thing, and if the largest thing has its existence only through the smallest thing, then it is pointless to want to determine something about even one atom without taking the universe into consideration.”30 Each individual organism must fulfil its purpose in the whole organism, because “the whole realm of living organisms constitutes a member of the great organism, and each living individual must contribute its share to the preservation of this”31.

Nevertheless, Treviranus rarely refers explicitly to Schelling in his six volumes of Biologie oder Philosophie der lebenden Natur and rather illustrates his ideas by depicting interdependencies in nature. One could maybe even argue the other way round: that many natural philosophers at the turn of the century (including Schelling) drew their ideas from preceding ideas about the order of nature. We have already seen that in physico-theological literature of the 18th century, conceptions of nature as one big ‘system’ were in fact en vogue. Although there, of course, the emphasis had been on God as the one who had created this ‘system’, this huge organism. God is not mentioned in Treviranus. But nevertheless, his ideas are reminiscent of the physico-theological explanations, because each individual organism has its place and has to fulfil its purpose for the bliss of the whole. In the physico-theologists work, in Sander’s book, in the edition of 1784, we read “No fold of the world may be different, no being may be missing, no force may transgress its order. […] The grass, every cornflower is precisely linked to the whole atmosphere, indeed to the whole solar system”.32 Here, already in the eighteenth century, in this total organism of nature, man becomes one organism among others; Sander writes “From the milky way in the sky down to the mosquitoes dancing around the pond, nothing is small, nothing is insignificant. For God nothing is small, nothing contemptible. […] We are so proud that we almost always think of ourselves as the centre of creation, as the sun around which everything should revolve. But what are we more than a unity in the directory of all God’s creatures? Is it not a ridiculous delusion to believe that God has made everything in heaven, in the ocean, and on earth merely for our sake? […] Poor man, who then are you in the state of God? A thousand and another thousand kinds of creatures populate this earth with thee. You fill no more than a single place; nature takes care of the preservation of the water beetle just as well as it takes care of you.”33 Thus, Sander turns away from an anthropocentric view of the world34 and confesses “The privileges of God, which the Creator has given you, are not so great that you alone may rule, and declare everything you cannot devour dead and barren.” (Sander 1784, p. 51). He even shows concrete examples that describe the disaster arising if man interferes with the natural systems. He tells, for example, a story from America, where forests had been destroyed and plants that had been important for the natural balance were lost: diseases appeared because the air had no longer been sufficiently purified by the plants (Ibid., p. 66ff). Sander connects this with the idea of the ‘bliss of the whole’: “The greatest law of beauty is unity, and this is in nature. Millions of creatures interweave their effects so that a single great purpose, the bliss of the whole, is maintained. There is nowhere in nature a contradiction, there cannot be. Everything that is and everything that happens relates to the whole, to the present and to the future. A magnificent spectacle for an archangel who understands more about it than we do!”35

Treviranus does not speak of a God-given harmony anymore, yet he observes—as Sander did before—the mutual linkages and the interdependencies in nature. And even Treviranus, in some places, speculates about a kind of final reason behind it. The great organism seems to be ‘rationally ordered’ when he writes in 1805, in the third volume of the Biologie: “Every living body exists through the universe, but the universe also exists mutually through it. A higher mind would be able to deduce from the given organisation of a single living individual the organisation of the rest of the world”.36

Whereas in late 18th century, physico-theological literature the whole of nature (including man) is seen as a total work of art, a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, originating from God’s genius, here, the reason behind the huge organism cannot be explained. In physico-theology, the investigation of the laws of nature, the scientific observation of nature had led to religious awe. In Treviranus’ work, on the other hand, the ecological interdependencies remain within nature; an external power directing the system does not appear. Creation is replaced by nature. But the relational structures and the mutual dependencies of living beings, the purposeful arrangements of nature within the framework of the laws of nature, remain. The question ‘What for?’, which the 18th century still provides with the answer ‘to the praise of God’, is omitted. The analysis remains within what can be described empirically. The archangel has vanished.

5. Souls, Life and the Vital Principle

In late 18th and early 19th century, many naturalists had already turned away from the Cartesian concepts—defining the animal as a soulless automaton body in contrast to the ensouled human being. The Cartesian dualism had obviously not answered the central question how body and soul interacted, what the ‘soul’ was and how it could be described, how it caused movement, etc. Thus, they searched for new models. (Whether the Cartesian concept of the animal had ever convinced those who researched botany or zoology is still subject to debate.)37

And Treviranus’ concern is no longer the explanation of the interaction of body and soul. The living being (man, animal and plant) is simply seen as one entity, driven by a ‘vital force’. The vital force behind every sign of liveliness is what he now calls ‘life’ itself. And ‘life’, he says, is a mystery, something we are not able to explain. The vital principle, the ‘life force’ (‘Lebenskraft’), maintains the organism of living beings, but there is no longer an opposition of body and soul. For the physico-theologians—and one could even say for naturalists of the 18th century—this primordial reason for ‘life’ had been unquestionably the divine. But Treviranus does not comment on this at all. He rather argues that all answers at this point are highly speculative. The divine act of creating life is thus replaced by an abstract ‘life force’, a vital principle that permeates all living things. It is causing growth, reproduction, movement, etc., but it cannot be explained any further. God is, as we have seen before, not mentioned. Consequently, Treviranus rarely uses the terminology of ‘the soul’; he speaks of the ‘life force’ of every living organism. In the sixth volume of Biology or Philosophy of Living Nature, he even devotes an entire chapter to this subject, under the title “Connection of Physical Life with the Intellectual World”, where he puts this up for discussion: “There is a double view of the connection of the physical with the intellectual. Either spiritual and material forces are quite unlike each other; to the body of the animate the spirit is bound as an alien being. Or the spiritual and the physical are not only with but also through each other.”38 Treviranus tends to stick to what he sees: the inseparable existence of mind and body. And his solution to this problem lies somehow in the middle, avoiding a final decision. While defining a ‘living matter’ or ‘self-activity’ within all living beings, he ultimately does not specify where these vital forces come from. Life remains a mystery. Already in the first volume, he admits: “But that basic force is to us what colour is to the blind-born, a philosophy which undertakes to solve this task a priori is therefore no longer philosophy, but fantasy.”39 He now uses the terminology of ‘self-activity’: “The origin of all life lies in a principle whose essence is self-activity.”40 And he devotes his detailed empirical investigations to these activities, to the life processes. And in researching this ‘life force’, he is concerned with modern scientific methods: observation, experiment and verifiability.

Like Bonnet and other predecessors, Treviranus resolutely connects these vital forces with the theory of gradation and he asks himself how far mental forces extend within the gradual sequences and steps of nature. His answer is unambiguous: due to the principle of continuity, mental powers also extend into the animal kingdom. He even distinguishes between different mental powers in animals, such as the capability to invent things or the ability to remember: “Memory and the ability to recollect are the most widespread mental powers in animal nature. Even the insects give clear and sometimes striking evidence of their possession of these powers, such as the bees, for example, when they return in spring to the places where they were fed in autumn.”41 On the basis of the gradation theory, these forces even extend into the plant kingdom, since here, too, not only reactions to external stimuli can take place but also movements, growth processes, etc. These life processes are a result of the inner strength, the inner vital force. The connecting ‘link’ between man and animal—on the continuous ladder of gradation—is the monkey. About the apes, he writes “Compare the ape with man: read the news of reliable observers of the mental abilities of the orang-outang: the distance between the ape and man will, however, be big. But the ape cannot be denied the possession of similar, though far more limited, mental powers than are given to man. The animal seems to seek and avoid, to desire and detest, to love and hate, like man. […] The animal also remembers the past, which would not be possible without the consciousness of existence, and acts, where instinct alone cannot guide it, with deliberation and choice of means, thus with freedom.”42

6. Conclusions

The example of Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus shows that scientists like him were no longer concerned with classifying, collecting and perfecting the stores of knowledge, something that had been the central scientific concern and scientific technique of the early modern period. Scientists of the early 19th century were now dealing with the questions of “modern” natural science—in Treviranus’ case, the functioning of organs in animals, such as in spiders. In doing so, he started from a premise that assumed active forces in nature, ‘life forces’. These are, he says, not further explicable. According to Treviranus, life forces are inherent in all living organisms—man, animal and plant. And all of these are organisms. Nature itself represents a giant organism, in which complex interdependencies and interconnections prevail. It is in fact still an open question how holistic ideas such as the Treviran image of nature might have paved the way for 20th-century theories (e.g., the Gaia hypothesis developed by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis).

Treviranus himself, in any case, recalls eighteenth-century thought: the multiplied and extended ‘chain of being’. Relying on these concepts of the ‘great chain of being’, gradation still determines the order among living beings for Treviranus. But the idea of nature as an overall system which is structured by finest gradation now raises questions about the distribution of mental forces within nature. Thus, animals and plants are maybe not seen as ‘ensouled’, but they have vital powers, mental powers. A Cartesian separation into an automaton world of animals and plants on the one side, facing a human soul given by God on the other side, is no longer a convincing explanation.

Moreover, God is no longer mentioned. The life force as a formative, creative and ultimately inexplicable principle replaces him. Only in very few places in Treviranus’ work can one conceive a transcendental power, characteristically rather recalling ancient terminology when he states “That we look for the reason of life, which was already honoured in the childhood of biology with the name of a spirit of life, or Archeus. It is true that our present age rejects this perception, calls it a hyperphysical hypothesis, and puts in its place the mere form and mixture of matter. But that fundamental force is a hyperphysical being.”43 In Erscheinungen und Gesetze des organischen Lebens, which he published a little later, it becomes even clearer: “If we now proceed to the consideration of our object itself, we must first answer the question: What actually is life? Whoever utters this word names something mysterious. The region of life borders on the supernatural world” (Treviranus 1831).44

In that respect, Treviranus is well aware of his predecessors. He explicitly states “All observation […] and all reflection on it leads finally to an original cause which can only be guessed at. Therefore, all those who investigated the phenomena of life with a pure heart were people of deep religious feeling. I recall only Swammerdam, Bonnet and Linné. Their piety, of course, wore the dress of their education and their era. But even if Swammerdam appears to have been a bit of a raving theologian when he spoke of his great zootomic discoveries […] even if Bonnet and many other naturalists of the last century praised their own wisdom for that of the Creator, they still sought, though on the wrong track, the higher light whose reflection they had glimpsed.”45 Treviranus finds another solution: nature is permeated with a vital force; nature is a giant organism, a living system. He distances himself from a mechanistic or purely dissecting view of nature and, at the same time, distances himself from speculation: “Whoever fails to recognise this light in nature only sees an eternal cycle of coming into being and passing away. Whoever, dreaming or writing poetry, seeking words that are supposed to correspond to the light, and thus tries to explain the phenomena of life, does not find the truth, but only his fantasies everywhere”.46

Can the Treviran ‘Romantic natural science’, which was bound to organicist thinking and yet, at the same time, insisted on empiricism, be understood as being part of a ‘counter-Enlightenment’, an unscientific ‘interlude’ in the development of modern natural sciences? Treviranus rather appears as a renewed case for Late Enlightenment vitalism, as Peter Hanns Reill has described it. Reill defined Late Enlightenment vitalism as a movement that remained in fact linked to the ideals of Enlightenment. According to him, these ideas can neither be equated with Schelling’s philosophy of nature nor with a Romantic counter-Enlightenment or even a mystification of nature and rapturous view of nature—it is an image of nature that has its own contours (Reill 2005). Treviranus’ concept of the natural order is in fact based on central concepts of the Enlightenment. On one of the most powerful terms of the Enlightenment, ‘reason’, he writes “No purposeful activity is conceivable without an analogue of reason. Purposefulness is the actual character of the activity of reason […] every expression of life must therefore be the effect of a principle similar to reason” (Treviranus 1831).47 For him, nature is ‘rationally’ arranged and decipherable with the help of the mind, with reason.

It is undoubted that this kind of ‘Romantic natural science’ attempted to counter the fragmenting sciences at the beginning of modernity. Scientists such as Treviranus definitely searched for a great synthesis, an overall view of the world (See: Barkhoff 2009, pp. 209–26, esp. p. 210). He aims at this when he retrospectively writes in 1831: “The subject of which I shall communicate the results of my research in this work is the history of the origin, activity and decay of living beings and the relationships in which they stand to each other and to the rest of nature, their individual parts to each other and to the whole.”48 In doing so, he devotes himself to a (for the time being, final) linking of natural science and philosophy, focusing on the concept of life and the origin of life: “One can acquire profound mineralogical, chemical and physical knowledge without reflecting on the great questions: What, from where and for what purpose are we ourselves? But one cannot even gain any certainty about the origin of the infusion animals without coming up against questions that are linked to those questions”.49 Thus, in Treviranus, both the scientist and the philosopher speak; one merges into the other. Because only in researching nature, in the mirror of the natural environment, does man find his place. He says “To know oneself is the first law for the wise. But no one knows himself, as little in spirit as in body, who does not compare himself with the beings related to him.”50 Reading Treviranus, we might get an idea about the complexity of how theology and natural science developed together and maybe also how they finally became alienated from each other.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 107). „Wir betrachten hierauf die Organisation der lebenden Natur, oder die Verhältnisse, worin die lebende Natur, als ein einziger grosser Organismus.“ (All translations in the following: S.R.). |

| 2 | For example: (Junker 2004, p. 8). On the discussions about the term ‘biology’, in combination with ‘life force’: (Höxtermann and Hilger 2007, p. 100ff). |

| 3 | For example, in a basic introduction to biology: (Jahn et al. 1982, p. 311). |

| 4 | “The first naturalist in the German-speaking world to sketch the outline of a theory concerned with the historical transformation of living forms”. (Gambarotto 2014, p. 137). |

| 5 | (Weber 1837, p. 4). “In der That welcher Physiologe mögte in höherem und würdigerem Sinne, als Treviranus, ein Philosoph der Natur, ja ein Seher und Mystagog ihrer Geheimnisse, genannt zu werden verdienen? Daß über diese Todesbotschaft die wissenschaftlichen Forscher von ganz Europa sich bestürzt fühlen werden. Denn Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus war ein Mann, dessen umfangreiches, tiefes Wissen das einer ganzen Facultät, dessen Leistungen die einer ganzen Academie allein aufwogen.”. |

| 6 | For biographical details see: (Pagel 1894, p. 588). |

| 7 | For detailed information on both brothers and their work, see: (Hermes 2011). |

| 8 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. v). “Zwar gab es immer schon Männer, und Linné selbst gehörte zu diesen, welche einsahen, dass alle jene künstlichen Systeme, ohne Beziehung auf höhere Zwecke, nur schwerer Tand seyen. Allein sie erhoben sich nicht zu dem höchsten dieser Zwecke, und darum blieb alles, was sie in Beziehung auf diesen lieferten, blosses Stückwerk. Das letzte Ziel aller Naturforschung aber ist die Erforschung der Triebfedern, wodurch jener grosse Organismus, den wir Natur nennen, in ewiger Thätigkeit erhalten wird […]. Wir haben erst ein blosses Register, noch keine Wissenschaft der Natur, so lange wir ewig an diesen Systemen kleben, und nicht auf die Erreichung jenes Ziels ausgehen.”. |

| 9 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 4). “Unsere Absicht ist, einen neuen Versuch zu wagen […]. Die Gegenstände unserer Nachforschungen werden die verschiedenen Formen und Erscheinungen des Lebens seyn […]. Die Wissenschaft, die sich mit diesen Gegenständen beschäftigt, werden wir mit dem Namen der Biologie oder Lebenslehre bezeichnen.”. |

| 10 | Ibid., p 16. “Wir nennen ein Thier, eine Pflanze lebend, so lange wir noch Spuhren von Wachsthum und Bewegung, also von Thätigkeit, bey ihnen antreffen. Allein zugleich denken wir uns diese Thätigkeit als etwas in dem Körper, dem wir Leben zuschreiben, von Innen, nicht von Aussen hervorgebrachtes.”. |

| 11 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, pp. 16, 17). “Das Meer, das vom Sturme bewegt wird, ist auch in Thätigkeit. Dennoch schreiben wir ihm kein Leben zu: Warum? Weil ihm jene Bewegung durch äussere Kräfte mitgeheilt ist. Jede Bewegung nun, welche von äussern Kräften herrührt, welche mitgetheilt ist, nennen wir eine mechanische, und diejenigen Bewegungen, wodurch sich das Leben äussert, unterscheiden sich von den mechanischen, folglich dadurch, dass sie nicht durch äussere, sondern durch innere Ursachen hervorgebracht werden.”. |

| 12 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 17). “Wäre der lebende Körper ein ganz isolirtes Wesen, das jeden Grund seiner Bewegungen nur in sich selbst enthielte, so wäre die Gränze zwischen diesem und den mechanischen Bewegungen freylich leicht zu ziehen. Aber alle Aeusserungen seiner Thätigkeit sind Produkte einer Wechselwirkung zwischen ihm und der Aussenwelt.”. |

| 13 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 3). “Wir finden die sichtbare Natur in zwey grosse Reiche geschieden, in die leblose und in die lebende.” |

| 14 | On Europe-wide physico-theology as a combination of natural science and theology, see: (Blair and Von Greyerz 2020). |

| 15 | (Bonnet 1774, p. 371). “Die Natur geht durch unmerkliche Abfälle vom Menschen zum Polypen, von diesem zur empfindlichen Pflanze, von dieser zum Trüffel herab. Die höhern Arten hängen jederzeit durch irgendeinen Charakter mit den niedrigern, und diese mit den noch niedrigern, zusammen.” |

| 16 | This is based on the edition of 1784: (Sander 1784). |

| 17 | (Sander 1784, pp. 25, 26). “Die Schöpfung ist ein einziges Ganzes. Alles ist nach einem Riß angelegt, alles hat Symmetrie, Proportion, Maas, Zahl, und Gewicht, es ist nichts da, das nicht in den allgemeinen Plan der Gottheit passen solte. […] Vermittelst dieser tausendfachen Verkettungen und Verknüpfungen regiert Gott die Welt.”. |

| 18 | (Sander 1784, pp. 69, 71). “Das gröste Gesez der Schönheit ist die Einheit, und diese ist in der Natur. Millionen Geschöpfe verflechten ihre Würckungen so untereinander, daß ein einziger grosser Zweck, die Glückseeligkeit des Ganzen, erhalten wird. In der Natur ist nirgends ein Widerspruch, kann nicht sein. […] Die ganze Erde beweist es, daß ein höchstes, allmächtiges, weises, und gütiges Wesen die lange Kette des menschlichen Lebens in Händen hat. Je mehr man die Natur kennen lernt, je mehr man den Zusammenhang aller Geschöpfe untereinander einsieht, desto mehr gewinnt der Gedanke, daß Gott Vater und Wohltäter der Welt sei.”. |

| 19 | (Anonymous 1804, p. 39f). “Die Natur geht mit majestätisch langsamen Schritten einher, hebt sich von Stufe zu Stufe, und stellt, unerschöpflich an Abwechslungen, Myriaden von Wesen auf, die, wie die Sprossen einer Leiter, immer in höherer Ordnung übereinander stehen. Der Stein gränzet an die Pflanze, die Pflanze an das Thier, das Thier an den Menschen, der Mensch an die Geisterwelt. Aber welcher Abstand vom Kiesel zur Tanne, von der Tanne zur Auster, von der Auster zum Hottentotten, vom Hottentotten zum weisesten Menschen! Gleichwohl ist die Natur das vollkommenste Ganze; sie arbeitet in einem fort; thut nichts durch einen Sprung; lässt nirgends eine Lücke; knüpft Wesen an Wesen, und verbindet sie unvermerkt, schattiert sie so fein, verwischt ihre Gränzlinien so sanft, dass der Forscher noch in dem nemlichen Naturreiche zu wandlen glaubt, wenn er in dem darauffolgenden schon weit fortgerückt ist. Die Natur zwar kennt keine Klasseneintheilung; jedes einzelne Wesen ist ein Ring ihrer unermessliche Kette, so wie es in der Welt nicht zwey Dinge giebt, die einander vollkommen gleich wären: nur der eingeschränkte Menschenverstand hat sich, aus Ermüdung über die unübersehbare Reihe erschaffener Wesen, gewisse Ruhepunkte ausgesteckt.”. |

| 20 | These schemes became more and more confusing, Annette Diekmann has written on this: (Diekmann 1992). |

| 21 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, pp. 446–75). Section Six: “Gradationen der lebenden Natur”. |

| 22 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 447). “Die ganze lebende Natur lässt sich in Ansehung der Mischung ihrer Organisation unter zwey grosse Abtheilungen bringen: in der einen hat der Stickstoff, in der anderen der Kohlenstoff das Übergewicht. Jene begreift die Thiere und Thierpflanzen, diese die Pflanzenthiere und Pflanzen. Die erstern nähern sich insgesammt der animalischen, die letztern der vegetabilischen Organisation.” |

| 23 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 447). “Es giebt für jede dieser beyden Abtheilungen ein Maximum und ein Minimum in der gesammten Organisation […] Das Maximum der thierischen Organisation finden wir bey den Säugethieren, und vorzüglich bey dem Menschen, das Minimum bey den Infusionsthieren. Das Maximum der pflanzenartigen Bildung ist den Dictyledonen mit einer vielblättrigen Blumenkrone (Blütenpflanzen A.d.V.), das Minimum mehrern Geschlechtern aus den Familien der Schwämme, Conferven, Tange und Flechten eigen. Es gibt eine ununterbrochene Gradation von jedem Maximum der lebenden Natur zu jeder ihrer einfachsten Gestalten.” |

| 24 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, pp. 474, 475). “Die Natur, sagte Leibnitz, bildet ein Ganzes, dessen Theile in so enger Verbindung stehen, dass es den Sinnen und selbst der Einbildungskraft unmöglich ist, den Punkt anzugeben, wo der eine aufhört und der andere anfängt. Dieser Ausspruch bleibt wahr und gewiss! Aber wenn eben dieser Weltweise jenes Ganze eine e i n f a c h e Kette nannte, so darf diese Vergleichung nicht wiederholt werden. Nicht eine einzige, sondern Tausende und noch viele Tausende von Ketten, die mit unendlicher Kunst zu dem engsten Knoten verschlungen sind, machen das Ganze der Natur aus.” |

| 25 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, pp. 156, 157). “Auf wessen Seite liegt aber nun die Wahrheit, auf der unserigen, die wir, an die Unterscheidung einer leblosen und lebenden Natur von Jugend auf gewöhnt […] oder auf Seiten dessen, der […] in jenen Phänomenen noch einen schwachen Widerschein des Lebens findet? Wer unbefangen diese Frage erwägt, wird sich schwerlich zum Schiedsrichter aufwerfen, er wird eingestehen, dass wir noch nicht im Stande sind, eine Gränze zwischen der lebenden und leblosen Natur festzusetzen.”. |

| 26 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 453f). “Ferner bestätigt sich diese Gradation bey dem Gehirne. Schon bey den Säugethieren vermisst man viele Eigenthümlichkeiten des menschlichen Gehirns. […] Bey den Vögeln verschwinden die Windungen des Gehirns gänzlich. […] Noch einfacher ist das Gehirn der Amphibien und Fische.” |

| 27 | (Treviranus 1822, vol. 1, p. 16). “über den taub und blind gebornen David Tate, einen fünf und zwanzigjährigen, zu Fetlar, einer der Shetländischen Inseln, lebenden jungen Menschen, der auf einer so niedrigen Stufe des menschlichen Daseyns stand, dass er selbst die aufrechte Stellung nicht anders als gezwungen annahm, und dessen ganze Gemeinschaft mit der äussern Welt nur durch den Tastsinn vermittelt wurde.” |

| 28 | Andrea Gambarotto refers both to Treviranus’ critique of a Schellingian ‘world soul’ and to the adoption of an organizistic conception of nature. (Gambarotto 2018, p. 96). |

| 29 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, pp. 36, 37). “Dass das ganze Weltall nur ein einziges gränzenloses System ausmacht […] Jeder einzelne Organismus ist abhängig vom Universum”. |

| 30 | (Treviranus 1803, vol. 2, p. 3). “Ist die ganze Sinnenwelt nur ein einziger Organismus, ist das Kleinste in ihr das, was es ist, nur dadurch, dass es mit dem grössten in Wechselwirkung steht, und hat das Grösste sein Daseyn nur durch das Kleinste, so ist es ein eitles Beginnen, auch nur über ein Atom etwas bestimmen zu wollen, ohne auf das Universum Rücksicht zu nehmen.”. |

| 31 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 68). “…dass das ganze Reich der lebenden Organismen ein Glied des allgemeinen Organismus ausmacht, und dass jedes lebende Individuum zur Erhaltung dieses Gliedes das Seinige beitragen muss.”. |

| 32 | (Sander 1784, p. 71). “Keine Falte der Welt darf anders sein, kein Wesen darf fehlen, keine Kraft darf ihre Ordnung überschreiten. […] Das Gras, jede Kornbluhme steht mit der ganzen Atmosphäre, ja mit dem ganzen Sonnensysteme in genauer Verknüpfung.”. |

| 33 | (Ibid., p. 50f). “Von der Milchstrasse am Himmel herab bis zu den Mücken; die um den Teich tanzen, ist nichts klein, nichts geringfügig. Für die Gottheit ist nichts gering, nichts verächtlich. […] Wir sind so stolz, daß wir uns beinahe immer, als den Mittelpunkt der Schöpfung, als die Sonne, um die sich alles herumdrehen soll, ansehen. Aber was sind wir mehr, als eine Einheit im Verzeichnis aller Geschöpfe Gottes? Ist es nicht ein lächerlicher Wahn zu glauben, daß Gott alles im Himmel, im Ocean, und auf der Erde bloß um unsertwillen gemacht habe? […] Armer Mensch, wer bist Du dann im Staat Gottes? Tausend und wieder tausend Arten von Geschöpfen bevölkern diesen Wohnplatz mit Dir. Du füllst nicht mehr, als eine einzige Stelle aus, die Natur sorgt für die Erhaltung des Wasserkäfers eben so gut, als für dich.”. |

| 34 | Keith Thomas calls it “the dethronement of man”: (Thomas 1984, p. 165ff). |

| 35 | (Ibid., p. 69). “Das gröste Gesetz der Schönheit ist die Einheit, und diese ist in der Natur. Millionen Geschöpfe verflechten ihre Würkungen untereinander, daß ein einziger grosser Zweck, die Glückseeligkeit des Ganzen, erhalten wird. In der Natur ist nirgends ein Widerspruch, kan nicht sein. Alles, was ist, und alles, was geschieht, bezieht sich aufs Ganze, aufs Gegenwärtige, und aufs Zukünftige. Prächtiges Schauspiel für einen Erzengel, der davon mehr versteht als wir!”. |

| 36 | (Treviranus 1805, vol. 3, p. 552f). „Jeder lebende Körper besteht durch das Universum, aber das Universum besteht auch gegenseitig durch ihn. Ein höherer Verstand würde aus der gegebenen Organisation eines einzigen lebenden Individuums die Organisation der ganzen übrigen Welt abzuleiten im Stande sein.”. |

| 37 | Already as early as the 17th century, the English botanist John Ray contradicted the idea of the automaton body of animals. (Ray 1744, p. 55). Interestingly, even before the middle of the 18th century, Ray adds here that one could assume a kind of ‘plastick principle’, a kind of forming force (“but if it be material and consequently the whole Animal but a mere Machine, or Automaton, as I can hardly admit, then we must have recourse to a Plastick Nature”). |

| 38 | (Treviranus 1822, vol. 6, book 9, p. 3f). “Es gibt eine doppelte Ansicht der Verbindung des Physischen mit dem Intellektuellen. Entweder geistige und materielle Kräfte sind einander ganz ungleichartig; am Körper des Beseelten ist der Geist als ein fremdartiges Wesen gefesselt. Oder das Geistige und das Körperliche sind nicht nur mit, sondern auch durch einander.“. |

| 39 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 81). “Aber jene Grundkraft ist für uns, was die Farbe für den Blindgebohrenen, und eine Philosophie, welche diese Aufgabe a priori zu lösen sich unterfängt, ist also nicht mehr Philosophie, sondern Schwärmerei.”. |

| 40 | (Treviranus 1822, vol. 6, 1822, p. 5). “Der Ursprung allen Lebens liegt in einem Princip, dessen Wesen Selbstthätigkeit ist.”. |

| 41 | (Treviranus 1822, vol. 6, p. 13f). “Gedächtnis und Erinnerungsvermögen sind überhaupt die am weitesten in der thierischen Natur verbreiteten Seelenkräfte. Selbst die Insekten geben deutliche und zum Theil auffallende Beweise von dem Besitz derselben, wie unter andern die Bienen bey ihrer schon erwähnten Rückkehr im Frühjahr zu den Stellen, wo sie im Herbste gefüttert wurden.”. |

| 42 | (Treviranus 1822, vol. 6, p. 7f). “Man vergleiche den Affen mit dem Menschen: man lese die Nachrichten zuverlässiger Beobachter von den Geistesfähigkeiten des Orang-Outang: den Abstand zwischen diesem und dem Menschen wird man allerdings gross finden. Aber den Besitz ähnlicher, wenn auch weit mehr beschränkter, geistiger Kräfte, als dem Menschen verliehen sind, wird man dem Affen nicht absprechen können. Das Thier scheint zu suchen und zu meiden, zu begehren und zu verabscheuen, zu lieben und zu hassen, wie der Mensch. […] das Thier erinnert sich auch an Vergangenes, welches ohne Bewusstseyn der Existenz nicht möglich wäre, und handelt da, wo der Instinkt allein dasselbe nicht leiten kann, mit Ueberlegung und Wahl der Mittel, also mit Freyheit.” |

| 43 | (Treviranus 1802, vol. 1, p. 52). “dass wir den Grund des Lebens in einer Ursache suchen, die man schon in der Kindheit der Biologie mit dem Namen eines Lebensgeistes, oder Archeus ahndete. Zwar verwirft unser jetziges Zeitalter diese Ahndung, nennt sie eine hyperphysische Hypothese, und setzt an die Stelle derselben die blosse Form und Mischung der Materie. Allein jene Grundkraft ist ein hyperphysisches Wesen.” |

| 44 | (Treviranus 1831, vol. 1, p. 7). “Gehen wir jetzt zur Betrachtung unsers Gegenstandes selber über, so liegt uns zuerst die Beantwortung der Frage ob: Was eigentlich Leben ist? Wer dieses Wort ausspricht, nennet etwas Geheimnisvolles. Die Region des Lebens gränzt an die Übersinnliche Welt.” |

| 45 | (Treviranus 1831, vol. 1, p. 4f). “Alles Beobachten jener Zweckmässigkeit […] und alles Nachdenken darüber führt endlich zu einem Urgrund, der sich nur ahnen lässt. Daher waren alle, die den Erscheinungen des Lebens mit reinem Herzen nachforschten, Menschen von tiefem religiösem Gefühl. Ich erinnere nur an Swammerdam, Bonnet und Linné. Ihre Frömmigkeit trug freilich das Kleid der Erziehung und ihres Zeitalters. Aber wenn auch Swammerdam faselnd erscheint bei den theologischen Ausführungen, die er von seinen grossen zootomischen Entdeckungen machte […] wenn auch Bonnet und viele andere Naturforscher des vorigen Jahrhunderts ihre eigene Weisheit für die des Schöpfers priesen, so suchten sie doch, obwohl auf Abwegen, das höhere Licht, dessen Abglanz sie erblickt hatten.”. |

| 46 | Ibid. “Wer dieses Licht in der Natur verkennet, sieht trostlos in ihr nur einen ewigen Kreislauf von Entstehen und Vergehen. Wer träumend oder dichtend Worte sucht, die dem Licht entsprechen sollen, und damit an die Erklärung der Erscheinungen des Lebens geht, findet nicht die Wahrheit, sondern allenthalben nur seine Hirngespinste.”. |

| 47 | (Treviranus 1831, vol. 1, p. 10). “Kein zweckmässiges Wirken ist ohne ein Analogon der Vernunft denkbar. Zweckmässigkeit ist der eigentliche Charakter des Wirkens der Vernunft […] jede Lebensäusserung muss also Wirkung eines, der Vernunft ähnlichen Princips sein.”. |

| 48 | (Treviranus 1831, vol. 1, p. 1). “Der Gegenstand, worüber ich die Resultate meiner Forschungen in diesem Werke mittheilen werde, ist die Geschichte des Entstehens, Wirkens und Vergehens der lebenden Wesen und der Verhältnisse, worin sie zu einander und zur übrigen Natur, ihre einzelnen Teilen zu einander und zum Ganzen stehen.”. |

| 49 | (Treviranus 1831, vol. 1, p. 3). “Man kann sich tiefe mineralogische, chemische und physische Kenntnisse erwerben, ohne über die grossen Fragen zu reflectiren; Was, woher und wozu wir selber sind? Aber man kann nicht einmal über die Entstehung der Aufgussthierchen zur Gewissheit gelangen, ohne auf Fragen zu stossen, die sich an jene knüpfen.”. |

| 50 | (Treviranus 1831, vol. 1, p. 1). “Sich selber erkennen ist das erste Gesetz für den Weisen. Aber Niemand erkennet sich selber, so wenig dem Geiste als dem Körper nach, der sich nicht mit den ihm verwandten Wesen vergleicht.” |

References

- Anonymous. 1804. Einige Blicke in die Natur nach Sander. Graz: Widmanstätten. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhoff, Jürgen. 2009. Romantic Science and Psycology. In The Cambridge Companion to German Romanticism. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Ann, and Kaspar Von Greyerz. 2020. Physico-Theology. Religion and Science in Europe 1650–1750. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich. 1779. Handbuch der Naturgeschichte. Göttingen: Dieterich. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet, Charles. 1745. Traité D’insectologie ou Observations sur les Pucerons. Paris: Durand. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet, Karl. 1774. Betrachtungen über die Natur, 3rd ed. Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Junius. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, Tobias. 2014. Organismen. Agenten zwischen Innen- und Außenwelten 1780–1860. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, Annette. 1992. Klassifikation—System—‘Scala Naturae’. Das Ordnen der Objekte in Naturwissenschaft und Pharmazie Zwischen 1700 und 1850. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Erxleben, Johann Christian Polykarp. 1777. Anfangsgründe der Naturgeschichte. Göttingen: Dieterich. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein-Herz, Petra. 2007. Die große Kette der Wesen. Ordnungen in der Naturgeschichte der Frühen Neuzeit. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Gambarotto, Andrea. 2014. Teleology beyond Regrets: On the Role of Schelling’s Organicism in Treviranus’ Biology. Verifiche 43: 137–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gambarotto, Andrea. 2018. Vital Forces, Teleology and Organization. Philosophy of Nature and the Rise of Biology in Germany. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Carl Wilhelm. 1820–1836. Monographie der Spinnen—Monographia Aranearum. Nuremberg: Lechner. [Google Scholar]

- Hermes, Maria. 2011. Der Nachlass Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus‘ (1776–1837) und Ludolph Christian Treviranus‘ (1779–1864) in der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Bremen. Bremen: Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, Brigitte. 1983. Chemophysiologie zwischen vitalistischer und mechanistischer Biologie im 19. Jahrhundert. Medizinhistorisches Journal 18: 163–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Höxtermann, Ekkehard, and Hartmut Hilger, eds. 2007. Lebenswissen. Eine Einführung in die Geschichte der Biologie. Rangsdorf: Natur und Text. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin, Nikolaus Joseph. 1800. Anleitung zur Pflanzenkenntnis, 2nd ed. Vienna: Wappler. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, Ilse, Rolf Löther, and Konrad Senglaub, eds. 1982. Geschichte der Biologie. Theorien, Methoden, Institutionen, Kurzbiographien. Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, Thomas. 2004. Geschichte der Biologie. Die Wissenschaft vom Leben. München: CH Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Kanz, Kai Torsten. 2007. Biologie—die Wissenschaft vom Leben? Vom Ursprung des Begriffs zum System biologischer Disziplinen. In Lebenswissen. Eine Einführung in die Geschichte der Biologie. Edited by Ekkehard Höxtermann and Hartmut Hilger. Rangsdorf: Natur und Text, pp. 100–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. 1965. The Great Chain of Being. A Study of the History of an Idea, 6th ed. New York: Harper and Row. First published 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Pagel, Julius. 1894. Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold. In Allgmeine Deutsche Biographie. Leipzig: Dunker und Humblot, vol. 38, p. 588. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, John. 1744. The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation, 11th ed. Glasgow: Robert Urie, p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Reill, Peter Hanns. 2005. Vitalizing Nature in the Enlightenment. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, Heinrich. 1784. Von der Güte und Weisheit Gottes in der Natur. Frankfurt and Leipzig. [Google Scholar]

- Schelling, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph. 1798. Von der Weltseele, eine Hypothese der höhern Physik zur Erklärung des allgemeinen Organismus. Hamburg: Friedrich Perthes. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Keith. 1984. Man and the Natural World. Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800. London: Penguin, p. 165ff. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold. 1802. Biologie oder Philosophie der Lebenden Natur für Naturforscher und Ärzte. Göttingen: Johann Friedrich Röwer, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold. 1803. Biologie oder Philosophie der Lebenden Natur für Naturforscher und Ärzte. Göttingen: Johann Friedrich Röwer, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold. 1805. Biologie oder Philosophie der Lebenden Natur für Naturforscher und Ärzte. Göttingen: Johann Friedrich Röwer, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold. 1812. Ueber den Innern Bau der Arachniden. Nuremberg: Lechner. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold. 1814. Biologie oder Philosophie der Lebenden Natur für Naturforscher und Ärzte. Göttingen: Johann Friedrich Röwer, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold. 1818. Biologie oder Philosophie der Lebenden Natur für Naturforscher und Ärzte. Göttingen: Johann Friedrich Röwer, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Gottfried Reinhold. 1822. Biologie oder Philosophie der Lebenden Natur für Naturforscher und Ärzte. Göttingen: Johann Friedrich Röwer, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Reinhold Gottfried. 1831. Erscheinungen und Gesetze des Organischen Lebens. Neu dargestellt von Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus. Bremen: Georg Heyse, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus, Reinhold Gottfried. 1832. Erscheinungen und Gesetze des organischen Lebens. Neu dargestellt von Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus. Bremen: Georg Heyse, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Von Rohr, Julius Bernhard. 1745. Phytho-Theologia, Oder Vernunfft= und Schrifftmäßiger Versuch, wie aus dem Reiche der Gewächse die Allmacht, Weisheit, Güte und Gerechtigkeit des grossen Schöpffers und Erhalters aller Dinge von den menschen erkannt werden möge, Und sein allerheiligster Name hiervor gepriesen werde, 2nd ed. Frankfurt and Leipzig: Michael Blochberger. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Wilhelm Ernst. 1837. Zum Gedächtniß von Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus. At His Grave. Bremen: Georg Heyse. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, Elke. 2007. Die wechselnden Gewänder der Natur. Die Biologie nach Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus. Verhandlungen zur Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie 13: 177–85. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).