Abstract

At the eastern entrance of the Singapore Strait lies Pedra Branca, an island of granite rock situated in hazardous waters. Its unexceptional presence belies a rich cartographical history and infamous reputation for leading ships to grief since antiquity. Pedra Branca was first pushed into the spotlight when the British constructed the Horsburgh Lighthouse in 1851. It later caught international attention when a heated territorial dispute for the island between Singapore and Malaysia arose, lasting from 1979–2018, with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) eventually granting rights to Singapore. The ensuing legal battle led to renewed interest in the geography and post-19th century history of the island. The most recent breakthrough, however, provides a glimpse into an even earlier history of Pedra Branca—and by extension, Singapore—as shipwrecked remains dating from the 14th century were uncovered in the surrounding waters. Historical research on the ancient history of Pedra Branca has been mostly neglected by scholars over the years; thus, this paper aims to shed some light on this enigmatic history of the island and at the same time establish its history and significance by utilizing pre-British-colonization historical cartographical data from as early as the 15th century.

1. Introduction

To anyone not privy to the history and significance of the island, Pedra Branca, previously referred to as Pulau Batu Puteh by Malaysia, might seem like just another trivial piece of guano-covered rock among thousands in the Malayan archipelago. However, the island has an abundantly rich history dating back to ancient times—once another nautical hazard to ships navigating tempestuous waters and now embroiled in an increasingly protracted and heated political territory dispute between Singapore and Malaysia at the turn of the 21st century. As the island is referred to by different names—‘Pedra Branca’ by Singapore and ‘Pulau Batu Puteh’ by Malaysia—the island will henceforth be referred to in this paper as ‘Pedra Branca’, its current official name.

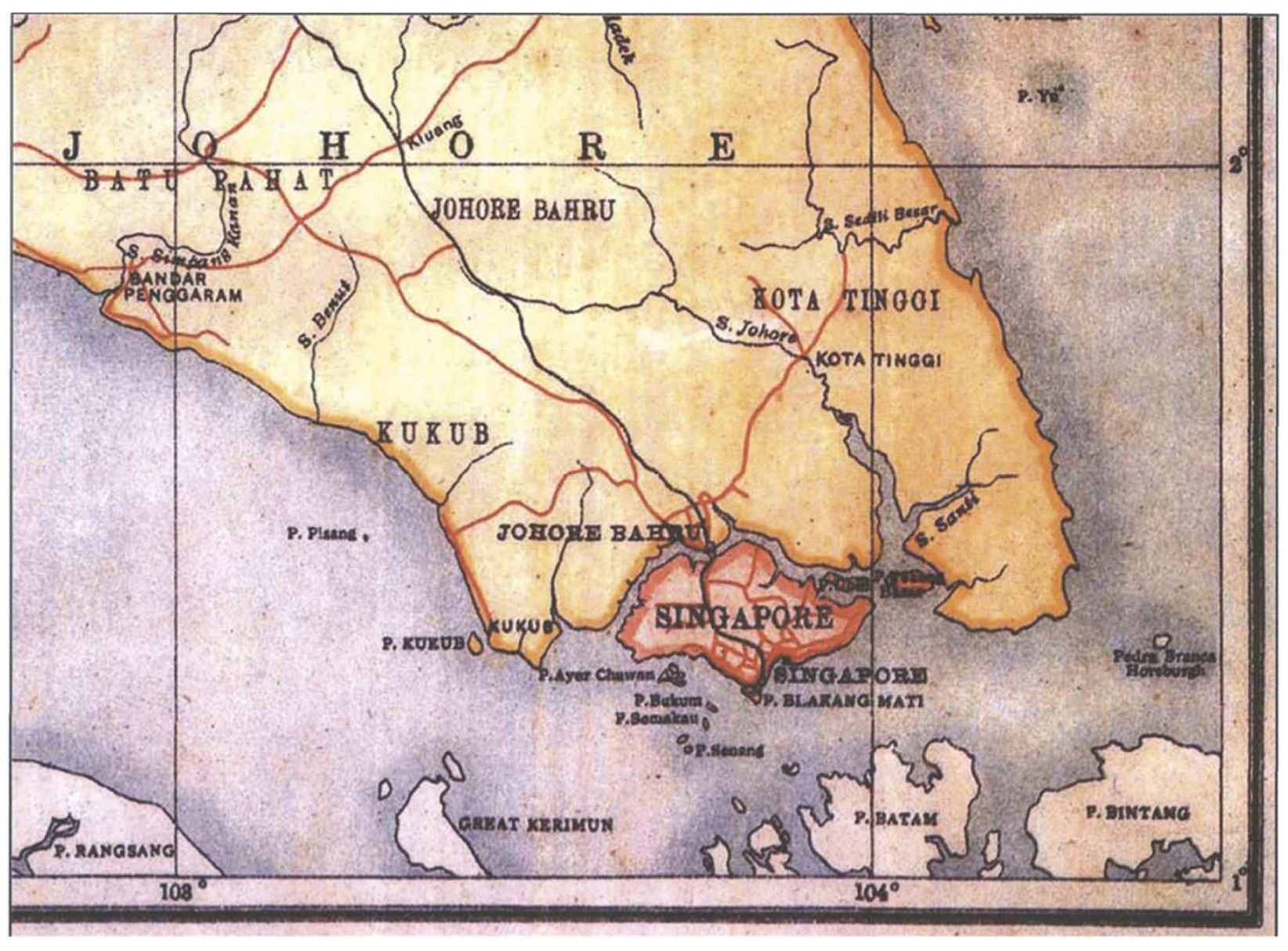

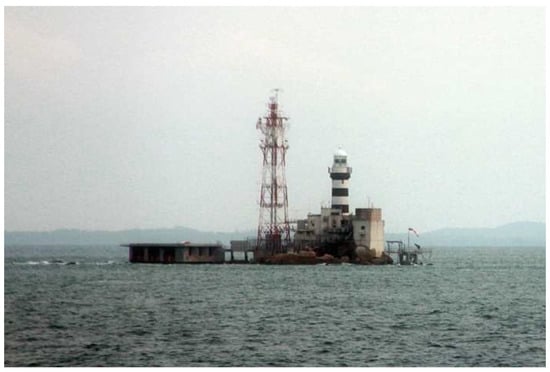

The island is located along the Straits of Singapore, at 01°19′49″ N 104°24′21″ E, approximately 24 nautical miles (or 44.45 km) east of mainland Singapore (refer to Figure 1) [1]. It is surrounded by a few other small rocky islands—Middle Rocks and South Ledge. The island houses the Horsburgh Lighthouse, first lit in 1851 [2] during British colonial rule by government surveyor and engineer John Turnbull Thomson [3]. Today, Pedra Branca boasts a heliport and modern radar technology [2,4].

Figure 1.

Modern mapped location of Pedra Branca in the South China Sea, in relation to surrounding countries [5].

2. Background and Motivation

Pedra Branca, an uninhabited rock for much of its history, was thrust into the spotlight when a heated territorial dispute arose in 1980 after Malaysia published a map establishing its ownership of the island. Singapore, in turn, refused to accept this sudden claim. This political dispute prompted an escalation to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), with lawyers and personnel from both sides delving into historical archival records and documents linked to Pedra Branca from Malaya’s peri- and post-colonial past in hopes of substantiating their sovereignty rights.

Maps from the peri- and post-colonial era were extensively collated and later published by the ICJ in official documents pertaining to the dispute [6,7]. However, pre-colonial maps were briefly discussed, if not neglected, because Pedra Branca’s post-colonial status was more relevant to the dispute. The final judgment rendered by the ICJ saw Singapore officially granted the sovereignty of Pedra Branca on 23 May 2008, 29 years after the initial controversy began [8].

After the ruling, interest in the history and geography of the island began to wane; that is, until the intriguing discovery in 2015 of 14th century AD shipwrecked ancient Chinese artifacts 100 m northwest of Pedra Branca [9,10]. The most prominent archaeological findings include Longquan greenware dishes and bowls as well as an unprecedented number of blue and white Yuan dynasty porcelain pieces, more than any found in the history of recorded shipwrecks [9]. This solidified the theory that Singapore was already a popular port of call and trading hub, even before British colonization in 1819.

It is important to note that the knowledge of Singapore’s pre-colonial history is severely lacking, particularly due to a lack of documentation and an apparent gap in history that has not been reconciled. When Sir Stamford Raffles landed on Singapore in search of a strategic trading port in the region for the British, he described Singapore as sparsely populated—mainly inhabited by some Chinese planters, a few Malays, and a small number of aborigines [11]. The knowledge of the prior inhabitants appears to have been lost with time. Artifacts such as the still-undeciphered Singapore Stone have remained enigmatic as the attributed civilization and language inscribed on the stone still elude the understanding of historians [12,13]. The latest shipwreck discovery has proven to be an exciting progression in Singapore’s archaeology and has reignited interest in the ancient history of Singapore and its territories. The Singapore Government has also begun to express an unprecedented level of interest in research on the subject as well as the preservation of the ever-growing trove of historical artifacts found in Singapore and her territories. Legally, Singapore’s National Heritage Board (NHB) Act is slated for review to provide a proper legal framework to protect these historical findings [14]. Further excavation and expeditions have been conducted and planned by the Singapore Government to explore current known shipwrecks and potentially detect other potential remnants [9,10].

As such, this paper aims to understand the significance of Pedra Branca in the ancient world. The next section, Section 3, will delve into Pedra Branca’s historical impact and progression from a small inconsequential guano-covered island to a crucial landmark of cartographical navigation in the ancient world. The etymology of the island’s name will be studied by utilizing methods of comparison between the pre-colonial maps of the region from the 13th to 18th century AD. Section 4 will outline the building of the historic Horsburgh Lighthouse, an important structure that made navigation through the area much safer and accessible for incoming vessels and ships. From dispute to resolution, Section 5 will look at the nature of the territorial conflict of the island between Singapore and Malaysia and how it, in its process, enriched our knowledge of the historical cartography of the island. Lastly, Section 6 will provide concluding remarks and provide a summarized review of the findings.

3. Ancient Beginnings: Singapore and Pedra Branca

Near the peak of the so-called last ice age, 18,000 years ago, geographers believe coastal regions like the Singapore Strait and parts of the South China Sea, in which Pedra Branca is situated, consisted of broad river valleys and large coastal plains. As the ice gradually melted, sea levels rose, reaching their current levels 6000 years ago and forming the Singapore Strait [6].

Pedra Branca is one of the many rocky landmarks found within the waters of the Singapore Strait. It is fairly small, though sizable in comparison to the other surrounding rocks—around 8560 square meters (92,100 square ft) during low tide. Multiple records have mentioned this rocky island, dating back to the mid-17th century, with maps clearly detailing the island and its surrounding rugged terrain. The existence of such records intrigued scholars due to the island’s size, the lack of significant landmarks or inhabitation, and taking into account Singapore’s scarce historical data during the pre-colonial period of its history.

Significant challenges were faced by historians while trying to piece together Singapore’s early history as they had to rely on brief, partial, and often contradictory accounts of historical events, people, or locations written in these records. One fact is certain—Singapore was an important trading city and essential port for a large portion of its history since the late 13th century, in large part thanks to the country’s prime location, making it an important pitstop for ships traveling along the Asian sea routes [15]. However, little is known about historical events and the general life of the people living in the country. There is no clear indication of whether events recorded in surviving documents were simply folktales, actual occurrences, or partial and/or exaggerated recounts [16]. A popular example of one such historical document is the Malay Annals (Malay: Sejarah Melayu) [17,18,19]. Composed around the 15th or 16th century, and with at least seven known versions [16], it is a work of historical literature that was written in the narrative-prose form. The Malay Annals detail the history of Malacca from the mid-13th century, up to the demise of the Malacca sultanate (refer to Figure 2) in the 1511 Portuguese conquest of Malacca [19]. The contents, though an undoubtedly valuable resource to historians, were written from a skewed perspective and romanticized to glorify the Malay maritime empire and the reign of its sultans [20]. Additionally, the stories were highly symbolic and consisted of fictional scenarios and mystical beings.

Figure 2.

The extent of the Malacca Sultanate in the 15th century [23].

Singaporeans today are most familiar with one of the stories from the Malay Annals: the famed legend of Singapore’s founding [19] (pp. 40–45). The narrative depicts Sang Nila Utama, a Srivijayan prince who stumbles upon the island of ‘Temasek’ [21] (p. 84), which is now modern-day Singapore. He coined the term ‘Singapura’, translating to ‘Lion City’ in Sanskrit (Siṃhápuram), after sighting a lion roaming the island. He was subsequently coronated and reigned over the island as the first Rājā of the Kingdom of Singapura, a monarchy that lasted up to the late 14th century. The Kingdom of Singapura then transitioned into the Malay maritime empire, and the Malacca Sultanate was established. This prosperous 15th century (1400–1511) trading empire spanned across most of the Malay Peninsula, thriving on international maritime trade.

Another popular legend is that of Badang [19] (pp. 53–63), [22], a strongman who, in an attempt to win a competition of strength, threw a gigantic stone into the Singapore River. The legend goes that the stone thrown by Badang corresponds to the Singapore Stone in its full form before it was blown up by the British in 1843. The story of Badang follows his accidental trapping of a demon who was trying to steal his fish. In exchange for its release, the demon agreed to grant Badang his request for superhuman strength. With his newfound ability, he was able to defeat the other strongmen in tests of strength. Besides his competitive ventures, he often used his abilities for good deeds, leaving behind a legacy as a noble and legendary figure.

A book by the Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires, ‘Suma Oriental que trata do Mar Roxo até aos Chins’ (The Suma Oriental, an account of the East, from the Red Sea to China) [24] (pp. 229–289), written between 1512–1515 in Malacca and India, is the earliest known European document describing the Malay Archipelago. The book contains extensive records obtained from his firsthand observations as well as detailed accounts from residents, all of which cover a diverse range of historical, economic, commercial, geographical, and ethnographic information. Singapore (Singapura) was briefly mentioned as one of Malacca’s neighboring lands [24] (p. 262). This marks the first known occurrence of the form spelled as ‘Singapura’ in Portuguese sources, which retains in the present day as the modern Portuguese form.

Pedra Branca in particular, though not a subject of these historical legends and sources, was however mentioned in multiple historical accounts and marked in ancient cartographical maps as a crucial landmark of maritime navigation around the Malay Peninsula.

3.1. Ancient China

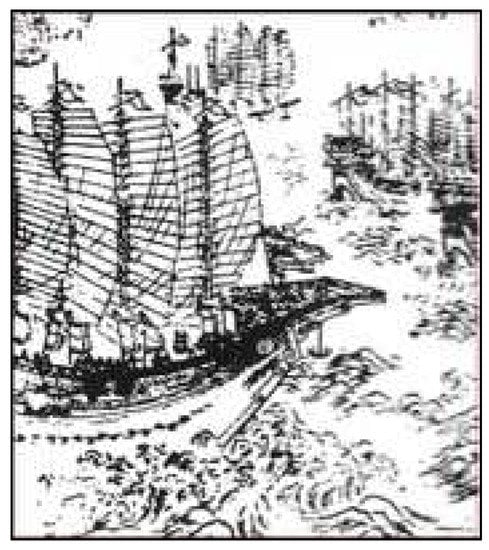

One of the most ancient records of Pedra Branca came from the maps and documents of Chinese Imperial Admiral Zhèng Hé (郑和; Wades–Giles spelling system: Cheng Ho) of the Ming Dynasty in the early 15th century. Zhèng Hé’s ocean expeditions were known to be one of the most impressive feats of sea exploration of all time [25]. The Yongle emperor of the Ming dynasty (reign 1402–1424) ordered these missions to demonstrate the Ming dynasty’s prowess, technological advancements, and thriving economy [26,27]. Zhèng Hé’s men brought valuable and exclusive gifts such as porcelain, silk, and tea on these trips to impress key personnel and rulers of regions beyond China. Each expedition was grandiose, with hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of sailors commanded by Zhèng Hé (depicted in Figure 3). There was a total of seven voyages (c. 1405–1433), and the first trip alone had three hundred and seventeen ships, sixty of which were large and majestic, with intricate and extensive floors and staterooms [26,28]. This momentous feat was unrivaled up to World War I, a fact that has marveled modern historians.

Figure 3.

Chinese woodblock print representing Zhèng Hé’s ships [33].

On top of the size of the fleets, Zhèng Hé’s travels also reached an impressive distance for its time. Passing through multiple continents and regions, from India to Southeast Asia and even Africa in the final three voyages, he also made multiple return trips to Southeast Asia and along the Straits of Malacca [25,27]. His trips coincided with the period of the founding of the first Malay State—the Sultanate of Malacca—and the rise of Muslim influence in the region [29]. Zhèng Hé himself was chosen as ambassador on these trips as he was well-versed in Islam, having been born to a Muslim family [26].

Despite the grandeur of his achievements, the reactions of the Chinese people were mixed. The financial decision by Yongle to commission these trips brewed discontent amongst commoners. Subsequent emperors also succeeded in destroying most of Zhèng Hé’s legacy by minimizing the importance of his voyages, as seen by how Chinese Imperial records of Zhèng Hé appeared to be incomplete and sometimes erroneous, with significant parts omitted [28].

However, Zhèng Hé was and is still revered as a legendary and godly figure in some parts of Southeast Asia, including Singapore. In the last few decades of the Ming dynasty, Chinese naval troop officer Máo Yuányí ‘茅元儀’ [30] compiled a comprehensive military book the Wǔbèizhì (武備志; translation: ‘Treatise on Armament Technology’ or ‘Records of Armaments and Military Provisions’), an encyclopedia of military affairs of ancient China—maps, detailed drawings of firearms and artillery, as well as fighting styles and formations. Although the book was dated more than 200 years after Zhèng Hé’s death, the maps drawn up by his men contributed greatly to its cartographical data.

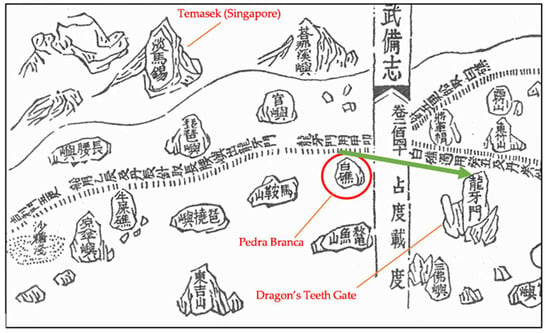

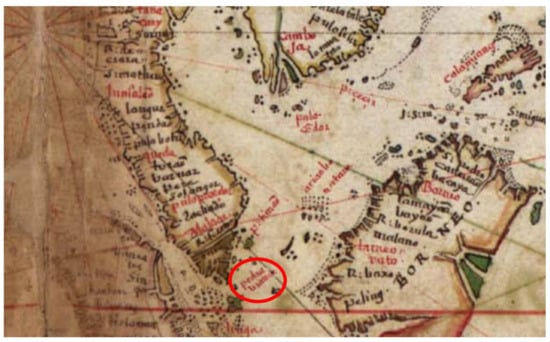

On his journey along the Straits of Malacca, Zhèng Hé’s map (refer to Figure 4) listed several landmarks such as Singapore, written as Dānmǎxī: 淡馬錫, a Chinese transliteration of Temasek [31] (p. 128), as well as Pedra Branca. Pedra Branca was marked as Báijiāo: ‘白礁’ (‘white reef’). The Chinese etymology appears to be very similar to the origins of the current name ‘Pedra Branca’, coined by the Portuguese and directly translated as ‘white rock’ when the Portuguese discovered the island in 1511. The white color of the rock could be in reference to the white guano-covered surface of the island deposited by the sea birds [32].

Figure 4.

Zhèng Hé’s map from Wu bei Zhi [34].

Zhèng Hé’s maps also provided clear instructions for seafarers to safely navigate the waters of the Malay Peninsula and steer clear of the dangerous rocks, which included Pedra Branca [30]. In ancient times, people relied heavily on cartography and astronomical information from prior travelers to navigate the seas. Data provided were very precise as any mistakes or miscalculations could at best be an inconvenience, and at worst, lead to fatal consequences. Historian and anthropologist Dr Julian Davison [32] provides a translated version of the navigation instructions provided by Zhèng Hé:

“Zhèng Hé inform us that after leaving Lun Ya Men (Dragon’s Teeth Straits)—the narrow channel between Sentosa and Singapore island, which was the preferred route for Chinese mariners rounding the bottom of the Malay Peninsula—one should steer a course between 75° to 90° for five watches until the ship makes Bai Jiao (White Rock). One should then set a new course of 25° followed by 15° for another five watches, until one comes abreast of East Bamboo Mountain—one of the two peaks on Pulau Aur”.[32] (p. 86)

3.2. Portuguese and Dutch Empire

About a century after Zhèng Hé’s travels, the Portuguese landed in Singapore and its surrounding region. Their colonization was quick, and their stronghold on Malacca lasted for more than a century. Unlike the friendly diplomatic interactions by the Chinese with the leaders of the region, the Portuguese came to inflict fear and subjugate the natives. Their hatred for the Muslim population fueled their cruelty and the Portuguese colonization was characterized by brutality and the decimation of populations in Asia [35,36]. Strategic Portuguese general Afonso de Albuquerque was powerful and widely feared, known as ‘the Terrible’ or ‘the Great’ [36]. Albuquerque conquered Goa, India, in 1510, which became the main base and capital of the Portuguese Empire of the East.

Soon after, Malacca caught his attention with its reputation as a thriving trading center and port of the Indian Ocean trade. He stated that Malacca was the “center and terminus of all the rich merchandise and trades (…) source of all the spices”, [36]. In 1511, he finally seized the sultanate of Malaka and took control of Malaka, which included Singapore and Pedra Branca. According to Subrahmanyam [27], an unnamed Malay document from the late 17th or early 18th century depicts the arrival and seizure of Malaka from then sultan Ahmad Syah, making him the last sultan of the Malaccan sultanate, reigning from 1511–1513. The Portuguese (Franks) successfully appeased the sultan through offers of valuable gifts and offer of friendship. However, the Portuguese secretly turned on the Malakan people, stealthily preparing cannons and muskets, bombarding the people at midnight, destroying their homes and fort, and causing the sultan to flee. It also outlines how the Portuguese utilized the trading port and built the A Famosa ‘fortress of Malaka’ under the command of Albuquerque, a section of which still stands in Malacca today.

During the Portuguese empire’s stronghold on Malaka, they sailed past the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, discovering Pedra Branca, a rock covered by the white excrements deposited by a specific breed of bird—the black-naped tern, many of which appeared to have settled and nested extensively on the rock (refer to Figure 5 for an early 19th-century depiction). The Portuguese named the rock ‘Pedra Branca’, meaning ‘white rock’ in the Portuguese language, in reference to this unique and prominent feature [32].

Figure 5.

Pedra Branca before the building of Horsburgh Lighthouse [37].

A puzzling fact about the name of the island is that the prior maps of Zhèng Hé also referenced Pedra Branca as a ‘white rock’ in the Chinese written language. It is probable that the Portuguese may have already been aware of Pedra Branca and the dangerous terrain before catching sight of it. Pedra Branca’s white exterior was likely to have been a clear landmark for ancient cartographers to mark the location of the hazardous and rocky waters on the south of the Singapore Strait. However, this was definitely not a well-known fact to most. Most of the other European powers did not have sufficient knowledge of the cartography of the region [32].

Pedra Branca was also mentioned in some Portuguese sources from the early 16th century. One such document is ‘The Book of Francisco Rodrigues’ [24] (pp. 290–305), written before 1515 by the Portuguese pilot and cartographer, and translated by the editor from the Portuguese MS in the Bibliothèque de la Chambre des Deputés, Paris. Pedra Branca was briefly mentioned in his navigation guide from Malacca to China:

“From Malacca to Pulo Param it is five jãos, and from there to Pisang (Piçam) another five, and from Pulo Pisang to Karimun (Caryman) it is three jãos, and from Karimun to Singapore it is five, and from Singapore to Pedra Branca five, and from [Pedra Branca to] Pull Tingi (Tymge) five jãos to the north-east…”.[24] (p. 301)

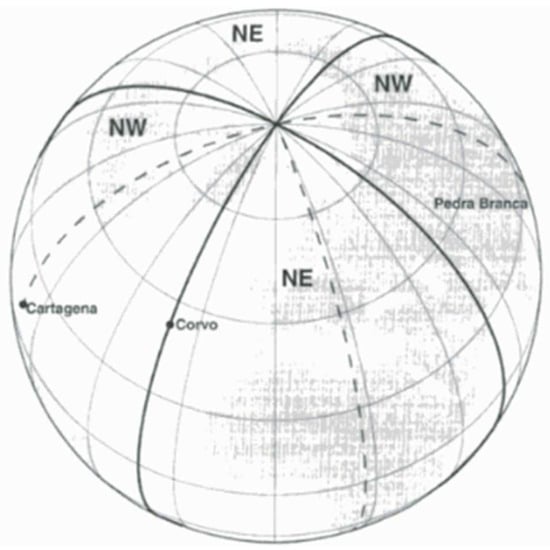

Besides Pedra Branca’s landmark navigation uses, Portuguese navigators appear to also have believed Pedra Branca to be one of few important places where the magnetic and true north coincided [38] (p. 54), as shown in Figure 6. This was during a period when navigators were beginning to hypothesize the concept of magnetism and its effect on sea navigation and positioning.

Figure 6.

Earth’s orthographic projection by Da Costa in the late 16th century [38] (p. 54).

Up to the end of the 16th century, the Portuguese kept detailed sea maps of the area under maximum secrecy. These maps were not allowed to be spread or exposed to their rivals, mainly the other European powers seeking trade opportunities in the Far East and with an ambition to challenge the Portuguese’s stronghold in the area. Seafarers had to be specially granted permission to the maps from the Portuguese royal library and immediately return the map upon arrival. Anyone caught smuggling the classified maps would face summary execution. This proved to be a strong deterrent as the information remained hidden for an impressive 90 odd years. The information was finally exposed by Dutch trader Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, a secretary of the archbishop of Goa [32]. During his time in Goa from 1583 to 1588, he painstakingly transferred the map information, replicating maps by hand and logging crucial nautical data for navigation. In 1595, he published Reys-gheschrift vande navigatien der Portugaloysers in Orienten (Travel Accounts of Portuguese Navigation in the Orient) and Itinerario in 1597 [39,40]. He documented the Portuguese secret navigational records and included personal experiences from his own voyagers. His works were hugely popular in Europe and played a key role in exposing the Portuguese’s vulnerabilities, allowing the Dutch to infiltrate the Portuguese’s iron grip on the region [39,41]. Itinerario, in particular, was translated to English, Latin, and French soon after its release. It references Pedra Branca, highlighting the dangers faced by ships traveling to and from China:

“From the Cape of Singapura to the hook named Sinosura to the east, are 18 miles; 6 or 7 miles from there lies a cliffe in the sea called Pedra Bianque, or White Rock, where the shippes that come and goe from China doe oftentymes passe in greate danger and some are left upon it, whereby the Pilots when they come thither are in greate feare for other way than this they have not.”[42] (p. 119)

After Jan Huygen’s books were published, multiple historical European maps began to contain Pedra Branca as a landmark [32]. The frequency of Pedra Branca’s inclusion even in full maps covering the entirety of Asia was remarkable, especially considering its small size and lack of human activity.

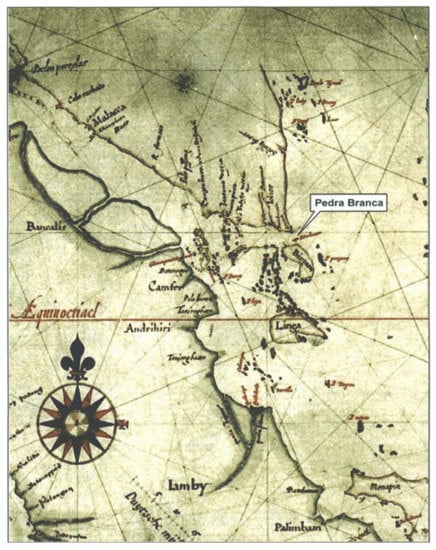

In an early map (Figure 7) from the early 17th century produced by Hessel Gerritz, a cartographer of the Dutch East India Company, Pedra Branca is clearly marked as ‘Pedrablanca’ off the Johor coast [6].

Figure 7.

Dutch East India Company. Map of Sumatra 1 [6,43] (p. 136).

An ancient map from the Portuguese Empire dates to 1630 (Figure 8). This map was produced close to the period of relative obscurity in Singapore’s history (1620–1819) after the Dutch gained power in the region and before British colonization. The map shows ‘Pedra Branca’, the name consistent with its modern form. It is insightful that Pedra Branca was not forgotten even during this period of history.

Figure 8.

Extract: Portuguese map of Asia [44].

A British map from 1727 “A Map of the Dominions of Johore and of the Island of Sumatra with the Adjacent Islands” (Figure 9) is showing the island of “Pedrobranco” and was drawn by Scottish sea captain Alexander Hamilton. The map depicts “Pedrobranco” alongside the “Romano” islands, near the Johor coast and located north of the ‘Straits of Governdore’ [6].

Figure 9.

Extract: Alexander Hamilton, Dominions of Johore [6,45] (p. 139).

This 1755 map (Figure 10) shows a detailed cartographical depiction of Singapore and the Malaka Strait by Jacques Nicolas Bellin, the then head of the French Hydrographic Office. Singapore is depicted as Pulo or Isle Panjang, while Pedra Branca is very clearly indicated as ‘Pierre Blanche’.

Figure 10.

Map of Singapore and the Malaka Strait [46].

3.3. Dangers of the Region in the Modern World

Even up to today, the dangers of the surrounding waters still pose a challenge to modern vessels. According to the book ‘The Road to the World Court’ [7], on 15 October 1988, Shunmugam Jayakumar, then Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore and Counsel for the Singapore legal team in the Pedra Branca territorial dispute, conducted a visit to the island as part of the legal preparations. On the journey, a large storm hit, causing the ropes on the lifeboat to break and smashing the crockery on board. The experienced crew managed to tide through the storm and the huge crashing waves. However, a separate fishing boat that sailed concurrently unfortunately perished in that same storm.

This incident showed that despite the advancements in technology and the future erection of a lighthouse on Pedra Branca, the dangers were greatly reduced but not completely gone, as ships still face challenges navigating the waters in modern times. This further proves the extreme conditions in the regions and the difficulties ships in the ancient world had to face without current modern advancements and improvements made to the area to assist these vessels.

4. The Horsburgh Lighthouse

Multiple historical records have attested that the rock–reef area surrounding Pedra Branca was fraught with peril. Shipwrecks were a common occurrence and ships had to be extra cautious when crossing these waters. At high tide, Pedra Branca would be assessed by sailors as largely innocuous, looking like a clear and avoidable bundle of rocks. This appearance is deceiving, however, as the low tide would reveal random detached rocks littering the area, some as far as 100 feet away from Pedra Branca [3]. From 1824 to 1851, during the period of British colonization, records show that at least 25 decently size vessels faced major issues while navigating the area, resulting in issues from minor strandings to major wrecks on Pedra Branca [3,7].

These dangers presented themselves long before the 19th century, with ships in the ancient world coming to grief in the region as well. The need to warn and guide sailors was a likely reason for Pedra Branca’s inclusion in many ancient maps. Unfortunately, records of shipwrecked accounts in the region are sparse. Though there are documented accounts, for a long time, there was a lack of archaeological evidence of these wrecks. This changed in 2014, with the breakthrough discovery of the first ancient shipwreck found near Pedra Branca. Excavations were completed in 2019, lasting a total of five years. Archaeologists date the shipwreck to the 14th century, around the Yuan Dynasty, before the Ming Dynasty and the time of Zhèng Hé [9]. Artifacts such as Yuan dynasty porcelain pieces, Chinese Longquan greenware, and a Chinese seal, among other miscellaneous contents, were uncovered. Impressively, many of the delicate porcelain items remained mostly intact despite laying on the seabed for 700 years [9]. These findings further solidified Singapore’s role as a trading port even during a time when historical records of Singapore were lacking and supports the ancient accounts of the treacherous region around Pedra Branca.

This major issue came to the attention of the British after they successfully colonized Malaya. Having a personal stake in the successful international trade in the port of Singapore, the British recognized the need to erect a lighthouse in these perilous waters. The strategic relevance of Pedra Branca became less of that of merely a rock in the sea, but its relational aspects extended to be a source of economic power for the British through the control of maritime trading [47]. After years of deliberation, the project was commissioned to English architect and engineer John Turnbull Thomson in 1847 and the finalized spot of the lighthouse was settled on Pedra Branca. The granite masonry lighthouse was to be named after honored hydrographer Captain James Horsburgh of the East India Company, who played a large role in helping the British to gather charting and directional information in the East during the late 18th century.

4.1. Building Process, Challenges, and Completion

Construction of the lighthouse lasted from 1850 to 1851, the process filled with its fair share of trials and tribulations. Thomson recounts the process in depth in his journals, extracts, and paintings published by his great-grandson John Hall-Jones in his book ‘The Horsburgh Lighthouse’ [3]. The book is one of the most comprehensive sources on the lighthouse and will be the main source of reference in the following paragraphs describing the lighthouse, its conception, and its construction.

Initial issues came when Thomson failed to secure laborers at the start, eventually having to settle on Chinese stone-breakers at the Pulau Ubin quarry who were cutting and dressing granite blocks for the lighthouse. The first major challenge arose as the workers were successfully transported to Pedra Branca, but food and provisions did not arrive. This became a dire situation, and an urgent rescue mission was conducted. Heaviness of the rock’s surf made docking particularly difficult. The ship had to be anchored by an expert swimmer of the Orang Laut (The Orang Laut are a nomadic ethnic group of seafarers living around the Malay Peninsula, Singapore, and the Indonesian Riau Islands [48,49]. They played a major role during the Srivijayan Empire, the Sultanate of Malacca, and the Sultanate of Johor, engaging in sea-related occupations and warding off piracy on the seas [50]. ‘Orang Laut’ or the alternative name ‘Orang Selat’ translates to ‘Sea People’ in Malay. The Europeans adapted the term ‘Orang Selat’ into the term ‘Celates’ in reference to the Orang Laut people. Orang Laut was referenced by Portuguese sources as well, with Pires describing Singapore as unremarkable and populated by ‘a few Celeste villages’ [24] (p. 262).) tribe a ways from the rock. The men had to be tied and hauled on board, leaving them agitated. The return journey through the rocks was also challenging and terrifying for the workers. Thomson struggled to motivate and convince the workers to continue and return to the rock, having to keep a keen lookout and prevent the workers from escaping.

On the next trip, a diverse group of workers was brought on to the project. Hired by contractor Choa-ah-Lam, the workers consisted of a mix of Chinese, Hindoo, and Malay members, all of which Thomson lambasts to be people chosen out of the ‘dregs of the population’ [3] (p. 20), often opium smokers, convicts, and murderers. More issues arose when the construction was underway. There was a need to build shades and provide an excessive amount of water to the workers due to the grueling heat which he stated caused ‘the skin to peel off the face and other exposed parts of the body, the lips to crack, the perspiration to flow and created a thirst that only large draughts of water could allay, an element we had only a precarious supply of’ [3] (p. 20).

Next came riots as the Chinese workers attempted to forcefully board the boat meant to bring the visiting Choa back to Singapore. This led to a rampage and the Chinese, armed with bricks, were ready to fling them at the boat’s crew. Thomson stopped the fights before they could escalate by arresting the aggravated members. In an effort to quell the riots, he reminded the workers of the agreements made to complete their duty at Pedra Branca as well as threatening punishments such as flogging to those who continued to make attempts to escape. The workers did not stage another riot afterward. Additionally, it was later revealed that the workers had numerous grievances about them not being paid by Choa, which could have led to their reluctance. Choa readily absconded soon after he was exposed, escaping on a ship to China. Subsequently, Thomson paid the workers personally and their morale went up; he stated that they became ‘obedient and tractable as they had formerly been fractious’.

Another issue that came up was when the crew of the patrol ship Nancy, sent as a replacement to the prior ship, decided to stage a mutiny due to a fear for their own safety after facing a storm in the waters. This posed a problem as the ship was the main source of firewood and water for the team on Pedra Branca. The crew would not be swayed despite Thomson’s encouragements and the crew had to be discharged and replaced. The heat also affected Thomson’s health as he suffered from heat exhaustion that lasted for years. His condition eventually kept him from ever returning to Singapore, despite a strong desire to do so, and he instead settled in New Zealand.

Upon completion of the lighthouse, a foundation stone was laid by Thomson. Under the stone laid a copperplate with the following inscription:

“In the Year of our Lord 1850andIn the 13th year of the Reign ofVictoriaQueen of Great Britain and Ireland,The Most NobleJames Andrew Marquis of Dalhousie, K.T.being Governor-General of British India,The Foundation Stone,of the Light-house to be erected at Pedra Brancaand dedicated to the Memory of the CelebratedHydrographer James Horsburgh, F.R.S.was laid on the 24th day of May, the anniversaryof the Birth-day of Her Most Gracious Majesty,by theWorshipful Master M.F. Davidson, Esq.,and theBrethren of the Lodge Zetland in the EastNo. 748.In the presence of the Governor of the StraitsSettlements and many of the British and Foreign Residents of SingaporeJ.T. Thomson,Architect.”[3,51]

4.2. Legacy and Changes

2021 marks exactly 170 years since the lighthouse was first lit in 1851, making the Horsburgh Lighthouse Singapore’s oldest lighthouse. The lighthouse has made the waters in the area much safer to navigate and has been a central landmark in maritime navigation in the Singapore Strait. It is also symbolic of Singapore’s status as a maritime nation thriving on international trade and commerce since ancient times [52].

According to the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore [2], the Horsburgh Lighthouse, as seen in Figure 11, is currently equipped with new high-tech equipment and functions, which include LED marine lanterns driven by sustainable solar energy and a transmitter to send signals to the radars of nearby ships. Before the lighthouse was constructed, there were no records or mentions of inhabitants on the island. After the lighthouse was built, however, facilities were also added so the staff manning the lighthouse can now reside on the island [7] (p. 6).

Figure 11.

Photograph of modern Pedra Branca and the Horsburgh Lighthouse (‘Pedra Branca and Horsburgh Lighthouse’ by Seloloving is released under CC BY-SA 4.0).

5. The Pedra Branca Malaysia-Singapore Dispute

5.1. Nature of Dispute

The importance of the island lies in its strategic location on the eastern part of the Singapore Strait. The country that controls the island would have the ability to control and monitor maritime shipping in the eastern entrance of the Straits [4]. After the dissolution of the British Crown Colony of Singapore in 1963 after 144 years of British rule, Singapore, together with the Crown Colonies of North Borneo and Sarawak, merged with the Federation of Malaya to form Malaysia.

However, due to strong political and economic differences between mainland Malaysia’s and Singapore’s ruling parties, tensions led to the eventual separation of Singapore from the rest of Malaysia on 9 August 1965, only 23 months after the original union [53]. Though this separation was clear and officially recognized by both countries and by the United Nations [54], Pedra Branca’s location made the sovereignty and ownership of the rocky island less transparent.

Considering the richness of Pedra Branca’s cartographical history, it is not surprising that the territorial issues first arose due to a map published by Malaysia on 21 December 1979. The map, titled ‘Territorial Waters and Continental Shelf Boundaries of Malaysia’, claimed the island of Pedra Branca to be within the territorial waters of Malaysia [7,55]. Singapore rejected this claim on 14 February 1980 via a diplomatic note to Malaysia requesting for the information to be corrected. Bilateral negotiations were conducted, with the other two surrounding rocky areas—Middle Rocks and South Ledge—being put up for territorial debate as well [55]. Despite mutual effort and attempts in resolving the dispute from 1993 to 1994, it was to no avail. In view of these fruitless attempts, both parties agreed to sign a Special Agreement on 6 February 2003 to legally settle the sovereignty dispute through the ICJ on 24 July 2003 [7].

5.2. Singapore’s Case

Singapore argued that the legal status of Pedra Branca was that of terra nullius, meaning ‘land belonging to no one’ in Latin. In international law, the concept is used to justify a claim that a territory is acquired by a state’s occupation of the land [7,56,57]. For example, during the period of the colonial empires, colonial powers could claim regions as terra nullius upon the discovery of the land [58,59,60]. Using the terra nullius argument, the Singapore legal team argued that post-colonial rule, it had been ‘acting as a country that had sovereignty on the island’ [7] (p. 11), but that Malaysia, conversely, had not exercised such sovereignty.

Additionally, multiple historical documents, prior cartographical data, and meteorological studies were published by Malaysia in the past attributing Pedra Branca to Singapore [7] (p. 11). This included an important 1953 letter correspondence between J D Higham on behalf of the Colonial Secretary to the British Advisor, Johor, and M Seth Saaid, then acting Secretary of Johor. The Singaporean legal team argued that these documents provided clear evidence that Johor officials did not claim Pedra Branca as a Malaysian territory [7,56].

5.3. Malaysia’s Case

According to the ‘Memorial of Malaysia’ regarding the case [6], Malaysia’s legal team argued that Malaysia had an original title to Pedra Branca of long standing [61]. This is in reference to the claim that before 1824, the islands in and around the area of the Singapore Strait belonged to the Sultanate of Johor, the predecessor of Malaysia. Additionally, historical records showed that the British had consistently recognized the sovereignty of the Sultanate, solidifying Malaysia’s argument.

As a rebuttal to Singapore, Malaysia also stated that terra nullius did not apply to Pedra Branca as the island was utilized by the Malays, who were under the rule of Johor, for activities such as fishing. Malaysia also presented evidence of the English East India Company seeking permission from the Sultan and Temenggong, chief of public security of Johor, to build the Horsburgh Lighthouse. As such, Malaysia claims they have the original title, and therefore sovereignty, over Pedra Branca. Malaysia’s argument also relied heavily on historical cartographic evidence.

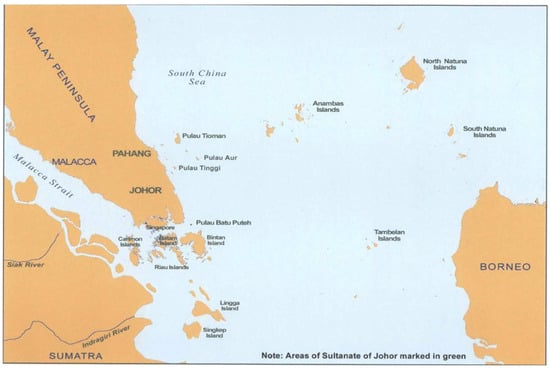

The map in Figure 12 shows the land belonging to the Sultanate of Johor before 1824, consisting of full or partial sections of the Malay Peninsula, Singapore, Sumatra, and Borneo, as well the islands situated on the Strait. The Malaysian team used this as their main argument, justifying Malaysia as the original titleholder to Pedra Branca [6].

Figure 12.

Sultanate of Johor Prior to 1824 [6] (p. 18).

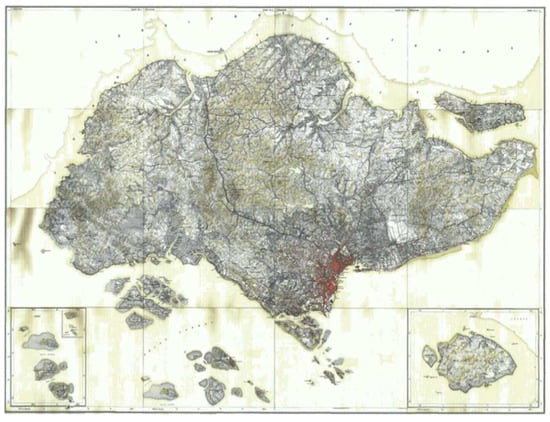

The Malaysian legal team shared a 1924 map drawn up by the Surveyor-General of the Federated Malay States and the Straits Settlements (Figure 13). The team pointed out the lack of inclusion of Pedra Branca, Middle Rocks, or South Ledge either in the main maps or the double insert provided, suggesting that the islands were not considered Singapore’s dependencies [6].

Figure 13.

Map of Singapore with Island, including insets [6,62] (p. 142).

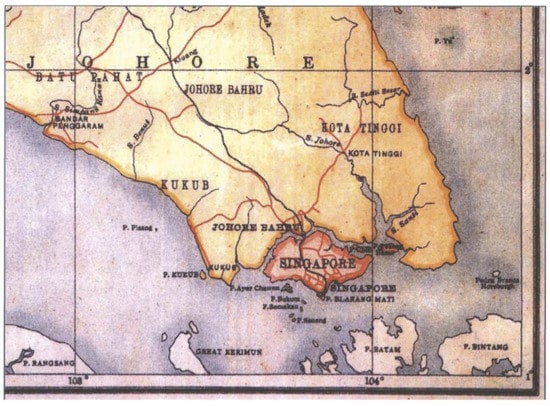

Figure 14 contains a 1925 colonial map, the Straits Settlements were colored in red. The Malaysian legal team argued that Pedra Branca is not colored in red on the map, as compared to other well-established Singaporean islands like Pulau Ubin, and thus Pedra Branca was not considered part of the Straits Settlements of Singapore [6].

Figure 14.

Map of Malaya [6,63] (p. 144).

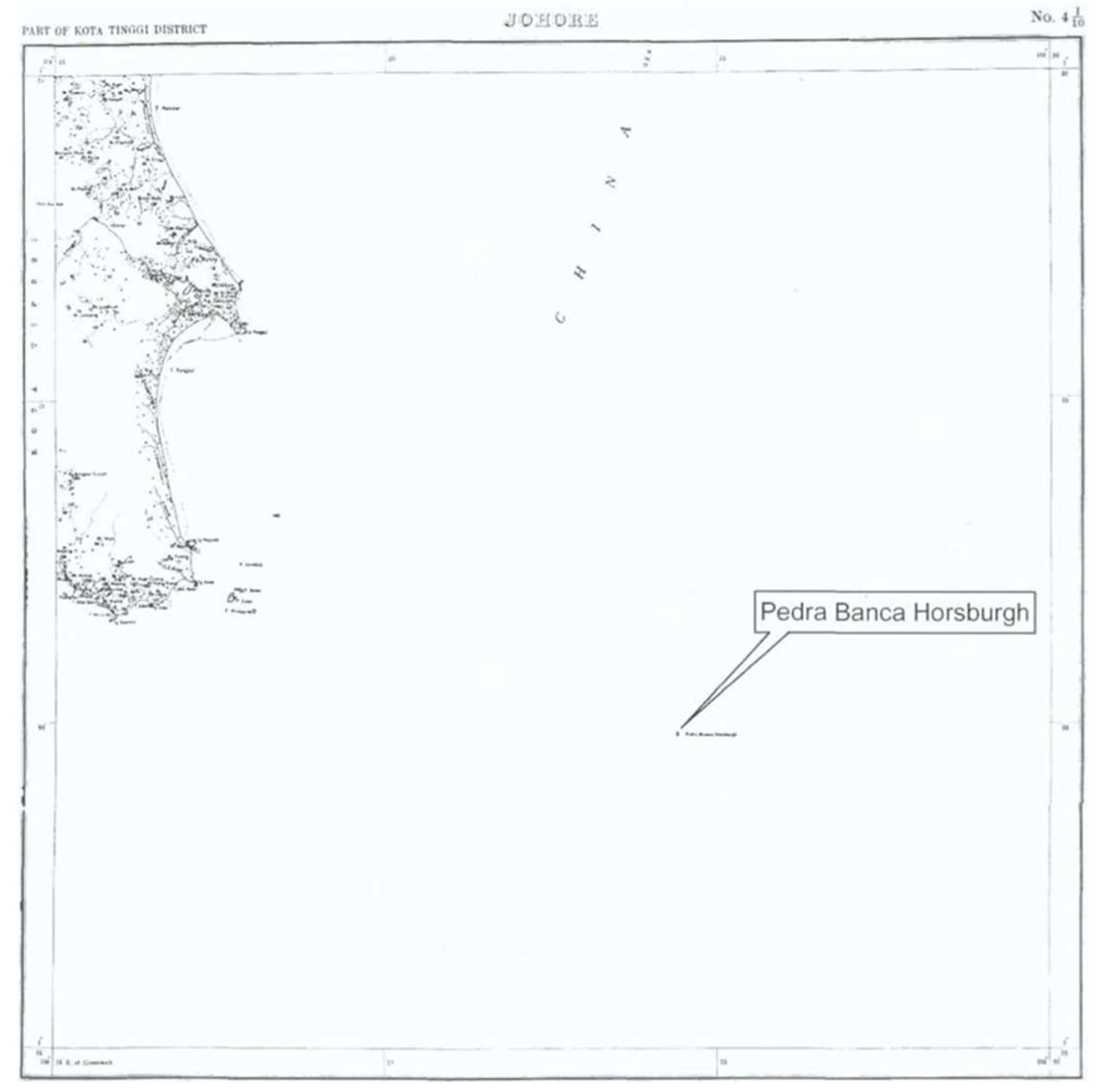

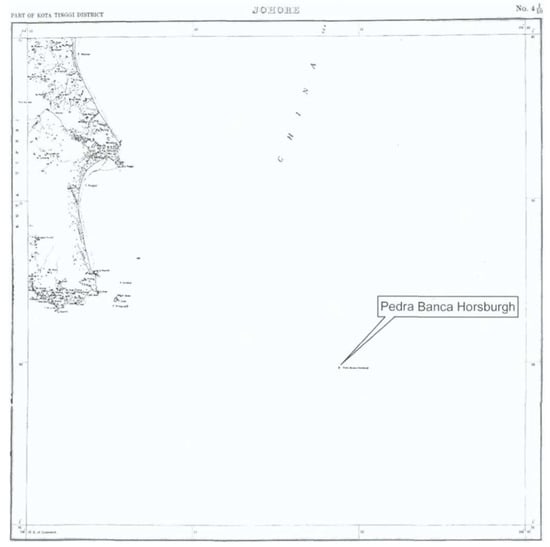

Another map (Figure 15) provided by the team was a map created by the Johor Sultan Ibrahim in 1926, which lists Pedra Branca in the section of the map named “Part of Kota Tinggi District, Johore,” stating that Pedra Branca was part of Johor, a part of modern-day Malaysia, and not Singapore [6].

Figure 15.

Johore, Part of Kota Tinggi District [6,64] (p. 145).

5.4. ICJ’s Decision

The ICJ indeed ruled that all evidence pointed to the sultan of Johor having had original title to Pedra Branca and other islands in the Straits of Singapore. This decision came as there was no evidence of any completing claim during the sultan’s rule. Additionally, the sultan had authority over the Orang Laut people of the sea, who partook in activities and tasks in the sea of the Straits of Singapore. The ICJ found that the sultan of Johor had sovereignty of Pedra Branca as of 1844, the period when the British prepared for the building of the lighthouse. However, Singapore had provided evidence of its subsequent unrefuted and uncontested acts of sovereignty of the island, as well as presenting the past official documents by Malaysian authorities confirming that Singapore indeed had sovereignty over Pedra Branca [55].

The ICJ thus ruled that ‘by 1980 sovereignty over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh had passed over to Singapore’. The conclusion was thus that Singapore had sovereignty over the island [55]. After this 2008 ruling, Malaysia, under the Najib Razak administration, had expressed intentions of appealing this ruling. An appeal application was made in 2017 but was withdrawn after Najib was defeated in the May 2018 Malaysian elections. With a 10-year ICJ statute for application for reviews on the ruling and a decision to recognize Singapore’s sovereignty by then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in 2019, the matter appeared to be finally put to an end. However, in October 2021, the Malaysian Cabinet once again decided to form a panel to study its options regarding the ruling by the ICJ [65].

6. Conclusions

This paper studies the pre-British historical impact of Pedra Branca in ancient Malacca (before Singapore’s independence), extending to China and the international maritime trade. Five ancient maps from ancient empires and civilizations explicitly marked the island of Pedra Branca in their maps, in varying forms. Methods of historical cartographical analysis were employed, with cross-comparison between maps and their accompanying navigational instructions and descriptions. These maps date back to the 15th to 18th century, before the British colonization of the Malaysian Peninsula, giving us a glimpse into the ancient past of the island; a period when information about the history of Singapore was not well documented.

Evidence shows that the island’s name remained largely consistent throughout all records, with the name represented with the sense of ‘white rock’ in its various forms and languages. This could be suggestive of extensive knowledge of Pedra Branca and the general region long before the earliest documented maps of the area were published. However, any such records could have been merely transmitted orally or lost in the passage of time. Without relevant supporting evidence, absolute conclusions on the origins of the name cannot be ascertained. However, it is also impossible to rule out the possibility of coincidental naming conventions from the travelers of different ancient empires, named in reference to the island’s white guano-filled exterior and rocky base.

To explore the geographical significance of the island’s name [66] (passim), this paper delves into the widespread ancient records of the dangers faced by ships traveling through the surrounding including and surrounding Pedra Branca, described since the 15th century as perilous and requiring extreme precision to navigate safely. In 2015, shipwrecked remains of ancient 14th-century Chinese ships were discovered around the waters of Pedra Branca, providing rare archaeological evidence of these ancient, documented wrecks. The dangers led to the construction of the Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca, commissioned by the British during the regional rule of the British Empire and which became an integral part of Pedra Branca’s history. Multiple challenges were faced in the building process, in large part due to the aforementioned dangers of the surrounding waters.

Finally, the paper looks at the territorial dispute of the island between Malaysia and Singapore. Both legal teams dug up historical records in an avid attempt to defend their claims on their sovereignty of the island. Malaysia, in particular, relied heavily on historical cartography to defend their argument that they lay claim on the island based on ‘original title’. Some pre-colonial maps were produced, while multiple colonial and post-colonial maps were also presented. Though the ICJ court eventually granted Singapore sovereignty of Pedra Branca in 2008, the cartographical findings have proven to be of immense value in the study of Pedra Branca’s significance and legacy in history.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P.C. and B.O.M.Q.; Writing—original draft, B.O.M.Q.; Writing—review & editing, F.P.C. and B.O.M.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs Singapore. Pedra Branca. Available online: https://www.mfa.gov.sg/SINGAPORES-FOREIGN-POLICY/Key-Issues/Pedra-Branca (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore. Horsburgh Lighthouse. Available online: https://www.mpa.gov.sg/assets/mpa25/horsburgh_lh.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Hall-Jones, J. The Horsburgh Lighthouse; Self Published: Invercargill, New Zealand, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.L.; Tan, X.L.; Teng, S.M.L. Case Study on the Dispute over Pedra Branca; Nanyang Technological University: Singapore, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jappalang, Pedra Branca Map. 2008, A Map Showing the Approximate Location of the Island of Pedra Branca, Which Is under the Sovereignty of Singapore, at the Eastern End of the Singapore Strait Where It Meets the South China Sea. Near It Are the Maritime Features Middle Rocks (under Malaysian Sovereignty) and South Ledge, and the Coasts of Johor, Malaysia, and Bintan, Indonesia. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pedra_Branca_Map.svg (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Mohamad, A.K. Case Concerning Sovereignty over Pedra Branca Pulau Batu Puteh. Middle Rocks and South Ledge; International Court of Justice: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, S.; Koh, T.T.B. Pedra Branca: The Road to the World Court; NUS Press: Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius-Takahama, V. Pedra Branca. Available online: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_722_2005-01-20.html (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Chew, H.M. Pedra Branca Shipwrecks: How Singapore Divers Chanced upon Centuries-Old Artefacts Underwater. Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/pedra-branca-shipwrecks-how-singapore-divers-chanced-upon-centuries-old-artefacts-underwater-2030201 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Sahni, A. Sunken Treasures Found in Singapore’s Waters. Available online: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-07-26/Sunken-treasures-found-in-Singapore-s-waters-12cVPBGa3u0/index.html (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Santhi, S.; Saravanakumar, A. The Economic Development of Singapore: A Historical Perspective. Aut Aut Res. J. 2020, 11, 441–459. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius-Takahama, V. Singapore Stone. Available online: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_43_2005-01-26.html (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Chua, S.H. Crypto-Linguistics in Singapore: Deciphering the Singapore Stone; Nanyang Technological University: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Protection for Artefacts Still to Be Found. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/st-editorial/protection-for-artefacts-still-to-be-found (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Tan, J. Port of Singapore. Available online: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2018-04-20_085007.html (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Roolvink, R. The variant versions of the Malay Annals. Bijdr. Tot De Taal Land En Volkenkd. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Southeast Asia 1967, 123, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, C.C. The Malay Annals. J. Malay. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 1952, 25, 5–276. [Google Scholar]

- Winstedt, R.O. The Malay Annals of Sejarah Melayu. J. Malay. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 1938, 16, 1–226. [Google Scholar]

- Leyden, J. Malay Annals: Translated from the Malay Language; Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown: London, UK, 1821. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, Y.F. A History of Classical Malay Literature/Liaw Yock Fang; Bahari, R.; Aveling, H., Translators; Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perono Cacciafoco, F.; Shia, D. Singapore Pre-colonial Place Names: A Philological Reconstruction Developed through the Analysis of Historical Maps. Rev. Hist. Geogr. Toponomast. 2020, 15, 79–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.; Tan, A.Y.P.; Lim-Yang, R. Attack of the Swordfish and Other Singapore Tales; National Heritage Board: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kartapranata, G. The Historical Map of Malacca Sultanate (1402–1511) Malay Peninsula and East Coast of Sumatra. 2011, The Historical Map of Malacca Sultanate (1402–1511) Malay Peninsula and East Coast of Sumatra. Made and Improved Based on “Atlas Sejarah Indonesia dan Dunia” (The Atlas of Indonesian and World History), PT Pembina Peraga Jakarta 1996. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Malacca_Sultanate_en.svg (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Pires, T.; Rodrigues, F. The Suma Oriental of Tome Pires and The Book of Francisco Rodrigues; Cortesao, A., Ed.; Asian Educational Services: New Delhi, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brezina, C. Zhèng Hé: China’s Greatest Explorer, Mariner, and Navigator; Rosen Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gronewald, S. The Ming Voyagers. Available online: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/china_1000ce_mingvoyages.htm (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Subrahmanyam, S. The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500–1700: A Political and Economic History; Longman: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W. Maritime Asia: Admiral Zhèng Hé’s Voyages to the “West oceans”. Educ. About Asia 2014, 19, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hrubý, J. Establishing a Common Ground—Admiral Zhèng Hé as an Agent of Cultural Diplomacy in Malaysia. In Transnational Sites of China’s Cultural Diplomacy; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Máo, Y.; Wu, B.Z. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g7821rm.gct00058/?sp=14&r=-0.743,0.44,2.486,1.099,0 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Perono Cacciafoco, F.; Gan, C. Naming Singapore: A Historical Survey on the Naming and Re-Naming Process of the Lion City. An. Univ. Din Craiova Ser. Ştiinţe Filol. 2020, 42, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, J. Between a Rock and a Hard Place. Expat 2008, 86–94. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20081001162749/http://www.theexpat.com/magazine/July08_086_PedraBranca.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Anonymous. Chinese Woodblock Print, Representing Zhèng Hé’s Ships (中国木板画所刻郑和号). Early 17th century. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ZhengHeShips.gif (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Máo, Y. Treatise on Armament Technology or Records of Armaments and Military Provisions (Wu Bei Zhi; 武備志). 1621. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2004633695/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Diffie, B.W.; Winius, G.D. Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Franz-Stefan, G. How Portugal Forged an Empire in Asia. Available online: https://thediplomat.com/2019/07/how-portugal-forged-an-empire-in-asia (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Daniell, T.; Daniell, W. Pedra Branca, Straits of Malacca. 1820, An Etching of Pedra Branca before the Building of Horsburgh Lighthouse, with Dark Storm Clouds in the Background. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PedraBranca-Daniell-c1820-detail.jpg (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Jonkers, A.R.T. Earth’s Magnetism in the Age of Sail; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Koeman, C. Jan Huygen Van Linschoten; UC Biblioteca Geral: Coimbra, Portugal, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kamps, I. Jan Huyghen Van Linschoten. In Travel Knowledge: European “Discoveries” in the Early Modern Period; Kamps, I., Singh, J.G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha, A. The Itineraries of Geography: Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s “Itinerario” and Dutch Expeditions to the Indian Ocean, 1594–1602. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2011, 101, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Linschoten, J.H.; Burnell, A.C. (Eds.) The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies: From the Old English Translation of 1598. The First Book, Containing His Description of the East. In Two Volumes Volume I; Hakluyt Society: London, UK, 1885. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritz, H. Map of Sumatra. 1620, Detail of a “Map of Sumatra” showing the island of “Pedrablanca” (Pedra Branca) by Hessel Gerritz, a cartographer of the Hydrographic Service of the Dutch East India Company. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hessel_Gerritsz,Map_of_Sumatra_showing_Pedra_Branca_(1620).jpg (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- De Ataide, J.; Teixeira, J. 1630 Portuguese Map of Asia. Taboas Geraes de Toda A Navegação 1630, 1630 Portuguese Map of Asia, Entitled Taboas Geraes de Toda a Navegação, Divididas e Emendadas por Dom Ieronimo de Attayde com Todos os Portos Principaes das Conquistas de Portugal Delineadas por Ioão Teixeira Cosmographo de Sua Magestade, anno de 1630 (General Tables of All the Navigation, Divided and Corrected by D. Jeronimo de Ataide, with all the Ports and Conquests of Portugal Delineated by Joao Teixeira, Cosmographer of His Majesty, Year 1630. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portuguese_map_of_Asia,_1630.jpg (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Hamilton, A. A Map of the Dominions of Johore and of the Island of Sumatra with the Adjacent Islands. 1727, Detail of Alexander Hamilton’s “A Map of the Dominions of Johore and of the Island of Sumatra with the Adjacent Islands” Showing the Island of “Pedrobranco” (Pedra Branca). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:PedraBranca-MapofDominionsofJohore-Hamilton-1727.jpg (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Bellin, J.-N. Jacques-Nicolas Bellin Map of the Straits of Malacca. 1755. Available online: https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/geo-graphic-celebrating-maps-and-their-stories/story (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Rîșteiu, N.T.; Creţan, R.; O’Brien, T. Contesting post-communist economic development: Gold extraction, local community, and rural decline in Romania. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliner, K.; The-Mulliner, L. Historical Dictionary of Singapore; Scarecrow Press: Metuchen, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sather, C. The Orang Laut; Academy of Social Sciences in cooperation with Universiti Sains Malaysia, Royal Netherlands Government: Penang, Malaysia, 1999.

- Barnouw, A.J. Cross Currents of Culture in Indonesia. Far East. Q. 1946, 5, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.T. Account of the Horsburgh Light-house. J. Indian Archipel. East. Asia 1852, 6, 427–428. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.T. Forum: Build Replica of Horsburgh Lighthouse to House a Maritime Museum. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/forum/forum-build-replica-of-horsburgh-lighthouse-to-house-a-maritime-museum (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Chee, C.H. Singapore’s Foreign Policy, 1965–1968. J. Southeast Asian Hist. 1969, 10, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Agreement Relating to the Separation of Singapore from Malaysia as an Independent and Sovereign State. 1965. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20563/volume-563-I-8206-English.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- United Nations. 168. Case Concerning Sovereignty over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore). In Summaries of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders of the International Court of Justice 2008–2012; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, T. Case Concerning Sovereignty over Pedra Branca I Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore); International Court of Justice: Singapore, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, S. Oral argument by Prof S. Jayakumar, Deputy Prime Minister, Co-ordinating Minister for National Security and Minister for Law of the Republic of Singapore. Available online: https://www.mfa.gov.sg/Newsroom/Press-Statements-Transcripts-and-Photos/2007/11/OralArgumentByProfSJayakumarDeputyPrimeMinisterCo-ordinatingMinister-press-200711-13 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Banner, S. Why Terra Nullius? Anthropology and Property Law in Early Australia. Law Hist. Rev. 2005, 23, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borch, M. Rethinking the origins of terra nullius. Aust. Hist. Stud. 2001, 32, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, B.; Heath, M. Savagery and Civilization:From Terra Nullius to the ‘Tide of History’. Ethnicities 2006, 6, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Passing of Sovereignty: The Malaysia/Singapore Territorial Dispute before the ICJ. Hague Justice J. 2008, 3, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surveyor General of the Federated Malay States. Map of Singapore with Island, Including Insets. 1923–1924, p. 142. Available online: https://www.icj-cij.org/public/files/case-related/130/14139.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Surveyor General of the Federated Malay States. Map of Malaya. 1925, p. 144. Available online: https://www.icj-cij.org/public/files/case-related/130/14139.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Ibrahim, A.-M. Johore, Part of Kota Tinggi District. 1926, p. 145. Available online: https://www.icj-cij.org/public/files/case-related/130/14139.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Teoh, S. Malaysia to Study Options on Pedra Branca, 13 Years after ICJ Decision to Award It S’pore. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysia-looking-into-reviving-pedra-branca-claim (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Creţan, R. Toponimie Geografica Geographical Toponymy; Editura Mirton: Timişoara, Romania, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).