Spirituality and Conflict in Healthcare: The History of the Canadian Baptists and Medical Mission in Orissa, 1900–1970

Abstract

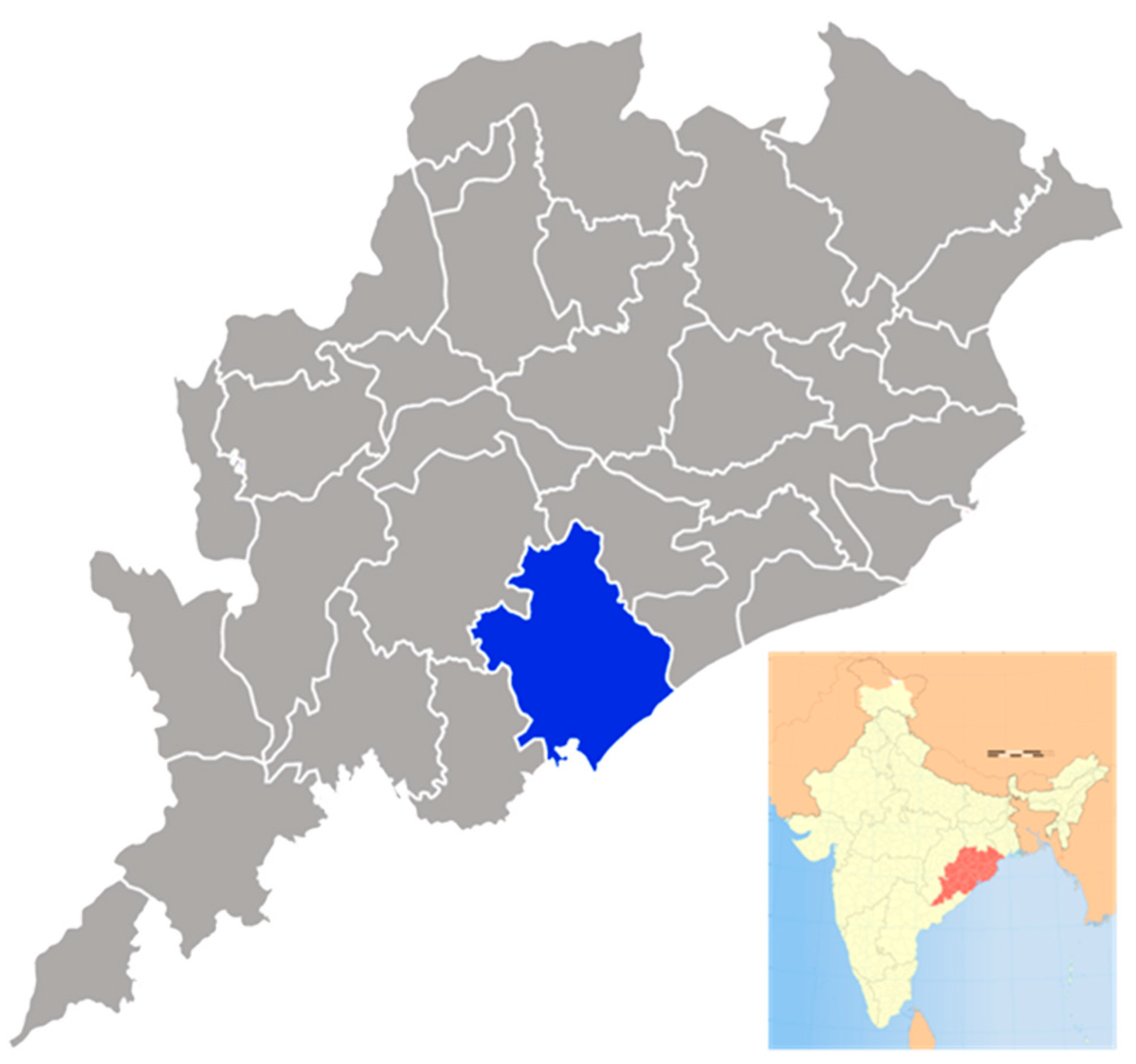

:1. Medical Mission in India and Abroad

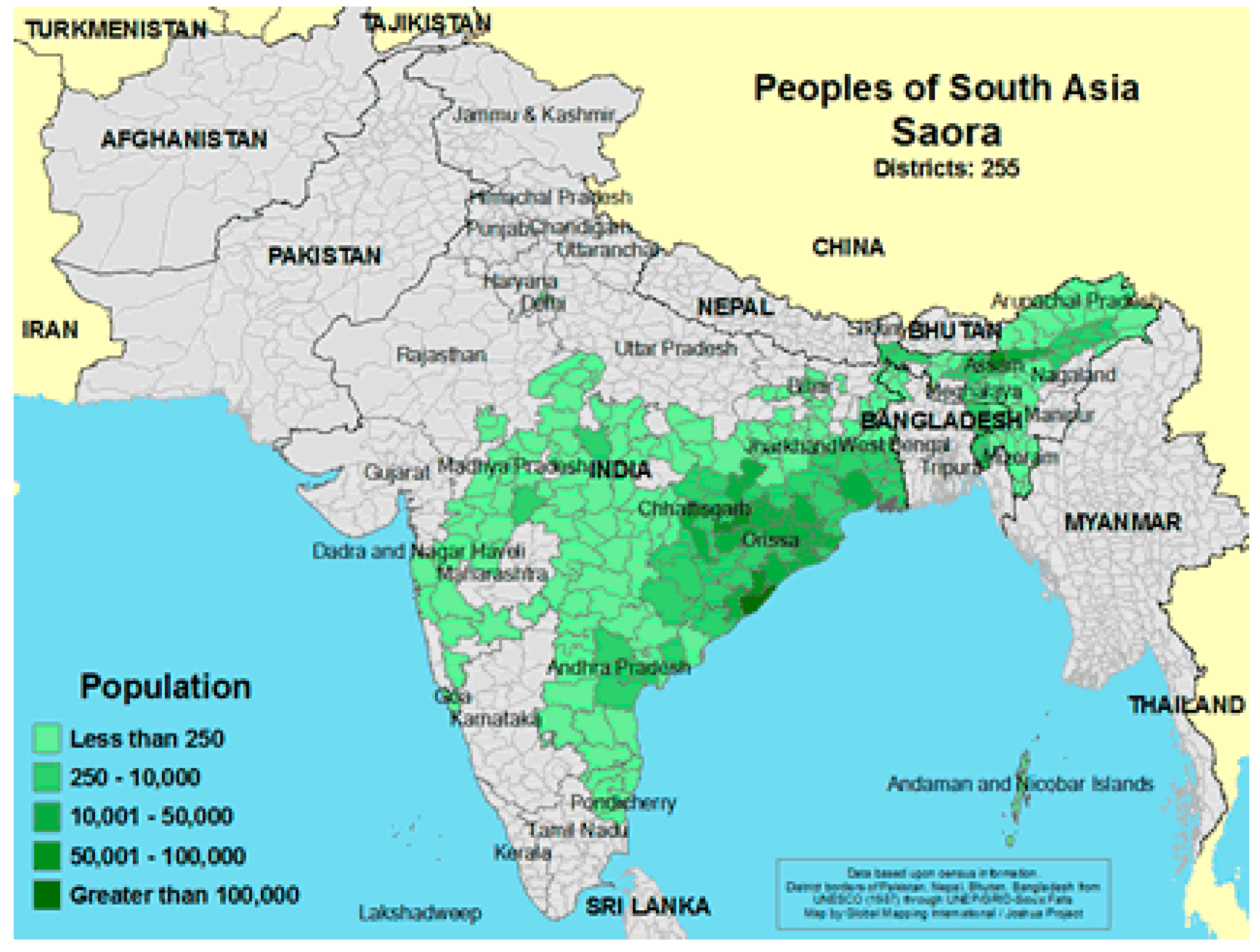

2. Brief History of Christianity among the Savaras in Ganjam (Orissa)

3. Healing the Tribal Savaras: Canadian Baptists and the Medical Mission

4. Changing Lifestyle through Health Care among the Savaras

5. Political Turmoil and Issues of Conflict: A Brief Study

“It was just before Christmas, many of our Christian villages were plunged into trouble and terror. Hostile Paiks (another Hindu group) shrewdly incited the pagan Savaras in the hill origin, arousing them to fierce antagonism against the whole Oriya Christian community. The Savaras began by cutting a rice harvest of the Christmas in different places and taking it by force. It created real conflict between the Savaras and the Oriya Christians, thousands of Savaras came to attack with bows and arrows, axes, knives and lathi”.[9] (pp. 27–30)

“…. whole villages were looted and burned and the inhabitants driven out. What pitiful stories we heard of those days of flight, little children separated from parents, people escaping from the Savaras to run into another land, women and girls snatched and torn by their ears, noses and neck”.[96]

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, D. Medical history: British India, the dutch indies and beyond. J. Asiat. Soc. 2021, 62, 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W. A Medical Missionary You’ve Never Heard of- But Should. 2020. Available online: https://www.medicalmissions.com/resources/23999/medical-missionary (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Gnanaraj, J.; Rhodes, M. Surgical work in medical missions: Study in remote areas of India. Christ. J. Glob. Health 2014, 1, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Guangqiu, X. The impact of medical missionaries on Chinese officials. J. Presbyt. Hist. 2019, 97, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Latourette, K.S. A History of the Expansion of Christianity. Volume IV, The Great Century A.D. 1800–A.D. 1914: Europe and the United States of America; Harper and Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, C.M. Does the divine physician have an unfair advantage? Healing and the Politics of conversion in twentieth century India. In Asia in the Making of Christianity: Conversion, Agency and Indigeneity, 1600s to Present; Fox, R., Fox, Y., Seitz, J.A., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Calvi, R.; Mantovanelli, F.G. Long Term Effects of Access to Health Care: Medical Mission in Colonial India. Available online: fmwww.bc.edu/EC-P/wp883.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Grundmann, C. Proclaiming the gospel by healing the sick? Historical and theological annotations on medical mission. Int. Bull. Mission Res. 1990, 14, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, R. ‘Clinical Christianity’: The Emergence of Medical Work as a Missionary Strategy in Colonial India. In Health, Medicine and the Empire: New Perspectives on Colonial India; Biswamoy, P., Harrison, M., Eds.; Orient Longman Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D. Probing History of medicine and public health in India. In Medical Encounters in British India; Kumar, D., Basu, R.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D. Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India; University of California Press: Berkeley, LA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti, T.; Chakravarti, R. An Illustrated ophthalmic register of an Arogyasala in Serfoji II’s (1798–1832) Thanjavur: An emblem of plural medical practices. J. Asiat. Soc. 2021, 62, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Basu, R.S. Introduction. In Medical Encounters in British India; Kumar, D., Basu, R.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Worsley, P. Non-Western Medical Systems. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 1982, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Gupta, S. Environmental change, health and disease in Bengal’s western frontier: Chotanagpur between 1800–1950s. J. Asiat. Soc. 2021, 62, 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, W.A. Scottish Protestant-Trained Medical Missionaries in the Nineteenth Century and Rise of the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, 2010. Available online: http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2272/1/2010duffmlitt.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- McKerrow, J. History of the Foreign Missions of the Secession and United Presbyterian Church; Andrew Elliot: Edinburgh, UK, 1868. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, J. The Story of the Rajputana Mission; Morison and Gibb Ltd.: London, UK, 1894. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, J. A History of Missions in India; Oliphant Anderson and Ferrier: London, UK, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Warneck, G. Outline of a History of Protestant Missions from the Reformation to the Present Time; Oliphant Anderson and Ferrier: Edinburgh, UK, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Melby, M.K.; Loh, L.C.; Evert, J.; Mora, G.B.; Lasker, J.; Woodmansey, K.; Adyatmaka, I.; Seymour, B. Beyond Medical “Missions” to Impact-Driven Short-Term Experiences in Global Health (STEGHs): Ethical Principles to Optimize Community Benefit and Learner Experience. Acad. Med. 2018, 30, 1–6. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christopher-Prater-2/publication/285585065_Beyond_Medical_Missions_to_Impact-Driven_Short-Term_Experiences_in_Global_Health_STEGHs_Ethical_Principles_to_Optimize_Community_Benefit_and_Learner_Experience/links/5eb6a0bd92851cd50da3af51/Beyond-Medical-Missions-to-Impact-Driven-Short-Term-Experiences-in-Global-Health-STEGHs-Ethical-Principles-to-Optimize-Community-Benefit-and-Learner-Experience.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, A. Science and philanthropy in a colonial state: Reviewing the intervention of Rockefeller Foundation in Bengal. J. Asiat. Soc. 2021, 64, 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin, P. Death by Migration: Europe’s Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Headrick, D. The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, W. Annals of the Free Church of Scotland 1843–1900; T&T Clarke: Edinburgh, UK, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Taneti, J.E. Canadian Baptist missionaries and the British raj. Bapt. Quart. 2014, 42, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B. The Bible and the Flag: Protestant Missions and British Imperialism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries; Apollos: Leicester, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D. Imperial Medicine and Indigenous Societies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman, D. Healing Bodies, Saving Souls: Medical Missions in Asia and Africa; Rodopi: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman, D. Missionaries and their Medicine: A Christian Modernity for Tribal India; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, M. Public Health in British India: Anglo-Indian Preventive Medicine 1859–1914; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, A. Religion versus Empire: British Protestant Missionaries and Overseas Expansion, 1700–1914; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman, D. Healing, medical power and the poor: Contests in tribal India. Econ. Pol. Wkly. 2007, 42, 1404–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, S. Public Health Policy and the Indian Public: Bengal, 1850–1920; Vision Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. Medicine and the Raj: British Medical Policy in India 1835–1911; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, P. Imperialism and Medicine in Bengal A Socio-Historical Perspective; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pati, B.; Harrison, M. (Eds.) Health, Medicine and Empire: Perspectives on Colonial India; Orient Longman Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Padel, F. The Sacrifice of Human Being: British Rule and the Konds of Orissa; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, A. Their Footprints Remain: Biomedical Beginnings Across the Indo-Tibetan Frontier; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, M. Curing their Ills; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D. Introduction: Tropical medicine before Mansion. In Warm Climates and Western Medicine: The Emergence of Tropical Medicine 1500–1900; Arnold, D., Ed.; Rodopi: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, N. Contagious and Enclaves: Tropical Medicine in Colonial India; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beidelmann, T. Social theory and the study of christian missions in Africa. J. Int. Afr. Inst. 1974, 44, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.S. Healing the Sick and the Destitute: Protestant Missionaries and Medical Missions in 19th and 20th century Travancore. In Medical Encounters in British India; Deepak, K., Basu, R.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New Delh, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, S. Forms of knowledge in early modern Asia: Introduction. Comp. Stud. South Asia Africa Middle East 2004, 24, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carder, W.G. 1951. Serango: The Saoras: General Work, Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1950; Canadian Baptist Mission Archives: Hamilton, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, G. Development of Railway Transport in Colonial Orissa (1854–1936). Orissa Rev. 2008, 43–45. Available online: http://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/2008/jan-2008/engpdf/43-45.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Hunter, W.W. Orissa Vol. 1; Smith, Elden and Co.: London, UK, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Agriculture Department, Agriculture Information Unit, Small Farmers Development Agency: District, Ganjam; Government of Orissa: Orissa, India, 1972.

- Chaudhuri, B.B. Towards and understanding of the tribal world of Colonial Eastern India. In Narratives from the Margins: Aspects of Adivasi History in India; Guppta, D.S., Basu, R.S., Eds.; Primus Books: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, S.K. Indian Culture and Personality: Saora Highlanders of Eastern Ghats; South Asia Books: New Delhi, India, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McLaurin, M.S. 25 Years on 1924–1949; Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, N. (Ed.) The Saora; Tribal and Harijan Research-cum-Training Institute: Orissa, India, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, M. Religious beliefs and practices: A case study of Saoras of Gajapati district. In Tribal Culture in Transition; Trilochan, M., Pattanayak, D., Bimalendu, M., Eds.; Utkal University of Culture: Bhubaneswar, India, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar, B.C. The Aborigines of the Highlands of Central India; University of Calcutta: Calcutta, India, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Elwin, V. The Religion of an Indian Tribe; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission, July 1914–1915; Cuttack: Orissa Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1916.

- Manshardt, C. Christianity in a Changing India: An Introduction to the Study of Missions; YMCA Publishing House: Calcutta, India, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Sumita, S. Understanding Health and Illness among tribal communities in Orissa. Indian Anthropol. 2011, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, R. Christian missionaries and their impact on socio-cultural development- undivided koraput district a study. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhotray, D.P. Health status of primitive tribes of Orissa. ICMR Bull. 2003, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Paik, P.C. Report of Canadian Baptist Missionary India, Box-2, 88–106; Canadian Baptist Mission Archives: Hamilton, UK, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Shyamala, G. Father may Be an Elephant and Mother Only a Small Basket, but …; Suneetha, A.; Bhrugabanda, U., Translators; Navayana Publishing Pvt Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, G.N.; Moharana, A.K. The santal therapy vis-a-vis animal based medicines. Adivasi 2006, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Opie, I.; Tatem, M. (Eds.) A Dictionary of Superstitions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H. Scenes and Legends of the north of Scotland: Or the Traditional History of Cromarty; A&C Black: Edinburgh, UK, 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, O.E. Rising Tides in India; The Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Orchard, R.M.L. Canadian Baptists at Work in India; Missionary Education Department of the Foreign Mission Board: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Carder, W.G. Christian Medical Service in Serango; Canadian Baptist Mission Archives: Hamilton, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Orchard, R.M.L. The Enterprise: The Jubilee Story of the Canadian Baptist Mission in India 1874 to 1924; The Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- District Statistical Handbook Ganjam; Orissa Government Press: Orissa, India, 1961.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board, India, Bethel Hospital, Vuyyuru, 1938–1939; Canadian Baptist Mission Archives: New Delhi, India, 1940.

- Leupolt, C.B. Recollections of an Indian Missionary; Church Missionary House: London, UK, 1863. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.N. Social perceptions of diseases in early India. J. Asiat. Soc. 2021, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission, 1921–1922; Canadian Baptist Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1923.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission, 1930–1931; Canadian Baptist Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1932.

- White, P. Jungle Doctor on Safari; Paternoster Press: London, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- White, P. Jungle Doctor; Paternoster Press: London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission, 1923–1924; Canadian Baptist Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1925.

- Allaby, E. Research Notes: Among the Telugus, 1930–1931; Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission; Canadian Baptist Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, O.E. Moving with the Times: The Story of Baptist Outreach from Canada into Asia, South America and Africa, during One Hundred Years, 1874–1974, since the Canadian Baptist Mission Was Founded in India; The Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, S.K. The Impact of Protestant Christianity on the lives of Panos and Saoras in Ganjam District, Orissa, from 1902–1947. Master’s Thesis, Serampore College, West Bengal, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1916–1917; Canadian Baptist Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1917.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission, 1945; Canadian Baptist Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1946.

- Katapalli, D. Transformations of Savara Tribe of Srikakulam District of Andhra Pradesh. In Christ among the Tribals; Hrangkhuma, F., Thomas, J., Eds.; SAIACS Press: Kothanur, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission, 1941; Canadian Baptist Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1942.

- Basu, R.T. Christianization and the Adivasi World of Ganjam: Canadian Baptists in the Oriya-Telugu Country, c. 1870–1970. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Calcutta, West Bengal, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Satya, R.M.; Hillmer, M.; Ban, J. (Eds.) Senior Seminar: Teaching the Gospel in the Hindu and Christian Village of Rayagoda, Ganjam District in the State of Orissa: The Place and Preparation of Sunday School Teachers’ 1950; Canadian Baptist Mission Archives: New Delhi, India, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Extracts from the Indian Report of the Orissa Baptist Mission for 1857–1858. In The Calcutta Christian Observer: Old Series to New Series XXVII–XXIX; Baptist Mission Press: New Delhi, India, 1858; pp. 7–8.

- Acc. No. 2614G, File 1 (25 October 1930); Judicial Department, Orissa State Archives (hereafter OSA): Bhubaneswar, Orissa, India.

- Acc. No. 2512G, File 2 (25 October 1930); Judicial Department: OSA: Bhubaneswar, Orissa, India.

- Acc. No. 2473G, File 2 (25 October 1930); Judicial Department: OSA: Bhubaneswar, Orissa, India.

- Hardgrave, R.L. The Nadars of Tamilnad: The Political Culture of a Community in Change; University of California Press: Berkeley, LA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- National Archives of India. Proceedings Nos. 81–82, July 1925; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 1926.

- W. Gordon Carder’s Report on Serango: The Saoras, A General Work, 1941; McMaster University: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 1942.

- Proceedings Nos. 63–65, July 1943; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 1944.

- Chatterji, A.P. Violent Gods: Hindu Nationalism in India’s Present- Narratives from Orissa; Three Essays Collective: New Delhi, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pachuau, L. In search of a context for a contextual theology: The socio-political realities of “Tribal” Christians in Northeast India. In Search of Identity and Tribal Theology: A Tribute to Dr. Renthy Keitzar; Wati Longchar, A., Ed.; Eastern Theological College, Tribal Study Centre: Assam, India, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Basu Roy, T. Spirituality and Conflict in Healthcare: The History of the Canadian Baptists and Medical Mission in Orissa, 1900–1970. Histories 2021, 1, 69-84. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories1020011

Basu Roy T. Spirituality and Conflict in Healthcare: The History of the Canadian Baptists and Medical Mission in Orissa, 1900–1970. Histories. 2021; 1(2):69-84. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories1020011

Chicago/Turabian StyleBasu Roy, Tiasa. 2021. "Spirituality and Conflict in Healthcare: The History of the Canadian Baptists and Medical Mission in Orissa, 1900–1970" Histories 1, no. 2: 69-84. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories1020011

APA StyleBasu Roy, T. (2021). Spirituality and Conflict in Healthcare: The History of the Canadian Baptists and Medical Mission in Orissa, 1900–1970. Histories, 1(2), 69-84. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories1020011