Primary Hyperparathyroidism Can Generate Recurrent Pancreatitis and Secondary Diabetes Mellitus—A Case Report

Highlights

- In cases of recurrent renal lithiasis or pancreatitis, screening for hyperparathyroidism is recommended.

- Metabolic evaluation is required in patients with recurrent pancreatitis because of their high risk of developing diabetes.

Abstract

Introduction

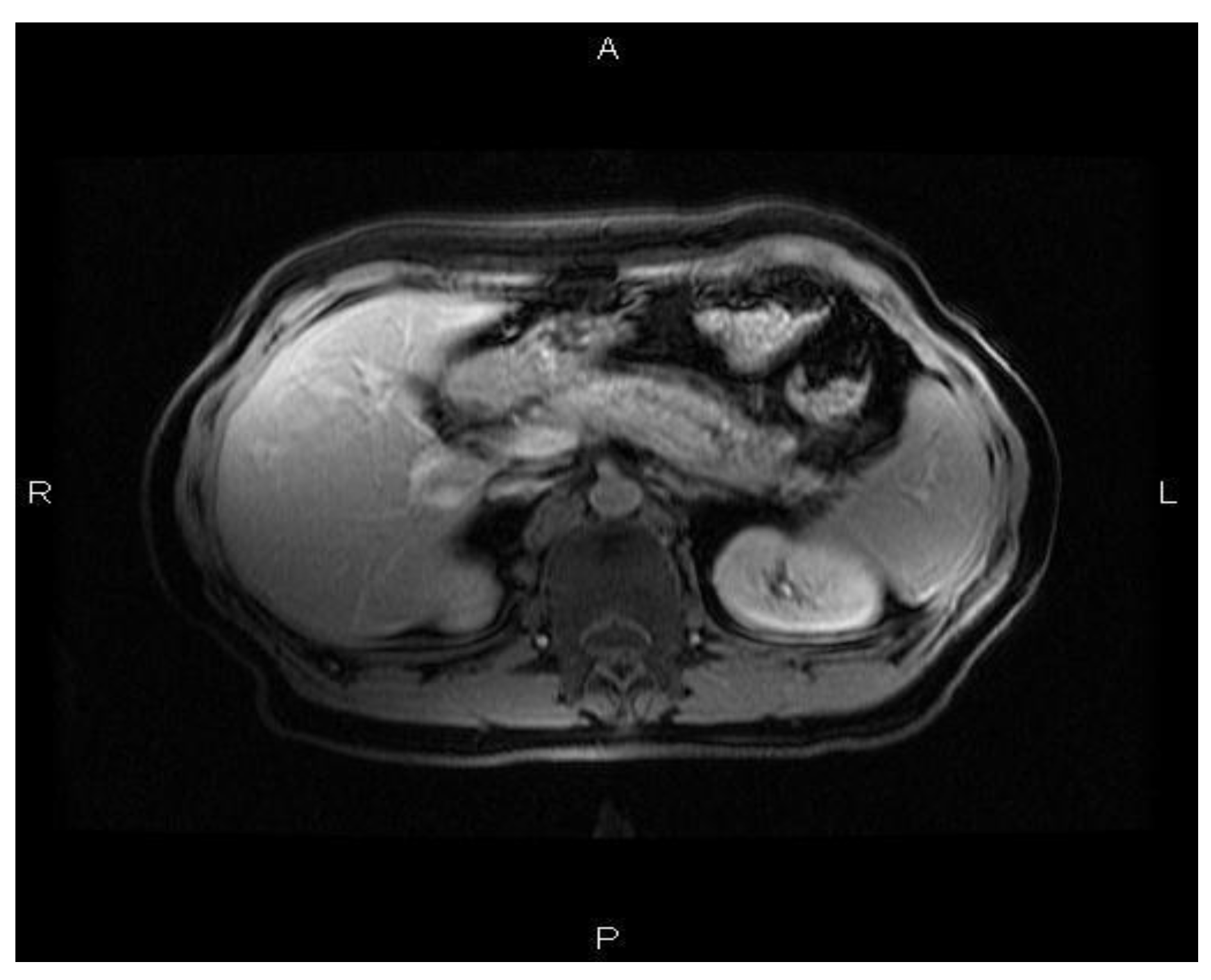

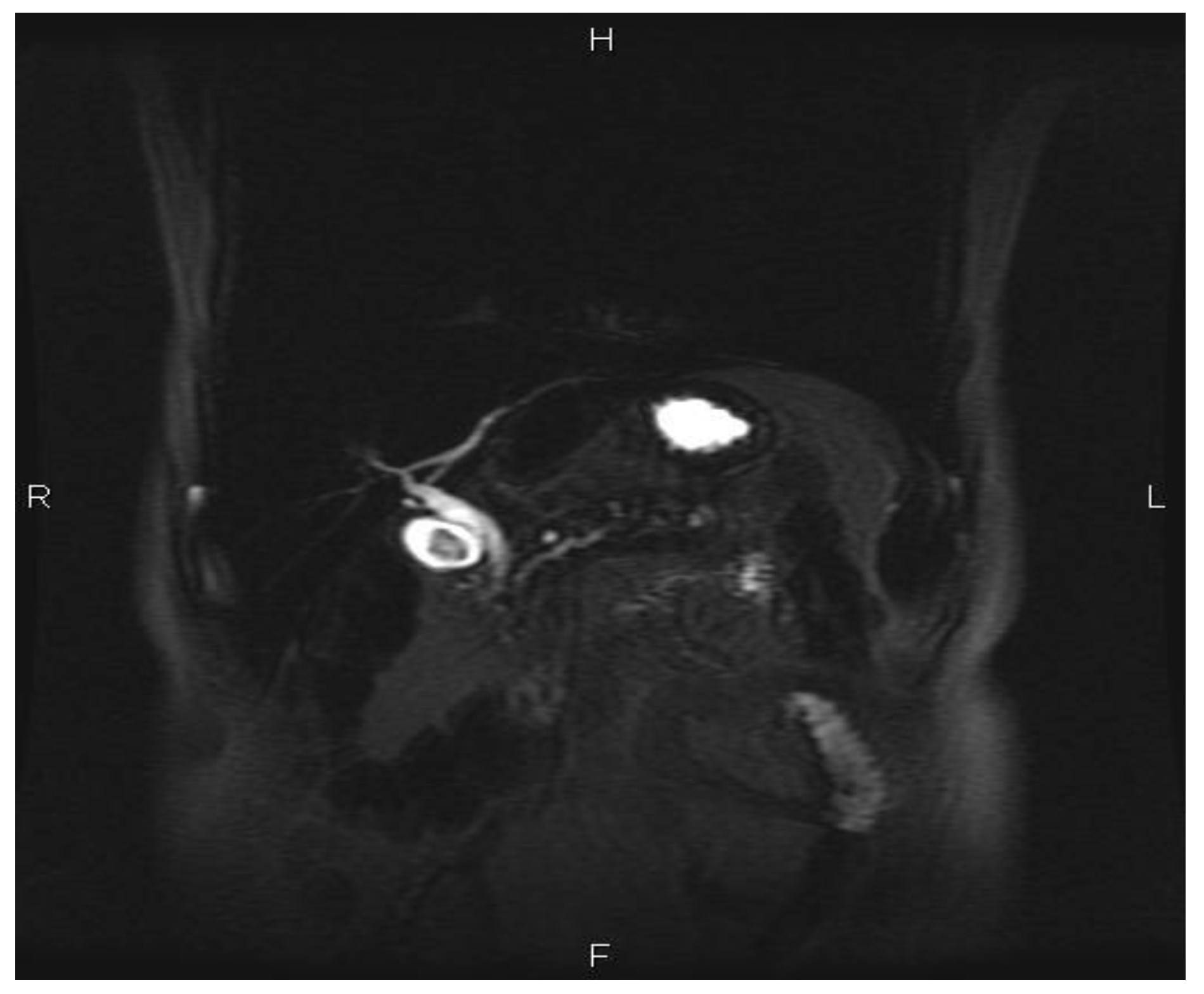

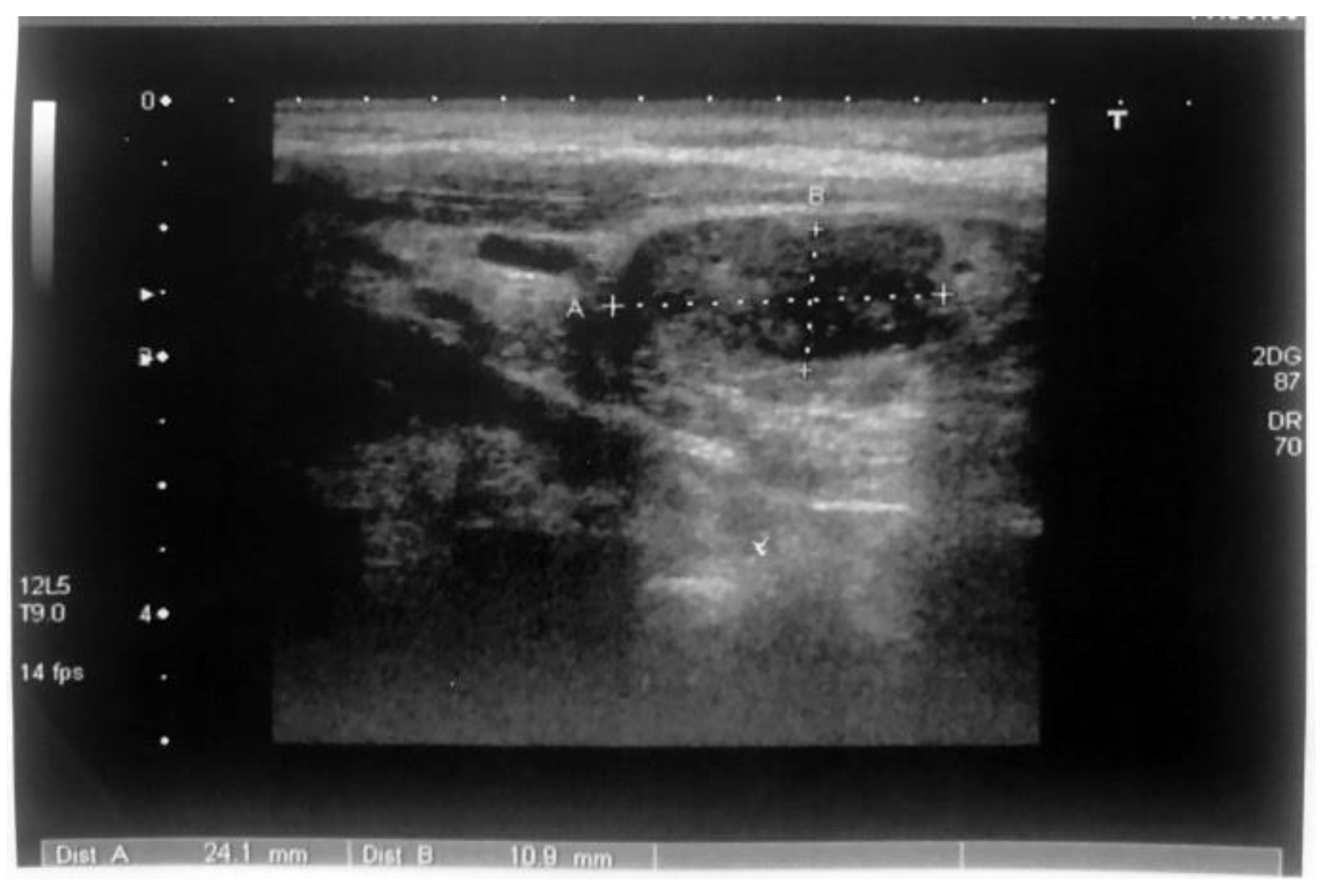

Case Reports

Discussions

Conclusions

Conflict of interest disclosure

Compliance with ethical standards

References

- Madkhali, T.; Alhefdhi, A.; Chen, H.; Elfenbein, D. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2016, 32, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, G.; Di Somma, C.; Rubino, M.; Faggiano, A.; Vuolo, L.; Guerra, E.; Contaldi, P.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. The roles of parathyroid hormone in bone remodeling: Prospects for novel therapeutics. Endocrinol Invest. 2011, 34, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo, L.S. Regulation of calcium and phosphate homeostasis. Adv Physiol Edu. 1998, 20, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilezikian, J.P.; Cusano, N.E.; Khan, A.A.; Liu, L.M.; Marcocci, C.; Bandeira, F. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016, 2, 16033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg, S.J.; Walker, M.D.; Bilezikian, J.P. Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Densitom. 2013, 16, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, O.; Culver, P.J.; Mixter, C.G., Jr.; Nardi, G.L. Pancreatitis, a diagnostic clue to hyperparathyroidism. Ann Surg. 1957, 145, 857–863. [Google Scholar]

- Sitges-Serra, A.; Alonso, M.; de Lecea, C.; Gores, P.F.; Sutherland, D.E. Pancreatitis and hyperparathyroidism. Br J Surg. 1988, 75, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, T.K.; Vege, S.S.; Abu-Lebdeh, H.S.; Ryu, E.; Nadeem, S.; Wermers, R.A. Acute Pancreatitis in Primary Hyperparathyroidism: A Population-Based Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009, 94, 2115–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Andersen, D.K. Pancreatogenic diabetes: Special considerations for management. Pancreatology. 2011, 11, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Makuc, J. Management of pancreatogenic diabetes: Challenges and solutions. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016, 9, 311–315. [Google Scholar]

- Ewald, N.; Bretzel, R.G. Diabetes mellitus secondary to pancreatic diseases (Type 3c)—Are we neglecting an important disease? Eur J Intern Med. 2013, 24, 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Mallette, L.E.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Heath, D.A.; Aurbach, G.D. Primary hyperparathyroidism: Clinical and biochemical features. Medicine (Baltimore). 1974, 53, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mollerup, C.L.; Vestergaard, P.; Frøkjær, V.G.; Mosekilde, L.; Christiansen, P.; Blichert-Toft, M. Risk of renal stone events in primary hyperparathyroidism before and after parathyroid surgery: Controlled retrospective follow up study. BMJ. 2002, 325, 785–786. [Google Scholar]

- Starup-Linde, J.; Waldhauer, E.; Rolighed, L.; Mosekilde, L.; Vestergaard, P. Renal stones and calcifications in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: Associations with biochemical variables. Ear J Endocrinol. 2012, 166, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Evan, A.P. Physiopathology and etiology of stone formation in the kidney and the urinary tract. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010, 25, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Letavernier, E.; Daudon, M. Vitamin D, Hypercalciuria and Kidney Stones. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 366. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett, S.D.; Wani, S.; Gardner, T.B.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Barkun, A.N. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline of Initial Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018, 154, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Sakorafas, G.H.; Tsiotou, A.G. Etiology and pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis: Current concepts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000, 30, 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, F.B.; Cook, R.T. Acute fatal hyperparathyroidism. Lancet. 1940, 2, 650. [Google Scholar]

- Mixter, C.G.; Keynes, W.M.; Cope, O. Further experience with pancreatitis as a diagnostic clue to hyperparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 1962, 266, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Sitges-Serra, A.; Alonso, M.; de Lecea, C.; Gores, P.F.; Sutherland, D.E. Pancreatitis and hyperparathyroidism. Br J Surg. 1988, 75, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.X.; Giefer, M.; Patel, M.; Orbi AIHusain, S.Z. The Association of primary Hyperparathyroidism with Pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012, 46, 656–661. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.; Criddle, D.; Raraty, M.G.; Tepikin, A.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Petersen, O.H. Signal transduction, calcium and acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2003, 3, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, S.Z.; Grant, W.M.; Gorelick, F.S.; Nathanson, M.H.; Shah, A.U. Caerulein-induced intracellular pancreatic zymogen activation is dependent on calcineurin. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007, 292, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, B.; Gaiser, S.; Chen, X.; Ernst, S.A.; Logsdon, C.D. Intracellular trypsin induces pancreatic acinar cell death but not NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284, 17488–17498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dawra, R.; Sah, R.P.; Dudeja, V.; Rishi, L.; Saluja, A.K. Intra- acinar trypsinogen activation is required for early pancreatic injury but not for inflammation during acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2011, 141, 2210–2217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stanescu, A.M.A.; Grajdeanu, I.V.; Iancu, M.A.; et al. Correlation of Oral Vitamin D Administration with the Severity of Psoriasis and the Presence of Metabolic Syndrome. Revista de Chimie 2018, 69, 1668–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ji, B.; Han, B.; Ernst, S.A.; Simeone, D.; Logsdon, D.C. NF-kappaB activation in pancreas induces pancreatic and systemic inflammatory response. Gastroenterology. 2002, 122, 448–457. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, B.; Wagner, M.; Aleksic, T.; von Wichert, G.; Weber, C.K.; Adler, G.; Wirth, T. Constitutive IKK2 activation in acinar cells is sufficient to induce pancreatitis in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007, 117, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, O.; Robles-Diaz, G.; Adrich, Z.; Sahel, J.; Salrles, H. Protein content of precipitates present in pancreatic juice of alcoholic subjects and patients with chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1983, 84, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Dănciulescu Miulescu, R.; Guja, L.; Ochiana, L.C.; Ungurianu, A.; Șeremet, O.C.; Ștefănescu, E. Serum markers of bone fragility in type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Mind Med Sci. 2019, 6, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.A.; Bellin, M.D.; Anderson, D.A.; Bradley, D.; Cruz-Monserrate, Z.; Forsmark, C.E.; Goodarzi, M.O.; Habtezion, A.; Korc, M.; Kudva, Y.C.; Pandol, S.J.; Yadav, D.; Chari, S.T. Type 3c (pancreatogenic) diabetes mellitus secondary to chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016, 1, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Xin, L.; Wang, D.; Liao, Z.; Lin, J.H.; Li, B.R.; Du, T.T.; Te, B.; Zou, W.B.; Chen, H.; Ji, J.T.; Zhrng, Z.H.; Hu, L.H.; Li, Z.S. Risk Factors for Diabetes Mellitus in Chronic Pancreatitis. A Cohort of 2011 Patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016, 95, e3251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malka, D.; Hammel, P.; Sauvanet, A.; Rufat, P.; O’Toole, D.; Bardet, P.; Belghiti, J.; Bemades, P.; Ruszniewski, P.; Lévy, P. Risk factors for diabetes mellitus in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2000, 119, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Rickels, M.R.; Bellin, M.; Toledo, F.G.S.; Robertson, R.P.; Andersen, D.K.; Chari, S.T.; Brad, R.; Frulloni, L.; Anderson, M.A.; Whitcomb, D.C. Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus in Chronic Pancreatitis: Recommendations from Pancreas Fest 2012. Pancreatology 2013, 13, 336–342. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. 2019 Nicoleta Mîndrescu, Georgeta Văcaru, Emil Ștefănescu, Loreta Guja, Rucsandra Elena Dănciulescu Miulescu

Share and Cite

Mîndrescu, N.; Văcaru, G.; Ștefănescu, E.; Guja, L.; Dănciulescu Miulescu, R.E. Primary Hyperparathyroidism Can Generate Recurrent Pancreatitis and Secondary Diabetes Mellitus—A Case Report. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2019, 6, 361-366. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.62.P361366

Mîndrescu N, Văcaru G, Ștefănescu E, Guja L, Dănciulescu Miulescu RE. Primary Hyperparathyroidism Can Generate Recurrent Pancreatitis and Secondary Diabetes Mellitus—A Case Report. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2019; 6(2):361-366. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.62.P361366

Chicago/Turabian StyleMîndrescu, Nicoleta, Georgeta Văcaru, Emil Ștefănescu, Loreta Guja, and Rucsandra Elena Dănciulescu Miulescu. 2019. "Primary Hyperparathyroidism Can Generate Recurrent Pancreatitis and Secondary Diabetes Mellitus—A Case Report" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 6, no. 2: 361-366. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.62.P361366

APA StyleMîndrescu, N., Văcaru, G., Ștefănescu, E., Guja, L., & Dănciulescu Miulescu, R. E. (2019). Primary Hyperparathyroidism Can Generate Recurrent Pancreatitis and Secondary Diabetes Mellitus—A Case Report. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 6(2), 361-366. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.62.P361366