Introduction

Necrotizing fasciitis represents an infection of bacterial origin, with low frequency, but capable of skin and soft tissue destruction, affecting even fascia that cover muscles and subcutaneous fat. Because of its extremely fast evolution, the main agent has been called “flesh eating” bacteria. Streptococcus pyogenes cause the occurrence and development of this rare but severe disease with the involvement of the subcutaneous fat tissue and thrombosis of the microvasculature [

1].

In 30% of necrotizing fasciitis, fatalities are registered, even if the patients are completely healthy prior to the occurrence of the infection. Classification of the soft tissue necrotizing fasciitis takes into consideration the presence or absence of clostridium bacteria. However, the onset of the purulent collection is due to the polymicrobial association [

2]. The neck region is one of the anatomic regions with the highest number of anaerobic bacteria [

3]. Some studies have noted differences between skin and throat strains in their epidemiology and genetic makeup, thus resulting in different levels of virulence [

4].

Individuals that are susceptible for developing such an infection are those:

having a weakened immune system or not having the necessary antibodies to fight infection.

affected by chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer, liver or kidney diseases.

with post-surgical wounds that are healing, such as episiotomy.

recently affected by smallpox virus or other viral infections which produce cutaneous eruptions.

using steroid medication causing an impairment of the immune system in fighting infections

However, the anatomical configuration represented by the fibrous attachments between subcutaneous tissues and fascia helps limit the spread of infection [

5].

The authors present in this paper the case of a 60 year old woman with multiple morbidities, diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis. Due to associated morbidities, the patient had a poor and rapid evolution towards death, this occurring on the 11th day of hospitalization.

Case Report

The 60 years old patient had a known personal pathological history: type II diabetes mellitus insulin dependent, chronic bronchitis with asthma, chronic heart disease, and peripheral polyneuropathy. She was admitted to our Otorhinolaryngology/ ENT Department, having been transferred from a city hospital 2 days after admission. She was suffering from: dysphagia, odynophagia, extended feverish syndrome, extended necrosis on the left lateral cervical region, and poor biological status.

ENT clinical examination revealed facial swelling extended to the left anterior and latero-cervical region and edema and congestion of the teguments with some cyanotic regions. The area was painful when touched, infiltrated and crumble, gaseous crepitation were present at palpation. Mouth and pharynx endoscopy was difficult to perform because of the trismus and the odontogenic infection located on the left side. The tongue seemed mobile and the sublingual region was painful with accompanying edema. Indirect laryngoscopy revealed edema of left hemilarynx with salivary stasis, a necrotic area in left piriform sinus which communicated with the left lateral cervical necrosis, with a fistula communicating with the exterior under formation.

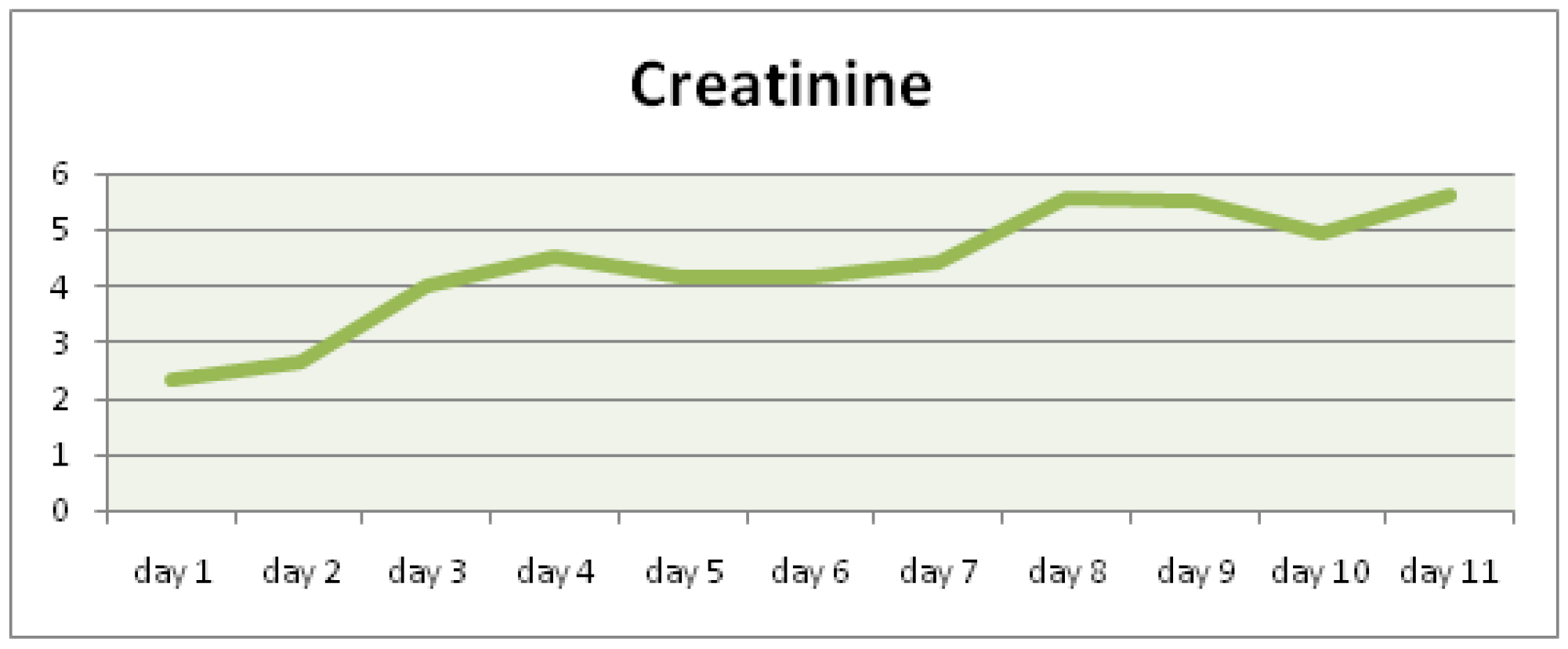

At admission the blood test revealed leukocytosis, along with kidney failure (creatinine: 2,31 mg/dl, urea: 121,98 mg/dl, creatinine clearance: 22 ml/min/1,73m2 according to MDRD), as well as oscillatory modification of sugar levels (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Emergency surgical treatment was performed, multiple latero-cervical incisions being made on the left side and all necrotic areas were removed. Hydrogen peroxide and iodine solution were used to cleanse the area.

At admission the patient received broad spectrum antibiotic therapy consisting of Cefort 2x2g/day, Clindamycin 3x2g/day, and Metronidazole 2x1fl/day, rehydration, antipyretics, and treatment for diabetes mellitus, bronchitis, and heart disease, as a primary empiric therapy. Before antibiotherapy, microbial cultures were taken and an antibiogram was performed. The microbiological examination was negative. On the 3rd day the cultures from the latero-cervical secretions became positive for Seratia.

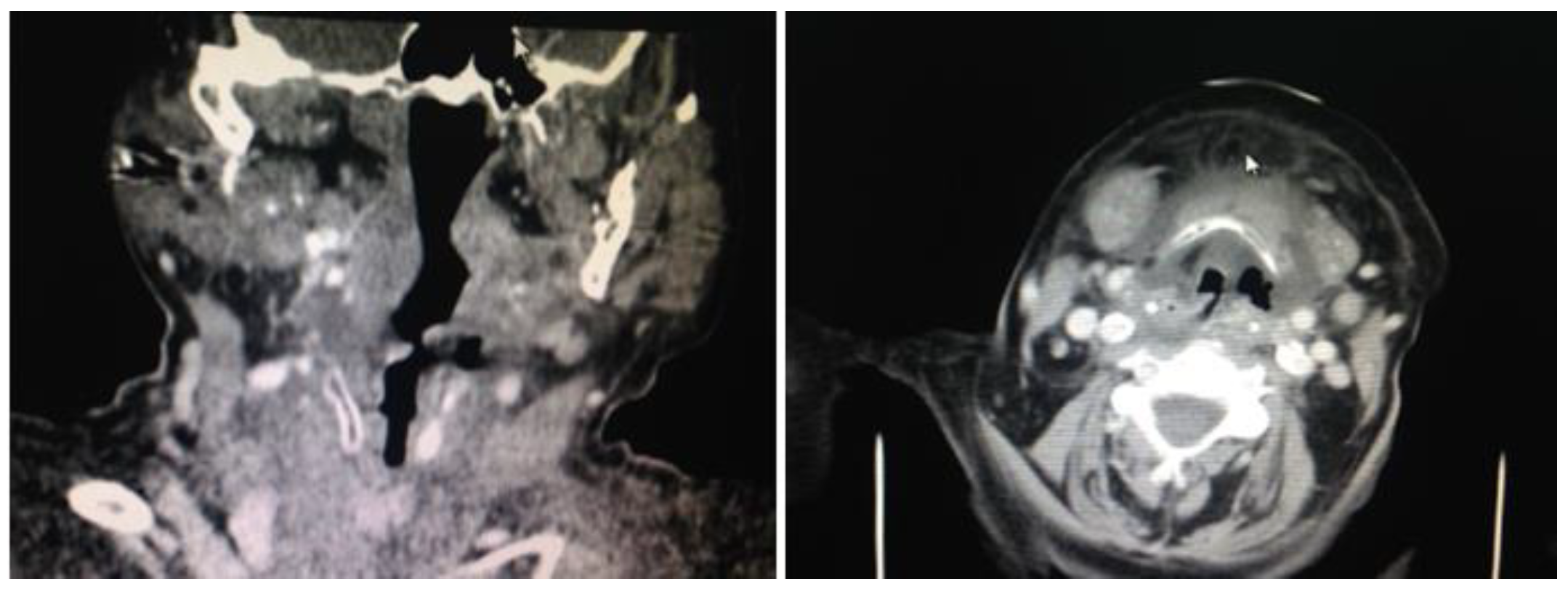

Paraclinical examination using imaging studies of the cervical and thorax regions revealed consistent collection surrounding the pharynx and the prevertebral space. The pharynx cavity had a reduced asymmetrical lumen. The subcutaneous tissue was infiltrated with extensive edema. Multiple lymph nodes were visible on the left submandibular space with diameters up to 15 mm. Left submandibular gland was infiltrated. The native and contrast thorax CT revealed normally expanded lungs, no spontaneous visible focal lesions or post intravenous contrast, no pleural collections or effusions, and no mediastinal adenopathy of pathological dimensions. The CT diagnosis was possible and revealed parapharynx and submental phlegmon (

Figure 4).

During hospitalization, the patient developed acute kidney failure, and therefore nephrology emergency examination was required. Emergency dialysis in the ER was decided 3 days after admission in the ENT Department.

On the 2nd day of hospitalization the patient developed suppurated otitis, with the secretion being harvested for culture. Microbiological examination by seriated cultures revealed the presence of Enterococcus faecium, sensible to vancomicyn and linezolid. On the 3rd day the secretions harvested the previous days from the necrotic tissue became positive for Seratia, sensible to colistin and amikacin.

Based on the microbiological results, antibiotic treatment was modified with specific antibiotic agents, colistin and vancomicyn being used along with metronidazol. Antipyretics and treatments for diabetes, kidney failure, and bronchitis were administered.

On the 4th day the patient’s biological status improved and the patient’s clinical profile was stable. However, on the 5th day the patient’s biological and chemical status worsened, with high blood glucose levels, high creatinine and urea levels, and ionic imbalance. On the 6th day the patient was transferred to the nephrology department for dialysis. The patient’s respiratory, heart, and kidney functions deteriorated continuously and the patient was transferred to the intensive therapy unit with MSOF (multisystem organ failure). The patient underwent two more dialysis sessions in the intensive therapy unit but with no favorable result. Death occurred on the 11th day of hospitalization due to kidney failure, septicemia, and MSOF, complications mostly due to the unbalanced and non-responsive diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

Due to the anatomical complexity of the cervical area, deep space infections frequently represent a challenge for the ENT specialist. Cervical fasciitis is a serious complication with 20-30% mortality, which appears in elderly and immunology-depressed persons. It evolves extremely rapidly as a cervical cellulite, and death may occur in 24 to 96 hours [

6,

7]. The skin appears like an orange peel as a result of lymphatic drainage blockage and the presence of air trapped beneath the skin, causing crepitations. Antibiotic therapy needs to be targeted by using specific agents following an antibiogram, this being considered a priority of the therapy management. At admission the patient received broad spectrum antibiotic therapy. Pathogenesis and clinical manifestations are important to differentiate between different pathogens involved in the development of the localized infection [

8].

The removal of dead necrotic tissue, consisting of friable gray tissue, and brownish, watery, odorous secretions, is the most important part of the therapy management. If the site of infection or necrotic tissue is significant, the local and general status of the organism is impaired and the prognosis worsens. The wound is left open so that seriated debridement and washing can be performed daily. After healing, plastic surgery may be needed. In our case the patient had a rapid and violent deterioration, even though surgery was performed and broad spectrum antibiotics were administered immediately. Specific therapy was later administered according to the antibiogram [

9]. In our case, it appeared that the complications of diabetes led to patient immunology suppression and kidney failure, septicemia, and MSOF.

Even though surgical and medical treatment were urgently performed by a multidisciplinary medical team representing ENT- Diabetology- Nephrology- Internal Medicine-Radiology, the evolution was unfavorable, due primarily to unbalanced diabetes and late complications.