Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy, Physical and Mental Consequences: A 6-Year Study

Abstract

:Introduction

Materials and methods

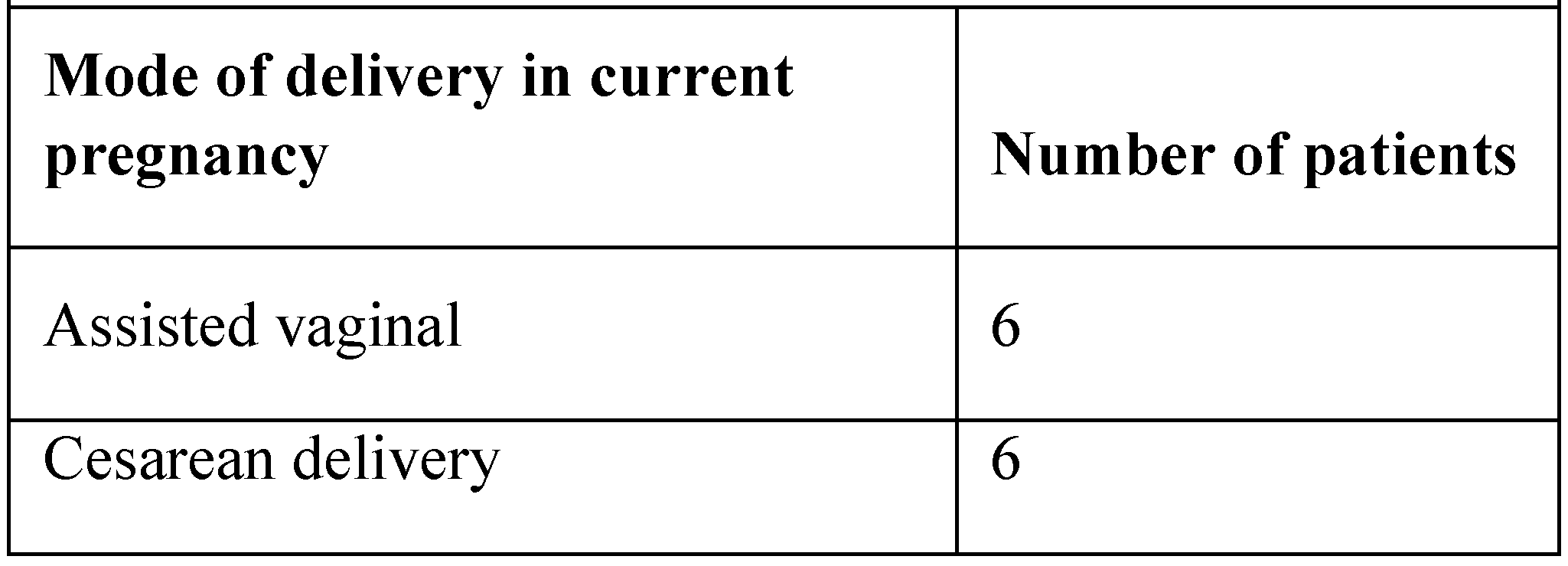

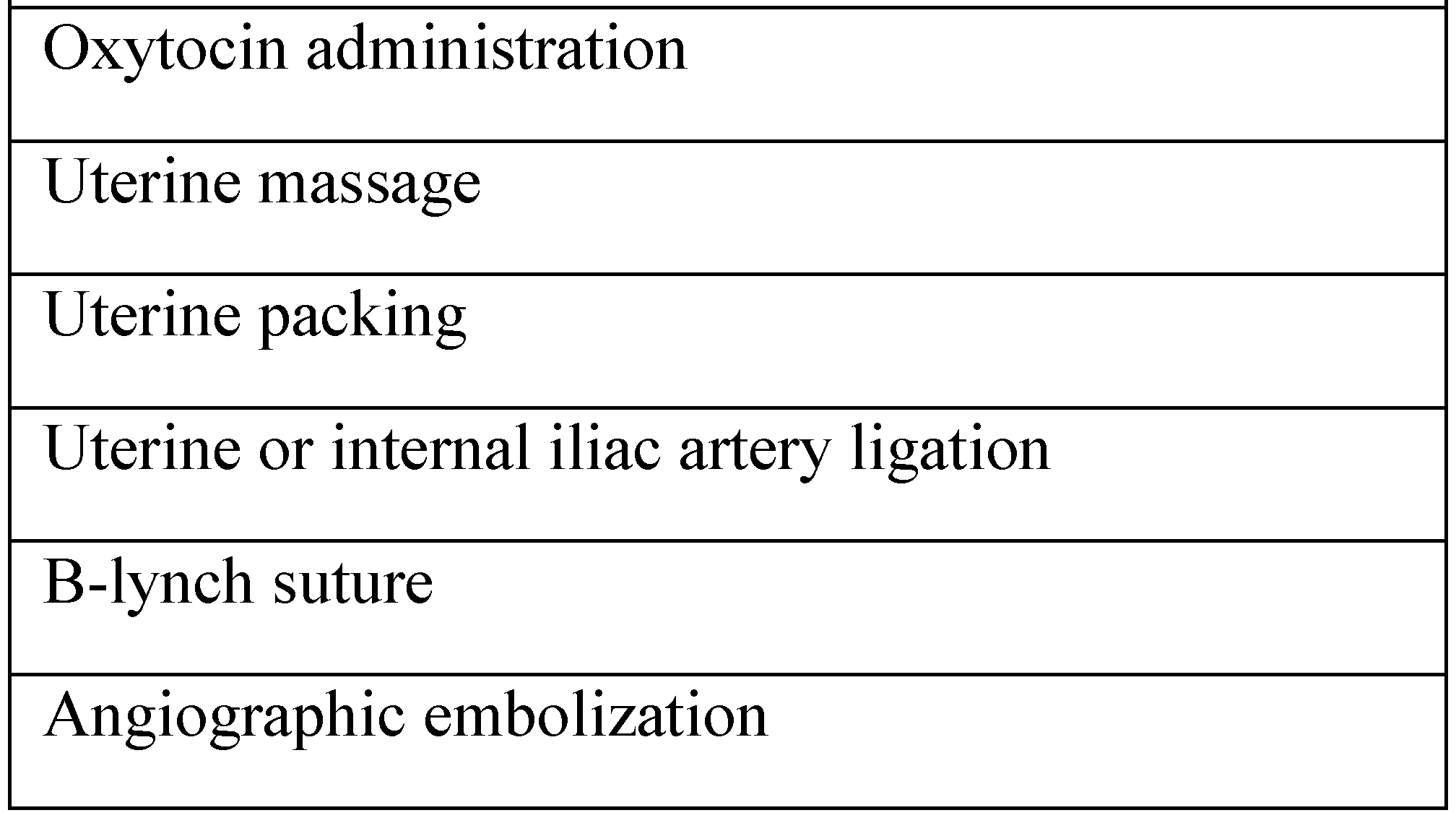

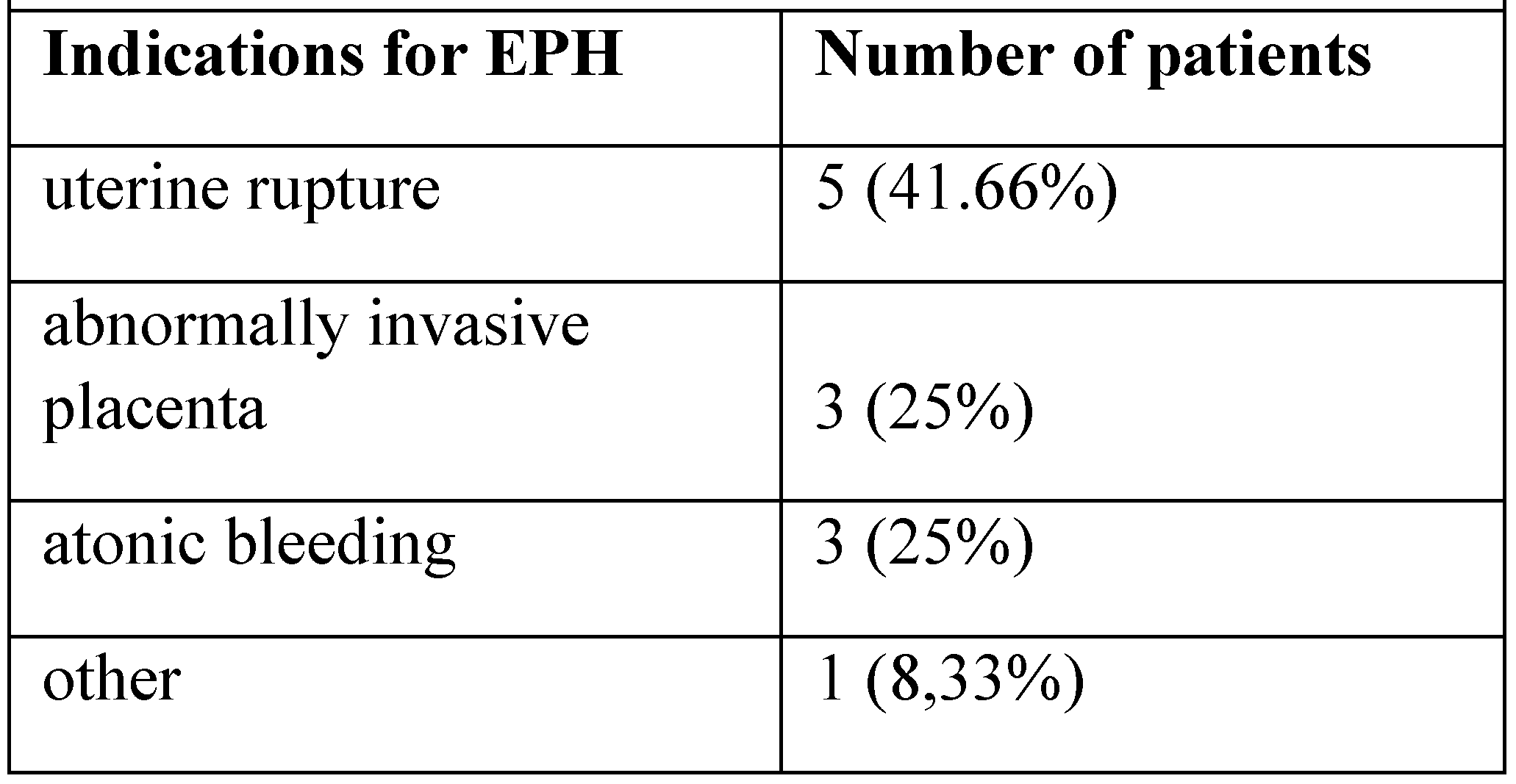

Results

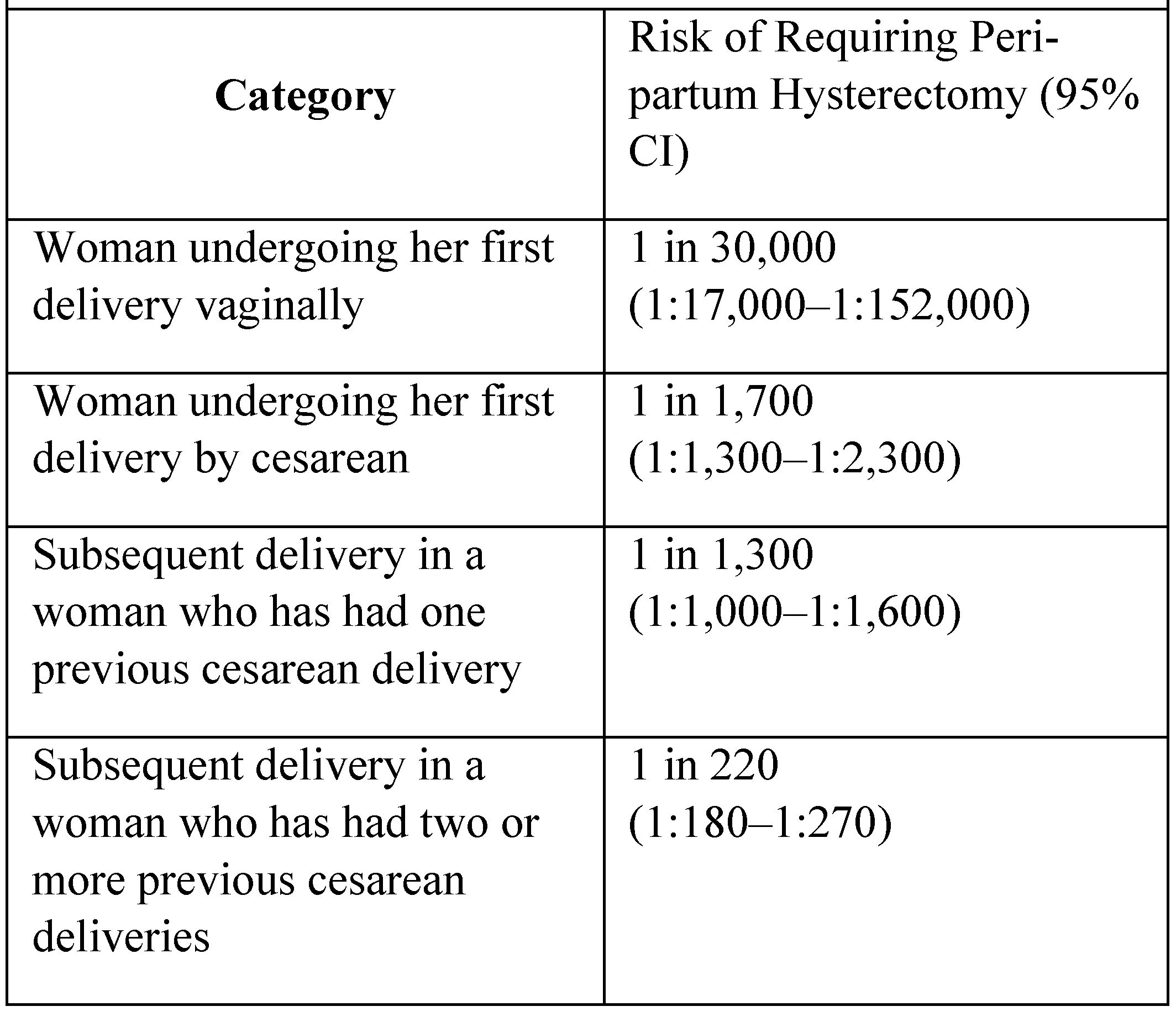

Discussions

Conclusions

References

- Knight, M.; Kurinczuk, J.J.; Spark, P.; Brocklehurst, P. Cesarean Delivery and Peripartum Hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 111, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanterm, T.; Chittacharoen, A.; Ayudhya, N.I.N. Risk factors of emergency peripartum hysterectomy. Thai Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2015, 23, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson, M.; Tapper, A.M.; Colmorn, A.M.; Lindqvist, P.G.; Klungsøyr, K.; Krebs, L.; Børdahl, P.E.; Gottvall, K.E.; Källén, K.; Bjarnadóttir, R.I.; Langhoff-Roos, J.; Gissle, M. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: results from the prospective nordic obstetric surveillance study (noss). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015, 94, 745–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macharey, G.; Ulander, V.M.; Kostev, K.; Väisänen- Tommiska, M.; Ziller, V. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy and risk factors by mode of delivery and obstetric history: a 10-year review from Helsinki University Central Hospital. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 2015, 43, 721–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalinkaya, A.Q.; Güzel, A.I.; Kangal, K. Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy: 16-year Experience of a Medical Hospital. J Chin Med Assoc 2010, 73, 360–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.Y. Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy, a 10-year review in a tertiary obstetric hospital. The New Zeeland Medical Journal 2011, 124, 34–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, S.; Guzin, K.; Eroğlu, M.; Kayabasoglu, F.; Yaşartekin, M.S. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: our 12-year experience. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2014, 289, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibber, R.; Al-Hijji Fouda, M.; Al-Saleh, E.; Al- Adwani, A.R.; Mohammed, A.T. A 26-Year Review of Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy in a Tertiary Teaching Hospital in Kuwait – Years 1983–2011. Med Princ Pract 2012, 21, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawad, A.; Islam, A.; Naz, H.; Nelofar, T.; Abbasi, U.N. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy- a life saving procedure. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2015, 27, 143–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zelop, C.M.; Harlow, B.L.; Frigoletto Jr, F.D.; Safon, L.E.; Saltzman, D.H. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy. American journal of Ostetrics and Gynecology 1993, 168, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balalau, C.; Popa, F.; Negrei, C.; Andreianu, P. Therapeutic attitude in perforated stress ulcer. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2011, 115, 1119–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors. 2016 Denisa-Oana Bălălău, Romina Marina Sima, Nicolae Bacalbașa, Liana Pleș, Anca Daniela Stănescu. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bălălău, D.-O.; Sima, R.M.; Bacalbașa, N.; Pleș, L.; Stănescu, A.D. Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy, Physical and Mental Consequences: A 6-Year Study. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2016, 3, 65-70. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1035

Bălălău D-O, Sima RM, Bacalbașa N, Pleș L, Stănescu AD. Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy, Physical and Mental Consequences: A 6-Year Study. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2016; 3(1):65-70. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1035

Chicago/Turabian StyleBălălău, Denisa-Oana, Romina Marina Sima, Nicolae Bacalbașa, Liana Pleș, and Anca Daniela Stănescu. 2016. "Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy, Physical and Mental Consequences: A 6-Year Study" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 3, no. 1: 65-70. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1035

APA StyleBălălău, D.-O., Sima, R. M., Bacalbașa, N., Pleș, L., & Stănescu, A. D. (2016). Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy, Physical and Mental Consequences: A 6-Year Study. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 3(1), 65-70. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1035