1. Introduction

Nowadays, computer vision algorithms have been employed to develop crack contour models for assessing surface quality in the manufacturing sector [

1]. This mathematical modeling is a crucial process for determining crack regions on the surface being examined [

2]. Thus, computer vision techniques have been employed for characterizing crack contours to quantify crack areas on a surface being inspected [

3]. Hence, the crack areas are determined from the crack contours to assess the surface quality. This enables an effective surface crack inspection during the manufacturing process. Typically, the characterization of crack contours has been performed using computer vision methods such as filtering, segmentation, frequency domain, and deep learning. For instance, the characterization of crack contours has been deployed through Gaussian filtering and morphological operations [

4], which identify crack regions through a contour fitting. Also, the characterization of crack contours has been carried out using homomorphic filtering that relies on a local threshold to establish the crack area [

5], which is outlined by means of morphological operations and edge detection. Similarly, the crack contour has been defined by applying a Laplacian operator with a Gaussian smoothing filter [

6], which determines the crack region by detecting high frequencies. Moreover, characterization of the crack contour has been developed via segmentation using image processing methods. In this context, the characterization of crack contours has been performed by means of segmentation using histogram equalization and binarization [

7], which determines the region in which to perform a thinning for obtaining a crack skeleton. Also, the characterization of crack contours has been realized through segmentation utilizing an ortoboundary algorithm [

8], which determines the crack area through the edge’s shortest distance and an orthogonal projection. Additionally, characterization of crack contours has been carried out using a segmentation network that relies on refined masks [

9], which perform a semantic feature extraction to obtain crack edge details. In the same way, characterization of crack contours has been performed using skeleton techniques based on image processing. For example, characterization of crack contours has been carried out using a linear crack skeleton [

10], which is fitted by a polynomial curve to determine the measurements of crack contours. Similarly, outlining of crack contours has been carried out using a linear crack skeleton with a flexible kernel of appropriate range [

11], which extracts the skeleton from a division of the crack’s boundaries. Furthermore, characterization of crack contours has been implemented employing frequency domain methods. In this field, the characterization of crack contours has been effectuated using the Fourier transform [

12], which determines discontinuities across the surfaces of the filled crack. Also, characterization of crack contours has been carried out using Fourier transform to detect planar defects [

13], where the crack shape is determined based on a growth equation. Similarly, characterization crack of contours has been performed using multi-stage Fourier transform [

14], which detects the crack surface through the secondary peaks in the Fourier transform spectrum. Recently, characterization of crack regions has been performed using deep learning methods via residual and convolutional neural networks. For instance, the modeling of crack contours has been carried out using a residual neural network [

15], which learns from an image dataset and model hyper parameters to identify crack regions. Also, the modeling of crack contours has been performed through a residual neural network trained on ImageNet featuring cracks [

16] and by computing a gradient-weighted class activation mapping. Similarly, the modeling of crack areas has been developed using a convolutional neural network focused on segmentation via crack images [

17] and utilizes a stochastic gradient for learning to classify and locate crack areas. Also, crack modeling has been implemented using a convolutional neural network that relies on feature maps [

18], where the training is effectuated with a crack dataset to identify cracks by means of feature maps.

The above-mentioned methods perform the modeling of crack contours using the distribution of pixel intensity. Nonetheless, the intensity profile does not accurately represent the crack topography. This is because the intensity distribution varies based on the surface reflectance, light source position, and viewer’s angle. These statements imply that conventional crack modeling techniques do not represent the crack profile through the real topography. This reduces accuracy in the modeling of crack contours. Additionally, deep learning methods build extensive models using a great number of images, resulting in reduced accuracy and slower performance [

19]. This occurs because thousands of images are used to train the neural network models. Consequently, complex optimization must be performed to achieve the modeling of crack contours. Moreover, model optimization is carried out through additional parameters, resulting in supplementary procedures to obtain the crack contour model. On the other hand, simpler curve models such as polylines, B-splines, and clothoids have been used to build contour models. In this case, the polylines method fails to accurately represent contour curves [

20], requiring a great number of lines to represent a contour curve. Also, the simpler B-splines do not intersect all points [

21], requiring weights to achieve an accurate contour curve. Additionally, the clothoids curve is defined by cosine and sine functions [

22], but an optimal curvature should be optimized to provide a contour curve. Furthermore, contour curves have been built using least squares to optimize Bezier functions [

23], which do not pass through all points. Moreover, classical ridge/valley detectors have been employed to detect crack areas using image processing methods [

24], which provide bi-dimensional information but low accuracy in three-dimensional coordinates. These criteria indicate that the modeling of crack contours remains a challenging endeavor. Consequently, it is essential to develop biomimetics theories for constructing crack contour models, emulating models of nature through metaheuristic algorithms and crack topography to improve crack assessment.

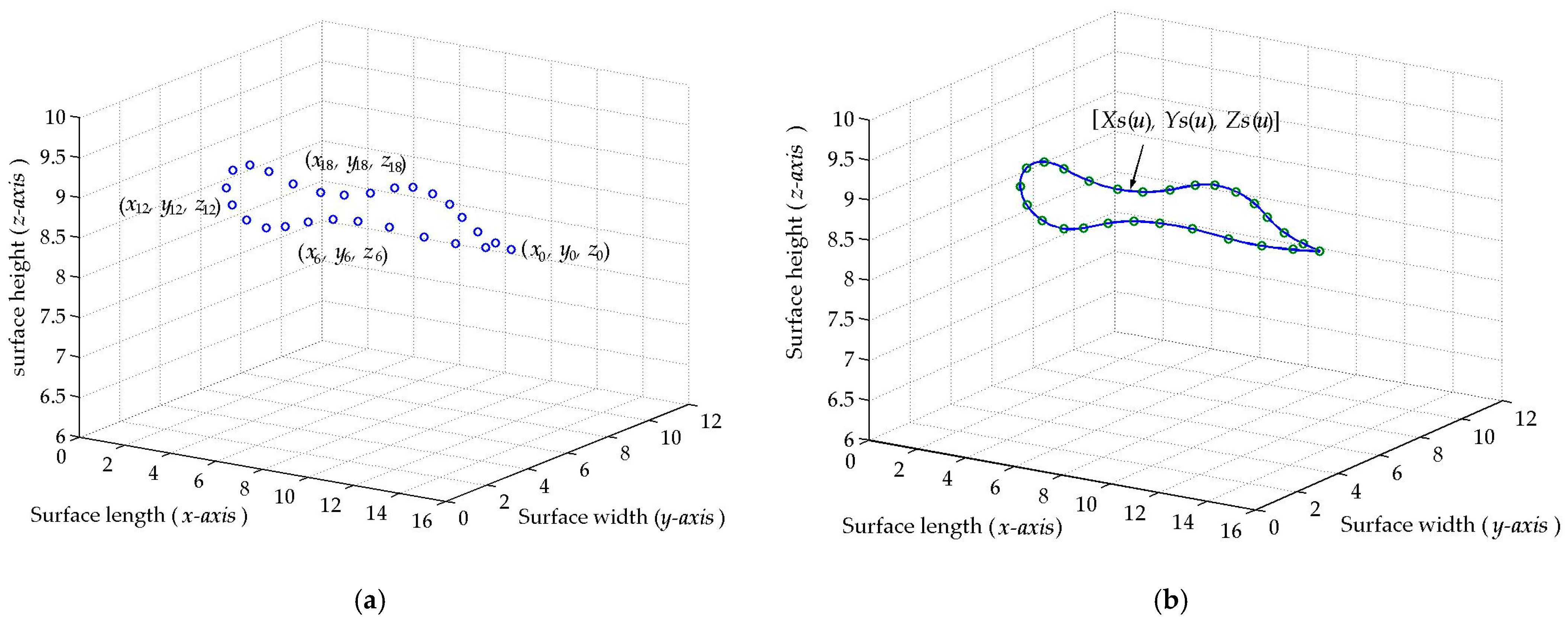

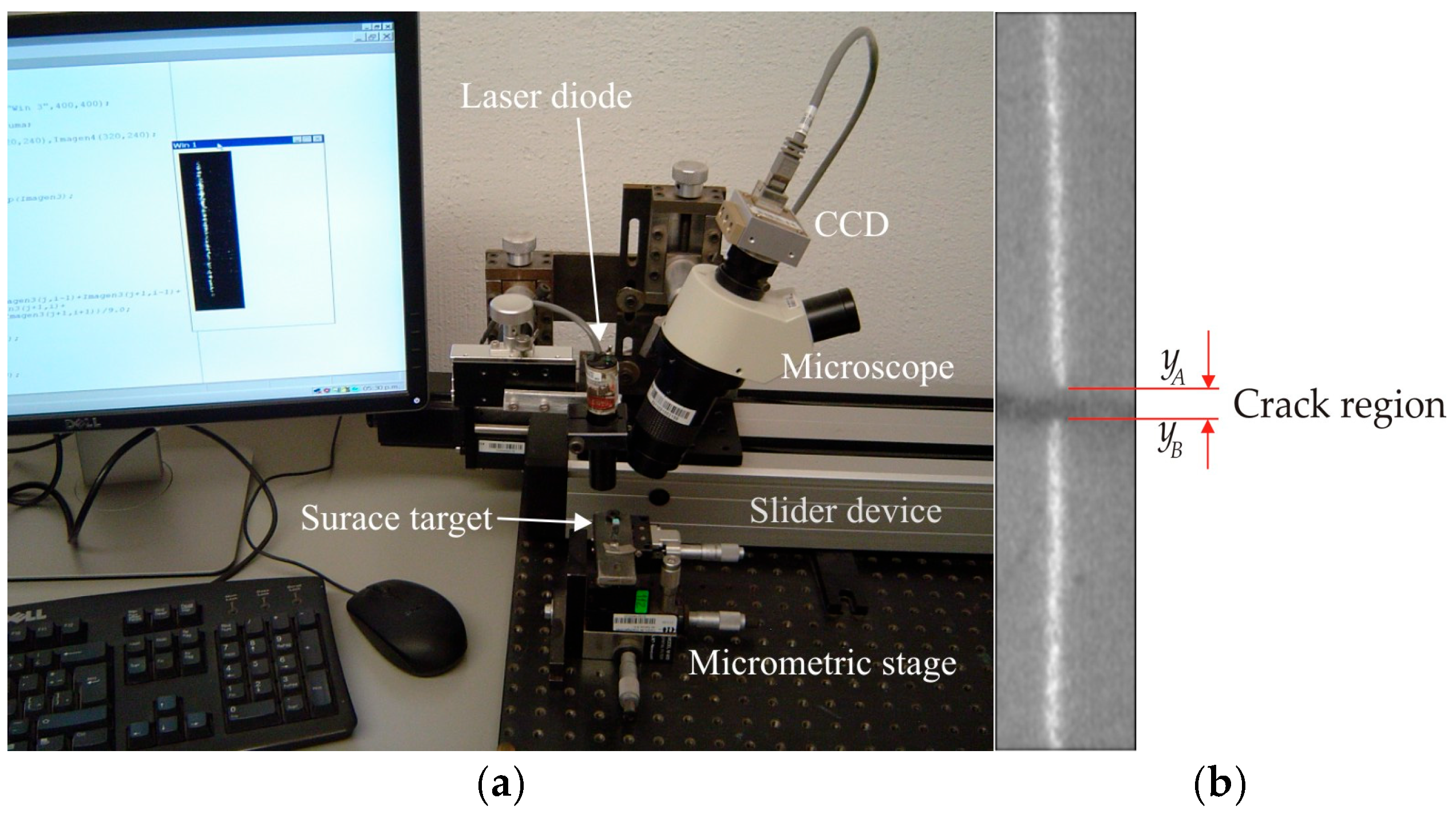

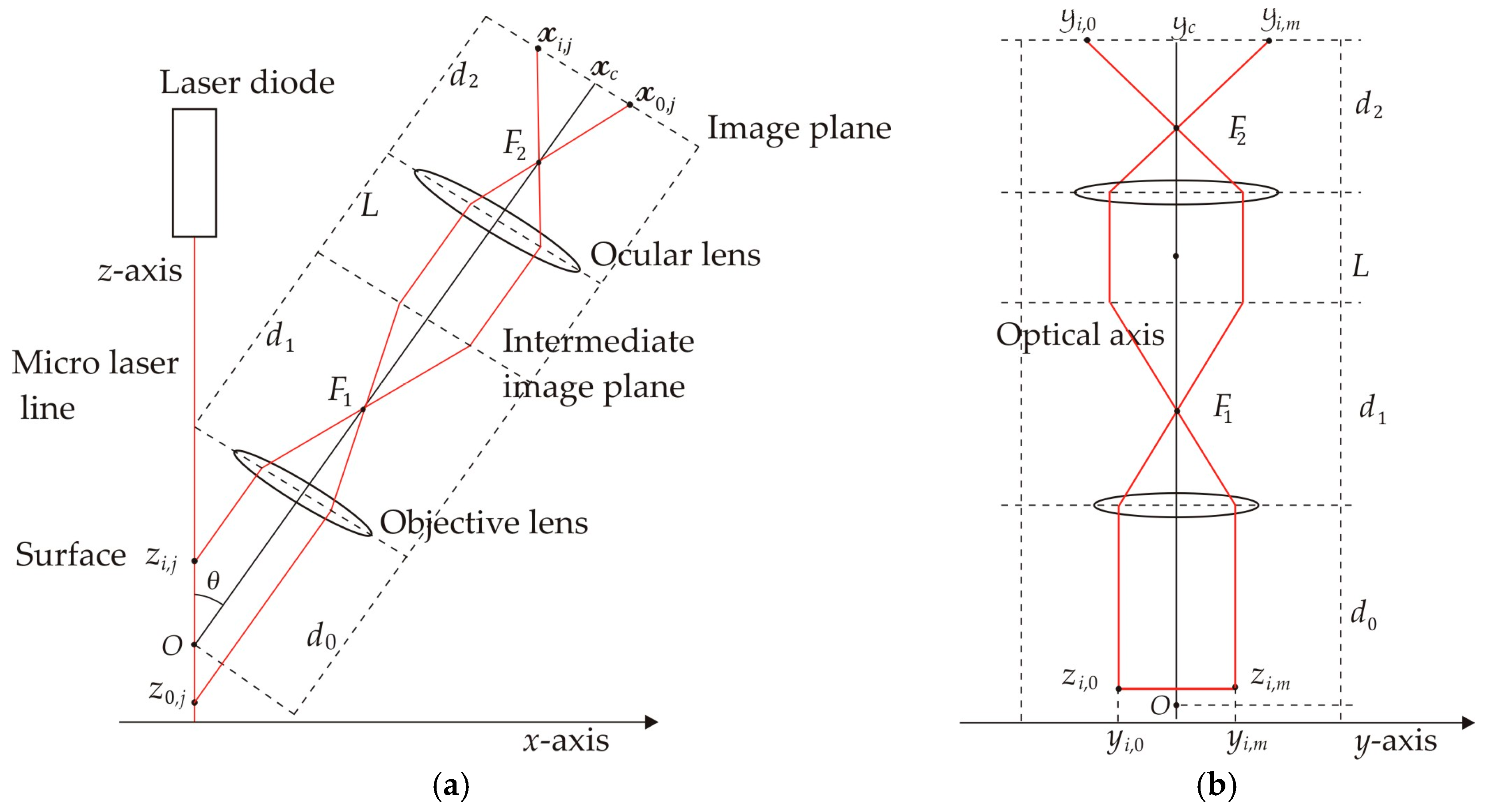

The proposed micro-scale crack contour modeling is performed using metaheuristic algorithms to determine crack areas, employing three-dimensional topography retrieved via laser line scanning. Thus, the crack contour model is developed by a metaheuristic algorithm employing Bezier functions and the coordinates of a broken laser line. Thus, the metaheuristic algorithm optimizes the Bezier functions using three-dimensional control points, which are computed by bio-inspired algorithms to generate crack contour models. Through this procedure, the crack contour model yields a three-dimensional Bezier curve, which depicts the crack contour area. The micro-scale crack contour modeling is carried out by an optical microscope vision system that includes a CCD camera and a 42 μm laser line. The microscope system is mounted on a slider device to move the vision system, which performs the scanning in the

x-axis. Thus, the micro-laser line scans the surface, while the camera captures the broken laser line images to retrieve the crack contour region. In this process, the micro-scale topography is computed using the laser line position and the microscope’s geometry. Thus, the crack contour is determined using topography coordinates, providing high accuracy to improve the conventional crack inspection performed via image processing. In this context, the proposed technique provides crack contour measurements with a relative error smaller than 2%. Also, the proposed crack contour modeling can detect crack contours with a minimum surface width of 20 microns. This crack contour modeling improves the accuracy of the crack characterization via gray-scale image processing. The enhancement is achieved through the crack contouring performed by the micro-laser line projection. Also, the crack contour modeling approach improves the accuracy of measuring the crack region. This occurs due to the calculation of the Bezier basis functions by means of the three-dimensional crack topography. The contribution of crack contour modeling is established through a discussion focused on the accuracy of the crack characterization and detection via gray-scale image processing. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: the basic theory for crack contour modeling using Bezier basis functions is described in

Section 2.1, the crack contour modeling utilizing a metaheuristic algorithm based on Bezier basis functions is presented in

Section 2.2, the recovering of crack surfaces through the broken laser line is detailed in

Section 2.3,

Section 2.4 covers the calibration of microscope parameters, the results of micro-surface crack modeling are presented in

Section 3, and the contributions of the proposed micro-scale crack modeling are discussed in

Section 4.

3. Micro-Scale Crack Contour Modeling Results

The micro-scale crack contour modeling is carried out by the microscope vision system shown in

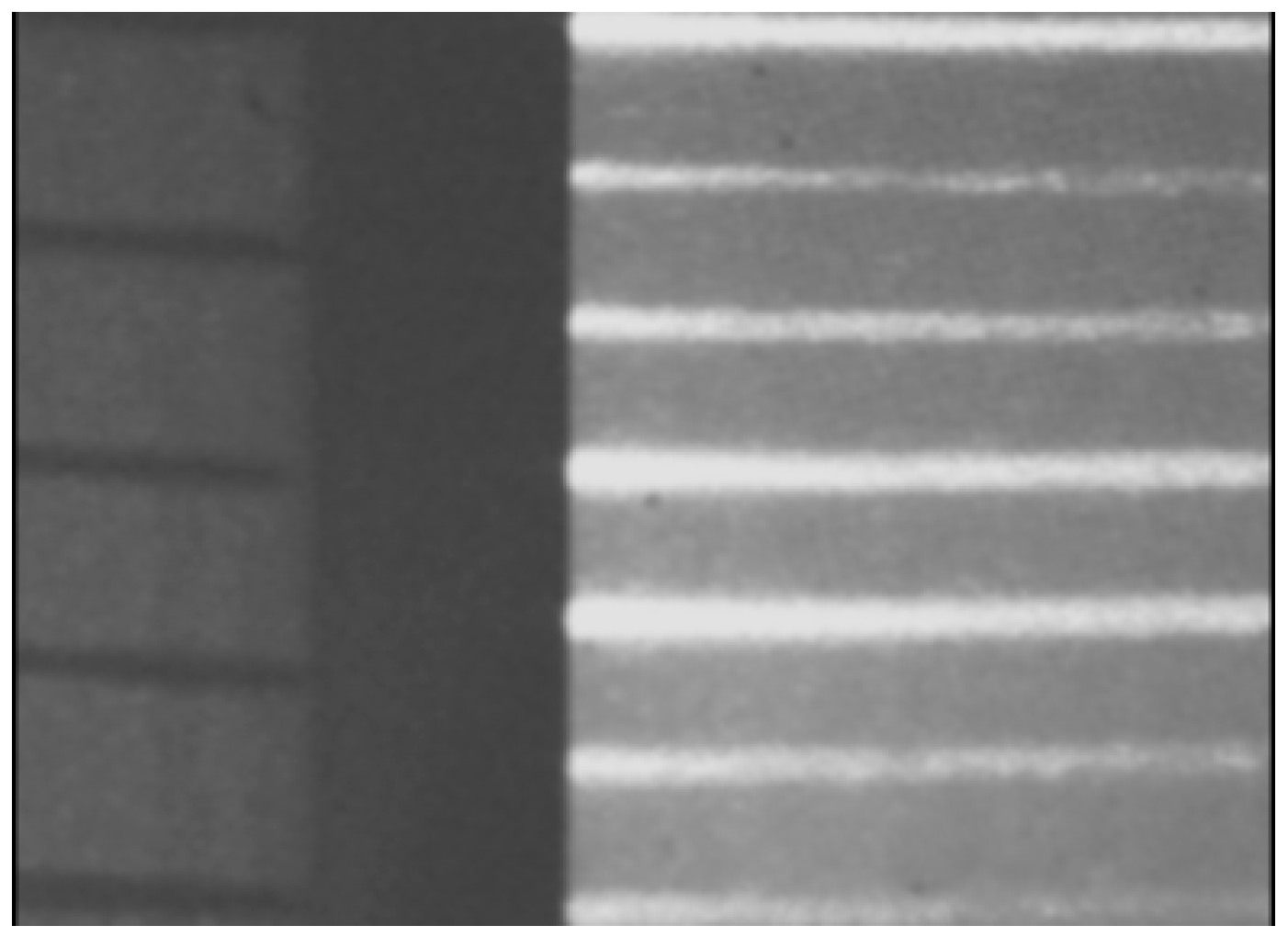

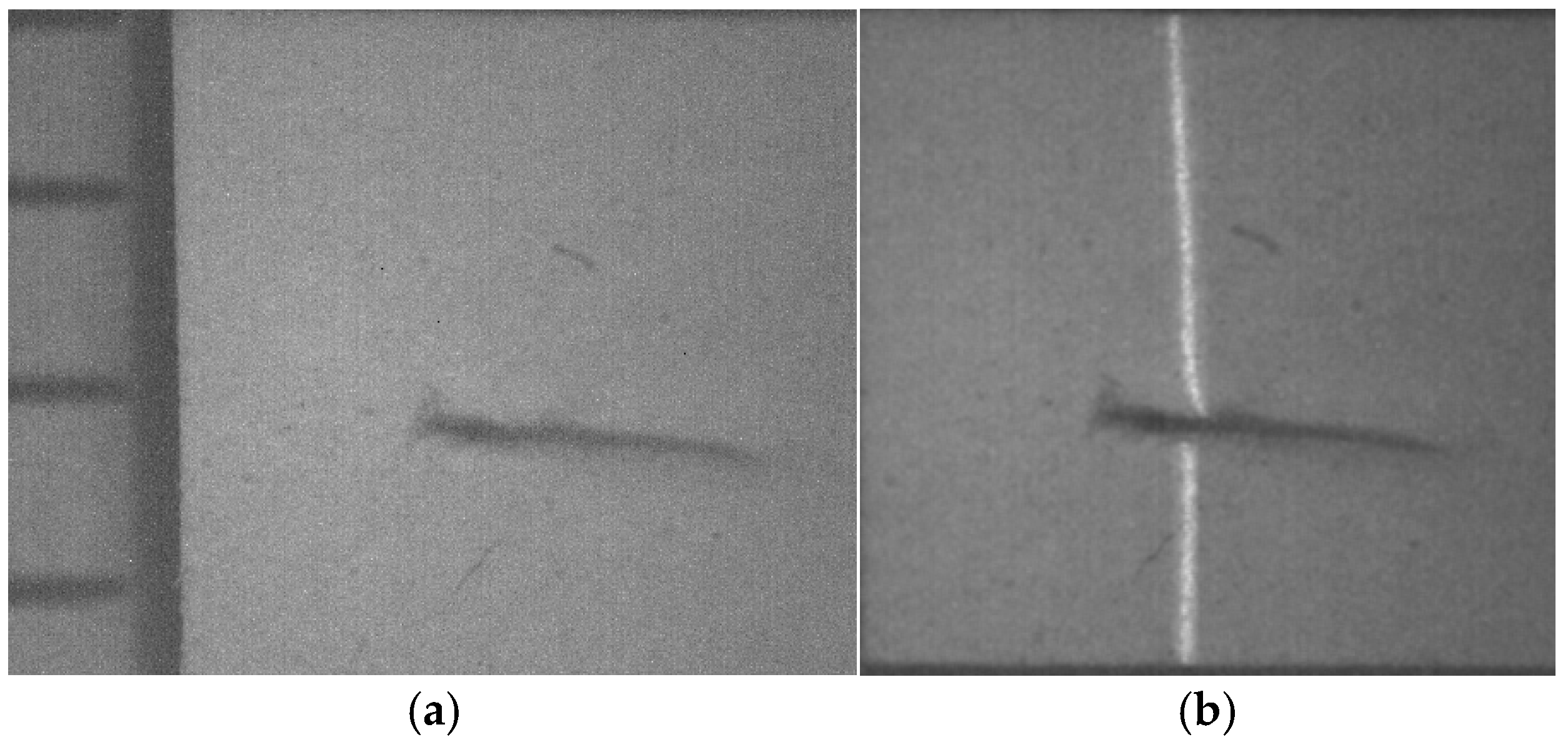

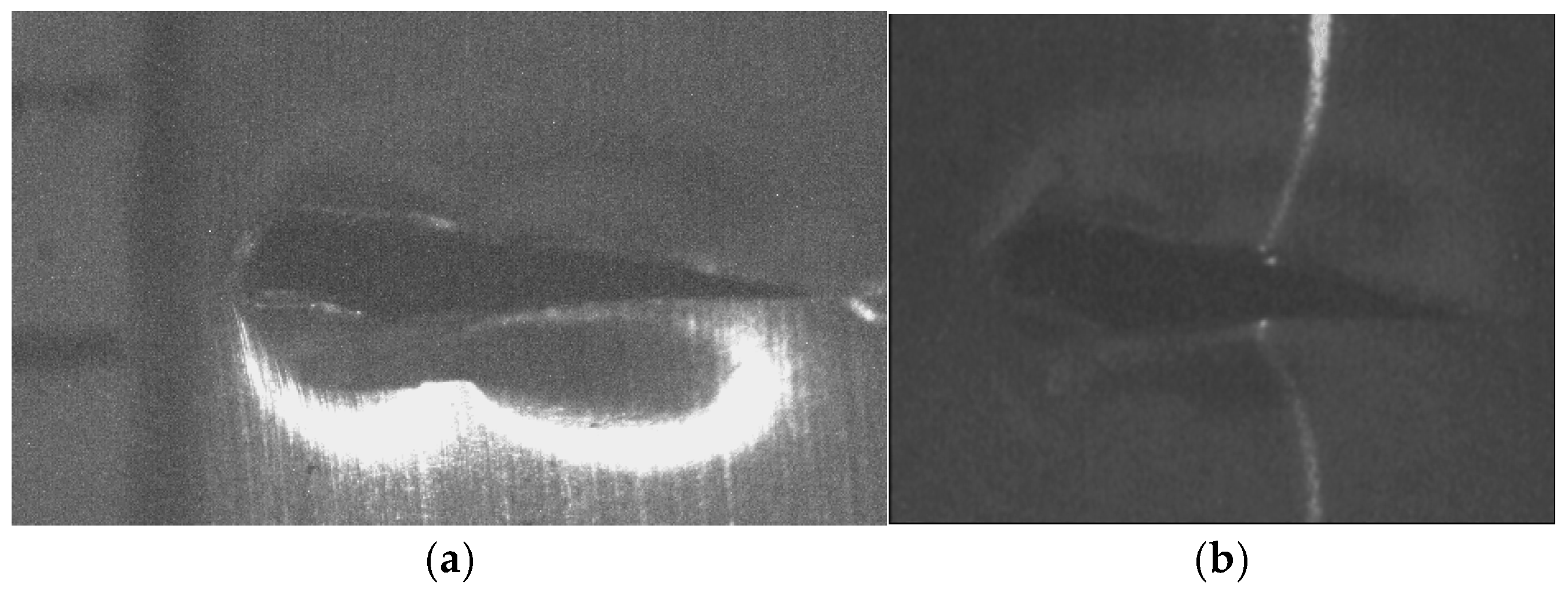

Figure 4a. Thus, the first micro-scale crack contour modeling is performed for the wood surface shown in

Figure 7a, where the scale is indicated in millimeters along the

x-axis. Also, the micro-laser line projected on the wood surface is shown in

Figure 7b, where the broken laser line indicates the crack area along the

y-axis. In this way, the wood surface is scanned along the

x-axis to determine the laser line coordinates (

xi,j,

yi,j) by computing Equations (20) and (21). Then,

xi,j is replaced in Equation (18) to compute the surface height

zi,j, while

yi,j is substituted in Equation (19) to calculate the surface width

yi,j. Additionally, the slider device provides the surface length

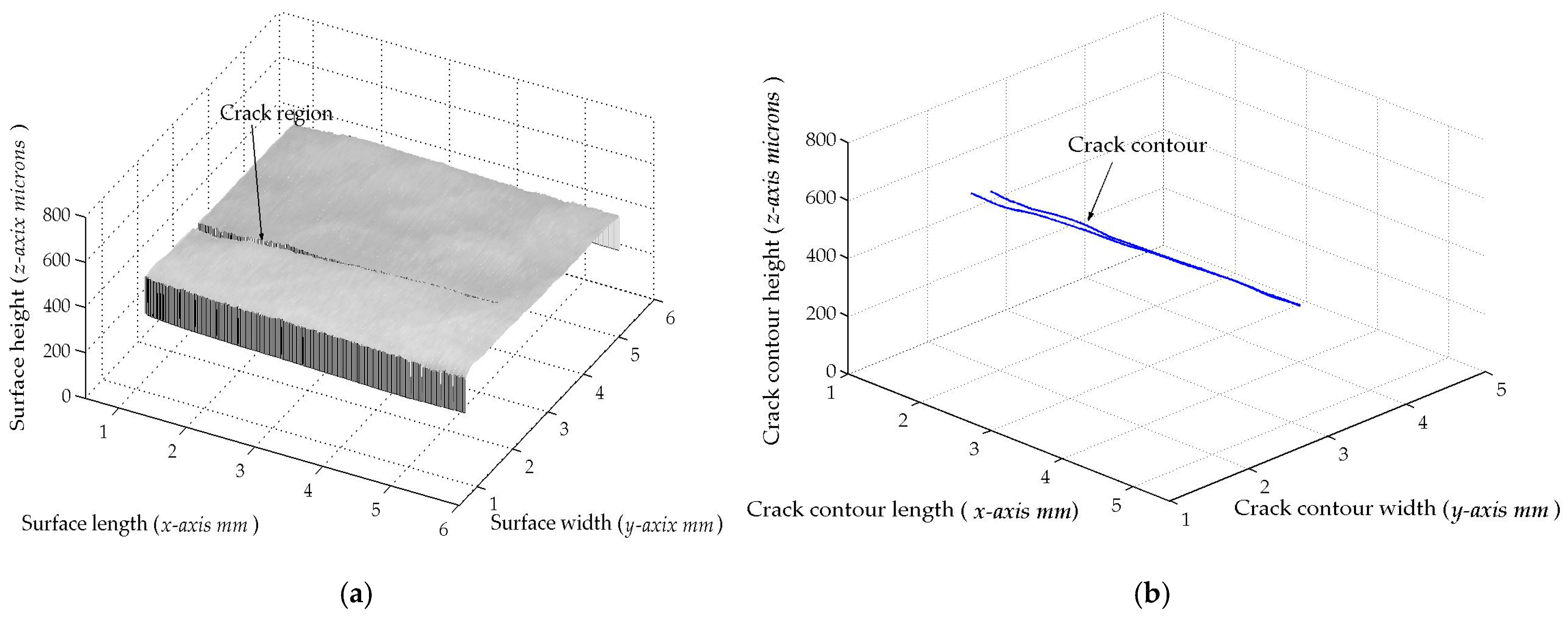

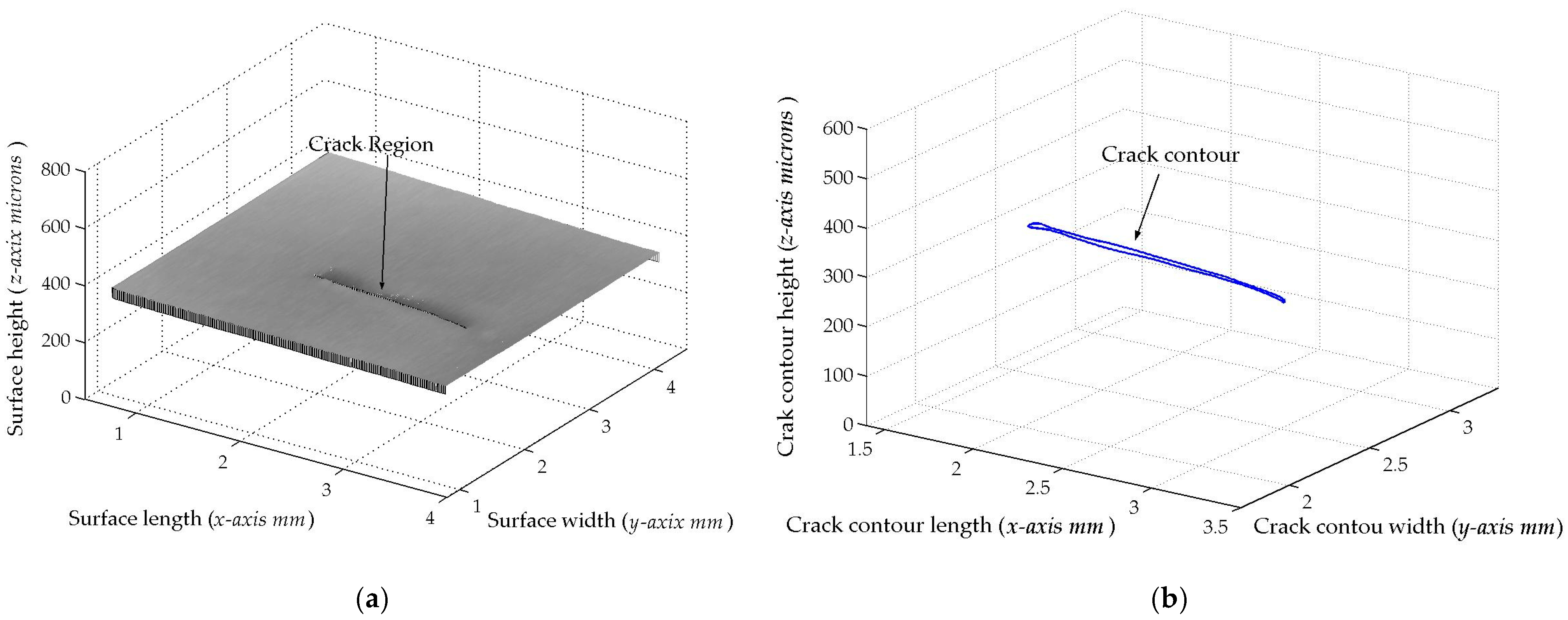

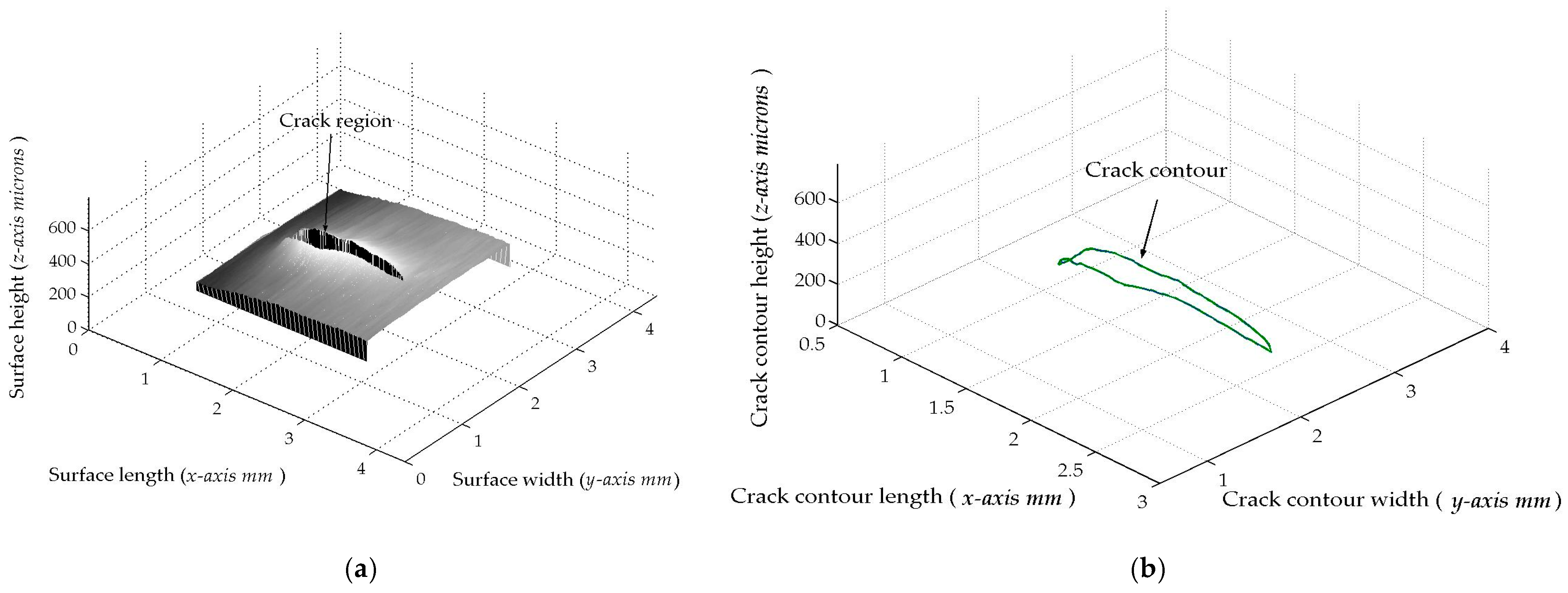

xi,j. Thus, two hundred and eighty-four images were processed of the wood surface shown in

Figure 8a, where the

x-axis and

y-axis are indicated in mm, while the

z-axis is indicated in microns. The surface-recovering accuracy is determined through the relative error [

36] with the following expression:

In this equation,

zi,j represents the surface computed via Equation (18),

hi,j denotes the surface measured through a contact method, and

n·

m is the data number. Thus, Equation (24) is computed for the wood surface illustrated in

Figure 8a, resulting in a relative error of

Er% = 1.6216%. The position of the crack contour is obtained during the surface scanning, starting from the beginning and the end of the broken laser position along the

y-axis. In this procedure, the broken laser line is identified by summing the intensity of five adjacent pixels along the

x-axis. Hence, if the intensity summation exceeds 680, the laser line exists. If not, the laser line is nonexistent. In this case, a crack region is identified, and the laser line position is not computed. But, the crack contour position is acquired from the last laser position along the

y-axis. Thus, the beginning of the crack region has been obtained along the

y-axis. Then, the procedure calculates the maximum in the subsequent rows until to it achieves an intensity summation exceeding 680. Thus, the final location of the crack region is determined in the

y-axis.

In this way, a crack region is identified when there are three rows of broken laser lines on the

y-axis and three broken laser lines on the

x-axis. Based on these criteria, the coordinates (

xi,

yj,

zi) of the broken line are acquired during the scanning of the wood surface. From these crack surface coordinates, a crack contour model is built through the metaheuristc algorithm that relies on Bezier functions as described in

Section 2.2. Thus, the first step generates the search space by computing Equations (2)–(4) employing

Pr+5s =

xr+5s,

Pr+5s =

yr+5s,

Pr+5s =

zr+5s. If

Zs(

wr) exceeds

zr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. But, if

Zs(

wr) is below

zr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1.7 and 1. Also, if

Ys(

vr) exceeds

yr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. But, if

Ys(

vr) falls below

yr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1.7 and 1. Similarly, if

Xs(

ur) exceeds

xr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. But, if

Xs(

ur) is below

xr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1.7 and 1. Subsequently, four values (

1,k,

2,k,

3,k,

4,k) are randomly selected between the maximum and minimum to obtain the initial population for each weight. Next, the second step generates the current children (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k,

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k) by computing Equations (11)–(16). Also, the control points

P1+5s = (

x0+5s +

x1+4s)/2,

P1+5s = (

y0+5s +

y1+4s)/2,

P1+5s = (

z0+4s +

z1+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

x3+4s +

x4+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

y3+4s +

y4+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

z3+4s +

z4+4s)/2 are computed to provide continuity

G1. Subsequently, the third step calculates the fitness by replacing [

Xs(

ur),

Ys(

vr),

Zs(

wr)] and [

xr,

yr,

zr] in Equation (17). Then, the fourth step determines the (

k + 1)-generation parents by selecting the parents [

1,k+1,

2,k+1,

3,k+1,

4,k+1] from [(

1,k,

2,k), (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k), (

3,k,

4,k), (

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k)]. Next, the fifth step mutates the last fit parent, introducing a new parent. Thus, if the new parent enhances the fitness, the worst parent undergoes mutation. If not, the mutation does not occur. Additionally, a new weight takes the place of a weight that is randomly selected. Thus, if the new weight improves the fitness, weight mutation takes place. In other cases, the chosen weight remains unchanged. Also, the (

k + 1)-generation children are generated by computing Equations (11)–(16). Next, steps two through five are repeated until the optimal weights that minimize the objective function Equation (17) are obtained. Thus, a fifth Bezier curve has been obtained. This procedure is carried out to compute the Bezier curves [

X0(

u),

Y0(

v),

Z0(

w)], [

X1(

u),

Y1(

v),

Z1(

w)], [

X2(

u),

Y2(

v),

Z2(

w)], [

X3(

u),

Y3(

v),

Z3(

w)], …, [

XM(

u),

YM(

v),

ZM(

w)] in order to generate the crack contour model. The contour curve provided by the crack contour model is shown in

Figure 8b. The accuracy provided by the crack contour model is computed by the following expression:

By computing Equation (25), the crack contour model produces a relative error of 0.872% for the crack contour shown in

Figure 8b. Thus, the crack contour model has been constructed by the metaheuristic algorithm.

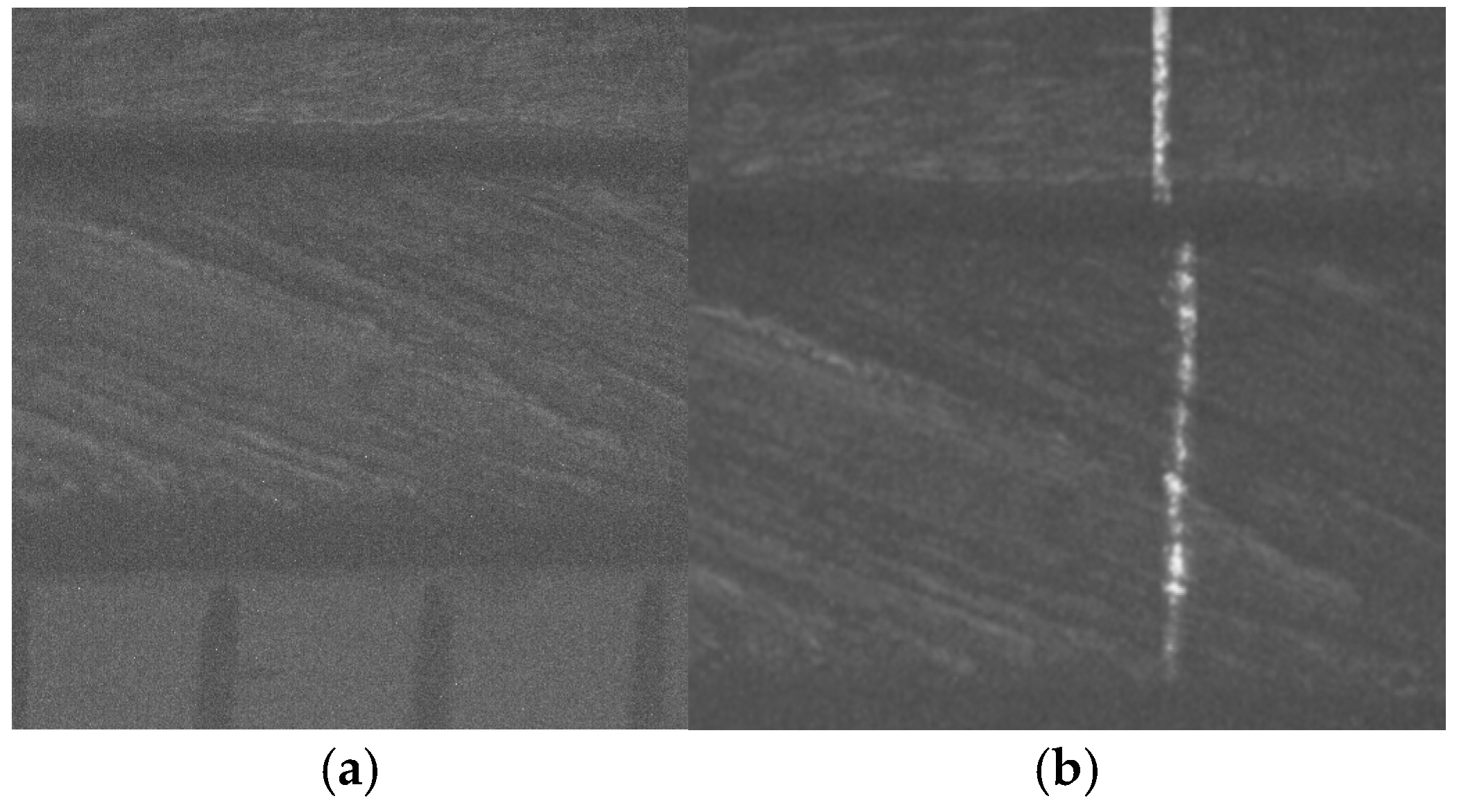

The second micro-scale crack contour modeling is performed for the paper surface shown in

Figure 9a, where the scale is indicated in millimeters along the

y-axis. Also, the micro-laser line projected on the paper surface is illustrated in

Figure 9b, where the broken laser line depicts the crack region along the

y-axis. Thus, the paper surface is scanned along the

x-axis to determine the surface height

zi,j and the surface width

yi,j by computing Equations (18) and (19) using the coordinates (

xi,j,

yi,j), respectively. Moreover, the slider device provides the coordinate

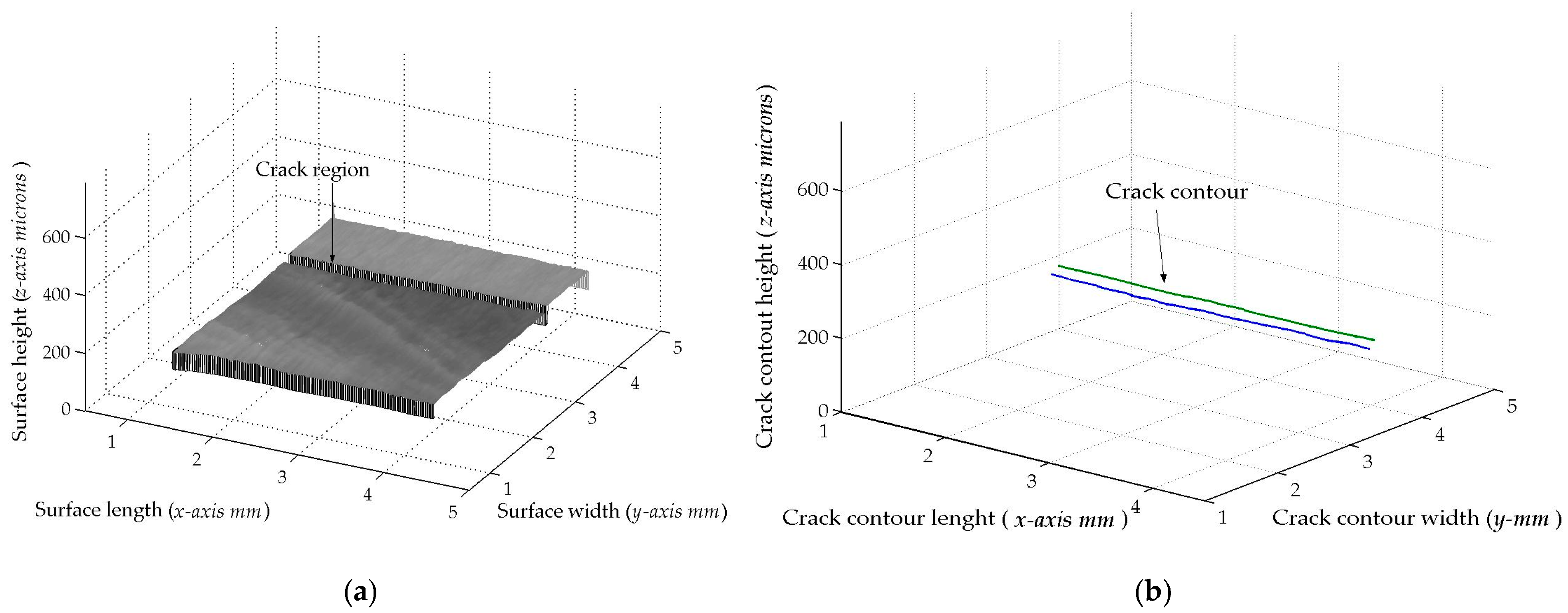

xi,j. Thus, two hundred and twenty-two images were processed of the paper surface illustrated in

Figure 10a, where the

x-axis and

y-axis are represented in millimeters, while the

z-axis is indicated in microns. The accuracy is computed by employing the surface

zi,j and the surface

hi,j provided by a contact method. Thus, Equation (24) is computed for the paper surface shown in

Figure 10a, resulting in a relative error of

Er% = 1.524%. Additionally, the coordinates of the crack surface are collected during the scanning from the beginning and end of the broken laser position along the

y-axis. In this procedure, the broken laser line is detected when the sum intensity of five adjacent pixels along the

x-axis falls below 680. When the laser line does not exist, the crack contour position is obtained from the last laser position along the

y-axis. Thus, the beginning of the crack region is obtained along the

y-axis. Next, the maximum is computed in the subsequent rows until achieving an intensity summation exceeding 680 to determine the end position in the

y-axis. Thus, a crack region is detected when there are three rows of the broken laser line in the

y-axis and three broken laser lines in the

x-axis. In this way, the broken line coordinates are computed during the paper surface scanning. Then, the crack contour model is built using the metaheuristc algorithm through the Bezier functions. Thus, the first step computes Equations (2)–(4) via

Pr+5s =

xr+5s,

Pr+5s =

yr+5s,

Pr+5s =

zr+5s to establish the initial population. If

Zs(

wr) is over

zr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. If not, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1.7 and 1. Also, if

Ys(

vr) exceeds

yr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. Otherwise, the maximum and minimum are 1.7 and 1. Additionally, if

Xs(

ur) exceeds

xr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. If not, the maximum and minimum are 1.7 and 1. Then, four values (

1,k,

2,k,

3,k,

4,k) are randomly selected between the maximum and minimum to determine the initial population for each weight. Then, the second step computes Equations (11)–(16) to obtain the current children (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k,

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k). Also,

P1+5s = (

x0+5s +

x1+4s)/2,

P1+5s = (

y0+5s +

y1+4s)/2,

P1+5s = (

z0+4s +

z1+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

x3+4s +

x4+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

y3+4s +

y4+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

z3+4s +

z4+4s)/2 are computed to provide continuity

G1.

Then, the third step computes the fitness Equation (17) based on [

Xs(

ur),

Ys(

vr),

Zs(

wr)] and [

xr,

yr,

zr]. Next, the fourth step selects the (

k + 1)-generation parents [

1,k+1,

2,k+1,

3,k+1,

4,k+1] from [(

1,k,

2,k), (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k), (

3,k,

4,k), (

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k)], respectively. Then, the fifth step performs a mutation by replacing the least fit parent with a new one. Also, a new weight replaces a weight that is selected at random. Then, Equations (11)–(16) are computed to obtain the (

k+1)-generation children. Subsequently, steps two through five are repeated until the optimal weights that minimize the objective function Equation (17) are obtained. This procedure is carried out to compute the optimal Bezier curves [

X0(

u),

Y0(

v),

Z0(

w)], [

X1(

u),

Y1(

v),

Z1(

w)], [

X2(

u),

Y2(

v),

Z2(

w)], [

X3(

u),

Y3(

v),

Z3(

w)], …, [

XM(

u),

YM(

v),

ZM(

w)] that represent the crack contour model. From this crack contour model, the crack contour shown in

Figure 10b is obtained. The accuracy provided by the crack contour model is computed via Equation (25), and the result is a relative error of 0.9612%. Thus, the micro-scale crack contour model has been built using the metaheuristic algorithm and micro-laser line scanning.

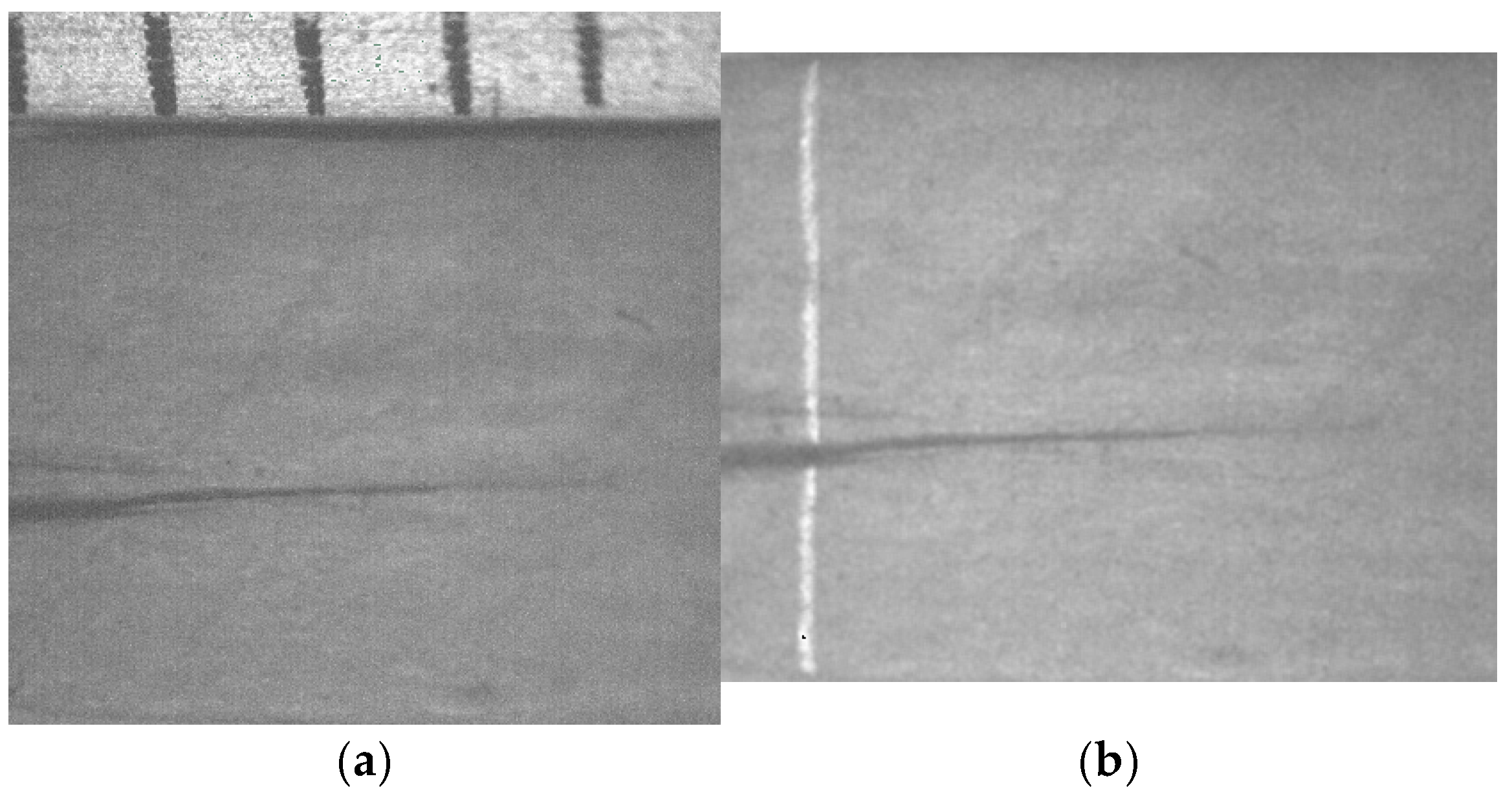

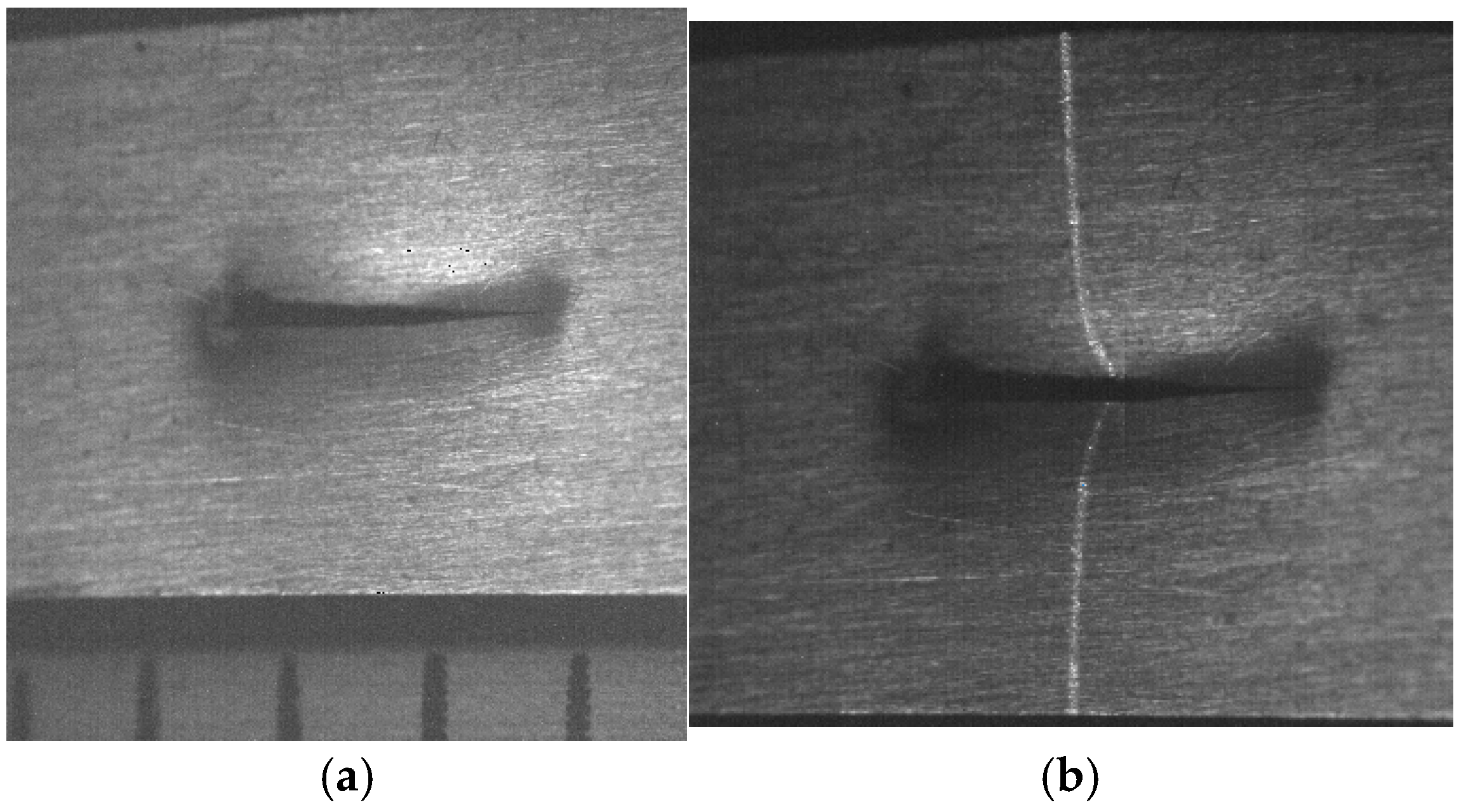

The third micro-scale crack contour modeling is performed for the metallic surface illustrated in

Figure 11a, where the scale is indicated in millimeters along the

x-axis.

Figure 11b illustrates the broken laser line within the crack region of the metallic surface along the

y-axis. Thus, the metallic surface is scanned at the

x-axis to retrieve the coordinates (

xi,j,

yi,j). At the same time, the surface height

zi,j and surface width

yi,j are retrieved by computing Equations (18) and (19) by means of the coordinates (

xi,j,

yi,j). Additionally, the slider device provides the coordinate

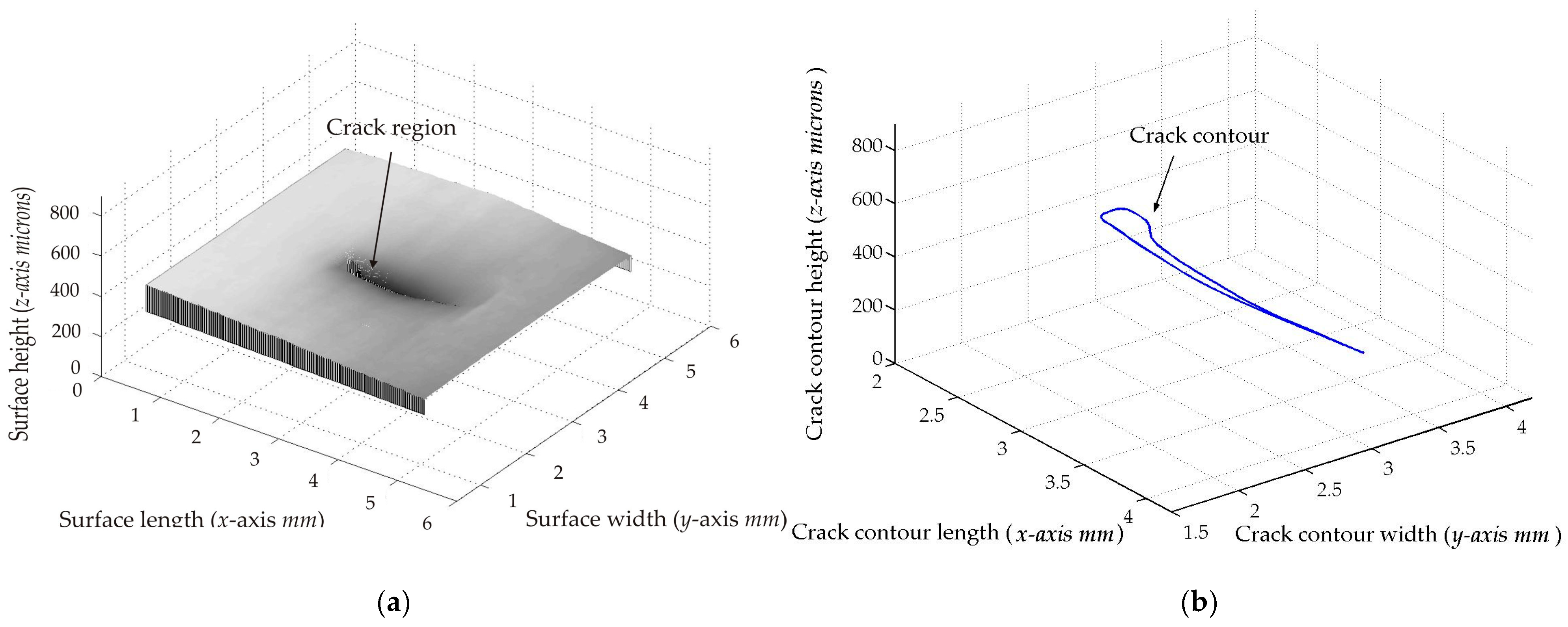

xi,j. Thus, two hundred and seventy-four images were processed of the metallic surface shown in

Figure 12a, where the

x-axis and

y-axis are indicated in millimeters, while the

z-axis is indicated in microns. The accuracy is computed via relative error using the coordinate

zi,j and the surface

hi,j measured by a contact method. Thus, Equation (24) is computed for the metallic surface shown in

Figure 12a, resulting in a relative error of 1.436%. Additionally, the coordinates of the crack surface are computed during the scanning based on the position of the broken laser line along the

y-axis. Thus, the broken laser line is detected when the sum of five adjacent pixels along the

x-axis falls below 680. Also, the crack contour position is obtained from the last laser position on the

y-axis to establish the beginning of the crack region. Then, the summation is computed in the next rows to find a value greater than 680, which determines the end position of the crack region on the

y-axis. Also, a crack region is detected when there are three rows of broken laser line on the

y-axis and three broken laser lines on the

x-axis. In this way, the broken line coordinates are obtained during the scanning. Then, the crack contour model is constructed by the metaheuristc algorithm via Bezier functions. Thus, the first step computes Equations (2)–(4) to determine the initial population. If

Zs(

wr) exceeds

zr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. Otherwise, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1.7 and 1. Also, if

Ys(

vr) exceeds

yr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. If not, the maximum and minimum are 1.7 and 1. Additionally, if

Xs(

ur) exceeds

xr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. If not, the maximum and minimum are 1.7 and 1. Then, four values (

1,k,

2,k,

3,k,

4,k) are randomly selected from the search space to obtain the initial population for each weight. Then, the second step computes Equations (11)–(16) to generate the current children (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k,

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k). Also,

P1+5s = (

x0+5s +

x1+4s)/2,

P1+5s = (

y0+5s +

y1+4s)/2,

P1+5s = (

z0+4s +

z1+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

x3+4s +

x4+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

y3+4s +

y4+4s)/2, and

P4+5s = (

z3+4s +

z4+4s)/2 are computed to provide continuity

G1.

Next, the third step computes the fitness Equation (17) employing [

Xs(

ur),

Ys(

vr),

Zs(

wr)] and [

xr,

yr,

zr]. Then, the fourth step selects the (

k + 1)-generation parents [

1,k+1,

2,k+1,

3,k+1,

4,k+1] from [(

1,k,

2,k), (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k), (

3,k,

4,k), (

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k)], respectively. Next, the fifth step performs the mutation of the worst parent and the mutation of a weight. Also, Equations (11)–(16) are computed to obtain the (

k + 1)-generation children. Then, steps two through five are repeated to obtain the optimal weights that minimize Equation (17). This procedure is carried out to compute the optimal Bezier curves [

X0(

u),

Y0(

v),

Z0(

w)], [

X1(

u),

Y1(

v),

Z1(

w)], [

X2(

u),

Y2(

v),

Z2(

w)], [

X3(

u),

Y3(

v),

Z3(

w)], …, [

XM(

u),

YM(

v),

ZM(

w)] that represent the crack contour model. Thus, the crack contour illustrated in

Figure 12b is obtained from the crack contour model. The accuracy of the crack contour model is computed via Equation (25), obtaining a relative error of 0.8964%. Thus, the micro-scale crack contour model has been constructed by the metaheuristic algorithm and micro-laser line scanning.

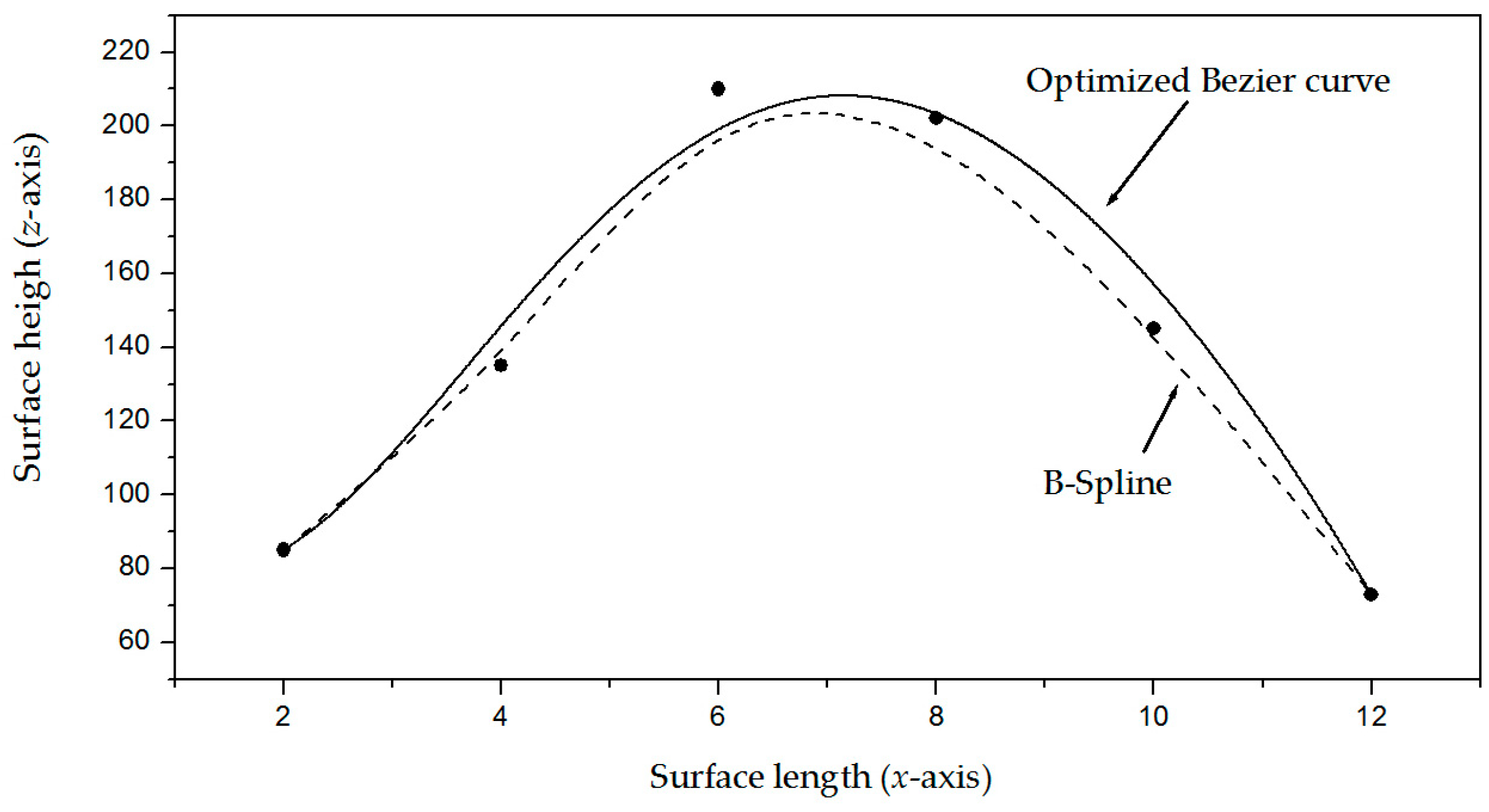

The fourth micro-scale crack contour modeling is performed for a non-planar crack surface with high reflectivity, which is shown in

Figure 13a, where the scale is represented in millimeters on the

y-axis. Additionally, the high reflectivity is illustrated by the brightness produced on the surface. This brightness produces saturation intensity in the image. The saturation intensity is detected when every pixel in a region exceeds 255. To avoid high brightness, the system reduces the light fed into the CCD array. In this way, the laser line is observed without interference with the surface brightness as shown in

Figure 13b. Also, the broken laser line indicates the crack region along the

y-axis. Thus, the non-planar surface is scanned along the

x-axis to determine the coordinates (

xi,j,

yi,j) by computing Equations (20) and (21). These equations provide a smooth curve from the pixel intensity, reducing noise in the laser line’s pixels and inaccuracies. This criterion is elucidated by the Bezier curve shown in

Figure 2. Thus, the surface height

zi,j and the surface width

yi,j are determined by computing Equations (18) and (19) using the coordinates (

xi,j,

yi,j), respectively. Additionally, the coordinate

xi,j is provided by the slider device. Thus, two hundred and forty-six images were processed of the non-planar surface shown in

Figure 14a, where the

x-axis and

y-axis are indicated in millimeters, while the

z-axis is represented in microns. The accuracy is computed by employing the surface

zi,j and the surface

hi,j provided by a contact method. Thus, Equation (24) is computed for the non-planar crack surface shown in

Figure 15a, and the result is a relative error of

Er% = 1.672%. Additionally, the coordinates of the crack surface are collected from the beginning and end of the broken laser position along the

y-axis. The broken laser line is detected when the intensity sum of five adjacent pixels along the

x-axis falls below 680. In the absence of the laser line, the crack contour position is obtained from the last laser position in the

y-axis. Next, the maximum is computed in the following rows to find an intensity sum over 680 to determine the end position on the

y-axis. Thus, a crack region is detected when there are three rows of the broken laser line along the

y-axis and three broken laser lines along the

x-axis. In this way, the broken line coordinates are computed during the scanning of the non-planar surface. Then, the metaheuristc algorithm generates the crack contour model through the Bezier functions. Thus, the first step calculates Equations (2)–(4) via

Pr+5s =

xr+5s,

Pr+5s =

yr+5s,

Pr+5s =

zr+5s to determine the initial population. If Z

s(

wr) exceeds

zr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s values are 1 and 0.3. If not, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1.7 and 1. Also, if

Ys(

vr) exceeds

yr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. Otherwise, the maximum and minimum are 1.7 and 1. Additionally, if

Xs(

ur) exceeds

xr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of

wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. If not, the maximum and minimum are 1.7 and 1. Then, four values (

1,k,

2,k,

3,k,

4,k) are randomly selected within the range of the maximum and minimum to determine the initial population for every weight. Next, the second step computes Equations (11)–(16) to obtain the current children (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k,

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k). Also,

P1+5s = (

x0+5s +

x1+4s)/2,

P1+5s = (

y0+5s +

y1+4s)/2,

P1+5s = (

z0+4s +

z1+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

x3+4s +

x4+4s)/2,

P4+5s = (

y3+4s +

y4+4s)/2, and

P4+5s = (

z3+4s +

z4+4s)/2 are computed to provide continuity

G1.

Then, the third step calculates the fitness Equation (17) employing [

Xs(

ur),

Ys(

vr),

Zs(

wr)] and [

xr,

yr,

zr]. Next, the fourth step selects the (

k + 1)-generation parents [

1,k+1,

2,k+1,

3,k+1,

4,k+1] from [(

1,k,

2,k), (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k), (

3,k,

4,k), (

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k)], respectively. Then, the fifth step performs a mutation by replacing the weakest parent with a new one. Also, a new weight replaces a weight that is randomly selected. Then, Equations (11)–(16) are computed to obtain the (

k + 1)-generation children. Subsequently, the process from steps two through five is repeated to obtain the optimal weights that minimize the objective function Equation (17). This procedure is performed to determine the Bezier curves [

X0(

u),

Y0(

v),

Z0(

w)], [

X1(

u),

Y1(

v),

Z1(

w)], [

X2(

u),

Y2(

v),

Z2(

w)], [

X3(

u),

Y3(

v),

Z3(

w)], …, [

XM(

u),

YM(

v),

ZM(

w)] that represent the crack contour model. From this crack contour model, the crack contour illustrated in

Figure 14b is obtained. The accuracy obtained from the crack contour model is calculated via Equation (25), yielding a relative error of 0.9217%. Thus, the micro-scale crack contour model has been built for the non-planar crack surface using the metaheuristic algorithm.

The fifth micro-scale crack contour modeling is performed for the textured surface shown in

Figure 15a, where the scale is indicated in millimeters along the

x-axis. Thus, the micro-laser line is projected on the texture surface as shown in

Figure 15b. This image elucidates the effectiveness of the micro-laser line width in avoiding interference with the texture surface.

Figure 15b illustrates the laser line displacement on the

x-axis due to the surface variation along the

z-axis. The sensitivity of the laser line width is deduced based on the line shifting along the

x-axis due to the surface variation along the

z-axis. Thus, the minimum surface

zi,j that produces the minimum line shifting (

xi,j,–

xc) = 1 pixel is determined based on the surface point

O. In this way, Equation (18) is computed by substituting the values of the vision parameters (

xc,

yc,

η,

θ,

d1,

F1,

d2,

F2) and (

xi,j,–

xc) = 1 to obtain

zi,j, which produces a shifting of 1 pixel along the

x-axis. The values of the vision parameters substituted in Equation (18) are described in

Section 2.4. By computing Equation (19), the result is a surface

zi,j = 4.7 microns from the surface point

O. Thus, the laser line width is allowed to determine surface variations of 4.7 microns along the

z-axis. In this way, the laser line width is allowed to make displacements along the

x-axis due to the micro-scale texture variation over 4.7 microns. This criterion is elucidated in the texture surface shown in

Figure 15b, where the laser line is displaced along the

x-axis due to the texture variation. Thus, the line displacements provide the laser line location to determine the micro-scale texture surface. Also, the broken laser line indicates the crack region along the

y-axis. In this way, the texture surface is scanned along the

x-axis to determine the coordinates (

xi,j,

yi,j) by computing Equations (20) and (21). These equations provide a smooth curve from the pixel intensity, eliminating noise in the pixels of the laser line as shown in

Figure 2. During the scanning, the surface height

zi,j and the surface width

yi,j are calculated by computing Equations (18) and (19) employing the coordinates (

xi,j,

yi,j), respectively. Additionally, the slider device provides the coordinate

xi,j. Thus, two hundred and ninety-two images were processed of the texture surface shown in

Figure 16a, where the

x-axis and

y-axis are indicated in millimeters, while the

z-axis is indicated in microns. The accuracy is determined by using the surface

zi,j and the surface

hi,j measured by a contact method. Thus, Equation (24) is calculated for the texture surface illustrated in

Figure 16a, and the result is a relative error of

Er% = 1.852%. Also, the crack surface coordinates are obtained during the scanning from the beginning and the end of the broken laser along the

y-axis. The broken laser line is identified when the sum of the intensities of five adjacent pixels along the

x-axis falls below 680. In this case, the position of the crack contour is acquired from the last laser position in the

y-axis. Next, the maximum is computed in the following rows to find an intensity sum over 680 to determine the end position of the crack along the

y-axis. Thus, a crack region is detected when there are three rows of the broken laser line pn the

y-axis and three broken laser lines on the

x-axis. In this way, the broken line coordinates are retrieved during the scanning of the texture surface. Then, the metaheuristc algorithm performs the crack contour model through the Bezier functions.

Thus, the first step computes Equations (2)–(4) via Pr+5s = xr+5s, Pr+5s = yr+5s, Pr+5s = zr+5s to obtain the initial population. If Zs(wr) is greater than zr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. If not, the maximum and minimum values of wr+5s are 1.7 and 1. Also, if Ys(vr) exceeds yr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. Otherwise, the maximum and minimum are 1.7 and 1. Additionally, if Xs(ur) exceeds xr+5s, the maximum and minimum values of wr+5s are 1 and 0.3. If not, the maximum and minimum are 1.7 and 1. Then, four values (1,k, 2,k, 3,k, 4,k) are randomly selected from the maximum and minimum to establish the initial population for every weight. Then, the second step computes Equations (11)–(16) to generate the current children (C1,k, C2,k, C3,k, C4,k, C5,k, C6,k). Also, the control points P1+5s = (x0+5s + x1+4s)/2, P1+5s = (y0+5s + y1+4s)/2, P1+5s = (z0+4s + z1+4s)/2, P4+5s = (x3+4s + x4+4s)/2, P4+5s = (y3+4s + y4+4s)/2, P4+5s = (z3+4s + z4+4s)/2 are calculated to provide continuity G1.

Then, the third step evaluates the fitness Equation (17) employing [

Xs(

ur),

Ys(

vr),

Zs(

wr)] and [

xr,

yr,

zr]. Next, the fourth step chooses the (

k + 1)-generation parents [

1,k+1,

2,k+1,

3,k+1,

4,k+1] from [(

1,k,

2,k), (

C1,k,

C2,k,

C3,k), (

3,k,

4,k), (

C4,k,

C5,k,

C6,k)], respectively. Then, the fifth step mutates the weakest parent with a new one. Also, a new weight replaces a weight that is randomly selected. Then, Equations (11)–(16) are computed to obtain the (

k + 1)-generation children. Subsequently, the process from steps two through five is repeated to obtain the optimal weights that minimize the objective function Equation (17). This procedure is performed to determine the Bezier curves [

X0(

u),

Y0(

v),

Z0(

w)], [

X1(

u),

Y1(

v),

Z1(

w)], [

X2(

u),

Y2(

v),

Z2(

w)], …, [

XM(

u),

YM(

v),

ZM(

w)], which represent the crack contour model of the crack contour shown in

Figure 16b. The accuracy obtained from the crack contour model is calculated via Equation (25), yielding a relative error of 0.945%. Thus, the micro-scale crack contour model has been built for the textured crack surface using the metaheuristic algorithm.

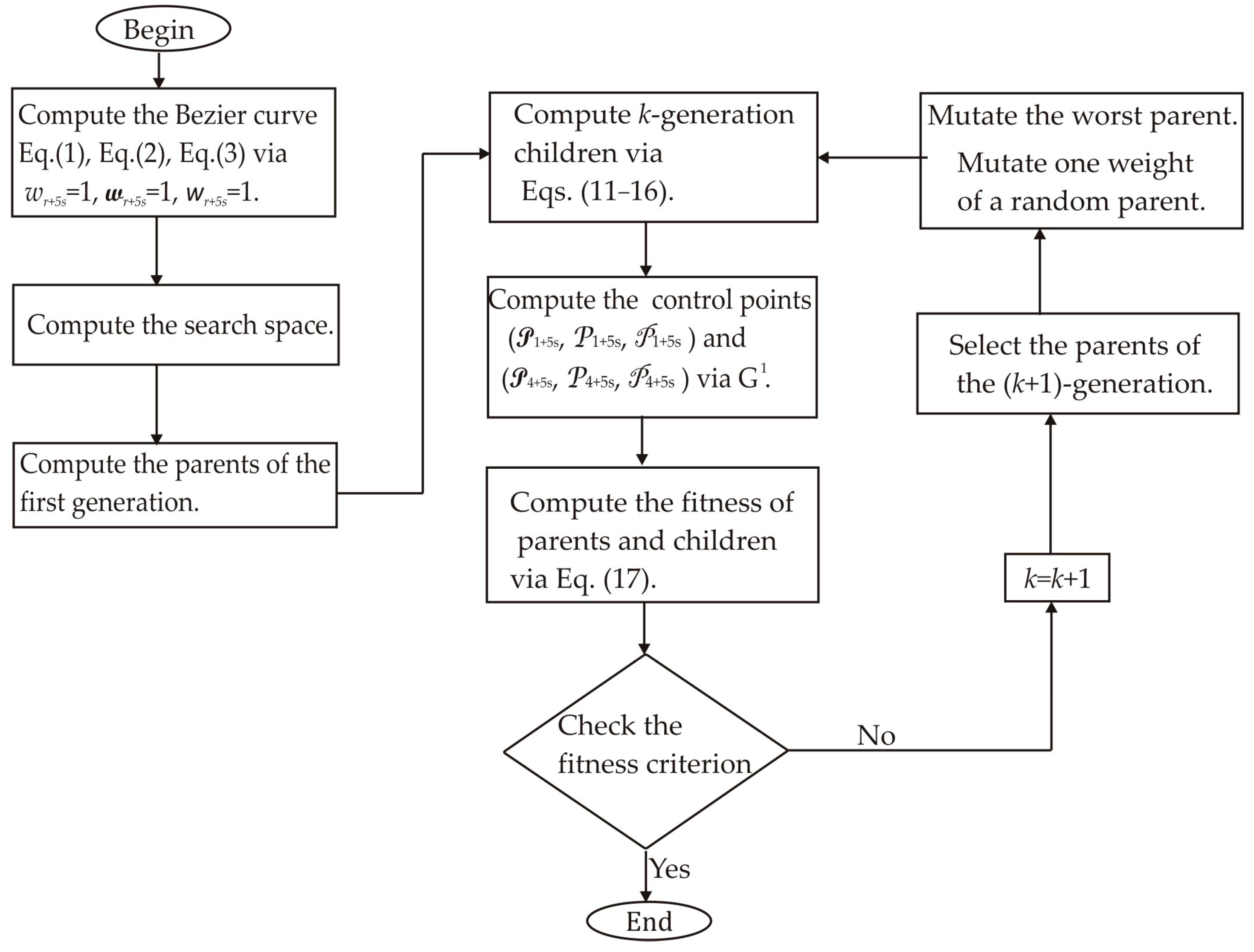

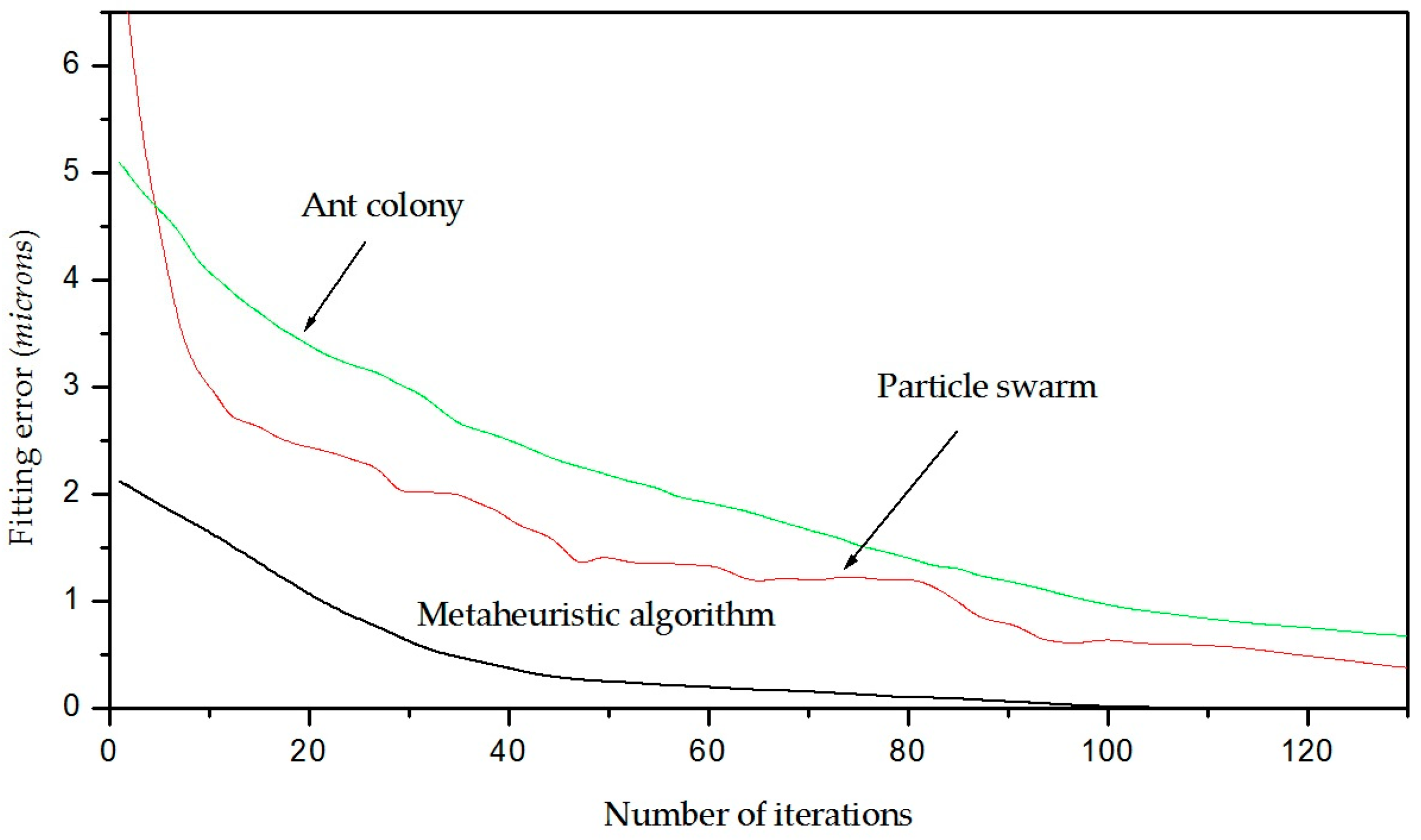

The capability of the metaheuristic algorithm is established based on the fitting accuracy of the crack contour model to represent the crack topography [

37]. This capability includes model fitting accuracy and algorithm efficiency. To elucidate these criteria, the fitting algorithm accuracy and the number of iterations are described as follows. In this way, the error of the algorithm is determined during the iterations to construct the crack contour model. This error is determined by computing the average error of the crack contour model of the wood surface, paper surface, metallic surface, non-planar surface with a high reflectance, and texture surface. From these crack contour models, the average error in the first iteration is 2.261 microns. Then, the error decreases in the next iterations, obtaining an average error of 0.000651 in iteration 108. The behavior of the error of the metaheuristic algorithm in these crack contour models is depicted in

Figure 17, where the black line represents the error of the metaheuristic algorithm during the iterations.

Also, the errors of algorithms such as particle swarm and ant colony are shown as a reference for accuracy. Based on these results, the metaheuristic algorithm provides a good fitting accuracy and efficiency. Additionally, the number of operations for one Bezier curve [Xs(ur), Ys(vr), Zs(wr)] in each iteration is established to determine the efficiency. Based on Equations (2)–(4), the number of operations to compute the expressions [Xs(ur), Ys(vr), Zs(wr)] is 153, including sums and multiplications.

The computer employed to perform the micro-scale crack contour modeling is a PC at 2.4 GHz of velocity. In this computer, 68 images are captured per second by means of the CCD camera. Also, the computer moves the slider device by means of a control software to perform the micro-laser line scanning via optical microscope. Thus, a laser line image is processed in 0.0046 s to determine the topography of a transverse section. The crack contour model for the wood surface was computed in 33.21 s. This time includes the surface scanning and the crack contour modeling. In the same way, the crack contour model for the paper surface was obtained in 31.21 s, the crack contour model for the metallic surface was determined in 33.87 s, the crack contour model for the non-planar surface of high reflectance was computed in 36.35 s, and the crack contour model for the texture surface was obtained in 37.12 s.

4. Discussion

Typically, the viability of crack modeling is established based on the accuracy in detecting and characterizing crack contour regions [

38]. In this way, the contribution of the proposed metaheuristic algorithm is established based on the accuracy of the crack contour models in representing crack regions. This statement includes the accuracy of the crack contour models and crack surface detection. In these matters, the metaheuristic algorithm generates crack contour models that accurately fit a Bezier curve toward the crack topography in efficient form. The accuracy of the crack contour models is determined by means of the relative error of Equation (25), which represents the quality gap of the algorithm. In this way, the crack contour fitting is accomplished by moving the Bezier curves toward the crack topography by means of the control points (

P,

P,

P). Thus, the metaheuristic algorithm generates crack contour models that represent crack surface contours with a relative error smaller than 1.0

%. Additionally, crack surface detection through the broken micro-laser line provides high efficiency in detecting crack regions. This is because the micro-laser line is broken in a crack region. Thus, the broken laser line determines the real crack region based on the laser line coordinates. Therefore, the crack contour model accurately represents the real crack surface contour. This procedure improves the accuracy of the inspection of crack regions to determine surface quality. Additionally, the metaheuristic algorithm’s efficiency is established based on the algorithm structure and solution quality. In this case, the metaheuristic algorithm provides a suitable structure for adjusting the crack contour model to the crack topography. This is because the metaheuristic algorithm moves the Bezier functions toward the crack surface coordinates, adjusting the crack contour model. Moreover, the research space is deduced from the crack topography to optimize the weights of the crack contour model. In this way, a good fit is achieved after the first generation. Thus, a moderated number of iterations optimizes the crack contour model, where each iteration performs 153 operations to compute the expressions [

Xs(

ur),

Ys(

vr),

Zs(

wr)] of the crack contour model. Thus, the metaheuristic algorithm achieves a moderated running time. Moreover, the micro-laser line scanning accuracy has an influence on the accuracy of the crack contour model. This is because micro-laser line projection provides good accuracy in retrieving the real crack topography. Based on these statements, the proposed metaheuristic algorithm improves the crack contour modeling of the traditional algorithms. This is because the traditional algorithms based on image intensity distribution characterize the crack models with a relative error over 8.0% [

39,

40]. Additionally, algorithms of artificial intelligence have been implemented to perform characterization of crack regions [

41]. These algorithms characterize crack regions through the traditional structure [

42] in which the research space is not deduced from the crack topography. Instead, the metaheuristic algorithm determines the solution space from the crack topography. Therefore, the metaheuristic algorithm optimizes the crack contour model based on the crack surface coordinates, where the control points move the crack contour toward the crack topography. In this way, the structure provides a low error after the first iterations. This is one difference from the traditional algorithms, which generate the initial population in random form [

43]. Also, the proposed algorithm searches inside and outside parents to find the optimal weights. This procedure avoids the elimination of potential candidates to find the optimal solution. To elucidate the contribution of the crack contour modeling, the accuracy of the traditional crack characterization methods is as follows. Typically, crack modeling and detection are performed with a relative error over 8% by means of the traditional optical microscope systems [

44], where the crack surface data are determined through gray-scale microscope images. Therefore, the traditional optical microscope techniques characterize the crack regions through the image intensity distribution [

45]. Therefore, these microscope imaging systems do not characterize the crack region in accurate form. This is because the intensity profile does not accurately characterize the crack topography. Instead, the micro-laser line accurately depicts the crack topography via microscope images. Therefore, the crack is always detected through the broken micro-laser line. This statement has been elucidated through the crack surface detection shown in

Section 3, where the crack contour models were fitted with a relative error of 0.945%. On the other hand, the characterization and detection accuracy of the traditional algorithms is computed by the expression Accuracy = (TP + TN)/(TP + FP + TN + FN), where TP indicates the true positives, FP represents the false positives, TN depicts the true negatives, and FN represents the false negatives. For instance, crack characterization via Gaussian filtering provides a relative error over 8% for crack modeling and detection [

46]. Also, crack characterization via homomorphic filtering performs crack contouring and detection with a relative error over 8% for [

47]. In the same way, Laplacian–Gaussian filtering performs crack contouring and detection with a relative error over 8% [

48]. Moreover, crack modeling via segmentation performs crack contouring and detection with a relative error over 8% [

49]. Also, skeletonization based on segmentation performs crack contour characterization with a relative error over 8% [

50]. Furthermore, frequency domain methods yield crack contouring with a relative error over 8% [

51]. In this field, the Fourier transform method carries out crack modeling with an accuracy of 86% [

52]. On the other hand, deep learning methods realize crack contouring with a relative error over 8% [

53]. In this field, convolutional neural networks perform crack modeling with an accuracy of 90% [

54]. Also, crack contour edge detection via convolutional neural networks achieve an accuracy of 92% [

55]. But, residual neural networks perform crack contour modeling with a relative error over 8% [

56]. Also, crack contour edge detection via YoloV8 is achieved with an error of 5% [

57]. Based on these statements, it is established that the proposed metaheuristic algorithm and micro-laser projection enhance the accuracy of traditional crack characterization and detection.

Additionally, the proposed metaheuristic algorithm was examined based on traditional metaheuristic algorithms such as particle swarm and ant colony. To accomplish this, the accuracy of crack characterization and detection of traditional metaheuristic algorithms was examined. The particle swarm algorithm achieves crack characterization and detection with a relative error over 8% [

58]. Moreover, ant colony optimization performs crack contouring and detection with a relative error over 8% [

59]. Also, the metaheuristic algorithm structure was examined based on the particle swarm structure, which is very useful in the contour curves optimization [

60]. The particle swarm method computes the velocity and position of a particle to determine the population of each generation. Thus, the expression

Vi(

t + 1) =

wVi(

t) +

αR1[

Pbg(

t) −

Pi(

t)] +

βR2[

Pbi(

t) −

Pi(

t)] computes the velocity of the particle, where

w is an inertia weight,

t is the number of iterations, (

α,

β) represent the learning factors, and (

R1,

R2) are selected in random form in the interval from 0 to 1. The position of the particle is computed by the expression

Pi(

t + 1) =

Pi(

t) +

Vi(

t + 1). Therefore, the particle swarm computes five parameters to create the population in each

k-generation. But, these additional parameters are not related to the crack topography. Based on these statements, the metaheuristic algorithm and particle swarm structure can be examined to build crack contour models. To do this, the particle swarm can be utilized based on the contour models of the wood surface, paper surface, metallic surface, surface with high reflectance, and texture surface. Thus, the first examination involves the initial population, where the particle swarm randomly selects the range of the particles. Instead, the metaheuristic algorithm determines the range of every weight by computing Equations (2)–(4) based on the surface topography. Thus, the range of each particle is defined as [−2, 2] to compute the initial particles. But, the first step of the metaheuristic algorithm determines the range of every weight based on the initial Bezier curve and crack surface as described in

Section 2.2. From this stage, the metaheuristic algorithm produces smaller errors after the first iteration. The second examination is the number of tested particles, where the particle swarm initially defines the number of particles. This procedure leads to falls in a local minimum. Instead, the metaheuristic algorithm begins with four parents, but a new parent and a new weight are tested in each new generation to avoid a local minimum. This procedure is performed by the mutation described in

Section 2.2. Thus, 40 particles are defined to perform the particle swarm, and the metaheuristic algorithm tests 240 potential candidates. The third assessment is the population for the next iteration, where the particle swarm computes

Vi(

t + 1) and

Pi(

t + 1). In this case, the metaheuristic algorithm determines the children by computing Equations (11)–(16). Thus, the particle swarm computes 84 operations for six parameters, and the metaheuristic algorithm computes 36 operations. In this case, the metaheuristic algorithm provides the population of each

k-generation from crack topography through the parameters (

β,

α). Thus, the metaheuristic algorithm implements a suitable structure to obtain the next generation. The fourth examination is the selection, where the particle swarm selects the individual and global best. But, the metaheuristic algorithm selects the best parents and children. The fifth examination is the fitness error, where the particle swarm begins with a bigger error and slowly decreases. In this case, the particle swarm establishes the number of iterations since the beginning, interrupting the procedure at bigger errors. Instead, the error of the metaheuristic algorithm begins with a smaller error and decreases in moderated form. The error of the particle swarm is depicted in

Figure 17 by the red line. Also, the error of the metaheuristic algorithm in every generation is depicted in

Figure 17 by the black line.

Also, the metaheuristic algorithm can be examined based on the ant colony optimization regarding fitting accuracy and structure efficiency. In this case, the fitting accuracy of the ant colony is over 3% and computes more variables than the metaheuristic algorithm to determine crack contour models. Thus, the metaheuristic algorithm elucidates the viability to construct crack contour models with a relative error smaller than 1%. To corroborate these statements, the metaheuristic algorithm can be compared to the ant colony optimization of the crack contour models [

Xs(

ur),

Ys(

vr),

Zs(

wr)], where the contour curves include wood surface, paper surface, metallic surface, surface with high reflectance, and texture surface. In this way, the ant colony structure is compared to the metaheuristic algorithm as follows. Thus, the first examination is the initial population, where the ant colony defines the range of the ants as a discrete set. Thus, the number of ants is six with a range of [0, 3], and their discrete values have the same probability. Instead, the metaheuristic algorithm determines the range of every weight by computing Equations (2)–(4) based on the surface topography. From this stage, the metaheuristic produces a smaller error in the first iteration. Also, the efficiency is elucidated by the search space, which provides the population near the optimal solution. This procedure reduces the number of iterations to construct the crack contour model. The second examination is the number of tested ants, where the ant colony initially defines the number of ants. This procedure leads to fall in a local minimum. Instead, the metaheuristic algorithm tests a new parent and a new weight in each generation through the mutation to avoid a local minimum. The third assessment is the population for the next iteration, where the ant colony computes the pheromone evaporation τ

new = (1-evaporation rate)τ

old, the pheromone deposit (Deposit/Objective function), and a probability function

Pi = τ

i./Σ τ

j. In this case, the metaheuristic algorithm determines the children by computing Equations (11)–(16). Thus, the ant colony computes 54 operations for six parameters, and the metaheuristic algorithm computes 36 operations. The fourth examination is the selection, where the ant colony selects the higher probability. But, the metaheuristic selects the best parents and children. The fifth evaluation is the fitness error, where the ant colony begins with a bigger error and decreases slowly. Instead, the error of the metaheuristic algorithm begins with smaller error and decreases in moderated form. The error of the ant colony is shown in

Figure 17 by the green line.

Additionally, the metaheuristic algorithm is examined based on the simpler cubic B-splines. To do this, the B-splines generate the crack contour curves of the wood surface, paper surface, metallic surface, surface with high reflectance, and texture surface. Thus, the B-splines generate the contour curve through the expression

C(

t) = Σ

PiNi,3(

t), where

Pi contains the three-dimensional coordinates,

Ni,3 (

t) are basis functions, and

t is a point on the curve. In this way, the basis functions are computed by the expression

Ni,3(

t) = (

t −

ui)(

Ni,3-1(

t))/(

ui+3 −

ui) + (

ui+3+1 −

t)(

Ni+1,3-1(

t))/(

ui+3+1 −

ui+1) [

61]. Thus, the three-dimensional

B-spline curve is computed by

Cx(

t) = Σ

xiNi,3 (

t),

Cy(

t) = Σ

yiNi,3 (

t), and

Cx(

t) = Σ

ziNi,3 (

t). The accuracy provided by the B-splines method is a relative error of 2.84%. Instead, the metaheuristic algorithm generates crack contour models, which represent crack surface contours with a relative error smaller than 1.0

%.

Moreover, the metaheuristic algorithm is examined based on the least squares optimization as shown in

Figure 2. To carry this out, the least squares method computes the weights of the crack contour curves [

Xs(

ur),

Ys(

vr),

Zs(

wr)] of the wood surface, paper surface, metallic surface, surface with high reflectance, and texture surface. Thus, the least squares method computes the weights by minimizing the error between the crack coordinates and the Bezier functions, where the error is defined by the expressions e

x = Σ[xi −

xs(

ui)]

2, e

y = Σ[

yi −

ys(

vi)]

2, e

z = Σ[

zi − z

s(

wi)]

2. From these errors, the derivatives ∂e

x/∂

wi = 0, ∂e

y/∂

wi = 0, ∂e

z/∂

wi = 0 are computed to minimize the error. Expanding the summations of these derivatives, an equation system is obtained for each derivative, where each element of the equation system is a summation. Then, the systems of equations are solved to obtain the weights [

wi,

wi,

wi]. Thus, least squares method computes the crack contour curves with a relative error of 3.167%, which is bigger than error of the metaheuristic algorithm. Additionally, the leas squares method performs more operations than the metaheuristic algorithm. This is because the systems of equations are deduced by summations.

Furthermore, the clothoids structure performs more operations than the Bezier curves through the cosine and sine functions. This is because the sine and cosine are determined by a summation of multiplications and divisions. Also, the curvature should be optimized to reduce the fitting error. But, the procedure to compute the curvature is performed by a great number of operations. Therefore, Bezier curves have been employed to optimize clothoids [

62].

Additionally, the method based on peak–valley fails because the intensity profile does not provide the real surface topography. This criterion is elucidated by the surface of high reflectivity shown in

Figure 13a, where the pick intensity is not located in the peak surface. Instead, the laser line projection depicts the real surface profile as shown in

Figure 13b.

From these statements, the contribution of the crack contour modeling via the metaheuristic algorithm and micro-laser lane projection has been validated. Moreover, the simple setup increases the capability of the metaheuristic algorithm to perform crack contour modeling for surface quality inspection. This is because the arrangement includes only simple components such as a laser diode, CCD camera, slider device, and a computer. In this way, the proposed surface technique provides a contribution in the field of crack modeling and detection.