Enhancing Flight Connectivity via Synchronization of Arrivals and Departures in Hub Airports with Evolutionary and Swarm-Based Metaheuristics

Abstract

1. Background

2. Literature Survey

3. Problem Definition

4. Istanbul Airport Case

5. Solution Methods

5.1. Mathematical Model for Synchronization of Arrivals and Departures

| (1) | ||

| Subject to | ||

| i = 1, …, 5 | (2) | |

| j = 1, …, 5 | (3) | |

| i = 1, …, 5 | (4) | |

| j = 1, …, 5 | (5) | |

| p = 1, …, 5 | (6) | |

| p = 1, …, 5 | (7) | |

| (8) | ||

| Max {, 0} | i = 1, …, 5 j = 1, …, 5 i ≠ j | (9) |

| = | i = 1, …, 5 j = 1, …, 5 i ≠ j | (10) |

| i = 1, …, 5 j = 1, …, 5 | (11), (12) | |

| p = 1, …, 5 | (13), (14) | |

| i = 1, …, 5 j = 1, …, 5 p = 1, …, 5 | (15), (16) | |

| All variables ≥ 0, , are integer variables | ||

| i = 1, …, 5 | : | Arrival points (1, …, 5) |

| j = 1, …, 5 | : | Departure points (1, …, 5) |

| : | (0–5, 5–10, 10–15, 15–20, 20–25) = Flight time slots (T1, T2, T3, T4, T5) “In the LINGO model, the time slot 0–5 is assumed to correspond to an arrival or departure occurring at time 5.” | |

| = 0 or 1 | : | Binary variable for arrival from point i at time p |

| = 0 or 1 | : | Binary variable for departure to point j at time p |

| : | Number of arrivals at time p should be less than or equal to 2 | |

| : | Number of departures at time p should be less than or equal to 2 | |

| = 1 | : | There is only 1 flight from every arrival point |

| = 1 | : | There is only 1 flight to every departure point |

| : | Passenger demand from i to j | |

| : | Time difference between arrival i and departure j (Negative values = zero) | |

| Rij | : | |

| : | Number of passengers transferred from i to j |

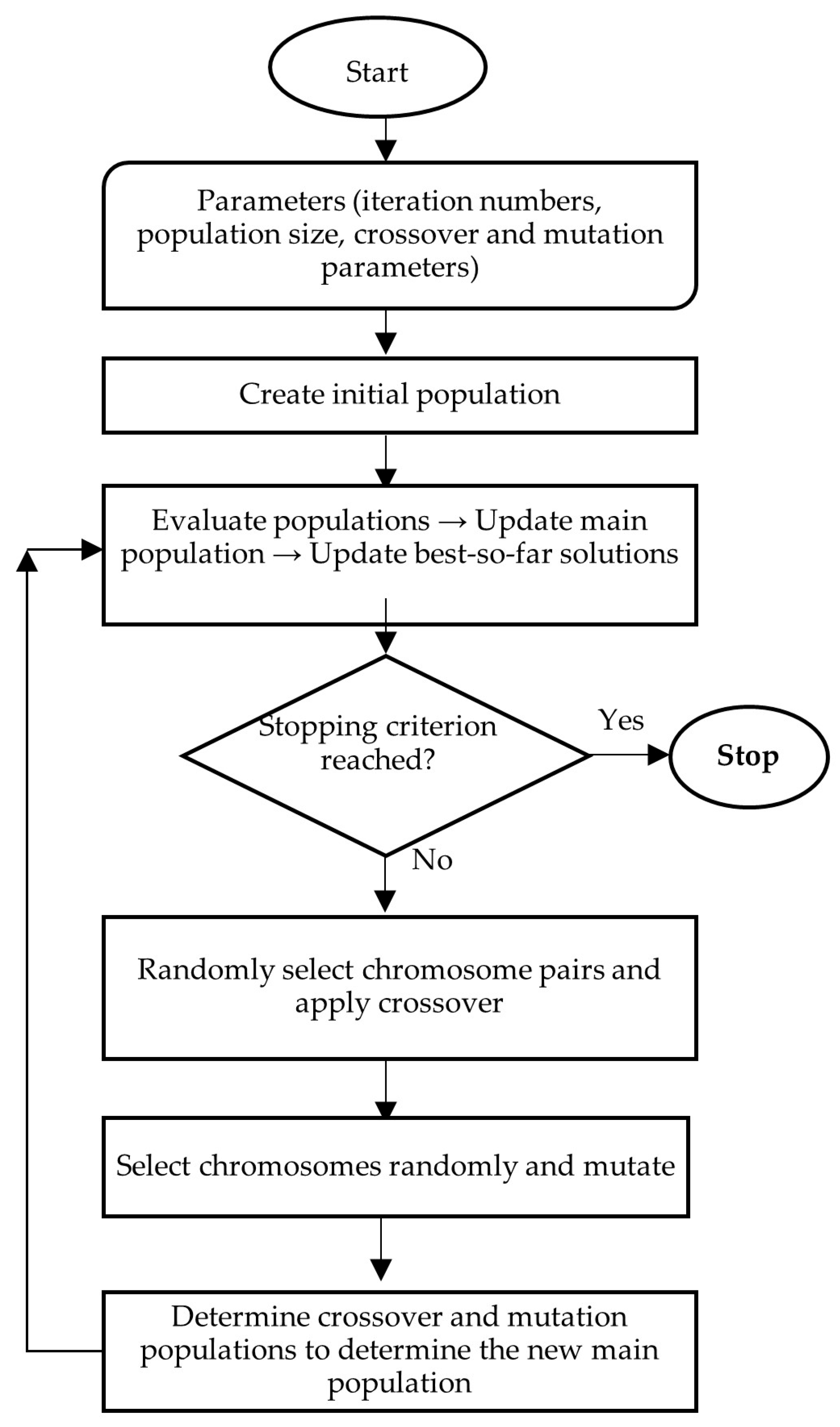

5.2. Genetic Algorithms (GA)

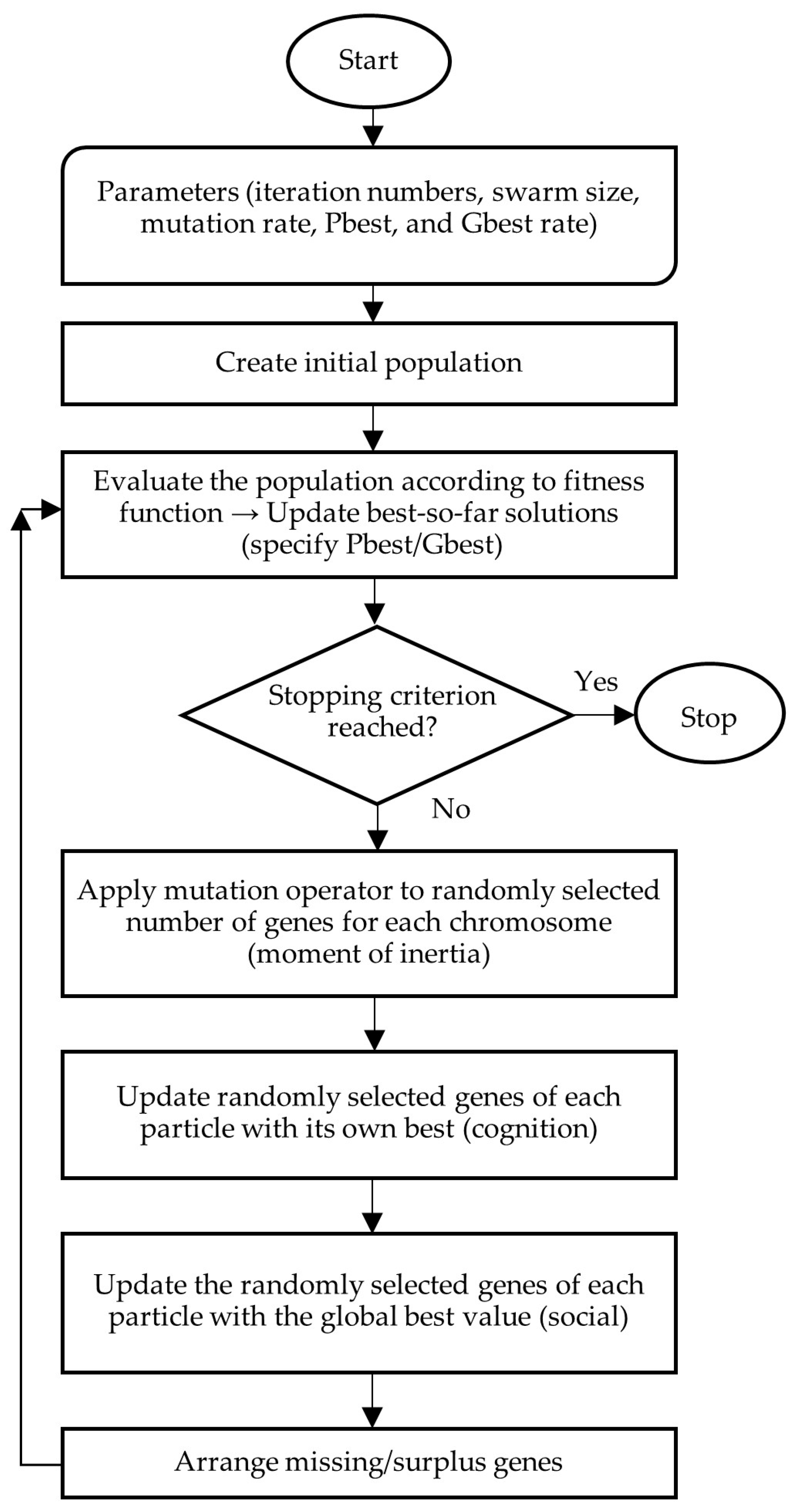

5.3. Modified Discrete Particle Swarm Optimization (MDPSO)

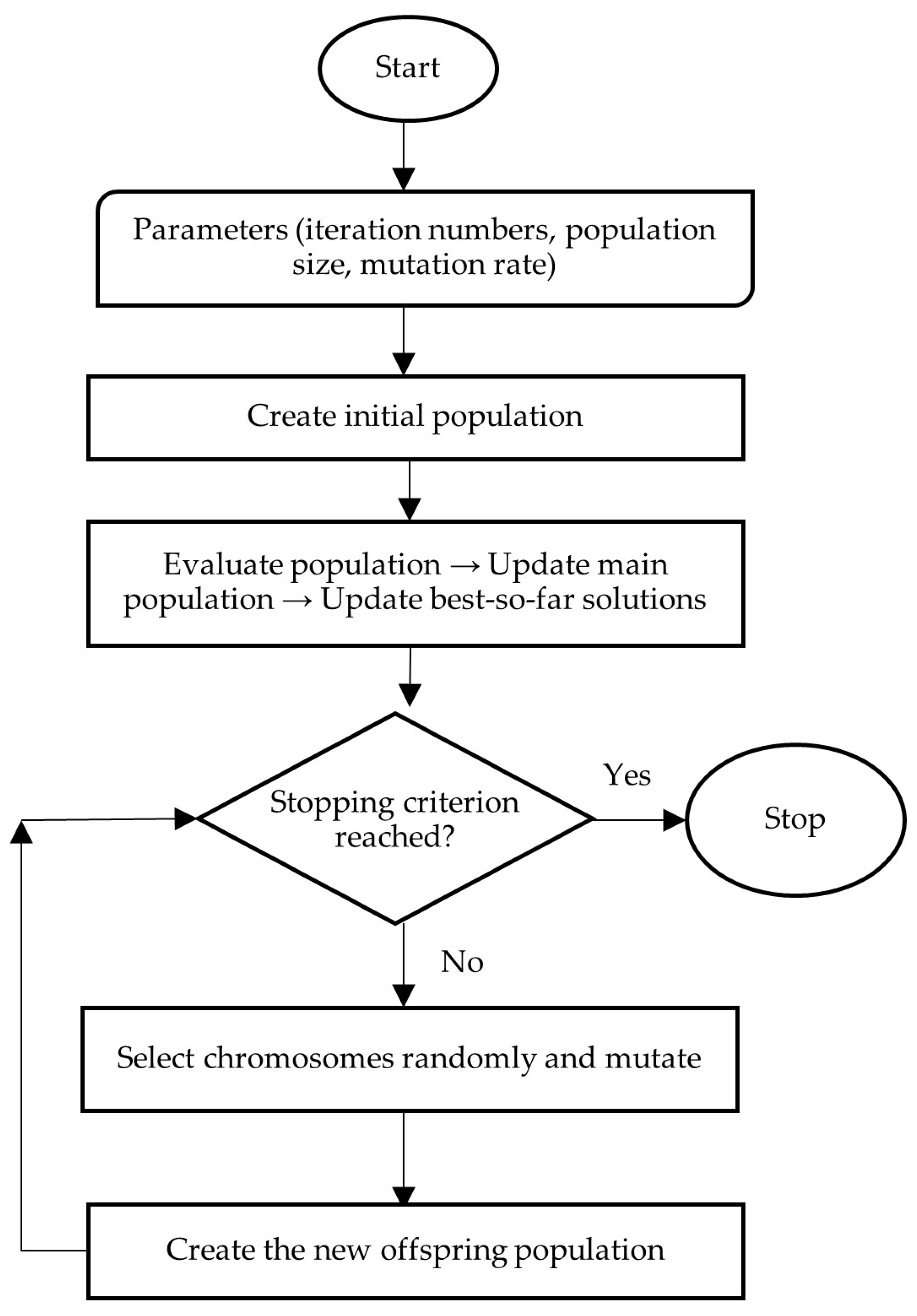

5.4. Evolutionary Strategies (ES)

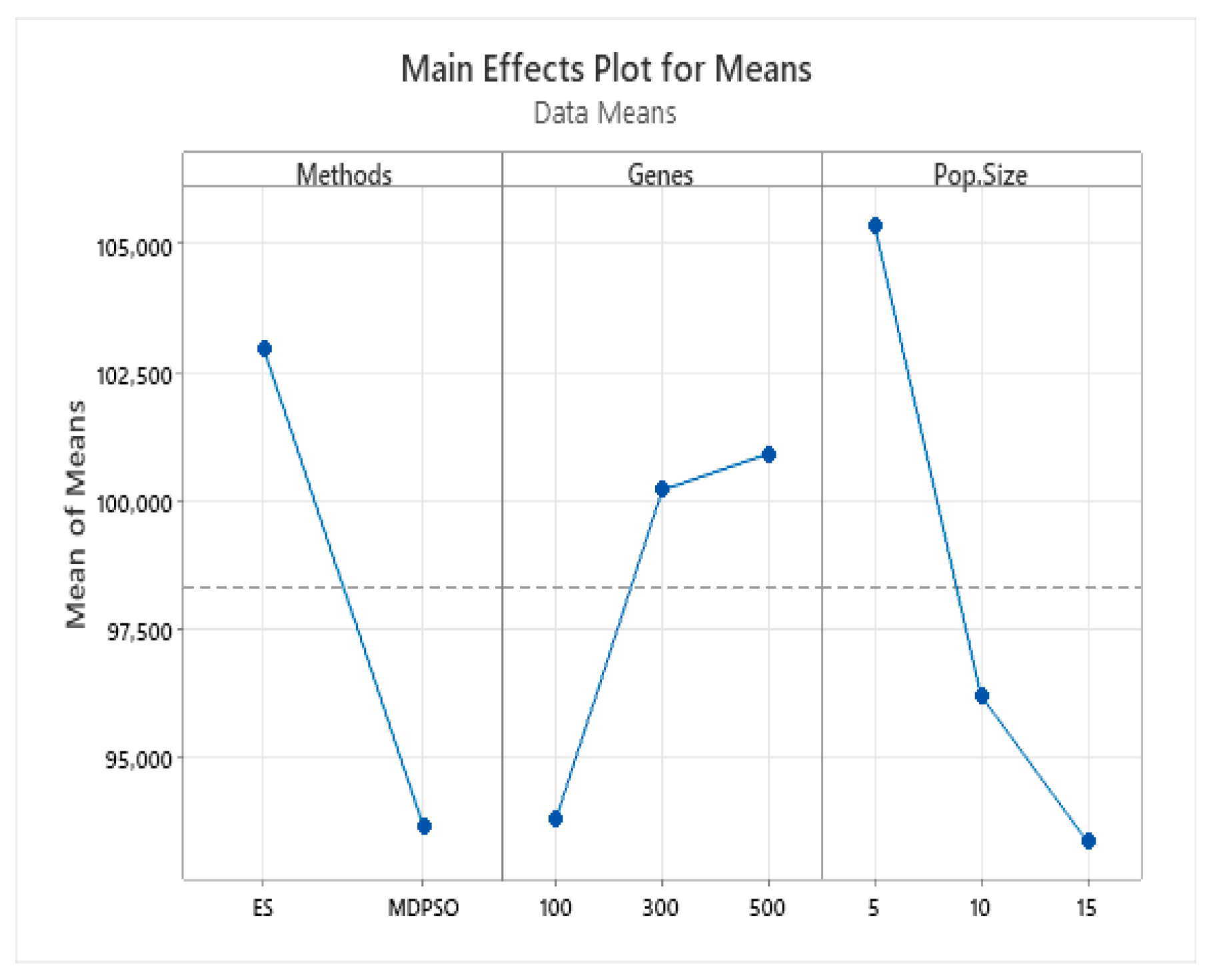

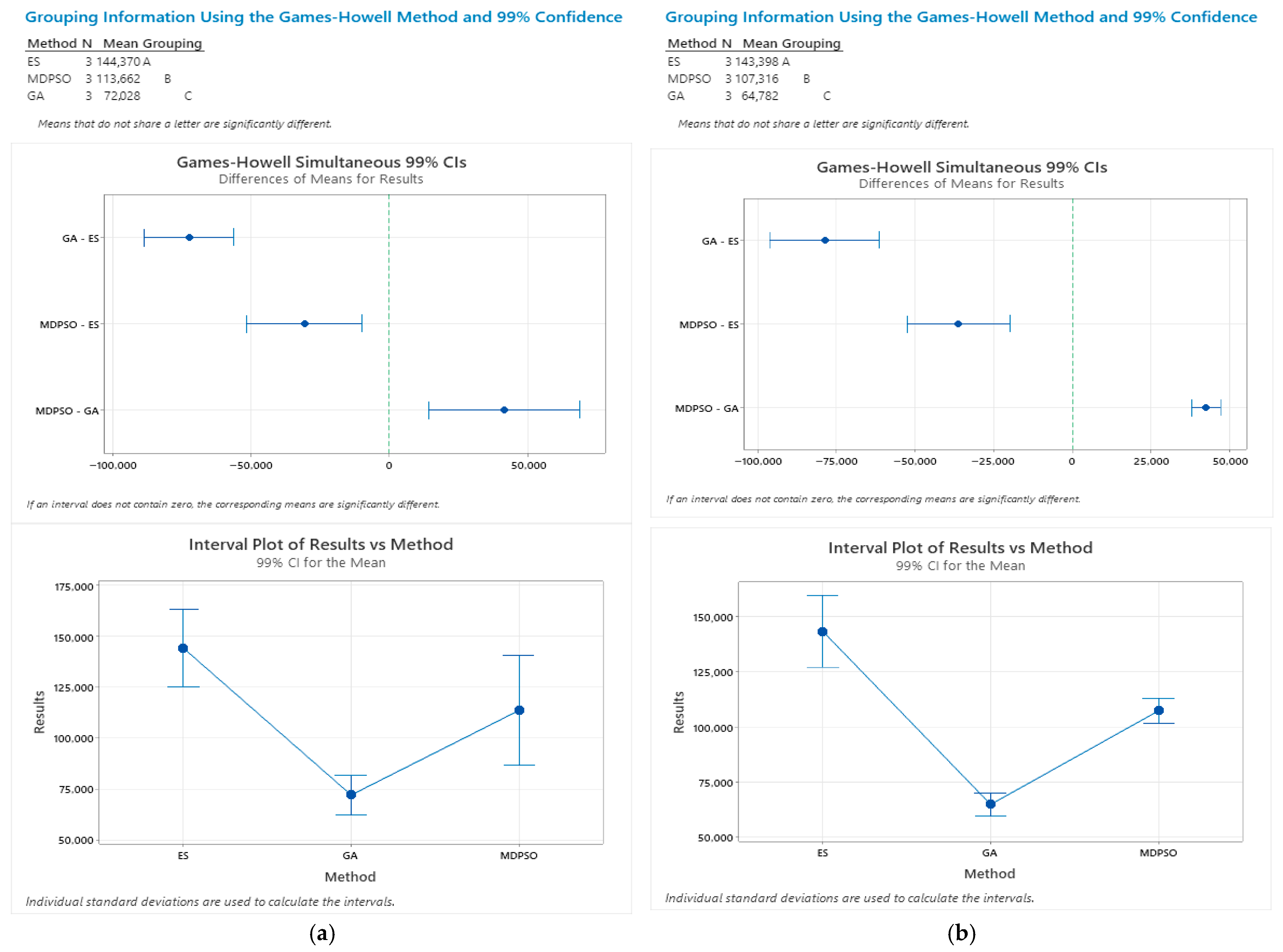

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Mathematical Model Results

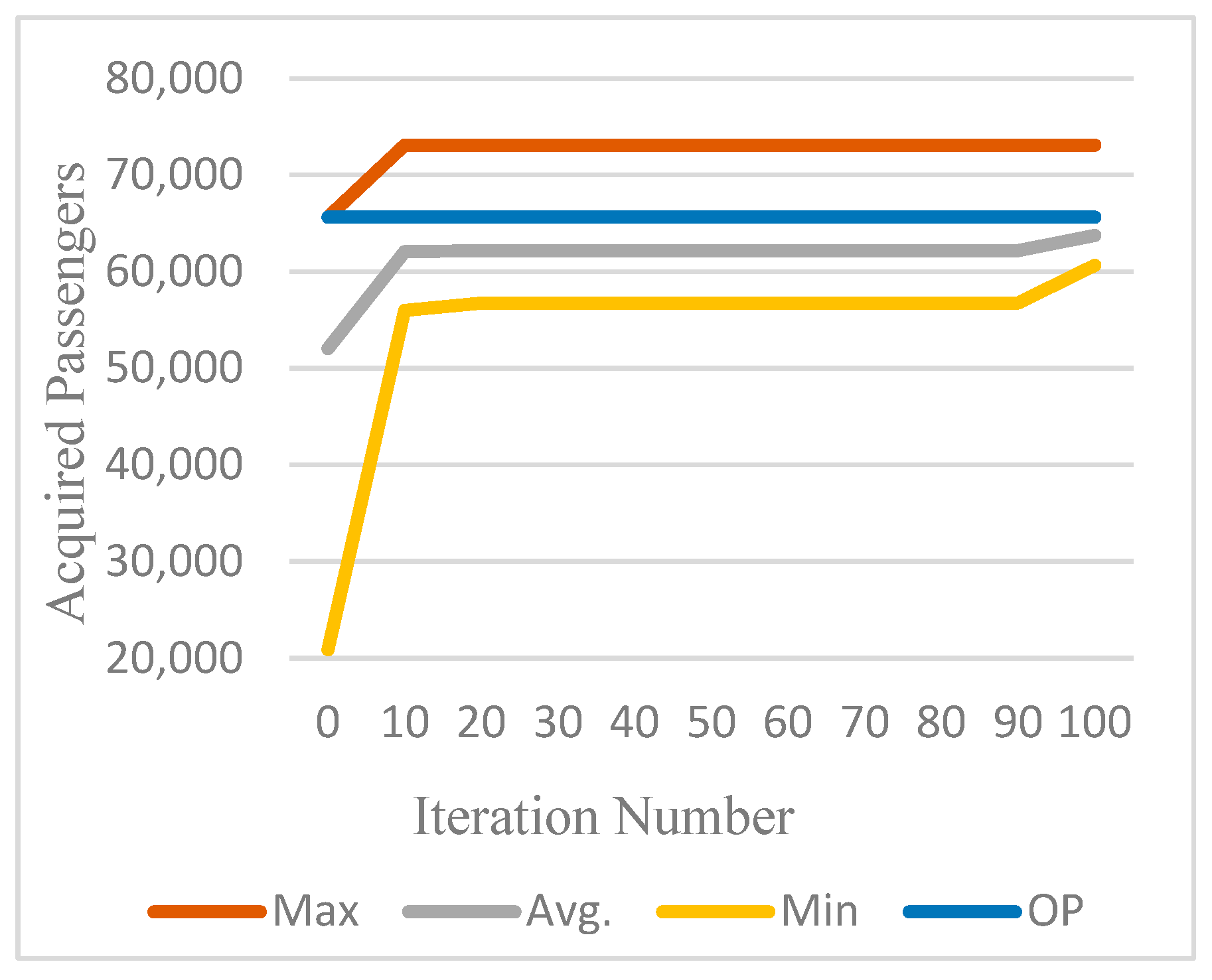

6.2. Genetic Algorithm Performance

6.3. Modified Discrete Particle Swarm Optimization Performance

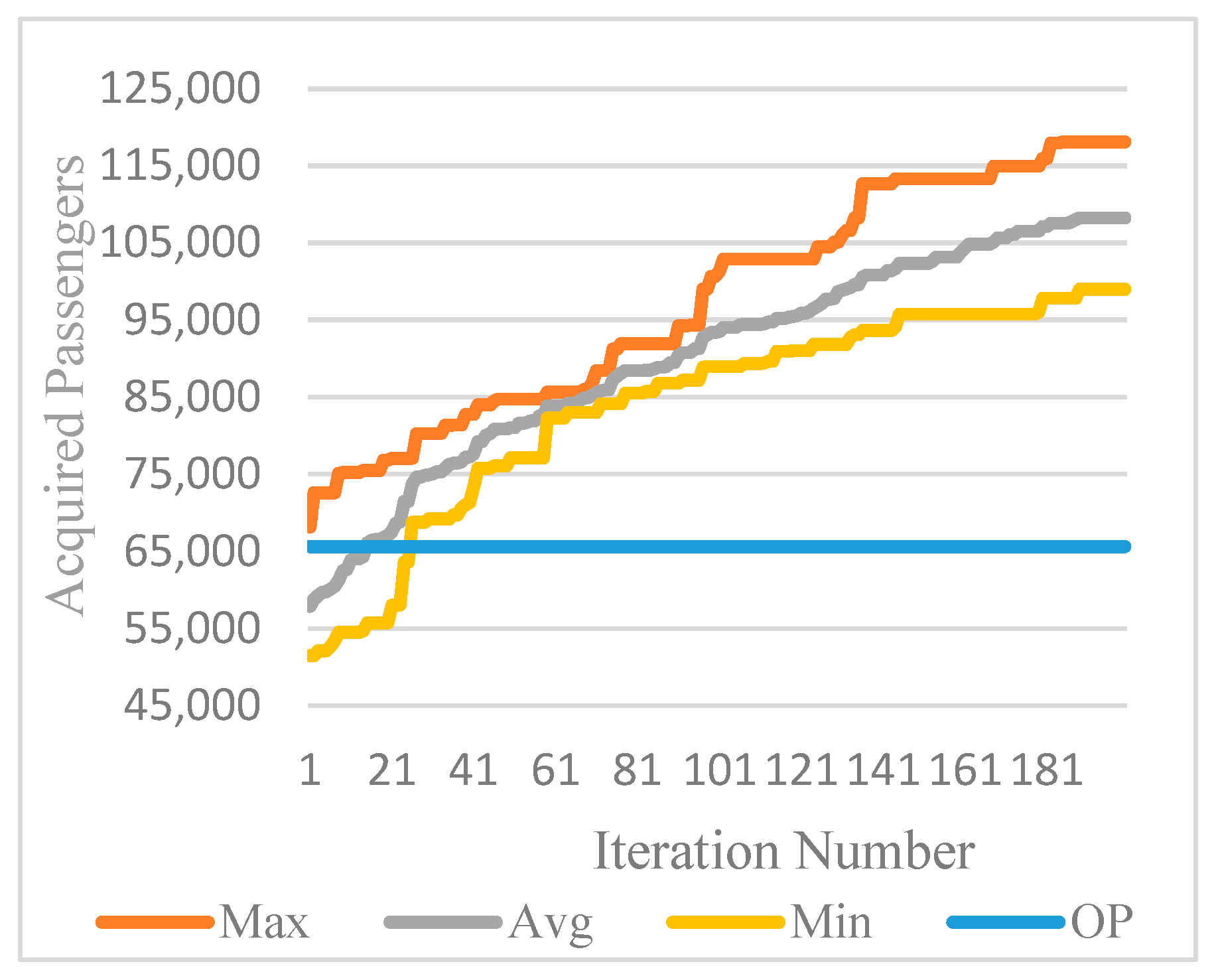

6.4. Evolutionary Strategy Performance

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The International Air Transport Association (IATA). June 2023 Global Outlook for Air Transport. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/global-outlook-for-air-transport----june-2023/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- The International Air Transport Association (IATA). Global Outlook for Air Transport June 2025. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/publications/economics/reports/global-outlook-for-air-transport-june-2025/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Wikipedia. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Civil_Aviation_Organization (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- The International Air Transport Association (IATA). 2019 End-Year-Report. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/airline-industry-economic-performance---december-2019---report/ (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- The International Air Transport Association (IATA). 2020 End-Year-Report. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/airline-industry-economic-performance---november-2020---report/ (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Ulaştırma ve Altyapı Bakanlığı. Ulaşan ve Erişen Türkiye 2022. Available online: https://www.uab.gov.tr/uploads/pages/bakanlik-yayinlari/ulasan-erisen-turkiye-171122.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Sivil Havacılık Genel Müdürlüğü. Faaliyet Raporu. Available online: https://web.shgm.gov.tr/documents/sivilhavacilik/files/kurumsal/faaliyet/2022.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Sivil Havacılık Genel Müdürlüğü. Faaliyet Raporu 2024. Available online: https://web.shgm.gov.tr/tr/kurumsal/4006-faaliyet-raporlarimiz (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Wikipedia. Tourism in Turkey. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tourism_in_Turkey (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Çiftçi, M.E.; Özkır, V. Optimising Flight Connection Times in Airline Bank Structure through Simulated Annealing and Tabu Search Algorithms. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 87, 101858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredyński, A.; Grosche, T.; Rothlauf, F. Impact of Timetable Synchronizatıon on Hub Connectivity of European Carriers. J. Air Transp. Stud. 2016, 7, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Delahaye, D.; Liang, M. Arrival and Departure Sequencing, Considering Runway Assignment Preferences and Crossings. Aerospace 2024, 11, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Y. Flight Arrival Scheduling via Large Language Model. Aerospace 2024, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Yang, S.; Wu, W.; Sun, B. A Multi-Objective Fuzzy Optimization Model for Multi-Type Aircraft Flight Scheduling Problem. Transport 2024, 39, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Delahaye, D.; O’Connell, J.F.; Le, M. Enhancing Airline Connectivity: An Optimisation Approach for Flight Scheduling in Multi-Hub Networks with Bank Structures. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 191, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhwani, R.; Jayaram, J.; Ivanov, D. Meeting Economic and Social Viability Goals in Regional Airline Schemes through Hub-and-Spoke Network Connectivity. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Dong, B.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, G.; Tan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Dai, H. Multiple-Allocation Hub-and-Spoke Network Design with Maximizing Airline Profit Utility in Air Transportation Network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 7294–7310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, J.; Boysen, N.; Briskorn, D. Optimizing Consolidation Processes in Hubs: The Hub-Arrival-Departure Problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 298, 1051–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, C.; Atkins, S.; Cook, L.; Lent, S.; Prevost, T. Ration by Schedule for Airport Arrival and Departure Planning and Scheduling. In Proceedings of the 2010 Integrated Communications, Navigation, and Surveillance Conference Proceedings, Herndon, VA, USA, 11–13 May 2010; IEEE: Herndon, VA, USA, 2010; pp. I3-1–I3-9. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, Z.; He, C. Stochastic Terminal Flight Arrival and Departure Scheduling Problem under Performance-Based Navigation Environment. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 119, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.; Lubig, D.; Asadi, E.; Rosenow, J.; Itoh, E.; Athota, S.; Duong, V.N. Implementation of a Long-Range Air Traffic Flow Management for the Asia-Pacific Region. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 124640–124659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungai, T.; Hongjun, X. Optimizing Arrival Flight Delay Scheduling Based on Simulated Annealing Algorithm. Phys. Procedia 2012, 33, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeichi, N. Nominal Flight Time Optimization for Arrival Time Scheduling through Estimation/Resolution of Delay Accumulation. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 77, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondoloni, S.; Rozen, N. Aircraft Trajectory Prediction and Synchronization for Air Traffic Management Applications. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2020, 119, 100640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, R.; Prats, X.; Polishchuk, T.; Polishchuk, V. Traffic Synchronization in Terminal Airspace to Enable Continuous Descent Operations in Trombone Sequencing and Merging Procedures: An Implementation Study for Frankfurt Airport. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 121, 102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zeng, W.; Quan, Z.; Tan, X. Domain Knowledge-Powered Attention for Air Traffic Management Hazardous Events Classification. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 138, 109454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, P.; Kamdar, V. A Modern Approach to Real-Time Air Traffic Management System. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.03652. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wandelt, S.; Sun, X. Airline Scheduling Optimization: Literature Review and a Discussion of Modelling Methodologies. Intell. Transp. Infrastruct. 2024, 3, liad026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıncılar, A.; Güner, E. A New Tool for Robust Aircraft Routing: Superior Robust Aircraft Routing (Sup-RAR). J. Air Transp. Manag. 2025, 124, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinam, S.; Wood, Z.; Sridhar, B.; Jung, Y. A Generalized Dynamic Programming Approach for a Departure Scheduling Problem. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 10–13 August 2009; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, K.K.H.; Lee, C.K.M.; Chan, F.T.S.; Qin, Y. Robust Aircraft Sequencing and Scheduling Problem with Arrival/Departure Delay Using the Min-Max Regret Approach. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 106, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, I.; Tolujevs, J. Optimization of Ground Vehicles Movement on the Aerodrome. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 24, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Chien, S.; Schonfeld, P.; Hu, D. Optimizing Flight Equencing and Gate Assignment Considering Terminal Configuration and Walking Time. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 86, 101816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedehzadeh, S.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Baboli, A.; Mohammadi, M. Optimization of a Multi-Modal Tree Hub Location Network with Transportation Energy Consumption: A Fuzzy Approach. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2015, 30, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.; Hua, S. Flight Time and Frequency-Optimization Model for Multiairport System Operation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Yang, Y.; Li, L. Integrated Optimization of Urban Agglomeration Passenger Transport Hub Location and Network Design. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazargan, M. Airline Operations and Scheduling, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-7546-7900-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Chuhang, Y.; Lau, H.Y.K.H. An Integrated Flight Scheduling and Fleet Assignment Method Based on a Discrete Choice Model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 98, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenan, N.; Jebali, A.; Diabat, A. An Integrated Flight Scheduling and Fleet Assignment Problem under Uncertainty. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 100, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Ren, Y.; Wei, W.; Yang, Z. A Data-Driven Flight Schedule Optimization Model Considering the Uncertainty of Operational Displacement. Comput. Oper. Res. 2021, 133, 105328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandamali, G.G.N.; Su, R.; Zhang, Y. Flight Routing and Scheduling Under Departure and En Route Speed Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, R.; Li, Q.; Cassandras, C.G.; Xie, L. Distributed Flight Routing and Scheduling for Air Traffic Flow Management. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 18, 2681–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, R.; Sandamali, G.G.N.; Zhang, Y.; Cassandras, C.G.; Xie, L. A Hierarchical Heuristic Approach for Solving Air Traffic Scheduling and Routing Problem with a Novel Air Traffic Model. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 3421–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, H.; Cao, K.; Zhou, J.; Wei, T.; Hu, S. Uncertainty-Aware Flight Scheduling for Airport Throughput and Flight Delay Optimization. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2020, 56, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambelho, M.; Mitici, M.; Pickup, S.; Marsden, A. Assessing Strategic Flight Schedules at an Airport Using Machine Learning-Based Flight Delay and Cancellation Predictions. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 82, 101737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchiani, V.; Salazar-González, J.-J. Heuristic Approaches for Flight Retiming in an Integrated Airline Scheduling Problem of a Regional Carrier. Omega 2020, 91, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, J.P.; Barnhart, C.; Antunes, A.P. Integrated Flight Scheduling and Fleet Assignment Under Airport Congestion. Transp. Sci. 2013, 47, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birolini, S.; Antunes, A.P.; Cattaneo, M.; Malighetti, P.; Paleari, S. Integrated Flight Scheduling and Fleet Assignment with Improved Supply-Demand Interactions. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2021, 149, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Song, H.; Zhu, W. Low-Carbon Airline Fleet Assignment: A Compromise Approach. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 68, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dožić, S.; Jelović, A.; Kalić, M.; Čangalović, M. Variable Neighborhood Search to Solve an Airline Fleet Sizing and Fleet Assignment Problem. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 37, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Vaze, V.; Jacquillat, A. Airline Timetable Development and Fleet Assignment Incorporating Passenger Choice. Transp. Sci. 2019, 54, trsc.2019.0924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Nie, L.; Liebchen, C.; Yuan, W.; Wu, X. Improving Synchronization in an Air and High-Speed Rail Integration Service via Adjusting a Rail Timetable: A Real-World Case Study in China. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Mi, X.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Ke, Y.; Wang, Y. Improving Synchronization in High-Speed Railway and Air Intermodality: Integrated Train Timetable Rescheduling and Passenger Flow Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 2651–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, S.; An, W.; Hu, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. Demand-Driven Train Timetabling for Air and Intercity High-Speed Rail Synchronization Service. Transp. Lett. 2023, 15, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Niu, H. A Dynamic Programming Approach to Synchronize Train Timetables. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 168781401771236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Sun, H.; Yang, X.; Jin, J.G.; Wang, D.Z.W. Scheduling Synchronization in Urban Rail Transit Networks: Trade-Offs between Transfer Passenger and Last Train Operation. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2020, 138, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Rojas, O.J.; Muñoz, J.C. Synchronizing Different Transit Lines at Common Stops Considering Travel Time Variability along the Day. Transp. Transp. Sci. 2016, 12, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, X. Autonomous Bus Timetable Synchronization for Maximizing Smooth Transfers with Passenger Assignment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 193, 116430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwind, T. Route Feasibility Testing and Forward Time Slack for the Synchronized Pickup and Delivery Problem. OR Spectr. 2019, 41, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen, D.; Morrison, W.G. Regulation, Competition and Network Evolution in Aviation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2005, 11, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Yoo, K.E.; Park, Y. A Continuous Connectivity Model for Evaluation of Hub-and-Spoke Operations. Transp. Transp. Sci. 2014, 10, 894–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghouwt, G.; Redondi, R. Connectivity in Air Transport Networks: An Assessment of Models and Applications. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 2013, 47, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld, P.; Brons, M. Quality of Hub-and-Spoke Networks; the Effects of Timetable Co-Ordination on Waiting Time and Rescheduling Time. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2001, 7, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesi, A. Measuring Airline Hub Timetable Co-Ordination and Connectivity: Definition of a New Index and Application to a Sample of European Hubs. Eur. Transp. 2006, 34, 54–74. [Google Scholar]

- Paleari, S.; Redondi, R.; Malighetti, P. A Comparative Study of Airport Connectivity in China, Europe and US: Which Network Provides the Best Service to Passengers? Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2010, 46, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, H.I.; Phanden, R.K. Due-Date Agreement in Integrated Process Planning and Scheduling Environment Using Common Meta-Heuristics. In Integration of Process Planning and Scheduling: Approaches and Algorithms; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, S. Essentials of Metaheuristics: A Set of Undergraduate Lecture Notes, 2nd ed.; Online Version 2.0; Lulu Press: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan, B.; Johnson, E.L. Airline Crew Scheduling: State-of-the-Art. Ann. Oper. Res. 2005, 140, 305–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. Istanbul Airport. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Istanbul_Airport (accessed on 9 August 2022).

| Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 e | 2025 f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segment Passengers, million | 4.560 | 1.779 | 2.304 | 3.452 | 4.426 | 4.779 | 4.988 |

| Passenger Revenue, $bn | 607 | 189 | 242 | 437 | 648 | 682 | 693 |

| Cargo Revenue, $bn | 101 | 140 | 210 | 206 | 139 | 149 | 142 |

| Ancillary and Other Revenue, $bn | 130 | 55 | 61 | 95 | 122 | 135 | 144 |

| Net Profit, $bn | 26.4 | −137.7 | −40.4 | −3.5 | 37.3 | 32.4 | 36.0 |

| Aircraft departures, million | 37.5 | 19.7 | 24.2 | 29.5 | 35.5 | 37.4 | 38.3 |

| Unique city pairs | 20.886 | 16.218 | 16.259 | 20.424 | 21.736 | >22.000 | N/A |

| 2003 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2024/2003 % Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger Traffic | Domestic | 9,147,439 | 78,670,030 | 90,390,766 | 95,293,038 | %941.7 |

| International | 25,296,216 | 103,277,976 | 123,302,397 | 134,694,726 | %432.5 | |

| Transfer | 0 | 385,838 | 443,412 | 236,847 | - | |

| Total | 34,443,655 | 182,333,844 | 214,136,575 | 230,224,611 | %568.4 | |

| Airplane Traffic | Domestic | 156,582 | 789,257 | 869,404 | 902,078 | %476.1 |

| International | 218,405 | 699,040 | 816,473 | 816,473 | %273.8 | |

| Transfer | 154,218 | 394,889 | 485,453 | 521,724 | %238.3 | |

| Total | 529,205 | 1,883,186 | 2,171,330 | 2,240,275 | %323.3 | |

| Airplane Fleet Size | 162 | 598 | 668 | 729 | %350 | |

| Waiting Time (h) | Waiting Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| 0–1 | 0 |

| 1–3 | 100 |

| 3–5 | 50 |

| 5–7 | 20 |

| 7–10 | 10 |

| 10+ | 0 |

| From | To | Average (Passengers) |

|---|---|---|

| A | X | 15 |

| A | Y | 20 |

| A | Z | 25 |

| … | … | … |

| Z | A | 20 |

| Z | B | 15 |

| Z | C | 10 |

| Point | Arrival in Hub-Airport | Departure from Hub-Airport |

|---|---|---|

| A | Monday (06:05), Sat (12:20) | Mon (12:20) |

| B | Tue (12:10), Sat (14:15) | Tue (16:00) |

| C | Wed (12:25), Thu (18:30) | Thu (22:25), Fri (17:45) |

| … | … | … |

| X | Fri (21:50), Sat (13:15) | Sun (12:15) |

| Y | Mon (11:05) | Mon (13:10), Fri (17:55) |

| Z | Fri (22:05) | Tue (12:35), Sat (01:20) |

| Arrival in Hub-Airport (X-Axis) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day (Y-Axis) | Hour (Y-Axis) | 1 | 2 | … | a |

| Monday | 00:00 | … | |||

| Monday | 00:05 | ||||

| Monday | 00:10 | ||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Sunday | 23:45 | ||||

| Sunday | 23:50 | ||||

| Sunday | 23:55 | … | |||

| Departure from Hub-Airport (X-Axis) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day (Y-Axis) | Hour (Y-Axis) | 1 | 2 | … | d |

| Monday | 00:00 | ||||

| Monday | 00:05 | ||||

| Monday | 00:10 | ||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Sunday | 23:45 | ||||

| Sunday | 23:50 | ||||

| Sunday | 23:55 | … | |||

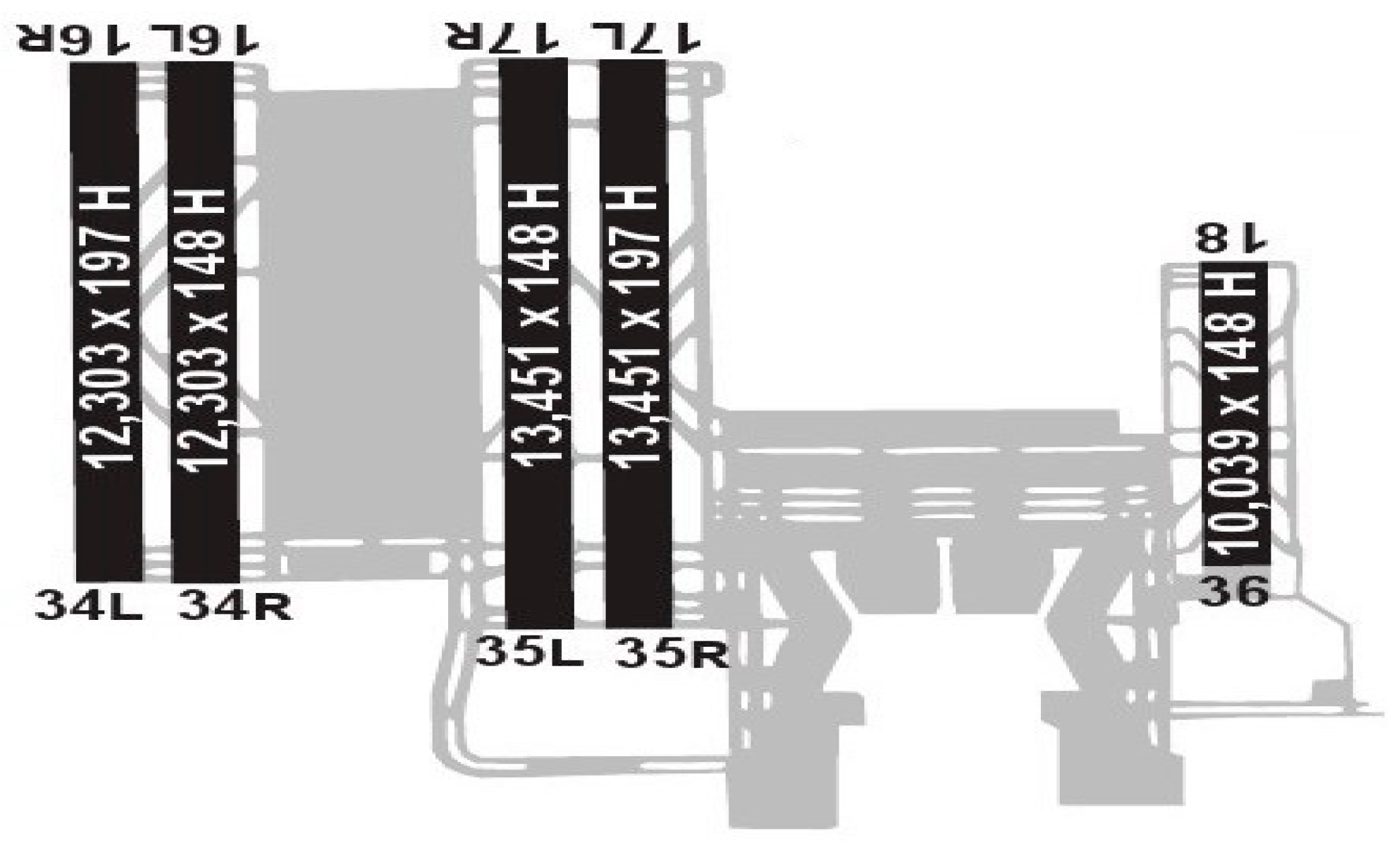

| Stages | Terminal (m2) | Annual Passenger Capacity (Million) | Runways |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Stage | 1,440,000 | 90 | 5 |

| Second stage | 2 | ||

| Third Stage | 960,000 | 60 | |

| Fourth stage * | 800,000 | 50 | 1 |

| Total | 3,200,000 | 200 | 8 |

| Runways | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Length (m) | Width (m) | Surface |

| 16L/34R | 3750 | 45 | Asphalt |

| 16R/34L | 3750 | 60 | Asphalt |

| 17L/35R | 4100 | 60 | Asphalt |

| 17R/35L | 4100 | 45 | Asphalt |

| 18/36 | 3060 * | 45 | A&C ** |

| 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. | 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. | 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. | 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. | 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORD | IAD | 19 | IAD | ORD | 11 | LAX | ORD | 17 | JFK | ORD | 7 | YYZ | ORD | 23 |

| ORD | LAX | 19 | IAD | LAX | 17 | LAX | IAD | 15 | JFK | IAD | 9 | YYZ | IAD | 15 |

| ORD | JFK | 11 | IAD | JFK | 19 | LAX | JFK | 5 | JFK | LAX | 11 | YYZ | LAX | 9 |

| ORD | YYZ | 27 | IAD | YYZ | 15 | LAX | YYZ | 4 | JFK | YYZ | 15 | YYZ | JFK | 10 |

| Flight Point | Departure Flight Time | Arrival Flight Time |

|---|---|---|

| ORD | 5–10 min | 10–15 min |

| IAD | 10–15 min | 5–10 min |

| LAX | 10–15 min | 5–10 min |

| JFK | 15–20 min | 0–5 min |

| YYZ | 15–20 min | 0–5 min |

| 0–5 min | 5–10 min | 10–15 min | 15–20 min | 20–25 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Departure Flights | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Arrival Flights | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. | A.P. | 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. | A.P. | 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. | A.P. | 1. Point | 2. Point | Dem. | A.P. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORD | IAD | 19 | 0.0 | IAD | LAX | 17 | 17.0 | LAX | JFK | 5 | 2.5 | JFK | YYZ | 15 | 3 |

| ORD | LAX | 19 | 0.0 | IAD | JFK | 19 | 9.5 | LAX | YYZ | 4 | 2.0 | YYZ | ORD | 23 | 23 |

| ORD | JFK | 11 | 11.0 | IAD | YYZ | 15 | 7.5 | JFK | ORD | 7 | 7.0 | YYZ | IAD | 15 | 7.5 |

| ORD | YYZ | 27 | 27.0 | LAX | ORD | 17 | 0.0 | JFK | IAD | 9 | 4.5 | YYZ | LAX | 9 | 4.5 |

| IAD | ORD | 11 | 0.0 | LAX | IAD | 15 | 15.0 | JFK | LAX | 11 | 5.5 | YYZ | JFK | 10 | 2 |

| GA Variant | Average of Best Values | Average of Avg. Values | Average of Worst Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-Point Crossover | 75,693 | 63,619 | 57,620 |

| Two-Point Crossover | 69,270 | 62,956 | 56,907 |

| Three-Point Crossover | 79,372 | 64,632 | 57,394 |

| Iter # | Seed1-Best | Seed1-Avg. | Seed2-Best | Seed2-Avg. | Seed3-Best | Seed3-Avg. | Seed4-Best | Seed4-Avg. | Seed5-Best | Seed5-Avg. | OP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 72,367 | 55,994 | 67,171 | 53,956 | 68,460 | 50,387 | 67,911 | 53,268 | 68,335 | 56,547 | 65,659 |

| 30 | 72,372 | 65,871 | 67,173 | 62,490 | 71,314 | 62,363 | 117,105 | 70,920 | 68,901 | 61,520 | |

| 50 | 72,372 | 65,871 | 67,173 | 62,490 | 71,314 | 62,363 | 117,105 | 70,920 | 68,901 | 61,520 |

| ES | MDPSO | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Chromosomes | ||||||

| Genes | 5 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| 100 | 107,297 | 96,947 | 89,846 | 101,042 | 84,549 | 83,255 |

| 300 | 110,980 * | 105,366 | 10,1233 | 104,783 ** | 88,052 | 90,838 |

| 500 | 108,484 | 106,672 | 99,814 | 99,688 | 95,661 | 95,167 |

| Iter # | Seed1-Best | Seed1-Avg. | Seed1-Worst | Seed2-Best | Seed2-Avg. | Seed-Worst | Seed3-Best | Seed3-Avg. | Seed3-Worst | OP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 73,107 | 62,157 | 56,737 | 72,888 | 65,267 | 61,740 | 70,089 | 65,327 | 60,224 | 65,659 |

| 40 | 73,107 | 62,157 | 56,737 | 72,888 | 65,267 | 61,740 | 70,089 | 65,327 | 60,224 | |

| 60 | 73,107 | 62,157 | 56,737 | 72,888 | 65,267 | 61,740 | 70,089 | 65,327 | 60,224 | |

| 80 | 73,107 | 62,157 | 56,737 | 72,888 | 65,267 | 61,740 | 70,089 | 65,327 | 60,224 | |

| 100 | 73,107 * | 63,753 | 60,675 | 72,888 | 65,267 | 61,740 | 70,089 | 65,327 | 60,224 |

| Iter # | Seed-1 Best | Seed-1 Average | Seed-1 Worst | Seed-2 Best | Seed-2 Average | Seed-2 Worst | Seed-3 Best | Seed-3 Average | Seed-3 Worst | OP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 78,447 | 73,642 | 65,807 | 82,320 | 77,192 | 72,048 | 82,737 | 77,259 | 71,337 | 65,659 |

| 80 | 86,775 | 82,951 | 77,927 | 93,934 | 86,229 | 82,559 | 91,915 | 88,417 | 85,514 | |

| 120 | 96,136 | 92,593 | 86,558 | 97,902 | 93,266 | 87,661 | 102,883 | 95,566 | 91,024 | |

| 160 | 108,931 | 102,020 | 92,473 | 104,362 | 99,758 | 93,012 | 113,322 | 103,803 | 95,758 | |

| 200 | 114,197 | 106,247 | 100,593 | 108,696 | 107,466 | 106,248 | 118,092 * | 108,236 | 98,987 |

| Iter # | Seed-1 Best | Seed-1 Average | Seed-1 Worst | Seed-2 Best | Seed-2 Average | Seed-2 Worst | Seed-3 Best | Seed-3 Average | Seed-3 Worst | OP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 99,987 | 99,278 | 98,532 | 105,508 | 102,960 | 101,172 | 88,481 | 881,72 | 87,918 | 65,659 |

| 80 | 11,4001 | 112,652 | 111,796 | 123,808 | 123,504 | 123,250 | 106,834 | 106,341 | 10,5803 | |

| 120 | 126,137 | 125,615 | 125,307 | 136,197 | 133,189 | 131,507 | 122,682 | 121,497 | 120,952 | |

| 160 | 136,914 | 135,424 | 134,682 | 143,861 | 141,830 | 141,113 | 131,967 | 130,291 | 129,783 | |

| 200 | 144,520 | 143,785 | 143,463 | 147,596 * | 146,019 | 145,281 | 140,993 | 140,389 | 139,991 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Demir, H.I.; Dervis, S. Enhancing Flight Connectivity via Synchronization of Arrivals and Departures in Hub Airports with Evolutionary and Swarm-Based Metaheuristics. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010006

Demir HI, Dervis S. Enhancing Flight Connectivity via Synchronization of Arrivals and Departures in Hub Airports with Evolutionary and Swarm-Based Metaheuristics. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemir, Halil Ibrahim, and Suraka Dervis. 2026. "Enhancing Flight Connectivity via Synchronization of Arrivals and Departures in Hub Airports with Evolutionary and Swarm-Based Metaheuristics" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010006

APA StyleDemir, H. I., & Dervis, S. (2026). Enhancing Flight Connectivity via Synchronization of Arrivals and Departures in Hub Airports with Evolutionary and Swarm-Based Metaheuristics. Biomimetics, 11(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010006