Mechanical Characterization of Stick Insect Tarsal Attachment Fluid Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Abstract

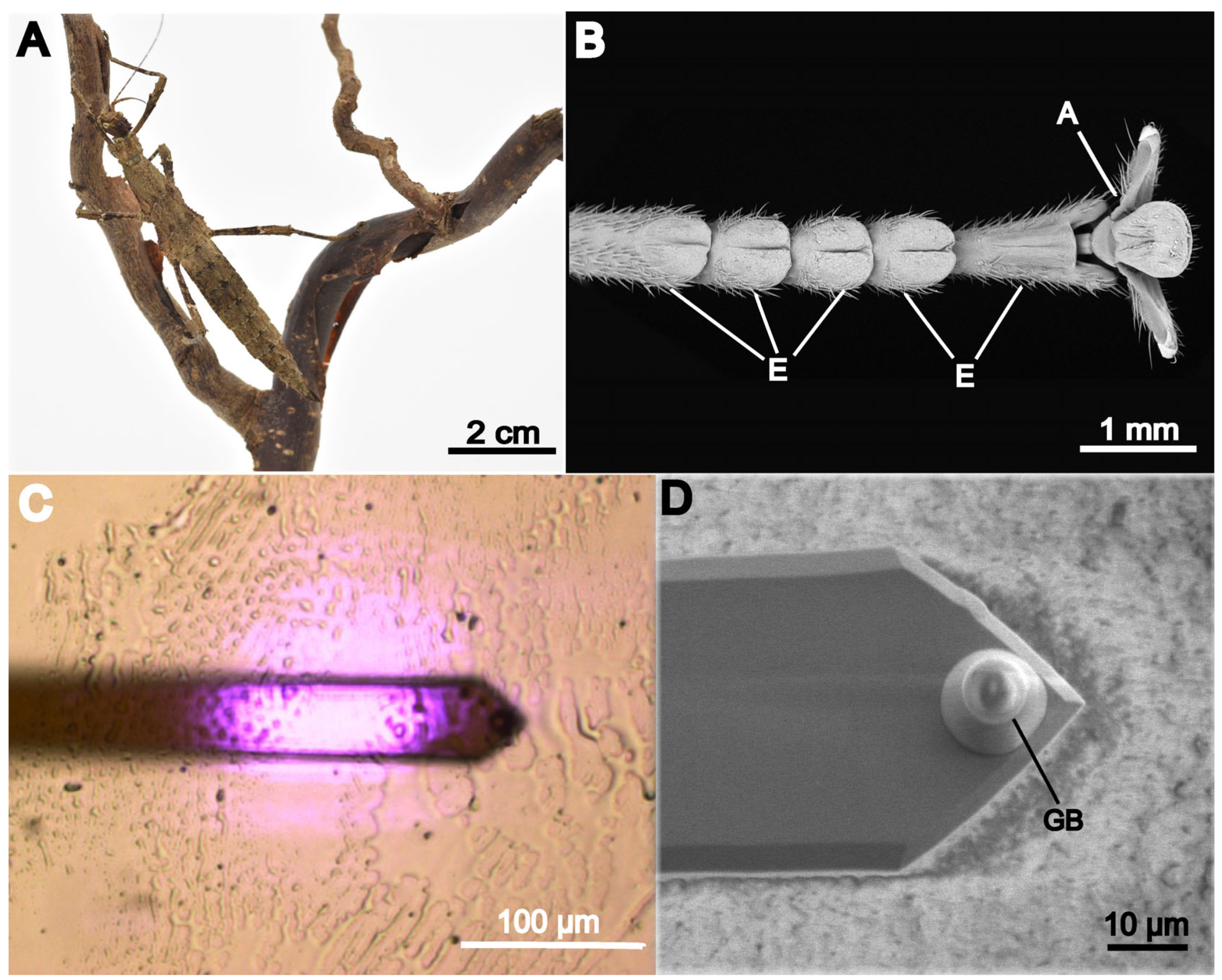

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Footprint Acquisition

2.2. White Light Interferometry

2.3. Cantilever Preparation

2.4. Force Measurements

2.5. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Changes over Time

3.2. Droplet Dimensions

3.3. Force Measurements of Different Droplets

3.4. Physical Properties of Droplets

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Viscoelastic Properties

4.1.1. General Challenges of AFM Nanoindentation

4.1.2. Evaluation of the Results Using Different Contact Models

4.1.3. Influence of Droplet Size and Cantilever

4.2. Characterization of Droplet Types

4.2.1. “Almost-Inviscid” Droplets

4.2.2. “Viscous” Droplets

4.2.3. Time Dependence of Elastic Modulus and Viscosity

4.2.4. “Rigid” Droplets

4.2.5. Variation in Secretion Amount

4.2.6. Possible Ecological Functions of the Fluid Complexity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grimaldi, D.; Engel, M.S. Evolution of the Insects, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Creton, C.; Gorb, S.N. Sticky feet: From animals to materials. MRS Bull. 2007, 32, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, R.G.; Gorb, S.N. Ultrastructure of attachment specializations of hexapods (Arthropoda): Evolutionary patterns inferred from a revised ordinal phylogeny. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2001, 39, 177–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, T.H.; Gorb, S.N. Physical constraints lead to parallel evolution of micro- and nanostructures of animal adhesive pads: A review. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2021, 12, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, T.H.; Gorb, S.N. Convergent evolution of animal adhesive pads. In Convergent Evolution. Fascinating Life Sciences, 1st ed.; Bels, V.L., Russell, A.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 257–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gorb, S.N.; Heepe, L. Biological fibrillar adhesives: Functional principles and biomimetic applications. In Handbook of Adhesion Technology, 1st ed.; da Silva, L.F.M., Öchsner, A., Adams, R.D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bennemann, M.; Backhaus, S.; Scholz, I.; Park, D.; Mayer, J.; Baumgartner, W. Determination of the Young’s modulus of the epicuticle of the smooth adhesive organs of Carausius morosus using tensile testing. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 3677–3687. [Google Scholar]

- Gorb, S.N.; Jiao, Y.; Scherge, M. Ultrastructural architecture and mechanical properties of attachment pads in Tettigonia viridissima (Orthoptera Tettigoniidae). J. Comp. Physiol. A 2000, 186, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, J.H. Physical principles of fluid-mediated insect attachment—shouldn’t insects slip? Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, P.; Federle, W. Biomechanics of smooth adhesive pads in insects: Influence of tarsal secretion on attachment performance. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2006, 192, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, A.E.; Filippov, A.E.; Gorb, S.N. Insect wet steps: Loss of fluid from insect feet adhering to a substrate. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20120639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonte, D.; Federle, W. Rate-dependence of ‘wet’ biological adhesives and the function of the pad secretion in insects. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou, B.; Gay, C.; Laurent, B.; Cardoso, O.; Voigt, D.; Peisker, H.; Gorb, S.N. Extensive collection of femtoliter pad secretion droplets in beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata allows nanoliter microrheology. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peisker, H.; Heepe, L.; Kovalev, A.E.; Gorb, S.N. Comparative study of the fluid viscosity in tarsal hairy attachment systems of flies and beetles. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peisker, H.; Gorb, S.N. Evaporation dynamics of tarsal liquid footprints in flies (Calliphora vicina) and beetles (Coccinella septempunctata). J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 215, 1266–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, C.J.; Federle, W. Mechanisms of self-cleaning in fluid-based smooth adhesive pads of insects. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2012, 7, 046001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Gorb, S.N.; Büscher, T.H. Influence of surface free energy of the substrate and flooded water on the attachment performance of stick insects (Phasmatodea) with different adhesive surface microstructures. J. Exp. Biol. 2023, 226, jeb244295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vötsch, W.; Nicholson, G.; Müller, R.; Stierhof, Y.-D.; Gorb, S.N.; Schwarz, U. Chemical composition of the attachment pad secretion of the locust Locusta migratoria. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 32, 1605–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, U. Hydrocarbons in tarsal glands of Bombus terrestris. Experientia 1990, 46, 1080–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attygalle, A.B.; Aneshansley, D.J.; Meinwald, J.; Eisner, T. Defense by foot adhesion in a chrysomelid beetle (Hemisphaerota cyanea): Characterization of the adhesive oil. Zoology 2000, 103, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Speidel, M.W.; Kleemeier, M.; Hartwig, A.; Rischka, K.; Ellermann, A.; Daniels, R.; Betz, O. Structural and tribometric characterization of biomimetically inspired synthetic “insect adhesives”. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.E.; Gorb, S.N.; Baio, J.E. Multi-technique investigation of a biomimetic insect tarsal adhesive fluid. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021, 7, 681120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, B.N.J. On the mechanism of adhesion in biological systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 7614–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, A.M.; Dirks, J.H.; Henriques, S.; Federle, W. Arachnids secrete a fluid over their adhesive pads. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimaki, D.-M.; Andrew, C.N.S.; Attipoe, A.E.L.; Labonte, D. The physical properties of the stick insect pad secretion are independent of body size. J. R. Soc. Interface 2022, 19, 20220212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Gorb, S.N.; Büscher, T.H. Characterisation of morphologically distinct components in the adhesive secretion of Medauroidea extradentata (Phasmatodea) using cryo—Scanning electron microscopy. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, M.; Gorb, S.N.; Büscher, T.H. The effect of age on the attachment ability of stick insects (Phasmatodea). Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2024, 15, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugis, D. Adhesion of spheres: The JKR-DMT transition using a Dugdale model. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1992, 150, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyen, M.L. Nanoindentation of hydrated materials and tissues. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2015, 19, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zhao, H. Nanoindentation of soft biological materials. Micromachines 2018, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, J.I.; Revenko, I.; Rodriguez, B.J. Nanomechanics of cells and biomaterials studied by atomic force microscopy. Adv. Health Mater. 2015, 4, 2456–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, S.; Sindt, S.; Selhuber-Unkel, C. Automated analysis of soft hydrogel microindentation: Impact of various indentation parameters on the measurement of Young’s modulus. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, J.H.; Clemente, C.J.; Federle, W. Insect tricks: Two-phasic foot pad secretion prevents slipping. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganser, C.; Kreiml, P.; Morak, R.; Weber, F.; Paris, O.; Schennach, R.; Teichert, C. The effects of water uptake on mechanical properties of viscose fibers. Cellulose 2015, 22, 2777–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimaraes, C.F.; Gasperini, L.; Marques, A.P.; Reis, R.L. The stiffness of living tissues and its implications for their engineering. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, E.K.; Horkay, F.; Maresca, J.; Kachar, B.; Chadwick, R.S. Determination of elastic moduli of thin layers of soft material using the atomic force microscope. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 2798–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwiche, A.; Ingremeau, F.; Amarouchene, Y.; Maali, A.; Dufour, I.; Kellay, H. Rheology of polymer solutions using colloidal-probe atomic force microscopy. Phys. Rev. E. 2013, 87, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwyn, P.P.; Peressadko, A.; Schwarz, H.; Kastner, V.; Gorb, S.N. Material structure, stiffness, and adhesion: Why attachment pads of the grasshopper (Tettigonia viridissima) adhere more strongly than those of the locust (Locusta migratoria) (Insecta: Orthoptera). J. Comp. Physiol. A 2006, 192, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Kovalev, A.; Büscher, T.H.; Gorb, S.N. Comparative analysis of mechanical properties of arolium and euplantulae in Medauroidea extradentata (Phasmatodea), using in vivo atomic force microscopy, supports functional specialization of both types of attachment pads. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, e00616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Xia, X.; Scriven, L.E.; Gerberich, W.W. Spherical-tip indentation of viscoelastic material. Mech. Mater. 2005, 37, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federle, W.; Riehle, M.; Curtis, A.S.G.; Full, R.J. An integrative study of insect adhesion: Mechanics and wet adhesion of pretarsal pads in ants. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2002, 42, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, D.K.; Wendt, R.C. Estimation of the surface free energy of polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenfuss, I. The adhesive devices in larvae of Lepidoptera (Insecta, Pterygota). Zoomorphology 1999, 119, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.-J.; Baney, J.M. Contact mechanics and adhesion of viscoelastic spheres. Langmuir 1998, 14, 6570–6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malotky, D.L.; Chaundhurry, M.K. Investigation of capillary forces using atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 2001, 17, 7823–7829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crassous, J.; Ciccotti, M.; Charlaix, E. Capillary force between wetted nanometric contacts and its application to atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 2011, 27, 3468–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Robbins, M.O. Capillary adhesion at the nanometer scale. Phys. Rev. E 2014, 89, 062402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rianna, C.; Radmacher, M. Comparison of viscoelastic properties of cancer and normal thyroid cells on different stiffness substrates. Eur. Biophys. J. 2017, 46, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simic, R.; Mathis, C.H.; Spencer, N.D. A two-step method for rate-dependent nano-indentation of hydrogels. Polymer 2018, 137, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, C.H.; Simic, R.; Kang, C.; Ramakrishna, S.N.; Isa, L.; Spencer, N.D. Indenting polymer brushes of varying grafting density in a viscous fluid: A gradient approach to understanding fluid confinement. Polymer 2019, 169, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; Homburg, S.V.; Ehrmann, A. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) on biopolymers and hydrogels for biotechnological applications—Possibilities and limits. Polymers 2022, 14, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plazek, D.J. Temperature dependence of the viscoelastic behavior of Polystyrene. J. Phys. Chem. 1965, 69, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, J.D.; Miller, G.J.; Morgan, E.F.; Klapperich, C.M. Time-dependent mechanical characterization of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) hydrogels using nanoindentation and unconfined compression. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 23, 1472–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, H.S.; Reese, E.T. Enzymatic hydrolysis of soluble cellulose derivatives as measured by changes in viscosity. J. Gen. Physiol. 1950, 33, 601–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, O.; Maurer, A.; Verheyden, A.N.; Schmitt, C.; Kowalik, T.; Braun, J.; Grunwald, I.; Hartwig, A.; Neuenfeldt, M. First protein and peptide characterization of the tarsal adhesive secretions in the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria, and the Madagascar hissing cockroach, Gromphadorhina portentosa. Insect Mol. Biol. 2016, 25, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, H.; Betz, O.; Albert, K.; Lämmerhofer, M. Insect adhesion secretions: Similarities and dissimilarities in hydrocarbon profiles of tarsi and corresponding tibiae. J. Chem. Ecol. 2016, 42, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burack, J.; Gorb, S.N.; Büscher, T.H. Attachment performance of stick insects (Phasmatodea) on plant leaves with different surface characteristics. Insects 2022, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, T.H.; Buckley, T.R.; Grohmann, C.; Gorb, S.N.; Bradler, S. The Evolution of tarsal adhesive microstructures in stick and leaf insects (Phasmatodea). Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bußhardt, P.; Wolf, H.; Gorb, S.N. Adhesive and frictional properties of tarsal attachment pads in two species of stick insects (Phasmatodea) with smooth and nubby euplantulae. Zoology 2012, 115, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labonte, D.; Williams, J.A.; Federle, W. Surface contact and design of fibrillar friction pads in stick insects (Carausius morosus): Mechanisms for large friction coefficients and negligible adhesion. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, T.H.; Kryuchkov, M.; Katanaev, V.L.; Gorb, S.N. Versatility of turing patterns potentiates rapid evolution in tarsal attachment microstructures of stick and leaf insects (Phasmatodea). J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20180281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, O. Adhesive exocrine glands in insects: Morphology, ultrastructure, and adhesive secretion. In Biological Adhesive Systems, 1st ed.; von Byern, J., Grunwald, I., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 111–152. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, C.J.; Bullock, J.M.R.; Beale, A.; Federle, W. Evidence for self-cleaning in fluid-based smooth and hairy adhesive systems of insects. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirks, J.H. Adhesion in insects. In Encyclopedia of Nanotechnology, 1st ed.; Bhushan, B., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Betz, O.; Frenzel, M.; Steiner, M.; Vogt, M.; Kleemeier, M.; Hartwig, M.; Sampalla, B.; Rupp, F.; Boley, M.; Schmitt, C. Adhesion and friction of the smooth attachment system of the cockroach Gromphadorhina portentosa and the influence of the application of fluid adhesives. Biol. Open. 2017, 6, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büscher, T.H.; Gorb, S.N. Complementary effect of attachment devices in stick insects (Phasmatodea). J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb209833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, T.H.; Becker, M.; Gorb, S.N. Attachment performance of stick insects (Phasmatodea) on convex substrates. J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 223, jeb226514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Steinhart, M.; Gorb, S.N. Bio-inspired adhesion control with liquids. iScience 2022, 25, 103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labonte, D.; Federle, W. Functionally different pads on the same foot allow control of attachment: Stick insects have load-sensitive ‘‘heel’’ pads for friction and shear-sensitive ‘‘toe’’ pads for adhesion. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Kovalev, A.; Eichler-Volf, A.; Steinhart, M.; Gorb, S.N. Humidity-enhanced wet adhesion on insect-inspired fibrillar adhesive pads. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, T.H.; Grohmann, C.; Bradler, S.; Gorb, S.N. Tarsal attachment pads in Phasmatodea (Hexapoda: Insecta). Zoologica 2019, 164, 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, P.D.; Büscher, T.H. Stick and Leaf-Insects of the World. Phasmids; N.A.P. Editions: Verrières-le-Buisson, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gleich, A.; Pade, C.; Petschow, U.; Pissarskoi, E. Bionik: Aktuelle Trends und Zukünftige Potenziale; University Bremen Fachbereich 4 Produktionstechnik: Bremen, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Deng, Y.; Xie, X.; Xu, L.; Xu, X.; Yuan, W.; Yang, B.; Yang, X.; Xia, X.; et al. Ultrafast Self-Gelling and Wet Adhesive Powder for Acute Hemostasis and Wound Healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2102583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Baik, S.; Kim, J.; Bok, B.G.; Song, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Pang, C. Tough carbon nanotube-implanted bioinspired three-dimensional electrical adhesive for isotropically stretchable water-repellent bioelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 32, 2107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lee, S.; Bielinski, A.R.; Meyer, K.A.; Dhyani, A.; Oritz-Oritz, A.M.; Tuteja, A.; Dasgupta, N.P. Rational design of transparent nanowire architectures with tunable geometries for preventing marine fouling. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2000672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wu, C.; Hua, M.; Wu, S.; Wu, D.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; He, X. Bioinspired multifunctional anti-icing hydrogel. Matter 2020, 2, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Becker, M.; Kovalev, A.E.; Büscher, T.H.; Gorb, S.N. Mechanical Characterization of Stick Insect Tarsal Attachment Fluid Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). Biomimetics 2026, 11, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010042

Becker M, Kovalev AE, Büscher TH, Gorb SN. Mechanical Characterization of Stick Insect Tarsal Attachment Fluid Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleBecker, Martin, Alexander E. Kovalev, Thies H. Büscher, and Stanislav N. Gorb. 2026. "Mechanical Characterization of Stick Insect Tarsal Attachment Fluid Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010042

APA StyleBecker, M., Kovalev, A. E., Büscher, T. H., & Gorb, S. N. (2026). Mechanical Characterization of Stick Insect Tarsal Attachment Fluid Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). Biomimetics, 11(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010042