Optimization of Actuator Stiffness and Actuation Timing of a Passive Ankle Exoskeleton: A Case Study Using a Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject

2.2. Experimental Data Collection

2.3. Exoskeleton Footwear in OpenSim

2.4. Musculoskeletal Modeling and Simulation in OpenSim

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Statistics

2.7. Validation of the OpenSim Exoskeleton Model

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Actuator Stiffness

3.2. Effects of Actuation Timing

3.3. Combining Effects of Actuator Stiffness and Actuation Timing

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Actuation Timing

4.2. Impact of Actuator Stiffness

4.3. Advantages of Modeling and Parametric Study

4.4. Implications and Clinical Applications

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Muscle Name |

|---|

| Adductor brevis |

| Adductor longus |

| Adductor magnus (distal) |

| Adductor magnus (ischial) |

| Adductor magnus (middle) |

| Adductor magnus (proximal) |

| Biceps femoris long head |

| Biceps femoris short head |

| Extensor digitorum longus |

| Extensor hallucis longus |

| Flexor digitorum longus |

| Flexor hallucis longus |

| Gastrocnemius lateral head |

| Gastrocnemius medial head |

| Gluteus maximus (superior) |

| Gluteus maximus (middle) |

| Gluteus maximus (inferior) |

| Gluteus medius (anterior) |

| Gluteus medius (middle) |

| Gluteus medius (posterior) |

| Gluteus minimus (anterior) |

| Gluteus minimus (middle) |

| Gluteus minimus (posterior) |

| Gracilis |

| Iliacus |

| Peroneus brevis |

| Peroneus longus |

| Piriformis |

| Psoas |

| Rectus femoris |

| Sartorius |

| Semimembranosus |

| Semitendinosus |

| Soleus |

| Tensor fascia latae |

| Tibialis anterior |

| Tibialis posterior |

| Vastus intermedius |

| Vastus lateralis |

| Vastus medialis |

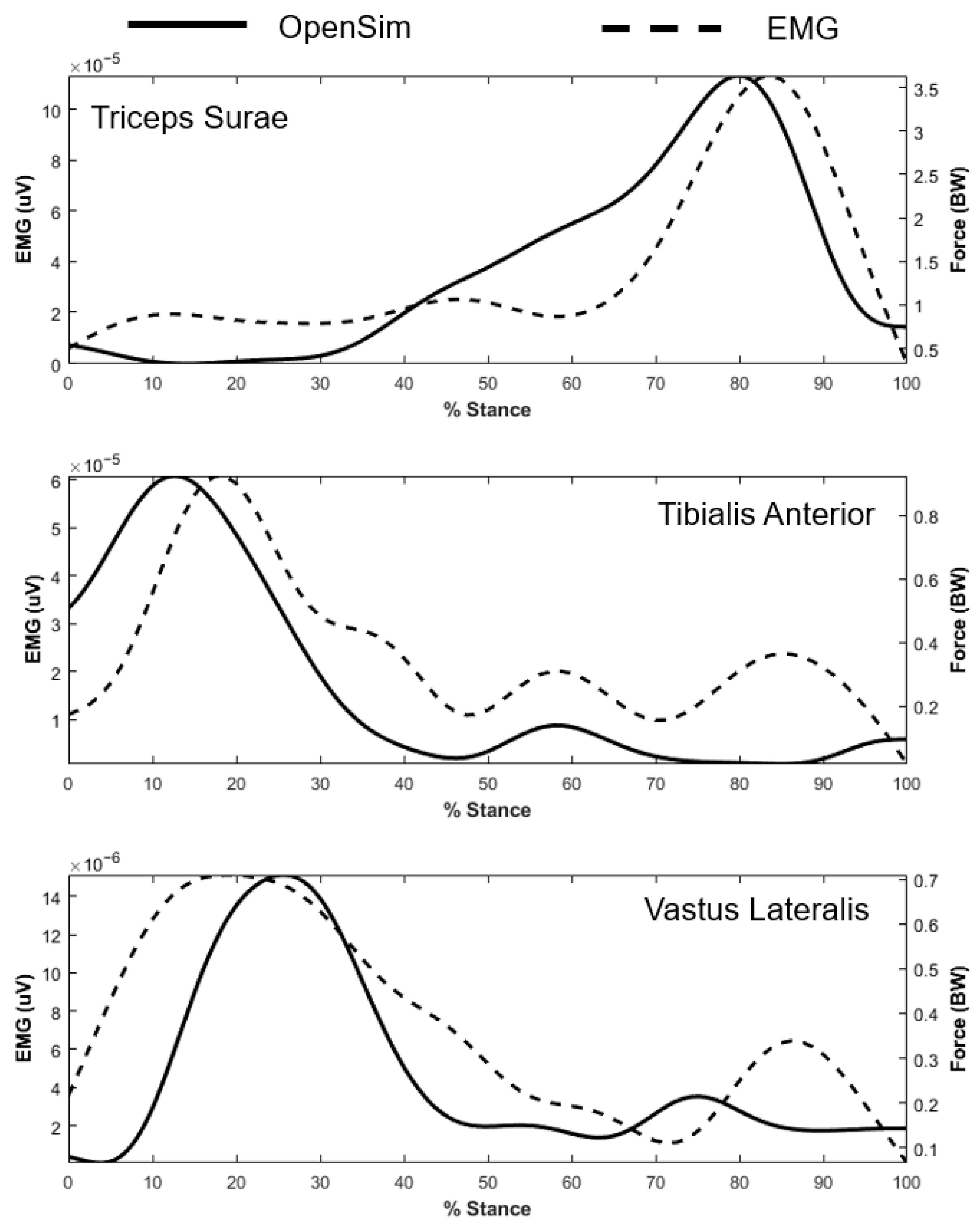

Appendix B. Validation of the OpenSim Exoskeleton Model

References

- Siviy, C.; Baker, L.M.; Quinlivan, B.T.; Porciuncula, F.; Swaminathan, K.; Awad, L.N.; Walsh, C.J. Opportunities and challenges in the development of exoskeletons for locomotor assistance. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 7, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Sumrell, R.; Goetz, L.L. Exoskeletal Assisted Rehabilitation After Spinal Cord Injury. In Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 440–447.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.P.; Grabowski, A.M. The spring stiffness profile within a passive, full-leg exoskeleton affects lower-limb joint mechanics while hopping. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 231449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougrinat, Y.; Achiche, S.; Raison, M. Design and development of a lightweight ankle exoskeleton for human walking augmentation. Mechatronics 2019, 64, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.; Hicks, J.L.; Uchida, T.K.; Habib, A.; Dembia, C.L.; Dunne, J.J.; Ong, C.F.; Demers, M.S.; Rajagopal, A.; Millard, M.; et al. OpenSim: Simulating musculoskeletal dynamics and neuromuscular control to study human and animal movement. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totah, D.; Menon, M.; Jones-Hershinow, C.; Barton, K.; Gates, D.H. The impact of ankle-foot orthosis stiffness on gait: A systematic literature review. Gait Posture 2019, 69, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrutia, W.S.; Yumiceva, A.; Thompson, M.L.; Ferris, D.P. Soft tissue can absorb surprising amounts of energy during knee exoskeleton use. J. R. Soc. Interface 2024, 21, 20240539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Acosta-Sojo, Y.; Wu, M.I.; Stirling, L. Actuation Timing Perception of a Powered Ankle Exoskeleton and Its Associated Ankle Angle Changes During Walking. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, S.; Malcolm, P.; Collins, S.H.; De Clercq, D. Reducing the metabolic cost of walking with an ankle exoskeleton: Interaction between actuation timing and power. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Quinlivan, B.T.; Deprey, L.-A.; Revi, D.A.; Eckert-Erdheim, A.; Murphy, P.; Orzel, D.; Walsh, C.J. Reducing the energy cost of walking with low assistance levels through optimized hip flexion assistance from a soft exosuit. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennard, M.; Kadone, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Suzuki, K. Passive exoskeleton with gait-based knee joint support for individuals with cerebral palsy. Sensors 2022, 22, 8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuckols, R.W.; Nuckols, R.W.; Nuckols, R.W.; Sawicki, G.S.; Sawicki, G.S. Impact of elastic ankle exoskeleton stiffness on neuromechanics and energetics of human walking across multiple speeds. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arch, E.S.; Stanhope, S.J.; Higginson, J.S. Passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis replicates soleus but not gastrocnemius muscle function during stance in gait: Insights for orthosis prescription. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2016, 40, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Bjornson, K.; Fatone, S.; Steele, K.M. Using musculoskeletal modeling to evaluate the effect of ankle foot orthosis tuning on musculotendon dynamics: A case study. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2016, 11, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, H.; Anderson, C.P.; Pipinos, I.I.; Johanning, J.M.; Casale, G.P.; Dong, J.; DeSpiegelaere, H.; Hassan, M.; Myers, S.A. Muscle forces and power are significantly reduced during walking in patients with peripheral artery disease. J. Biomech. 2022, 135, 111024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.P.; Pipinos, I.I.; Johanning, J.M.; Myers, S.A.; Rahman, H. Effects of Supervised Exercise Therapy on Muscle Function During Walking in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonabadi, A.M.; Antonellis, P.; Malcolm, P. Differences between joint-space and musculoskeletal estimations of metabolic rate time profiles. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, S.L.; Anderson, F.C.; Arnold, A.S.; Loan, P.; Habib, A.; John, C.T.; Guendelman, E.; Thelen, D.G. OpenSim: Open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 54, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.; Leutzinger, T.; Hassan, M.; Schieber, M.; Koutakis, P.; Fuglestad, M.A.; DeSpiegelaere, H.; Longo, G.M.; Malcolm, P.; Johanning, J.M.; et al. Peripheral artery disease causes consistent gait irregularities regardless of the location of leg claudication pain. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 67, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutzinger, T.J.; Koutakis, P.; Fuglestad, M.A.; Rahman, H.; Despiegelaere, H.; Hassan, M.; Schieber, M.; Johanning, J.M.; Stergiou, N.; Longo, G.M.; et al. Peripheral artery disease affects the function of the legs of claudicating patients in a diffuse manner irrespective of the segment of the arterial tree primarily involved. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, C.L.; Davis, B.L.; O’Connor, J.C. Dynamics of Human Gait; Kiboho Publishers: Cape Town, South Africa, 1999; Available online: https://search.worldcat.org/title/62596138 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Nigg, B.M.; Cole, G.K.; Nachbauer, W. Effects of arch height of the foot on angular motion of the lower extremities in running. J. Biomech. 1993, 26, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, A.; Dembia, C.L.; DeMers, M.S.; Delp, D.D.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L. Full-Body Musculoskeletal Model for Muscle-Driven Simulation of Human Gait. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 63, 2068–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Shimatani, K.; Hasegawa, M.; Murata, T.; Kurita, Y. Estimation of knee joint reaction force based on the plantar flexion resistance of an ankle-foot orthosis during gait. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.H.; Bruce Wiggin, M.; Sawicki, G.S. Reducing the energy cost of human walking using an unpowered exoskeleton. Nature 2015, 522, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.R.; Farley, C.T. Determinants of the center of mass trajectory in human walking and running. J. Exp. Biol. 1998, 201, 2935–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, T.K.; Hicks, J.L.; Dembia, C.L.; Delp, S.L. Stretching Your Energetic Budget: How Tendon Compliance Affects the Metabolic Cost of Running. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberger, B.R.; Gerritsen, K.G.M.; Martin, P.E. A model of human muscle energy expenditure. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 6, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umberger, B.R. Stance and swing phase costs in human walking. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, G.; Lee, D.; Kang, I.; Young, A.J. Effect of Assistance Timing in Knee Extensor Muscle Activation During Sit-to-Stand Using a Bilateral Robotic Knee Exoskeleton. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2021, 2021, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakmazaheri, A.; Song, S.; Vuong, B.B.; Biskner, B.; Kado, D.M.; Collins, S.H. Optimizing exoskeleton assistance to improve walking speed and energy economy for older adults. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.F.; Takahashi, K.Z. Gearing Up the Human Ankle-Foot System to Reduce Energy Cost of Fast Walking. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, G.; Ye, J.; Fu, C.; Liang, B.; Li, X. Learning to Assist Different Wearers in Multitasks: Efficient and Individualized Human-In-the-Loop Adaption Framework for Exoskeleton Robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 40, 4699–4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shushtari, M.; Foellmer, J.; Arami, A. Human–exoskeleton interaction portrait. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnúsdóttir, Í.D. Simulation of Spring Uses in an Ankle Exoskeleton During Human Gait. Kth Royal Institute of Technology. 2020. Available online: https://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1468986&dswid=8940 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Mays, R.J.; Mays, A.A.; Mizner, R.L. Efficacy of ankle-foot orthoses on walking ability in peripheral artery disease. Vasc. Med. 2019, 24, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yandell, M.B.; Tacca, J.R.; Zelik, K.E. Design of a Low Profile, Unpowered Ankle Exoskeleton That Fits Under Clothes: Overcoming Practical Barriers to Widespread Societal Adoption. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 27, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayah, R.; Sui, D.; Wade, K.A.; Chang, B.C.; Agrawal, S. Passive knee exoskeletons in functional tasks: Biomechanical effects of a SpringExo coil-spring on squats. Wearable Technol. 2021, 2, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Williams, J.; Anderson, C.P.; Mohammadzadeh Gonabadi, A.; Fallahtafti, F.; Myers, S.A.; Rahman, H. Optimization of Actuator Stiffness and Actuation Timing of a Passive Ankle Exoskeleton: A Case Study Using a Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010002

Williams J, Anderson CP, Mohammadzadeh Gonabadi A, Fallahtafti F, Myers SA, Rahman H. Optimization of Actuator Stiffness and Actuation Timing of a Passive Ankle Exoskeleton: A Case Study Using a Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliams, Jania, Cody P. Anderson, Arash Mohammadzadeh Gonabadi, Farahnaz Fallahtafti, Sara A. Myers, and Hafizur Rahman. 2026. "Optimization of Actuator Stiffness and Actuation Timing of a Passive Ankle Exoskeleton: A Case Study Using a Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010002

APA StyleWilliams, J., Anderson, C. P., Mohammadzadeh Gonabadi, A., Fallahtafti, F., Myers, S. A., & Rahman, H. (2026). Optimization of Actuator Stiffness and Actuation Timing of a Passive Ankle Exoskeleton: A Case Study Using a Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach. Biomimetics, 11(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010002