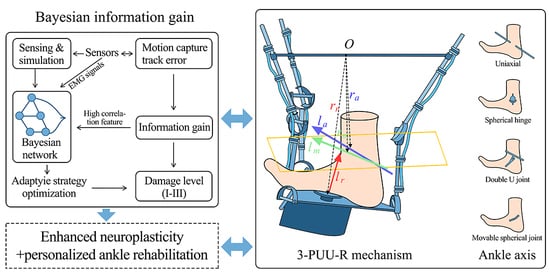

The information gain analysis, based on quantitative computation of four feature attributes—pain level, swelling diameter, joint stability, and degree of functional limitation—not only clarifies the differential contributions of each feature to disability level discrimination, with functional limitation identified as the core feature, but also reveals the underlying correlation patterns between feature attributes and the target variable (disability level). These patterns serve as key premises for constructing the Bayesian network. By establishing feature priorities and relational structures through information gain, the Bayesian network transforms the deterministic associations between features and disability levels into quantifiable probabilistic relationships, thereby constructing a reasoning framework capable of simulating the dynamic evolution from “feature attributes” to “disability classification”.

3.3.1. Bayesian Network Structure and Variable Quantification

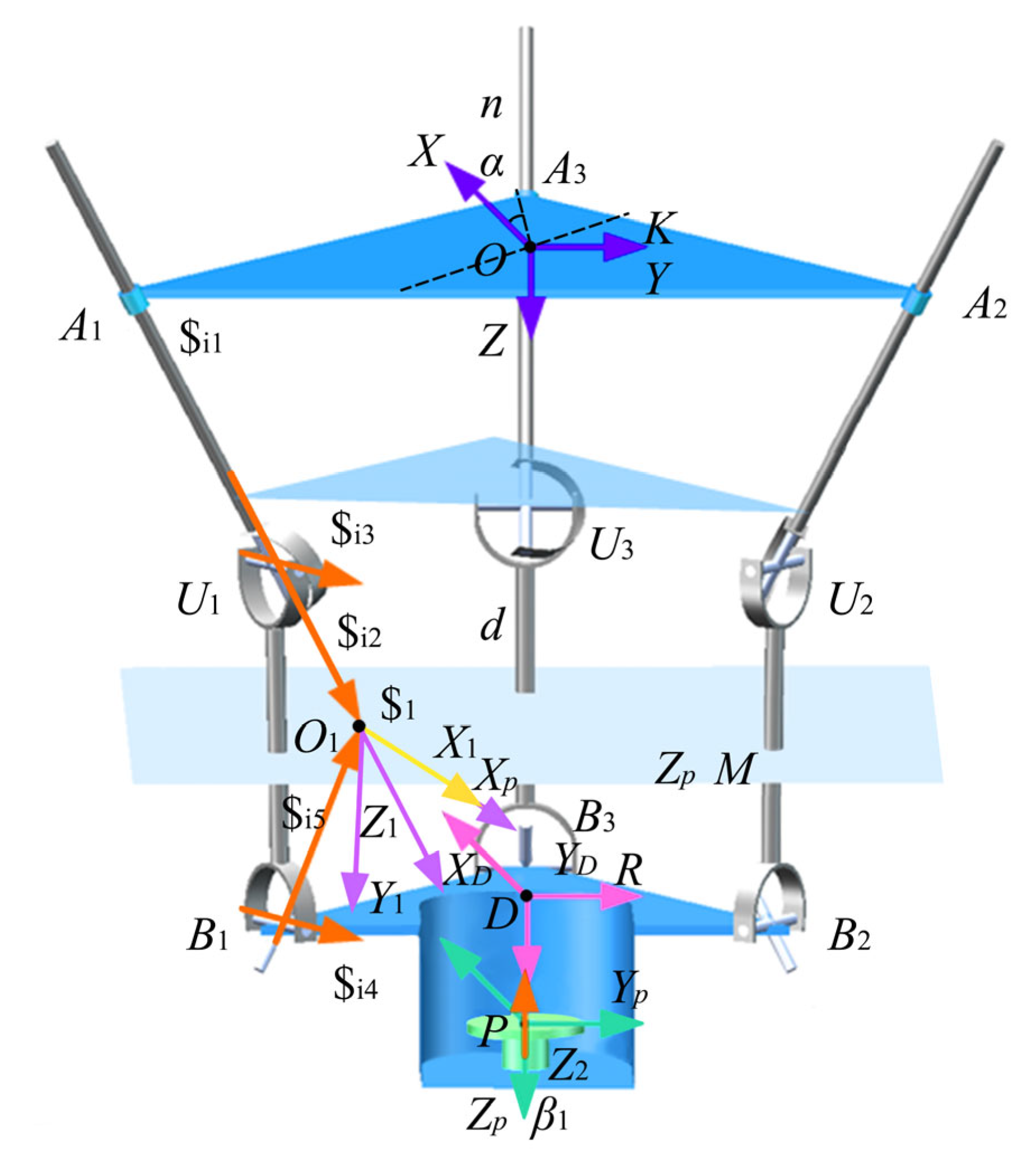

Based on the results of the information gain analysis, the degree of functional limitation was decomposed into four sub-dimensional nodes for quantification. These sub-nodes were determined through an in-depth analysis of the factors influencing the design of the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer and aligned with the fundamental theoretical framework of Bayesian networks. The node structure of the dynamic Bayesian network (DBN) was established using expert knowledge. The specific DBN node variables are as follows:

Target Node Set = {Pain Control (G1), Tissue Repair (G2), Stability Improvement (G3), Load-Bearing Function Recovery (G4) → Achieved/Not Achieved}. These target nodes represent the overall recovery status of rehabilitation training and serve as core indicators for evaluating rehabilitation effectiveness.

Second bullet; Intermediate Node Set = {Talocrural Joint Recovery Status (R1), Subtalar Joint Recovery Status (R2) → Recovered/Impaired}. These intermediate nodes reflect the recovery or damage status of the talocrural and subtalar joints during rehabilitation and are key factors influencing training outcomes.

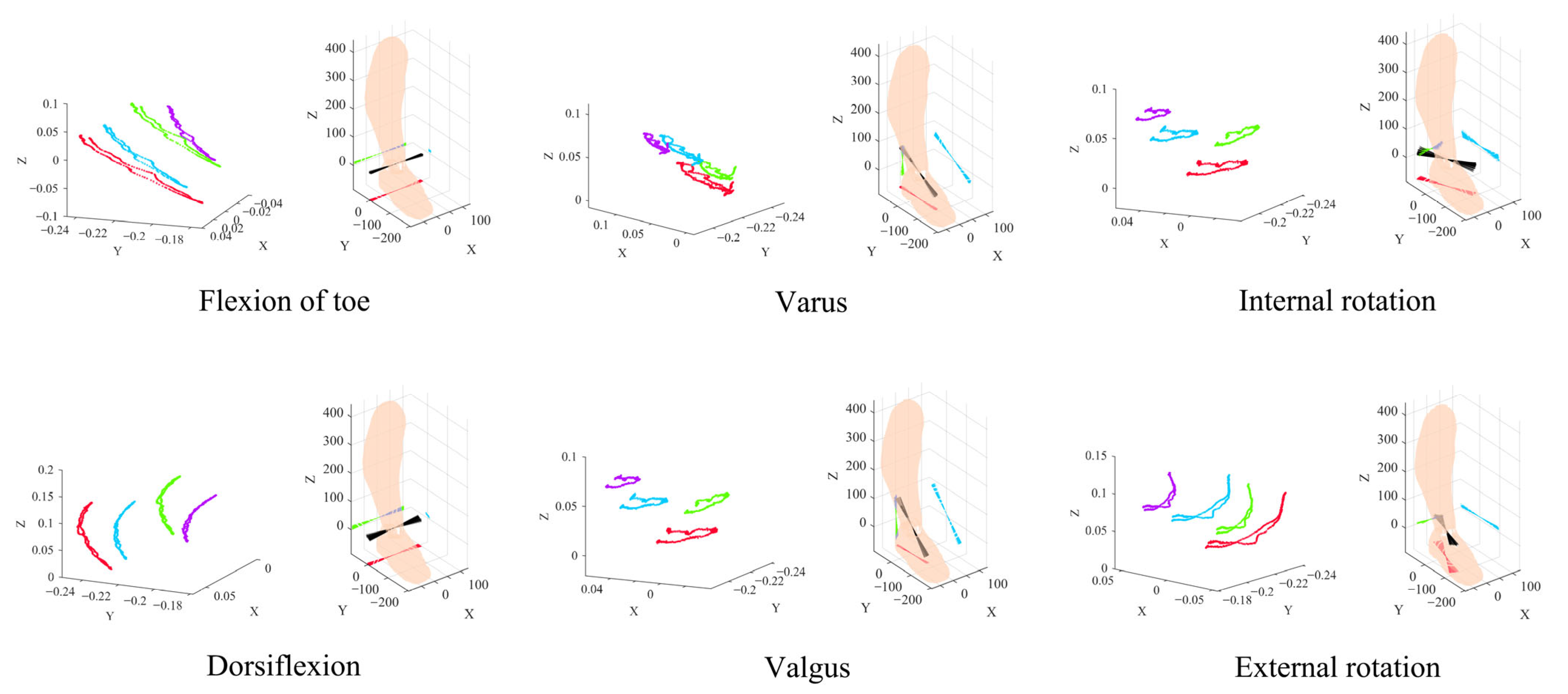

Node Set = {Flexion–Extension Function (Dorsiflexion/Plantarflexion) (B1), Inversion–Eversion Function (B2), Rotational Function (Internal/External Rotation) (B3), Stretching Function (B4) → Normal/Mildly Restricted/Severely Restricted, and Ankle Injury Level (P1) = Level I, II, III}. These observed nodes represent specific joint movements and injury levels that can be directly measured or assessed and are used to infer the states of intermediate and target nodes.

The clinical rationale for dependencies of directed edges between nodes stems from clinical patterns where more severe injuries correlate with a higher probability of restricted joint mobility—for example, the dependency “ankle joint injury grade (P1) → flexion–extension function (B1)”—and the dependency “subtalar joint repair status (R2) → stability improvement (G3)” is based on the direct impact of the subtalar joint’s structural integrity on ankle joint stability. It explains how core features selected via information gain screening—such as the degree of functional limitation (with an information gain of 0.591 bits)—determine node association priority: nodes tied to high-information-gain features (e.g., B1, B2) have higher connection weights with target nodes (G1–G4), reducing interference from redundant associations and preserving inference accuracy.

Table 3 presents the “prior probabilities of each node”, all derived from the baseline assessment results of 100 enrolled patients. Specifically, 22 patients (22%) had Grade I injury, and 53 patients (53%) did not meet pain control criteria before intervention; the prior probabilities of other nodes follow the same logic, reflecting the actual proportions of corresponding states in the sample.

Table 4 outlines the “conditional probabilities of nodes”, calculated via grouped statistics from the 100 samples. Among the 28 patients with both the tibiotalar and subtalar joints repaired, 24 achieved pain control—this proportion 24/28 ≈ 0.85 serves as the corresponding conditional probability. All other conditional probabilities are constructed using the same “sample grouping—proportion meeting criteria” logic. For readability, probabilities are rounded to two decimal places in the tables, while the exact numerators and denominators are provided in the

Supplementary Material.

Following the determination of the DBN node variables, the time slice interval was set to a single training session (30 min). The construction of Conditional Probability Tables (CPT)—a core component of the Bayesian network—adopts a hybrid approach integrating empirical clinical data, expert consensus, and simulation validation. In a Bayesian network, the distribution of node states directly affects the posterior probability inference of disability levels. Features with higher information gain are assigned greater weight, thus becoming key paths linking feature nodes to target nodes. This allows the network to more accurately infer the probability of each disability level based on feature states.

Based on this structure, the study employed the professional Bayesian network construction tool GENIE, and, incorporating both the information gain analysis and variable quantification, developed the Bayesian network structure illustrated in

Figure 2.

3.3.3. Methodological Details and Reproducibility of the Bayesian Model

To ensure model reproducibility, this section clarifies the model’s variable definitions, likelihood models, parameter learning methods, prior specifications, update equations, and core conditional probability tables—grounded in rehabilitation data from 100 ankle joint injury patients and the Bayesian network’s node structure.

All node states in the model follow a discrete multinomial distribution—i.e., for a given parent node state, the probabilities of all possible states of the child node sum to 1. The general form of the likelihood function is as follows:

Likelihood relationship between observation nodes (B1–B4) and intermediate nodes (R1–R2): P(Bj =b∣Rk =r)=θb∣r, where Bjdenotes an observation node, bits state value, Rkan intermediate node, rits state value, and θb∣rthe conditional probability parameter;

Likelihood relationship between intermediate nodes (R1–R2) and target nodes (G1–G4): P(Gm =g∣R1 =r1,R2 =r2 )=θg∣r1 ,r2, where Gmdenotes a target node, gits state value, and θg∣r1 ,r2 the conditional probability parameter.

The proposed model propagates uncertainty analytically through the Bayesian network structure. All node states are modeled as multinomial variables, and their parameters are learned from data under conjugate Beta/Dirichlet priors. Given observed evidence, posterior distributions over intermediate and target nodes are obtained by applying standard Bayesian update rules and exact inference in the directed acyclic graph. In this study, closed-form updates are sufficient to capture uncertainty in the multinomial parameters and to compute posterior probabilities and credible intervals, without resorting to explicit Monte Carlo sampling. Sampling-based techniques such as Markov chain Monte Carlo or particle filters could be incorporated in future work for more complex network structures or continuous EMG features.

All model parameters (prior probabilities, conditional probabilities) are learned via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), using baseline assessment data and post-training follow-up data from 100 patients:

Prior probability learning (corresponding to

Table 4): For root nodes without parent nodes (P1, B1–B4), their prior probability P(X = x) equals the frequency of node Xtaking state x in the sample, as shown in Equation (4):

Conditional probability learning (corresponding to

Table 5): For child nodes with parent nodes (R1–R2, G1–G4), their conditional probability P(Y=y∣Parent(Y)=p) equals the frequency of child node Ytaking state y among samples where parent node(s) Ytake state p—i.e., P(Y = y \mid \text{Parent}(Y) = p) = \frac{\text{Number of cases with child node } Y = y \text{ among samples where parent node(s) } Y = p}{\text{Total number of cases where parent node(s) } Y = p}}.

The overall network structure is primarily determined by clinical expert knowledge about causal relations between injury level, functional limitation, joint repair and rehabilitation goals, and is further constrained by the feature ranking results of Bayesian information gain. This “expert-informed plus IG-filtered” design limits the search space and reduces the risk of overfitting that can occur in fully data-driven structure learning. To check generalization, the dataset is split into training and validation subsets; CPTs are learned on the training set and predictive performance for disability level and goal attainment is evaluated on the validation set, confirming that the learned probabilities are stable and not overly sensitive to small perturbations of the data.

Posterior probability updates follow a hierarchical logic of observation nodes → intermediate nodes → target nodes, with core equations presented below:

Observation nodes (B1–B4) have no parent nodes; their posterior probabilities are corrected based on the frequency of real-time training data, as shown in Equation (5):

Taking intermediate node R1 as an example (its parent nodes are B1–B4), its posterior probability is calculated using Bayes’ theorem and the law of total probability, as shown in Equation (6):

where P(R1 = r) is the prior probability of R1 (

Table 4);

is the joint likelihood of the observation nodes (B1–B4 are conditionally independent given R1, so it decomposes into

; the denominator is a normalization constant computed by

. The posterior update equation for R2 follows the same logic as R1.

Taking target node G4 as an example (its parent nodes are R1 and R2), the posterior probability calculation Equation (7) is:

where P(G4 = g) is the prior probability of G4 (

Table 4); P(R1=r1 ,R2=r2 ∣G4=g) is the joint likelihood of the intermediate nodes (parameters from

Table 5); the denominator is a normalization constant computed by summing over g = 0.1:

. The posterior update equations for G1–G3 follow the same logic as G4.

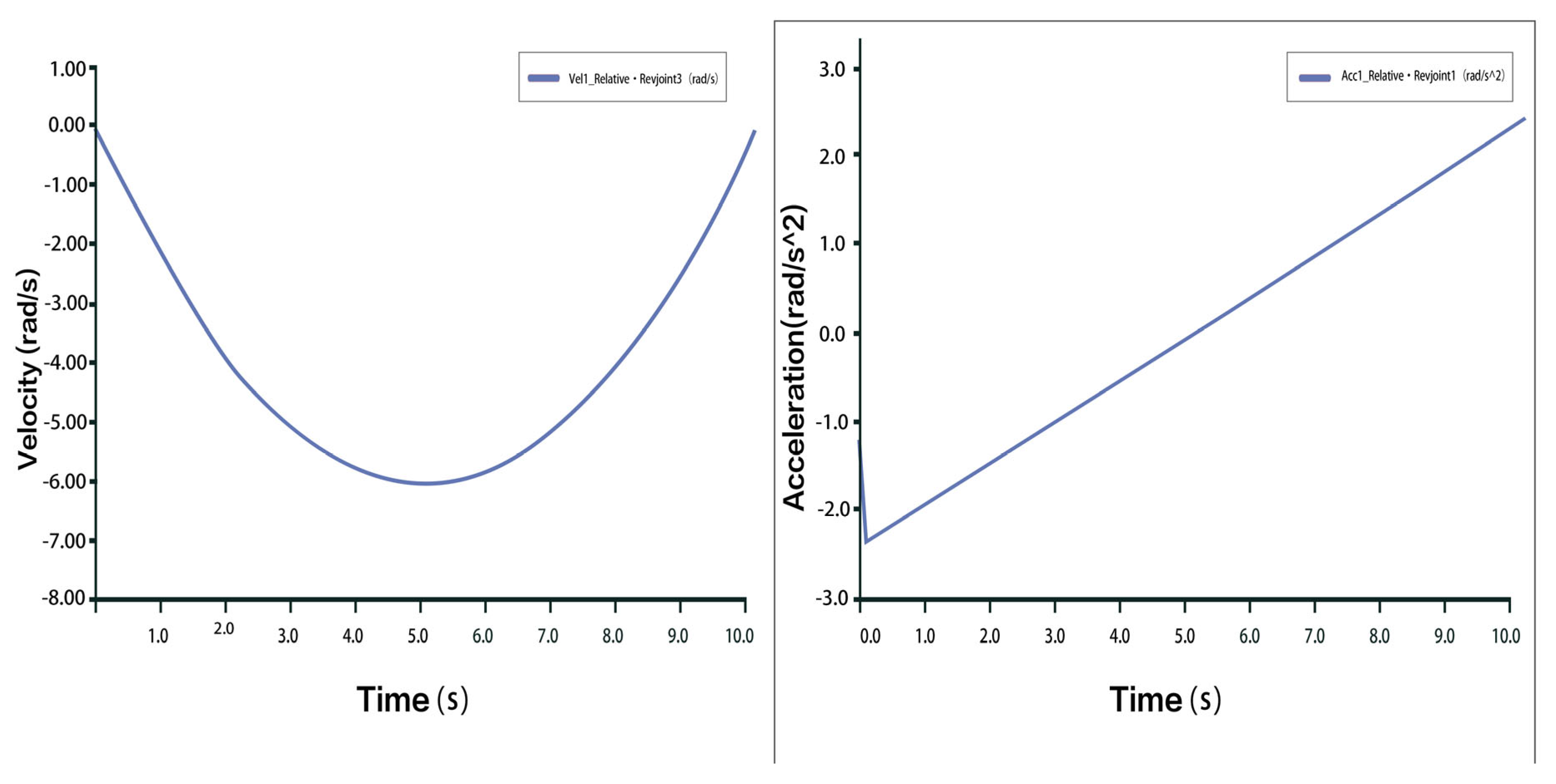

3.3.4. Node Status Scoring Criteria

To precisely evaluate the intervention effectiveness of the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer, this study conducted a six-week follow-up investigation involving 100 patients with ankle injuries. Multidimensional data collection was employed to ensure comprehensive and accurate information acquisition. During the data collection phase, observational methods were used to record the training conditions while patients used the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer. This included measurements of load intensity, activity frequency, real-time posture (e.g., flexion and inversion angles captured via motion capture systems), training duration, rest intervals, and immediate patient responses (such as pain feedback and degree of functional limitation). These observations were used to construct a behavioral database for ankle function training. In parallel, a questionnaire survey was designed based on the observed data, covering patient-reported experiences such as perceived force during training, self-assessed training difficulty, device-wearing comfort, and subjective evaluations of functional improvement. These supplemented the objective data by quantifying the user experience. Additionally, professional functional assessments were performed using joint range-of-motion measurement devices and EMG monitoring technologies. These tools collected precise data on ankle flexion–extension, inversion–eversion, rotation, and stretching functions, which were evaluated against clinical diagnostic criteria to assess joint recovery; see

Supplementary Material.

For parameter optimization and outcome evaluation of the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer, a multidimensional quantification framework based on information gain analysis was developed using the GeNIe modeling environment (BayesFusion). The disability level (P1), identified as the core decision variable through information gain screening, was assigned the highest weight. Level III injuries (score: 5) directly determined the initial intervention plan and device calibration benchmark, triggering high-intensity intervention modes in the trainer. At the functional recovery node level, flexion (B1) and inversion (B2) were designated as core training targets (score: 5), addressed through dynamic angle correction modules for precision intervention. Rotation (B3) and stretching (B4) functions (score: 4) served as auxiliary recovery targets, to be gradually improved through progressive training, and were scored lower than the core functions. In terms of joint repair assessment, the talocrural joint (R1)—as the key load-bearing structure—was scored 5 when impaired and served as a critical index for adjusting load-bearing parameters of the trainer, directly reflecting its therapeutic effect. The subtalar joint (R2), responsible for supplementary stability, was assigned a score of 4 and adjusted via a lateral support module. In the rehabilitation goal system, load-bearing function recovery (G1, score: 5) was identified as the ultimate intervention target for the trainer, requiring full-cycle training from passive assistance to active load-bearing, directly reflecting the device’s value. Stability enhancement (G2, score: 4) was the necessary prerequisite, achieved through a balance control module. Pain control (G3, score: 3) and tissue repair (G4, score: 3) provided foundational support through biofeedback and analgesic modes. This scoring framework, with its hierarchical weighting and modular response mechanism, enables the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer to adaptively achieve foundational support via pain management and biofeedback, while prioritizing higher-order functional restoration goals; details are provided in

Table 5.

In the quantitative evaluation system of the ankle rehabilitation trainer, unachieved states (e.g., G1 = 1, G2 = 1) are not assigned scores. This design stems from the framework’s focused orientation toward the positive intervention goals of the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer. The core logic behind this approach can be explained through the following three aspects:

The scoring system quantifies only the “achieved states,” assigning different weights (3–5 points) to each target node (e.g., G1–G4) to directly reflect their contribution to overall rehabilitation outcomes. For example, load-bearing function recovery is assigned the highest score, emphasizing its role as the ultimate goal. The unachieved state essentially represents a “deficiency requiring improvement.” Its function lies in offering a contrast for verifying the trainer’s intervention effect (e.g., a decrease in unachieved rate indicates effective device regulation), rather than conveying value through positive scoring.

Within the Bayesian network framework, the probabilities of unachieved states (e.g., the posterior probability of G1 = 1) are dynamically computed based on prior data and conditional probability tables. Their analytical value lies in probability trends rather than absolute scores. For instance, if the probability of G1 = 1 drops from 52% to 37% after intervention, this change quantitatively reflects the improvement in pain control and sufficiently supports the evaluation of the device’s effectiveness without requiring additional scoring.

The core function of the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer is to facilitate the transition from “unachieved” to “achieved.” The scoring system, therefore, only needs to clarify which achieved states take priority (e.g., stability enhancement should be prioritized). The intervention priority of unachieved states is already implicitly represented by the corresponding weights of the achieved states (e.g., a score of 4 for G3 = 0 implies that intervention toward achieving G3 = 1 is a priority), thus avoiding redundant information that might interfere with decision-making in device regulation.

In summary, the exclusion of scores for unachieved states ensures that the quantitative framework remains focused on the positive intervention objectives of the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer. It also aligns with the Bayesian network’s core logic—favoring probabilistic inference over additive scoring—thereby enhancing the efficiency and precision of priority judgments in device modulation. The prior probability distributions of each node are shown in

Table 3. The Posterior probability of each node are shown in

Table 6. Compared with existing EMG signal-based methods, the BIG framework systematically optimizes the decision-making process and significantly enhances personalized rehabilitation outcomes.

Through multidimensional validation of prior, conditional, and posterior probabilities within a Bayesian framework, this study systematically demonstrates both the clinical value and theoretical soundness of the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer design, as shown in

Figure 3. The main conclusions are as follows:

The intervention of the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer significantly enhanced the achievement rates of core rehabilitation goals (G1–G4) and joint structural repair outcomes. For core objectives, pain control (G1) demonstrated a marked improvement from 38.0% to 62.9%, while tissue repair (G2) rose from 42.0% to 67.6%. Notably, load-bearing function recovery (G4) saw a dramatic surge from 20.0% to 65.8%. Concurrently, recovery rates for key joint structural nodes improved substantially: the talocrural joint (R1) progressed from 31.0% to 58.4%, and the subtalar joint (R2) increased from 31.0% to 57.7%. These findings highlight the trainer’s efficacy in driving measurable advancements across both functional and structural rehabilitation domains.

Conditional probability analysis validated the clinical efficacy of the causal path-way “joint structural repair → functional recovery,” demonstrating that when both the talocrural joint (R1) and subtalar joint (R2) achieved recovered states (R1 = 0, R2 = 0), the achievement rates for all functional goals reached their peaks: 85.0% for pain control (G1), 92.0% for tissue repair (G2), 90.0% for gait stability (G3), and 95.0% for load-bearing function recovery (G4). These results were highly consistent with posterior intervention trends, where improvements in R1/R2 recovery rates correlated directly with synchronous enhancements in G1–G4 outcomes. This alignment not only confirms the design rationale of structural repair through mechanical correction modules but also underscores its profound compatibility with the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ankle rehabilitation. The findings thereby establish a robust theoretical framework for the intervention mechanism, reinforcing the clinical relevance of targeted joint repair in driving functional recovery.

For Grade III injuries (P1 = 2), the stepwise training protocol demonstrated clear efficacy. Posterior data show that the proportion of Grade III patients dropped to 20.0% from a high baseline, and their load-bearing function recovery (G4) achievement rate increased from 20.0% to 65.8%. These results confirm that the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer enables precise intervention for complex injuries through dynamic adjustment of training intensity and mechanical support parameters. This strongly supports the clinical applicability of the device’s “personalized intervention” design concept and confirms its capacity to accommodate the full spectrum of injury severity—from mild to severe.

In summary, this study, through a multidimensional probabilistic framework, systematically verifies the intelligent ankle rehabilitation trainer’s advantages in effectiveness, scientific rationality, and clinical adaptability. Using Bayesian information gain, we identified the core features that contribute most to discriminating ankle injury severity, which serve as key input variables for constructing the Bayesian network—thereby reducing interference from redundant features and improving the accuracy of injury-grade inference. At the same time, high-association features determined by information gain can directly inform the prioritization of functional capabilities in the mechanical design of the rehabilitation device, ensuring the design concentrates on ameliorating the principal injury-related functional impairments. Unlike standard Bayesian inference, which is limited to state estimation, the Bayesian Information Gain (BIG) framework introduces information gain as an optimization criterion. It reduces classification uncertainty via feature selection and drives dynamic adjustment of training strategies. This proactive optimization mechanism addresses the passivity of traditional probabilistic inference, significantly enhancing both the efficiency and accuracy of rehabilitation decision-making, and paves the way for advancing intelligent rehabilitation technologies toward precision-driven, full-cycle management.